It Can Now Be Revealed – not a tabloid headline but the title of a booklet printed in 1945 by the British Railways Press Office telling the story of the railways during the war and ending with hopes for a brighter transport future. This booklet was one of many that were issued in the immediate years after the 2nd World War by organisations such as the Railways, the Post Office, the Police, all the various branches of the armed forces, individual London boroughs along with towns and cities across the country.

My father bought a number of these as they were published and they make fascinating reading and give the impression of an urgent need to record what happened between 1939 and 1945 before the country quickly moved on to reconstruction and the hoped for brighter future.

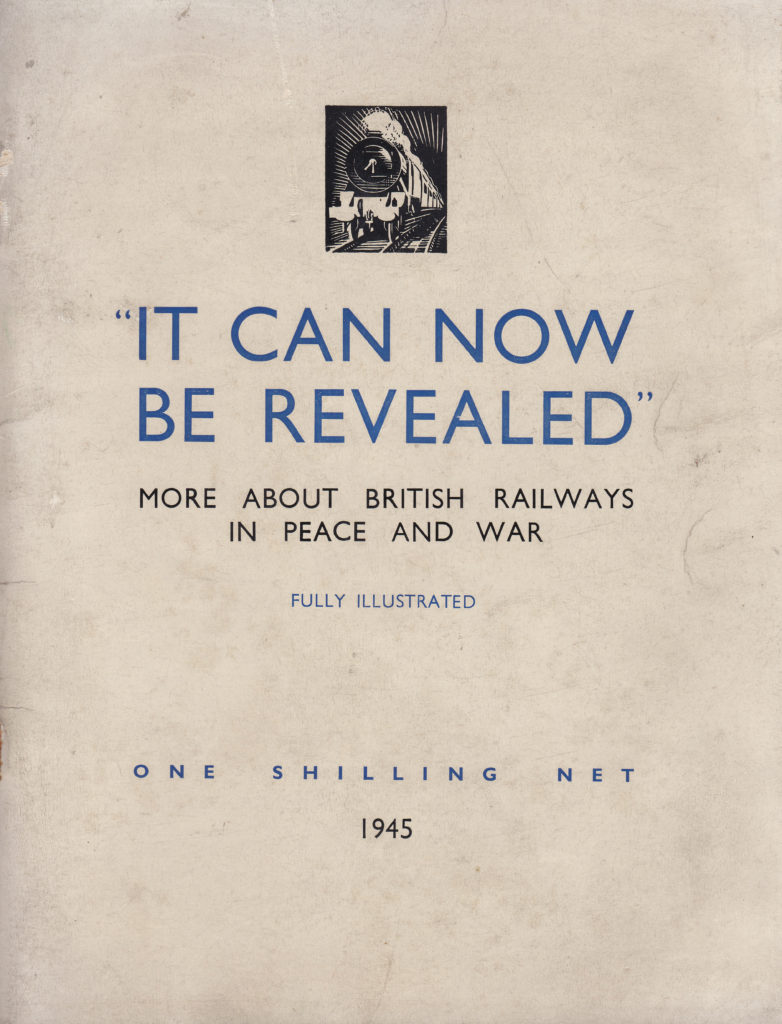

For this week’s post, I would like to introduce two of these booklets: The Post Office Went To War, and to start with, the title of the post – It Can Now Be Revealed, More About The British Railways In Peace And War:

It Can Now Be Revealed has three main themes: how the railways contributed to the war effort, how the railways responded to the damage inflicted by bombing and a look to the future. In covering the railways, the booklet fully covers the London Transport Passenger Board where workshops and staff quickly moved from supporting London’s transport network to the manufacture of components and equipment for the war effort.

