Do you ever wonder what happened to the contents of all the City churches that have disappeared over the centuries? Probably not, however this rather obscure interest took me recently from the Minories in the east of the City to a small village in deepest Hampshire.

The Minories is currently the name of a street leading from Tower Hill to Aldgate High Street. The name derives from the sisterhood of the “Sorores Minores” of the Order of St. Clare. The sisters of the order were known as Minoresses and their religious house as the Minories, and it was one of these houses or abbey that occupied the area to the east of the street currently known as Minories.

The abbey had an associated church, and following the dissolution, the church became the parish church and was known as the Church of Saint Trinity, or Holy Trinity in the Minories. It is the later name that was most commonly associated with the church.

Holy Trinity was located at the end of a street leading from the Minories. The street is currently called St. Clare Street (taking its name from the religious order).

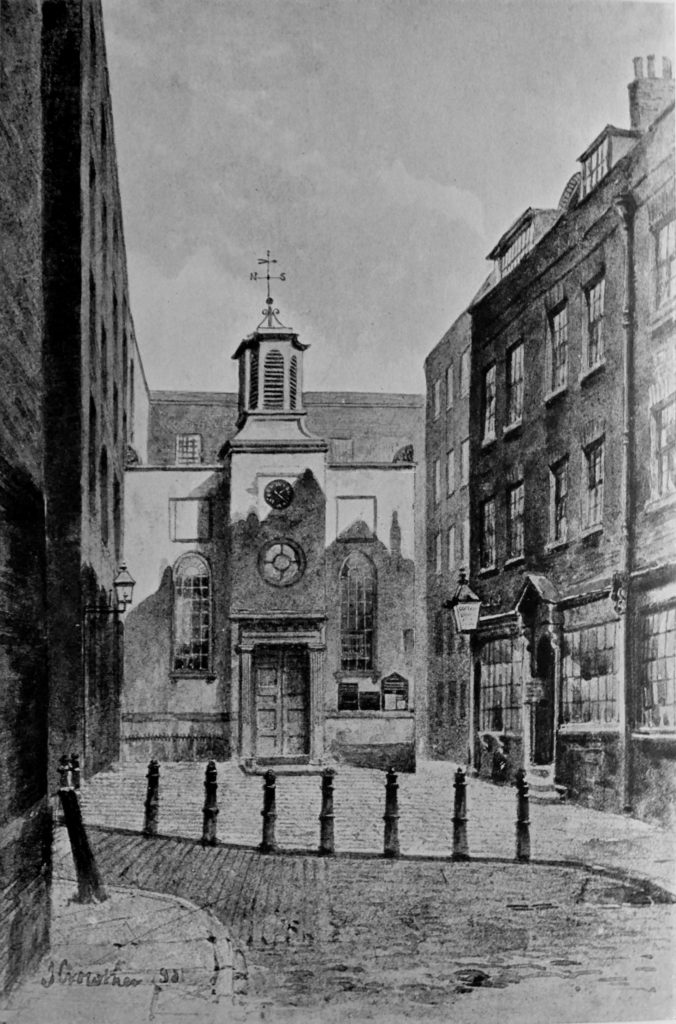

The book “A History of the Minories” written by a vicar of the church and published in 1922 provides a fascinating history of the abbey and the church. It also includes a drawing of the church at the end of the side street leading from the Minories.

This is the same view today. The church was at the end of the street, with the front of the church just in front of the building that terminates the end of the street.

