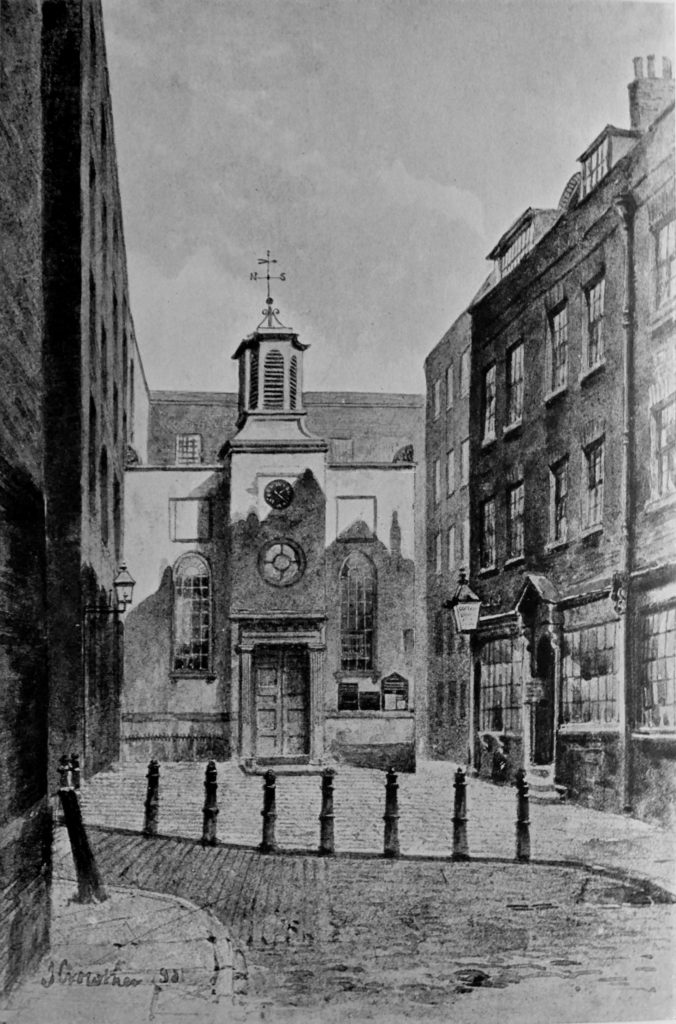

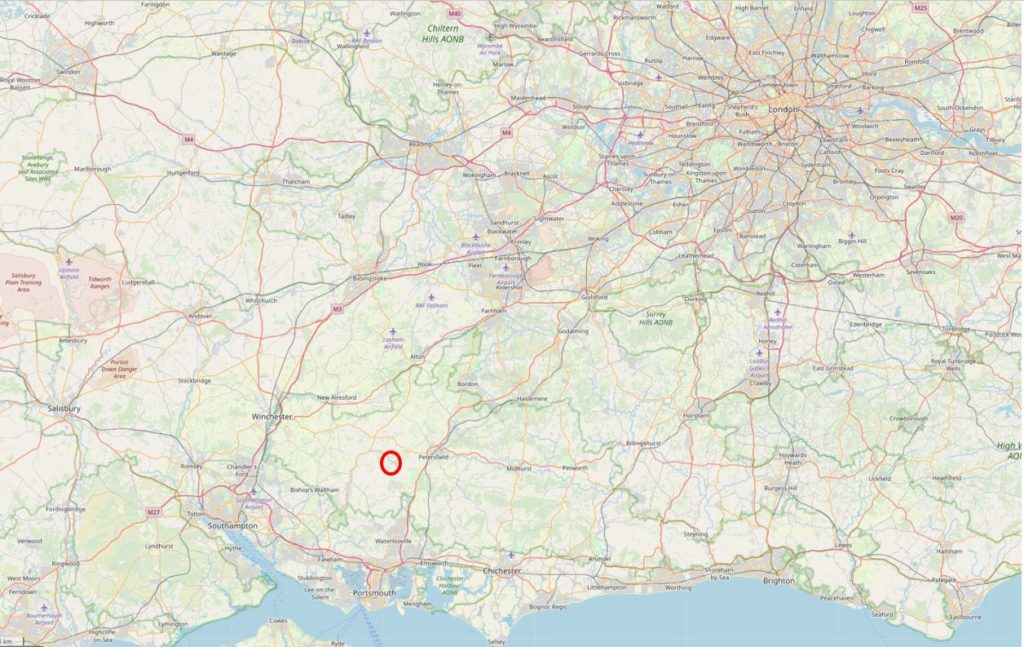

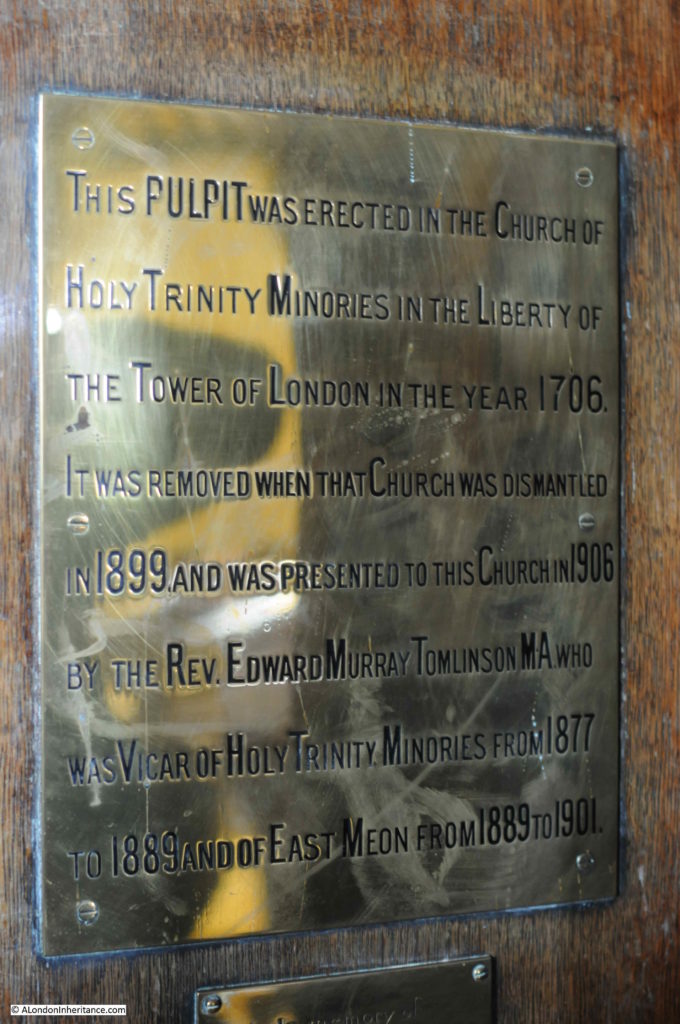

I have been to the Minories in a previous post when I explored the lost Church of Saint Trinity, or Holy Trinity in the Minories, and when I went to find the pulpit from the church which is now at All Saints’ Church, East Meon in Hampshire.

I wanted to return to explore the street, the abbey after which the street is named, and one of the most architecturally interesting buildings in the city.

The following photo is from Aldgate High Street at the northern end of the Minories, looking down the street.

The above photo shows what looks like an ordinary London street. Lined by commercial buildings, fast food stores, and the obligatory towers rising in the distance; the Minories has a far more interesting history than the above view suggests.

