One of the pleasures of walking in London is turning off a very busy road and finding a very different place. The Cromwell Road in west London carries four lanes of traffic in and out of London, with the road being the main road route from Heathrow Airport to central London. It is the A4 that leads to the start of the M4 motorway. Lined with hotels, including the world’s largest Holiday Inn hotel. The road also passes the Natural History and V&A museum.

However, turn off the Cromwell Road opposite the Holiday Inn and after a four minute walk you will find one of the most picturesque of London’s mews.

This is Kynance Mews, which my father photographed in 1986:

The same view thirty five years later:

The mews are a favourite of “travel and lifestyle” bloggers as well as on Instagram. I resisted the temptation to take any selfies whilst posing in front of the many picturesque locations along the mews.

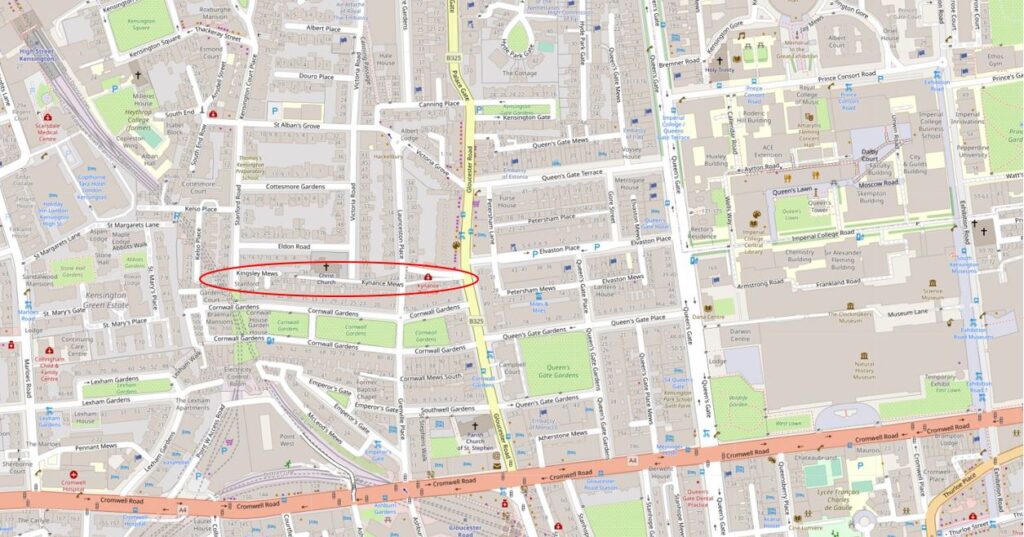

I have marked the location of Kynance Mews with the red oval in the following map (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

Cromwell Road is the large road running across the bottom of the map.

As well as finding the location of my father’s photo, I took a short walk to have a look at a couple of the streets in the area. I have marked the route on the following map, with the location of the two photos at the top of the post marked by the red circle (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

Kynance Mews starts on the Gloucester Road, where an arch can be found leading into the mews. The road on the immediate right of the entrance to the mews is called Kynance Place.

Looking through the arch and we can see Kynance Mews disappearing into the distance.

Kynance Mews is a few feet lower than Kynance Place and separated by a high brick wall.

Kynance Mews date from the 1860s, and owes its existance to the estate that was built to the south. The name is also not the original name for the mews.

