This year, the BBC is celebrating 100 years of broadcasting, having started in 1922 with a limited programme of music, drama and talks. There is another BBC anniversary this year, as it is 90 years since Broadcasting House on Langham Street / Portland Place opened as the first building in the country, purpose built for the new medium of broadcasting.

I have a copy of the book the BBC published in 1932 to celebrate the opening of the new building, so I thought I would take a look at the building and some of the many photos from the original book, which show leading edge broadcasting design and technology from 1932.

Walk north along Regent Street from Oxford Circus, into Langham Place, and this is the first view of Broadcasting House, just behind the distinctive tower and spire of All Souls:

When the BBC first started broadcasting, the BBC’s premises were at Savoy Hill, however with the rapidly growing popularity of broadcasting along with equally fast technical development, it was soon clear that a new building was needed, ideally a building custom designed for broadcasting.

The site of Broadcasting House was initially to be developed as what were described as “high-class residential flats”, however the location was perfect for the BBC. It offered a central London location, close to multiple transport links, and with just enough space to construct a new building.

The owners of the site agreed to build the BBC’s new centre and offered a long lease, however the BBC purchased the site before the building opened.

The site was of some size, but was strangely shaped, with a long curved section along Portland Place. The building was limited in height as there were a couple of nearby buildings that had their right to light protected under the custom of “ancient lights”.

The architect of the building was Lieut-Col G. Val-Myer FRIBA, who was supported by the BBC’s Civil Engineer, M.T. Tutsbery.

Broadcasting and the functions of the BBC dictated some challenging requirements. Despite being called Broadcasting House, the building would house a considerable number of people working on the administrative functions of the BBC. These would all require naturally lit space.

A wide range of studios were also needed, of very different size and function, from small studios for one or two people, up to concert hall size. These studios needed to be sound proofed both from the noise of the street, and internally generated noise.

A creative design solution met these competing requirements. Broadcasting House was constructed as a building within a building. A central core was constructed of brick, avoiding as much as possible the use of steel girders and stanchions which would have transmitted sound. The studios were located within this central core, and they were separated where possible by quiet rooms such as the library.

The outer core of the building housed office space, so these rooms had natural light and acted as an additional level of sound proofing between street and studios, with the inner brick core providing internal sound proofing.

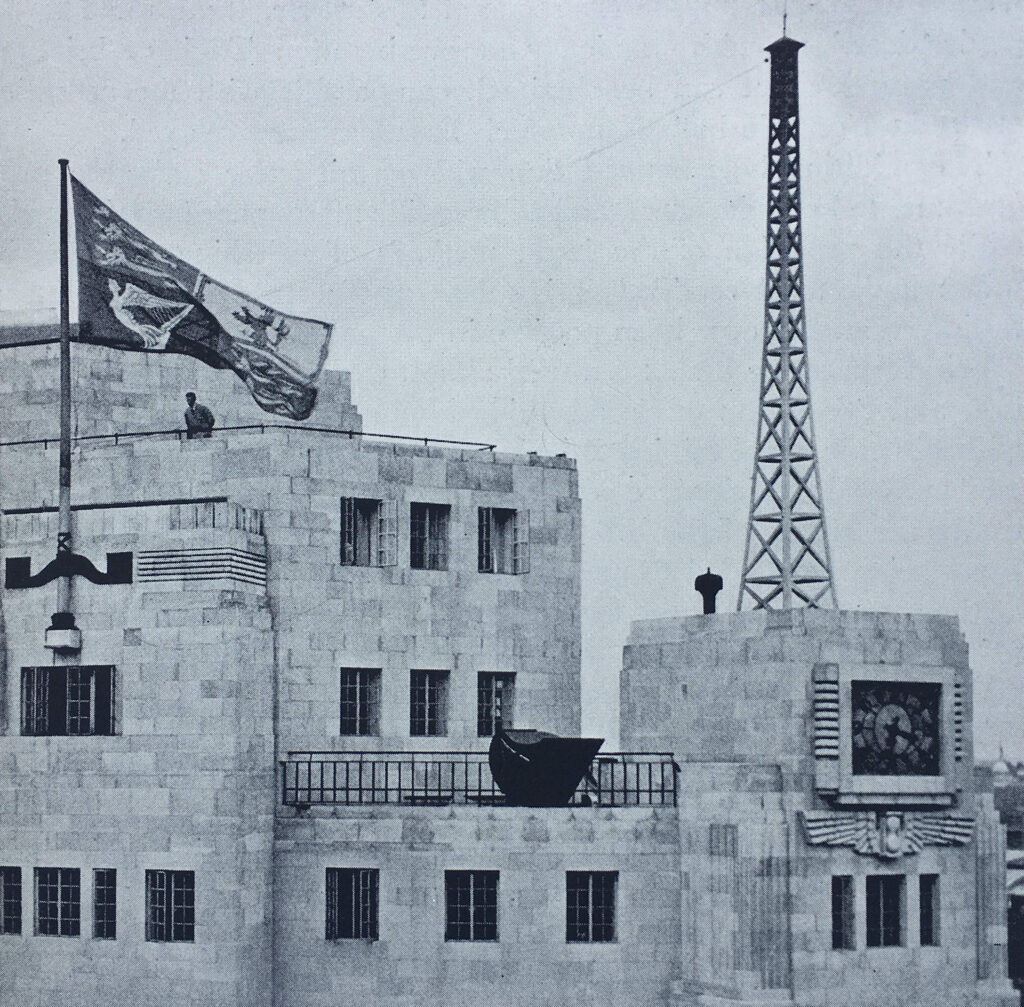

The external design of the building had some distinctive features. Looking above the main entrance, and one of the aerial masts stands above a clock:

The main entrance at bottom left:

Eric Gill was responsible for the sculpture decorating the building. The BBC requested that the works would feature Shakespeare’s Ariel as the BBC considered this would represent the “invisible spirit of the air, the personification of broadcasting”.

The sculpture above the entrance shows Prospero, Ariel’s master, sending him out into the world. Gill created the work in situ during the winter of 1931 / 1932. Before being uncovered and revealed to the public, the Governors of the BBC inspected the work and considered that, Ariel’s “appendage” was too large for public decency and a reduction of a couple of inches was made.

Eric Gill was also responsible for some of the sculpture on 55 Broadway – London Underground’s Head Office.

To the right of the above photo is the considerable extension that has been added to the original Broadcasting House.

Walking along Portland Place, and we see the curved façade of the buildings, with the rows of windows providing natural light to the offices behind:

To the lower right of the above photo is Eric Gill’s “Ariel hearing Celestial Music”:

Much of the building is faced with plain stone, with identical, regularly space windows, however there are some key features along the centre of the façade:

At the top are the Coat of Arms of the BBC. The circle in the centre represents the world, to show the breadth of the BBC’s coverage. Running along the bottom of the sculpture is the BBC’s motto “Nation shall speak peace unto nation”:

Below the arms is a long balcony decorated with birds of the air:

And below the balcony are “wave” symbols:

On the northern end of the façade is another work by Eric Gill, representing Ariel between Wisdom and Gaiety:

Looking back towards Langham Place with Broadcasting House on the left:

A large extension has been added to Broadcasting House. This was done to help consolidate many of the different BBC London activities into a single building, with the move of BBC World Service from Bush House into the new extension, along with many of the functions that were in Television Centre such as News, when the BBC left Television Centre.

Looking to the east of Broadcasting House, and we can see the original building to the left, with the new building to the right and at the far end:

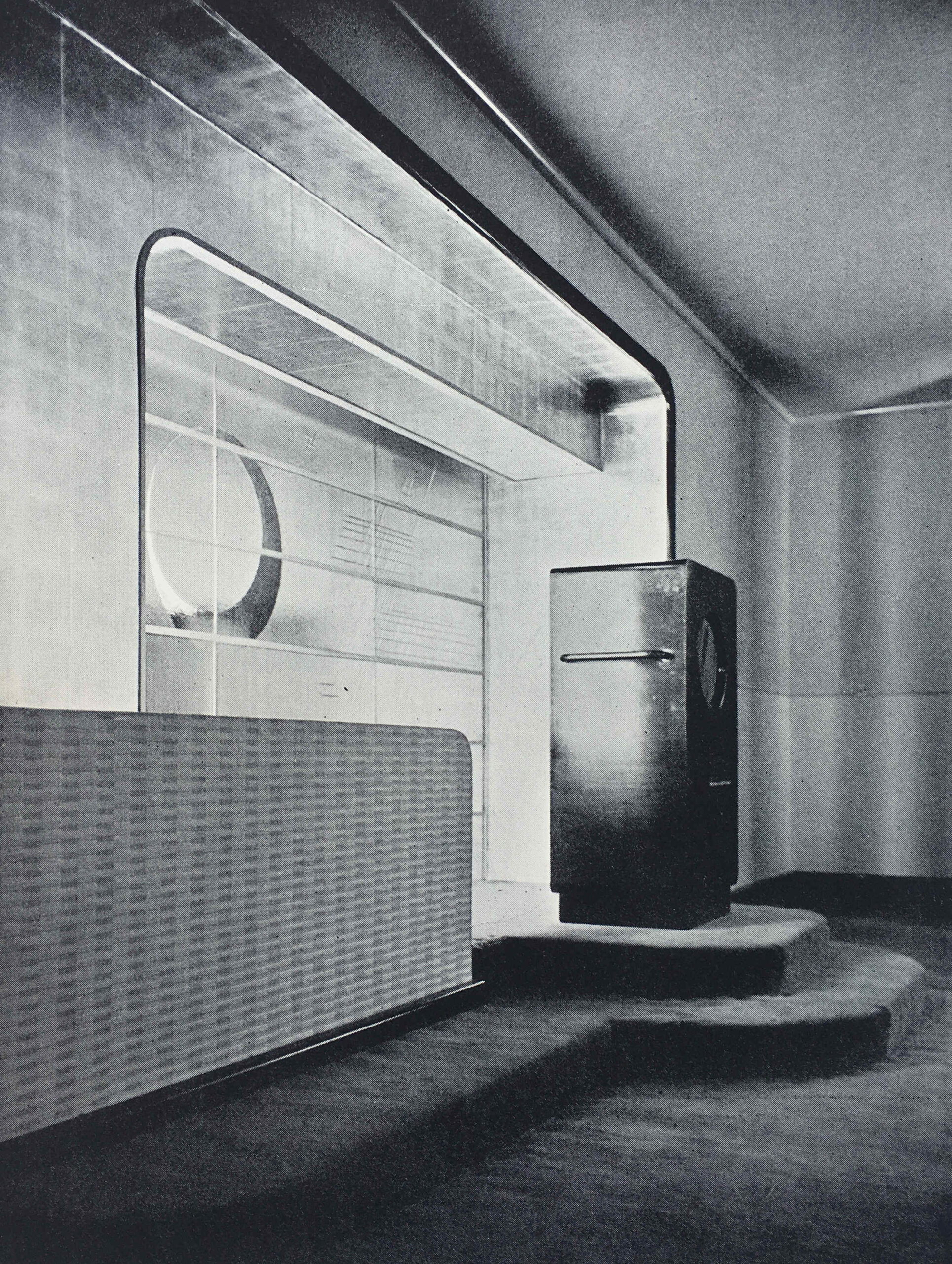

The BBC’s 1932 book celebrating the opening of the building is full of photos of the new building, internally and externally, and shows what was considered leading edge design for the new medium of broadcasting in 1932.

