If you are in the vicinity of Fenchurch Street and head down Mark Lane, a short distance along you will see a church tower standing alone, surrounded by modern buildings that are significantly taller than this relic of a much earlier time. This is all that remains of the church of All Hallows Staining.

My father photographed the church tower in 1948:

Seventy years later in 2018 I took the following photo of the tower of All Hallows Staining:

Both photos were taken from Dunster Court, the street that runs from Mark Lane to Mincing Lane, running past the Clothworkers Hall.

The exterior of the tower is much the same in both photos, however since 1948 the windows and entrance arches have been in filled with glass and wooden doors, and there is a roof to the top of the tower.

The 1948 photo gives the impression that as with many City churches, this was all that remained following wartime bombing, however for All Hallows Staining, this was not the case as by the start of the last war, All Hallows Staining had already been reduced to just the tower for some years.

The immediate area of the church does show though, the level of general debris that could be found across the post war City.

In front of the tower in the 1948 photo is a large wooden cross. After the war a temporary church was set up adjacent to the tower to provide a temporary place of worship following the destruction of the nearby St. Olave in Hart Street.

This is the view of the tower from Mark Lane. This space was once occupied by the body of the church.

A wider view from Dunster Court showing how the surrounding buildings now tower over the remains of All Hallows Staining.

The building on the left of the above photo is the hall of the Clothworkers’ Company. The Hall was severely damaged during the war, and was in the gap on the extreme left of the 1948 photo. The Clothworkers’ lost a significant amount of historic items including the loss of their library.

The Clothworkers’ Company have taken on the maintenance of the tower and crypt of All Hallows Staining. The arms of the Clothworkers’ can be found on the pillars between the old churchyard and Dunster Court.

The tower of All Hallows Staining is very different to the majority of the City churches which typically have a steeple or spire and conform to the style introduced by Wren during the post Great Fire rebuild of the City churches.

This difference in style indicates the age of the church and that it is a survivor from before the Great Fire of 1666.

Writing in his book “London”, George Cunningham describes All Hallows Staining as “one of the earliest London churches to be built of stone – possibly the very first – and if so it must have dated from very early times. The church is first mentioned in 1335, and the tower dates from about a century later. Although the church escaped the Fire in 1666, it fell down in 1671; rebuilt 1673. but removed except for the tower in 1870.”

