In 1943, although the end of the last war was still two years away, the thoughts of the London County Council were focussed on the post war reconstruction of the city.

London had yet to suffer the barrage of V1 and V2 weapons, but in 1943 the London County Council published the County of London Plan, a far reaching set of proposals for the post-war development of the city.

I find the many plans for London that have been published fascinating to read. They show the challenges of trying to forecast the needs of a city such as London for decades to come. They provide a snapshot of the city at the time, and they demonstrate that time after time, development of London has reverted to ad-hoc rather than grandiose, city wide schemes.

In the forward to the plan, Lord Latham the Leader of the London County Council wrote:

“This is a plan for London. A plan for one of the greatest cities the world has ever known; for the capital of an Empire; for the meeting place of a Commonwealth of Nations. Those who study the Plan may be critical, but they cannot be indifferent.

Our London has much that is lovely and gracious. I do not know that any city can rival its parks and gardens, its squares and terraces. but year by year as the nineteenth and twentieth centuries grew more and more absorbed in first gaining and then holding material prosperity, these spaces were over-laid, and a tide of mean, ugly, unplanned building rose in every London borough and flooded outward over the fields of Middlesex, Surrey, Essex, Kent.

Athens was the glory of Greece, Rome the great capital of a great Empire, a magnet to all travellers. Paris holds the hearts of civilised people all over the world. Russia is passionately proud of Moscow and Leningrad; but the name we have for London is the Great Wen.

It need not be so. Had our seventeenth century forefathers had the faith to follow Wren, not just the history of London, but perhaps the history of the world might have been different.

Faith, however was wanting. It must not be wanting again – no more in our civic, than in our national life. We can have the London we want; the London that people will come from the four corners of the world to see; if only we determine that we will have it; and that no weakness or indifference shall prevent it.”

The 1943 plan provides plenty of detailed analysis of London at the time, with some graphical presentation using techniques I have not seen in any earlier London planning documents.

The following diagram from the report provides a Social and Functional Analysis of London. This divides London into individual communities, identifies the main functions of the central areas, shows town halls, man shopping centres and open spaces.

The City is surrounded by an area of “Mixed General Business and Industry”. Press (Fleet Street) and Law (the Royal Courts of Justice) provide the main interface between the City and the West End, which also contains the University and Government areas of the city.

The darker brown communities are those with a higher proportion of obsolescent properties. (click on any of the following maps to enlarge)

The plan placed considerable importance on community structure within London:

“The social group structure of London is of the utmost importance in the life of the capital. Community grouping helps in no small measure towards the inculcation of local pride, it facilitates control and organisation, and is the means of resolving what would otherwise be interminable aggregations of housing. London is too big to be regarded as a single unit. If approached in this way its problems appear overwhelming and almost insoluble.

The proposal is to emphasise the identity of the existing communities, to increase their degree of segregation, and where necessary to reorganise them as separate and definite entities. The aim would be to provide each community with its own schools, public buildings, shops, open spaces etc. At the same time care would be taken to ensure segregation of the communities was not taken far enough to endanger the sense of interdependence on the adjoining communities or on London as a whole.”