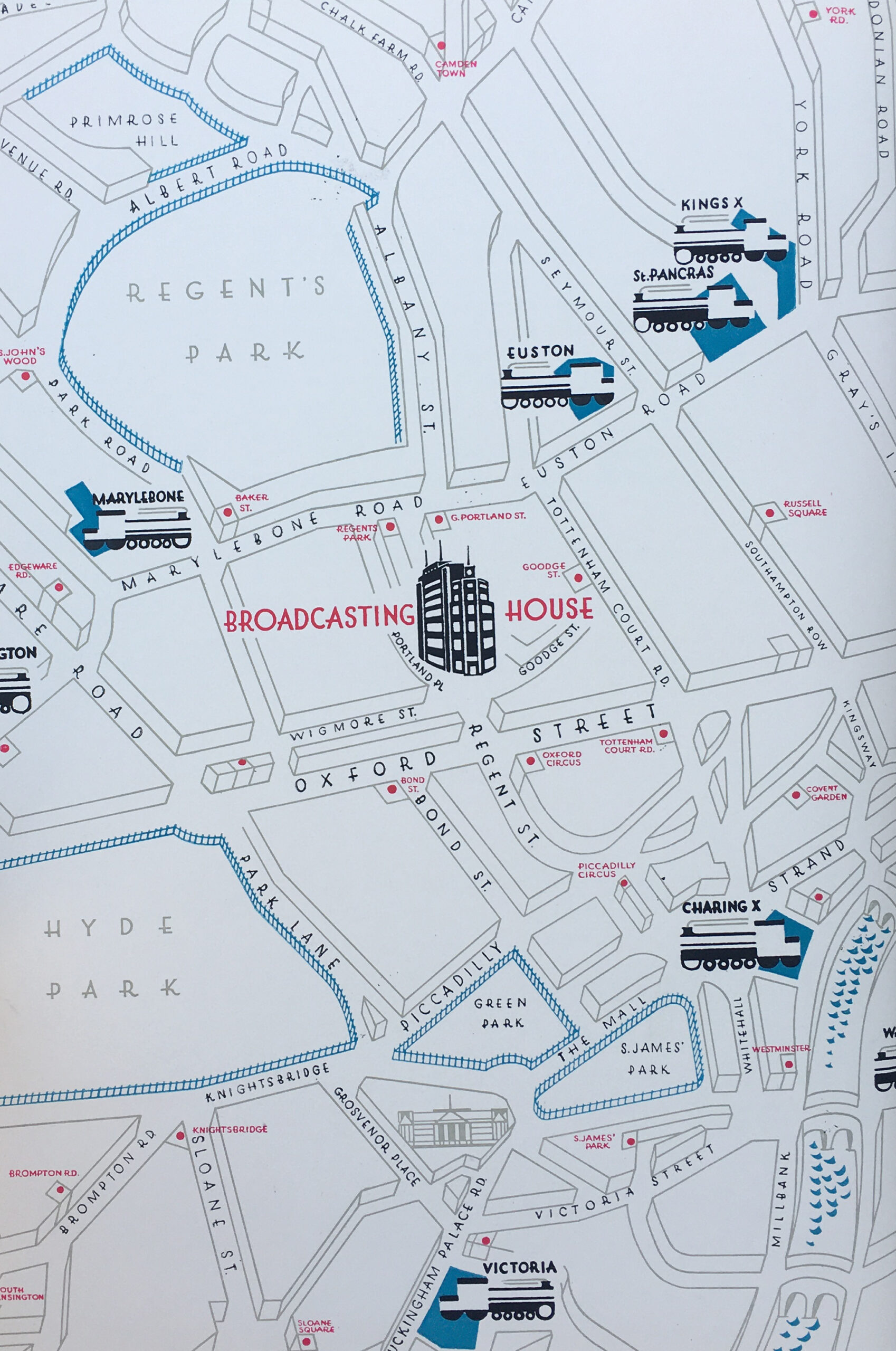

At the start of the book is a map showing the location of Broadcasting House, with an emphasis on the closeness of the building to a range of travel options. This was important not just for those who worked full time in the building, but for the many people who would visit the building for a short time to participate in one of the many concerts, talks and plays that were broadcast.

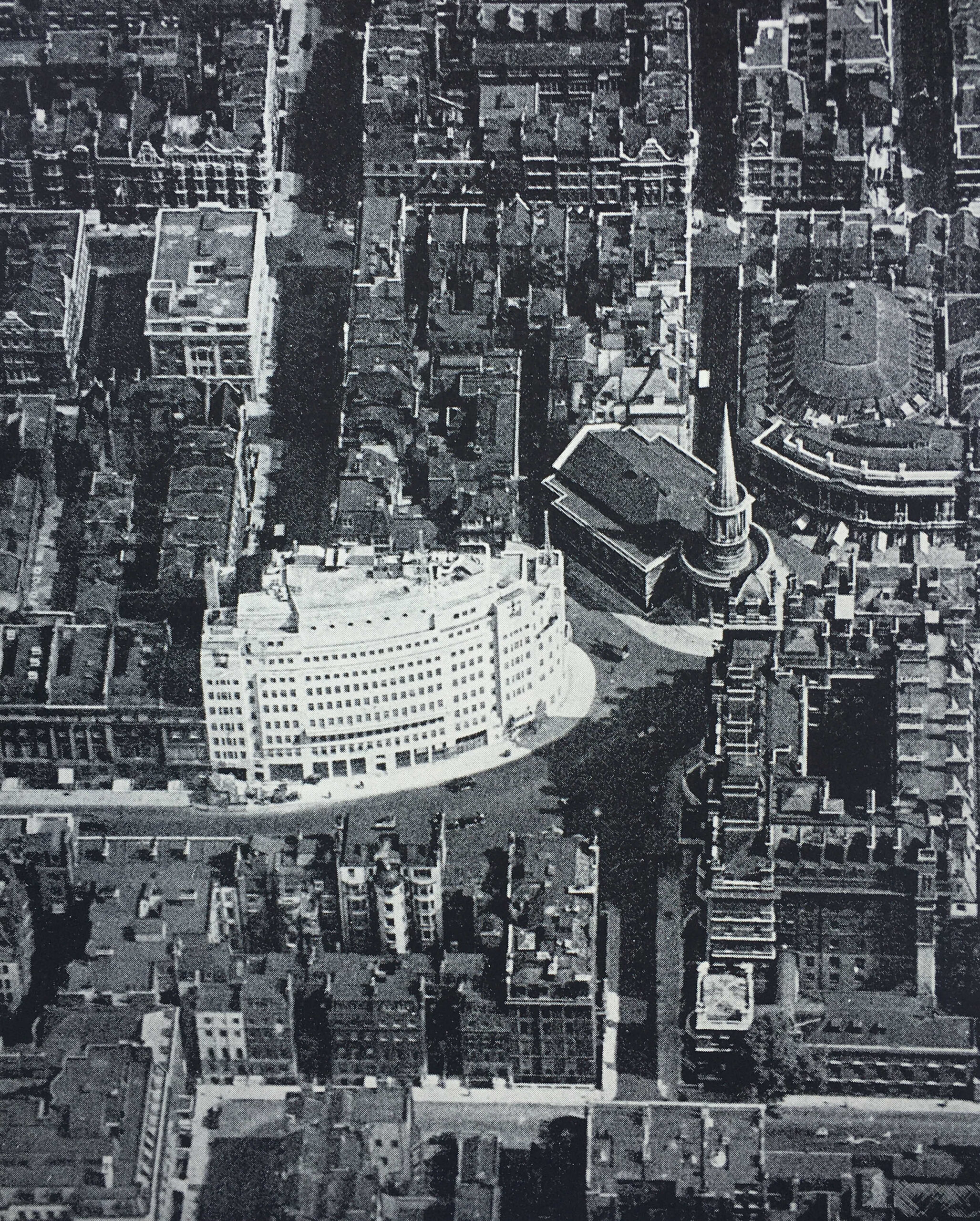

An aerial photo shows Broadcasting House, just completed, and gleaming white among the surrounding dirty buildings of the city:

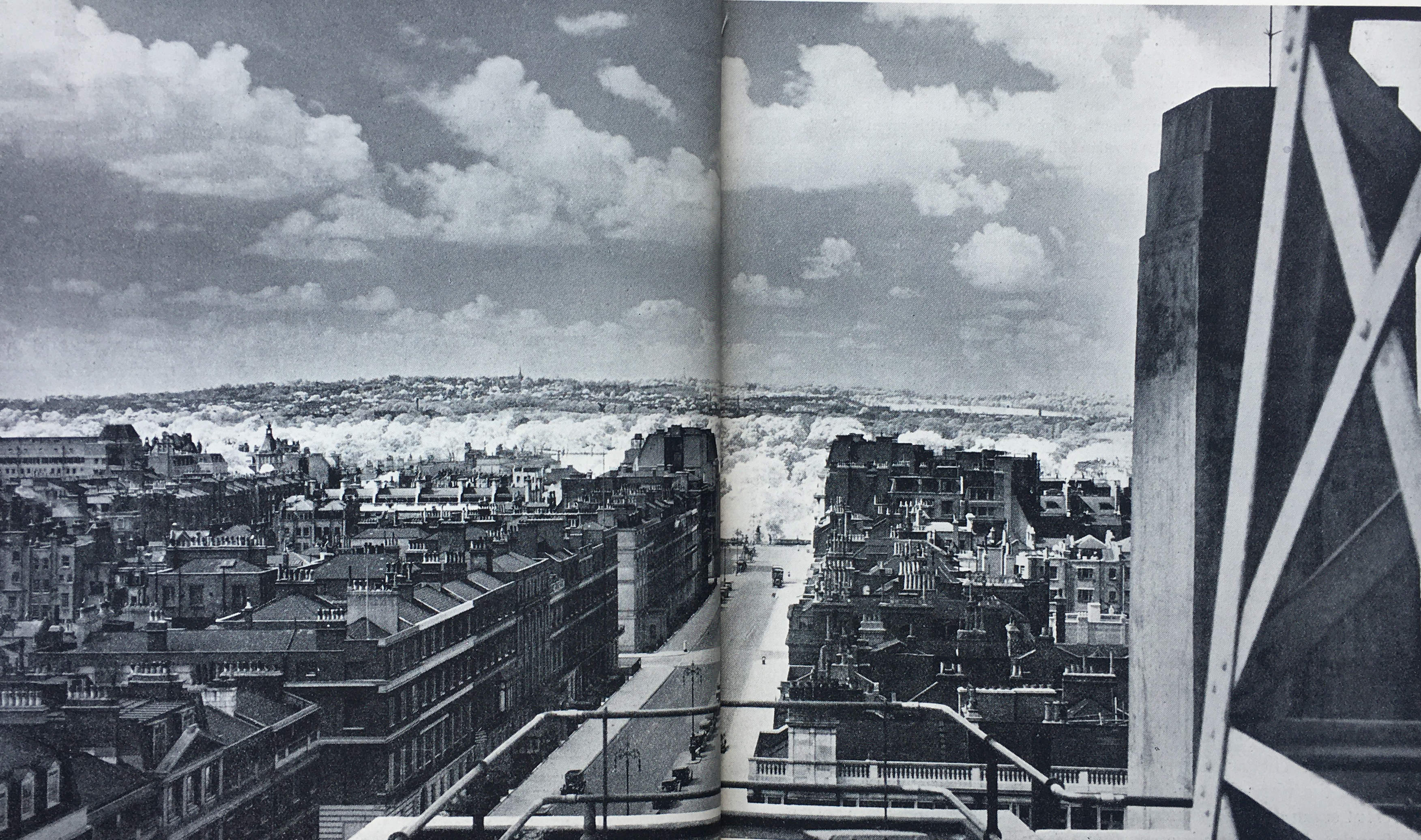

The book includes a rather unusual photo, looking north from the roof towards Hampstead. The photo was taken using an infra-red camera, which at the time improved the level of detail at a distance, and had the effect of showing green objects such as trees as dazzling-white:

The clock and mast which are still visible today. On the balcony, to the left of the clock is a loud speaker which was used to broadcast the sound of Big Ben, imitating the natural strength of the bell.

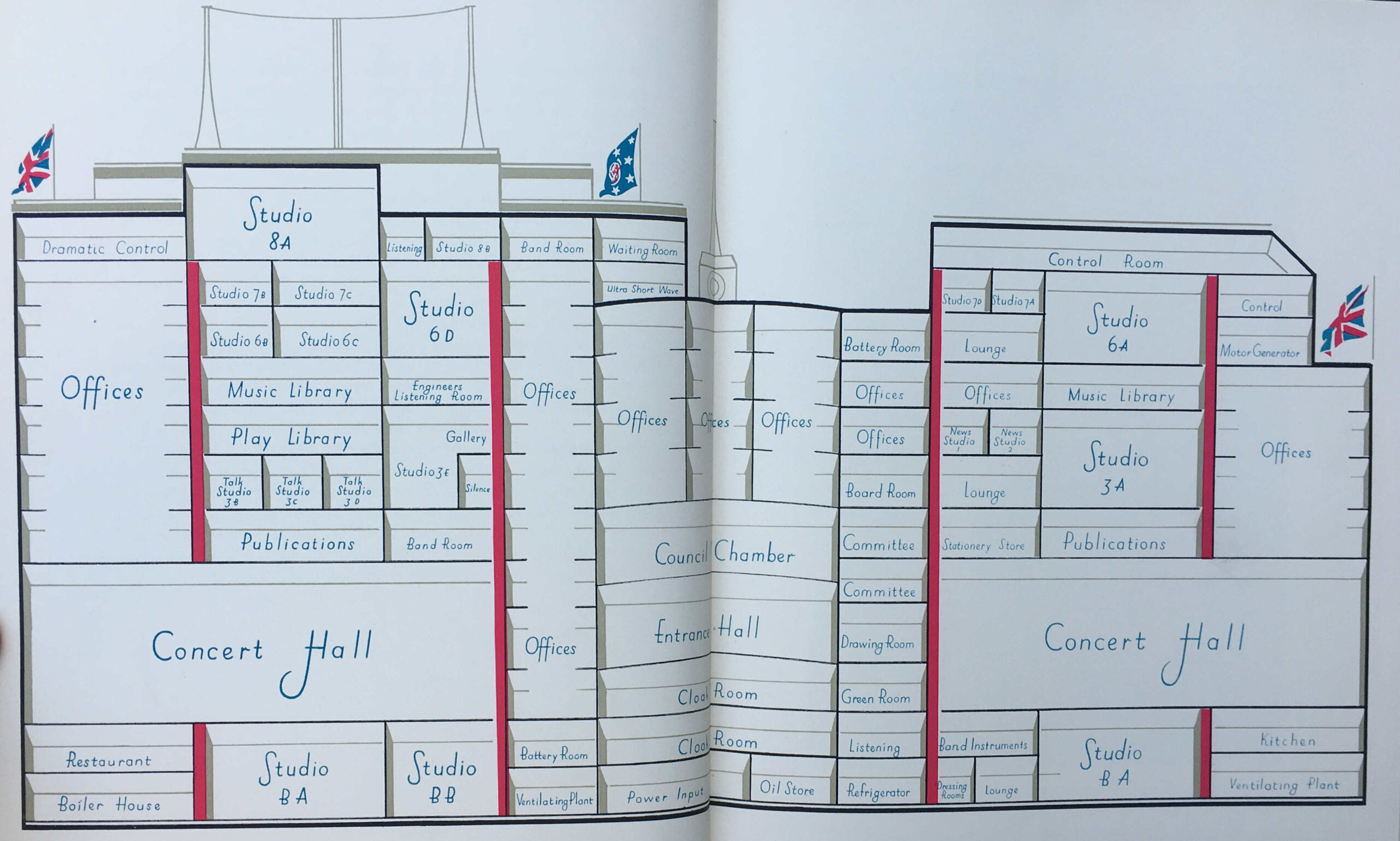

The following diagram shows the internal core of the building with the outer offices removed. The diagram shows how much had been crammed into the space available, as well as the positioning of quiet rooms between the studios:

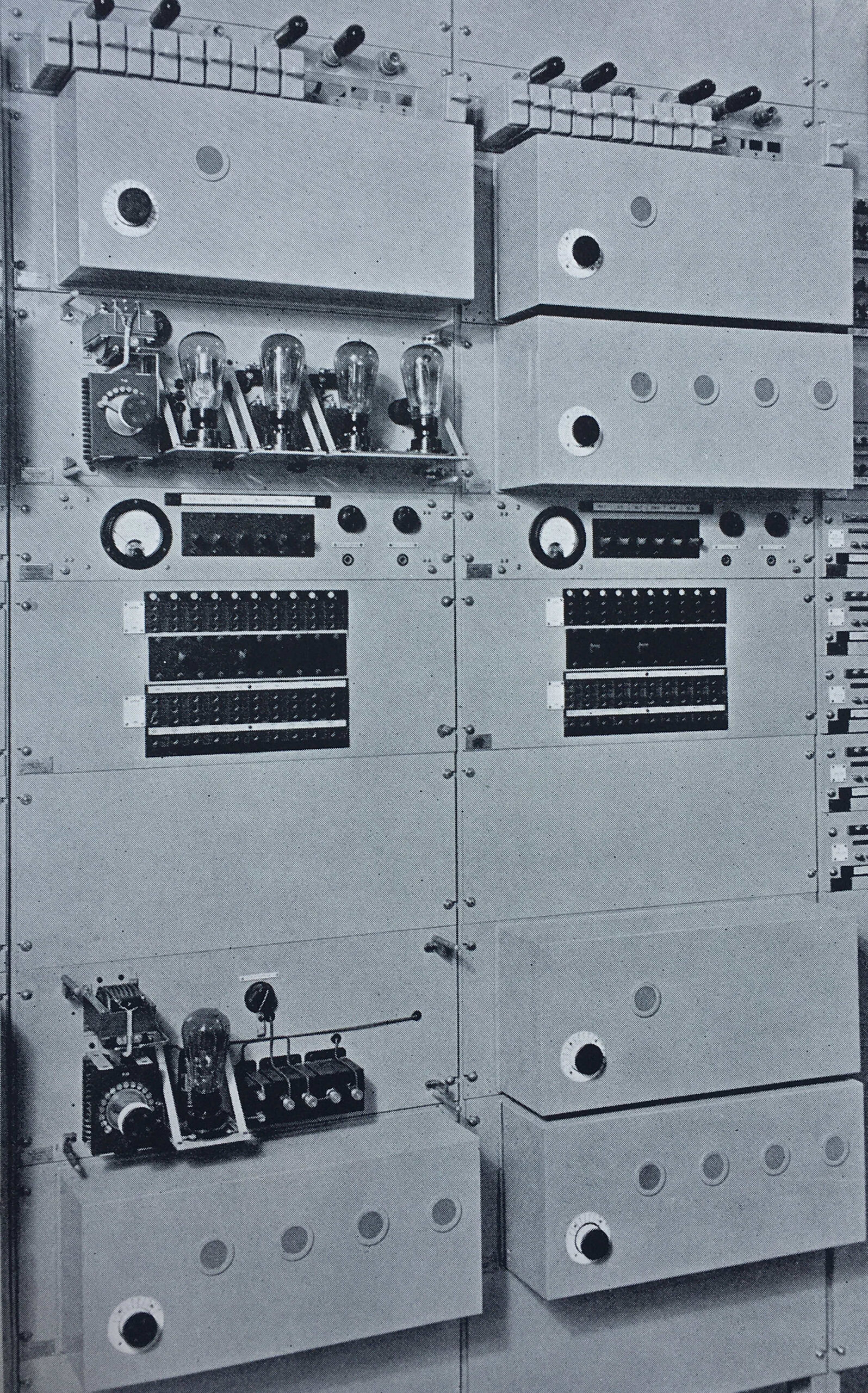

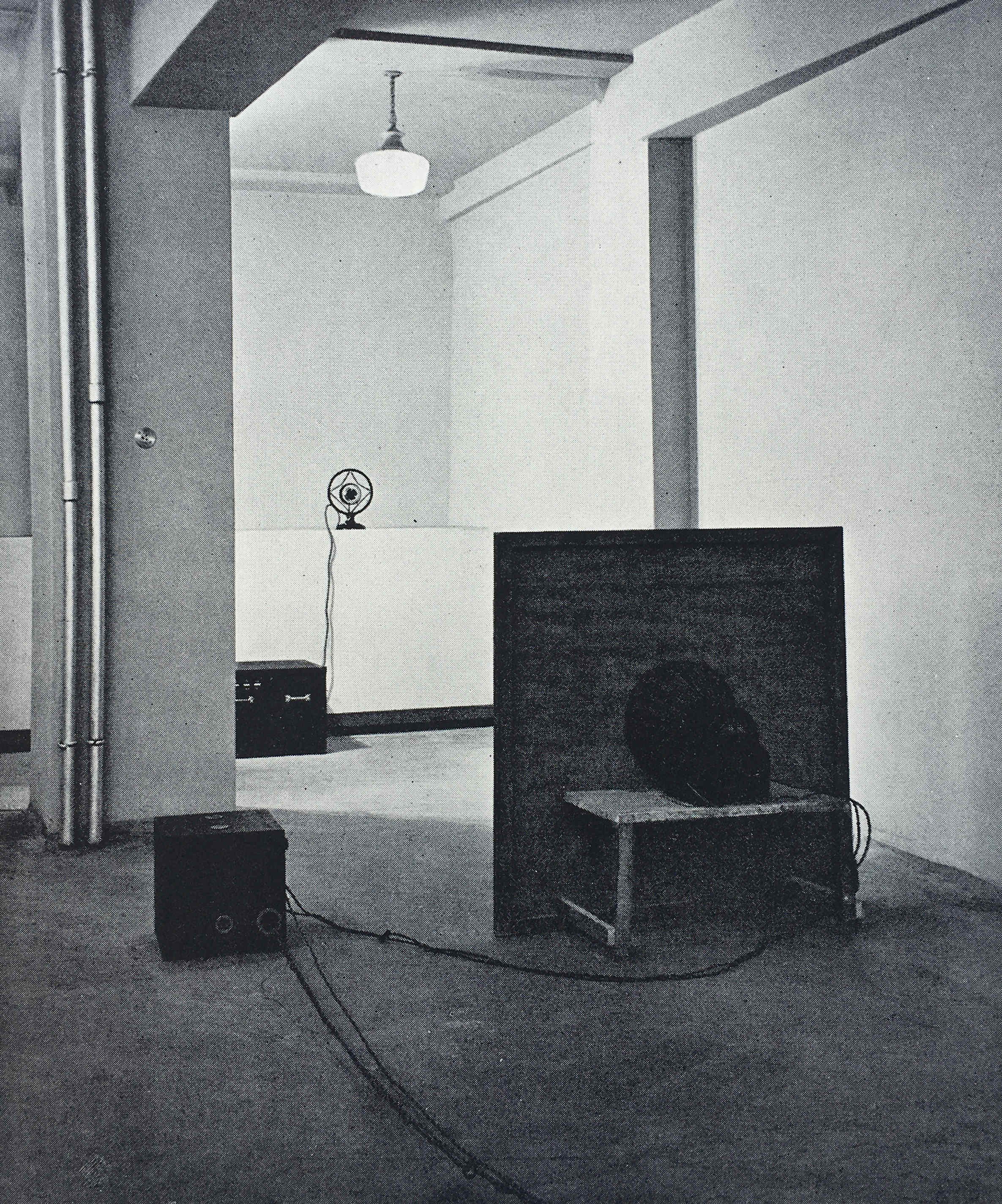

The book covered all aspects of the new building, including the technical infrastructure that enabled broadcasting. The following photo is the Control Room and apparatus is described as being “battleship grey with stainless steel fittings”:

Two of the amplifier bays, one with a cover removed showing the valves that were critical to this type of equipment, long before transistors had been invented:

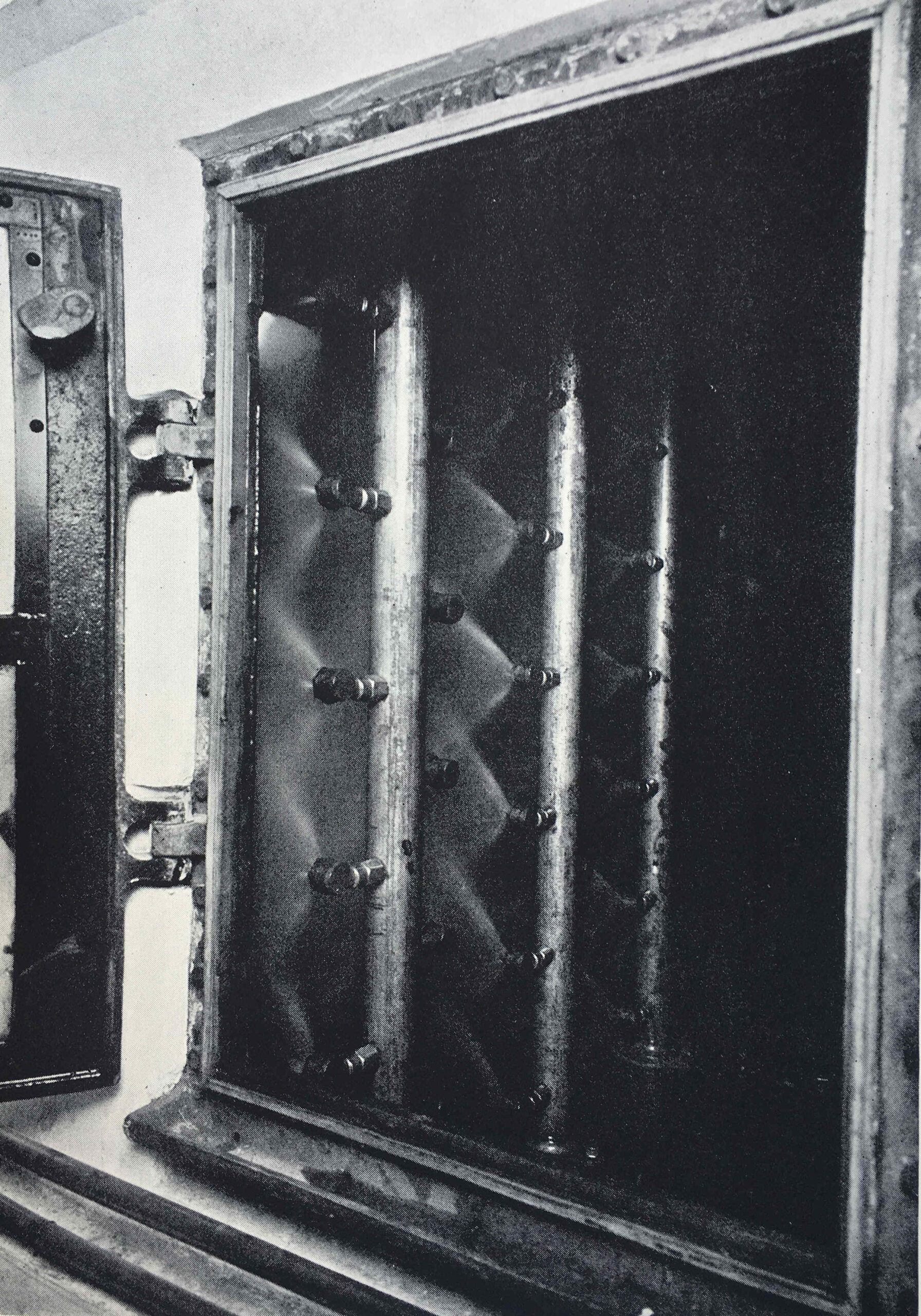

One of the issues with being in London was the polluted air with still plenty of smoke in the atmosphere. Broadcasting House featured state of the art air conditioning equipment, which included outside air being passed through a spray of water to remove particles in the air, as shown in the following photo:

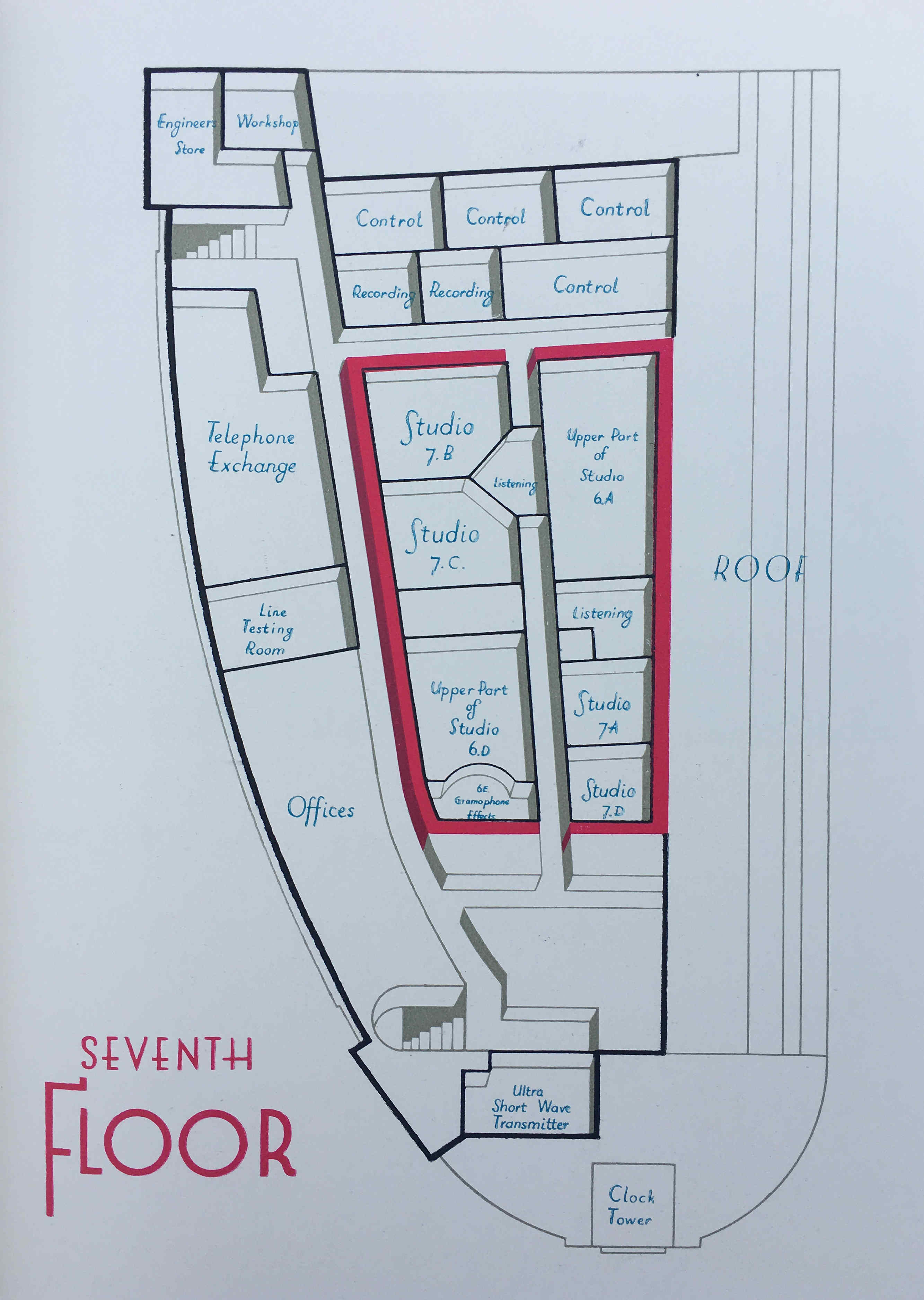

The book also includes plans of each floor, the following plan of the seventh floor being an example, with the studios located in the central core:

The BBC provided tours for journalists in May 1932, and papers of the time were full of glowing articles about the new building. The following is from the London Correspondent of the Dundee Courier, who wrote an article titled “The Palace of Broadcast – A peep into new home of the BBC”:

“When the British Broadcasting Corporation decided to build themselves a new home they did the job thoroughly.

