I was in the Hague for my last post, and before leaving I wanted to visit a site in a suburb of the Hague that has a very direct and tragic connection with London.

London had been under fire from V-1 flying bombs starting in June 1944 until October 1944 when the launch sites were captured as the allied forces progressed through France and Belgium.

In September 1944 a new weapon was first used against London. This was the V-2 rocket which had a much more flexible launch method than the V-1 and also longer range so launching against London was possible from the areas still held by German forces.

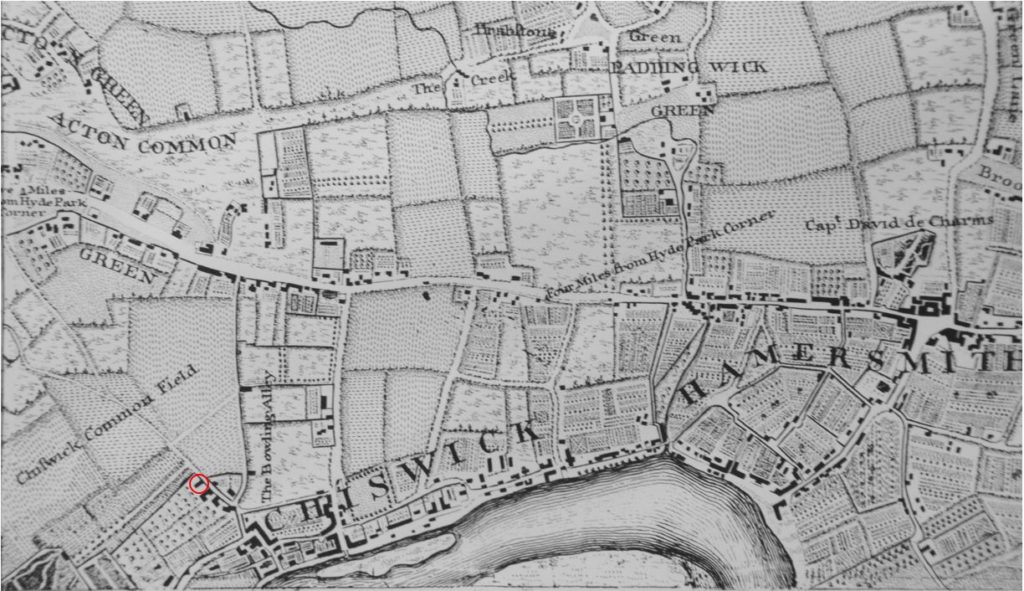

Although Allied forces were pressing up from the Belgium border, through Eindhoven and Nijmegen, the coastal west of the Netherlands was still under German control and the area around the Hague offered the ideal location to launch against London. The Hague had the rail connections to bring in the rockets and their fuel, and the suburbs of the Hague offered a large wooded area, crisscrossed by small roads which provided the perfect cover for mobile launches.

The V-2 was a highly sophisticated weapon. The supporting infrastructure allowed the rocket to be launched from a mobile launcher with fueling carried out on site along with final setting of the gyros that would guide the rocket to its destination. The speed of the rocket meant that it was almost impossible to destroy whilst in flight. The trajectory for the rocket was a parabola from the launch site up to the edge of space before descending at up to three times the speed of sound to the weapon’s target.