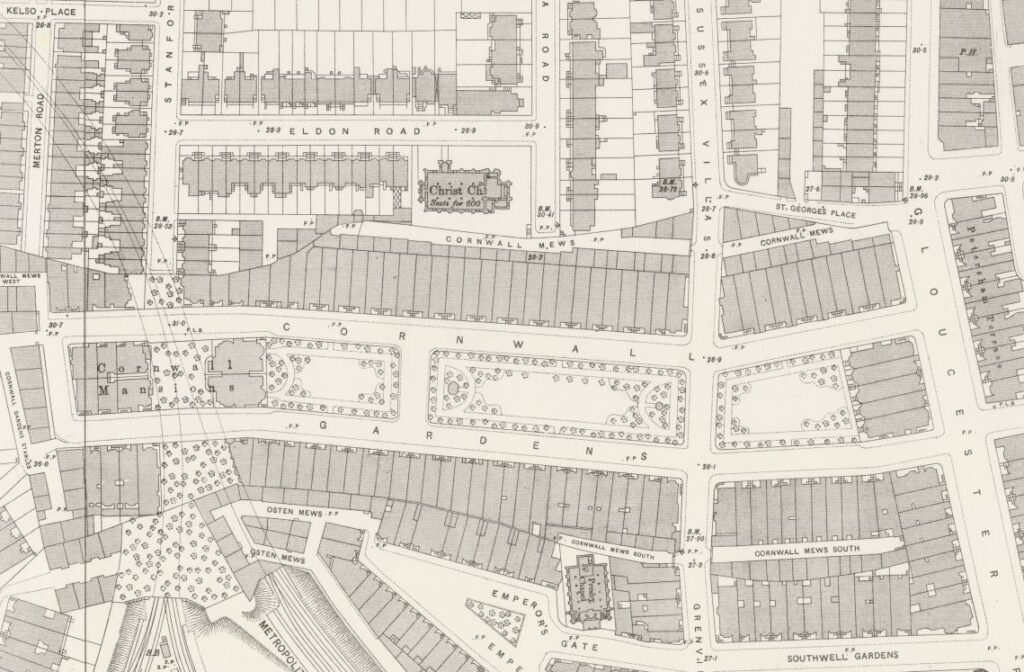

The following extract from the 1895 Ordnance Survey map shows the area thirty years after completion. In the centre of the map is the centre of the development – Cornwall Gardens, and behind the large houses on the north of the gardens is Cornwall Mews (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’).

The central area from Gloucester Road on the right and the edge of the map on the left was owned by Thomas Broadwood from 1803. By the 1850s, the area surrounding Broadwood’s land was being developed, and in 1862, Thomas Broadwood’s son (also called Thomas) decided to develop their own estate on the land.

After laying sewers in 1862, construction started on the houses and this work would continue until the mid 1870s. Work included the construction of Cornwall Mews which were built to provide stables to the large houses that the mews backed on to, the houses which formed the northern side of Cornwall Gardens.

The name Cornwall Gardens was chosen as the year when construction started (1862) was also the 21st birthday of the Prince of Wales, who also had the title of the Duke of Cornwall (the future King Edward VII).

