Mornington Crescent and the Corn Laws – two totally unconnected subjects, but there is a tentative connection to the Corn Laws not far from Mornington Crescent underground station which I will get to at the end of today’s post.

The name Mornington Crescent may bring little recognition, apart from a Camden station on the Northern Line, or the name may be instantly familiar from the BBC radio comedy “I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Clue” where it is the name of an invented game which requires the naming of a random set of locations to finally get to Mornington Crescent.

The entrance to Mornington Crescent station on Hampstead Road:

Mornington Crescent station was built as part of the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway, and opened on the 22nd of June 1907. The station is one of Leslie Green’s distinctive station designs with the exterior walls covered in red oxblood faience tiles. The station is now on the Northern Line.

The station takes its name from the nearby street of the same name, a street that was once prominent, but is now hidden away behind a rather glorious 1920s factory.

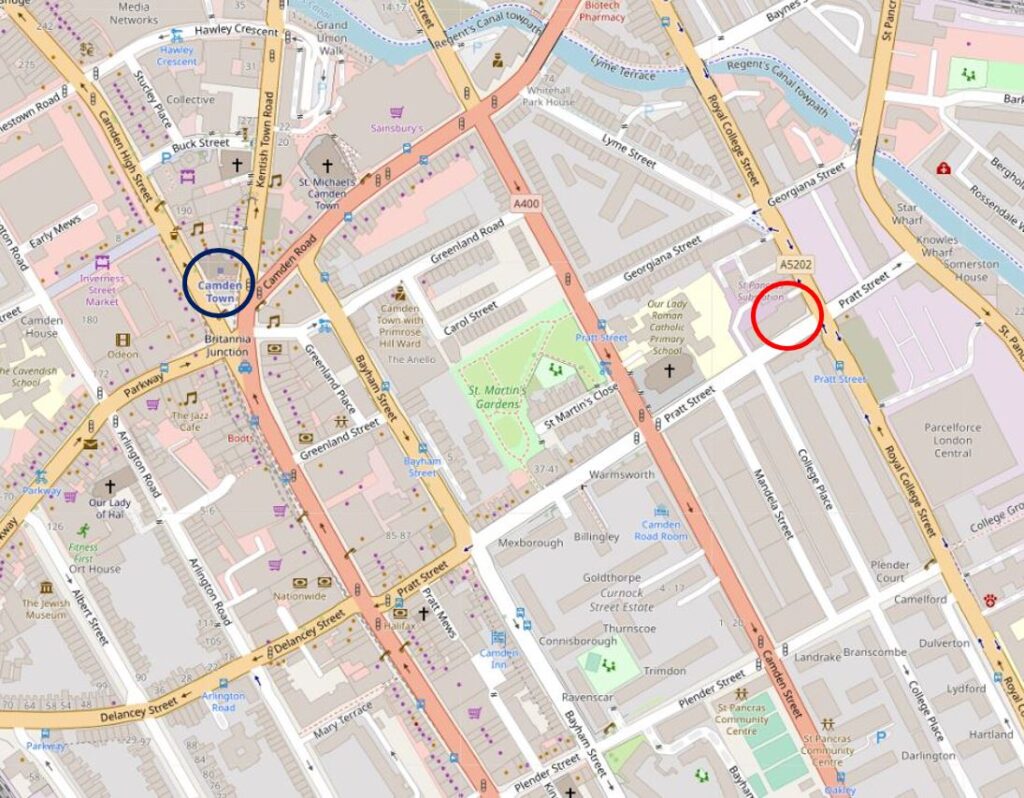

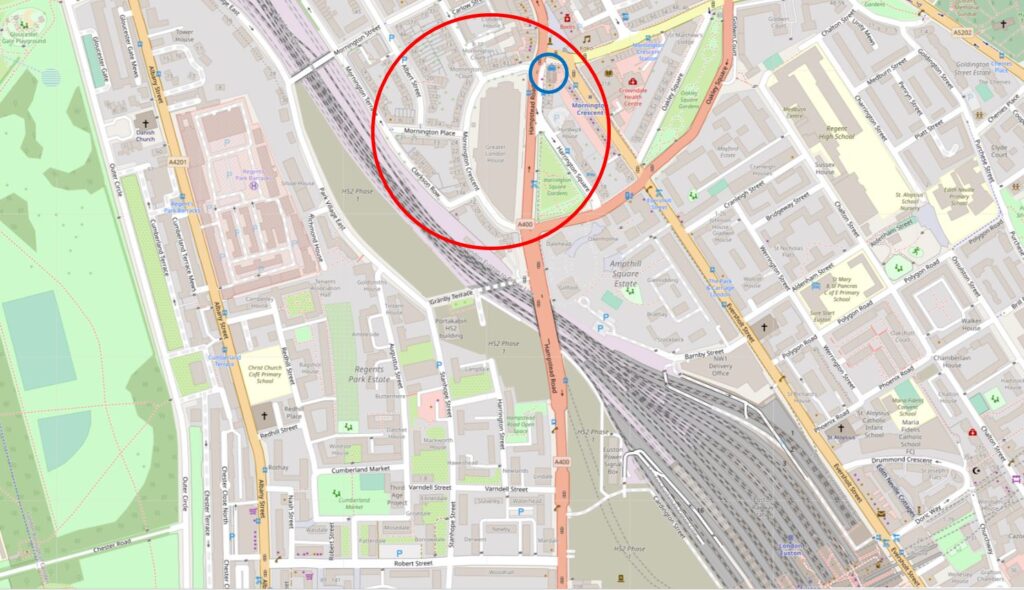

The location of the station is shown by the blue circle in the following map, and the larger red circle shows the area covered in this week’s blog (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

