Following last week’s post on London Fields, for this week’s post I am again in search of another of my father’s 1980s photos, also in Hackney, but this one, judging by other photos on the same strip of negatives, seems to be from 1986.

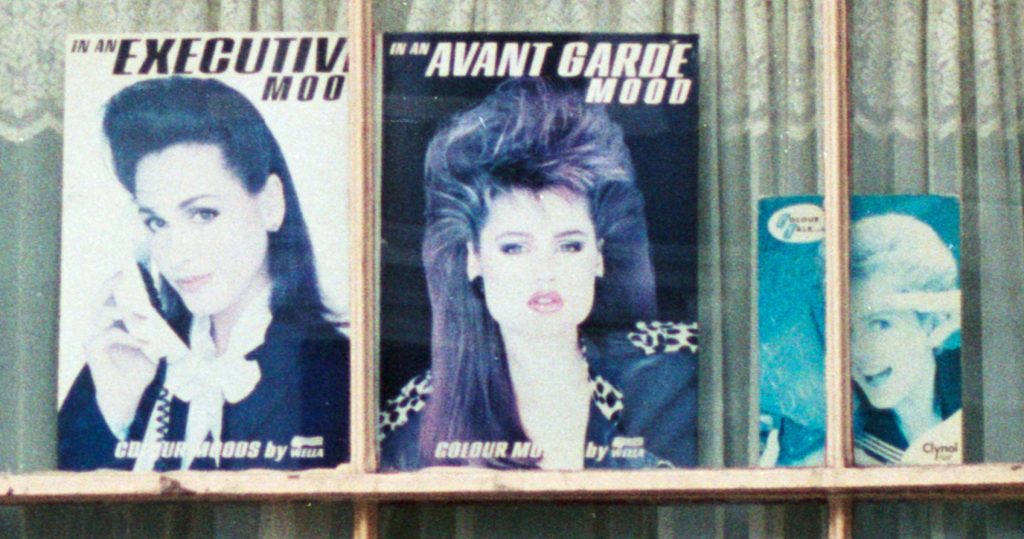

This is His & Hers Hairdressers at the Kingsland Road end of Middleton Road:

The photo is typical of the many small businesses that occupied run down Victorian shops in the 1980s, and for a hairdressers of that decade, the shop has the obligatory display of hair style photos.

This is the same shop, forty years later in 2026:

With photos of hairdressers, you can normally tell the decade of when the photo was taken by the photos in the windows, and His & Hers had photos of 1980s big hair:

Small details in the photo, such as the person inside, probably wondering why my father is taking a photo:

On the wall to the left of the shop, something that was once a common sight:

And there are details in the 2026 photo, where an earlier shop sign has been exposed:

If you go back to the 1986 photo, there is wooden boarding across the location of the above sign, so I suspect this was covered up in 1986 and dates from an earlier business.

M. Matthews is the central name. There does appear to be a shadow name, but this also looks like M. Matthews, so perhaps an earlier version of the same name. To the right is the word Tobacco, and a bit hard to make out, but to the left the letters do seem to form Newsagent.

I cannot find a reference to an M. Matthews, but the ground floor of the building has always been a shop, and searching through Post Office directories, I found that in 1899 the shop was a Confectioner, run by Miss Elizabeth Winstone, and in 1910 it was still a confectioner, but now run by Mrs Matilda Watkins.

A jump from being a Confectioner, to a Newsagent and Tobacconist, but who also probably continued to sell confectionary does seem like a natural evolution of the shop.

I have no idea when the shop changed to a hairdressers, or when His & Hers closed. In the 1986, the ground floor occupied by the hairdresser does seem to have undergone some structural alteration, as above the windows and doors, there is the full width of the panel over the name sign, and this can also be seen in my 2026 photo, where the name sign extends over the windows and two doors.

The ornate carvings typical of the sign endings on Victorian shops can also be seen in the 1986 photo, although the one of the left had been removed by 2026.

This is probably the result of the building being converted from a shop occupying the full width of the ground floor, to a building where the first and second floors became separate residential accommodation, hence the door on the left, and the door to the shop being the one on the right.

Today, the old shop on the ground floor also appears to be residential.

The shop was built in the mid 19th century as the fields and nurseries of Hackney were covered in new homes.

