All my walking tours have sold out, with the exception of a few tickets on the Bankside to Pickle Herring Street tour. Details and booking here.

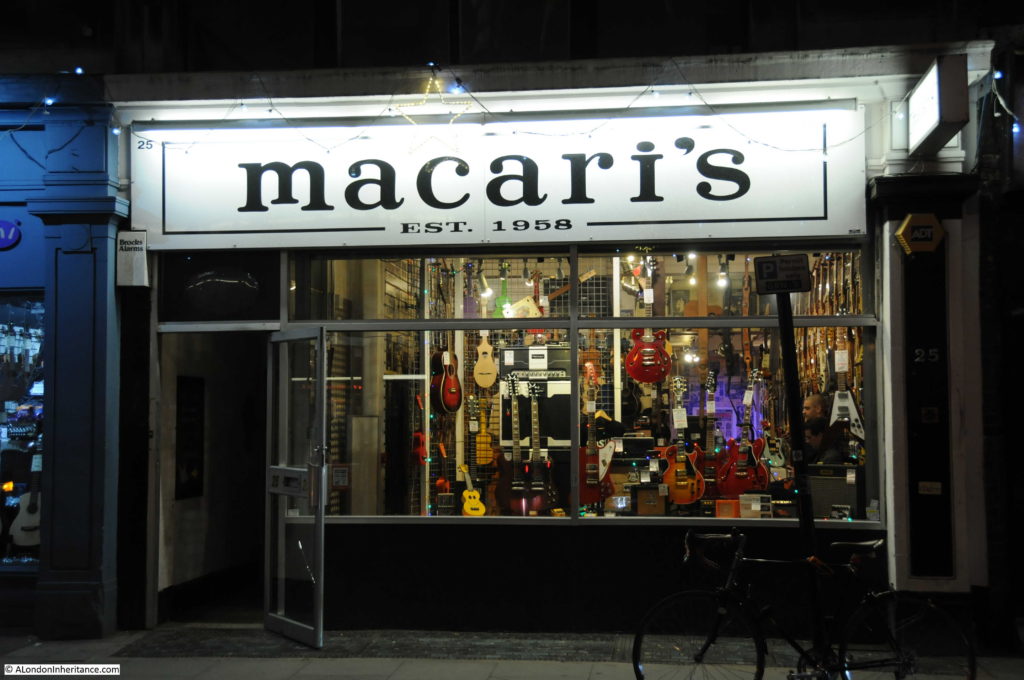

In 1980 I was wandering around London trying out a new zoom lens for my Canon AE-1 camera, taking some not very good photos. One of these was of the Champion Pub at the junction of Eastcastle Street and Wells Street, with the Post Office Tower in the background:

The photo was taken from the southern end of Wells Street towards Oxford Street, and a sign for Eastcastle Street can be seen on the right of the Champion pub. I think I was trying to contrast the old pub and the new telecoms tower.

A wider view of the same scene today, with the BT Tower as it is now known, starting to disappear behind the new floors being added to the building behind the Champion:

A closer view of the pub in 2022, 42 years after my original photo:

Given how many pubs have closed over the last few decades, it is really good that the Champion has survived, although it is a shame that the curved corner of the building has been painted, and it has lost the name which ran the full length of the corner of the pub.

The large ornamental cast iron lamp still decorates the corner of the building.

The curved corner to the upper floors was a key feature of many 19th century London pubs. They were meant to advertise the pub, the name could be seen from a distance on crowded streets, and the name would often give an identity to the junction of streets.

For an example of a pub which had a very colourful corner in the 1980s, and today displays the current name of the pub on the curved corner, see my post on the Perseverance or Sun Pub, Lamb’s Conduit Street.

The Champion is Grade II listed, and the Historic England listing details provide some background:

“Corner public house. c.1860-70. Gault brick with stucco dressings, slate roof. Lively classical detailing. 4 storeys. 3 windows wide to each front and inset stuccoed quadrant corner. Ground floor has bar front with corner and side entrances and fronted bar windows framed by crude pilasters carrying entablature- fascia with richly decorated modillion cornice. Upper floors have segmental arched sash windows, those on 1st floor with keystones and marks. Heavy moulded crowning cornice and blocking stuccoed. Large ornamental cast iron lamp bracket to corner. Interior bar fittings original in part with screens etc, some renewal.“

The “some renewal” statement refers to a few changes to the pub since it was built.