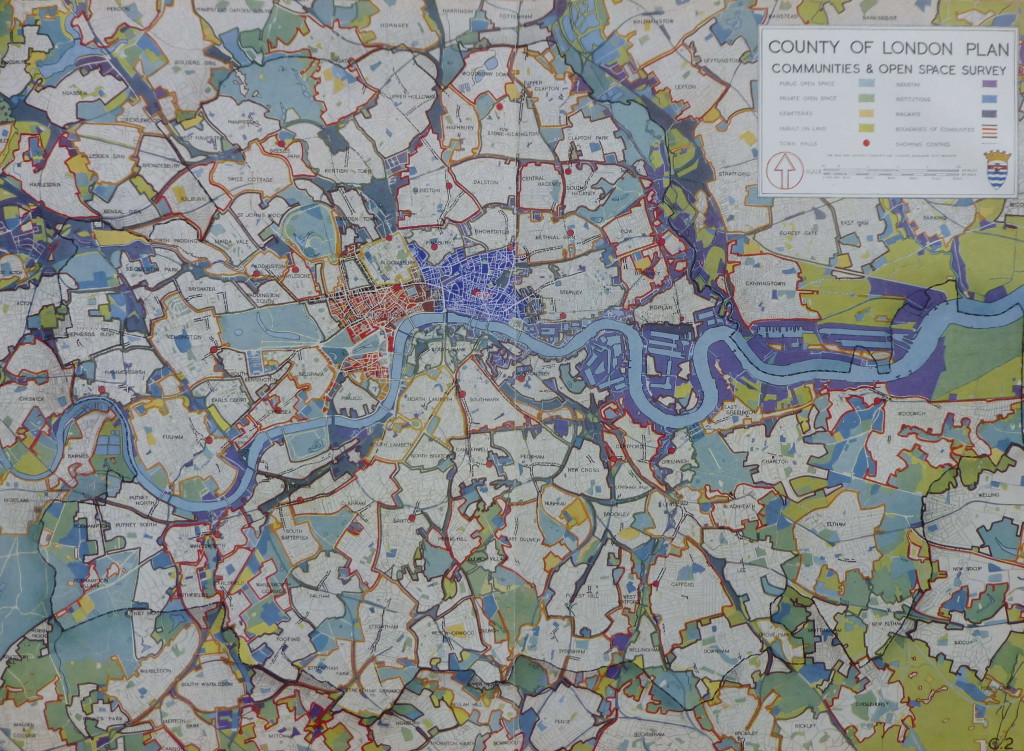

The following map shows a more traditional view of the Communities and Open Spaces within the Greater London area.

The plan identifies a number of issues that divide communities, chief among them the way that railways, mainly on the south of the river have divided local communities with railway viaducts acting as a wall between parts of the same community.

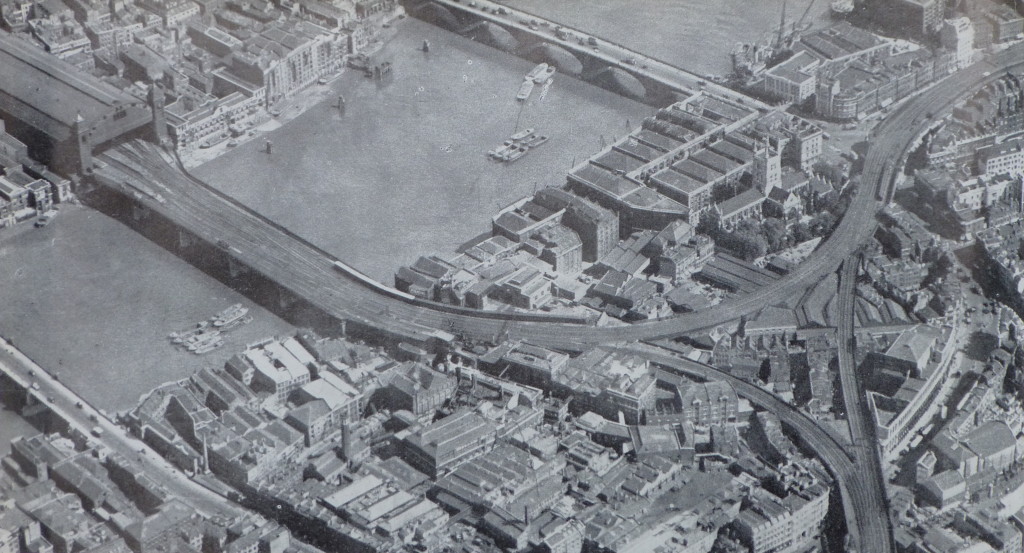

The plan used the following photo of the railway viaducts on the approach to Cannon Street Station and down to Waterloo to illustrate the impact. The report, as with a number of other proposals for the post war development of London, placed considerable importance on moving the over ground railways into tunnels to remove viaducts, bring communities together and to remove rail bridges, such as the one shown leading into Cannon Street Station, from across the Thames.