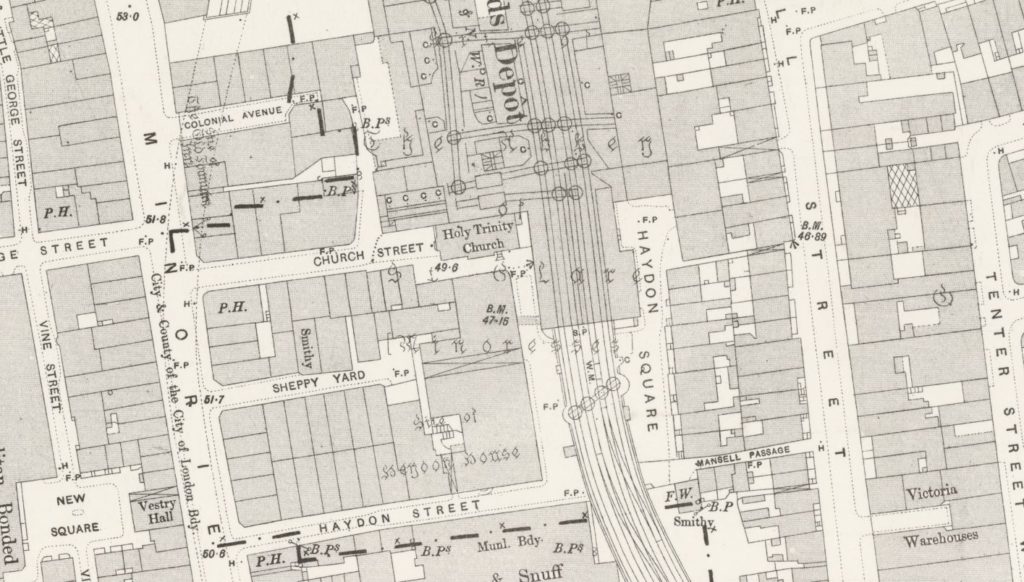

The 1895 Ordnance Survey map shows the location of the church, in the centre of the following map extract, at the end of what was then Church Street (now St. Clare Street).

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

A map of the same area today. I have marked where the church was located by a red rectangle (© OpenStreetMap contributors) .

You will see on the 1895 map that there is a public house on the southern corner where Church Street meets the Minories. The building is still a pub – The Three Lords:

The current pub building dates from around 1890, however a pub with the same name has been on the site for much longer. The earliest newspaper reference I could find to The Three Lords dates to the 11th January 1819 when the Evening Mail reported on the arrest of a man for robbery. He was formerly a respectable man with carriage and servants, one of whom in 1819 kept the Three Lords and a pot from the pub was found in the room of the alleged thief.

The view from the far end of St. Clare Street looking back towards the Minories. The street is still cobbled.

Holy Trinity church was closed in 1899. One of the closures of City churches under the Union of Benefices Act of 1860 where churches were closed and their parish amalgamated with another parish (St. Botolph’s Aldgate for Holy Trinity).

Closure of churches was a very controversial act for the Vicars of the churches involved along with their parishioners. There is an interesting letter in the London Evening Standard on the 30th May 1893 from the Vicar of Holy Trinity. The letter addresses errors about the history of the church in an earlier article, and demonstrates the passion resulting from the way in which the closure was managed. It is a long letter, but provides some fascinating insight into a small parish at the end of the 19th century. It also demonstrates the interest of a parish vicar in their church. Frequently the image of the Vicar is of a remote character, mainly interested in the income that could be generated from the role.

The letter reads:

“HOLY TRINITY CHURCH, MINORIES – Under the above title an article has gone round the papers purporting to give particulars of my church and its past history, some extracts of which appeared in your Morning and Evening Editions of the 25th instant. Will you permit me, then, to say that none of the statements in that article are correct.

In the first place, the name of my church is not ‘St. Mary in the Minories’ but Holy Trinity, Minories. Secondly, the mummified head which we have could not be that of the Duke of Norfolk, as the writer states, for that nobleman never had anything to do with the abbey or the church that I am aware of; but it may be the head of the Duke of Suffolk, to whom the abbey was given for a residence, by Royal letters patent, in the reign of Edward VI, and who, whilst resident there, was beheaded for attempting to place his daughter, Lady Jane Grey, upon the throne. The head was found in 1853 in one of the vaults, in a box of oaken sawdust, which, acting as an antiseptic, has marvelously preserved the skin of the face.