The first post-war renewal came in the 1950s. As with so many Victorian pubs across London, the Champion was in need of some refurbishment. Over 80 years of serving Wells Street, and open during the years of the second world war, resulted in the owners, the brewers Barclay Perkins, engaging architect and designer John and Sylvia Reid.

The Reid’s were better known as interior, furniture and lighting designers rather than architecture, and their changes to the Champion were mainly of design.

The large Champion name down the curved corner of the pub was a result of their work. The lettering was in 30 inch Roman, and the letters were shaded to give the impression that they had been engraved rather than painted. The new name replaced a number of old wooden signs that were mounted on the corner. The corner of the pub was floodlit at night, which must have looked rather magnificent, and ensured the pub stood out if you looked down Wells Street when walking along Oxford Street.

The interior had been rather plain and was painted in what were described as drab colours.

The Reid’s divided what had been two bars to form three, added button leather seating around the edge of the bars, restored the bar and some of the original iron tables, and they added new glass windows consisting of clear glass for the upper half and frosted, acid cut glass for the lower half.

Features inside the pub included the use of mahogany panels, etched and decorated glass windows between bars, and textured paper on the ceiling. refurbishment also included the first floor dining room.

Their refresh of the Champion pub did get some criticism as there were views that it was returning to Victorian design themes. The early 1950s were a time when design and architecture were looking at more modern forms, typified in the themes and designs used for the 1951 Festival of Britain.

The early 1950s update to the pub included plain and frosted glass on the external windows, not the remarkable, stained glass windows that we see today. These are the work of Ann Sotheran, and were installed in 1989.

They feature a series of 19th century “champions”, with figures such as Florence Nightingale and the cricketer W.G. Grace.

On a sunny day, these windows are very impressive when seen from inside the bar:

The missionary and explorer David Livingstone:

Newspaper reports mentioning the Champion cover all the usual job adverts, reports of crime and theft etc., however I found one interesting article that hinted at what the inside of the pub may have been like in the 1870s.

In September 1874, the Patent Gas Economiser Company held their first annual general meeting, where they reported that they had installed 50 lights in the Champion. Seems a rather large number, but spread across three floors, entering the pub in the 1870s would have been entering a reasonably brightly lit pub, with the hiss of gas lamps and the associated smell of burning gas.

The same report also mentions that the company had installed 1000 lights at the Royal Polytechnic Institution in Regent Street, 600 lights in the German Gymnastic Society in St Pancras Road, and 50 lights in the Hotel Cavour in Leicester Square.

To the left of the Champion pub, along Wells Street, building work is transforming the building that was here, and is adding additional floors to the top, which partly obscures the view of the BT Tower from further south along the street:

There was one further site that I wanted to find, and this required a walk west, along Eastcastle Street.

Eastcastle Street was originally called Castle Street, a name taken from a pub that was in the street. The name change to Eastcastle Street happened in 1918. I cannot find the reason for the name change, but suspect it was one of the many name changes across London in the late 19th / early 20th centuries, to reduce the number of streets with the same name.

At 30 Eastcastle Street is this rather ornate building:

Dating from 1889, this is the Grade II listed Welsh Baptist Chapel, the main church for Welsh Baptists in London.

Eastcastle Street is a mix of architectural styles. Narrow buildings that retain the original building plots, buildings with decoration that does not seem to make any sense, and rows of the type of businesses that frequent the streets north of Oxford Street.

At the end of Eastcastle Street is the junction with Great Titchfield Street and Market Place:

In the above photo, Great Titchfield Street runs left to right, and the larger open space opposite is part of Market Place.

The name comes from Oxford Market, a market that originally occupied much of the space around the above photo, with the market building on the site of the building to the left, and the open space in the photo being part of the open space around the market building.