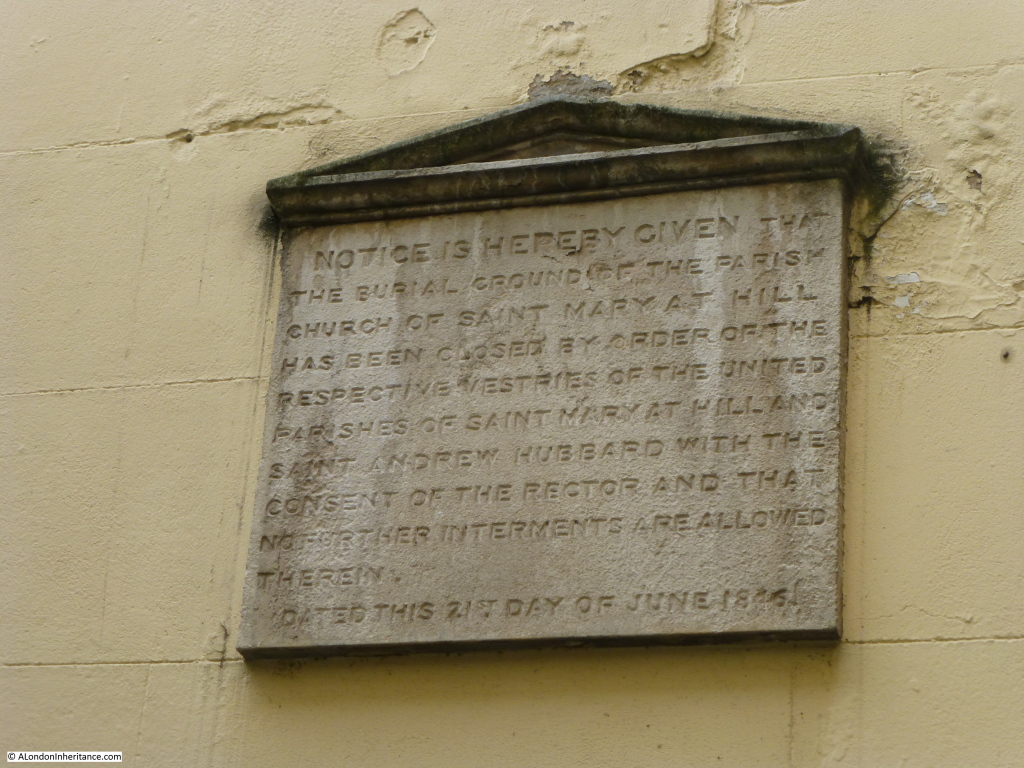

The information plaque in frount of the church attributes the collapse of the main body of the church to the weakening of the foundations due to the large number of burials in the churchyard.

In the Pevsner guide to the City of London, All Hallows Staining is described “Pulled down in 1870 except for the humble and much-restored medieval tower. The church is recorded by the late 12th century. The tower’s lowest stage may be of this date, though the earliest firmly datable feature is the early cinquefoiled two-light west window. The northwest stair turret, late 14th or 15th century seems formerly to have extended to a vanished top stage.”

Writing in “London Churches Before The Great Fire”, (1917) Wilberforce Jenkinson describes All Hallows Staining:

“Of All Hallows Staining, Stow writes:

‘commonly called Stane Church (as may be supposed) for a difference from other Churches, which of old were builded of timber’,

but the explanation is not very satisfactory. He says of a street called Stayning Lane that it was so called of Painter Stainers dwelling there, and that the small Church of St. Mary Stayning took its name from the Lane. Mr. Kingsford, Stow’s latest editor, thinks the name is explained by a reference to the ancient ‘parochia de Stanenetha’ (Stonehithe). Stow adds that most of the ‘fayre monuments of the dead were pulled downe and swept away and that the Churchwardens accounts shewed 12 shillings for brooms’. At the present time all that is left of this church, viz. the square stone tower and part of the churchyard, can be seen from Star Court, Mark Lane.

It would appear that the church was built before 1291. According to the London Register, which commenced in 1306, the first rector was Edward Camel, who died in 1329. The church was not burnt in the Great Fire, although the flames approached very nearly, but not long after the main part of the church fell suddenly. It was rebuilt (in part) at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Portions of the old church remained, for a drawing by West engraved by Toms in 1736, shows the old tower and a portion of the church having a Gothic style window of the decorated period.”

The drawing mentioned by Jenkinson by West and engraved by Toms is shown below:

The drawing shows a rustic view of the church with a rather empty churchyard. The enlarged, rounded corner of the church tower (which presumably enclosed spiral stairs leading up to the roof of the tower) is still to be seen and means that we can locate the position of the artist who was in the south west corner of the churchyard. The main body of the church is heading east from the tower towards Mark Lane.

The text at bottom right of the drawing also states the source of Stayning to be from Stone Church to distinguish the church from other wooden churches. The text also records that “John Costyn who died so long ago as 1244 left 100 quarter of Charcoal yearly to ye Poor of the Parish for ever.” Looking around at the buildings in the vicinity of All Hallows Stayning, I doubt there is anyone in need of Charcoal today.