(The book “A History of the Minories” includes a rather gruesome photo of the mummified head)

Thirdly, the writer says that ‘the ancient Priory of Holy Trinity was founded by Matilda, Queen of Henry I, in 1108 whereas we know that the abbey (not priory) and its church was built in 1293 by Queen Blanche, widow of Henry le Gros, King of Navarre, who afterwards married Edmund, Earl of Lancaster. The arms of the Queen, with those of the Earl of Lancaster, are now in our vestry.

Fourthly, the writer states that on ‘the dissolution of monasteries by Henry VIII, the priory and its precincts were given to Thomas Audley, Lord Chancellor of England, who after pulling down the church, made the place his residence until his death in the year 1554’. These mistakes are even worse than the former ones, for Henry VIII gave the abbey to the Bishop of Bath and Wells (Dr. John Clerk) for a place of residence, where he died and was buried in the vaults of our church, though afterwards his body was, for some cause, removed to Aldgate Church. This was the man, who took to the Pope of Rome a copy of King Henry’s book against Luther, which led to that Sovereign receiving the title of ‘Defender of the Faith’, still used, though with a very different meaning.

The church was not pulled down on the dissolution of the abbey, but remained until 1706, when, being in a very dilapidated state, it was taken down and rebuilt from the ground with the exception of the north wall, upon which the chief monuments are placed.

Then the writer says that the parishioners of St. Katherine Cree, in 1622, obtained leave of Charles I to rebuild the priory church with the assistance of Lord Mayor Barkham.

From this it is quite evident that the writer of the article has mixed up our church and the abbey with another church and some priory. What in the world could see the parishioners of St. Katherine Cree have to do with Holy Trinity, Minories? Also, as the church was not rebuilt until 1706, Lord Mayor Barkham certainly did not assist to rebuild it in 1622, but Sir William Pritchard, who was Lord Mayor in 1683, purchased the abbey, and resided in it during his mayoralty, calling it, I believe, the Mansion House.

May I add that I was at first greatly opposed to the amalgamation of Holy Trinity, Minories, with St. Botolph Aldgate, and wrote a little history of the church in order to raise funds for its restoration, when the Charity Commissioners came down upon us and confiscated the church property devoted by the churchwardens to the maintenance of public worship, leaving them only thirteen pounds a year to pay the salaries of organist, pew-opener, bell-ringer, fire insurance, repairs, gas, coals, water, &c. ? Also they seized funds for giving every Christmas all the widows living in the parish five shillings, accompanied with coal and bread tickets.

This unrighteous impoverishment of the church led me to consent to the amalgamation scheme now about to take place, but I shall leave my parish and people with much regret.

I am, Sir, your obedient servant, Samuel Kinns, Vicar.”

I walked down St. Clare Street, to where the street takes a sharp right turn. In the following photo, the front of the church was just behind the gates, roughly in line with the red bin on the left.

Nearly all the buildings at this end of the street are relatively recent.

Holy Trinity, Minories closed as a church at the end of the 19th century, but the church survived as a parish hall until the Second World War when the building suffered severe bomb damage. A wall did remain until final clearance of the area in the late 1950s.

Taking the sharp right turn on St. Clare Street, in front of where the church was located, and there is one remaining building, an old warehouse that would have probably been around at the same time as the church.

Finally, getting to the theme of the post, does anything remain of the church?