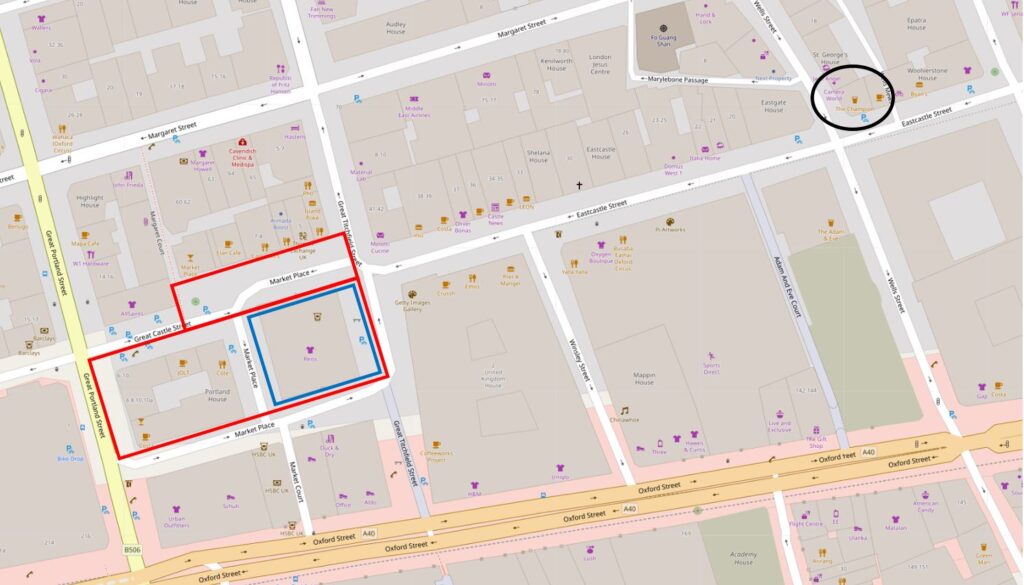

in the following map, the Champion pub is circled to the upper right. On the left of the map, the blue square is where the market building of Oxford Market was located, the red rectangles show the open space around the market with the upper rectangle being where the open space can still be seen today (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