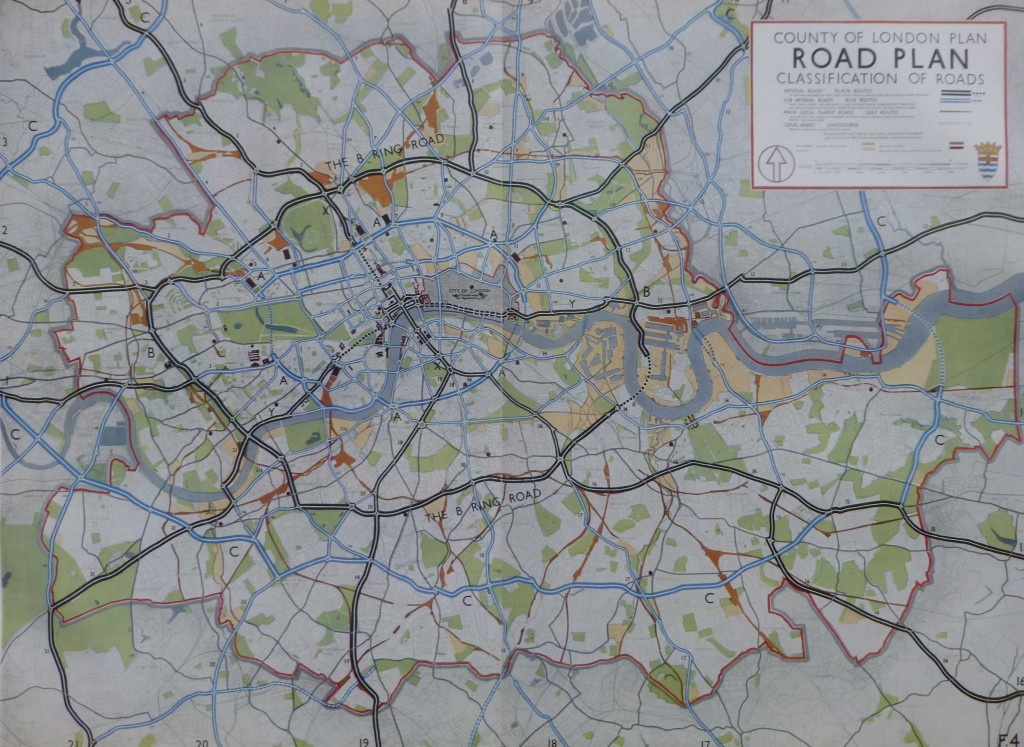

The first sentence in the section on Roads is remarkable, remember this was written in 1943, not 2015:

“The need for improved traffic facilities in and around London has become so acute, that unless drastic measures are taken to relieve a large number of the thoroughfares, crossings and junctions of their present congestion, there will be a grave danger that the whole traffic system, will, before long, be slowed to an intolerable degree.”

The plan also emphasises the dangers resulting from traffic on London roads with in 1937 a total of 57,718 accidents in the Greater London area that involved personal injury.

At the time of planning, the ratio of cars to population was one to twenty two. The plan expects a considerable increase in car usage after the war, stating that the war has “made a vast number of people for the first time mechanically minded, and has given a great impetus to the production of motor vehicles.”

Parking this number of cars was also expected to be a problem. The plan includes the provision of underground car parks and that legislation should be passed that enforces the provision of car parking facilities for all buildings of a certain size.

A new ring road was planned for fast moving traffic. This is shown as the B Ring Road in the following map. Circling the central area of London and with a tunnel under the Thames running from the Isle of Dogs to Deptford. Roads radiating out from the B Ring Road would allow traffic circulating around London to quickly leave to, or arrive from the rest of the country.

The plan also identifies the “cumulative effect of street furniture on the appearance of London and on the convenience of pedestrians and vehicular traffic is very considerable” and recommends the formation of a Panel to provide a degree of control over street furniture, with a preference for embellishing streets with tree-planting and green-swards. With the level of street furniture on the streets today, perhaps a Panel to control this would have been a good outcome.

The provision of more open space was seen as a key component of the future development of London with the standardised provision of space for Londoners.

At the time the plan was written there was a considerable variation in the amount of open space available to Londoners in different boroughs, for example the inhabitants of Woolwich benefited from the availability of 6 acres per 1,000 inhabitants, whilst for those of Shoreditch the amount of open space available was 0.1 acres per 1,000 inhabitants.

The provision of 4 acres of open space for every 1,000 inhabitants across London was adopted as a key strategy for future development.

Examples of how open space could be made available to the public included the use of Holland Park, the grounds of the Hurlingham Club and the Bishops Palace Grounds in Fulham.

Indeed at Hurlingham, after the war, the London County Council made a compulsory purchase of the polo grounds to build the Hurlingham Park recreation grounds, along with the Sullivan Court flats and a school, leaving the Hurlingham Club with the 42 acres retained today.

