The University of London was founded in 1836 and went through a succession of locations within London, firstly in Somerset House, then Burlington House, from 1870 in Burlington Gardens, then in 1900 to the Imperial Institute, before starting the move to their new, custom built head offices, Senate House in Bloomsbury, one hundred years later in 1936.

In 1951 my father took a couple of photos showing the building which at the time was the tallest office building in London.

The same view is shown in the photo below, taken in 2018 from Keppel Street.

The Senate House building looks much the same and just as impressive. The building on the left of the photo is the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. In the 1951 photo there are some wonderful street lights either side of the entrance to the building on the left. They demonstrate how today there is far more street furniture, and there is far less design of what is installed along the streets above the minimum needed for functional and cost effective operation. In the same street today there is a parking pay station, a street lamp and a number of street signs – very different to the 1951 view with a clean street scene and a pair of well designed street lamps.

The following photo was taken from Montague Place, looking across to the tower and one of the lower office blocks that radiate out from the central tower.

The same view today is shown in the photo below. The small trees which can be seen in the above photo have grown significantly over the intervening years. Had I taken the same photo in a couple of months, leaves would have almost fully obscured the views of Senate House.

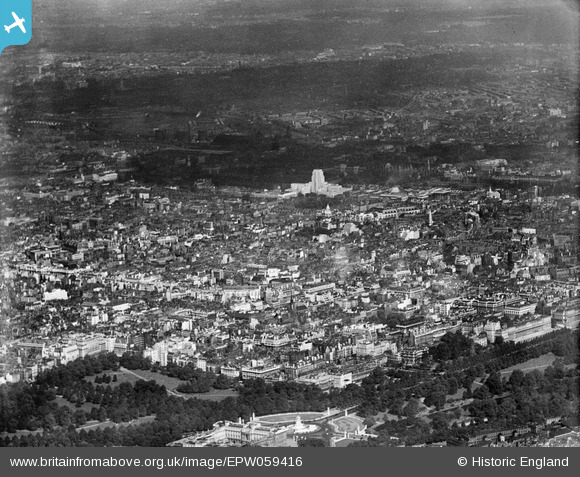

Senate House is a very impressive building. It is surprisingly well concealed as you walk around local streets, the view of the tower will suddenly appear then disappear between buildings. An aerial view is needed to really appreciate how the building stands out. The photo below from the Britain from Above website shows Senate House soon after completion, in the centre of the photo, with the clean Portland Stone facing of the building helping it to stand out from the surrounding streets.

Senate House today is a remarkable building, one that I suspect that if there were proposals to demolish would result in lots of complaint and demonstrations, however it replaced a dense network of Georgian buildings.

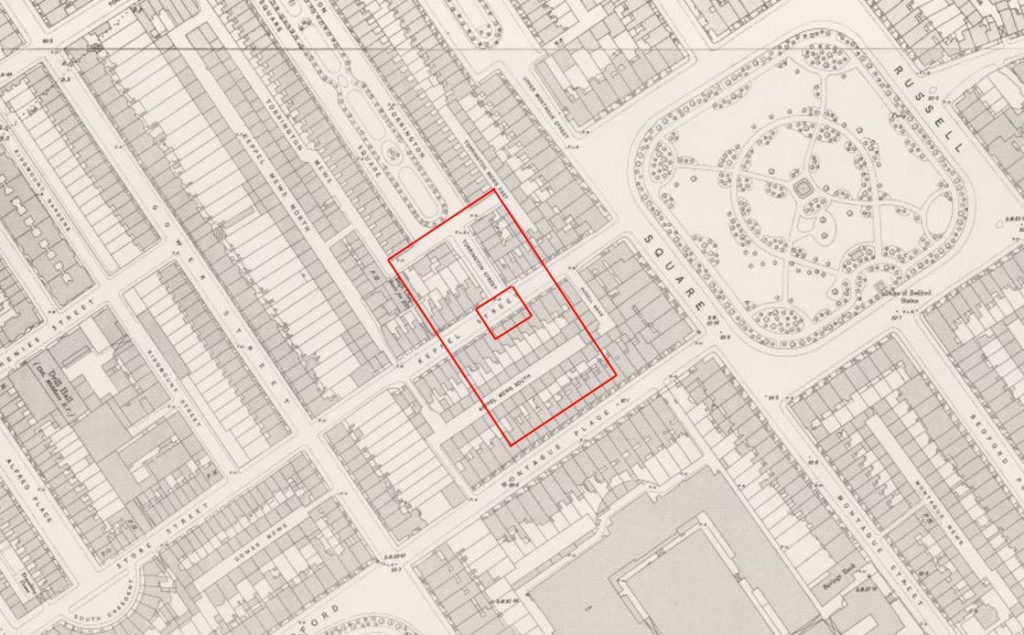

The following extract from the 1895 Ordnance Survey map shows the area around Senate House, with the outline of the overall complex shown by the larger red rectangle, with the smaller central rectangle showing the future location of the tower.