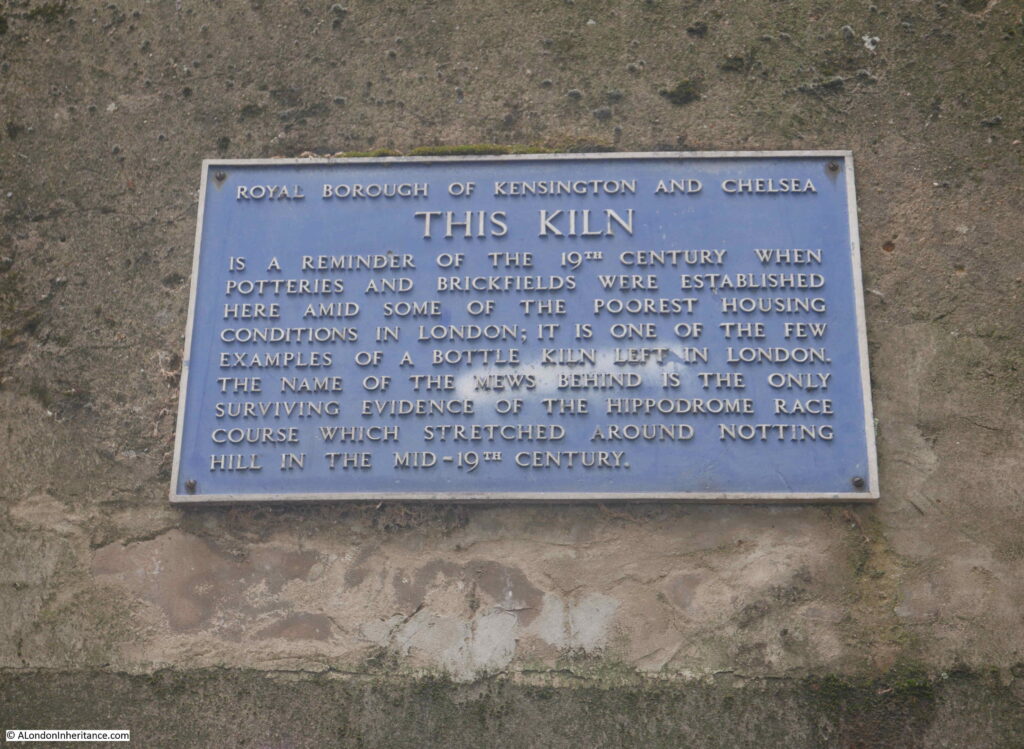

The mews seem to have changed name from Cornwall to Kynance Mews around 1924. Kynance retains the Cornish connection with Kynance Cove on the Lizard, near Helson in Cornwall.

The entrance to Kynance Mews from Gloucester Road, with Kynance Place on the right of the mews entrance is one of the many strange street and building configurations on the estate. Kynance Mews is truncated in length and does not run the full length of Cornwall Gardens. Building lengths vary, and there are some rather odd alignments with the houses of neighbouring streets.

The reason comes down to Thomas Broadwood’s original land holding, with these early boundaries dictating the street and house plans we still see today.

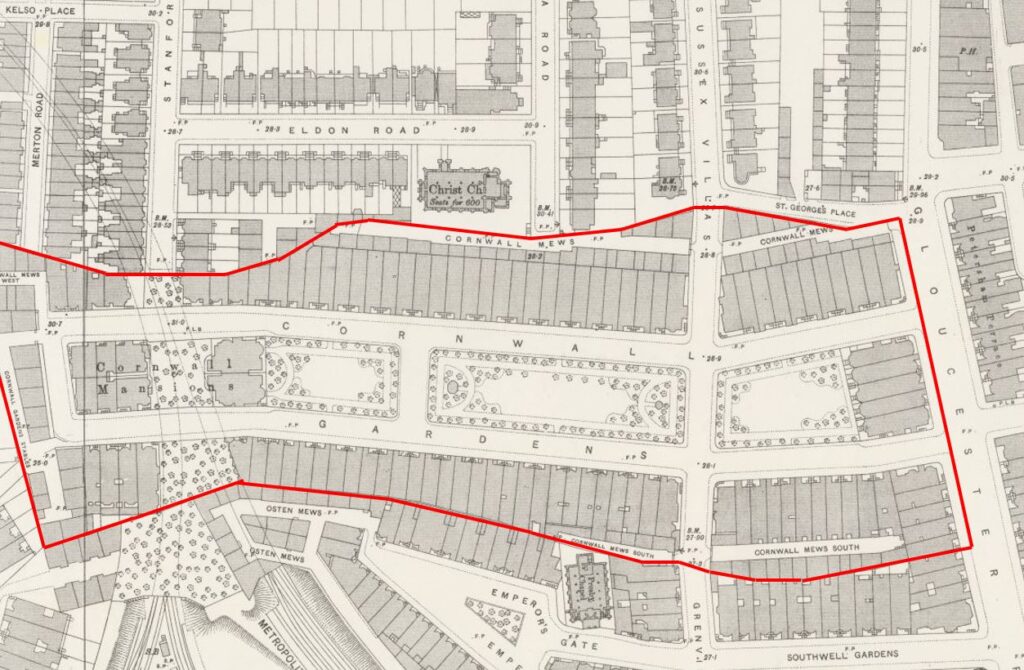

In the following map, I have outlined Thomas Broadwood’s land holding, and the boundaries of the Cornwall Gardens development in red. Cornwall / Kynance Mews runs along the top right of the boundary, but stops short as the end of the mews hit another land boundary, with the length of the houses at this point decreasing to align with the boundary (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’).