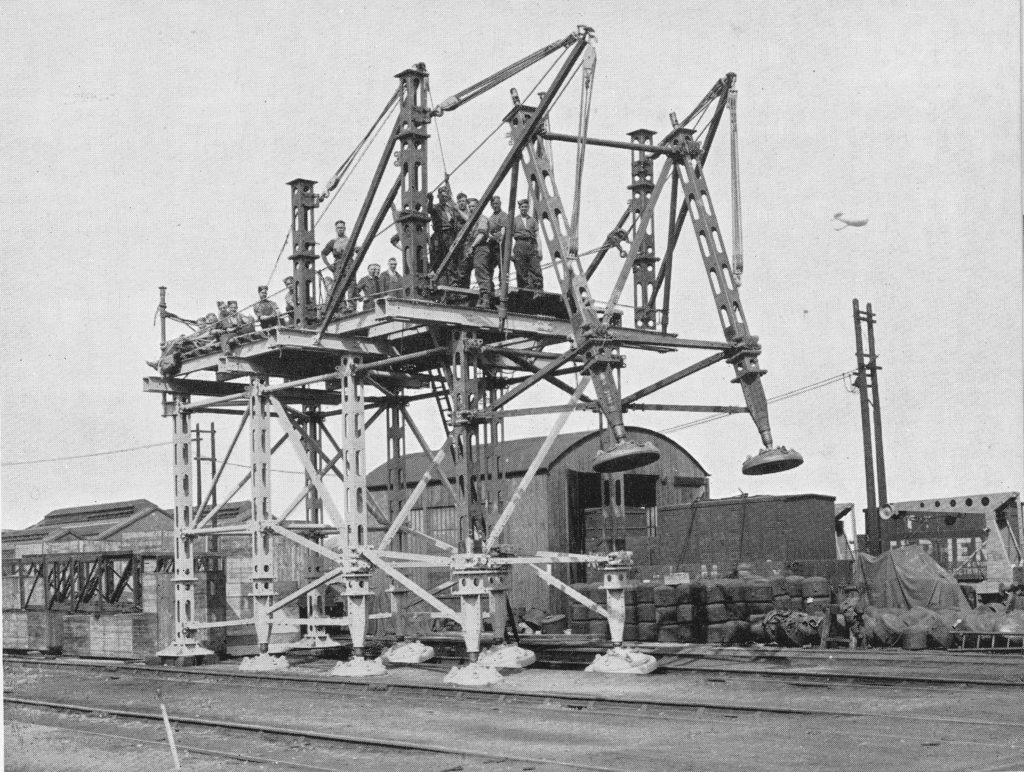

Pre-war, the rail network and the London Passenger Transport Board all had considerable engineering and manufacturing resources and these were immediately converted into wartime production. During the almost six years of war, these resources produced vast amounts of equipment of all types covering bombs, guns, boats, tanks, gliders and some very specialised equipment. The following photo shows one such item of specialised equipment produced by the Railway and London Transport workshops – a machine to help with the repair and installation of bridges.

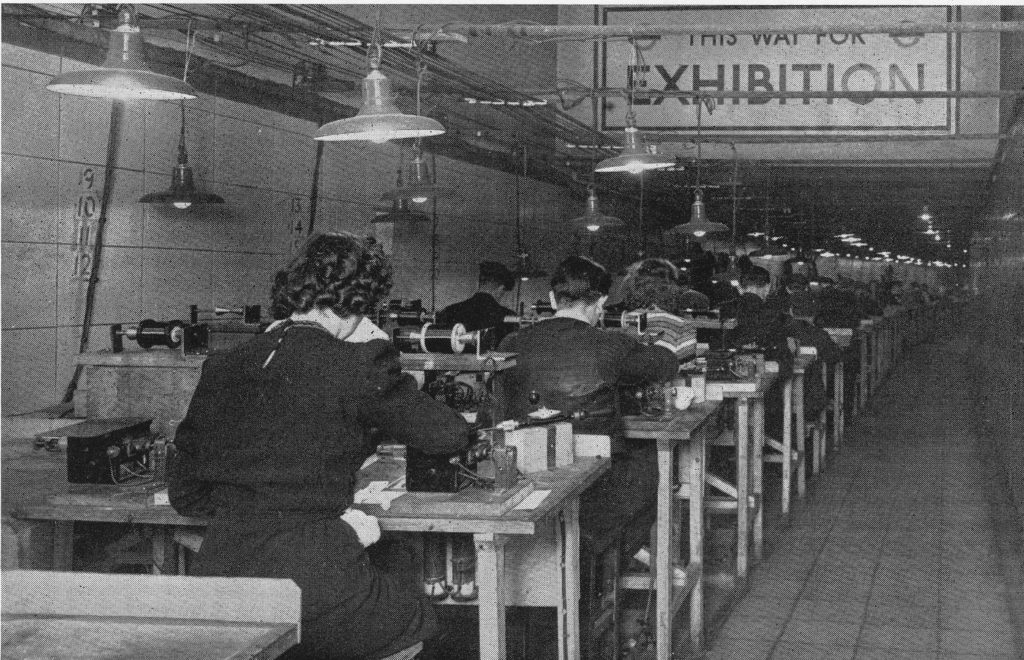

London Transport, along with a number of road transport concerns, was part of the London Aircraft Production Group. The Group rapidly set up manufacturing resources and within fourteen months the first aircraft manufactured by the Group took flight and by the middle of 1944, the London Aircraft Production Group had built 503 Halifax bombers.