Although a significant part of Keppel Street was demolished to make way for the Senate House complex, a small section still survives leading up to Gower Street. Within this section of Keppel Street is an old boundary mark which illustrates the age of the streets.

Planning for a new location for the University of London started in the 1920s when Sir William Beveridge persuaded the Rockefeller Foundation to provide funding of £400,000 for a new university head office.

A 10.5 acre site in Bloomsbury was purchased.

In 1931 Charles Holden was selected as the architect for the new building. As well as Senate House, he was also the architect for a number of London Underground stations as well as the head offices of the London Underground at 55 Broadway – he has certainly left London with some iconic buildings.

His proposals were for a building that would last 500 years and offer the University a significant amount of space to consolidate their resources and offer space for expansion.

Holden did not go for a steel structure, rather his design was based on a self supporting masonry structure with internal brickwork and stone facing, which he believed would be more durable.

Holden’s initial design proposed a much larger building than we see today. It was cut back considerably to match the funding available. This initial design is shown in the following drawing which includes the large tower and surrounding buildings that would be built, however the structure continuing back towards a smaller tower stretched the available budget too far and remains one of the many “what ifs” of building design across London.

The following aerial photograph shows the proposed site for the new university building outlined by the white line. The photo was taken before construction started. Senate House was built on the area to the right, in the area that had already been cleared. Holden’s original plans would have occupied the whole area bounded by the white line.

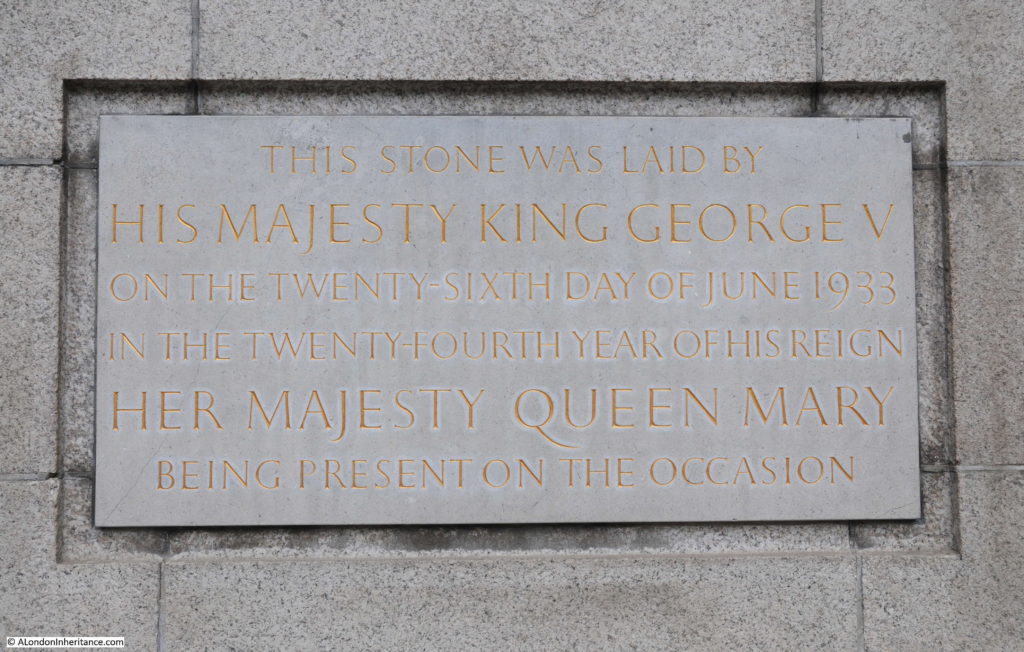

Construction started on the 29th December 1932 with over 1,300 concrete piles driven into the ground below basement level to provide support for the building that would rise above.

On the 26th June 1933, King George V laid the foundation stone for the new building. It was an impressive ceremony with over 3,000 people attending. The foundation stone is still to be found in its original setting.

In 1934 work started on the building above ground level. Up to first floor level engineering brick was used, faced by grey Cornish granite, the walls at ground level were 3ft, 4.5 inches thick. Above first floor level, Portland Stone was used to face the brickwork.

By 1936 the lower administrative block were ready for occupation by university staff.

The tower of 209 feet would be completed in September 1937 with the lower north wing being completed one year later. Further development of the complex continued until the outbreak of war in 1939.