The red line of Broadwood’s boundary reveal some very strange street and building configurations. As we walk into Kymamce Mews, one of these can be seen with the first building in the mews that borders Kynance Place (then St Georges Place).

In the following photo the end of the boundary wall is on the right, followed by the first building, which starts of narrow and then does widen out slightly as Kynance Mews and Kynance Place diverge (see the above map).

The first section of Kynance Mews is relatively short, with Launceston Place cutting across (another Cornish connection with the Cornish town of the same name).

At the end of the first section, and start of the second section are two more arches that frame the entrance to Kynance Mews:

All three arches are Grade II listed, with their Historic England listing describing them as “Archway. Circa 1860. Simple stucco arch with rusticated piers and vermiculated architrave, cornice over”.

Crossing Launceston Place, and we can look back at the shorter section of Kynance Mews:

I visited the mews in April, before the plants and trees along the mews had come into leaf or flower. The two arches in Launceston Place should by now be topped with hanging green branches – part of what makes the mews popular with the Instagram and Lifestyle / Travel communities.

Walking through the arch and there is a sign on the right of the arch that points to a Right of Way and some hidden steps that provide a walking route out of the mews.

Walking further along Kynance Mews and we can see the two storey buildings that back onto the houses in Cornwall Gardens. A number of these retain the large doors that once would have been part of the stables.

The census of 1911 provides a view of the employment of those who lived in the mews:

- Groom Domestic

- Caretaker

- Coachman Domestic

- Farrier

- Carman

- Chauffer Domestic

- Horse Keeper

The majority of those living in the mews had jobs that seem to have involved some aspect of providing the transport for those who lived in the large houses in Cornwall Gardens, there were also a number of trades people who were probably employed in local building and maintenance works.

The transition from horse to motor transport can be seen in newspaper reports from the 1910 onwards, including one from the 14th July 1928 when Lady Grace Indja Thomson of Bell Cottage, Kynance Mews was fined 10 shillings for driving without a licence.

Lady Grace Indja Thomson was the wife of Sir Basil Home Thomson, who was typical of many of the residents of the Cornwall Gardens estate, having passed through Eton and Oxford then working in the Colonial Service where he was posted as a Colonial Administrator in Fiji and Tonga. After resigning from the Colonial Service and returning home, he took up appointments first with the Prison Service, then the Metropolitan Police.

I suspect that the original occupiers would have been stunned by the prices the houses in Kynance Mews now sell for, and the rate at which they are increasing. A typical terrace house in the mews sold for £975,000 in 2001 and was sold again in 2020 for £2,175,000.

Despite these prices, and being in a mews, the houses still suffer with road works. This is the reason why my 2021 photo is slightly different to my father’s, which, as far I could work out, was taken in the middle of the road works.

The western end of Kynance Mews terminates in a dead end, with houses on another estate, not part of Thomas Broadwood’s original land holding and Cornwall Gardens development on the other side of the wall.

There are some rather ornate chimneys lining the roofs of some of the houses in Kynance Mews:

To the north of Keynance Mews, on the other side of the boundary wall is Christ Church, Kensington:

In my father’s 1986 photo, there is a sign projecting from the wall on the left. The sign directs the walker to a set of stairs leading up to Victoria Road, on the eastern boundary of the church. The stairs form part of the pedestrian right of way seen on the sign on the arch leading to this section of the mews.

There are a number of stubs of roads in this part of Kensington which reflect the original estate boundaries. Victoria Road has a short stub that passes the church and ends at the boundary wall with Kynance Mews, and this stub of road provides access to the stairs which can just be seen behind the motorbike and adjacent to the lamp post.

The above photo also helps to demonstrate the difference between the size of the mews houses in the foreground, and the much larger houses to the rear which faced onto Cornwall Gardens, and that the mews buildings were built to serve.

For the rest of the post, I will take a walk in the streets to the north of Kynance Mews, as the stairs were part of the original 1986 photo and the mews and land to the north show how original owners and land boundaries influenced the current layout of streets and buildings in this part of Kensington.