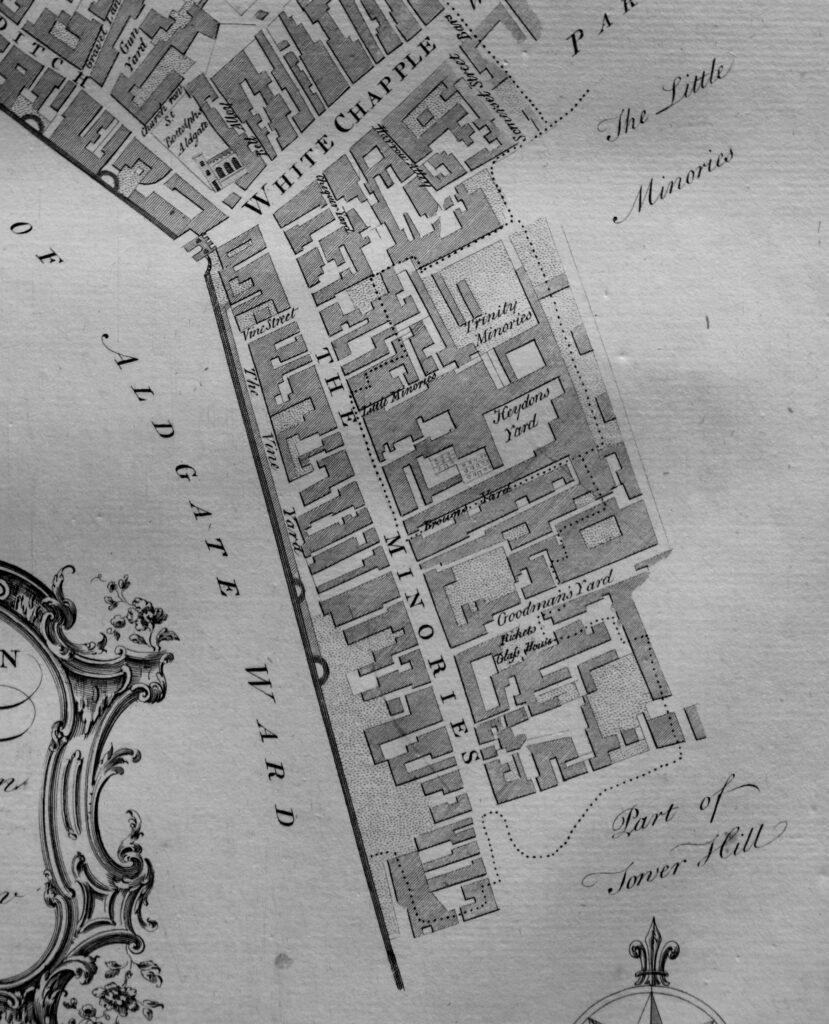

The following ward map from 1755 shows the Minories running down from Whitechapel, just outside the City wall.

In the above map, the area of land between the city wall and the Minories was once part of the ditch that ran alongside part of the walls. Look across the map at the top of the Minories, and running to the top left is another reminder of the ditch, the street Houndsditch, the last part of the name can be seen.

Being outside the City walls, the area may have been the site of a Roman cemetery, and in 1853 a large Roman Sarcophagus with a lead coffin was found near Trinity Church, just to the right of the street.

In the map the street is called The Minories, however today “The” has been dropped and the street name signs now name the street just Minories (I am continuing to use “the” in the post as I suspect it helps the text to flow”.

The name derives from the sisterhood of the “Sorores Minores” of the Order of St. Clare. The sisters of the order were known as Minoresses and the book “A History of the Minories, London”, published in 1922 and written by Edward Murray Tomlinson, once Vicar of Holy Trinity Minories, provides some background as to the origins of the order:

“The Order of the Sorores Minores, to which the abbey of the Minores in London belonged, was founded by St Clara of Assisi in Italy, and claimed Palm Sunday, March 18th 1212, as the date of its origin”.

The Order’s arrival in London, and establishing an abbey outside of the City walls dates back to 1293. It appears that the first members of the Order in the Minories came from another of the Order’s establishments just outside Paris.

The land occupied by the 13th century Order can be seen in the following map, enclosed by the red lines to the right of the street (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

The land supported a Church, Refectory, Guest House, Friars Hall, and along the right hand wall, a Cemetary and Gardens.

The Order received a number of endowments, and rents on properties that had come into their possession, and by 1524 they were receiving £171 per annum.