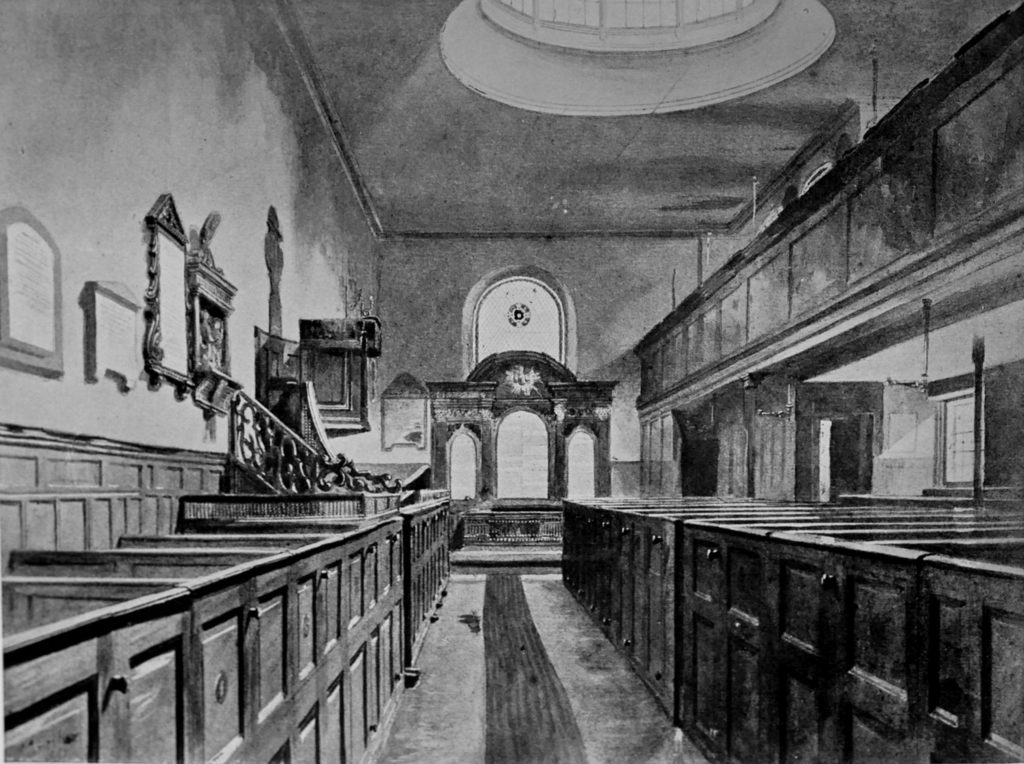

The following drawing of the interior of the church from the book “A History Of The Minories London”, shows a pulpit on the left, where the rows of pews end.

The pulpit can still be seen today, but in a very different location to the Minories.

The church was closed in 1899, and in 1906 the pulpit from Holy Trinity, Minories was presented to All Saints’ Church, East Meon in Hampshire.