The land to the north of Kynance Mews was known as the Vallotton estate, as it was developed by the Vallotton family.

John James Vallotton purchased the first parcel of land in the area in 1794. His son Howell Leny Vallotton continued with land purchases to form a significant block of land amounting to around 20 acres.

Development of Victoria Road seems to have started around 1829, and development of the area would continue through the 1830s to 1850s.

The Vallotton estate has a varied mix of architectural styles and construction materials. On the corner of Eldon Road and Victoria Road is number 52 Victoria Road:

Built between 1851 and 1853 for the painter Alfred Hitchen Corbould, the building has a square blue plaque recording his residence here, and that he was Art Tutor to the children of Queen Victoria.

Opposite the above house, and on the corner of Eldon and Victoria Street is Christ Church Kensington, the church that backs onto Kynance Mews.

The church was built to a design by Benjamin Ferrey between 1850 and 1851 to serve the growing population of Vallotton’s estate. Vallotton had donated the land, and subscriptions were raised to fund the £3,540 bid for the work from builder George Myers of Lambeth.

Very few changes have been made to the church in the 170 years since completion and the church still looks as it was designed and completed.

Christ Church Kensington also serves the Cornwall Gardens estate, and is possibly one of the reasons why there is a public right of way between Kynance Mews and Victoria Road, to provide easy walking access to the church from the mews and Cornwall Gardens.

A church had been planned on the western end of Cornwall Gardens, however whilst the estate was being developed, the Metropolitan and District Railway was also being built and used land through the western end of the gardens where the church had intended to be placed.

The railway used the cut and cover method of construction and therefore prevented any work on the western end of the estate whilst it was being built, and complicated any construction on the land above when the railway was completed.

From the church, I continued to walk north along Victoria Road, the street that was the first part of the development of the Vallotton estate.

Victoria Road originally consisted of semi-detached pairs of villas, surrounded by substantial gardens. There has been a fair amount of ongoing development of the houses resulting in few being exactly as built.

Despite changes since their original construction, the houses still look magnificent. The street is quiet as the design of the estate and boundaries with other estates mean that it is not a through road.

The flowers and spring blossom on the trees add to the photogenic appearance of the estate.

Victoria Road is a long street that runs all the way north to Kensington Road, and I do not intend to walk that far, rather head back to the start of Kynance Mews, so at the road junction with St Albans Grove, I turn right.

It is here that I cross into another of the original estates that developed this part of Kensington.