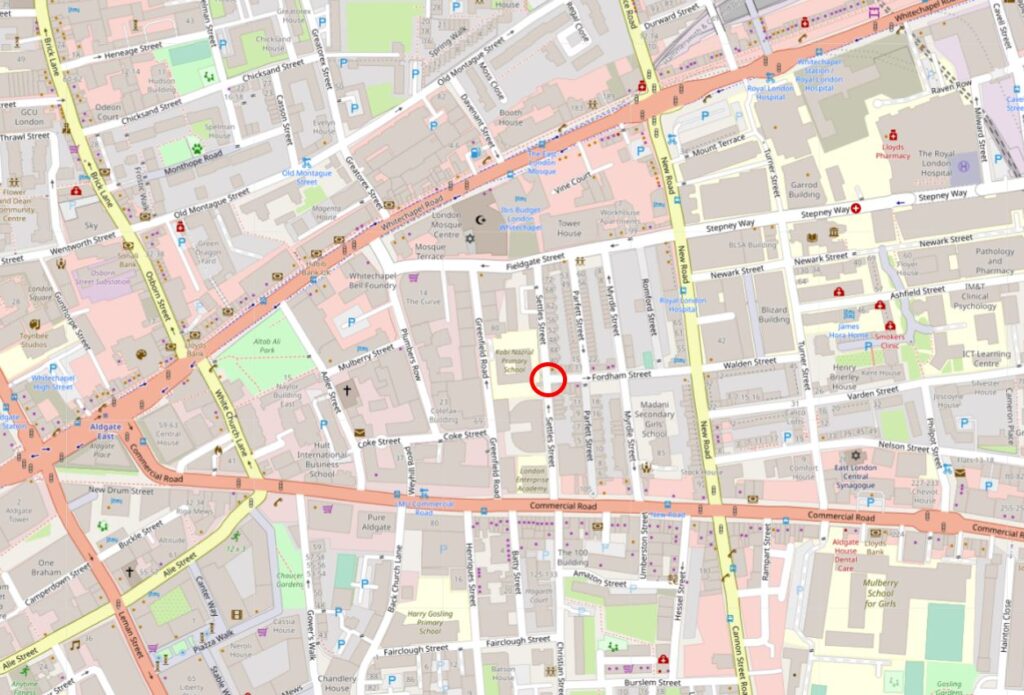

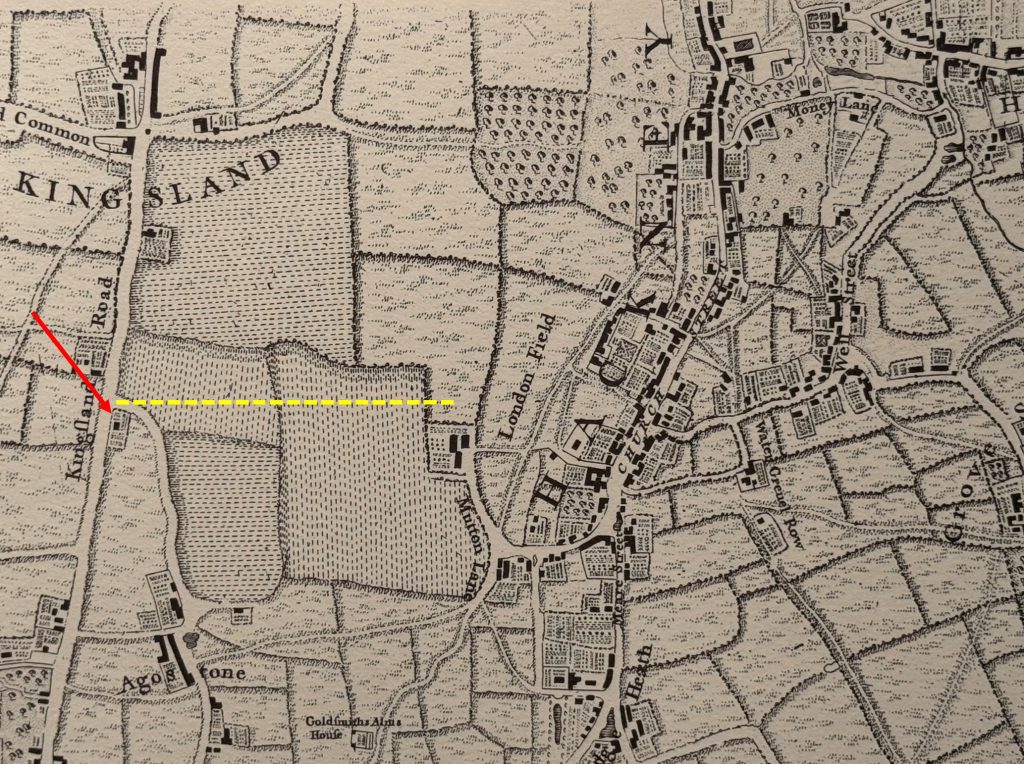

In the following map, I have marked the location of the shop with the red arrow on the left. The darker road running vertically just to the left is Kingsland Road, and to the right of the map is the edge of London Fields. Middleton Road is the street with the Hairdressers, and which runs from Kingsland Road to London Fields.

Nearly all of the straight streets in the map are Victorian housing, serving the growing numbers of middle class workers of London with aspirational new homes.

