Bedford Square, Bloomsbury must be one of the best preserved, late 18th century squares in London, and in this part of London there is plenty of competition.

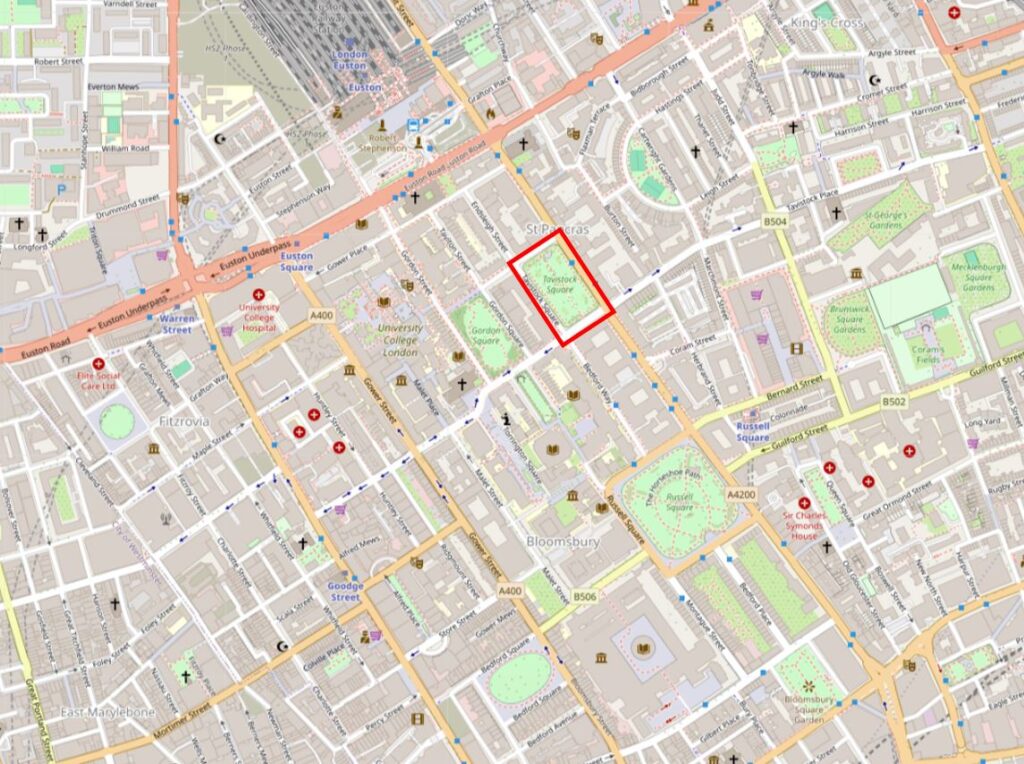

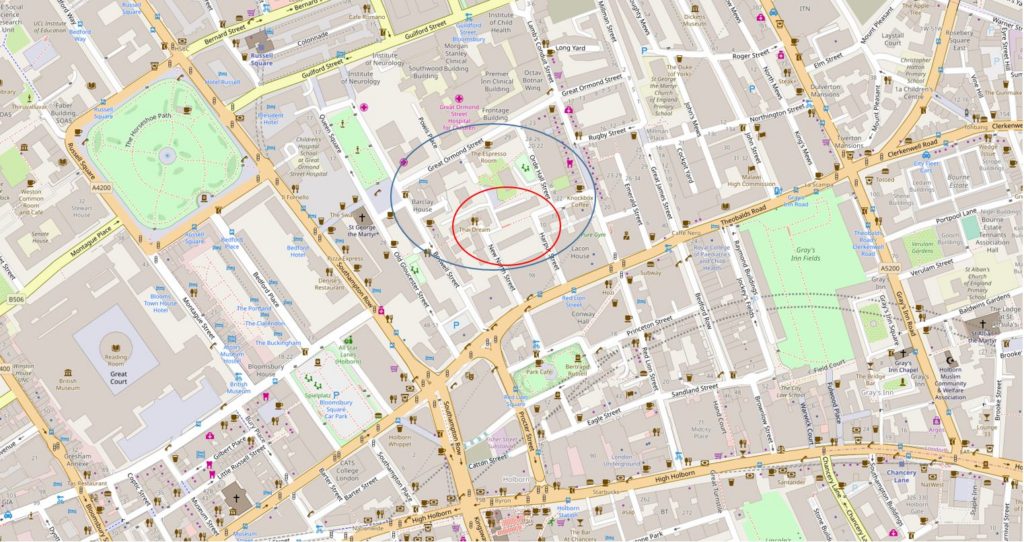

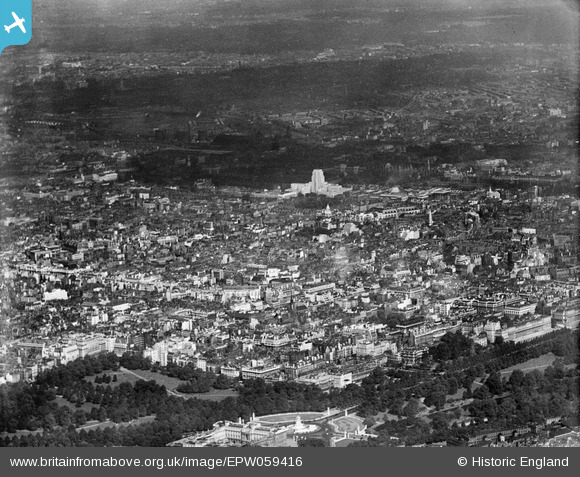

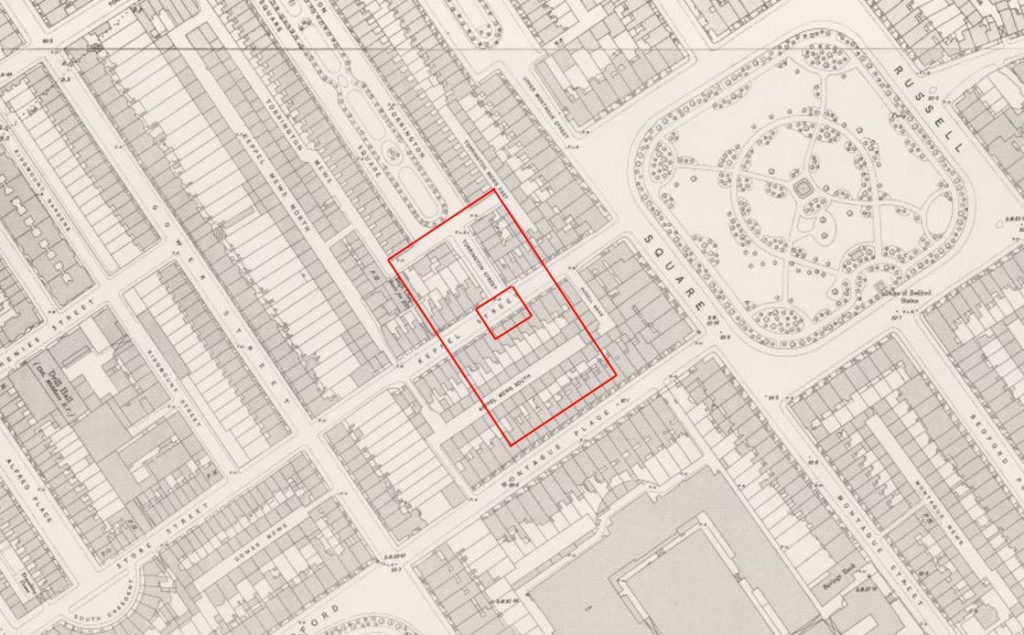