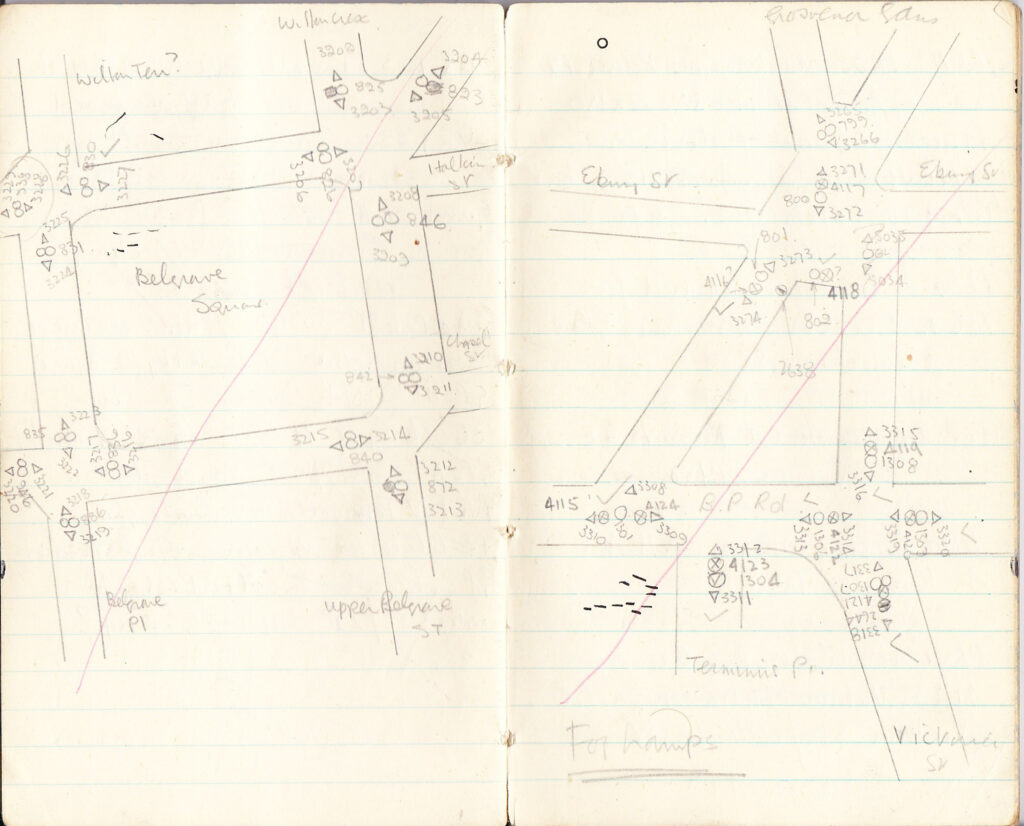

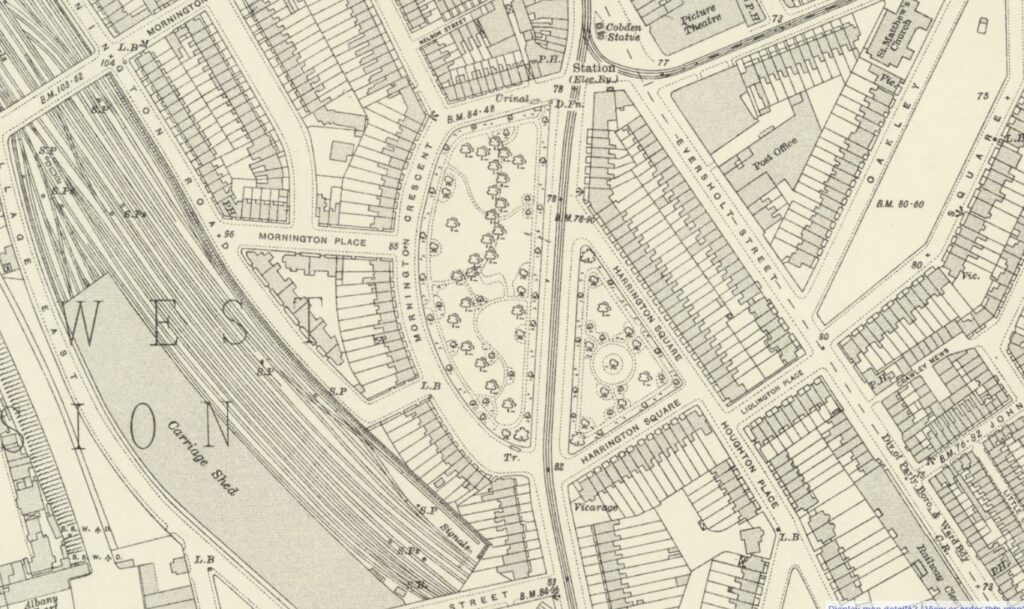

Mornington Crescent (the street, not the station) is the curved, crescent shaped street that starts to the left of the station, curves around a large grey block and then rejoins Hampstead Road. The following extract from the 1894 Ordnance Survey map shows the area in the late 19th century, with Mornington Crescent then looking onto a garden, the larger part to the left of Hampstead Road and a small part to the right (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“).:

The large grey block in the map of the area today, and which now occupies the area where the garden was located is the wonderful old Carreras cigarette factory, now offices:

The Carreras brand dates from the early 19th century when the Spanish nobleman Don José Carreras Ferrer started trading cigars in London. The business expanded into other forms of tobacco such as snuff and cigarettes, and became a significant business during the late 19th century.

What really drove the brand’s expansion, and the opening of the Mornington Crescent factory was the transformation of Carreras to a public company in 1903, when a Mr. W. J. Yapp (who had taken over the company from the Carreras family) and Bernhard Baron (of Jewish descent, who was born in what is now Belarus on the Russian border, who had moved to the United States and then to London), became directors of the company.