London Transport were able to make use of underground facilities for the secure manufacturing of aircraft components. The following photo shows once such production facility:

To give some idea of the breadth of equipment manufactured by London Transport, from the outbreak of war to 1944, London Transport had manufactured: 8,000 forgings for guns, 20,000 gun components, 80,000 sea mine components, 102,000 road vehicle parts and 158,000 2 inch shells as well as aircraft, bridges, tanks etc.

Transporting staff to the Railway and London Transport factories was a major effort as well as maintaining a degree of normal services. London’s buses were used for factory transport as well as continuing to provide services across the city and during the periods when bombing was at its peak there was considerable disruption with crowding on many of the routes across the city.

In the build up to war there was a considerable amount of planning and preparation to provide the staff of the rail networks with the equipment needed to protect the system and to install equipment to prevent damage. A serious concern with the London Underground system was the risk of flooding. This was a very real risk if the Thames embankment was breached or if bombing damaged water mains or sewers.

Floodgates were installed at a number of underground stations, including Waterloo, Charing Cross and the Strand stations. These were electrically operated floodgates installed across tunnels and connecting passages. The following photo shows one of the gates being tested at Charing Cross station.

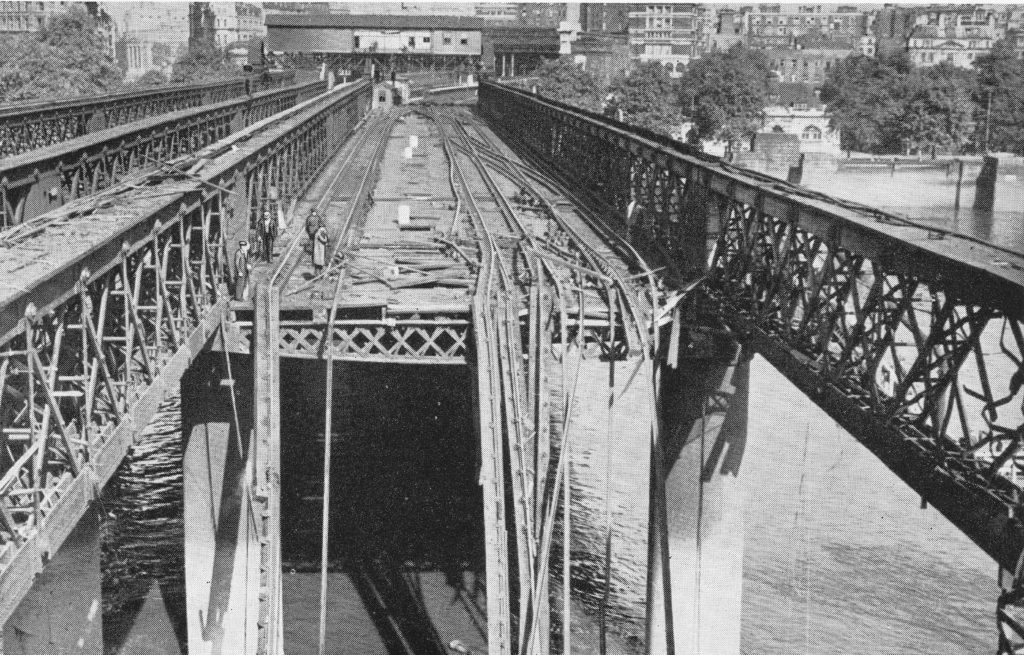

The booklet recorded many of the incidents of damage across the rail network and the efforts that went in to restore the rail network as quickly as possible. Damage across the network was considerable, from the earliest days of the war through to the V1 and V2 weapons with both the above ground and underground networks suffering.