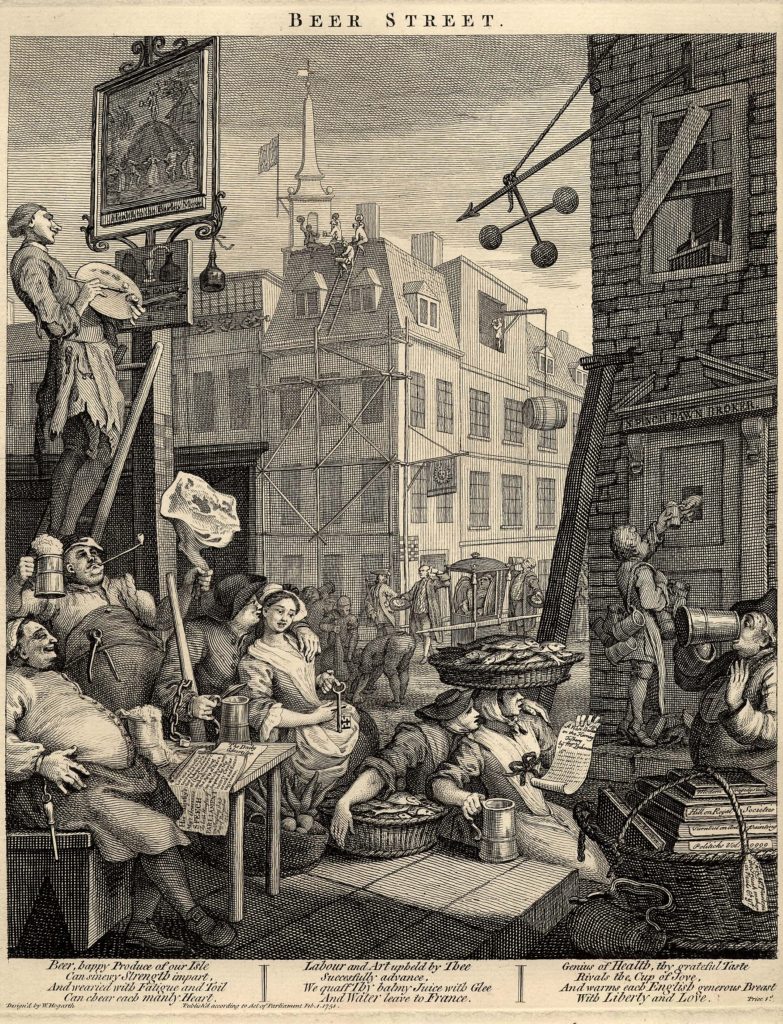

The following photo shows a V-2 rocket on a launch platform. Most photos of the V-2 show the black and white painted rocket, these were the test versions and the painted colour scheme ensured that any rotation of the rocket could be identified during flight. In use, the rockets did not have a colour scheme.

Black and white (CL 3405) V2 on launching platform Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205087580

Wassenaar is a suburb of the Hague, located to the north east of the city. It is a wooded area with small roads crossing the area, concealed under trees which also line the roads. Wassenaar was one of the main launch sites for V-2s and the first rockets against London were launched from Wassenaar’s roads.

Before leaving the Hague, I wanted to find the location of the first V-2 launch against London, so headed out on the short drive to Wassenaar.