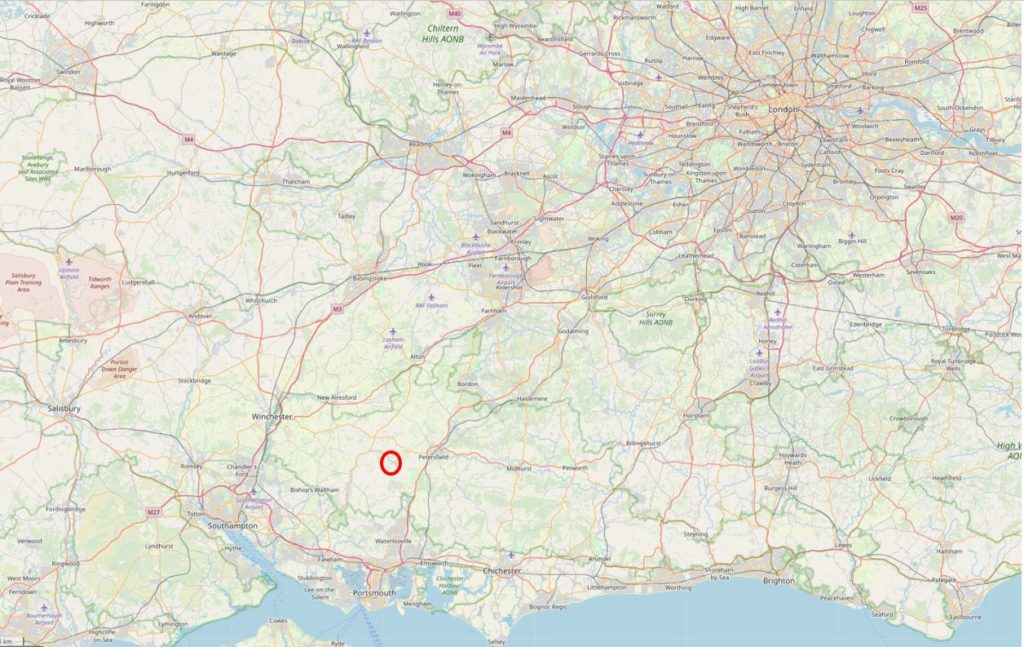

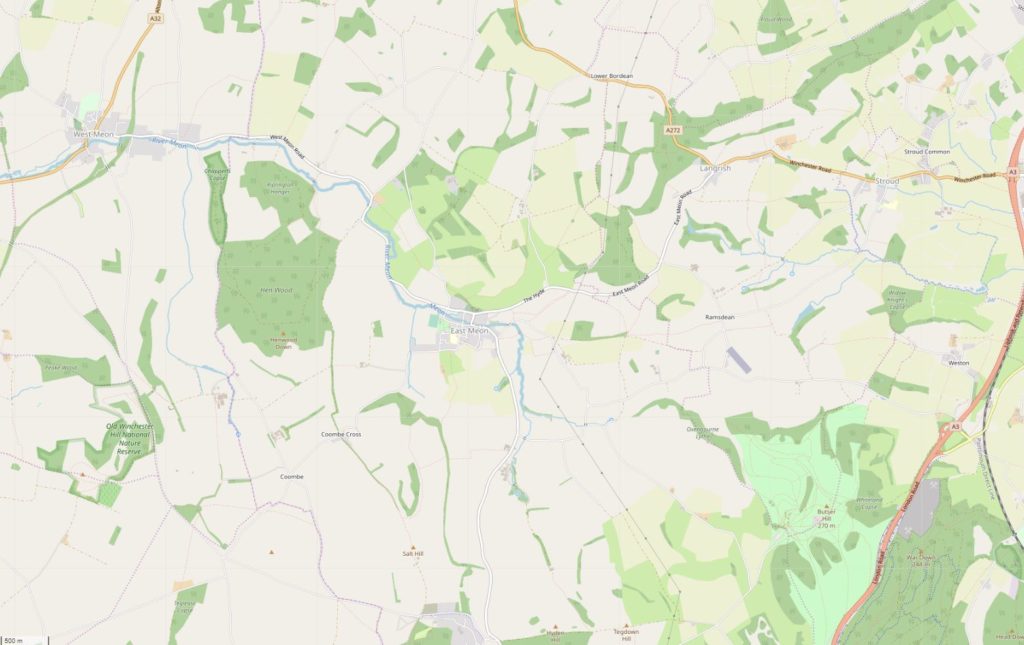

East Meon is a village in Hampshire, to the west of Petersfield in the South Downs. It is close to the source of the River Meon. In the following map extract, the location of the village is indicated by the red circle. (Maps © OpenStreetMap contributors)

Zooming in further and the following extract shows the village in the centre of the map, the River Meon flowing through the village, which is surrounded by countryside.

A couple of weeks ago, I headed out to East Meon to find Holy Trinity’s pulpit.

East Meon is best reached either via the A3, turning off near Petersfield, or from the A32 at West Meon. The final few miles of travel along either of these routes is along country lanes with very little traffic and the rolling hills of the South Downs on either side.

In the centre of the village is a finger post showing the nearest villages and towns and also signposting the village shop, school, village hall and car park.

The River Meon flows through the centre of the village.

The first view of All Saints’ Church, East Meon from the centre of the village. The church has a rather dramatic location, on raised ground overlooking the village, and with the towering Park Hill rising directly behind the church.

A closer view of the church.