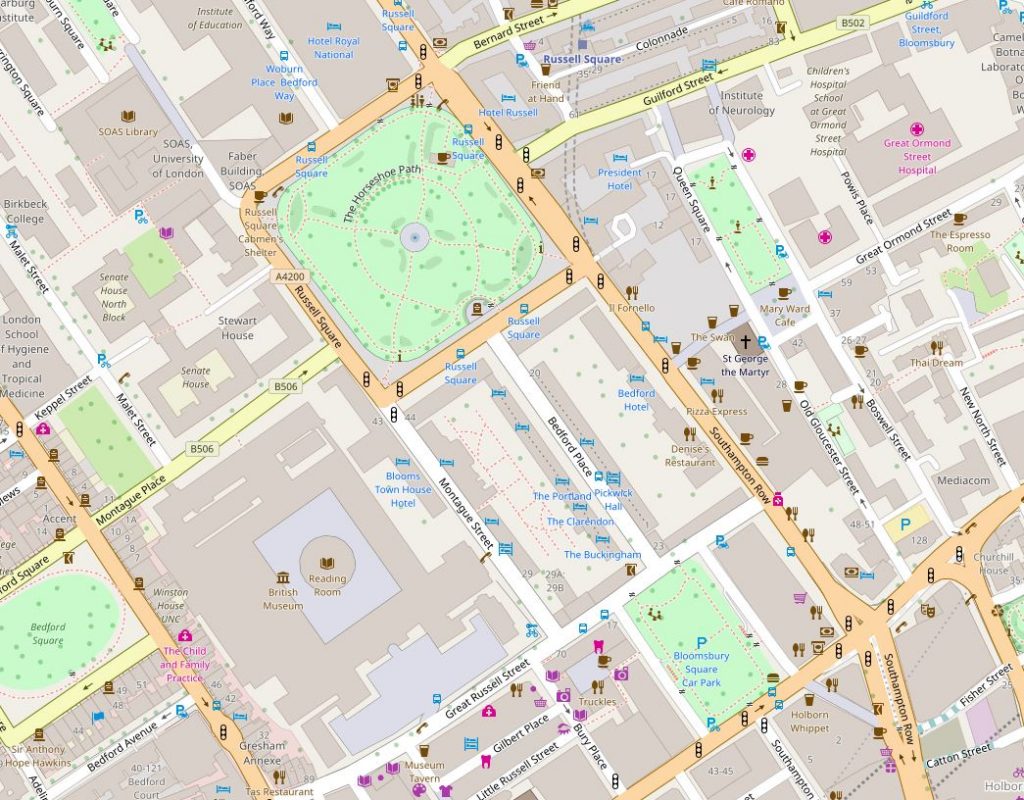

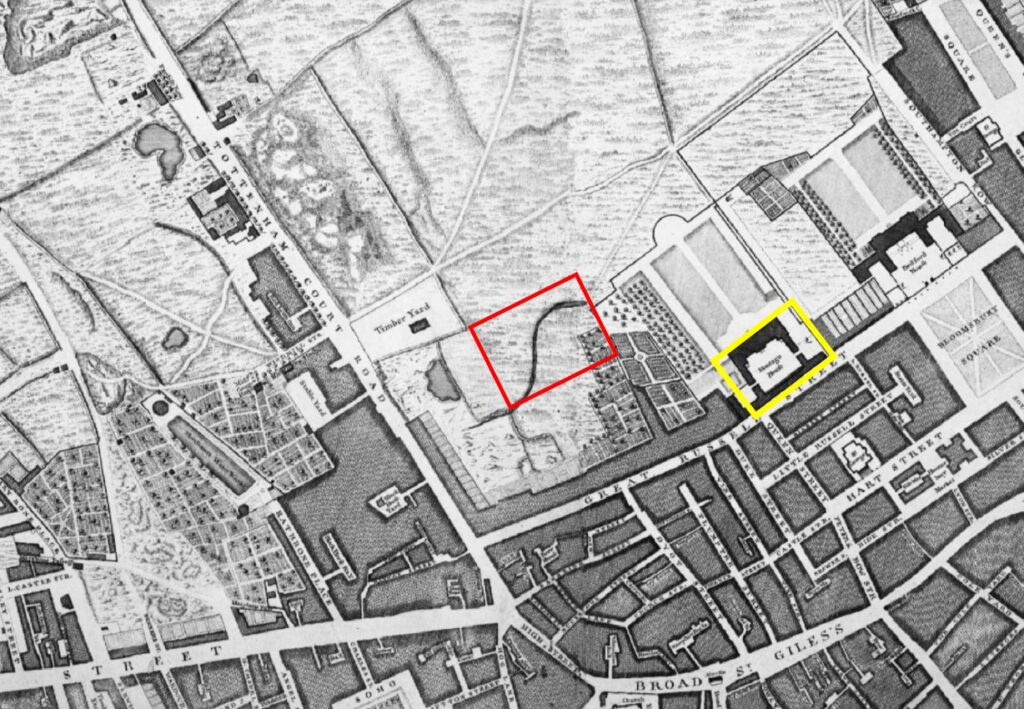

Bedford Square is just north of New Oxford Street, and has the British Museum to the east, and Tottenham Court Road a short distance to the west. The following map shows the location of the square in red:

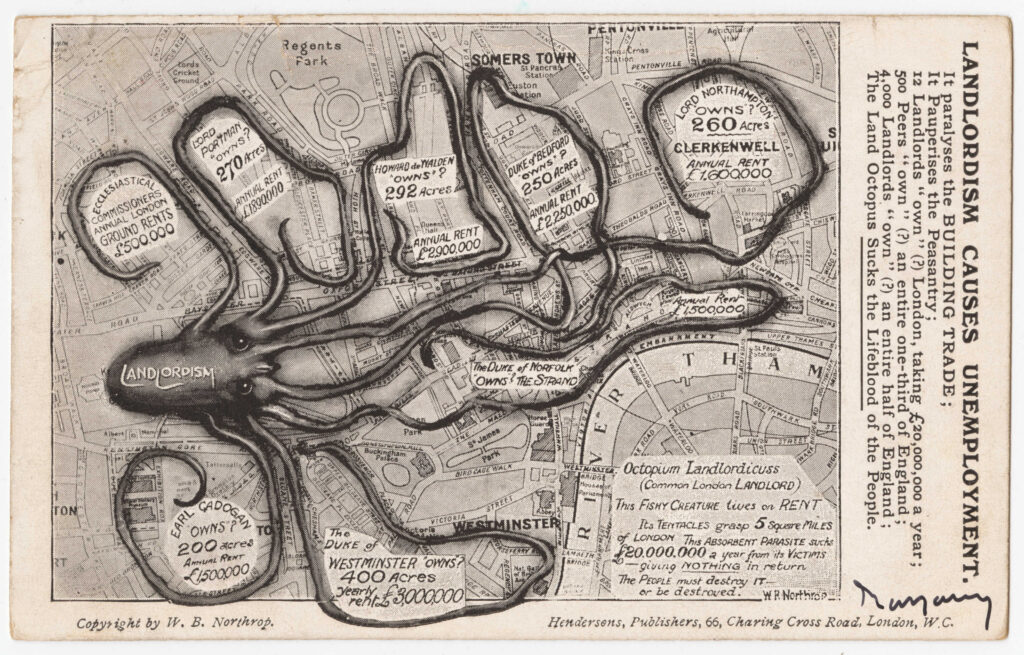

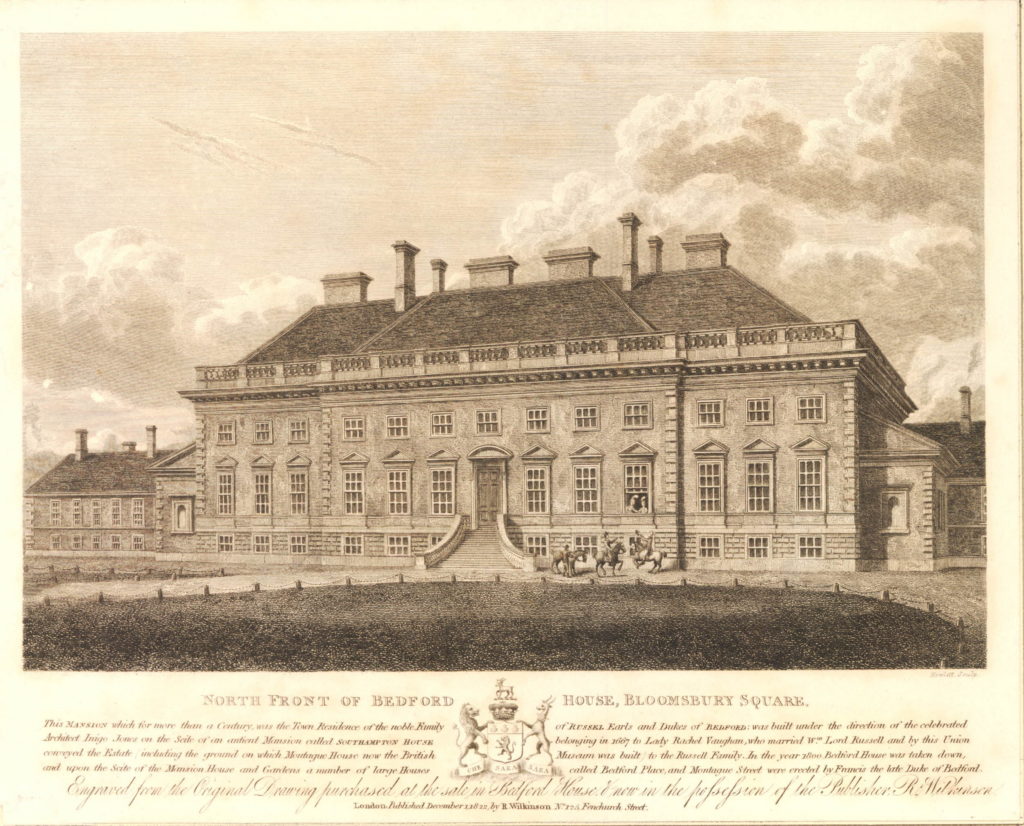

Bedford Square was planned and built between 1775 and 1780 as part of the development of the land owned by the Duke of Bedford (hence the name) within his Bloomsbury Estate.

This was a time when London was expanding northwards and the fields, streams, ponds and footpaths that comprised the Bloomsbury Estate would soon be part of the built city, however it would be a unique area due to the number of large squares which provided open, green space for the occupants of the new houses to enjoy.