The plan also states that “The difficulty of finding alternative housing accommodation for people displaced when open spaces are provided in built up areas, has been partly removed through the destruction of many houses by bombing.” I am not sure what the view of those who had lost their homes through bombing would have been, that there was a plan to replace their homes with open space.

The following Open Space Plan shows the proposed new public open space in dark green:

The 1943 plan presents a fascinating view of the industrialisation of London.

The East End of London and the London Docks were well known industrial areas, however every London borough had a significant amount of factories and industrial employment. The report includes a summary of industry for every London borough. I have shown a sample below to indicate the range of factory numbers, employment levels and types of industry across some of the London boroughs.

| Borough | Principal industries according to numbers employed | Size of Factories | Factory numbers in 1938 | Factory employees in 1938 |

| Bermondsey | Food, engineering, and chemicals, including tanneries | Each of the principal industries has a large number of factories | 711 | 31,058 |

| Bethnal Green | Furniture and clothing | Furniture factories very small, clothing small with a few large premises | 1,746 | 15,945 |

| Finsbury | Clothing, printing and engineering, though appreciable numbers are employed in all other industries | Mostly medium to small, though each industry has a number of large factories and the average size if bigger than in Bethnal Green, Shoreditch or Stepney | 2,523 | 66,556 |

| Islington | Engineering, clothing, furniture and miscellaneous (principally builders’ yards, cardboard boxes and laundries) | Mostly small, though engineering, furniture and miscellaneous each has a number of medium sized factories | 1,998 | 35,649 |

| Stepney | Clothing, food (including breweries and tobacco) and engineering | Mostly small (especially clothing) but each industry has a number of large factories | 3,270 | 58,073 |

| Westminster | Clothing, printing and engineering, though appreciable numbers are employed in all other industries | Mostly small (especially clothing), but each industry has several large factories | 4,414 | 46,528 |

The plan identifies a trend of decentralisation which had already being happening for a number of decades with the gradual migration of industry from central to outer London and also identifies the improvement in transport facilities as enabling industry to move away from the main residential areas.

Even in 1943 the report identifies the importance of the new industrial estates at Slough, Park Royal, along the Great West Road etc. as the future home for more of London’s industry.

What the plan does not identify is how the Docks would change over the coming decades. The expectation was that the London Docks would continue to provide a key role in both London and the Nation’s global trade.

The following map shows the proposed approach for how industry would be located across the Greater London area. Note the concentration of industrial areas around the Docks and along the Thames.

In addition to planning at the Greater London level, the 1943 report also focussed on a number of specific areas that had suffered extensive bomb damage and were therefore important redevelopment locations.