After a tour of Broadcasting House in Portland Place my mind was in a whirl of gigantic boilers, pictures of the most modern studios, miles of corridors, hundreds of lights, and a thousand and one other things.

The tour reflected the BBC’s thoroughness and started in the basement, which is three floors below street level, and finished eight floors above.

The people who matter in broadcasting said ‘we must have no noise from the outside in our studios’ therefore, each studio, which has no communication with the outside world apart from the door, has its own exclusive current of air for ventilation and heat so that no sound is carried through from one room to another.

The experts have taken sound well in hand, and controlled its unruly antics. The studio for ‘talks’ has been made so dead that there are no reverberations at all. If you speak in the studio your voice sounds like a voice heard in a dream. It is most eerie.

The furnishing is definitely 1932, and about this studio for discussions there is a make-yourself-at-home atmosphere.

Soft beige carpets cover the floors. The walls and the ceilings are delicate shades of beige, with a touch of orange and cream stripes around the walls. Below a mirror which stretches across one side of the room there is a jade green vase containing huge flowers.

The chapel studio is of great beauty. The cream walls are lit by pillars of light. Two tall columns painted green reach the ceiling, which is of blue with silver stars and signs of the Zodiac.

Next to each studio, of which there are 22, there is a little listening room. There is a window through which the performers can be seen. Here an announcer can make announcements without the artists being able to hear him, and he can check the quality of the transmissions.

The ‘effects’ room is above. here it is all very scientific. In the centre is a large table that swivels round. It is divided into sections, each of which is covered in a different substance to give different sounds when it is rapped or hard objects dropped upon it.

The equipment of this room also includes a pall full of lumps of bricks and a tank of water, and to mention a humble sheet of iron for thunder.

Then there are a series of records for crowd noises, angry, and jolly, English or foreign. Others give cries of babies and every form of animal.

All those cheery messages about depressions of Iceland and anticyclones together with news, emanate from a very chic little studio of which the walls are matted silver. Light is thrown upon the subject from a large globe at the end of a long telescope-like stand.

Such is the ‘Radio Village’. There are dressing rooms, waiting rooms, artists’ foyers, refreshment lounge, libraries and, to complete it all, a small black cat who wanders about at will, and not at all impressed with the dignity of the surroundings.”

Photos from the book show the “make-yourself-at-home atmosphere” described in the article, for example Studio 8B used for Debates and Discussions:

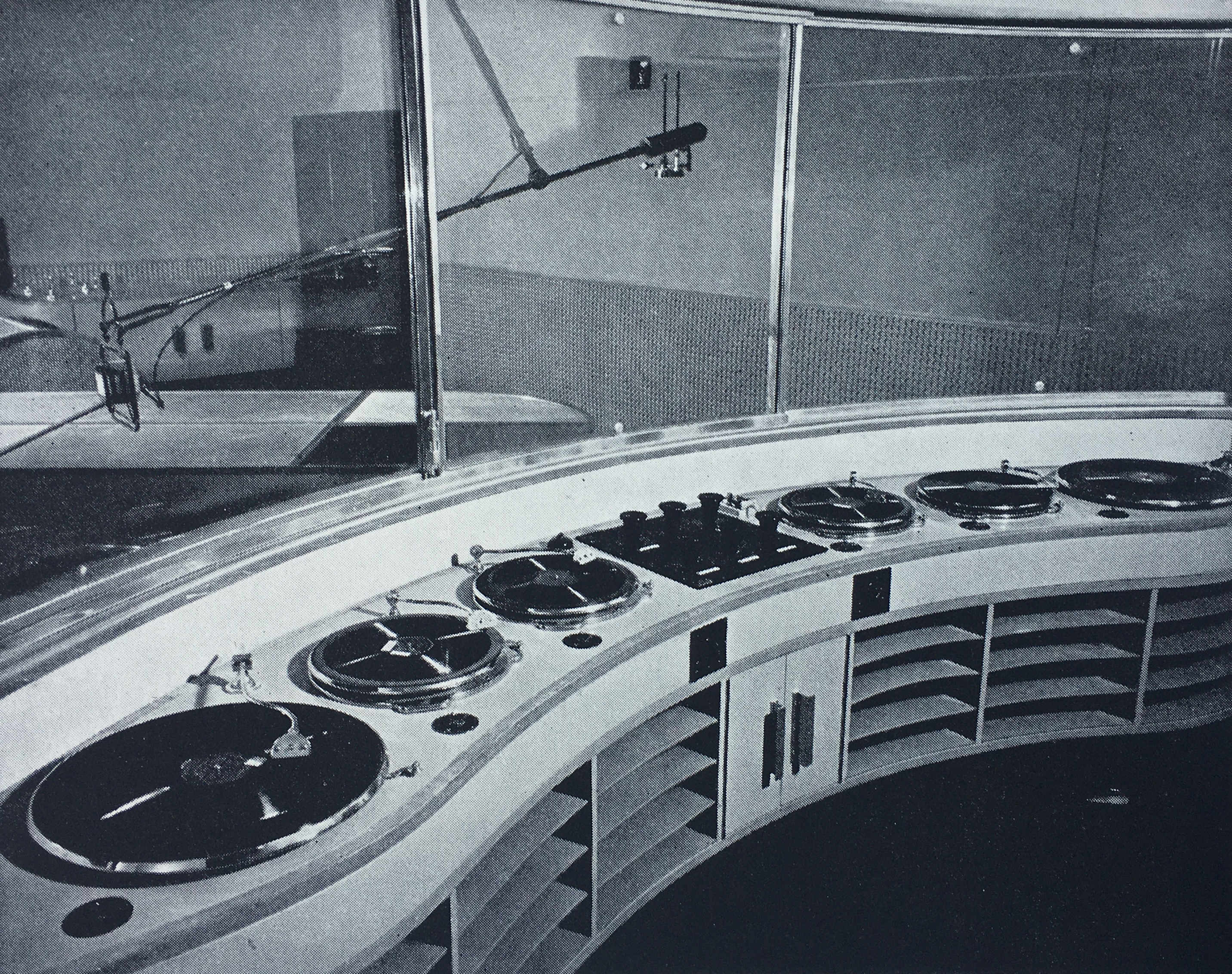

Studio 6E – Gramophone Effects, with plenty of turn-tables to play records of effects:

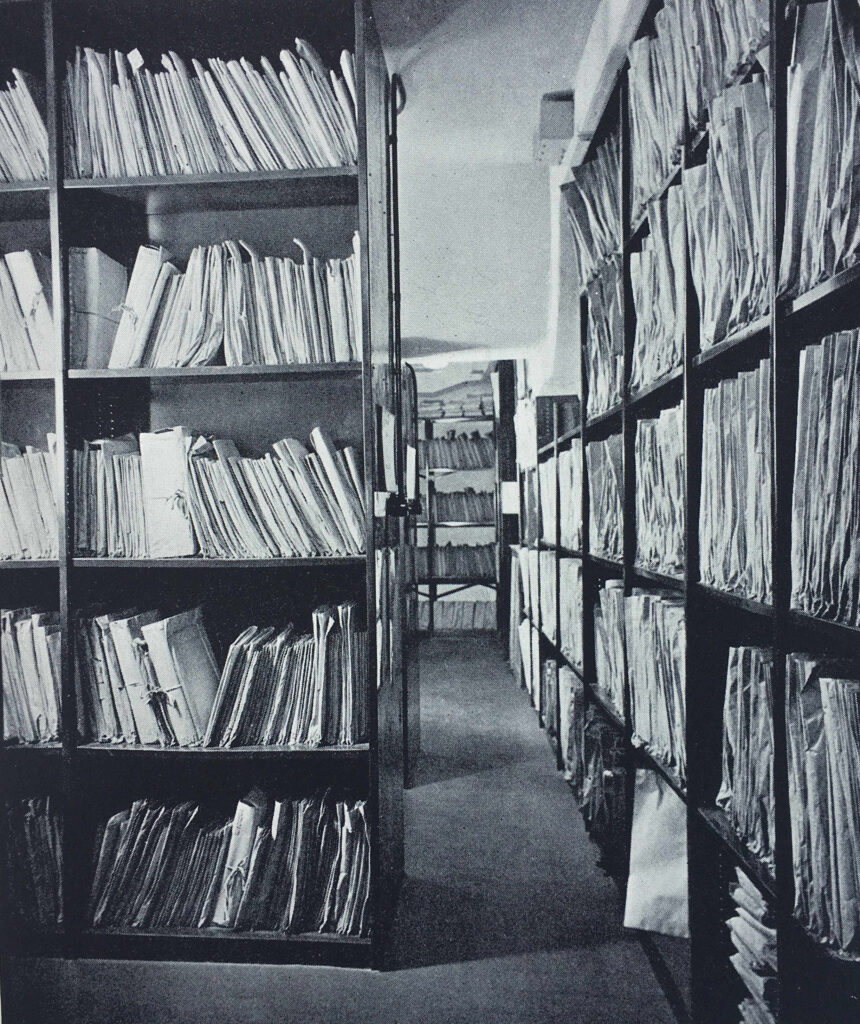

The Music Library, which the book claimed to be the largest in the world, with every kind of music from manuscript parts of Bach cantatas to the latest comic songs:

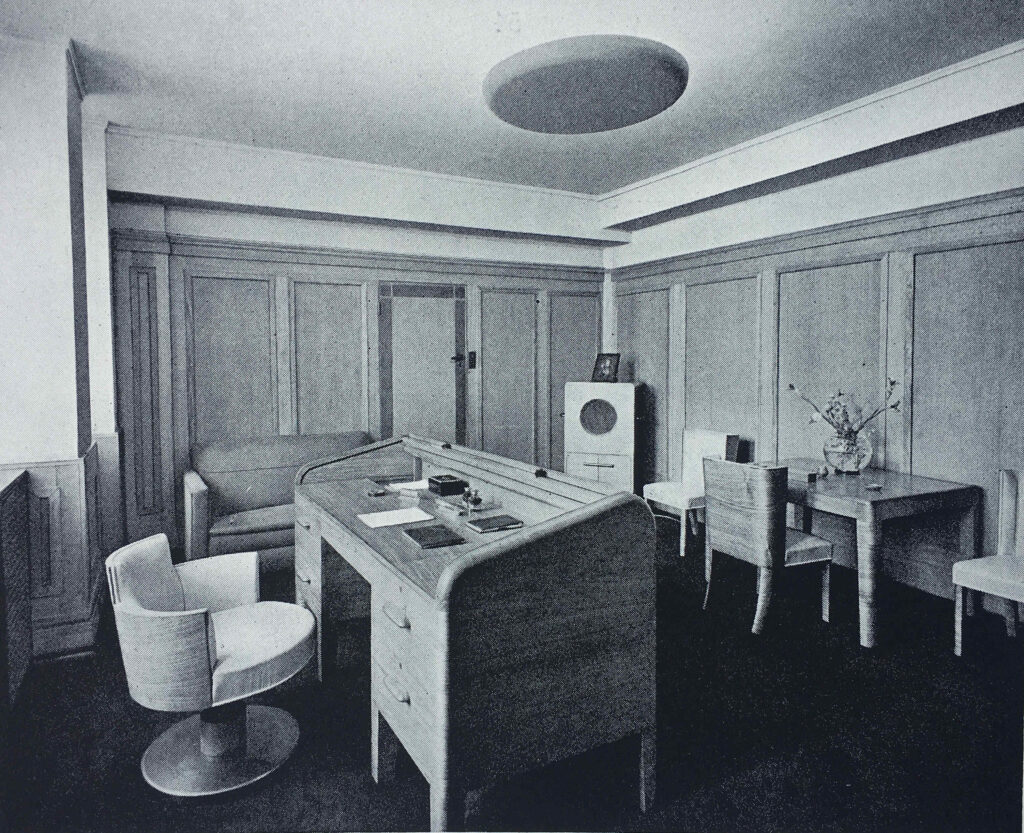

The Office of the Director of Programmes:

One of the interesting aspects of studio design in the early 1930s is that the studios were made to replicate the place where the production would take place. Studio 3E for Religious Services had the appearance of a religious building, however this could be changed for secular broadcasts when the vase of flowers (as shown in the photo) were used to replace the cross used for religious broadcasts:

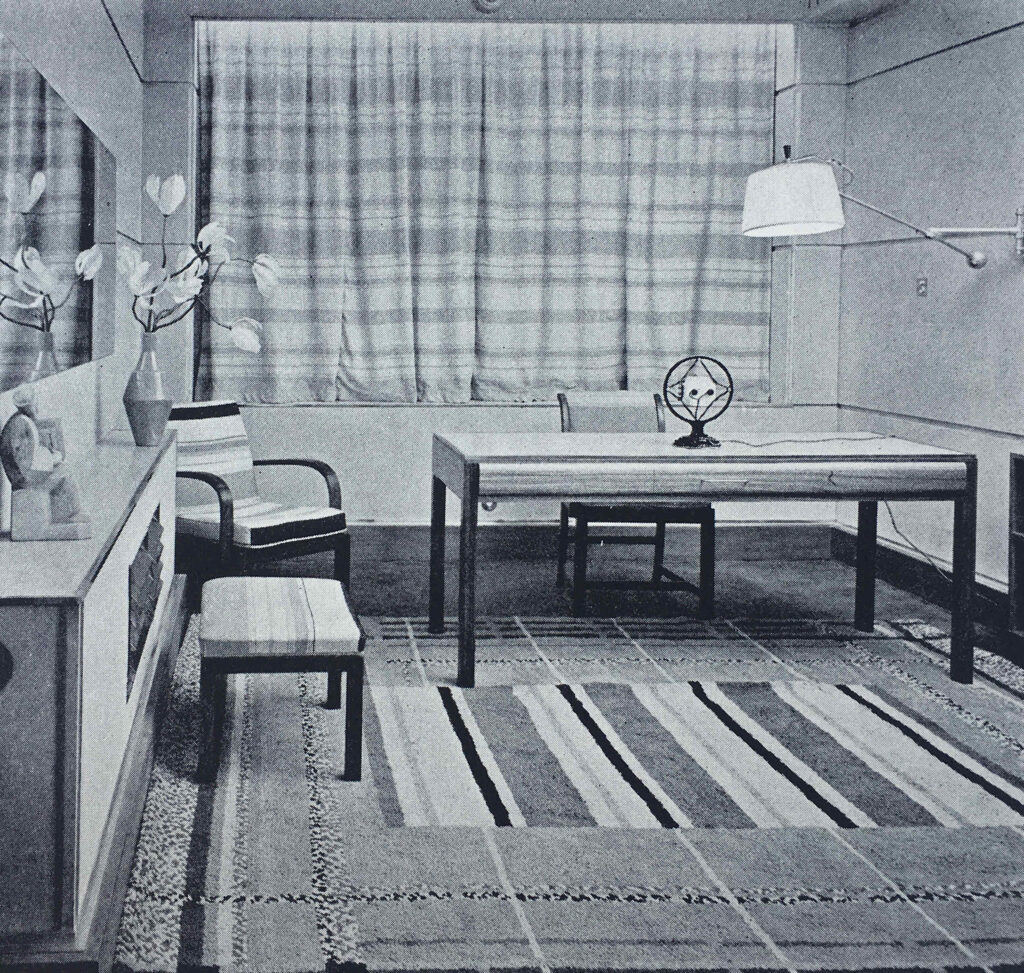

Studio 3B for Talks looks like a domestic setting. There were no windows behind those curtains.

The interior design of Broadcasting House was led by Raymond McGrath, an Australian born architect who led a team of young designers. They were given a degree of freedom with their designs, which resulted in a curious mix of homely and modernist features.

The studios are very different today, and in the past 90 years the function of broadcasting has taken over from the designs of 1932.

The Chairman’s Office:

Broadcasting House opened when the autocratic Sir John Reith was Director General. It was Reith who defined the BBC’s purpose as being to “inform, educate, entertain”. It was probably with some fear that employees would be summoned to the Director-General’s Office:

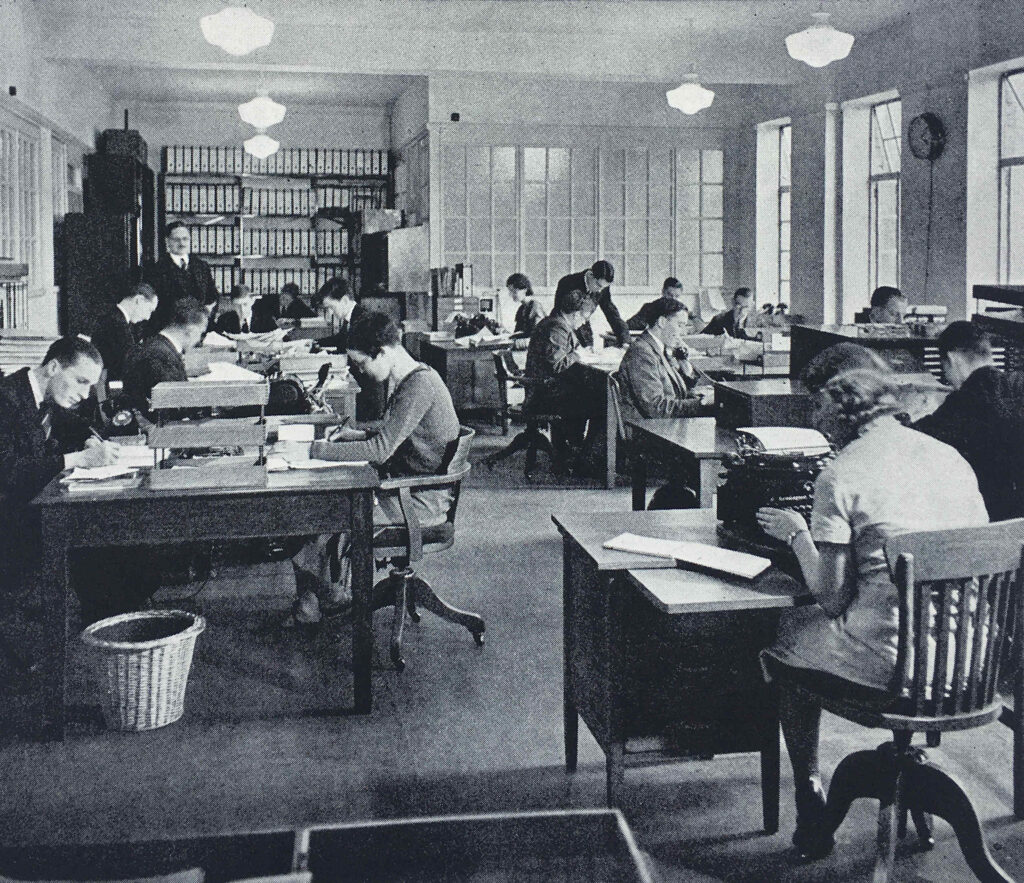

The majority of the photos in the book show empty studios and equipment rooms. Very new, and no people to be seen. The only photos with people are of some of the offices of Broadcasting House, such as the following photo of the Accounts Office.

Note in the photo the windows facing out. To the left would have been a corridor, then the brick wall of the inner core with the studios to avoid sound transmission from outside or from the internal offices.

The entrance hall from Portland Place, with staff lifts to the right and the Artists’ Foyer behind the pillar at the far end:

The Latin inscription on the right reads “This Temple of Arts and Muses is dedicated to Almighty God by the first Governors of Broadcasting in the year 1931, Sir John Reith being Director General. It is their prayer that good seed sown may bring forth a good harvest, that all things hostile to peace or purity may be banished from this house, and that the people, inclining their ear to whatsoever things are beautiful and honest and of good report, may tread the path of wisdom and uprightness.”