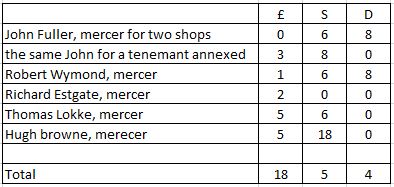

The lists of rents received in 1524 provide an interesting view of the costs of renting in different parts of the city. The following table lists the rents received from Hosyer Lane (now Hosier Lane in West Smithfield).

The majority of documentation that survives from the Order are mainly those relating to endowments, rents received, legal and religious documents. There is very little that provides any information on day to day life in the Minories. The only time we have a view of the number of sisters who were part of the Order, is at the very end of the Order, when on November 30th 1538, the Abbey buildings and land in the Minories were surrendered to Henry VIII.

The Abbess of the Order probably realised what was happening to the religious establishments in the country, and that by surrendering to the King, the members of the Order would be able to receive a pension, and it is the pension list that provides the only view of the numbers within the Order.

In 1538 there was an Abbess (Elizabeth Salvage) who would receive a pension of £40, along with 24 sisters, ranging in age from 24 to 76, and each receiving a pension of between £1 6s 8d and £3 6s 8d.

There were six lay sisters who do not appear to have received a pension – the name of one of the lay sisters was Julyan Heron the Ideote, indicative of how even religious establishments treated people who probably had learning difficulties.

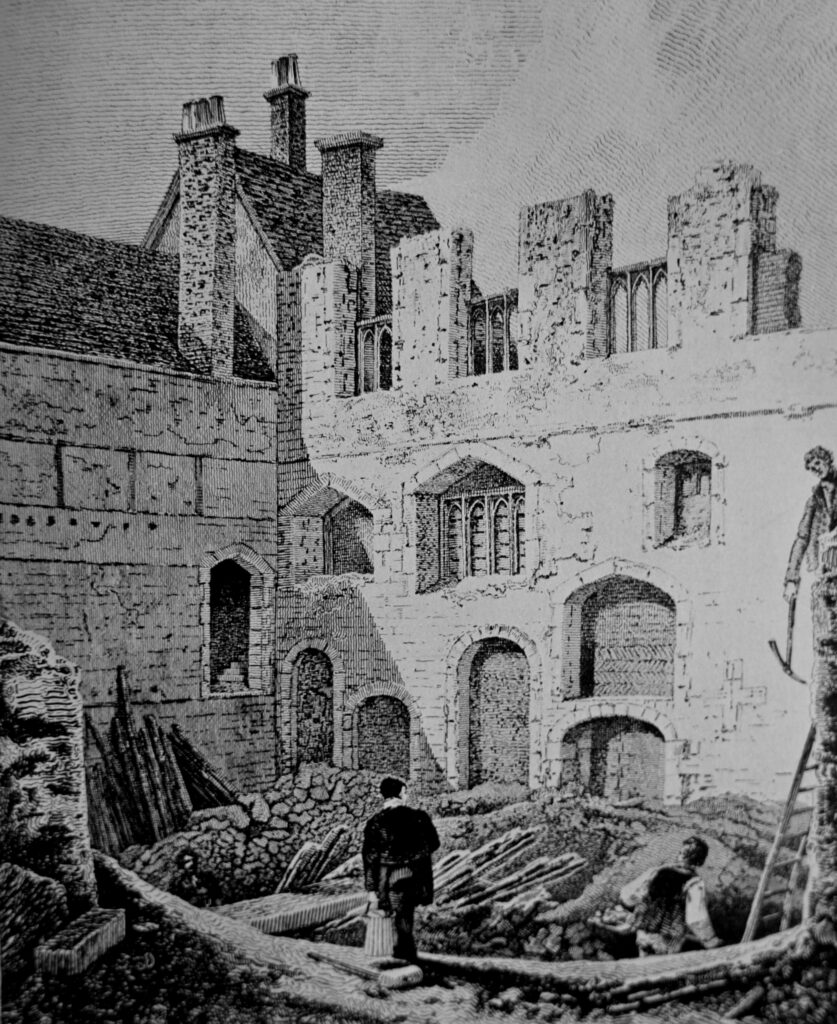

It appears that the King granted the land and buildings to the Bishop of Bath and Wells, and many of the original Abbey buildings were still standing in 1797, when a large fire destroyed many of the remaining buildings of the Abbey. The last religious building on the site was the church of Holy Trinity, which closed as a church at the end of the 19th century, but the church survived as a parish hall until the Second World War when the building suffered severe bomb damage. A wall did remain until final clearance of the area in the late 1950s.