The church was built between the years 1080 and 1150. Although with later renovations, repairs and changes, the layout of the church is the same cross-shaped design as when originally built. A central tower dominates over a nave, chancel and transepts which lead off either side from the base of the tower.

Major restoration was carried out during the early 20th century, and as part of this restoration, the Holy Trinity pulpit arrived in East Meon.

The main entrance porch to the church provides a superb view looking back over the village of East Meon.

On entering the church, the pulpit comes into view.

A close up view of the original Holy Trinity pulpit. At first sight, perhaps not very impressive, but it dates from 1706 and spent almost 200 years serving the parishioners of the Minories in the City.

This is the pulpit from which Edward Murray Tomlinson, the author of the book I have on my desk – A History of the Minories London – would have preached from during his time as a Vicar of Holy Trinity.

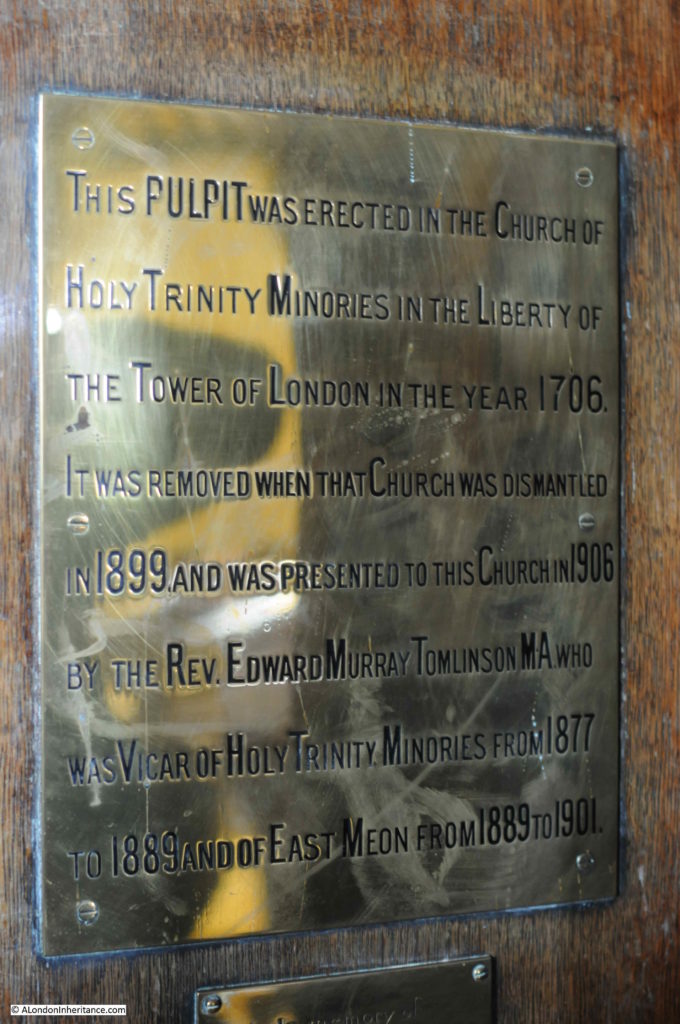

A brass plate on the door of the pulpit confirms the origin, and provides some background as to how the pulpit found its way from the Minories to East Meon.

The Rev. Edmund Murray Tomlinson who presented the pulpit to the church must have noticed a considerable difference between his 12 years as Vicar of Holy Trinity, Minories and his following 12 years as Vicar of East Meon.

The pulpit arrived at a time when the East Meon church was undergoing considerable renovation. The East Hampshire Chronicle on the 3rd November 1906 reported that the church had just reopened for public worship and that restoration had cost £1,130.

Restoration included major works such as the lowering of the floor to the original Norman level to reveal the “dignity of the massive Norman arches”. The article also references the arrival of the pulpit from Holy Trinity, Minories to confirm the facts given on the brass plate.

The interior of the church is fascinating, not just the architecture, but also the decoration and furniture of the church.

