Thanks for the feedback to last week’s post. The pub at the top of the stairs leading down to the Thames, next to Westminster Bridge Road was identified as the Coronet, and there is a good drawing of the pub and the stairs on the Closed Pubs site. It was good that I did not get any comments or e-mails that the bronze box beneath the foundation stone of County Hall has been removed, so hopefully it is still there for archaeologists in the distant future to dig up.

For this week’s post, I am in East London, looking for the location of a shop in Fordham Street, photographed here in 1986:

The same location today. The old general stores type of shop has been replaced by the Algiers Barber and Café:

The 1986 photo is typical of the type of shop. Goods piled high in the window, bread, bottles of Fairy Liquid and Woodbines advertising running along the top of the window.

No idea whether that is a customer entering the shop, or the owner locking or unlocking.

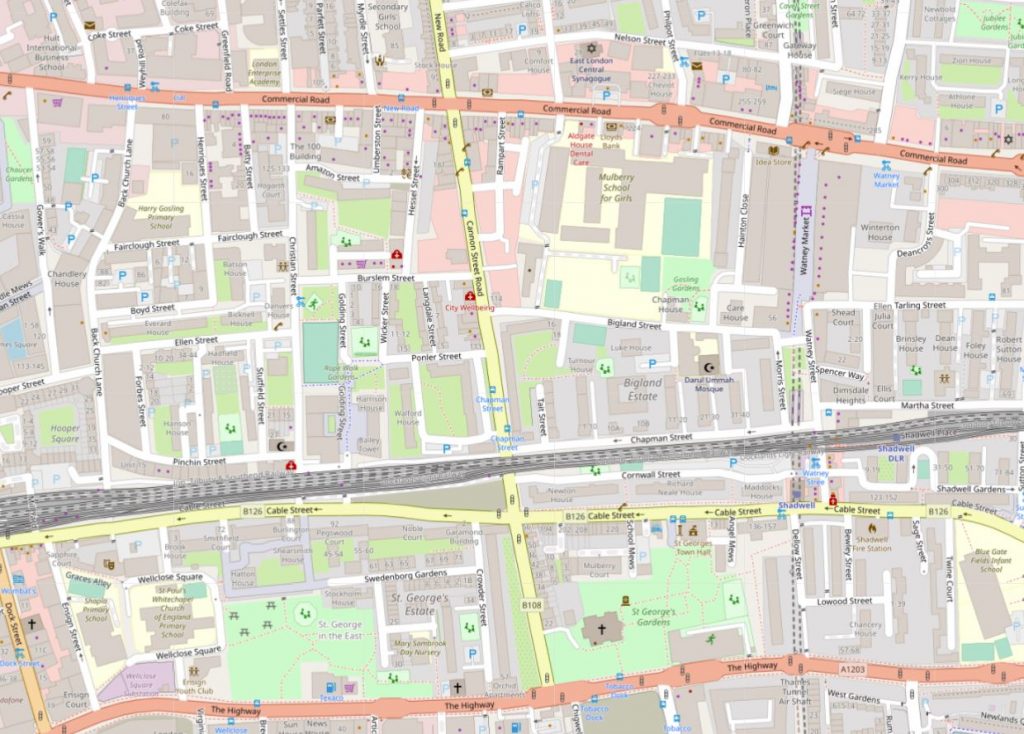

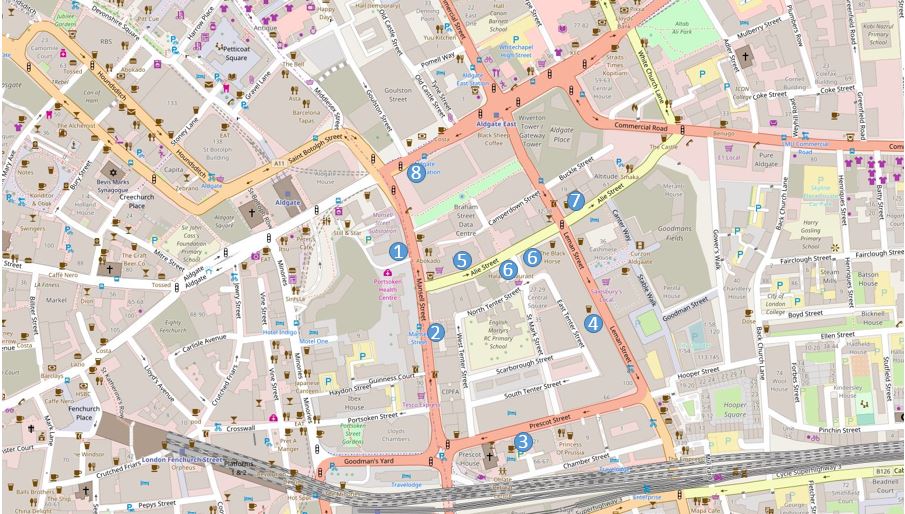

Fordham Street is in the heart of east London, roughly half way between Whitechapel and Commercial Roads. The street leads from New Road which is a main street leading between Whitechapel Road and Commercial Road, and is part of a residential area that has long housed the changing populations of east London.

