Hogarth’s House in Chiswick has long been on my list of places to visit and a couple of weeks ago I had the opportunity. The drawings of William Hogarth have featured in a number of my posts. His observations provide a remarkable insight into 18th Century London society so I was very pleased to have the time for a trip out to Chiswick.

Hogarth’s House is next to the busy six lane road that leads from the Hogarth Roundabout to the M4, one of the main entry and exit routes into London from the west. On the day of my visit it was strangely quiet. An overnight accident next to the roundabout had resulted in a fuel spill on the road which was consequently closed for resurfacing. Very long queues of traffic led from the roundabout back into London, but adjacent to Hogarth’s House all was quiet.

The house can easily be missed, but once seen it is clear that here is a building worth visiting. Viewed from the road in the photo below, the house is on the left, with a high garden wall running to the right. As with so much of London, the house is surrounded by construction activities with new apartment buildings rising in the background.

The area of ground on which the house is built was originally part of a larger orchard. James Downes, a baker, inherited the land in 1713 and built the house in one corner of the orchard.

The house was purchased by Hogarth in 1749 from the widow of Georg Andreas Ruperti who had purchased the house new in 1717. Ruperti was the Pastor at the German Lutheran Church at the Savoy and was obviously a wealthy man as on his death in 1732 there was a sale of many of his possessions including 1,090 lots of books.

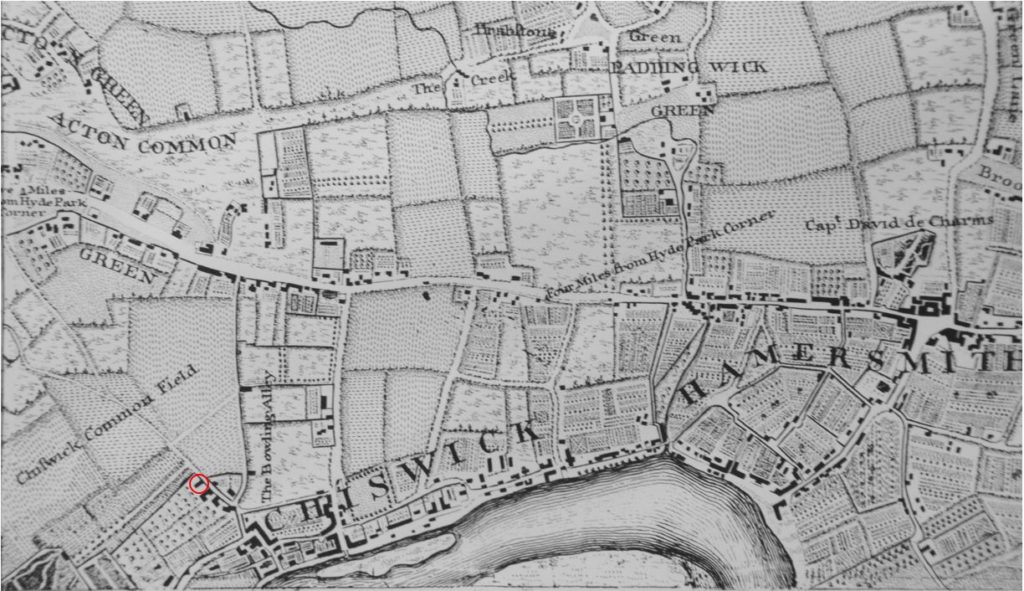

The following extract is from John Rocque’s map of 1746, three years before Hogarth purchased the house. The map shows the house to the northwest of the village of Chiswick, the last in the lane approaching Chiswick Common Field. I have circled the house in red. As can be seen, apart from building along the river, much of this area was still very rural.

The following print (©Trustees of the British Museum) titled “Published as the Act directs by Jane Hogarth at the Golden-head Leicester Fields 1st May 1781” shows the view across the Chiswick Common Fields to Hogarth’s House which can be seen to the left of centre with the garden wall running to the right. This is the rural scene that Hogarth would have known. Today, the Hogarth Roundabout is on the far left and the six lane A4 runs from left to right across the scene, immediately in front of Hogarth’s House and the garden wall.