The Council Chamber:

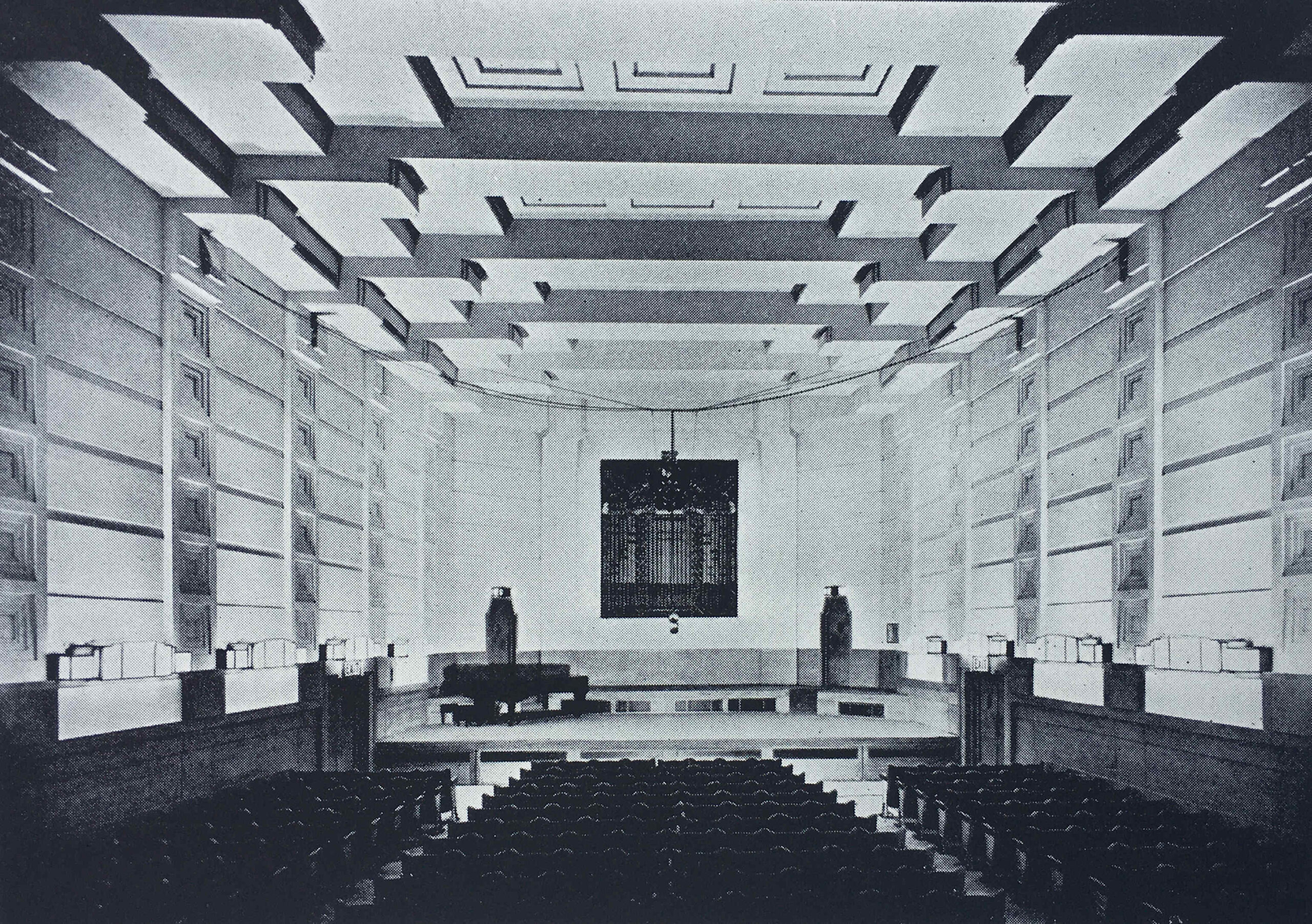

The Lower Ground floor provided access to the concert hall, from where concerts with a live audience would be broadcast. View towards the platform:

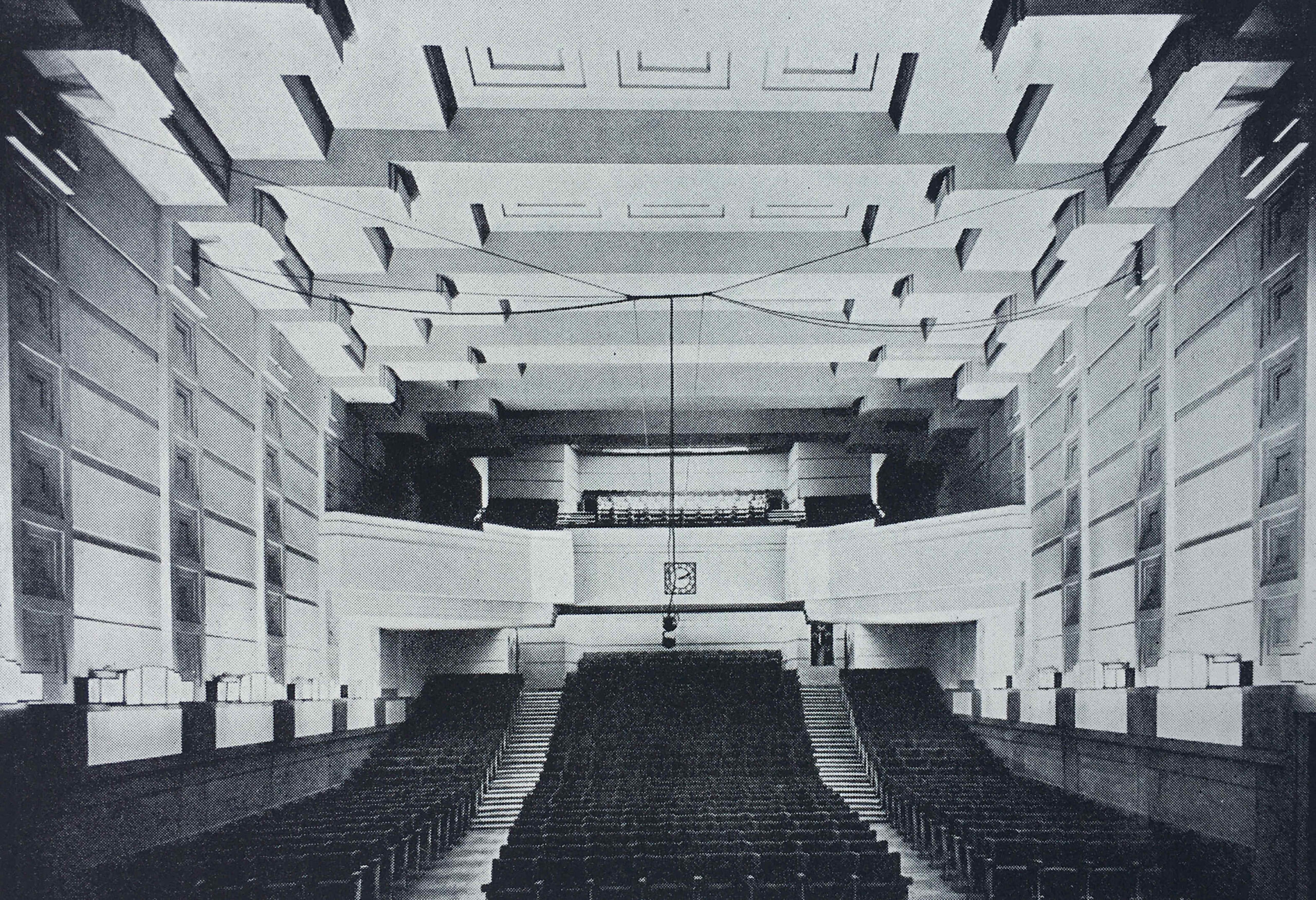

View towards the rear of the Concert Hall:

The Concert Hall is now known as the BBC Radio Theatre.

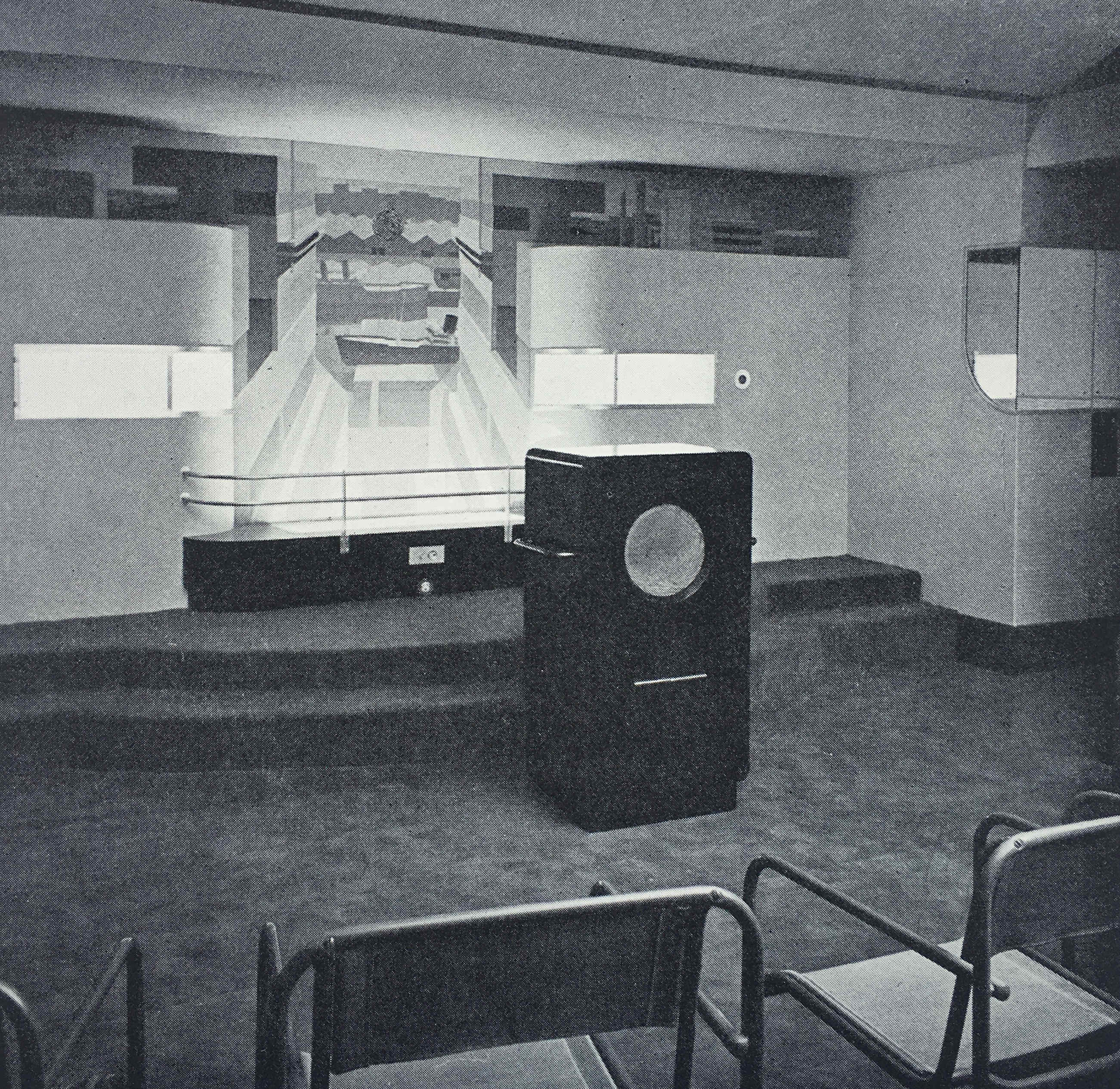

All the studios, along with other rooms involved with the broadcast process, were in the central core of the building, so they did not have windows and there was no natural light. The designs for these rooms attempted to address this with decoration, and in the following photo is Listening Hall 1, where a seascape had been added on the wall at which those listening would have been facing:

And in Listening Hall 2, gold and silver foil had been put on the walls to simulate the effect of sunlight:

Broadcasting House was built long before the days of electronically created sound effects. These were usually prerecorded on records as seen in one of the earlier photos, or involved making noises with physical objects.

Some sound effects needed a different approach such as the creation of an echo, or the impression that the sound was created in a large space rather than a small, sound proofed studion.

