The Albert Memorial in Kensington Garden’s is far more than just a memorial to Prince Albert. It is also an embodiment in stone of the Victorian world view. The gleaming gold statue at the centre provides the focal point, but look around the memorial and we can catch a glimpse of how the Victorians saw the world.

The memorial was photographed by my father using Black & White film on a gloriously sunny winter’s day in 1948:

The same view on a rather overcast late summer day, 71 years later in 2019:

A landscape photo to get a wider view of the base of the memorial:

And the same view in 2019:

As could be expected, the view is almost the same across 71 years. The Albert Memorial, and the immediate surroundings are the same, as are the majority of the trees in the background.

With London’s ever changing built environment, it is good that there are some places where you can look at a view which has not changed for many years.

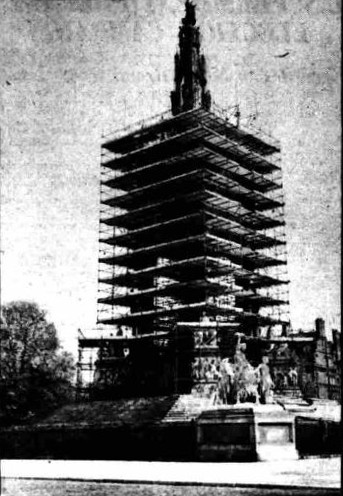

The only difference to the memorial is the lack of a cross at the top in the 1948 photo. This was part of the original build, and is part of the memorial today, but was missing in 1948. Bomb damage had knocked off the cross in 1940, and caused damage to the overall memorial. The cross had been replaced by 1955, along with repairs to the overall structure. The following photo shows the Albert Memorial covered in scaffolding in 1954 during post war restoration work:

The Albert Memorial as it appeared soon after completion in 1876, with the gold cross at the top of the monument (Image © Victoria and Albert Museum, London).

Prince Albert died on the 14th of December 1861 at the age of 42. There had been plans for a statue of Prince Albert in Hyde Park following the 1851 Great Exhibition, however these had not progressed and the prince had made it known that he was not in favour of statues of himself.

After his death, there were many memorials planned and implemented across the country, but the one that attracted the majority of attention, was for a memorial in London. Hyde Park seemed the obvious location as this would build on the original plan for a statue following the 1851 Great Exhibition, however the location would be moved to Kensington Gardens, opposite the Albert Hall which was completed in 1871, a few years prior to the Albert Memorial.