Hogarth had been living in central London and his choice of a house in Chiswick may have been due to the heat wave in the summer of 1749 prompting a move to an area that was at the time mainly countryside, as well as Chiswick being the home to several of Hogarth’s friends.

The house, when purchased by Hogarth was a three storey brick-built building with wood paneled walls. Hogarth extended the house in 1750 by adding an additional room to each floor and a building in the garden included a first floor room which Hogarth used for painting.

The extension to the house can clearly be seen by the difference in mortar and brickwork. Hogarth also added the large oriel window in the centre of the house.

Hogarth lived in the house for 15 years until his death in 1764. His wife Jane continued to live in the house until her death in 1789 when the house was inherited by Jane’s cousin Mary Lewis who had supported Jane by running the business to continue the sale of Hogarth’s prints. As well as the house, Mary also inherited the printing plates.

After Mary’s death in 1808, the house passed to Richard Lovejoy who may well have been Hogarth’s doctor. Lovejoy only had the house for 4 years until his death in 1812.

The house then went through a succession of owners during the 19th Century. The area around the house and the rest of Chiswick was changing fast. The construction of houses and the growth of industry including the nearby Griffen Brewery of Fuller, Smith and Turners (1828) was sweeping away the fields that Hogarth would have known.

The house was at risk of destruction in 1901 when plans were proposed for the building of new homes on the land occupied by Hogarth’s House. A committee was formed to try to raise funds to buy the house, however not enough was raised and after an appeal by The Chiswick Times, a Lieutenant Colonel William Shipway who also lived in Chiswick, purchased the house for £1,500. Shipway also paid for the restoration of the house, which was then opened to visitors in 1904.

William Shipway had to take legal action to preserve the house. From the London Daily News of the 26th March 1902:

“Colonel Shipway applied to Mr. Justice Buckley in the Chancery Division yesterday for an injunction to restrain Mr. Percy from excavating some land at Chiswick in such a way as to endanger the stability of Hogarth House. The defendant is a builder, and he had acquired some land at the rear of Hogarth House, and Colonel Shipway contended that he was working the valuable building sand which was beneath the surface in a manner which was likely to let Hogarth House down, and cause great damage. This the defendant denied. Mr. Justice Buckley, after hearing evidence said that there had been movement observed in the house by reason of the removal of saturated sand, and though the damage was slight it was sufficient to entitle the plaintiff to an injunction, which he accordingly granted, with costs.”

In 1909 Shipway made a gift of the house to Middlesex County Council with custodians living in the house rent free in return for showing visitors around the house.

The house suffered considerable damage in 1940 when a landmine fell nearby. It was repaired in 1951 and reopened the same year. In September 2008 the house closed for further restoration work, interrupted by a fire in 2009, with the fully restored house finally opening in 2011.

As well as being saved from demolition and damage by 2nd World War bombing, during the 20th Century the house also survived the building of the Hogarth Roundabout and the transformation of the road running alongside the house from the original Hogarth Lane into the A4 which was subsequently widened into the six lane road we see today. The house has also been surrounded by new building, and the Hogarth Business Park between the house and the roundabout. Building directly adjacent to Hogarth’s House continues to this day.

The view of Hogarth’s House from the end of the garden.

The ground floor dining room:

Hogarth’s bedroom:

There are numerous copies of Hogarth’s drawings around the house. Here the six prints from the series “The Harlot’s Progress”, the first of his sets of prints where each individual print told part over an overall story. The Harlot’s Progress sold 1,240 sets of prints at a price of one guinea per set.

Looking out from the large oriel window:

Portraits of Hogarth’s sisters painted by Hogarth in 1740. Anne on the right who died in 1771 and Mary on the left who died in 1741. The sisters ran a dress shop in Smithfield and then in Cranbourn Street in Leicester Fields (now between Long Acre and Leicester Square.

The house has been superbly restored. The wood paneling, layout of the floors and shape of the rooms does provide a good impression of what the house would have looked like when Hogarth was in residence.