The shop was part of a street design where small businesses were distributed across new residential developments, so that people who moved out to these new homes would have access to the necessities of life within local walking distance, and this included pubs.

On the corner of Middleton Road and Kingsland Road is the Fox – a rare example of a London pub that closed in around 2018, but has recently reopened (I believe with the upper floors converted to residential):

At the very top of the corner of the building is the date 1881, and this is from when the current building dates, although there has been a pub on the site for a number of centuries.

The earliest written refence I can find to the Fox is from 1809, when on the 21st of July, there was an advert in the Morning Advertiser for the auction of five, neat, brick built dwelling houses between Kingsland Green and Newington Green. Details about the properties to be auctioned could be had from Mr. Taylor at the Fox, Kingsland Road.

When the 1809 advert appeared, much of the area surrounding the Fox was still farm land and nurseries, but the pub was here because Kingsland Road was an important road to the north from the City and would have been busy, with many of those using the road in need of refreshment.

Search the Internet for stories about the Fox, and a story about the pub being used to stash part of a £6 Million Security Express robbery in 1983, by Clifford Saxe, one of the robbers and landlord of the Fox is one of the common stories from recent years.

I cannot find a firm reference from the time that it was the Fox, an account of the robbery from the Sunday Mirror on the 1st of July 1984 on wanted criminals who were living in Spain referenced that “It claimed Saxe, 57, formerly landlord of an east London pub was the brains of the gang”. Presumably that east London pub was the Fox, but again I cannot find a direct reference from the time.

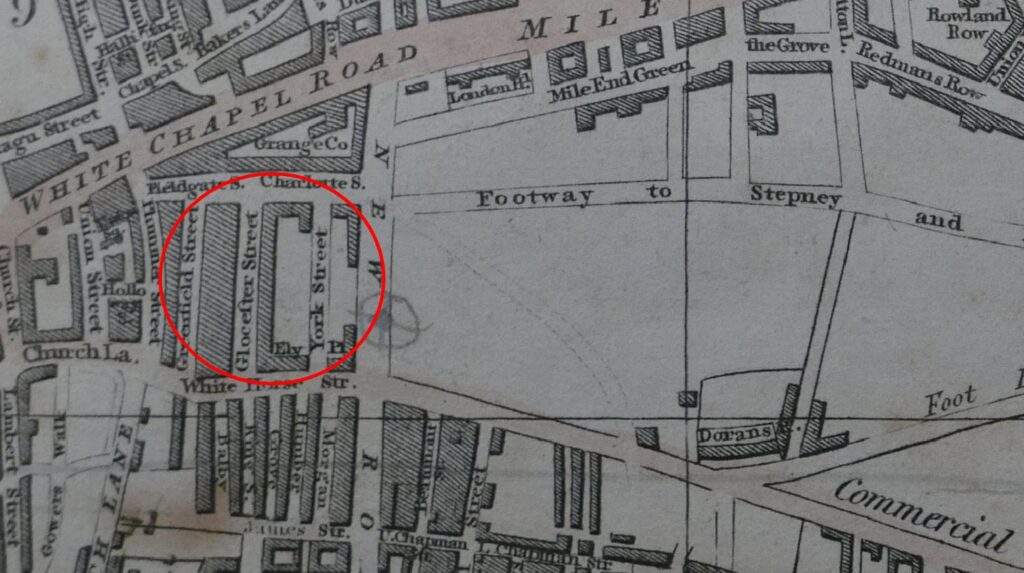

In the following extract from Rocque’s 1746 map, I have marked the location of the Fox with a red arrow. The yellow dotted line shows the route of the future Middleton Road, running from Kingsland Road to the edge of London Fields, over what was nursery land, and by 1823 would be known as Grange’s Nursery:

The 1881 rebuild of the pub must have been to transform the premises that had once been surrounded by fields, to an establishment suitable for the large population who occupied the terrace streets by then covering the fields.

The population growth of Hackney mirrors this housing development. In 1801 the population was 12,730, and a century later in 1901, Hackney’s population had grown to 219,110, and this new population needed local shops, and the confectioners / newsagents and tobacconists / hairdresser shop was part of a terrace of shops at the end of Middleton Road, with the following photo being today’s view of this terrace:

In 1899, this terrace consisted of (number 11 in bold is the shop that is the subject of today’s post):

- Number 1: John Biddle – Fishmonger

- Number 3: Mrs Stark – Baby Linen

- Number 5: John Edward Stark – Tobacconist

- Number 7&9; Benjamin Wilkinson – Chemist

- Number 11; Miss Elizabeth Winstone – Confectioner

- Number 13: Robinson Locklison – Laundry

By 1910, the terrace consisted of:

- Number 1: Walter Hart – Fried Fish Shop

- Number 3: James Arthur Mullett – Grocer

- Number 5: William Leigh – Hairdresser

- Number 7&9: Benjamin Wilkinson – Chemist

- Number 11: Mrs Matilda Watkins – Confectioner

- Number 13: John Hart – Bootmaker

The above two lists shows that in the eleven years between the two, there was a high turnover in owners and types of shop. Number 1 had changed from a Fishmonger to a Fried Fish Shop, illustrating the rapid expansion of this type of take away food across London, from what is believed to be the first such shop in east London in 1860.