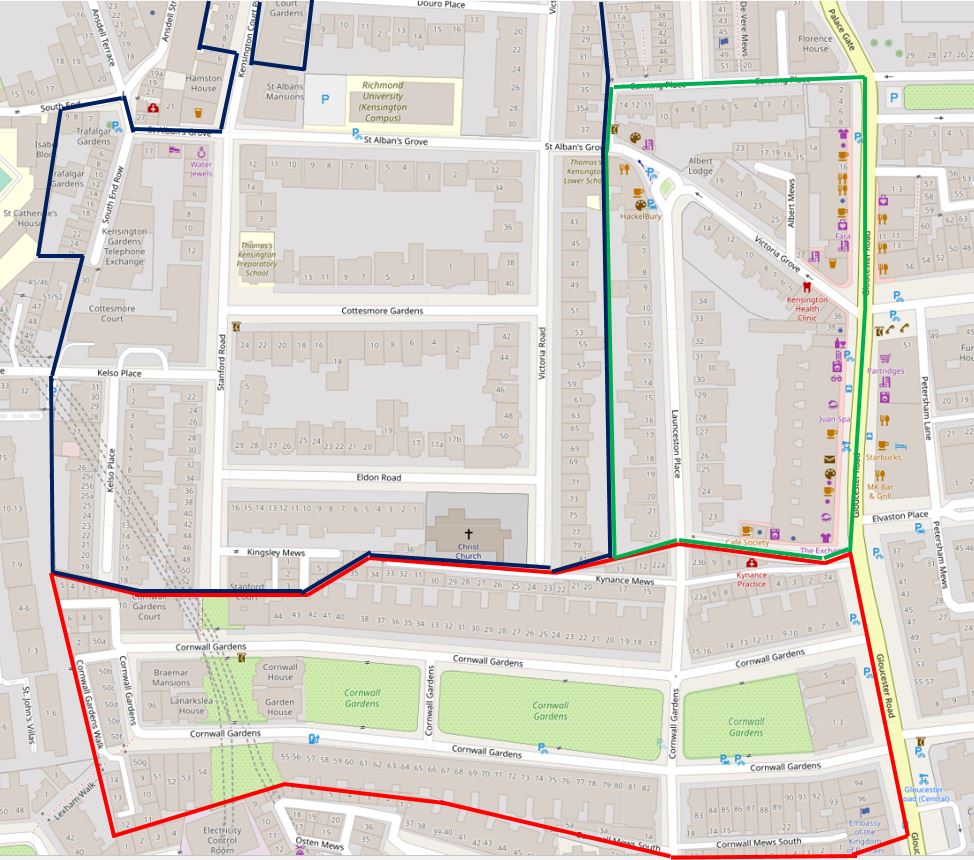

In the following map, I have marked the three estates that I am walking through. The Cornwall Gardens estate is marked by the red line. The Vallotton estate is bounded by the dark blue line and can be seen as the larger of the estates as it continues to head north.

At St Albans Grove, I am turning into the third estate, the boundary marked by the green line of the Inderwick Estate (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

The land comprising the Inderwick estate was purchased by John Inderwick in 1836 from Samuel Hutchins, who in turn had purchased the land from the manor of Kensington.

John Inderwick was an importer of pipes and snuff boxes who lived in Wardour Street. His pipe business was still in operation until as recently as 2000 when the business was finally closed. It had operated in Carnaby Street since the 1960s.

The relatively small size of the Inderwick estate probably explains the speed of construction, with work starting in 1837 and completed by 1846, with Launceston Place being the last street to be developed.

In the above map you can also see where the railway cut through the western end of Cornwall Gardens using the cut and cover method of construction. This was where the Cornwall Gardens church was intended to be built.

Launceston Place was the street that took me back down to Kynance Mews. The houses in Launceston Place are slightly smaller than Victoria Road, but are still lovely semi-detached villas.

With some interesting designs at some of the end of terrace pairs:

Where the gardens at the rear of the houses in Launceston Place meet the gardens at the rear of the houses in Victoria Road, there was an old footpath before the estates were built, that went by the name of Love Lane, which would also have been the original boundary of the Vallotton and Inderwick estates.

I find it fascinating when walking London’s streets that the route of 500 year old footpaths, and ancient land holdings can still be traced today.

Until 1883, Launceston Place was called Sussex Place. the name change seems to have been to extend the Cornish connection across the area.

Before Launceston Place cuts across Kynance Mews, I turn into Kynance Place, a short street that to the south has the narrow buildings and brick dividing wall with Kynance Mews, maintaining the division between the Inderwick and Cornwall Gardens estates.

The northern side of Kynance Place has a line of small shops:

The early history of Kynance Place illustrates the problems that the early developers of these estates had with infrastructure.

Whilst Inderwick could complete the sewers across his estate, he would have needed a larger sewer to connect with to drain away from the estate. When he started to build the estate, no such sewers were available. There were plans to build a large sewer along Gloucester Road, however Inderwick would have had to pay the full costs of such a project.

Until there was a connecting sewer available, Inderwick was forced to construct a large open cesspool where Kynance Place now stands. Although Inderwick improved his own infrastructure, the estate had to wait until the 1860s when the Gloucester Road sewer was finally completed.

And at the end of Kynance Place, I am back to where I started the walk through Kynance Mews.

Kynance Mews probably looks even better now as the greenery will probably be out, and it is well worth a visit for a fascinating walk through an area where the boundaries of the three original estates that formed the area can still be found.