The streets north of Cheyne Walk in Chelsea were a centre for the manufacture and decoration of china during the 18th and 19th centuries. I wrote about one factory in my post on Cheyne Row, and in today’s post I come across another, earlier factory where Chelsea china and porcelain were manufactured in the 18th century.

I am in Lawrence Street, to find the location of one of my father’s photos from 1949:

This is the same scene today:

I was standing on the steps up to one of the houses to try to recreate the same view, with the railing shown to the lower left of both photos. The plant was growing up from the small garden space in frount of the house, I thought it best not to try to bend or break to remove from the view.

The view is much the same (although whilst I was sure I was standing in the same place, the perspective is slightly different between the two photos, possibly due to camera and lens being very different).

The major difference is the number of cars which now seem to line almost every street in Chelsea, making is really difficult to get good, full length photos of the buildings. The single car in 1949 has now multiplied many times.

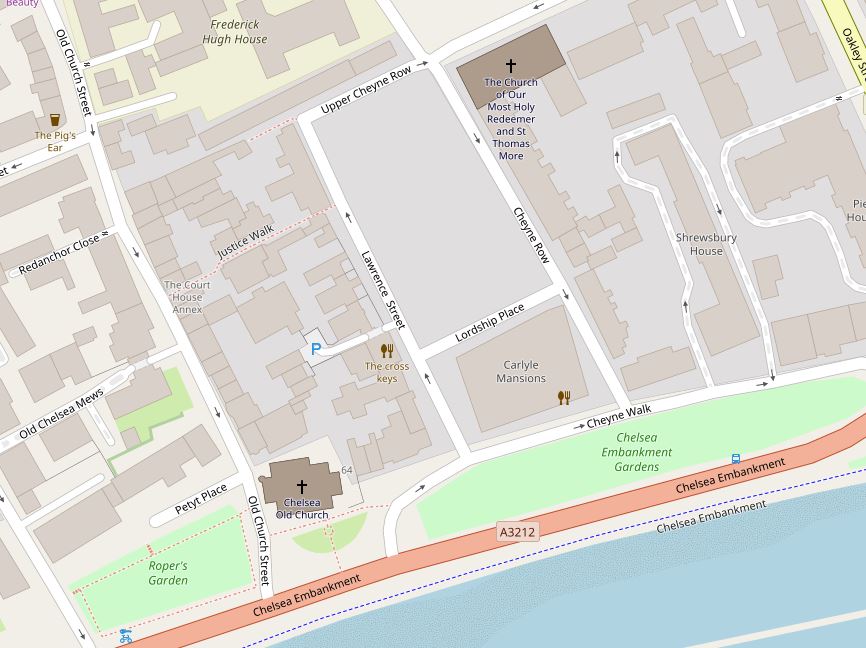

Lawrence Street can be found in the following map, running north from Cheyne Walk in the centre of the map:

The street name comes from the Lawrence family who lived in the manor house that was on the land to the north of Lawrence Street and Upper Cheyne Row.

The first Lawrence to arrive in Chelsea was Thomas Lawrence, a London goldsmith who arrived in the sixteenth century, the manor remained in the hands of the Lawrence family until 1725. Thomas was originally from Shropshire, but moved to London where he married Martha Sage. They would go on to have eleven children, with only five surviving.

The Lawrence Chapel in the nearby Chelsea Old Church is named after Thomas and includes a memorial to him

The manor house was replaced by Monmouth House (after the Duchess of Monmouth who occupied the house on the site from 1714).

As you walk up Lawrence Street from Cheyne Walk, the age of the houses gets older as you approach the top of the street. The size of the houses also reduces, starting with the four storey house shown below:

To these smaller, terrace houses at the top of the street:

It may have been one of these houses that was the subject of an advert in the Morning Advertiser on the 13th January 1818:

“To be LET a small modern genteel HOUSE, at 26 guineas per ann, well laid out for saving of window lights, box window to the parlour, and French sashes, and balcony to the drawing room. This house contains six good rooms, two kitchens, with dry wine and coal vaults, is in a very healthy situation, being in Lawrence-street, Chelsea, from whence a Stage goes six times a day to town – Enquire of Mr Lewer, 30, Eaton-street, Pimlico.”

At the top of Lawrence Street is the junction with Upper Cheyne Row.

From here we can look back on the houses on the western side of the top of the street.

There is a London County Council blue plaque on the end house:

Tobias Smollett was a Scottish poet and novelist who originally had a career in medicine, including as a naval surgeon which provided the opportunity to travel widely.

Before Chelsea he was living in central London with his wife and daughter, however with his only daughter suffering from tuberculosis, the family moved to Chelsea with the hope that the air would benefit his daughter. Living in Chelsea did not have the desired effect, and his daughter died aged 15, after which Smollett left Chelsea, and with his wife, went travelling in France “overwhelmed by the sense of domestic calamity, which it was not in the power of fortune to repay.”

The plaque also makes reference to the manufacture of Chelsea China at the north end of Lawrence Street.

It is not clear when the production of china started in Chelsea, however the first recorded owner of the Chelsea china works was Charles Gouyn who arrived at the works in 1745. In 1749, the works were managed by Nicholas Sprimont who had arrived in London from Belgium. Originally a silversmith he changed his trade to working with clay. His influence changed the design of Chelsea china, with his experience of the design of silver products being mirrored in the designs of Chelsea china and porcelain.

The range and output of the Chelsea China Works increased steadily during the 1750s and received Royal patronage from George II. Royal support continued with George III who purchased a dinner service for the considerable sum of £1,200 as a gift for the Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

Nicholas Sprimont retired a wealthy man in 1769 and the Chelsea China Works was taken over by William Duesbury who had apparently arrived from Derby. Duesbury ran the Chelsea works for a further ten years, however in 1779 the lease on the factory premises expired, and within five years the Chelsea China Works closed.

William Duesbury returned to Derby, taking many of the moulds with him, and the buildings of the china works were demolished.

Fragments of china were found in 1970 in the garden of number 15 Lawrence Street (the house to the left of the house with the blue plaque) which helped to confirm the location of the Chelsea China Works.

The British Museum has a number of examples of the output from the Chelsea China Works, starting off with one of the earliest examples from 1745 – a “goat and bee” jug made from soft paste porcelain. Goats are on either side of the base and a bee is climbing up to the lip of the jug.

The two sides of a porcelain vase, dating from 1750:

A rather ornate porcelain clock case dating from between 1752 and 1758:

The following pair of figures are known as the “Tyrolean Dancers” and date from the years 1755 to 1757:

A porcelain dish dating from between 1750 and 1752:

For a brief period, Chelsea was manufacturing china and porcelain probably as good as anywhere else in the country, however after the closure of the Chelsea works, it was the factories around Derby and Stoke-on-Trent, where companies such as that run by Josiah Wedgwood would further develop the technical skills and scale of manufacturing to continue in business for the following centuries.

Lawrence Street would continue as a quiet, residential street.