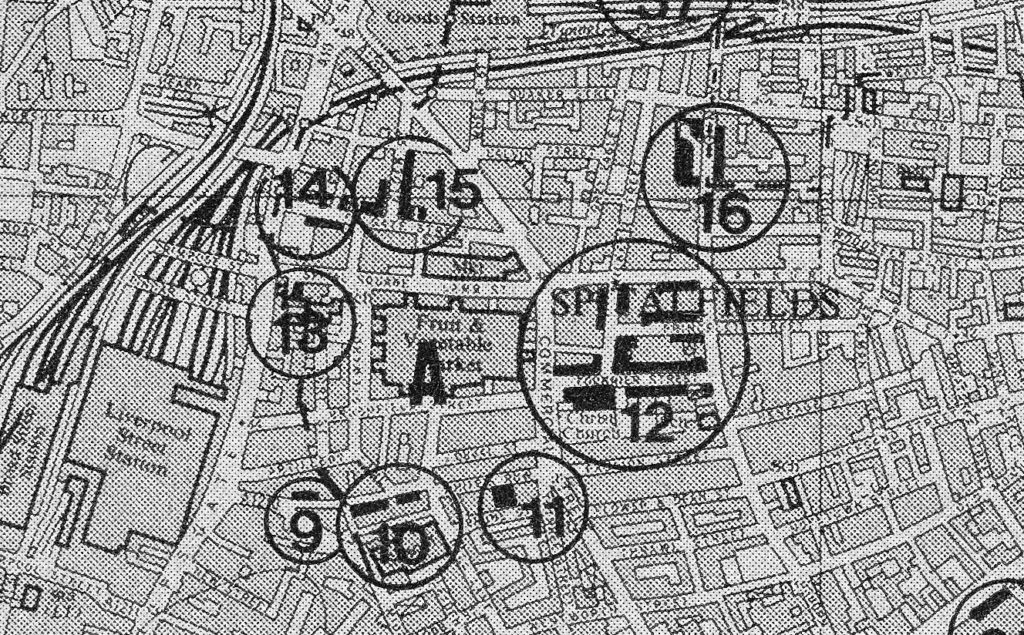

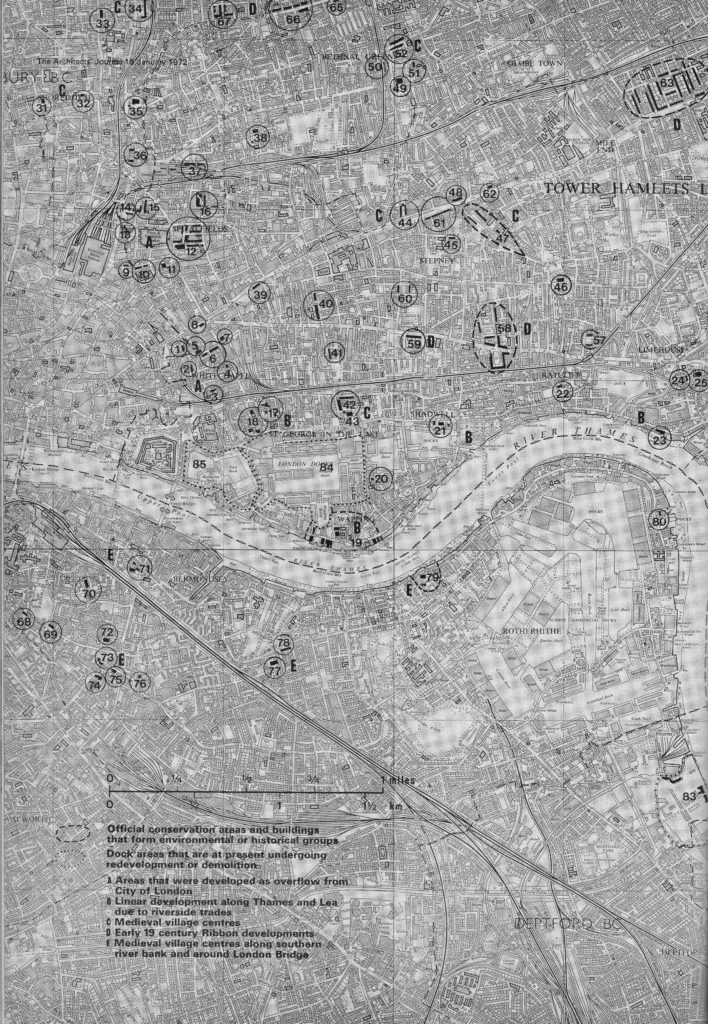

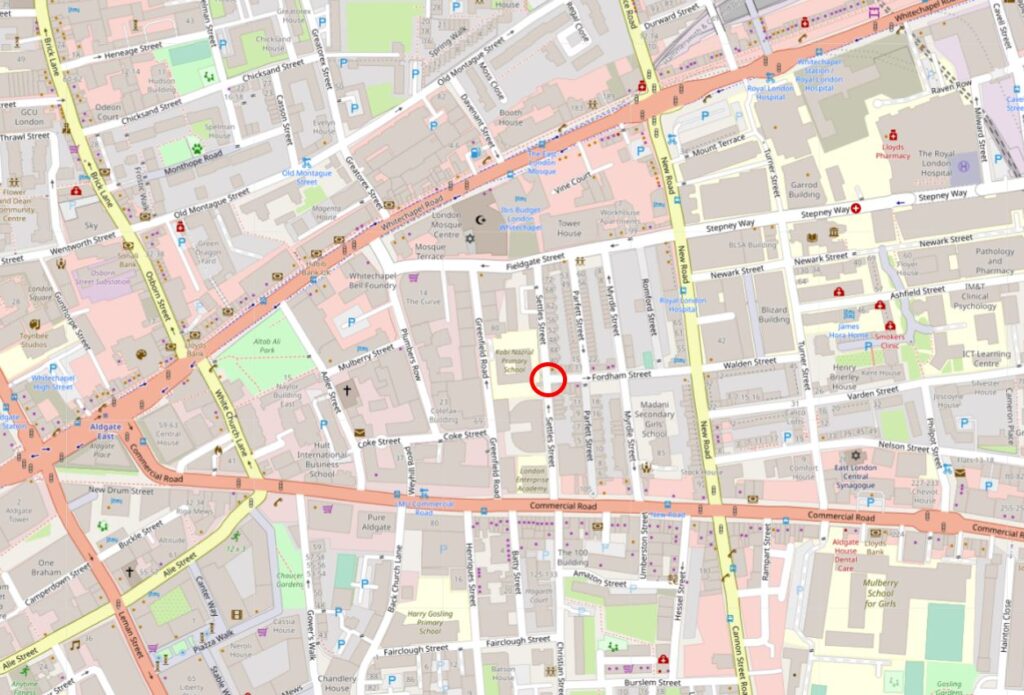

In the following map I have circled the location of the shop photographed at the top of the post:

A view of the corner location of the shop, at the end of a short terrace of houses:

Although a relatively short street, as was typical in east London of old, the street had two pubs, both now long closed. On the corner opposite the shop is the building that housed one of the pubs:

The pub was the Bricklayers Arms. I can find very little information about the pub, and there are only a couple of newspaper reports that mention the Bricklayers Arms. The first is when a 19 year old labourer, Frederick Perrie was sentenced to six months hard labour after trying to use a counterfeit florin in the pub in 1893.