Toy theatre and more prints:

View from the 1st floor looking across the entrance to the house to the very quiet A4. Normally there are six lanes of traffic running along this road into and out of London. Very different from the narrow lane and fields that Hogarth would have seen through this window.

An impression of what the lane that originally ran alongside the house was like in the 19th Century can be gathered from a newspaper article in the Daily Gazette, dated the 20th September 1878, where Hogarth’s House is described as “At a short distance north-west of the church, in a narrow and dirty lane leading towards one entrance to the grounds of Chiswick House still stands the red-bricked house which was once occupied by Hogarth, and still bears his name”.

A view from the rear of the house shows the unusual shape of the building. Hoarding reaching up to the house shows what is being built immediately to the rear.

Hogarth is buried in the nearby church of St. Nicholas. To reach the church, it was a short walk back to the Hogarth Roundabout, cross the roads by way of the underpass and walk down Church Street with the Fuller, Smith and Turner brewery on the left. The church is towards the end of this road on the right before reaching the River Thames.

The tomb and monument to Hogarth is just to the side of the church.

Inscriptions on the side of the monument read:

“Here lies the body of William Hogarth Esq. who died October the 26th 1764 aged 67 years” and “Mrs Jane Hogarth, Wife of William Hogarth Esq, died the 13th of November 1789 aged 80 years”.

The main inscription is an epitaph to Hogarth written by his friend, the actor David Garrick:

“Farewell great Painter of Mankind, Who reach’d the noblest point of Art, Whose pictur’d Morals charm the Mind, And through the Eye correct the Heart.

If genius fire thee, Reader, stay, If nature touch thee, drop a tear; If neither move thee, turn away, For HOGARTH’S honour’d dust lies here”.

In looking for Hogarth’s tomb I made the mistake of walking down the northern side of the church to the large entrance shown in the photo below. The churchyard is split into two sections, the original churchyard around the church and a much large extension to the churchyard that is accessed through this entrance.

Plaques on the pillars of the entrance record that an additional acre of ground was given to the Parish of Chiswick by His Grace the Duke of Devonshire in 1871 and that the churchyard was then enlarged by the “addition of twenty five perches of ground given to the Parish by His Grace William Spencer in 1888”.

This extended churchyard is now a busy mix of very different styles of gravestone and monument.

Part of the inscription on Hogarth’s tomb reads “If genius fire thee, Reader, stay, If nature touch thee, drop a tear”. After looking at the tomb I turned to look at the church and found that nature was indeed watching over Hogarth’s tomb:

The River Thames is very close to the church and on the side of the churchyard wall is a plaque recording one of the floods when the Thames overflowed the very shallow banks along this part of the river.

View from the side of the churchyard wall looking down towards the Thames. Hogarth would have known this part of the river very well.