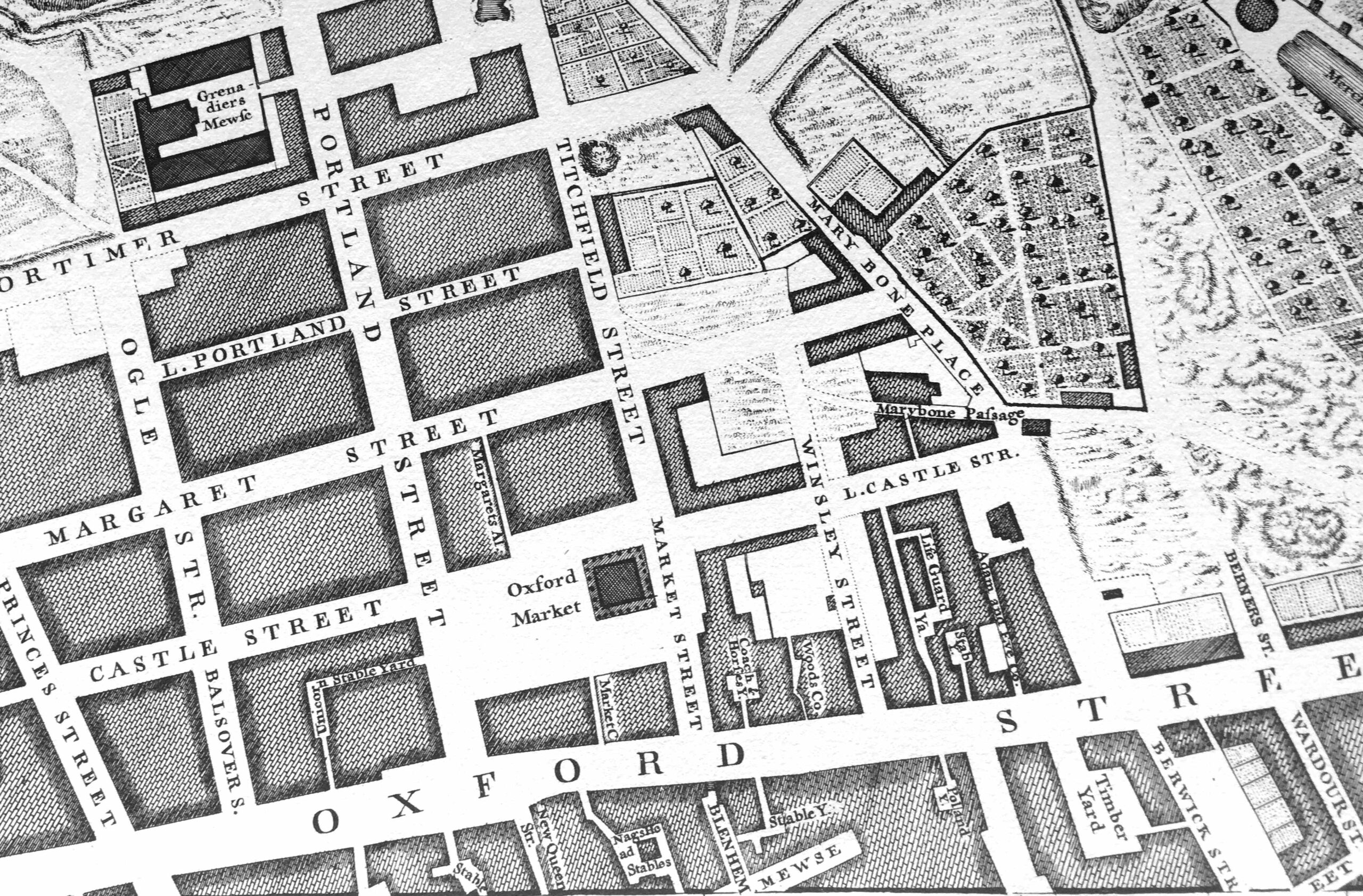

Rocque’s map of 1746 shows Oxford Market, just north of Oxford Street:

Oxford Market had been completed by 1724, however the opening was delayed as Lord Craven, who owned land to the south of Oxford Street feared what the competition would do to his Carnaby Market, however Oxford Market was finally granted a Royal Grant to open on Mondays, Wednesdays and Saturdays.

The market was built to encourage activity in the area, as the fields to the north of Oxford Street were gradually being transformed into streets and housing.

The market took its name, either from Oxford Street to the south, or more likely, Edward, Lord Harley, the Earl of Oxford who was the owner of the land on which the market was built as well as much of the surrounding land.

Harley had come into possession of the land through his wife, Lady Henrietta Cavendish Holles, who was the only child of John Holles, the Duke of Newcastle, the original owner of the farmland around Oxford Street.