Throughout the first decade of the 20th century, Friday evenings seem to have been the time when the East London (Jewish) branch of the London Central Council met in the pub. Regular adverts about the event featured in newspapers. The licensee at this time appears to have been Isaac Ernest Marks.

The last reference to the pub is in 1911 when Isaac Ernest Marks had his license renewed. It does not appear to have stayed open long after 1911 as Closed Pubs suspects the pub was closed by the 1920s, and there are no newspaper reports mentioning the pub after 1911.

Pubs such as the Bricklayers Arms would have served those living in the densely populated terrace housing that lined the streets around Fordham Street. Whilst many of these have been demolished, some remain, although the following photo shows the challenges of taking photos with a low winter sun on a bright day:

Many of the corner shops in Fordham Street have survived, and have changed over the 20th century to serve the changing population of east London:

The second pub in the street was the Duke of York. The Bangla Super Store on the corner of Fordham Street and Myrdle Street now occupies the building that was once the pub:

The Bangla Super Store maintains the tradition of a corner shop stacked high with a wide range of goods for the local community.

Rather strangely, I cannot find any newspaper report mentioning the Duke of York, and cannot find any record as to when the pub opened or closed. It is marked as a Public House on the 1894 Ordnance Survey map of the area, and the building has the large, flat corner on the upper floors, so typical of 19th century pubs where their large pub name / advertising signs were located.

Myrdle Street runs across Fordham Street, and the straight lines of this network of streets indicate that they were laid out as part of a significant development of the area, however the street plan that we see today appears to be the second since the fields that once covered the area were built on.

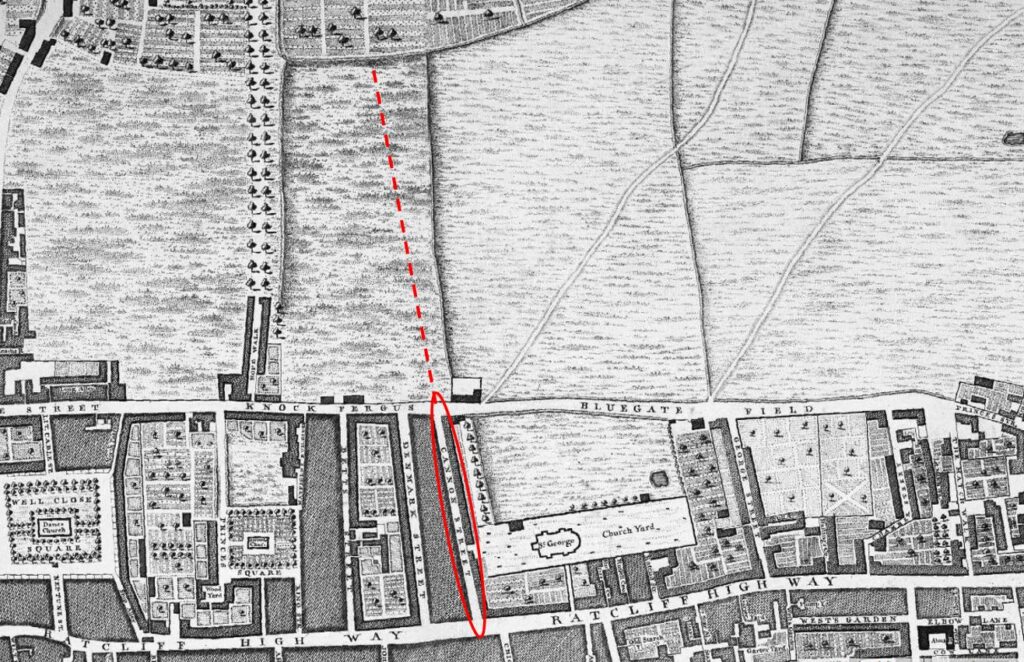

In 1746, John Rocque’s map was showing the area now occupied by Fordham Street as a field, surrounded by other fields, ponds and cultivated land (the red line indicates the future location of Fordham Street):