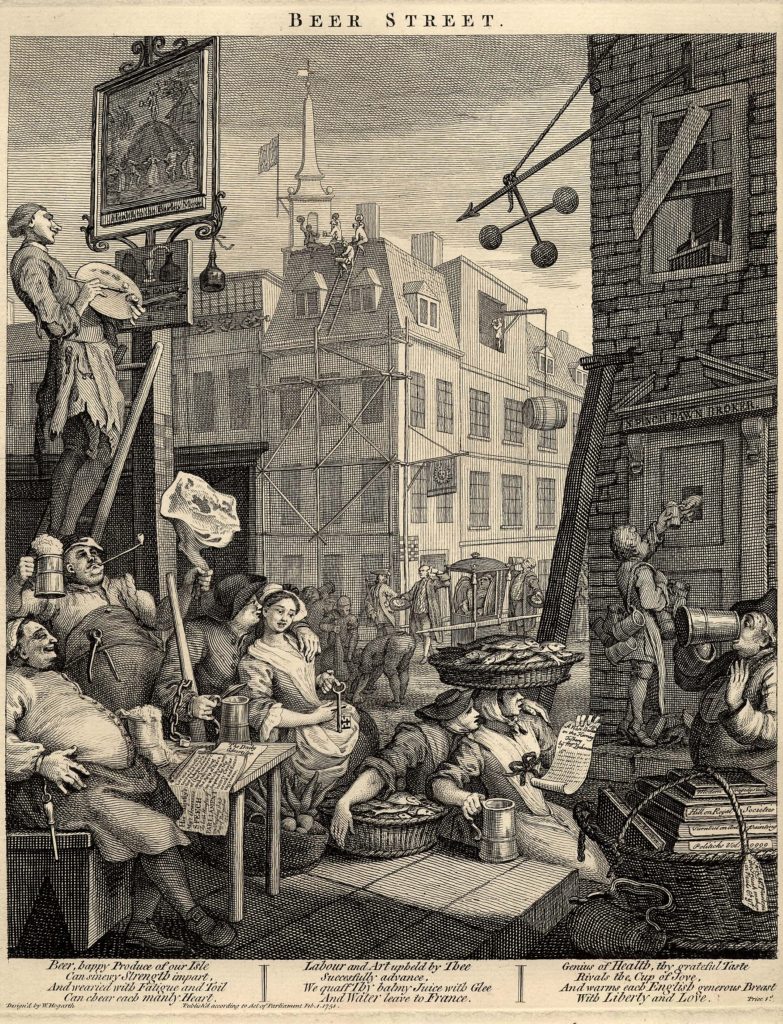

Some examples of Hogarth’s work (all ©Trustees of the British Museum). Here is Beer Street, a companion print to the famous Gin Lane. Beer Street is probably not so well-known as the scene is a more positive image than Gin Lane. Beer Street shows a happy, healthy and industrious population, all as a result of drinking beer.

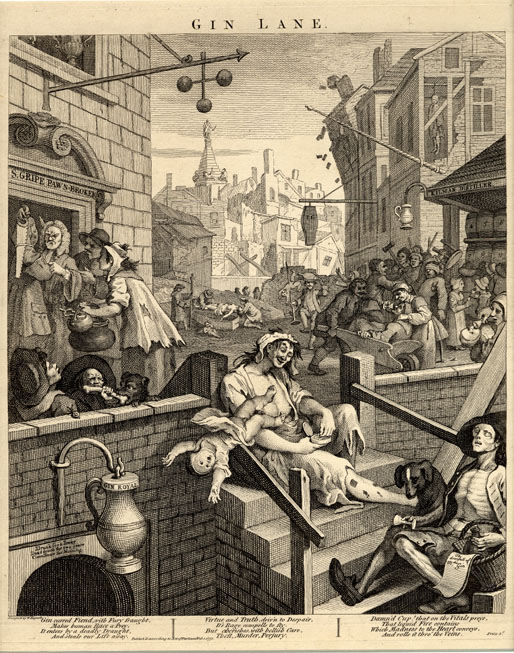

Whilst Gin Lane shows the dreadful effects on society of drinking Gin. Mother’s dropping their babies, a suicide hanging in the upper floor of the building on the right, the decay of buildings and general chaos on the streets. It was estimated that by 1743 the average consumption of gin was 2.2 gallons per person each year. The Gin Act came into force in 1751 to try to control the epidemic of gin drinking and Hogarth’s prints added to the impact of the campaign.

The following print is titled “A representation of the March of the Guards towards Scotland in the Year 1745”, also known as the March of the Guards to Finchley. The print is a fictional representation of the assembly of Guards at Tottenham Court Road on their way to Finchley to defend London from the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745.

The following print is the first from a set of eight titled “The Progress of a Rake”. These prints tell the story of Tom Rakewell from the first print where he comes into the possession of his father’s inheritance, through to the final print where we find Tom having descended into Madness and in the Bethlam Hospital.

Tom’s journey from his inheritance is then covered by a series of prints titled The Levee (his rise in society), The Orgy (the descent begins), The Arrest (the party ends), The Marriage (Tom’s desperate sham), The Gaming House (Tom loses everything), The Prison (the beginning of Tom’s end) and finally The Madhouse (the end of the line).