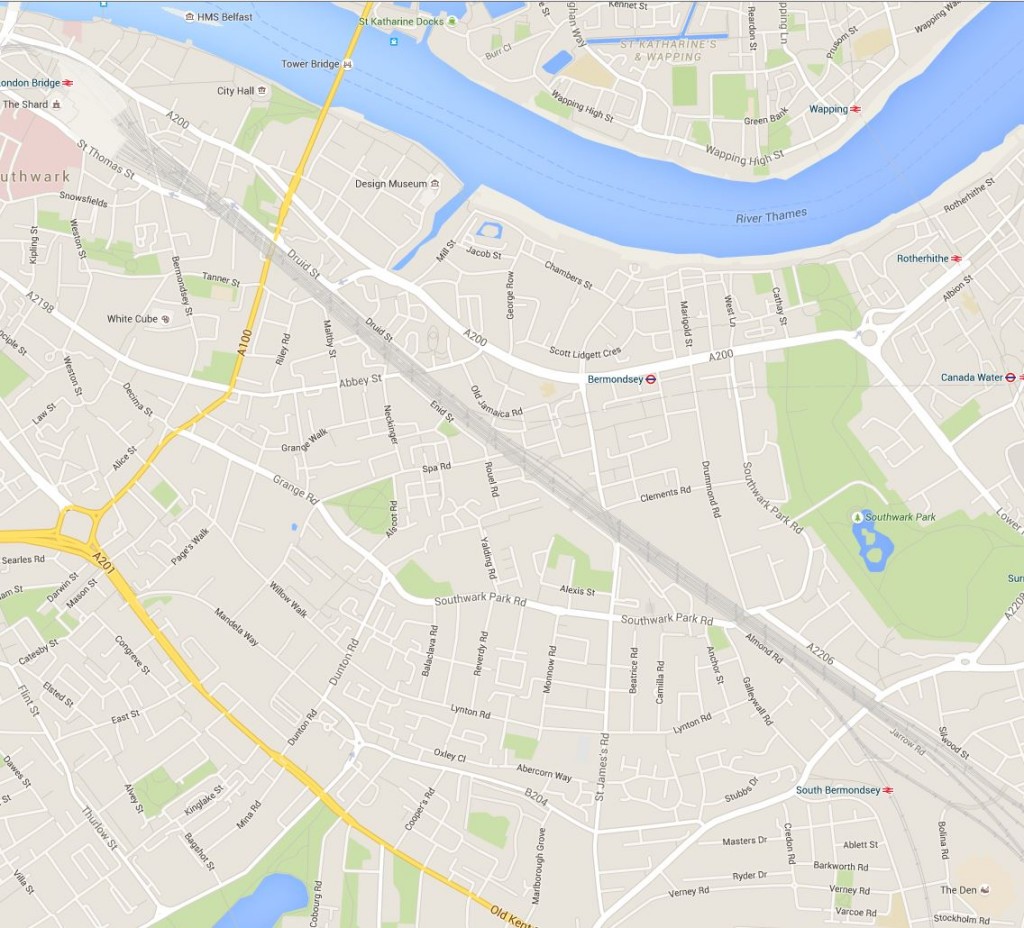

An example is the redevelopment of Bermondsey. The following plan shows the proposed post-war reconstruction of Bermondsey:

The plan for Bermondsey illustrates how the 1943 plan proposed:

- replacing the long runs of railway viaducts with underground rail tunnels thereby avoiding the way the viaducts divided communities

- a considerable increase in the amount of public open space

- wide through roads to carry traffic efficiently across London

- reduced housing density

How far these plans were actually implemented after the war can be judged by comparison with the following 2015 map of Bermondsey. The railway viaducts still remain, cutting across the borough, and the street layout remains largely unchanged. Southward Park provides a large amount of open space, however there is not the amount proposed in 1943 and the large park planned to run adjacent to the Old Kent Road was not constructed.

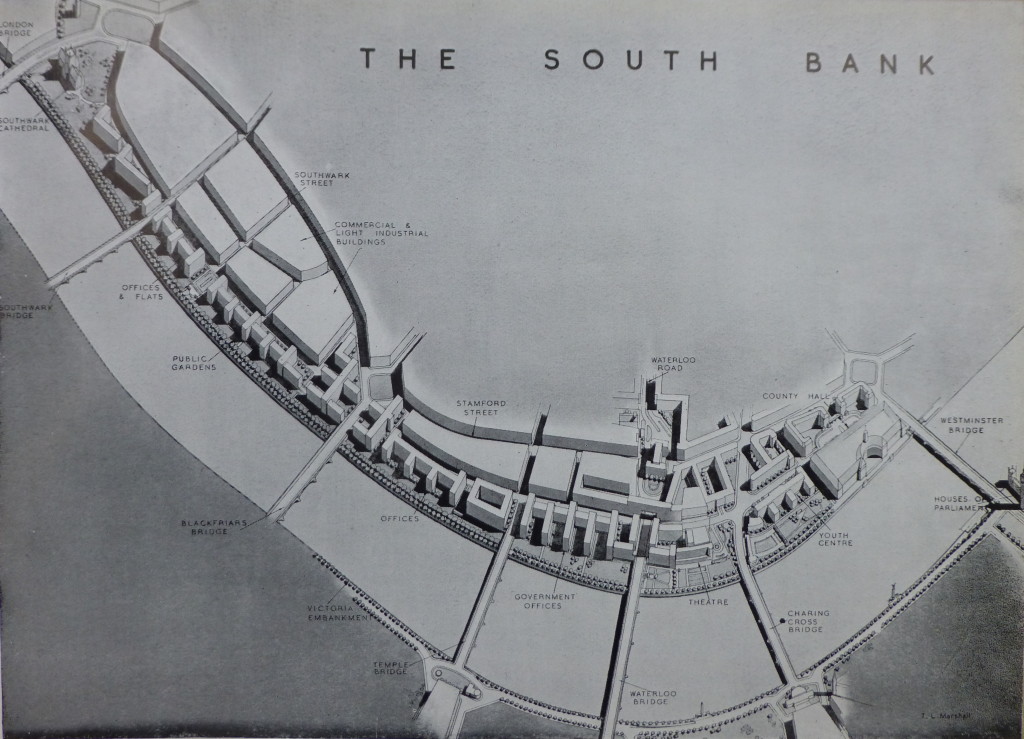

Another focus for significant redevelopment was the South Bank. Starting from Westminster Bridge and County Hall at the right of the following picture, the plans consisted of:

- a Youth centre to the left of County Hall

- a new road bridge across the Thames leading to Charing Cross to replace the rail bridge after the railways had been diverted underground

- a Theatre between Charing Cross and Waterloo Bridges (which did get built in the form of the Royal Festival Hall)

- Government offices running to…..

- a new bridge – Temple Bridge – across the Thames from the South Bank to Temple Station, in exactly the same place as the proposed Garden Bridge

- offices then running to Blackfriars Bridge

- followed by office and flats leading up to a landscaped area around Southwark Cathedral

- with public gardens running the length of the Thames embankment

When reading the plan I was really surprised to find that in 1943 there were proposals for a bridge across the river at Temple. Although this would have been more functional than the proposed Garden Bridge, it would still have blocked some of the view from Waterloo Bridge and the South Bank across to St. Paul’s and the City.

The following picture is an artist impression from the 1943 report of the proposed new Charing Cross road bridge:

The 1943 report places considerable importance on the need for housing after the war, claiming that “Of the many aspects of London’s future in so far as replanning is concerned, that of housing must claim first attention.” and that “The provision of new housing accommodation will be a most urgent task to be tackled immediately after the war.” Some things do not change, although in 1943 the plans for housing in central London were very much the provision of affordable housing for Londoners rather than the endless development of luxury apartments we see today.

The 1943 plan proposes a comprehensive housing plan to address the need to improve the housing conditions for Londoners as well as providing the number needed.

The following photo from the 1943 plan shows some of the building commenced prior to the war. This is the White City Housing Estate, Hammersmith. Construction started in 1936 and was suspended in 1939. The plan states that when work recommences, the estate will cover an area of 52 acres and comprise 49, 5 storey blocks with accommodation for 11,000 people.

The White City Stadium can be seen on the left of the photo. Completed in 1908 for the Summer Olympics of the same year, the stadium was demolished in 1985 following which the BBC occupied the site. The BBC are now gradually vacating the site so it will be interesting to see what happens with this significant site in the future. (There is plaque on one of the BBC White City buildings at the point of the finishing line of the 1908 track)

The 1943 plan recommends the development of housing estates and uses the Roehampton Cottage Estate in Wandsworth as an example of the type of estate that should be built, including the preservation of trees which “adds greatly to the attractive lay-out”

The 1943 plan also makes recommendations for greater architectural control and uses the following view of Oxford Street as an example of “the chaos of individual and uncoordinated street development”

The 1943 plan also makes recommendations for greater architectural control and uses the following view of Oxford Street as an example of “the chaos of individual and uncoordinated street development”

The plan recommends “that Panels of architects and planners might be set up to assist the planning authority in the application of a control for street design, similar to those already in operation in other countries, notably in America and Scandinavia. Cornice and first floor levels, as well as the facing materials used, should be more strictly controlled so as to give a sense of continuity and orderliness to the street”.

The 1943 plan is a fascinating read, not only covering London at the time, but also how London could be today if these plans had of been adopted in full. I have only been able to scratch the surface of the report in this week’s post.

Reading the plan it is clear that some issues do not change, for example housing and traffic congestion.

The plan also highlights the difficulty in planning for the future. There is only a very limited reference to “Aerodromes”, beginning with “All the portents indicate that, after the war, there will be a very considerable expansion in air transport for passengers and, perhaps, for freight. Any plan for the future of London must have close regard for these eventualities.”

The plan does seem to rule out the construction of a large airport within the central London area as this would be “inimical to the interests and comfort of large sections of the population to embark on a scheme of this kind” The post war development of Heathrow was not considered in 1943.

In many ways I am pleased that many of the plans for the large scale redevelopment proposed in the 1943 plan did not take place. As with Wren’s plans for the City after the Great Fire, London tends to avoid large scale planning and seems to evolve in a haphazard manner which contributes much to the attraction of the city, although I feel that this is now under threat with the rows of identical towers that seem to be London’s future.