Whilst in New York, Bernhard Baron had invented a machine that could manufacture cigarettes at a faster rate than existing machines, and in London the Carreras company was the only one that took on the new machines, other tobacco companies preferring to stay with their existing means of production, or machines over which they held monopolies.

By the start of the 1920s, Baron was Chairman of the company and wanted to create a large, modern factory, which would enhance the brand’s reputation for the purity and quality of their cigarettes, and provide a good working environment for the company’s employees.

The result was the new factory on the old gardens between Mornington Crescent and Hampstead Road.

Designed by the architectural practice of Marcus Evelyn Collins and Owen Hyman Collins, along with Arthur George Porri who acted as a consultant, the design of the building was inspired by the archeological finds in Egypt during the 1920s, with the tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun being discovered in 1922.

The building was one of the first (and I believe the largest at the time) building to use pre-stressed concrete, and also to be fitted with air conditioning and dust extraction equipment.

The innovative construction of the building, and the technologies used to maintain the internal environment were mentioned in all the major news reports that covered the opening of the building on the 3rd of November 1928:

“Carreras new factory at Camden Town, which was opened by Mr. Bernhard Baron, the chairman of the company, constitutes not only the largest reinforced concrete building under one roof in Great Britain, but also that rare thing – the realisation of one man’s dream.