The church provides a home for the East Meon Millenium Embroidery. Started in 2002 and completed in 2008, the embroidery provides a wonderful snapshot of the village, created by local people. Unfortunately, no matter where I stood, I could not take a photo without a reflection in the glass.

Windows and Easter decorations:

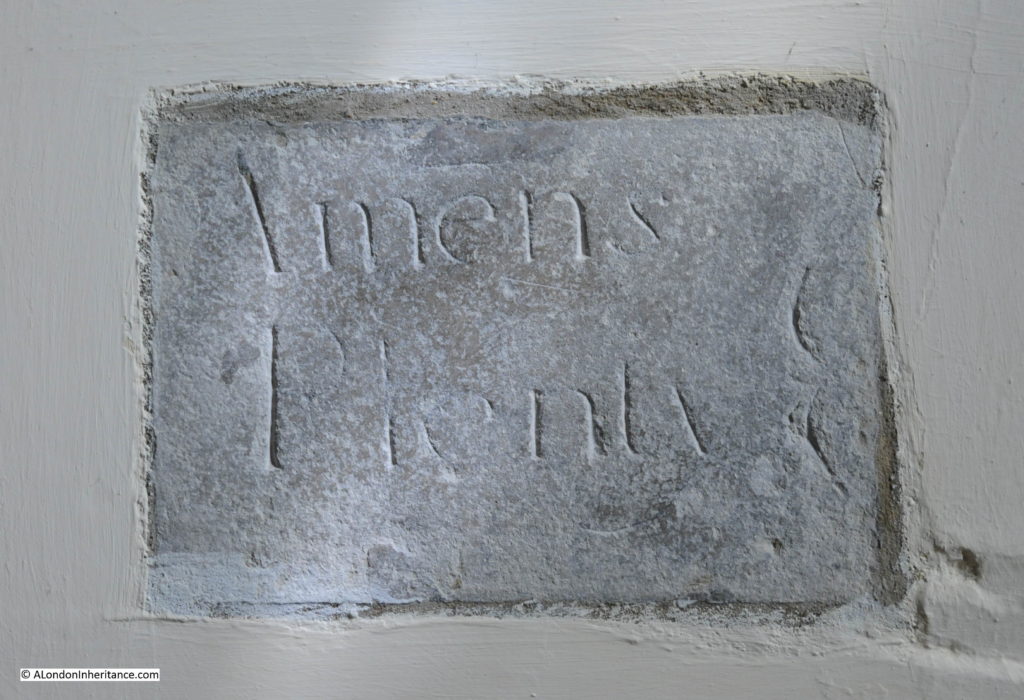

There is a strange stone set into one of the interior walls of the church. the words “Amens Plenty” inscribed.

The church guidebook provides an interesting local legend about the stone. It was lifted from the floor of the church in 1869 and underneath the stone was found the remains of four men. They were buried vertically which added to the mystery. The local legend is that they were four Parliamentary soldiers killed in the village before the Battle of Cheriton on the 29th March 1644. Cheriton is about 12 km to the north west of East Meon.

An interesting feature of the central tower is that access to the tower is via stairs up along the wall in one of the transepts, with a small balcony and doorway at the top of the stairs providing access to the tower.

Some very large capitals on the crossing arches that support the tower.

View along the central nave of the church with the Holy Trinity pulpit on the left at the end of the pews.

The church has two fonts. The first is a very plain stone font of unknown date. As with the Holy Trinity pulpit, churches seem to accumulate from other religious buildings and this font came from the ruined chapel of St. Nicholas near Westbury House in East Meon. Although being of unknown date, it looks very old.

The second font is much more ornate and has a more identifiable history. This is the Tournai font:

The font derives its name from the location of manufacture – Tournai in Belgium. It was delivered to the church in East Meon around the year 1150, and probably was a gift from Henry of Blois, the Bishop of Winchester. The fact that East Meon has such a font illustrates the importance of the church and village in the 12th century. There is another Tournai font in Winchester Cathedral.