To provide echo effects, Broadcasting House had the Echo Room, where sound from a studio were played in the room which had reflective, resonant walls to bounce the sound, which was picked up by a microphone at the end of the room:

Broadcasting House was a leading edge facility at the time of construction for the new medium of broadcasting. It was however designed to meet John Reith’s view of the BBC, and the studios were designed for talks and discussions (nearly always by men), and for broadcasts of plays and concerts.

In the previous building at Savoy Hill it was common for those arriving to give a broadcast talk to be offered cigars, brandy and whisky before broadcasting – operating almost like a Gentleman’s Club.

News would become an increasing feature of the BBC, with the use of external agencies to provide news before the BBC developed their own internal news gathering capability.

As well as broadcasting to the country, broadcasting to the world would become an integral part of the BBC’s mandate, beginning with what was called the Empire Service, then the World Service.

The first broadcast specifically to the “Empire” was made from Broadcasting House on the 19th of December 1932, with John Reith speaking an introduction to the broadcast.

The BBC’s Centenary celebrations seem to have a different focus to 1972 when they celebrated 50 years.

In 2022 the focus seems to be more of the present day relevance of the BBC, with the breadth and depth of services provided. I suspect this is down to perceived threats to the BBC’s charter and the licence fee.

In 1972, the focus was more on the historical, showing the BBC almost as the official recorder of the great events of the previous 50 years.

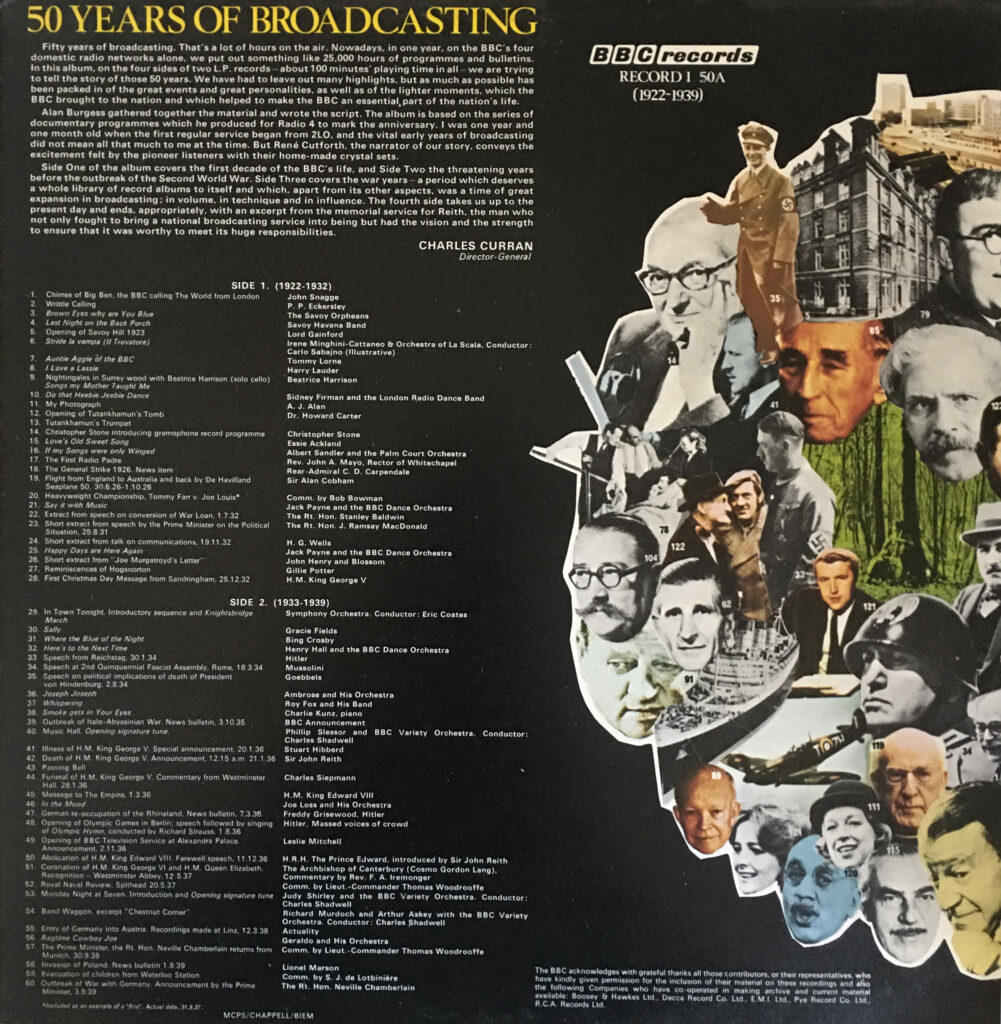

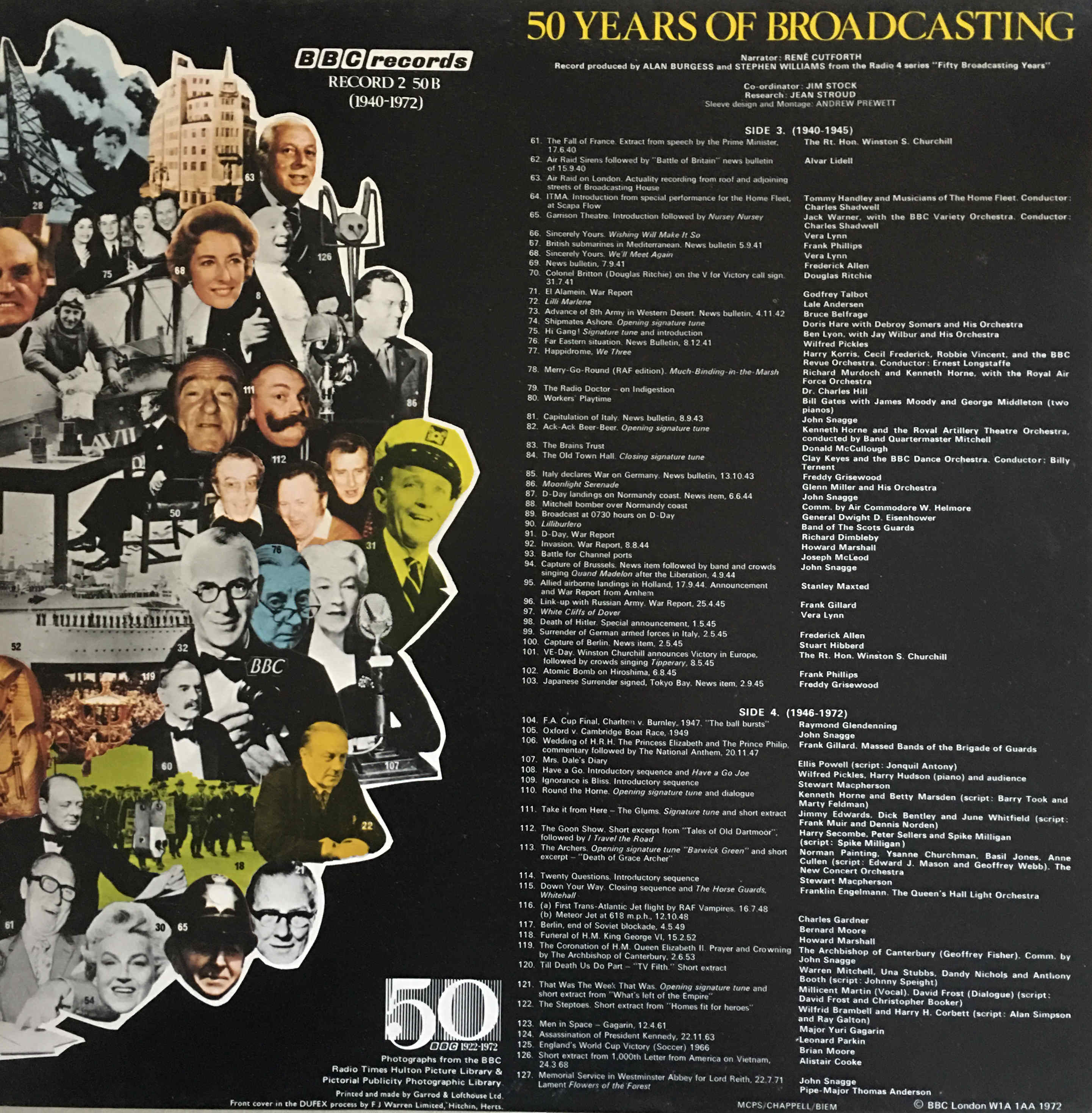

The BBC produced a double album in 1972 containing excerpts from key broadcasts of the Corporation’s first 50 years. I was given a copy at the time, a strange present given the age I was in 1972, but one I appreciate now for the historical context.

The double album opened up and inside there is a listing of all the broadcasts on the records.

Side 1 covers from 1922 to 1932, so pre Broadcasting House. Included are music from the Savoy Orpheans and the Savoy Havana Band, a recording of the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb, a news item from the 1926 General Strike, and the first Royal Christmas Message broadcast on Christmas Day in 1932.

Side 2 covers the six years from 1933 to 1939, when many of the recordings would have come from Broadcasting House. Along with recordings of musical items, the slow build up to war can be seen, from a 1934 speech by the Nazi Joseph Goebbels to Prime Minister Chamberlain’s announcement of the outbreak of war on the 3rd of September 1939.

Side 3 covers the Second World War, from the fall of France in 1940 to the final surrender of Japan in 1945.

Side 4 covers the period from 1946 to 1972 and includes an FA Cup Final, Oxford – Cambridge Boat Race, a Royal Wedding, Coronation and Funeral, shows such as the Archers, Goons and Twenty Questions. The First Man in Space, assasination of President Kennedy and England’s 1966 World Cup victory.

The final track on side 4 is appropriately the funeral of Lord Reith in 1971, who was instrumental in building up the BBC and was Director-General when Broadcasting House was planned and built.

The BBC does have some pages on their website on the 100 years, which can be found here.

Broadcasting House comes from a simpler time, when the BBC was virtually the only form of mass electronic media, with only newspapers for competition.

Today, the broadcaster has no end of competition, from multiple broadcasters, online services and streaming providers. Shifts from linear broadcasting to time shifting and on demand programming.

The BBC suffers accusations of bias from almost every part of the political spectrum. It seems to tie itself in knots in trying to tread carefully and appear impartial around contentious subjects.

The licence fee is indeed an anachronistic way to fund the organisation, but a fair alternative that provides sufficient funding for the organisation has yet to be proposed.

The BBC has made some huge mistakes over the years, but still has a global reputation for independence, and is a prime example of the country’s soft power.

After 90 years, it is brilliant that Broadcasting House is still part of the country’s broadcasting fabric, and with the BBC it must be an example of where the phrase “you never know what you’ve got, till its gone” strongly applies.