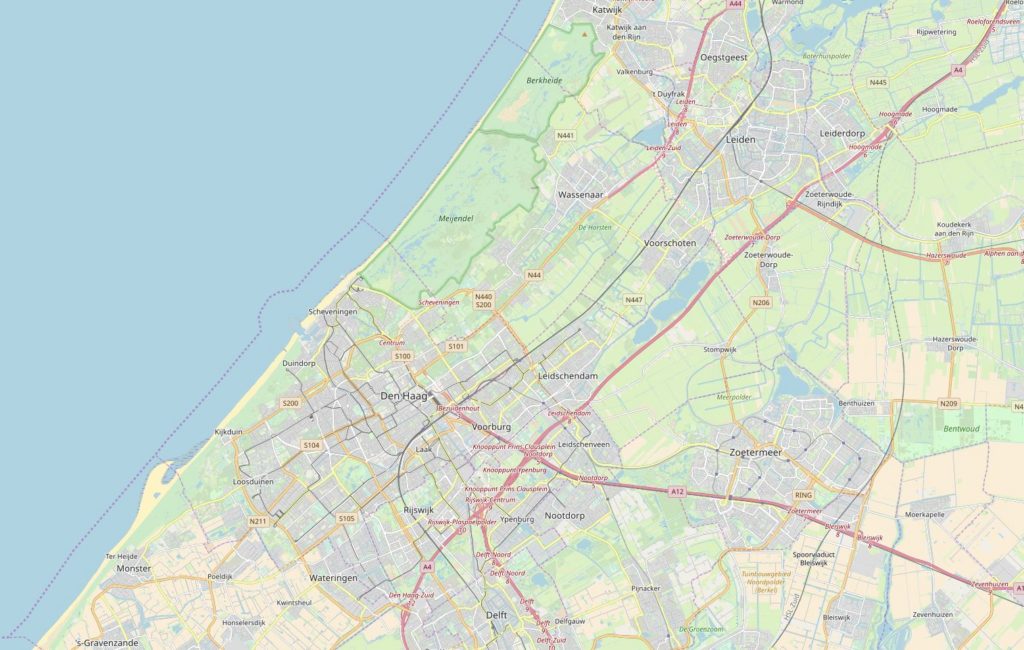

The following map shows the city of the Hague. Follow the orange road (the N44) that runs from the Hague to the north east and you will find Wassenaar.

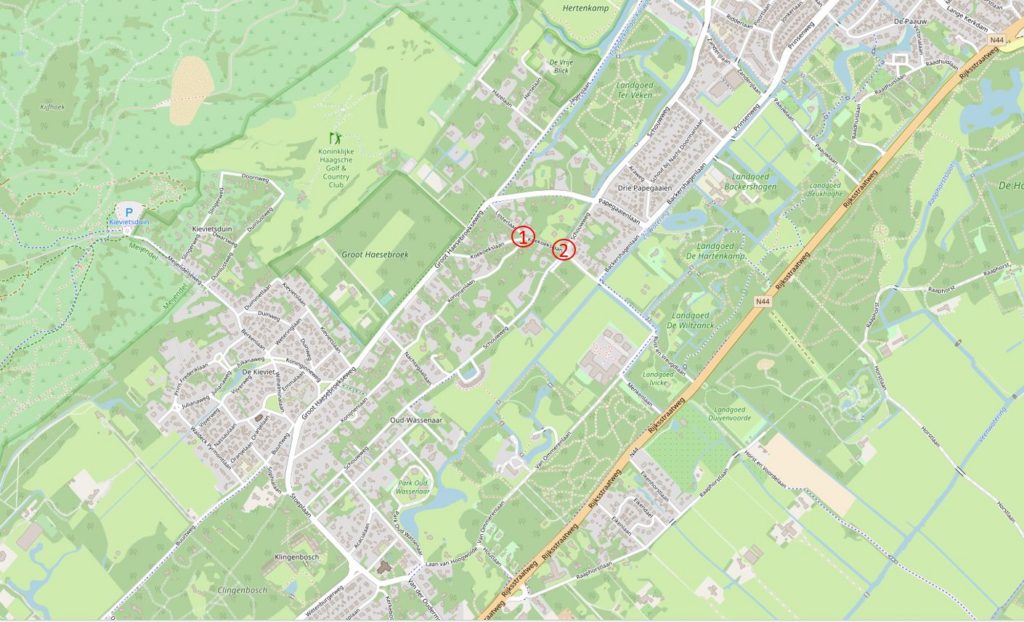

The following map extract shows Wassenaar in detail. The first launches against London took place on the evening of the 8th September 1944. There were two simultaneous launches at two different road junctions. These were ideal locations as road junctions offered a larger space for the rocket launcher and supporting vehicles as the rocket was fueled onsite. The map also shows the wooded nature of the site and that these were side roads – good concealment for the time needed to prepare and launch.

(The above two maps are “© OpenStreetMap contributors”).

At around 6:35 pm on the evening of the 8th September 1944, the residents of Wassenaar heard a loud roaring noise and saw two objects rising above the trees, slowly at first before quickly gathering speed, then rushing skyward.

One was from the junction of three roads shown as point 1 in the above map. This is the junction of Lijsterlaan, Konijnenlaan and Koekoekslaan. This is the view of the junction as I walked up to the site:

Looking down one of the roads leading of from the junction shows the narrowness of the roads and the tree cover. It has not changed that much since the rockets were being launched here and shows how good the area was for concealment.

The original V-1 had to be launched from a fixed launching ramp. As well as the technological development of the rocket, other innovations with the V-2 were mobility where the complete system comprising a mobile launcher, fuel tankers (including liquid oxygen), launch and control system could drive up to a new location and launch within about two hours.