Number 1 is still supplying food, as today it is the Tin Café.

The only business that is the same is the Chemist of Benjamin Wilkinson. At number 13 in 1910 was John Hart, a Bootmaker. In 1986 it was a shoe repair shop, just visible to the right of the photo at the start of the post, so in the same type of business.

Another view of the terrace, number 3 to 13:

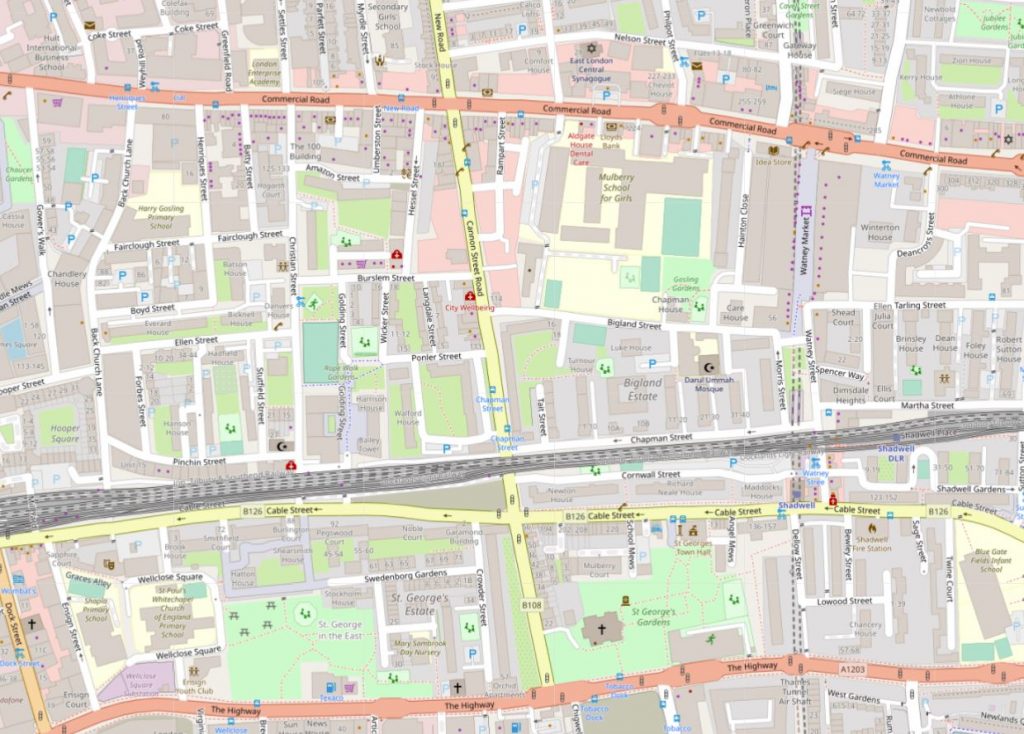

Just visible to the right of the above photo, and in an earlier photo with a train, is a bridge, which adds an unusual feature to this end of Middleton Road.

Walking along Middleton Road, under the bridge and looking back, this is the view:

The bridge carries what is now the Windrush Line over Middleton Road, and the reason for the large dip in the road is because the railway is carried on a viaduct, which runs parallel to Kingsland Road, and needs to run as a level structure, so where the railway carried by the viaduct runs across a road, the runs needs to be lowered to pass under the viaduct.

This railway was built as part of the North London extension of the London and North Western Railway, and the following extract from Railway News on the 3rd of December 1864, when the viaduct was nearing completion, explains the benefits and route of this railway:

“The London and North Western reaches the City by means of the North London extension, but the undertaking may be considered as that of the North Western.

The City extension runs from Kingsland to Liverpool Street, Bishopsgate, and is now rapidly approaching completion. The advantages of this line are very considerable.

The station is within a short distance of the Royal Exchange, the Bank of England and many offices in which the chief monetary transactions of the City are conducted. Five or seven minutes walk will bring you to Threadneedle-street, Moorgate-street, or Gracechurch-street, and all the other busy thoroughfares, lanes and courts hard by – no small consideration to the thousands of railway travellers who come from the North daily within that important radius who are anxious to economise time.

Further, this line shortens the distance between all the stations on the North London line, from Camden to Kingsland and the City by no less than five miles. At present time the North London, on leaving Kingsland, goes by Hackney, Bow, and Stepney, describing nearly three-quarters of a circle before it reaches Fenchurch Street. This detour, with its super abundant traffic and crowded junctions, with therefore be avoided by all coming west of Kingsland to the City.