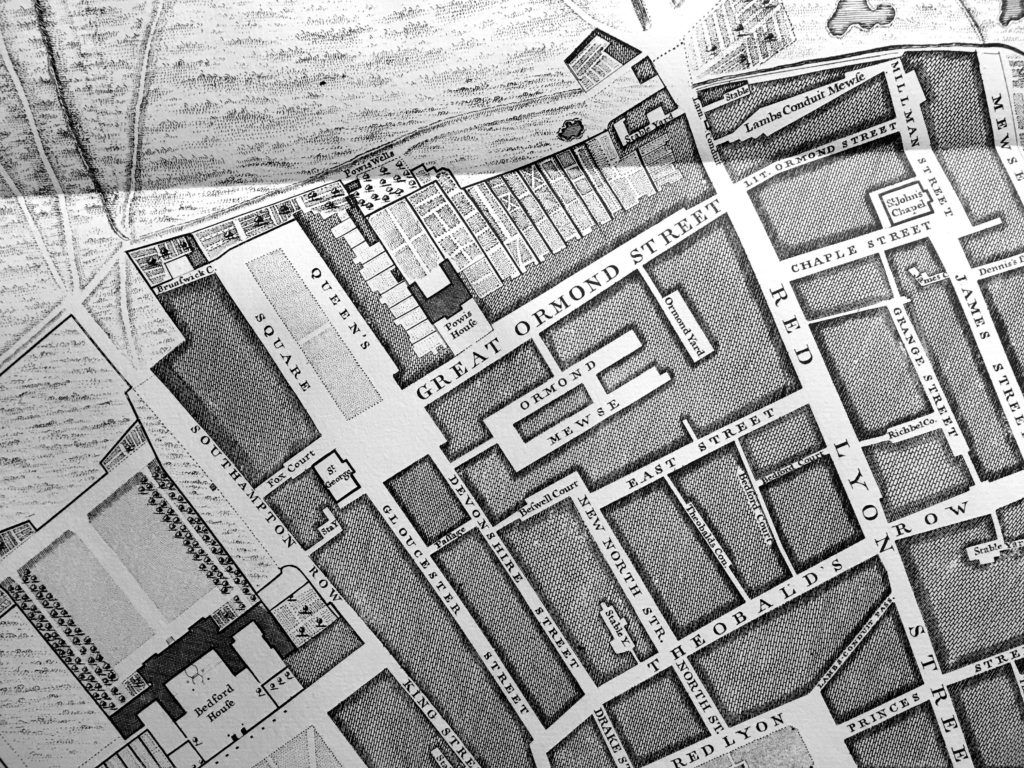

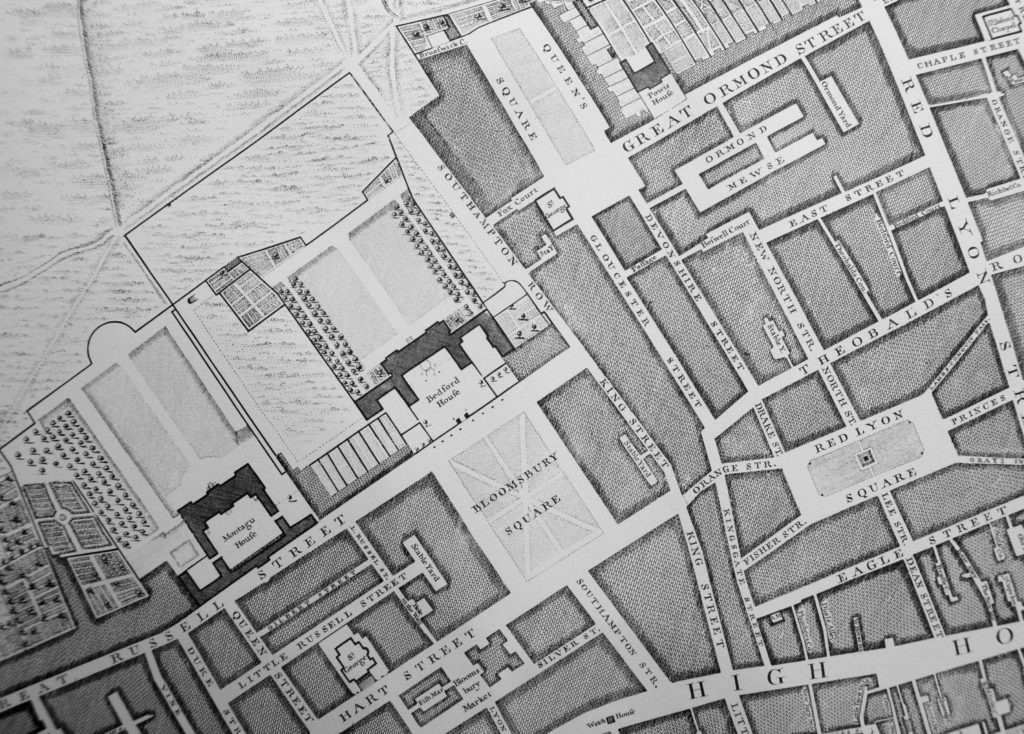

The following extract shows the area as it was not long before the development of Bedford Square. This is from Rocque’s map of 1746 and I have marked the future location of Bedford Square with the red rectangle, and much of the approximately 112 acres of the Bloomsbury Estate then open space:

The yellow rectangle is around Montague House, the future site of the British Museum.

Plots of land around Bedford Square were leased by the architect Thomas Leverton and builders, Robert Crews and William Scott.

it is believed that Thomas Leverton was responsible for the overall plan of the buildings lining the four sides of the square, although there is no firm evidence to support this.

Thomas Leverton was the son of the builder Lancelot Leverton who was based in Woodford, Essex.

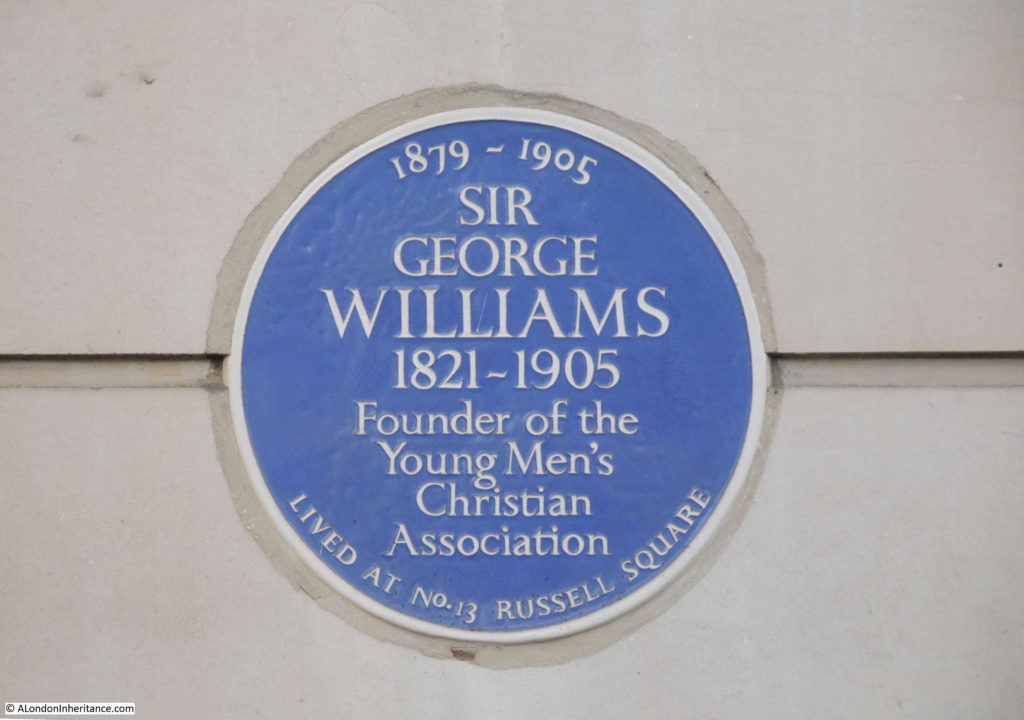

He seems to have designed a number of country houses, and where there is firm evidence of his connection with Bedford Square is with number 13 where he worked on the interior of the building and lived in the house from 1796 until his death in 1824.