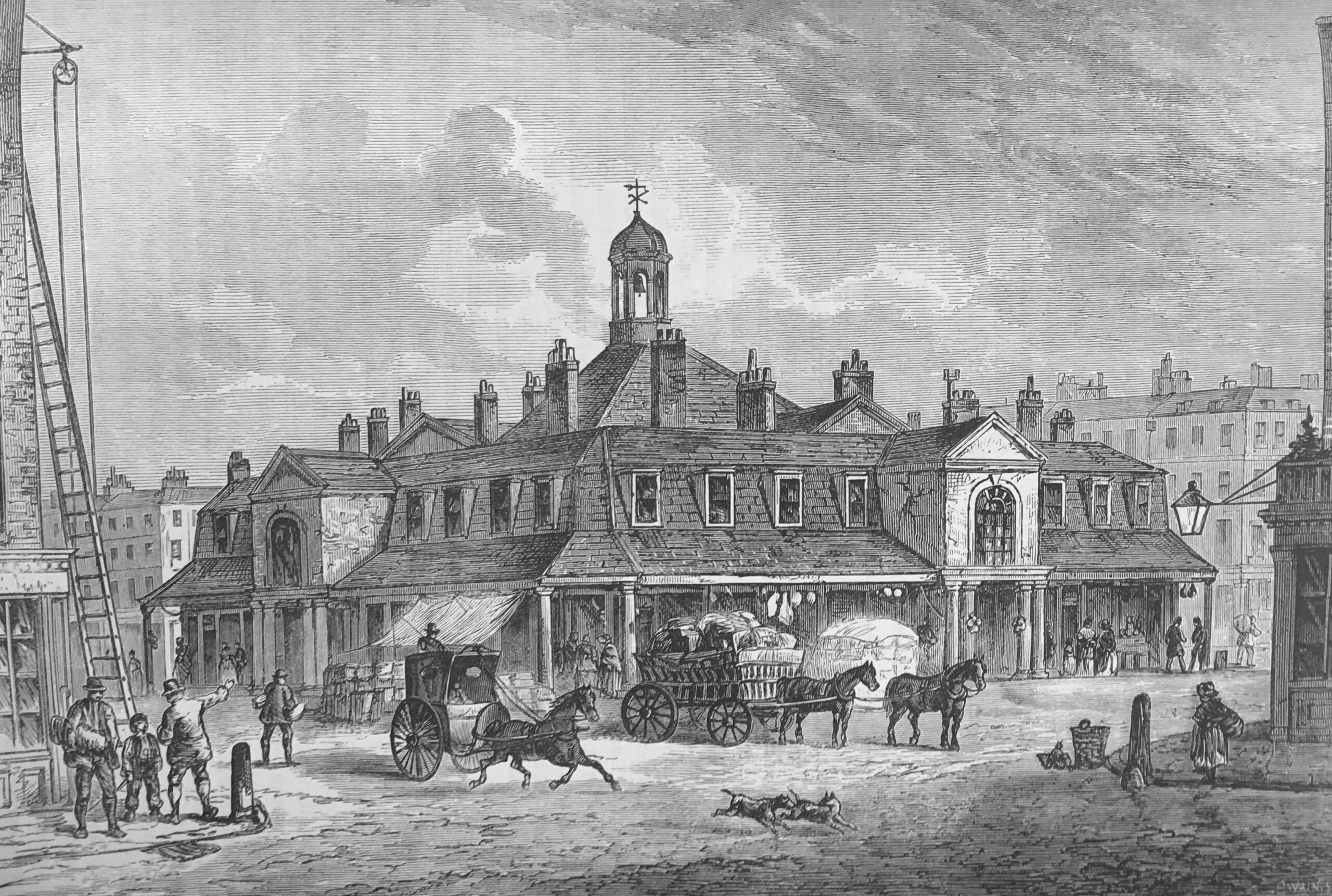

The original market buildings were of wood, and the market was rebuilt in a more substantial form in 1815. The following view of the second version of Oxford Market comes from Edward Walford’s Old and New London:

We can get a view of what was for sale at Oxford Market from newspaper reports:

- February 8th, 1826 – john Wollaston & Co were selling their Gin in quantities of no less than 2 gallons at a price of 15 shillings per gallon

- January 20th, 1824 – A “Great Room” of 45 feet square in the interior of the market was being advertised as being suitable for upholsterers, warehousemen and flower gardeners. The room was fitted with an ornamental stone basin and fountain and was suited for a flower garden

- April 25th, 1841 – The Oxford Market Loan Office was advertising loans of Ten Guineas, Ten and Fifteen Pounds, which could be had from their office at the market

- May 18th, 1833 – Rippon’s Old Established Furnishing Ironmongery Warehouse was advertising Fire Irons, Coal Scuttles, Knives and Forks, Metal Teapots and Tea Urns for sale from their warehouse at the market

- December 15th 1827 – The lease of a Pork Butcher and Cheesemonger store at the market was being advertised. The store had been taking in £3,800 per year

- June 27th, 1801 – Several lumps of butter, deficient in weight, were seized by the Clerks of the Oxford Market and distributed to the poor

So traders in the Oxford Market were selling a wide range of products, butter, pork, teapots and coal scuttles, flowers and gin, and you could also take out a loan at the market.

Nothing to do with Oxford Market, however on the same page as the 1801 report of butter being seized, there was another report which tells some of the terrible stories of life in London:

“Wednesday were executed in the Old Bailey, pursuant to their sentences, J. McIntoth and J. Wooldridge, for forgery, and W. Cross, R. Nutts, J, Riley and J. Roberts, for highway robbery. The unfortunate convicts were all men of decent appearance, and their conduct on the scaffold was such as became their awful situation.

Some of the above prisoners attempted on Monday to make their escape from Newgate through the common sewer – they explored as far as Milk-street, Cheapside, when the intolerable stench and filth overpowered their senses; with great difficulty they found their way to the iron-grating and intreated by their cries to be liberated. assistance was immediately procured, when they were released without much difficulty.”

These two paragraphs say so much: that you could be hung for forgery, the statement that their conduct on the scaffold was “such as became their awful situation”, and their desperation in seeking an escape via the sewer. Milk Street is roughly 568 metres from the site of the Old Bailey so they had travelled a considerable distance in an early 19th century sewer.

Back to Oxford Market, and the following view is looking down Market Place towards Oxford Street which can be seen through the alley at the end of the street:

In the above photo, the market building was on the left, and open space in front of the market occupied the space where the building is on the right, the corner of which is shown in the following photo. The block was all part of the open space in front of Oxford Market.

Oxford Market was never really a financial success. For a London market it was relatively small which may have limited the number of suppliers and the range of goods available.

By the late 1830s, part of the market had been converted into offices from where out-pensioners of Chelsea Hospital were paid.

The market buildings was sold in 1876, demolished in 1881, and a block of flats built on the site.

Although Oxford Market is long gone, the street surrounding three sides of the old market building is still called Market Place, and the footprint of the building, and the surrounding open space can still be seen in the surrounding streets, and the wider open space and restaurants along the northern stretch of Market Place.