The extension is about 2.5 miles in length, and proceeds almost in a direct line from its junction with the North London proper to Bishopsgate, With the exception of a cutting near the starting point it passes all the way on a brick arch viaduct which has all but been finished. Running parallel with the Kingsland-road.”

The line would go on to terminate at Broad Street Station, next to Liverpool Street.

This railway helped with the construction of the houses across the fields of Hackney, as for workers to move to Hackney, they needed an easy form of transport to their place of work, and the new railway extension was ideal. For the residents of Middleton Road, Haggerston Station was a short walk south along Kingsland Road. The station opened on the 2nd of September 1867.

Bells Weekly Messenger on the 9th of September 1867 described the new station: “NEW STATION, NORTH LONDON RAILWAY – A large and commodious new station was opened on Monday on the North London Railway, in Lee-street, Kingsland Road. The new Haggerston Station commands the neighbourhood, and also the Downham-road and De Beauvoir Town, which places are situated too far from the Dalston Junction to profit by the latter.”

The line closed in 1986 (Haggerston Station had closed in 1940 due to a number of factors including wartime economy measures and bomb damage to the station).

The station and railway along the viaduct reopened in 2010 as part of London Overground, and in 2024 the railway was renamed as the Windrush Line.

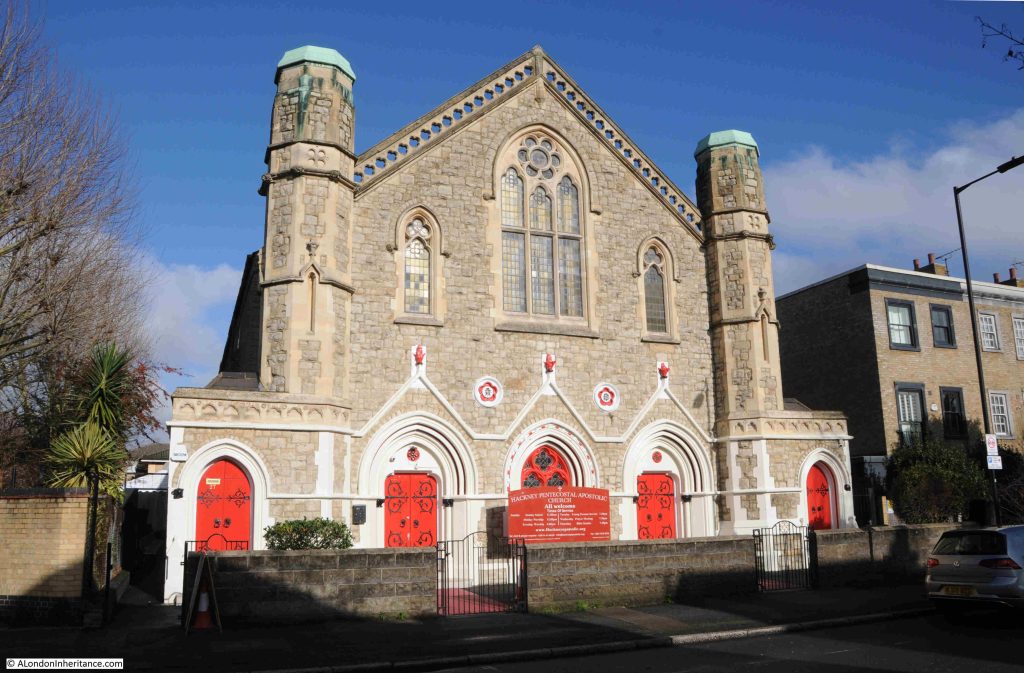

So this small part of London had shops, a pub and a station connected to the City. The other important attribute of a Victorian city was a church, and In Middleton Road is the 1847 Middleton Road Congregational Church, now the Hackney Pentecostal Apostolic Church:

Middleton Road is mainly comprised of terrace houses, but there are some interesting exceptions, such as the building in the middle of the following photo:

Which has an entry to the rear of the building named Ropewalk Mews:

I cannot find the reason for this name, and why the building is very different to the terrace houses that occupy the street.