Each of the sides of the square has the same basic design, which was intended to emulate the appearance of a large country house, with the central building decorated with stucco, along with pilasters and pediments.

The “wings” of this central house are the row of brick terrace houses on either side of the central house and that run to the corners of the square:

The above photo is of the northern side of the square and the photo below is of the eastern side. The overall design is the same however there are subtle differences, for example the central house on the north side has six bays, whilst that on the eastern side has five:

This seems to be down to the fact that the square is not really a square, rather a rectangle with the north and south sides being 520 feet long whilst the east and west are 320 feet.

To show how little Bedford Square has changed, the following print from 1851 is of the same view as the above photo:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The only things that have changed is the replacement of coach and horses by cars, wider paving and the amount of street furniture we see today.

The remarkable preservation of the houses in Bedford Square appears to be due to the way that the Bedford Estate has managed the square since its original construction.

Steen Eiler Rasmussen writing in “London: The Unique City” (1948 edition) gives a fascinating insight into how this worked.

The original land was leased as a number of lots where a house would be built, and for the first 99 year lease, the annual ground rent was £3 for each lot.

After 99 years, the Bedford Estate than became the owner of not only the ground, but also the house that had been built on the land, and it was then leased for an additional period for a new annual sum that reflected both the land and the house, so by the end of the 99 years of the first leasing period, houses were then leased at different values to reflect the type, design and condition of the house on the land.

After the first 99 years, as well as different financial values, the leases were also for different periods, between twenty and fifty years. This seems to have been based on the work that the new leaseholder was planning to put into the building, so a leaseholder making a considerable investment on repairs, rebuilding and improvements would have a longer lease period.

One of the benefits to the Bedford Estate of then having leases expire at different times was that it avoided the risk of the leases for all the houses surrounding the square being renewed, for example, during a period of financial depression and low demand, when lease values would have been reduced.

It also means that any plans for radical change across the square are difficult, as the leases all expire at different times, and so the leases that make up a large block of land would not all become available at the same time.

I have no idea whether the Bedford Estate still takes this approach, however it does help explain why the houses in Bedford Square have externally hardly changed since their original build.

Although the external appearance has hardly changed, the interior of the houses on Bedford Square may be very different, reflecting the changes that have taken place over the last few centuries. Different uses, different types of owner, all would have left their mark on the interior.

There are also subtle different to the external façade of the houses, for example, this end of terrace house has a metal veranda structure above the balcony that runs the full width of the house:

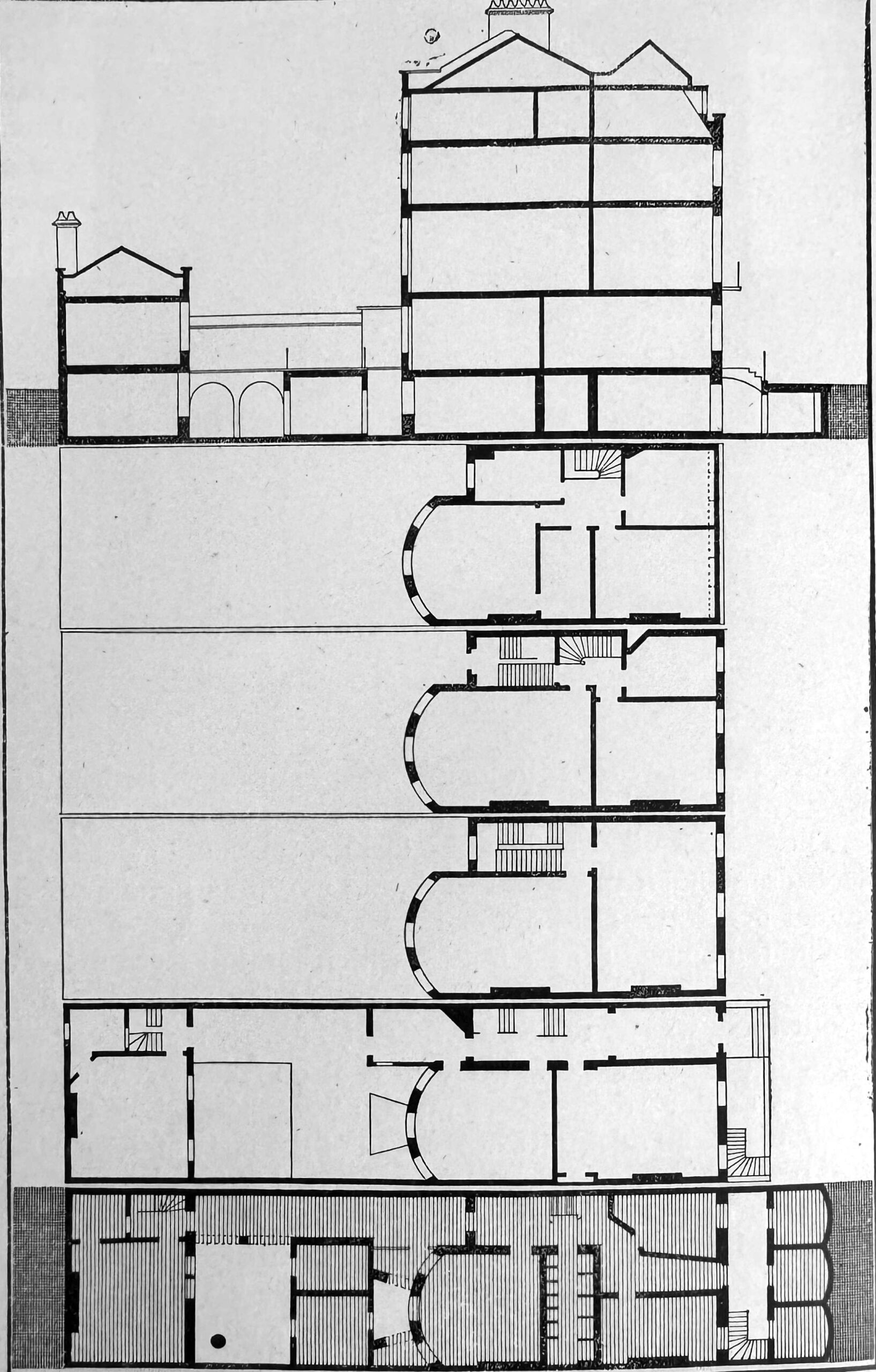

From the street, these houses look relatively narrow, however clever design results in a sizeable interior.