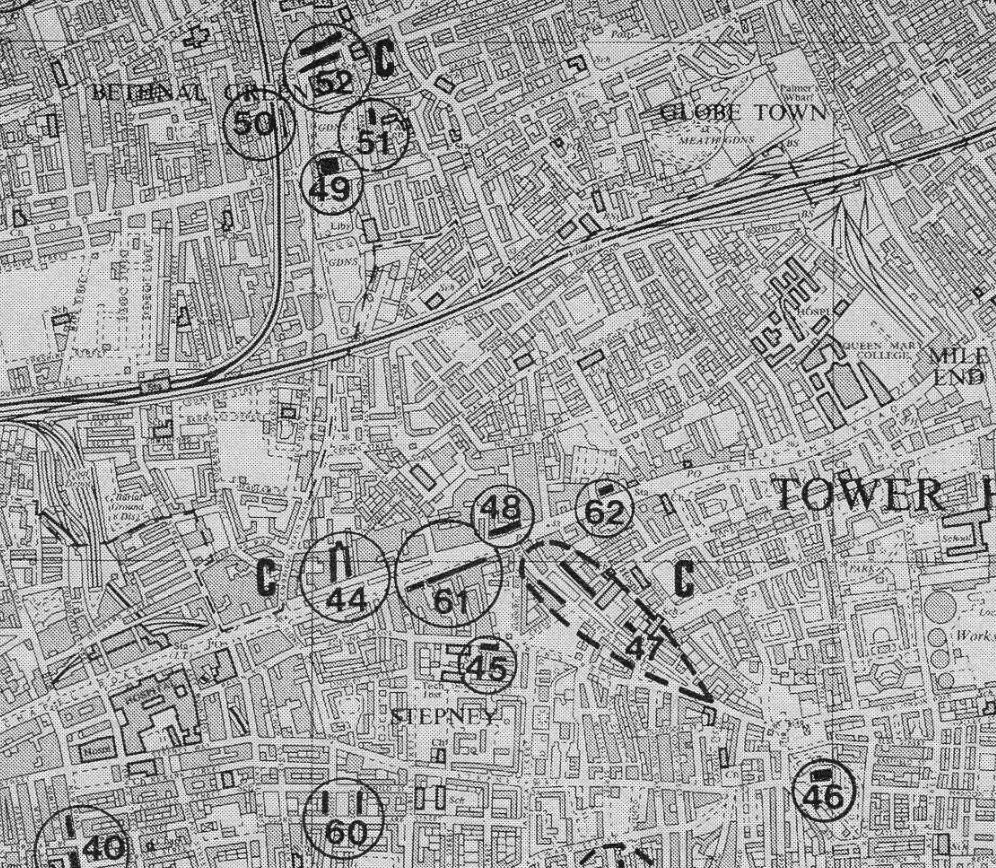

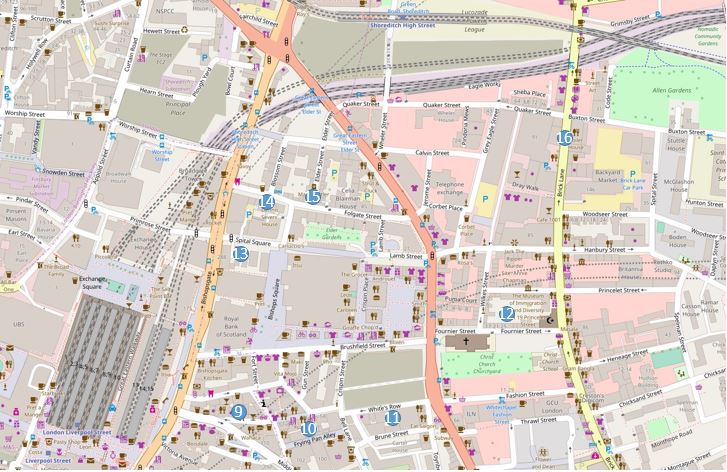

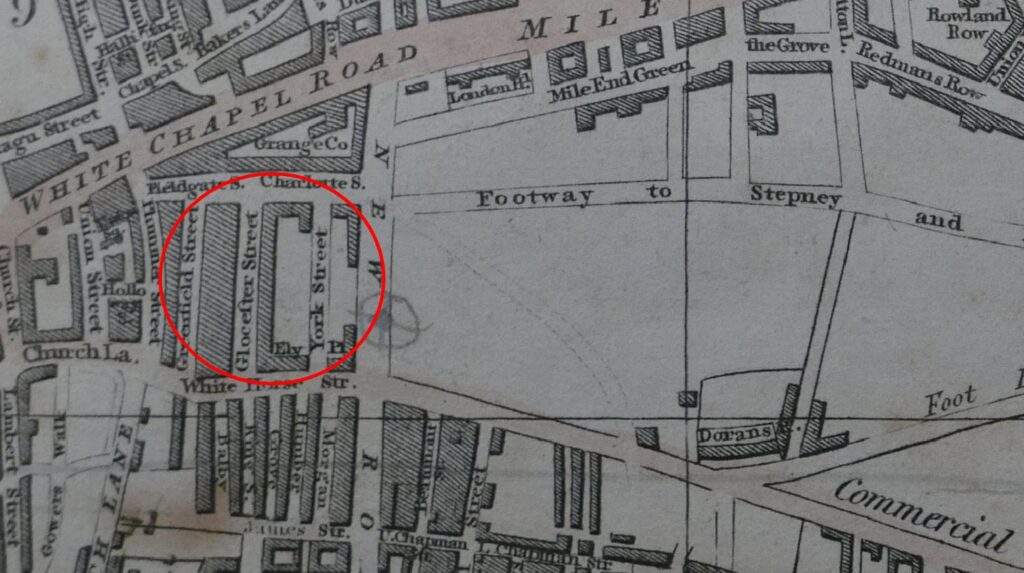

The following is an extract from the 1816 edition of Smith’s New Plan of London. I have ringed the area now occupied by Fordham Street and surrounding streets:

Comparing with the map of the area today (see below), and the streets, along with their street names are very different. To confirm the location, Whitechapel Road runs along the top of both maps, the start of the Commercial Road development runs along the lower part of the 1816 map, and one of the few consistent street names is Fieldgate Street which runs just south of Whitechapel Road in both maps.

New Road can be seen in both maps, new as this was a major new road built as part of the development of the area.

I cannot find exactly when Fordham Street was initially developed. It is shown in the 1894 OS map. The first newspaper reports which mention the street date to the 1880s, including one from 1886 which advertises a building plot available to be leased in Fordham Street.

Charles Booth’s poverty maps include Fordham Street, with the occupants of the street falling within the classification “Mixed. Some comfortable, some poor”. There was one area described as “Very poor, casual. Chronic want” on part of the land now occupied by Fieldgate Mansions (see further in the post). The street may then date to the early 1880s, however this does seem rather late.

I like that the Footpath to Stepney in the 1816 map is now the Stepney Way, to the upper right of the following map.

So the streets we see today are not those from the original development of the area, and were built in the decades following the 1816 map. Interestingly, in 1816 there was a York Street roughly where Myrdle Street is today, where the Duke of York pub was located on the corner with Fordham Street, so this lost pub may have been named after the name of the original street.