The following illustration shows a V-2 rocket in launch position on its mobile transport and launch platform:

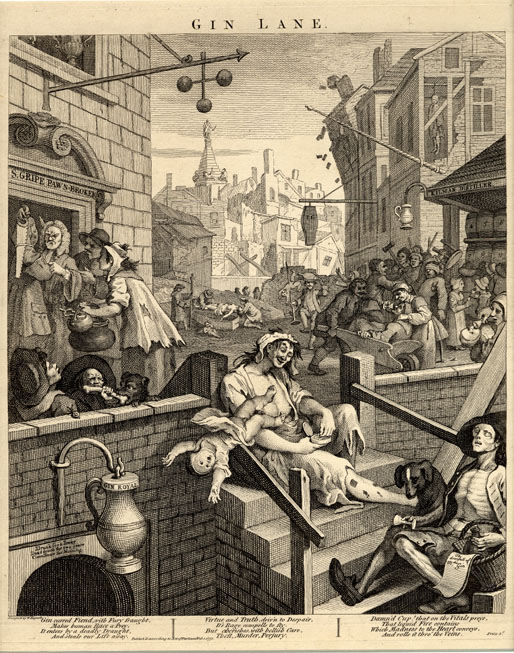

The following photo shows a V-2 just after the initial launch. Two of these being launched almost simultaneously from the wooded side roads of Wassenaar must have been a frightening sight for the local residents.

Black and white (CL 3429) German photograph of a V2 rocket in the initial stage of its flight Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205087577

This part of Wassenaar is occupied by large houses and grounds. Reports from immediately after the launch tell of the road surface been scorched and melted, with trees being burnt for a few feet above ground level where flame from the rockets engines must have bounced of the road and been deflected onto the adjacent trees.

On the next day, the 9th September, the RAF started bombing Wassenaar. A cat and mouse game ensued with rockets, fuel and launch equipment being stored across the area and mobile launches taking place on a regular basis, and the RAF trying to locate and bomb any V-2 related infrastructure that could be found.

Another view of the road junction.

If you look at the patch of grass on the right, there is a white painted stone. Look to the upper right of the white stone, and just to the left of the tree is a small, wooden pillar.

The pillar records the junction as being the site of the first launch of a V-2 rocket on the 8th September 1944:

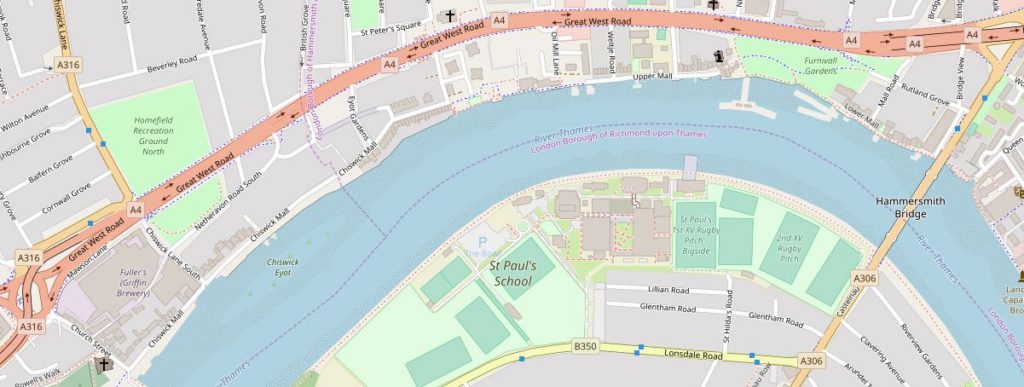

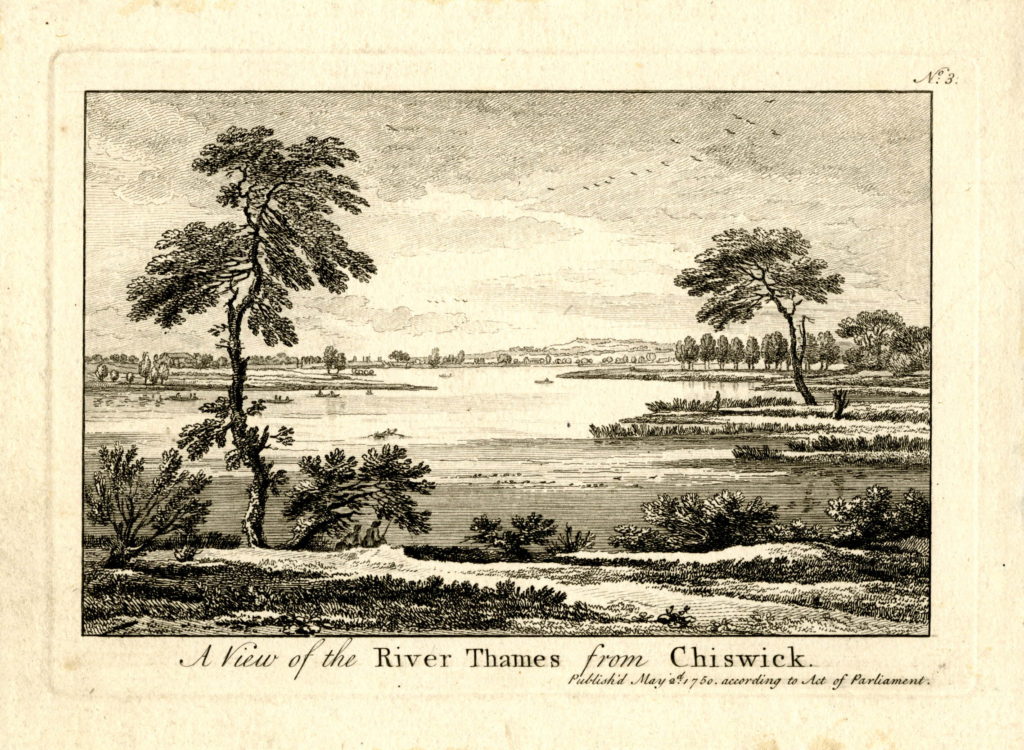

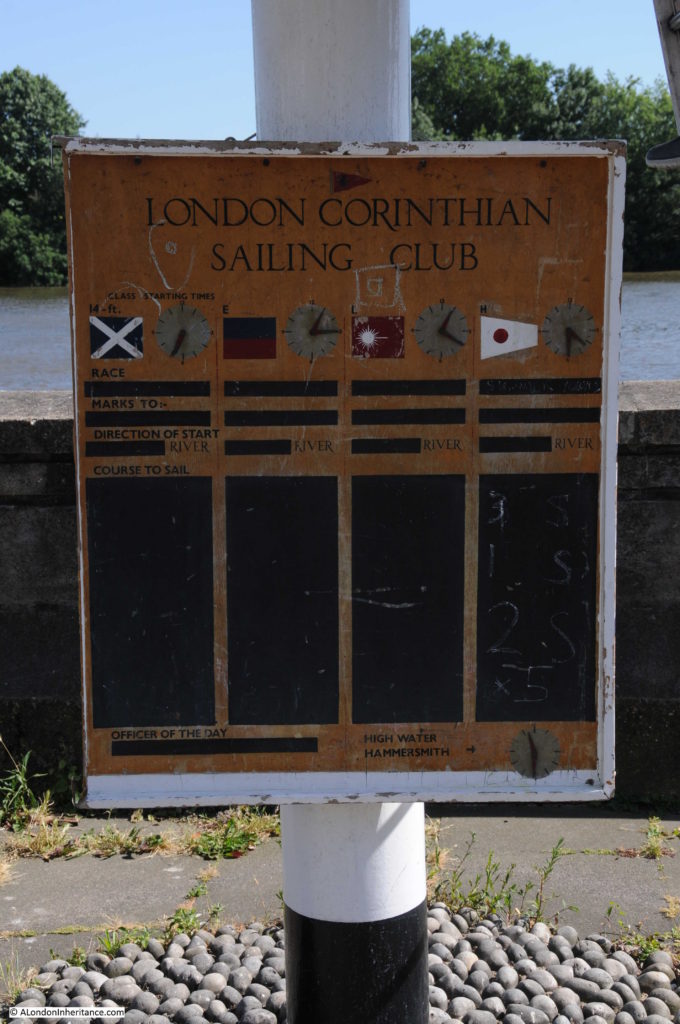

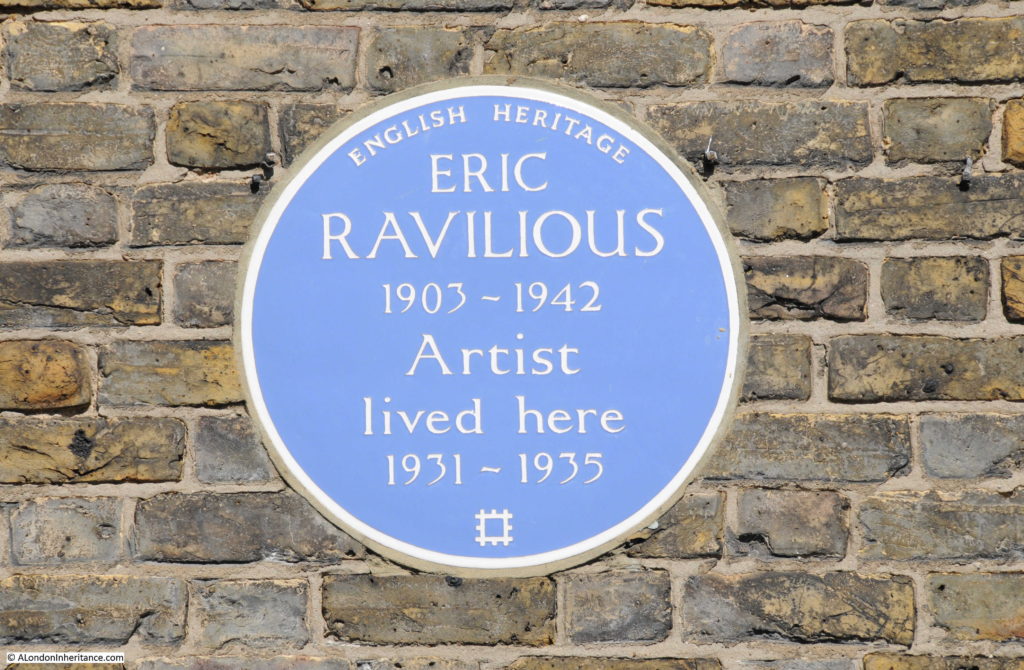

Soon after returning from the Netherlands, and on the 8th September 2018, I visited the site where the V-2 launched from Wassenaar landed – in Staveley Road, Chiswick where another pillar can be found recording that the first V-2 fell here. It had taken the rocket around 5 minutes to get from Wassenaar to Chiswick.

The view looking along the street from in front of the memorial pillar:

The memorial pillar is in front of a small electrical substation:

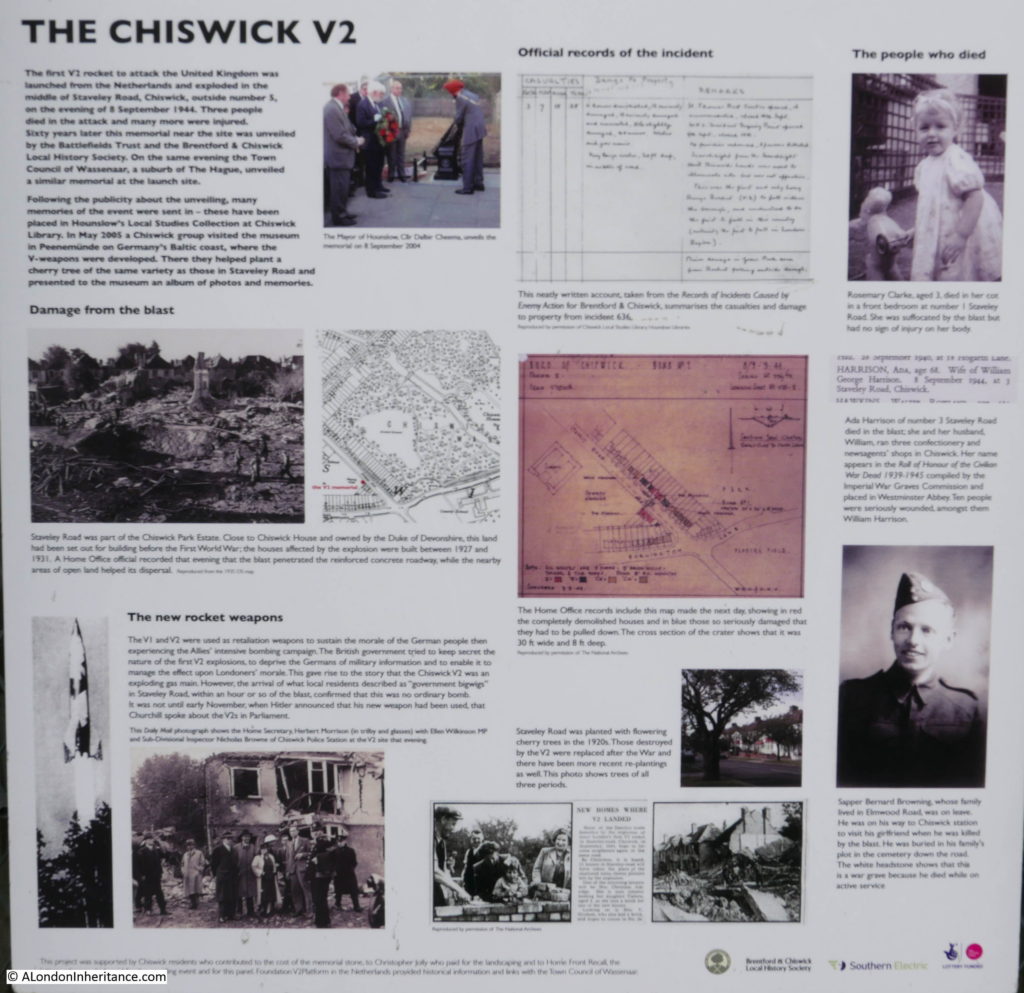

To the right of the pillar, mounted on the fence is an information panel which was unveiled by the Battlefields Trust and the Brentford and Chiswick Local History Society, on the same day that the pillar in Wassenaar was also unveiled.

The V-2 on Chiswick resulted in three deaths. Three year old Rosemary Clarke who lived at number 1 Staveley Road, Ada Harrison aged 68 of 3 Staveley Road and Sapper Bernard Browning, who was on leave, and on his way to Chiswick Station.

Destruction was considerable. The V-2 blew a crater 30 ft wide and 8 ft deep at the point of impact. The following panoramic photo from the Imperial War Museum archive shows the damage that a V-2 could inflict.

V1 AND V2 DAMAGE, 1944-45 (HU 66194) ‘Extensive damage caused by mystery explosion in Southern England.’ The photograph actually shows the site of the first V2 rocket impact on Britain, Staveley Road, Chiswick. Photograph taken 9 September 1944. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205070209

There was a second V-2 rocket launched at the same time, a very short distance from the location described above. This V-2 was launched from the point marked 2 in the map, at the junction of Lijsterlaan and Schouwweg. This V-2 would land minutes later at Parndon Wood, near Epping. Due to the rural nature of this location there were no casualties.

The following photo shows the junction from where this second V-2 was launched:

From the 8th September onward, there was a continuous series of V-2 launches from Wassenaar and the Hague. The area was also used for storage of rockets and fuel, launching equipment and the German forces and command structure that would launch the rockets were also housed in the surroundings of Wassenaar and the Hague.

Allied planes flew many missions over the area trying to locate and destroy V-2 infrastructure. On the 3rd March 1945 a large force of bombers mounted an attack on the forested regions of the Hague, but due to navigation errors many of the bombs fell on the Bezuidenhout suburb resulting in a large loss of life in the Dutch population.

The Dutch population also suffered when rockets misfired, and also the disruption and treatment they suffered from living in and around a place that was used to store, transport, prepare and launch such an intensive rocket programme.

One of the locations where V-2 rockets were checked and prepared was the tram depot in Scheveningen, the coastal suburb of the Hague.