Mr. Baron is a practical idealist. He set out to make cigarettes, he wanted them made in the best way, and in the best conditions. He wanted the people who made them to be happy in their work, it has all come true.

The opening ceremony was as impressive in its simplicity as the new building is in its efficiency and design. Mr. Baron performed it himself, not so much as chairman of the company, but as the father of the three thousand employees who have helped him to achieve success. He said, at the luncheon, that he felt it a great honour to have opened the factory, and that he wanted his employees about him at that moment to share his pleasure. That was why he decided on a simple ceremony, a family celebration, as it were, of the culmination of one stage of his life’s work.

Carreras new building embodies all that is best in factory design. It is well lit, and well ventilated and as healthy as it is possible to make it.

Most important of all, it has been fitted with an air conditioning plant which is the only one of its kind in the British tobacco industry, and which ensures a consistently ideal atmosphere for the manufacture of the perfect cigarette. The air which enters the building is first washed clean with water. It is then adjusted to the required temperature and humidity. Outside, London may be shivering or sweltering, damp or dusty. Inside, every day is a fine day; all weather is fair weather. It is well known that the English climate is the best in the world for the manufacture of tobacco; it can now be said that Carreras climate is the best in England.

The façade of the building, which stretches five hundred and fifty feet along Hampstead Road, is something fresh in London architecture – a conventionalised copy of the Temple of Bubastis, the cat headed goddess of Ancient Egypt.”

I have read several modern references to the opening of the building which include that the Hampstead Road was covered in sand, there were chariot races and Verdi’s opera Aida was performed, however I cannot find these mentioned in any of the news reports from the time that covered the opening of the building. As seen in the above report, the “opening ceremony was as impressive in its simplicity as the new building is in its efficiency and design“.

The opening of the factory was seen as an improvement to the area, although it had resulted in the loss of the open space between Mornington Crescent and Hampstead Road, as newspapers reported that “When the move to save the London squares was first begun, Mornington Crescent was cited as one of London’s losses. It had been acquired by Mr. Bernhard Baron as the site of his new factory. I doubt whether had it been saved we Londoners would have gained anything. Now when you come out of the Tube station, the eyesore of that dirty bit of green, backed by decaying Victorian basement houses is no more. Instead, there is the finest factory in London, an architectural triumph for Mr. Marcus Collins, the culmination of a life’s work for Mr. Baron and a model workplace for his 3,500 employees.”

The Mornington Crescent factory remained in operation until 1959 when Carreras merged with Rothmans, and cigarette production was moved to a factory in the new town of Basildon in Essex.

The building was sold and in 1961 it became office space, with the name of Greater London House, and all the Egyptian decoration was either removed or boxed in.

This would remain the fate of the building until the late 1990s when a new owner refurbished the building and restored the Egyptian decoration that we see today, as close as possible to the original design.

In the following photo of the main entrance to the building, two black cats can be seen on either side of the steps:

These are not the original cats as following the closure of the factory in 1959, one was transferred to the new factory in Basildon whilst the other was shipped to a Carreras factory in Jamaica.

After walking north along Hampstead Road, through the works for HS2, the restoration of the Carerras building has retained some wonderful 1920s architecture to this part of Camden, however it has almost completely hidden Mornington Crescent, and a walk along this street is my next destination, starting from the northern end, opposite the underground station, where the Lyttleton Arms now stands:

If you look closely at the top corner of the building, you will see the original name of the pub as the Southampton Arms. The pub was renamed the Lyttleton Arms in honour of the jazz musician and radio presenter, Humphrey Lyttleton, who was also the long running host of the radio panel game I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue from 1972 until his death in 2008, the show that included the game Mornington Crescent.

During the 1920s, the same decade that the Carerras factory was built, the Southampton Arms, as the pub was called, was one of the centres of conflicts between the gangs who tried to control race course betting, including the Clerkenwell Sabini Brothers and Camden’s George Sage.

The following report from the St. Pancras Gazette on the 6th of October 1922 illustrates one of the incidents:

“RACING MEN’S FEUDS – At Marylebone on Tuesday, Alfred White, Joseph Sabini, George West, Simon Nyberg, Paul Boffa, and Thomas Mack made their eighth appearance on the charges of shooting George Sage and Frederick Gilbert with intent to murder, at Mornington-crescent, Camden Town, on August 19, having loaded revolvers on their possession with intent to endanger life, and riotously assembling.