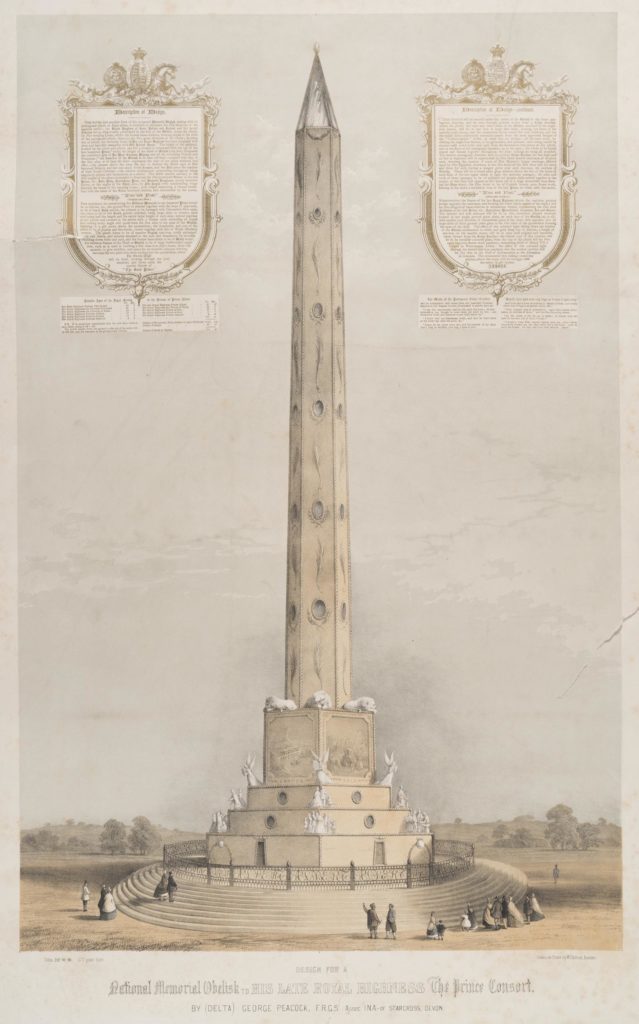

In 1862 a committee was formed to raise funds for a memorial, and proposals were submitted for a memorial from a range of sculptors and architects. Many of the initial designs featured an obelisk. The following is one such early design for the Albert Memorial (Image © Victoria and Albert Museum, London):

The obelisk idea would be dropped in favour of designs that featured a central statue of Prince Albert, surrounded by ornamental statues. Options included the central statue being both covered and open.

Proposals for the memorial took on more of an architectural influence, and one of the submissions was by George Gilbert Scott, who commissioned a model of his proposed design from Farmer and Brindley of Westminster Bridge Road. The model in the following photo shows a Gothic inspired canopy, with spire and cross enclosing a gilded statue of Prince Albert (Image © Victoria and Albert Museum, London):

Scott’s plans were included in plans submitted to Queen Victoria for approval, and in 1863 Scott’s plans for the Albert Memorial were approved and given the go-ahead, including a sum of £50,000 voted by Parliament to add to the sums already raised by subscriptions.

Construction of the overall Albert Memorial was divided across a number of builders and sculptors.

The builder John Kelk was responsible for the central memorial. The initial sculptor of the central statue of Prince Albert was Baron Carlo Marochetti, however Marochetti died before the work was complete, and the sculptor J. H. Foley was chosen to complete the statue of Prince Albert.

The gilding of Albert’s statue was rather controversial after being unveiled. The Globe on Thursday, March 9th 1876 reported:

“The statue of the Prince Consort, facing the Albert Hall, appeared uncovered this morning, glittering in all the splendour of gold. It is most difficult to judge of the artistic value of the work, from the fact that it is very dazzling to the eye, but this result of the work, so long waited for, does not upon a first glance leave a very favourable impression.”

In addition to Prince Albert, there are eight statues to the practical arts and sciences on the pillars and niches of the canopy. There are also eight works surrounding the central canopy.

Four, mounted at each corner on plinths extending from the base of the central canopy represent the “industrial Arts”. These are Agriculture, Manufactures, Commerce and Engineering.

The four outer works, at the corners of the railings that separate the memorial from the granite steps leading down to the street, represent the four corners of the globe – Europe, Asia, Africa and America.

All of these works were created by a different sculptor, but in overall form and size had to conform with Scott’s overall design for the memorial.

These eight surrounding works were to represent the interests to which Prince Albert devoted his life, along with the global view of the British Empire, and the memorial was to be viewed as a whole, not just the central statue of Prince Albert.

Construction of the memorial was over a number of years, with the gilded statue completing the memorial in 1876. As well as the newspaper report on the controversial gilding of the statue, completion finally allowed the memorial to be viewed as a whole, as this report from the Globe on the 10th March 1876 describes:

“The Albert Memorial has at last been completed, and was yesterday dedicated to the public, the statue of the Prince having been uncovered without any attending ceremony.