This is the view of the tram depot today:

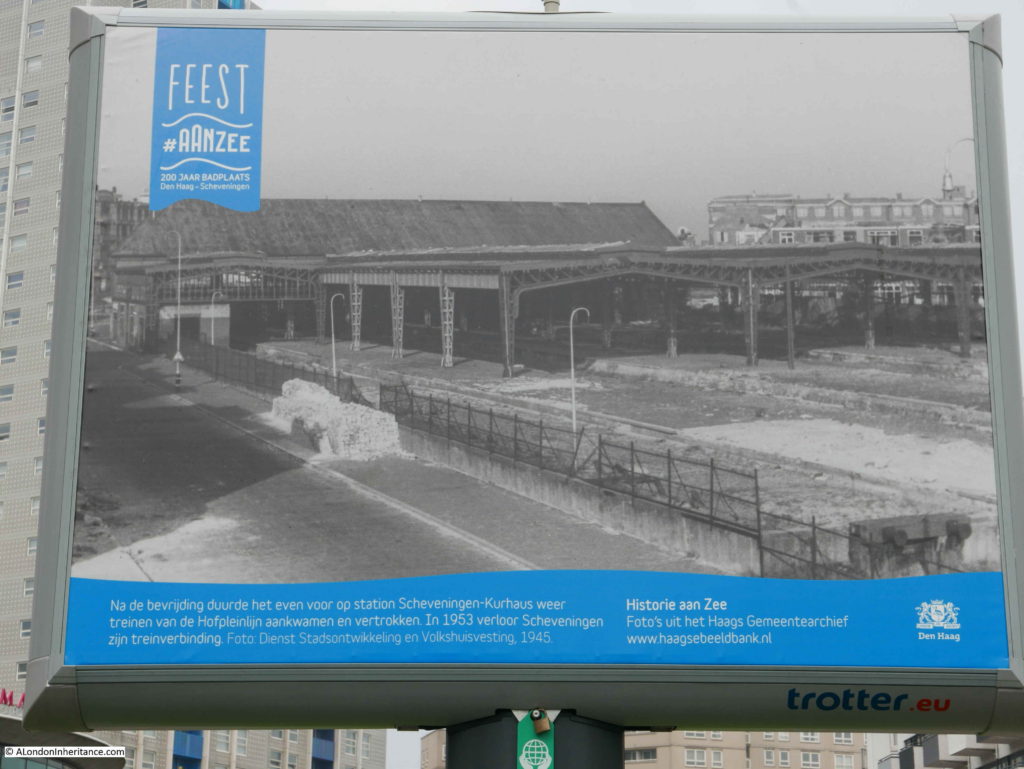

There are historical posters around the streets commemorating the 200th anniversary of Scheveingen as a seaside resort. One of these posters shows the state of the tram depot in 1945:

The text states that after the liberation, it took some time for trams from the Hofplein line to return to Scheveningen-Kurhaus station and that the tram connection was finally reestablished in 1953.

On the 27th March 1945 the last V-2 was launched against London. It fell on Orpington in Kent resulting in the deaths of 23 people. Whilst the west of the Netherlands was still occupied, rail connection with the rest of Germany had been cut and the German rocket forces had already been withdrawn from the Hague in order to avoid capture of the personnel and their equipment.

From the first V-2 on the 8th of September to the last on the 27th March, a total of 3172 V-2 rockets were launched. Of these around 1358 fell on the greater London area.

London did not suffer as badly as Antwerp, An important port for the Allied forces allowing supplies to be delivered into Belgium rather than the French ports further south, around 1610 V-2 rockets were launched against Antwerp.

Other rockets landed in France, Maastricht in Holland and even in Remagen, Germany where the use of rockets were an attempt to try and disrupt US forces by targeting the Ludendorff Bridge across the Rhine. This was the first time that rockets had been used to attack a very specific target. Eleven rockets were fired at the bridge, however none hit their target, but American soldiers and German civilians were killed.

The V-2 campaign against London killed more than 6,000 people.

The rockets were constructed by slave labour and many tens of thousands died due to the appalling conditions in which they were held and laboured.

The impact of the V-1 and V-2 weapons was considerable on those forced to build them, the areas where they were launched and their targets.

Two pillars in two countries, roughly 205 miles apart provide a reminder of the devastation that these weapons would cause.