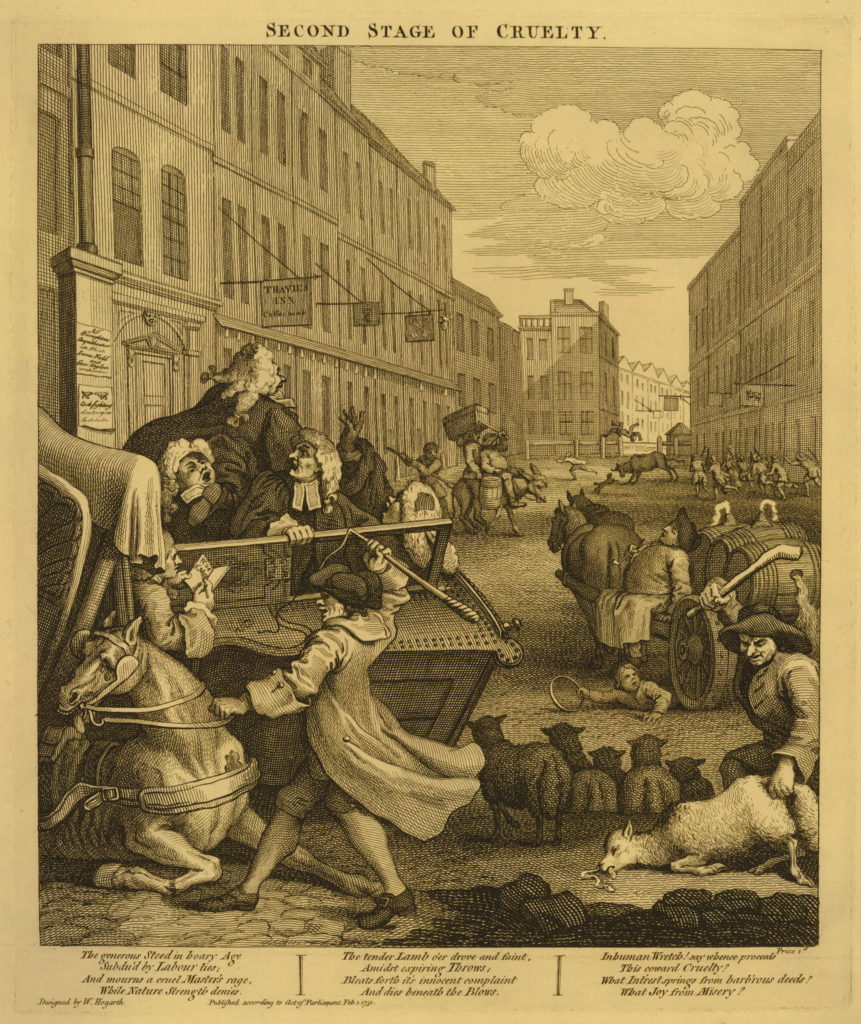

Hogarth hated the abuse of animals that was so common in the 18th century. A series of four prints told a story of the Four Stages of Cruelty. As with the Progress of a Rake, these four prints also documented a journey and argued that if children were cruel to animals, and this was not prevented by society, they would grow into cruel adults.

The first stage of cruelty introduces Tom Nero as the central character who, along with other youths on the streets, is being cruel to a wide variety of animals. In the second stage (shown below) Tom Nero is now savagely beating his horse after the animal has collapsed under the weight of the cart.

In the third stage of cruelty, Tom Nero has progressed from cruelty to animals to highway robbery and is shown after committing a murder. In the final print from the series titled “The Reward of Cruelty”, Tom has been executed at Tyburn and his body is shown being dissected for the purpose of the study of anatomy.

The four stages of cruelty are a shocking series of prints, and probably do show the horrific level of cruelty that would have been seen on the streets of London during the 18th Century.

I find Hogarth’s work fascinating. Whilst his work was certainly exaggerated somewhat for effect, it does provide an insight into 18th Century society without the romantic haze of looking back over a couple of hundred years. Life then could be hard and cruel.

A visit to Hogarth’s House is well worth a journey to Chiswick.