The following plan from the book London: The Unique City shows the layout of a typical house in Bedford Square:

Despite the narrow front facing onto the square, each house does extend a fair way back, with both the basement and the ground floors extending some distance, and storage areas which would have held consumables such as coal, extending underneath the pavement from the basement.

On the north east corner of Bedford Square, the house in the photo below has street signs indicating that it is at the corner of Gower Street and Montague Place:

However below the signs for these two streets are these much older signs indicating a Bedford Square address:

Much of the decoration around the doors of the houses is of Coade Stone, which was made in the factory owned by Eleanor Coade on the south bank of the river, just to the west of the Royal Festival Hall, and in the following photo Coade stone alternates with brick around the main entrances to the house:

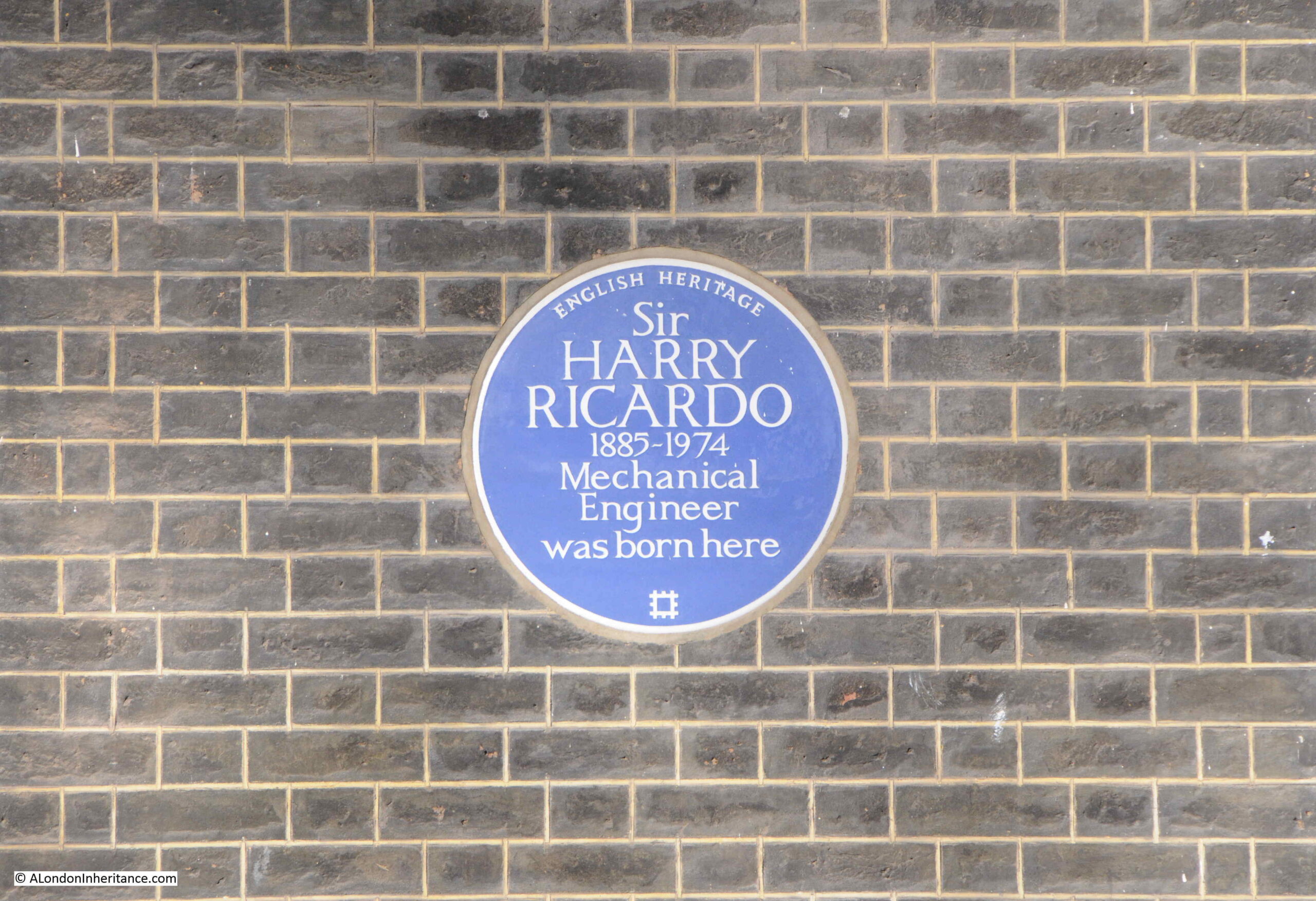

As could probably be expected for a location such as Bedford Square, there are a large number of blue plaques on the houses. On the house in the above photo is an English Heritage plaque to Sir Harry Ricardo:

As stated on the plaque, Sir Harry Ricardo was a Mechanical Engineer, and much of his work was centred around the development of the internal combustion engine for both vehicles and aircraft, and his work contributed to the outcome of the First World War as he developed the engines that were used by the tanks on the battlefield.

And if you fill up a car with petrol, and check the octane rating of the petrol, that is also down to Sir Harry Ricardo as his work on the chemical composition of fuels resulted in the octane classification system

The company he founded is still going strong, and is still named Ricardo, and is based at Shoreham-by-Sea in West Sussex.

The large central houses on the north and south sides of the square have six window bays, and two large entrances:

Whilst those in the centre of the other two sides, have five window bays, and a single entrance from the street:

To the right of the entrance to the building in the above photo, a London County Coucil blue plaque record that Lord Eldon (1751 – 1838), Lord Chancellor, lived in the house.

He does not appear to have been very popular in the role of Lord Chancellor as the following is typical of the obituaries that were published after his death;

“For five-and-twenty years Lord Eldon held possession of the woolsack. Here was a position and a power of doing good in the hands of any man honestly disposed towards his country. For a quarter of a century he had absolute authority over the very stronghold of legal corruption – over the crying grievance of the nation – over the engine which broke the happiness, destroyed the fortunes, and wore away even the lives, of no small portion of his fellow men.