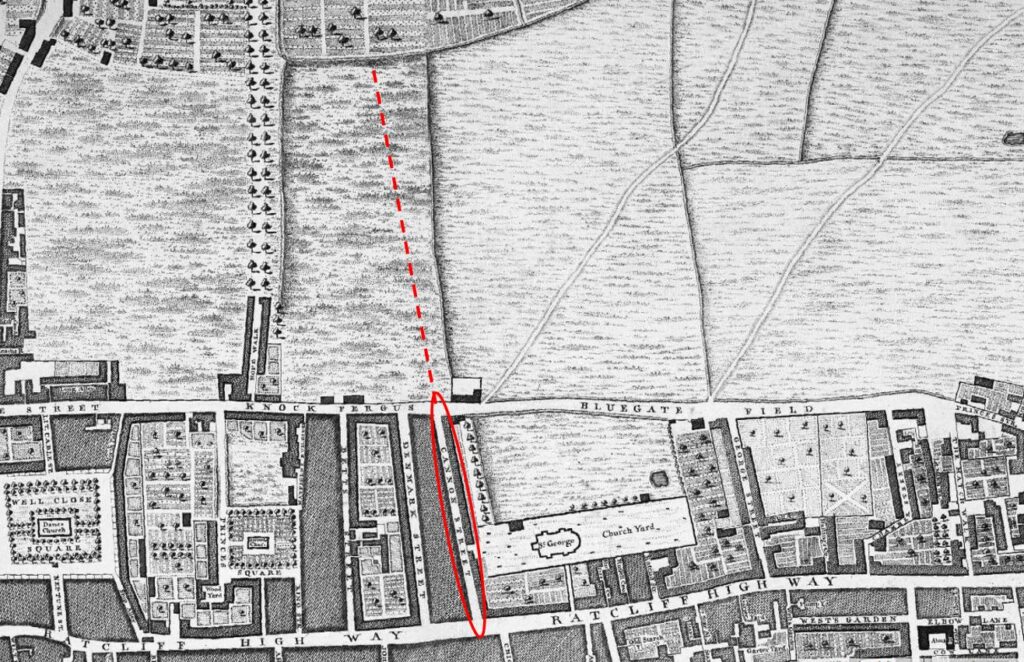

A ropewalk was / is a long length of land or covered space, where the individual strands of a rope could be laid out and then twisted to form a continuous length of rope.

London had plenty of ropewalks, but these were usually close to the Thames, as the main customer for the ropes produced would have been the thousands of ships that were once to be found on the river.

Rocque’s map of 1747 does not show a ropewalk, although the map does identify ropewalks in other parts of London. In 18th and early 19th century maps of the area, the land is shown as agricultural and a nursery, no mention of a ropewalk.

It may have been that there was a small ropewalk here to produce rope to be used in the bundling of produce from the nursery, but I cannot find any confirmation of this.

One of the architectural developments that was seen in Victorian houses of the mid 19th century was the bay window, which was a way of breaking up a terrace, and a change from the Georgian emphasis on an unbroken terrace of flat, uniform walls facing onto the street. We can see this development in the terrace houses of Middleton Street:

Another change was the semi-basement, where the ground floor is slightly raised, and reached from the streets by steps, allowing the upper part of the basement to just poke above ground level, with a space between basement window and the retaining wall to the street. This development allowed natural light into the basement, and again we can see this in the above terrace.

The 1881 census provides a view of the employment of those who moved into Middleton Road. There were a very wide range of jobs, including: Bank Clerks, Decorators, Commercial Travellers, Commercial Clerks, Boot Makers, Locksmiths, Plumbers, Stock Brokers Clerks, Stationers Assistant, Printers, Teachers, Newspaper Advertising Agents, Drapers, Draughtsmen, Watchmakers, etc. All the vast range of trades and employment types to be found in the rapidly expanding Victorian London of the late 19th century.

Where a job was listed such as a Bootmaker, these were frequently not an individual worker, rather an employer, for example at number 33 Middleton Road was George Clarke, a Bootmaker who was listed as employing 25 men and two boys.

Some of the residents had private means, for example at Oxford Cottage in Middleton Road was Fanny Smyth, listed as a widow, with her occupation as “income from interest of money”. What is fascinating about the 19th century census is how frequently people would marry later in life, and in Fanny Smyth’s household were three children, two daughters aged 31 and 21 and a son of 28, all listed as single.

Many of the houses in Middleton Road also had a Domestic Servant, again confirming that these new streets were occupied by the new middle class.

Whilst in 1881, the majority of people who lived in Middleton Road were listed a being born in Middlesex, (the historic county that from 1965 is now mainly part of Greater London), there were a very significant number of people from the rest of the country, and a small percentage from Ireland. Throughout much of the 19th century, London was expanding both in terms of employment and residents, by attracting people from the rest of the country.

More of the homes in Middleton Street in which the Bank Clerks, Decorators, Commercial Travellers etc. of 1881 would live:

Middleton Road is a perfect example of the mid 19th expansion of London, as the fields of Hackney were taken over by the houses of the growing middle class.

The shops and pub at the Kingsland Road end of the street are a perfect example of how local shops were planned as part of this expansion, and for decades served the needs of the local community.

One can imagine the early morning being busy with the working residents heading to the train station to travel into the City for their work, and in the evening, a busy pub, with the option of a stop off for fish and chips after the pub, then heading back to your terrace home in Middleton Road.