The remaining abbey buildings of the Minories in 1796:

As well as the name of the street, Minories, a side street also recalls the order. The street in the following photo is St Clare Street, after the Order of St. Clare. It runs through the land of the old abbey, and at the end of the street was the church of Holy Trinity.

The pub on the corner of the Minories and St Clare Street is The Three Lords. The current pub building dates from around 1890, however a pub with the same name has been on the site for much longer. The earliest newspaper reference I could find to The Three Lords dates to the 11th January 1819 when the Evening Mail reported on the arrest of a man for robbery. He was formerly a respectable man with carriage and servants, one of whom in 1819 kept the Three Lords and a pot from the pub was found in the room of the alleged thief.

Walk along the Minories today, and apart from the street name, there is nothing to suggest that this was once the site of the Abbey. The street is mainly lined with buildings from the first half of the 20th century.

With a mix of different architectural styles and construction materials.

Towards the southern end of the Minories is one of the most architectually fascinating buildings in the city. This is Ibex House:

Ibex House was built between 1933 and 1937 and was designed as a “Modernistic” style office block by the architects Fuller, Hall and Foulsham.

it is Grade II listed and the Historic England listing provides the following description: “Continuous horizontal window bands, with metal glazing bars. Vertical emphasis in centre of each facade in form of curved glazing (in main block) and black faience strips”.

“faience” was not a word I had heard before, and the best definition I could find seems to be as a glazed ceramic. Black faience is used for the ground floor and vertical bands, with buff faience used for the horizontal bands on the floors above ground.

The ground floor, facing onto the Minories consists of the main entrance, sandwich bar and a pub, the Peacock:

The Peacock is a good example of the way developers have integrated a business that was demolished to make way for a new building, in that new building.

A pub with the same name had been at the same location since at least the mid 18th century. It was demolished to make way for the Ibex building, and a new version was built as part of the development.

An 1823 sale advert for the Peacock provides a good view of the internal facilities of the original pub, from the Morning Advertiser on the 19th May 1823:

“That old-established Free Public House and Liquor Shop, the PEACOCK, the corner of Haydon-street, Minories, in the City of London, comprising five good sleeping rooms, club room, bar, tap, kitchen, and parlour, and good cellar, held on lease for 18 1/4 years, at the low rent of £45 per annum.”

Newspaper reports that mention the Peacock include the full range of incidents that would be found at any city pub over the last couple of hundred years – thefts, the landlord being fined for allowing drunkenness, betting, sports (boxing seems to have been popular at the Peacock, etc.) however one advert shows how pubs were used as contact points, and tells the story of one individual travelling through London in 1820. From the Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser on the 29th May 1820:

“WANTED, by a PERSON who is 30 years of age, and who has been upwards of three years in the West Indies, a SITUATION to go to any part Abroad, as CLERK in a Store or Warehouse, or in any way he may be able to make himself useful. Address (post paid) for A.B. to be left at the Peacock, in the Minories”.

It would be fascinating to know “A.B’s” story, did he get another job, and where he went to next.

On the southern corner of Ibex House is a rather splendid sandwich bar, all glass and chrome:

The main entrance to the building looks almost as if you are entering a cinema, rather than an office building:

During the first couple of decades, occupants of Ibex House illustrate the wide variety of different businesses that were based in a single London office block, including:

- Shell Tankers Ltd – 1957

- Johnston Brothers (agricultural contractors) – 1952

- Associated Lead Manufacturers Ltd – 1950

- Vermoutiers Ltd (producers of “Vamour”, sweet or dry Vermouth) – 1948

- The Royal Alfred Aged Seamen’s Institution – 1948

- Ashwood Timber Industries – 1947

- The Air Ministry department which dealt with family allowances and RAF pay – 1940

- Cookson’s – the Lead Paint People – 1939

- Temple Publicity Services – 1938

The Associated Lead Manufacturers advertised “Uncle Toby’s Regiment of Lead” as their special lead alloy was used widely in the manufacture of toy soldiers. It would not be till 1966 that lead was banned as a material for the production of toys due to the damage that lead could cause to the health of a person.