What did Lord Eldon do? Did he make one effort to palliate the evil? Did he, in a single instance, exert his power to rescue its victims? Did he, by one gesture, encourage those who were labouring day and night to work out the reformation he could at once have accomplished?

No. Lord Eldon was their bitterest, their most determined foe. He exerted his mighty power, in his court, in the cabinet, and in the closet, to stifle all enquiry, to destroy all opposition, to render hopeless every effort for amendment. He threw his protection over every harpy which fattened upon the corruption of his court, and verily they flourished.”

He also does not appear to have been that popular with his daughter, as she eloped with G S Repton, who was the son of Humphry Repton, the designer of the gardens in nearby Bloomsbury and Russell Squares.

View along the western side of Bedford Square:

The above photo shows that there are subtle differences to the apparent identical design of the houses in the terrace. Look at the decoration around the entrances, and the central two have solid white stone decoration, whilst the outer two have a mix of white Coade stone and the same brick as the rest of the house.

The central gardens are private, and are for the residents of the square.

As well as the majority of the surrounding houses being listed, these gardens are also Grade II* listed.

They have not changed that much since originally being set out. The shrubbery around the perimeter of the gardens appear to be a long standing feature. In the 19th century, paths across the grass were removed.

There was limited damage to the square during the last war, with a single house in the southern side of the square damaged, along with the houses in the south east corner.

The shrubbery limits the views across the gardens, but glimpses are available as shown in the following photo:

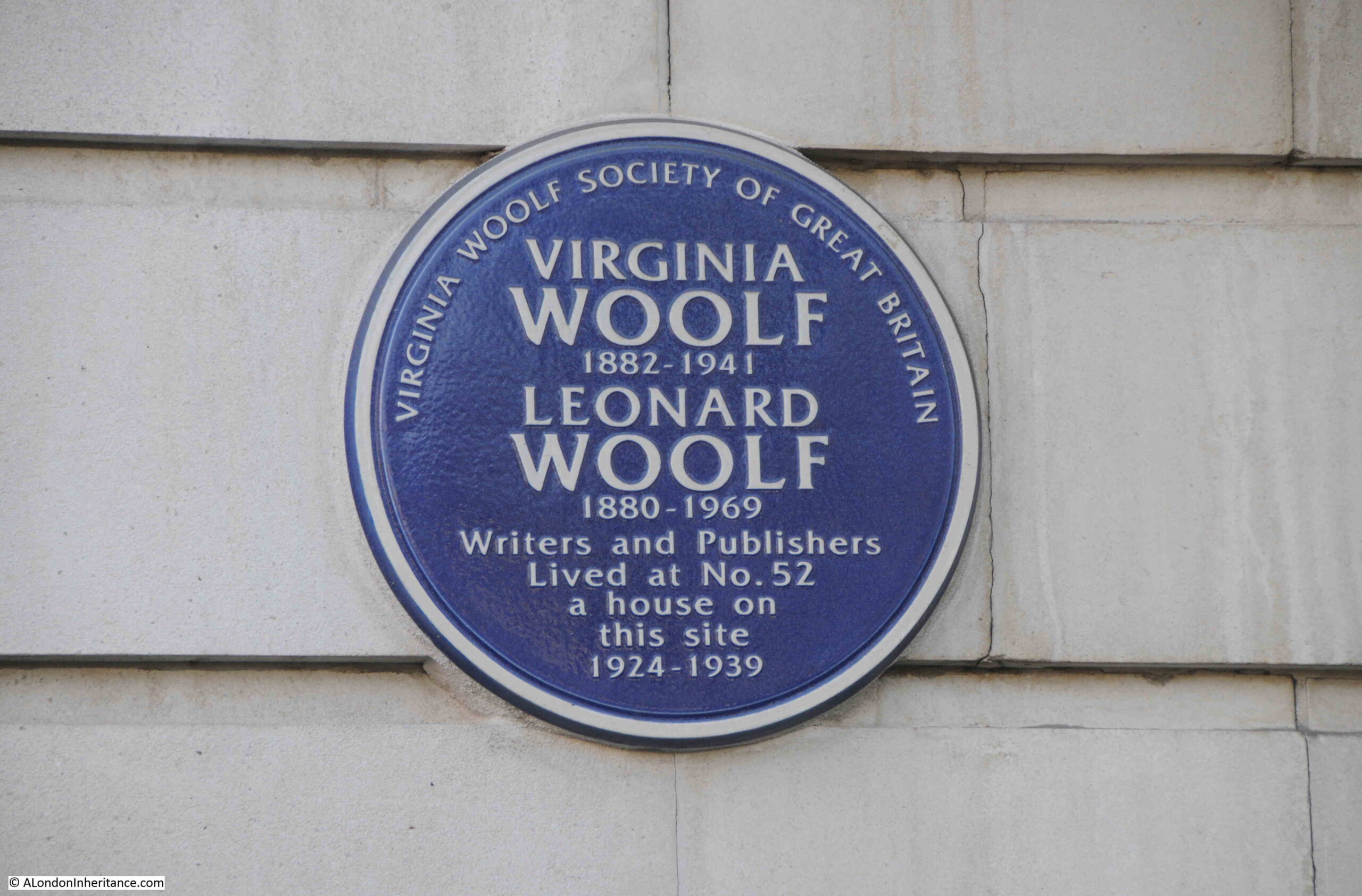

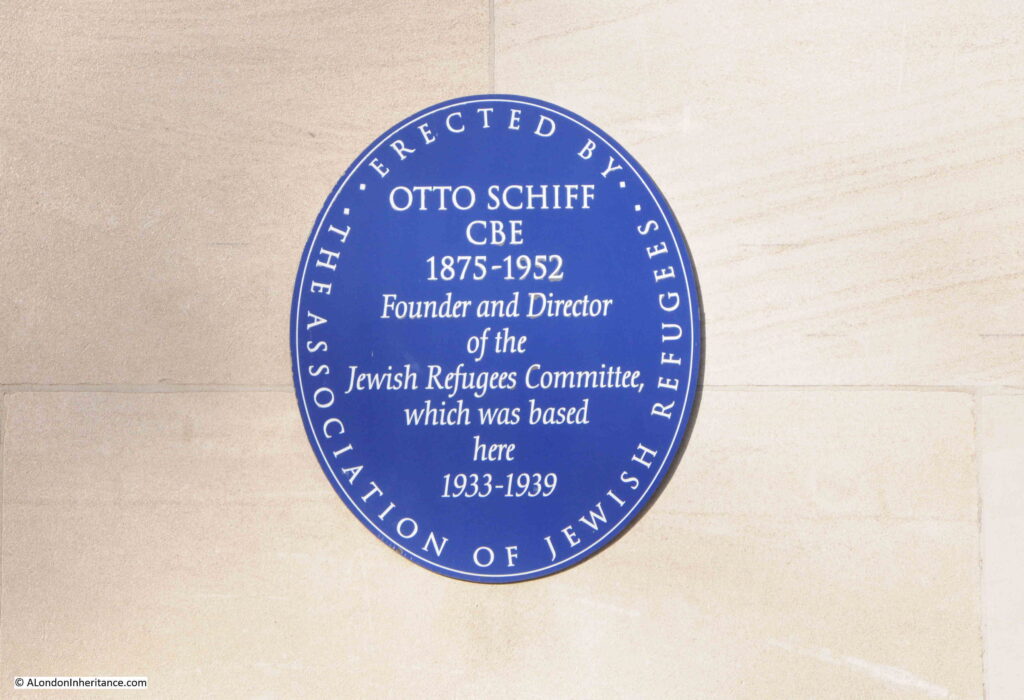

Another Bedford Square blue plaque on the house in the photo below:

This plaque is a perfect example of the range and diversity of people who have passed through London over the centuries.

The plaque records that Ram Mohun Roy, Indian reformer and Scholar lived in the house.

Ram Mohun Roy was born in Radhanagar, Bengal, India, in 1772. Although a Hindu, Roy studied all the religions he could find in India. He wrote and campaigned against religious superstition, and the caste system.

He was the founder of two of India’s earliest newspapers, but after the British imposed censorship of the Calcutta press in the 1820s, he started to campaign for freedom of speech, and became more involved in social reform.

He had come into contact with the East India Company, working as a translator as well as an assistant to East India Company staff.

in 1830, Roy came to England. An ex-emperor of Delhi had made Roy his ambassador so that he could plead the emperor’s cause with the authorities of the East India Company.

He was well received in London society (no doubt a Bedford Square address helped), and addressed the Unitarians (a dissenting Christian approach, where members follow their own beliefs rather than the doctrine of the Church of England). The Unitarians are still based in Essex Street off the Strand, where their first meeting was held in 1774, so it was probably here that Roy made his address.

He did not return to India, but died in Bristol during a visit at the invitation of Unitarian friends, and is now buried at Arnos Vale cemetery in Bristol.

On an adjacent house is a green plaque:

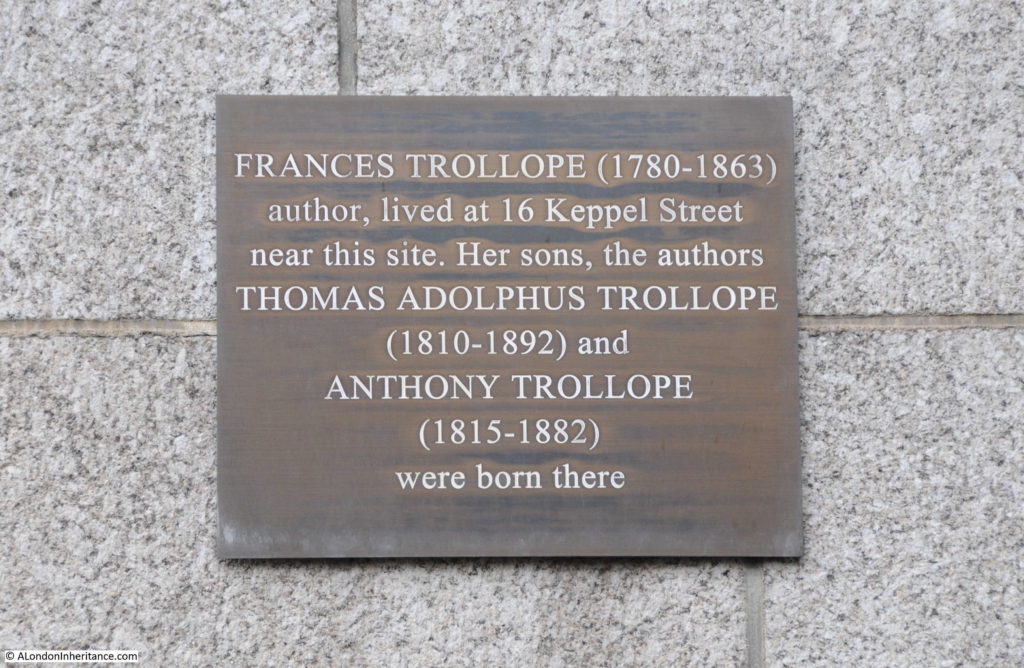

Recording that the Bedford College for Women, the University of London was founded in the house in 1849 by Elizabeth Jesser Reid.

There is a connection between Ram Mohun Roy and Elizabeth Jesser Reid, as she was the daughter of a wealthy Unitarian ironmonger and was born in 1789. She married Dr. John Reid, a nonconformist, and in 1849 she founded the Ladies College or College for Women, using her Unitarian and Bloomsbury connections to gather support, and to get teaching staff and professors to teach at the college.

The College was the first higher education establishment for women in the country.

It would stay in Bedford Square to 1874, when the lease came up for renewal. The Bedford Estate did not want to renew the lease with the college, so the college moved to larger premises near Baker Street.

Yet another blue plaque:

This one to an architect, William Butterfield.

Born in London in 1814, Butterfield trained as an architect and established his own architectural practice in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, before moving to the Adelphi.

He was involved with the study of Gothic Architecture, and the Victorian revival of religious architecture. This resulted in a considerable amount of work on churches and their associated building both in London and across the country.

William Butterfield died in his house in Bedford Square on the 23rd of February, 1900.

That is just a sample of the plaques to be found in Bedford Square.

Today, Bedford Square is home to a number of cultural institutions, including Sotheby’s Institute of Art, Yale University Press, and the New College for Humanities.

Bedford Square is one of those rare places in London, where, if you took away all the cars, a resident from the late 18th century, just after the square was completed, could return today and externally, the square would be perfectly recognisable.

It is also interesting to consider that whilst there is so much change across London, and there have been multiple different buildings on sites across much of London, when we stand in Bedford Square, we are looking at the only houses that have been built here, since the land was fields.

It is a lovely example of architecture and street planning.