When writing these posts, I often have music on in the background, and for this post it was YouTube, as it has a random playlist based on what I have listened to before, and a track I have not heard for many years came up, the 1982 Lucifer’s Friend by the Rotherham / Sheffield band Vision.

The His & Hers Hairdressers was photographed in 1986, and the track by Vision is a perfect example of brilliant 1980s music, including the type of hair styles that you may have been able to get in His & Hers:

David Bowie Centre and V&A East Storehouse

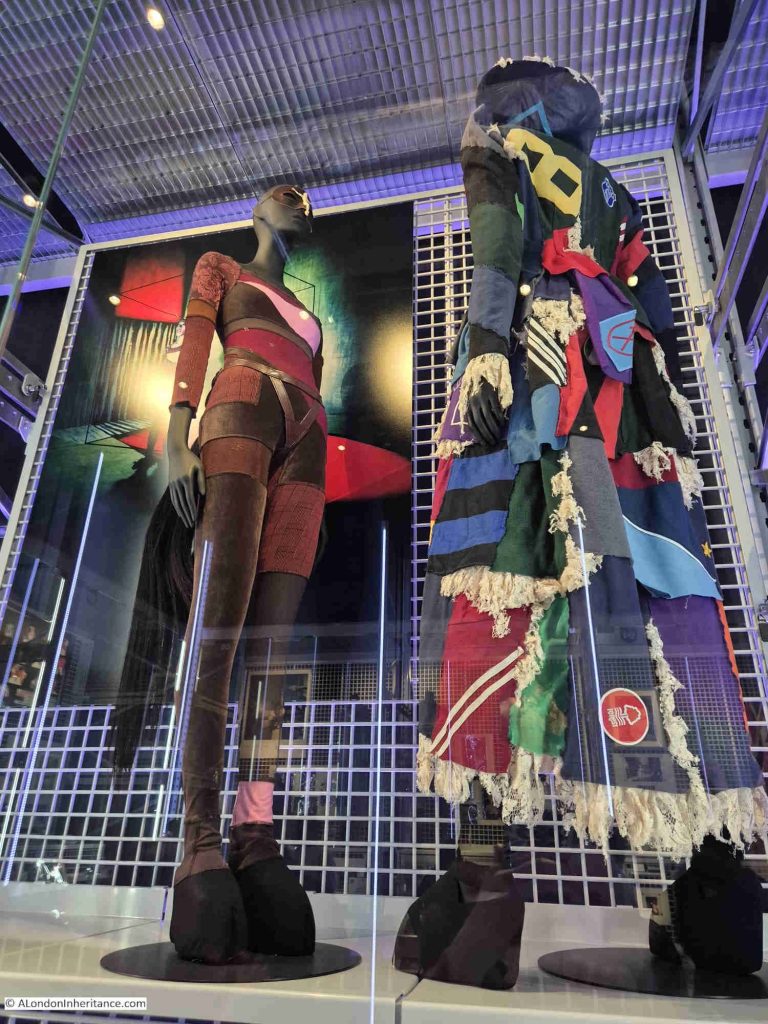

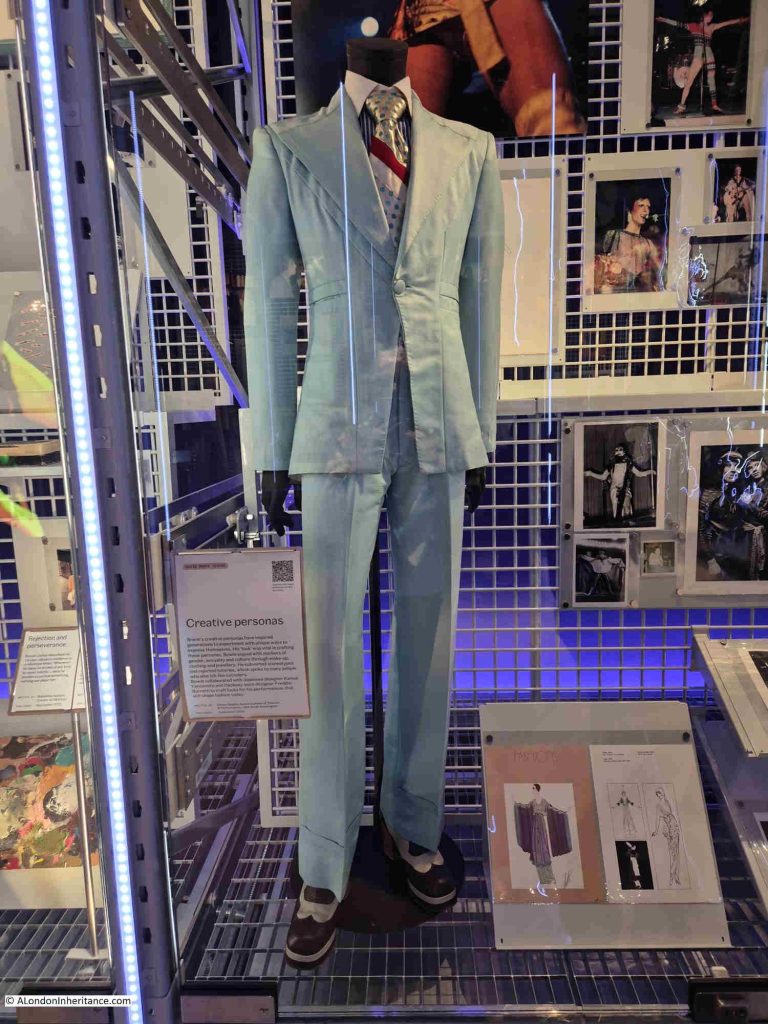

Last week, we went to have a look at the small David Bowie exhibition, which forms part of the David Bowie archive held by the V&A. It is located at the new V&A East Storehouse at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park:

It is a small, but interesting exhibition of some of the costumes worn by Bowie, photos, song lyrics, ideas for films, plays etc.

The Bowie exhibition and archive is a small part of the Storehouse, which is home to a vast collection of items not on display in the main museums.