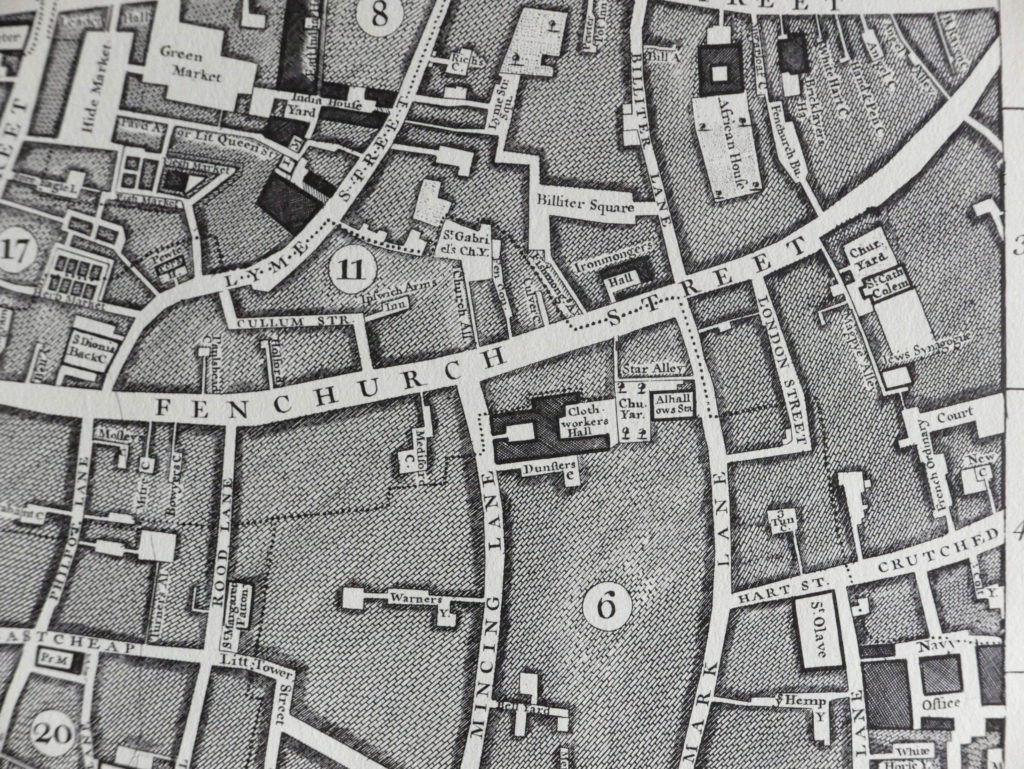

Ten years after the above drawing of the church was completed, John Rocque published his map of London and the following extract shows the area, with the church shown just below the centre of the map:

The map shows Fenchurch Street running west to east with Mincing Lane and Mark Lane running to the south. Just below Fenchurch Street and up against Mark Lane can be seen the church with the churchyard to the rear.

Star Alley is seen running alongside the churchyard before taking a sharp right turn at the end of the churchyard up to Fenchurch Street.

Between the churchyard and Mincing Lane is the Clothworkers Hall and Dunsters Court.

The area is still much the same. Star Alley continues to run alongside the old churchyard and takes a sharp turn up to Fenchurch Street. The Clothworkers’ Hall is still to be found along with Dunster Court to the south of the hall (the ‘s’ at the end of Dunsters appears to have been dropped).

The entrance gates to Dunster Court from Mincing Lane:

The following view is of the north west corner of the tower showing the 14th or 15th century stair turret as described in the Pevsner guide.

The photo was taken in Star Alley at the point where the alley makes a 90 degree bend towards Fenchurch Street.

From this point, a solitary grave can be seen in all that remains of the churchyard:

The grave is from the 1790s (I could not make out the last digit) and is of John Barker, his wife Margaret and their son Robert.

It is always worthwhile looking at surrounding buildings. On walking into Star Alley from Mark Lane, I found the two tiles shown in the following photo stuck to the wall bordering Star Alley. No idea of what they mean, for how long or why they are there, but the tiles appear to be about the construction industry that is so much a part of the City.

Star Alley runs alongside the old churchyard, and at the end of the churchyard it makes a 90 degree bend where it then runs through the surroundings buildings to Fenchurch Street. It is good to see that the exact alignment of Star Alley as shown in Rocque’s 1746 map has been retained.

It is remarkable that the tower of All Hallows Staining has survived for so long without a functioning church. The tower, churchyard, Star Alley, Dunster Court and the Clothworkers’ Hall form a small City landscape that is the same as mapped in 1746 and may date back to around 1456 when the Shearmen (the predecessors of the Clothworkers’ Company) purchased the land in Mincing Lane.