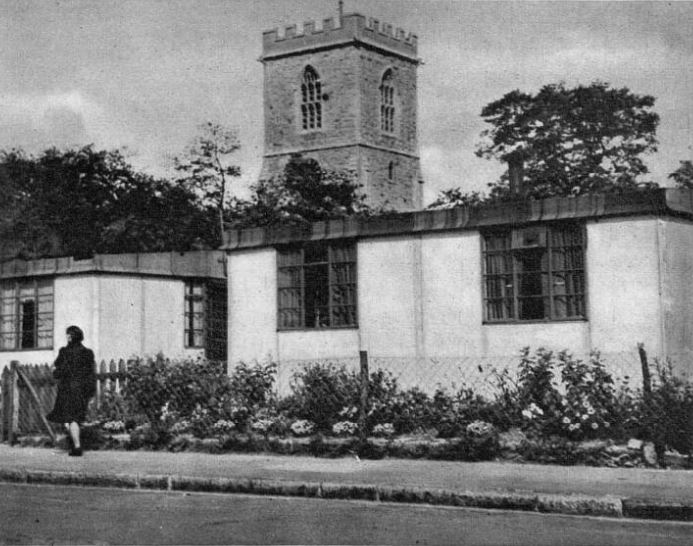

Myrdle Street was a long run of terrace houses, but one side of the street has been replaced by Fieldgate Mansions:

Fieldgate Mansions is a large complex of tenement dwellings that extend along Myrdle Street and further back towards New Road. They were built between 1903 and 1907 to replace the much smaller terrace houses that ran the length of the street. They take their name from Fieldgate Street which runs at the northern end of Myrdle Street.

The original tenants were mainly Jewish immigrants, which probably explains why meetings of the East London (Jewish) branch of the London Central Council were held in the pub at the end of Fordham Street.

Post war, the blocks were neglected by their landlords, some had suffered bomb damage, and by the early 1960s prostitution was a considerable problem in the area.

Many of the apartments in the blocks were empty by the late 1960s and 1970s, and were occupied by squatters campaigning for the restoration and use of derelict property.

They were redeveloped during the 1980s and it is the restored Fieldgate Mansions that we see today:

Unlike the Duke of York pub, there are plenty of references to Fieldgate Mansions in the press, that tell of everyday life, and the challenges of those who lived here.

On the 4th of December 1942, the East London Observer has a Naturalization Notice, where “Notice is hereby given that H. LEVY of 48, Fieldgate Mansions, Myrdle Street, E.1. is applying to the Home Secretary for naturalization, and that any person who knows any reason why naturalization should not be granted should send a written and signed statement of the facts to the Under-Secretary of State, Home Office, S.W.1.”

On the 5th December 1941, Fieldgate Mansions were advertising for “two fire watchers, good references essential”. An important role where fire watchers would look out for fires started by incendiary bombs and then do their best to extinguish fires before they took hold. This was a role my grandfather had in his flats.

A strange case reported on the 31st March 1944 was when Morris Lakin, 32, a traveler of Fieldgate Mansions was in court accused of receiving stolen goods, described as property of the Canadian Army. A strange combination of “five revolvers, 83 rounds of ammunition and 63 pairs of woollen socks”. He was also charged, along with two others of receiving a “quantity of cosmetics, a wireless set and an Eastman cutting machine”.

The tenants of so many east London apartment blocks were subject to rent rises, and there were frequent strikes where tenants refused to pay their rent. On the 4th of July 1939, one rent strike ended and another began “Sixty-four tenants of Fieldgate Mansions, who have withheld their rents for 20 weeks, have reached agreement with their landlord. Rent reductions are to be made from May 1st, some amounting to 3s a week. At Linden Buildings, Brick-lane, Bethnal Green, 68 tenants started a rent strike yesterday”.

Just five years where within Fieldgate Mansions we have rent strikes, protecting the community by fire-watching, stolen goods, and H. Levy’s application for naturalization.

Myrdle Street crosses Fordham Street and on the south-western corner of the junction is another business housed in what was an original corner shop. The wooden decoration just visible around the top and to the right of the current shop signs demonstrates that this has long been a corner shop.

The following photo shows the view west, along Fordham Street at the junction with Myrdle Street. The towers of the City can be seen in the distance.

Fordham Street is a very ordinary east London street, but it can tell so much about how the area has developed from the field of the 18th century to the network of streets we see today.

The demise of east London pubs, changing populations, and snapshots of the lives of people who have made this part of the city home for a brief few years.