John Curry of Personal Films Ltd was commissioned to film the construction of Senate House, however his work only ran up to the placing of the foundation stone. To mark the 50th anniversary of Senate House, the University of London took the individual parts of the film and released as a single copy. It is a fascinating view of the initial stages of construction as well as 1930s construction techniques when health and safety equipment extended to a flat cap and rolled up shirt sleeves.

The film can be found here – it really is worth a watch.

I have taken a couple of screen shots from the film. The first shows Charles Holden (on the right) with Dr. Edwin Deller, the Principal of the University of London. They are surveying the location of Senate House in the early days of site clearance.

Dr. Edwin Deller would later tragically die in November 1936 following an accident onsite during construction when a skip fell on a group of University staff.

Another screenshot shows a view across the construction site:

The north and south wings of Senate House along with the tower had been completed by the end of 1938, and staff from the University of London had moved into the building, however their occupation of the new landmark building would not last for long.

The Ministry of Information

On the outbreak of war in 1939, Senate House was taken over by the Ministry of Information – a function for which the design of the building, particularly the tower seemed very well suited. After the war, George Orwell would use Senate House as the inspiration for the Ministry of Truth in his book 1984.

The Ministry of Information was responsible for an extensive range of Government communication and information, including, censorship, news, publicity and propaganda, films, radio broadcasts, pamphlets, exhibitions at home and across allied countries.

A large room was set up in the Senate House for news briefings. Other activities carried out included reviewing and censoring news and photographs, the design and build of travelling exhibitions, design of posters, planning and implementation of publicity campaigns, teams for photography and filming to support the aims of the Ministry of Information.

The following photo shows a Ministry of Information mobile film unit leaving Senate House:

One of the ongoing publicity campaigns of the Ministry of Information was to show what could be achieved despite the very significant rationing of so many different products.

This included clothing and fashion and the Ministry of Information produced photos and the supporting messages to show what could be achieved with limited resources. Many of these photos were taken in the area around Senate House, including the following photo of a model on a rooftop in Bloomsbury with Senate House in the background. The message was that austerity fashion does not have to be drab and the model is wearing a design by Norman Hartnell with the material being available for seven clothing coupons.

From the start of operation, the Ministry of Information was very unpopular with the news media. The requirement for censorship, the limited provision of information, and how information was controlled and distributed were all a cause for concern.

The speed with which the Ministry of Information was set up, along with the majority of people working for the Ministry having no media background caused a rather chaotic start.

This was not helped by the rapid change of ministers in charge of the operation. The Ministry of Information went through three different ministers before stabilising under Brendan Bracken in July 1941.

Press reaction to the Ministry of Information can be understood by the following article printed in “The Sphere” on the 7th October 1939:

“The recently created Ministry of Information (it came into official being only on the outbreak of war) has aroused a storm of criticism from all sections of the nation in the brief month of its existence – both on account of its Censorship activity and on account of its meagre bulletins and ‘statements’. The position fairly stated would be (1) that what the public wants to know the Ministry will not tell it; and (2) that what the Ministry tells it the public do not want to know.

Even the Times, strong supporter of the Government, has been roused to make the strongest criticism of the Ministry.

The most serious criticism, however, came in the House of Commons last week when it was revealed that the total staff employed at the headquarters of this newest government department number 872, with a further 127 in regional offices.

But of this total of 999, only 43 were actually engaged in the profession of journalism at the time of their appointment. What the qualifications of the other 956 are for inclusion in a Ministry of Information we have not yet been told !”

The qualifications of those who worked in the Ministry of Information can be seen in the following photo which was captioned “Squadron Leader Elsdon (on left) censoring photographs at Senate House, London University”:

Another example of photography produced by the Ministry of Information. This one titled “How a British Woman dresses in wartime: Utility clothing in Britain in 1943”

The photo shows a utility suit purchased from Dickens and Jones for eighteen clothing coupons and 82 shillings and 2 pence. the photo was taken at the entrance to Senate House.

The Ministry of Information was also concerned with countering perceived threats to the nation’s willingness to fight. The ministry also set up local committees who would take action where there was a challenge, and the following article from the Worthing Herald on the 12th March 1940 titled “Organised False Pacifism To Be Fought” illustrates the actions of the ministry:

“The Ministry of Information is going to do everything it possibly can to fight the ‘organised false pacifism’ of the Peace Pledge Union.

This declaration was made at a Worthing meeting on Tuesday by Mr. H.S. Banner, Regional Information Officer, after he had been told by Councillor J.A. Mason that classes were being held ‘not far from here’ at which young men were given all the answers they might need when they come before Conscientious Objectors’ Tribunals.”