The font is highly decorated, although this was rather difficult to photograph in the strong light streaming through the windows. Two sides of the font tell the story of Adam and Eve whilst the other two faces and the top of the font are covered in symbolic designs.

The following photo shows the west side of the font. The pillars are holding up the flat earth above which some rather strange monsters or dragons are carved.

The east side of the font relates part of the story of Adam and Eve. Rather difficult to see in the following photo, however the structure on the right is a representation of the Gates to Paradise. There is a figure to the left holding a large sword. The figure also has wings and is a representation of an angle who has expelled Adam and Eve from Paradise. Adam and Eve are to the left of the angel and are both trying to hold their fig leaves in place.

The font is a remarkable example of 12th century craftsmanship.

In the outside wall of the church, there are some gorgeous doors:

The central tower of the church. The spire dates from 1230 when the final additions were made to the church including the Lady Chapel and the south aisle.

Detail from the top of the tower. Wavy carving around the clock, open windows and along the wall of the tower.

The rear view of the church shown below includes the original chancel on the right, with the 1230 Lady Chapel on the left.

The straight line distance between the location of Holy Trinity, Minories and East Meon is not that far, only 88km, or 55 miles, but they are very different places and that difference must have been even more apparent in the 19th and early 20th centuries when the Vicar and Pulpit moved from the Minories to East Meon.

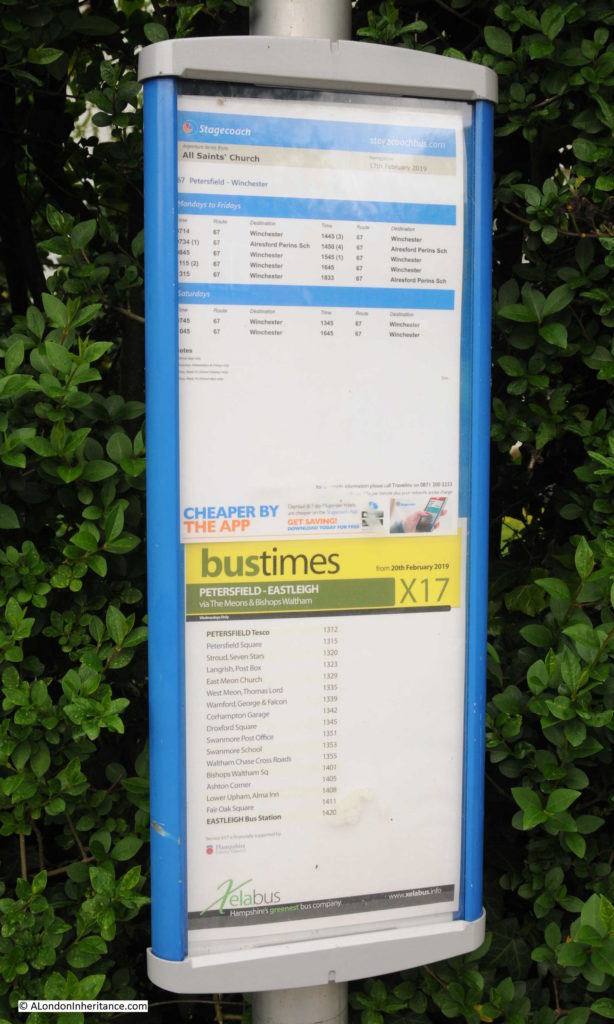

A modern day comparison of living in a village such as East Meon with living in the city is the difference in public transport. The bus stop timetable highlights the limited bus service to take residents to the nearest town.

Although the City still has a remarkable number of churches, so many have been lost over the years, from the Great Fire, the wave of late 19th century closures that included Holy Trinity, the Blitz and other occasional closures and parish amalgamation.

Church contents would have been lost through fire and bomb damage, but there must still have been a considerable amount sold or relocated to another church. The 1706 Holy Trinity pulpit is one item that can still be found, and continues to serve the same function as its makers intended over three hundred years ago.