The front of Ibex House is impressive, but we need to walk down the two side streets to see many of the impressive details of the building. Ibex House is designed in the shape of an H, with wide blocks facing to the Minories, and at the very rear of the building, with a slightly thinner block joining the two wider.

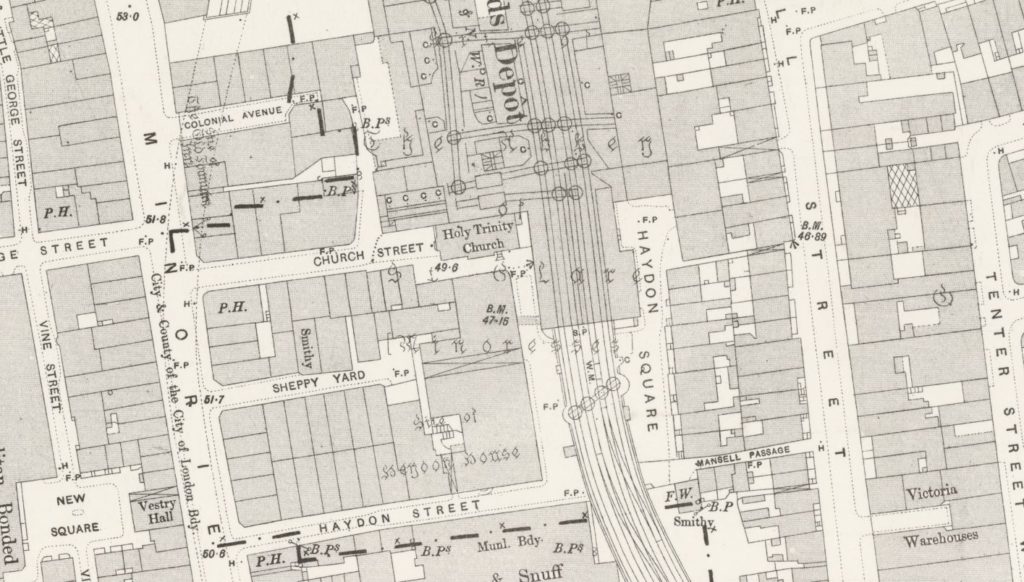

Walking along Haydon Street we can see the northern aspect of the building (Haydon Street was also the southern boundary of the Abbey of the Order of St Clare / the Minories).

The central glazed column contains small rooms on each floor level. There are few sharp corners on the building, mainly on the very upper floors, with curves being the predominant feature.

Looking back up towards the Minories:

The stepped and curved floors and railing on the upper floors give the impression of being on an ocean liner, rather than a city office block:

Curved walls feature across the building, including the corners of the ground floor which are tucked away at the end of the street:

Portsoken Street provides the southern boundary of the building:

Detail of the projecting canopy roof at the very top of the central, glazed column:

With a small room at each floor level:

The design detail includes curved windows in the glazed column that open on a central hinge:

Larger room at the top of the glazed column – a perfect location for an office with a view:

As well as the main entrance on the Minories, each side street also has an equally impressive central door into the building:

Ibex House is a very special building.

The view back up the Minories from near the southern end of the street:

The sisterhood of the “Sorores Minores” of the Order of St. Clare have left very little to tell us about life in their Abbey, and there are no physical remains of their buildings to be found, just the street names Minories and St Clare Street. Just one of the many religious establishments that were a major part of life in the city from the 12th century onwards.

So although we cannot see anything of the abbey, the Minories does give us the architectural splendor of Ibex House to admire as a brilliant example of 1930s design.