It is scarcely possible as yet to fairly criticise the effect which the final addition to the monument produces. The colossal statue of the Prince dazzles the eye from the brilliancy of the fresh gilding, and makes the rest of the structure appear rather to disadvantage in point of contrast. An English climate and a city atmousphere will, however, soon correct these defects. Even as it is, the merits of the statue are apparent. hitherto, the memorial had a straggling and incomplete appearance. the several groups which composed it, admirable in point of detail and as separate pieces, wanted concentration and unity. The superb designs representing the four quarters of the world had no structural identity with the architectural part of the monument, and seemed isolated and disconnected. the public can now judge how happy was the idea of giving to the central figure a gilded surface. This mass of glowing lustre attracts the eye at once, and by its importance reduces all the rest of the sculpture to its true subsidiary position.

The gilding of the figure connects the gilding of the roof and shrine above with the gilding of the railwork that forms the extreme limit beneath, and thus makes the whole harmonious. It is necessary, perhaps to insist a little on this advantage, for other points have necessarily been sacrificed to attain it.

A gilded statue can neither be as satisfactory in resemblance, taken by itself, as bronze or as marble. But the true view of the memorial is to regard it as an example of decorative art. Its perfection consists in its entirety. The shrine is as valuable as the treasure which it encloses. We are not to treat the memorial which “Queen Victoria and her people have erected for posterity as a tribute of their gratitude” simply as a statue of the Prince Consort, with suitable surroundings. That would be to miss the whole scheme and design of its originator.

The monument of the Prince happily illustrates those arts and sciences which the devotion of his life nobly fostered in the midst of a not too enlightened people.

The whole structure is as much a memorial of Prince Albert as the statue which recalls his well-known presence.

We see it at last completed after a lapse of ten years, and welcome it as an answer to that piece of flippant generalisation which proclaims that nothing in this country which attempts to be artistic can be successful.”

Around the base of the central canopy and out to the railings that surround the memorial are eight groups of sculpture. The inner four represent the “Industrial Arts” and the outer four represent the four corners of the globe. Each work was by a different sculptor.

Three of my father’s photos were of these works. Photographed on a sunny day, with the sun in the right position, and in black & white film, which after looking at my colour photos, I am of the view that black & white is one of the best ways to photograph this type of work.

Europe:

Another view of the Europe sculpture grouping with the central canopy in the background:

Africa:

On a rather dull, late summer’s day, I photographed all the sculpture groupings, starting with the outer works of four corners of the globe.

This is Asia by John Henry Foley:

Europe by Patrick Macdowell:

The figures in each of these works were symbolic of the countries they represented, so in the Europe grouping above, the central figure as viewed from this perspective is that of France – a military power, holding a sword in the figure’s right hand, and a laurel wreath in the left hand.

America by John Bell:

Africa by William Theed:

Now come the inner groupings, the industrial arts, starting with Agriculture by Calder Marshall:

Manufacturers by Henry Weekes:

Engineering by John Lawlor:

Commerce by Thomas Thornycroft:

There are further works, around the base of the podium with a continuous frieze of reliefs which represent poets, musicians, painters, architects and sculptors. The frieze was split between two sculptors, J.B. Philips was responsible for architects and sculptors and H.H. Armstead for the rest of the works.

Detail of part of the musicians section of the frieze:

Each individual is named either above or below the figure.

Detail from the musicians frieze:

The Albert Memorial is a complex object, and was both loved and criticised when revealed as a completed work.

The gilding of the statue of Prince Albert, the arrangement of the surrounding sculptures, the sculptural work and interpretation of the theme of each work. The Gothic canopy. The whole memorial needs to be considered as a single piece of work, and was intended to reflect the interests of Prince Albert. The choice of characters and their interpretation reflects the mid Victorian outlook on the world, and the central frieze acts as an encyclopedia of those considered important in their respective cultural fields.

Towards the end of the 20th century, the Albert Memorial was in a critical state.

The statue of Prince Albert had been blackened during the First World War, to prevent it being a target during Zeppelin raids. The surrounding sculptures were damaged, and the whole memorial was in need of cleaning and repair.

A decade long restoration of the memorial was completed in 1998, which included Prince Albert being re-gilded. He now shines in the sun, as intended, as he looks out over south Kensington.