You are free to wander around the walkways on several levels between racks of items collected over very many years:

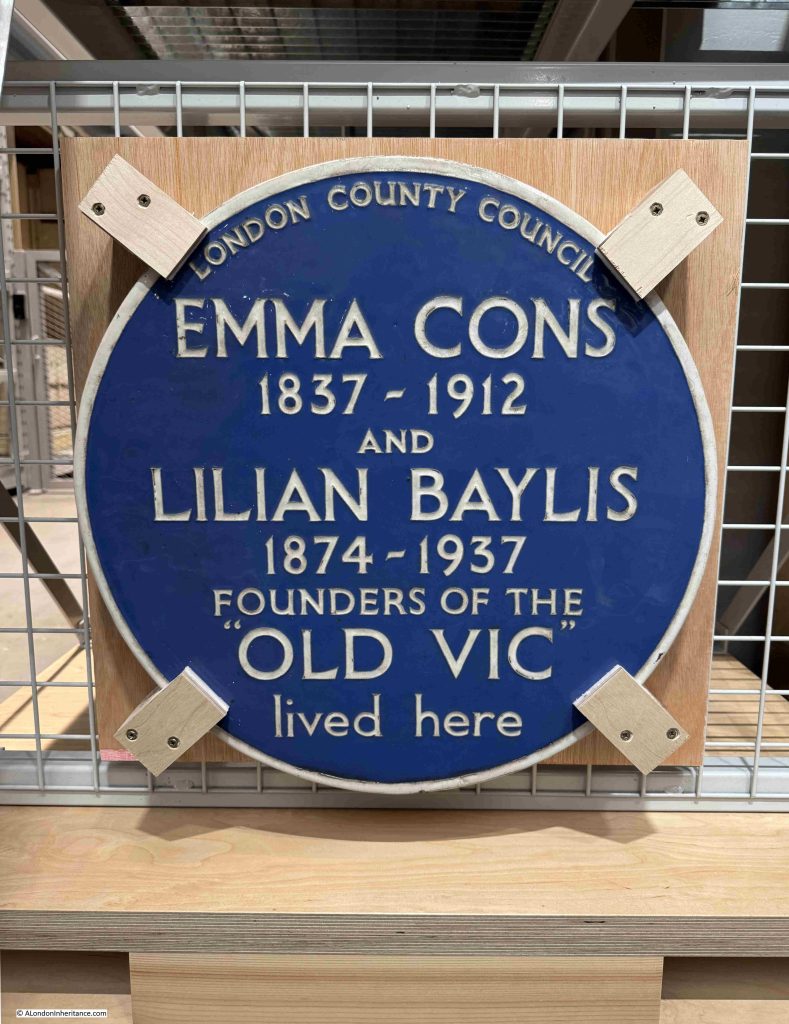

There were a number of London related items on display, for example a London County Council plaque recording that Emma Cons and Lilian Baylis lived here:

The plaque dates from 1952 and was installed on the house at 6 Morton Place, Stockwell. The house was demolished in 1971 and the plaque was saved with the intention that it would go on display in the V&A Covent Garden Theatre Museum. The Theatre Museum closed in 2007, and the plaque is now on display the V&A East Storehouse.

The V&A also has a number of items relating to Robin Hood Gardens, the social housing estate in Poplar, east London, including a section of the west block, to preserve the architectural vision.

One of the items on display is a collage from the Robin Hood Gardens Project:

And some of the fittings from Robin Hood Gardens:

The V&A East Storehouse is a fascinating way to display part of the collection that would not normally be on display in the V&A museums, and is well worth a visit.