Helen Sage, wife of one of the prosecutors, said she was talking to her husband outside the Southampton Arms at Camden Town when several taxicabs drove up and a number of men alighted. She then heard a shot, but could not say who fired, as it was dark. The witness admitted that she told the police that West and White fired the shots, but now declared that this statement was untrue.”

Strange that Helen Sage, who was presumably the wife of the shot George Sage declared that her statement was untrue. Possibly some witness tampering or gangs not giving evidence against each other, preferring their own form of justice.

The first section of Mornington Crescent (from the north) is not part of the original, and this will become clear with the architectural style as we walk along the crescent. These later houses are smaller and less impressive than the original part of the crescent:

And after crossing the junction with Arlington Road, we can now see the original terrace of buildings from when Mornington Crescent was laid out:

In the middle of the above terrace there is a blue plaque, to Spencer Frederick Gore, the painter, who lived in the building between 1909 and 1912.

Gore painted the view from his house across the gardens and the view along Mornington Crescent. The Tate have one of his paintings of the gardens online here.

The following view is of the continuation of the terrace houses along Mornington Crescent, at the junction with Mornington Place:

Construction of Mornington Crescent started in the early 1820s and was not complete until the 1830s. It is named after Richard Colley Wellesley, the Earl of Mornington and Governor-General of India. He was also the eldest brother of the Duke of Wellington, so was from an influential family.

Mornington Place heads up to the rail tracks to and from Euston Station:

The street was built around the same time as Mornington Crescent and comprises smaller three storey terrace houses, although with some interesting architectural differences:

At the end of the street, we can look over the brick wall and see the rail tracks, with HS2 works continuing on the far side:

Looking back down Mornington Place towards the old Carreras factory – originally this view would have had the gardens at the end, through which Hampstead Road would have been seen:

Albert Street is a turning off Mornington Place, a terrace of new buildings occupies a space which on the 1894 OS map appears to have been an open space with a larger building set back from the road.

There is a smaller brick building between the modern terrace and the large brick terrace of houses. This is Tudor Lodge:

Tudor Lodge is Grade II listed. It was built between 1843 and 1844 for the painter Charles Lucy, and believed to be to his own design. The plaque on the building though is to George Macdonald, Story Teller, who lived in the building between 1860 and 1863. An interesting building in a street of mainly 19th century terrace houses.

Rather than walk along Albert Street, I returned to Mornington Crescent and the rear of the Carreras factory, where there is a chimney:

I have not been able to confirm whether or not the chimney is original, however rather than being the more common round chimney it seems to have the appearance of an obelisk, similar to Cleopatra’s Needle on the Embankment, so if original, the chimney continues the Egyptian design theme of the building.

Almost at the end of Mornington Crescent now, and the final row of terrace houses before reaching the Hampstead Road. The following photo gives an indication of the changes to the outlook of the houses when the Carreras factory was built. Rather than looking out on the gardens and across to Hampstead Road, they now had the view of the rear of the large factory.

By the time the factory was built, many of the houses were almost 100 years old, and their condition was not that good, many were subdivided into flats. Their condition would deteriorate further during the 20th century, there was some bomb damage along the terrace in the Second World War and it has only been in the last few decades that many of the houses have been restored.

In this final terrace of Mornington Crescent there is another blue plaque, to another artist, this to Walter Sickert, recorded as a painter and etcher:

Sickert was at the core of the Camden Town Group of artists, a short lived group of artists who gathered mainly between 1911 and 1913.

The building at the southern end of Mornington Crescent, which has a Hampstead Road address is of a much more impressive design, presumably as it was at a more prominent position. Just seen on the wall behind the tree is another plaque:

This plaque is to the artist George Cruikshank, who lived in the building from 1850 until his death in 1878.

On the opposite side of the street to the house in the above photo is a water trough for horses. I took a photo, but was not intending to include the photo in today’s post:

Until i found the following photo in the Imperial War Museum collection showing a horse and cart of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway pausing to drink at the trough, with Mornington Crescent in the background of the photo:

Pleased I found the photo, but rather frustrating as if I had found it before visiting I could have taken a similar view, however it does give a good impression of Mornington Crescent in 1943.

Returning to the space opposite the underground station, we can look south and get a view of the overall size of the Carreras factory, a building that occupied the site of the gardens between the crescent and Hampstead Road.