Travelling exhibitions were designed, tested and built at Senate House before being distributed across the country. The following photo shows part of a “Make Do And Mend” exhibition, with the poster on the left calling the population to “Make War On Moths”. The poster on the right titled “Forget About Clothes Convention” is advising people that they do not need to stick to conventions such as always wearing a hat, and that a hat was only required in specific weather conditions. This would help reduce the need for clothing materials. Campaigns such as this go some way to explaining how in pre-war photos people would nearly always be wearing hats, whilst post war, this convention had dropped significantly

The following photo shows a typical Ministry of Information travelling exhibition, parked outside Senate House.

The aim of the exhibition is to encourage the collection and recycling of materials essential for the war effort, or, as the sign on the side of the car proclaims “Private Scrap is in town…come and meet him”.

On the side of the van facing the rear of the car is a book collection point, “for the forces, blitzed libraries, and salvage”.

The Ministry of Information also had a fleet of travelling cinemas as this newspaper report explains:

“The Ministry of Information’s fleet of travelling cinemas is to give over 3,600 shows during 1942 in the Eastern region, according to a statement just issued reviewing the work of the past year and plans for the future. By the end of this year approximately 2,500 shows will have been given to an estimated audience of half a million people.

The story of the Ministry of Information’s ‘Celluloid Circus’, as it is sometimes affectionately called is a fascinating one. Since its birth a year ago the units have traveled thousands of miles, setting up their equipment each night to show their films in village halls in Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire, Huntingdonshire and Cambridgeshire.

it is a business of ‘one night stands’ – and then on to the next village next day. Sometimes it will be a ‘midnight matinée’ between shifts at a war factory; sometimes a ‘fit-up’ in a barn for a group of the new agricultural workers.”

It is remarkable how many operations and activities were undertaken by the Ministry of Information. All coordinated from the head offices of the ministry in the Senate House.

Towards the end of the war, various activities of the Ministry of Information started to wind down and academic staff and students began to return to Senate House. The Ministry of Information was finally disbanded in March 1946.

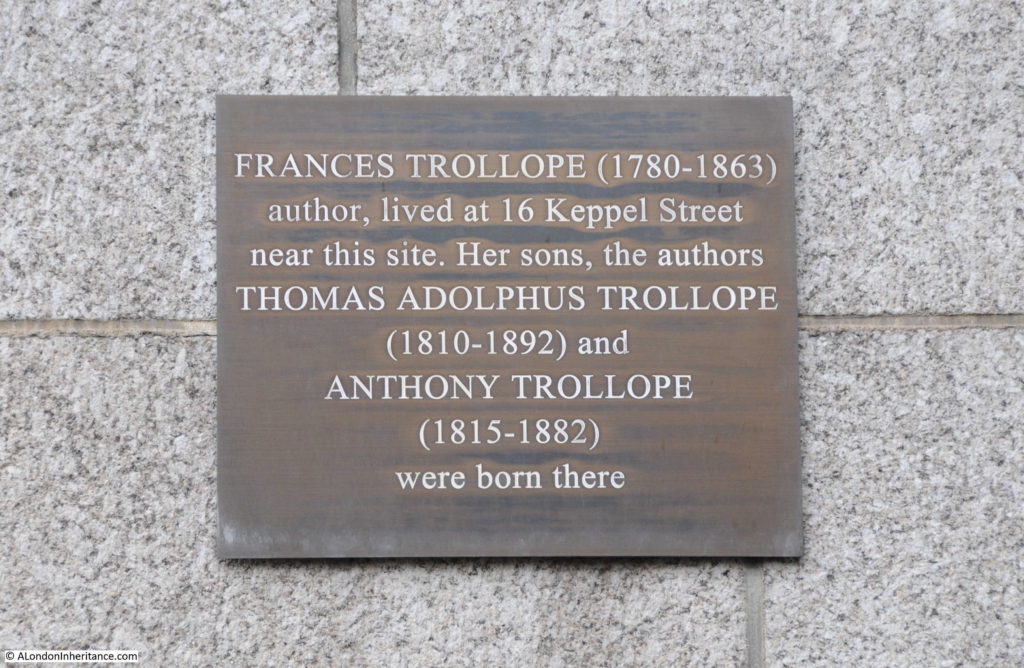

There are still some reminders of the streets that Senate House obliterated. For example in the courtyard of Senate House there is the plaque shown in the photo below to the Trollope family who lived in Keppel Street.

The building is a remarkable example of 1930s architecture. It is intriguing to wonder whether it will last for 500 years as proposed by Charles Holden. The building could also have been very much larger if full funding had been available and this part of Bloomsbury would have been very different. London is full of such speculation.