The space just to the north of Mornington Crescent underground station is the junction of Hampstead Road and Camden High Street, along with Crowndale Road and Eversholt Street.

To the east of the underground station at the road junction is the club / music venue Koko:

Originally the Camden Theatre when built in 1900, it then had a series of owners as both a theatre and a cinema, until 1945 when it was taken over by the BBC and used as a theatre to record radio programmes, including the Goon Show, with the very last Goon Show being recorded in the theatre on the 30th April 1972.

The BBC left in 1972, and from 1977 the building has been a live music venue, firstly as the Music Machine, then the Camden Palace and now Koko.

The building has hosted very many acts in its long history, including the Rolling Stones and the Faces, with my most recent visit to the Damned in February 2018 (and whilst researching the post I found a review of the Damned concert here).

The title of this post is Mornington Crescent and the Corn Laws, and it is only now that I can get to the final part of that title. In the open space opposite the underground station is a statue:

The statue is of Richard Cobden and was erected in 1868. Cobden did not have any direct relationship with Camden, however it was an impressive location for a statue, and it was put up due to the residents of Camden’s appreciation of Cobden’s work in the repeal of the Corn Laws.

The Corn Laws were a set of laws implemented in 1815 by the Tory Prime Minister Lord Liverpool due to the difficult economic environment the country was in following the wars of the late 18th and early 19th century.

The Corn Laws imposed tariffs on imported grains and resulted in an increase in the price of grain, and products made using grain. These price increases made the Corn Laws very unpopular with the majority of the population, although large agricultural land owners were in favour as they made a higher profit from grain grown on their lands.

The Corn Laws were finally repealed by the Conservative Prime Minister Robert Peel in 1846, and they reflect a tension between free trade and tariffs on imports that can still be seen in politics today.

Richard Cobden was born on the 3rd of June, 1804 in a farmhouse in Dinford, near Midhurst in Sussex. His only time in London appears to have been after his father died, when Cobden was still young, and his was taken under the guardianship of his uncle who was a warehouseman in London.

Not long after he became a Commercial Traveler, and then started his own business which was based in Manchester, which seems to have been his base for the rest of his commercial success.

During his time in Manchester Cobden was part of the Anti-Corn Law League and was known as one of the leagues most active promoters.

The Clerkenwell News and London Times on the 1st of July 1868 recorded the unveiling of the statue:

“The Cobden memorial statue which has just been erected at the entrance to Camden Town was inaugurated on Saturday. Although this recognition of the services of the great Free Trade leader may have been looked upon in some quarters as merely local, the gathering together of some eight to ten thousand people to do honour to his memory cannot be regarded in any other light than that of a national ovation.

The committee had arranged that the statue of the late Richard Cobden at the entrance to Camden Town – with the exception, perhaps, of Trafalgar Square, one of the finest sites in London – should be unveiled on Saturday, that day being understood to be the appropriate one of the anniversary of the repeal of the Corn Laws, and the event was so popular that the surrounding neighbourhood was gaily decorated with flags for the occasion. The windows and balconies of Millbrook House, the residence of Mr. Claremont, facing the statue, had been placed at the disposal of Mrs. Cobden and her friends, including her three daughters.

A special platform had been created in front of the pedestal, covered with crimson cloth, and in the enclosure in front the band of the North Middlesex Rifles were stationed, and performed whilst the company assembled.

The report then covers at some length, all the speeches made which told the story of Cobden’s life and his actions in the repeal of the Corn Laws. There were many thousands present to witness the event, and at the end; “after the vast assembly had dispersed Mrs. Cobden, accompanied by Mr. Claremont, the churchwardens, and other friends, walked round the statue and expressed her high gratification at the fidelity of the likeness.”

The statue was the work of the sculptors W. and T. Willis of Euston Road, and is now Grade II listed.

I suspect if you turn right out of the entrance to Mornington Crescent underground station, you will be surprised to know that the space in front of you was compared to Trafalgar Square as one of the finest sites in London.

It always fascinates me how much history there is at almost any place in London, and Mornington Crescent is no exception. Whether the arrival of the underground, the architecture of the Carreras factory, race course gangs at the pub, historic streets, entertainment venues and radio shows and the statue of a free trade advocate – all within a short walk of Mornington Crescent.