The booklet records an example of what happened when a V1 fell on the rail network:

“One of the worst incidents happened in the Southern. One night in August an express from Victoria bound for the Kent coast was travelling at 60 miles an hour when the girders of a bridge over a country lane less than 200 yards ahead of the train were damaged by a flying bomb falling nearby. The driver saw the explosion and at once threw on the brakes, but before he could bring the train to a stand it had reached the bridge, which collapsed when the engine, tender and leading coach had passed over. As a result the engine and tender were derailed about 100 feet from the bridge and the two first coaches were flung at right angles to the track. the third vehicle in the train got across, together with the leading end of the fourth, which came to a rest spanning the gap and supported on the damaged abutment. In the road beneath were poised four bogies torn from coaches. Eight persons, including a permanent way man who was on the bridge at the time, were killed and sixteen seriously injured, but strenuous efforts on the part of the railway engineers prevented serious dislocation to traffic. The damaged rolling stock was removed and a temporary bridge of two spans of 50 feet girders speedily erected, the outer ends of the girders being supported by bearing pads on the approach embankments and the centre by a steel trestle built in the middle of the roadway with the aid of a mobile crane. The relaying of the tracks was then quickly completed and within 66 hours of the incident both lines were again open for traffic.”

Which certainly brings the challenges of today’s commute into context.

Photos within the booklet show the considerable damage across the rail network including the following photo showing damage to the Hungerford railway bridge, taken from the southern end of the bridge looking north towards Charing Cross station.

The booklet concludes with a positive view of the future with the final chapter opening with the sentence “The British Railways and London Transport are determined to regain and surpass their peacetime standards of public service”.

This included plans for new stations and rolling stock. This was urgently needed as there had been hardly any new building during the war years and the rail and underground networks were suffering from pre-war infrastructure, wartime damage and temporary repair and minimum maintenance.

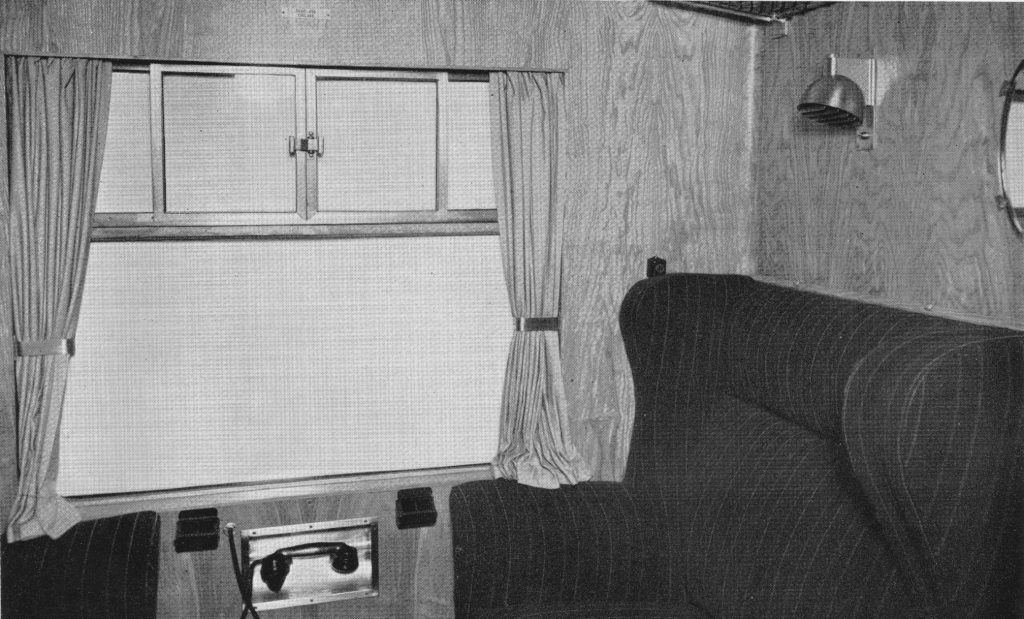

The following photo shows an example of new carriage construction and the title to the photo highlights one of the benefits being “improved lighting”.

Along with a presumably a new design of first class compartment judging by the telephone handset below the window, presumably so that a first class passenger could call for service.

As well as new rolling stock, the booklet looked forward to new stations that would be built in the post war period. The station was described as the “shop” in which railway transport is sold. The booklet describes the facilities that will be provided at these new stations:

“The future British railway station will incorporate as spacious a concourse as possible, equipped with all the facilities that passengers need, conveniently situated and easily identifiable. Both concourse and public rooms will be light, cheerful and attractively decorated. News theatres (no idea what these were), newsagents, fruiterers, chemists, confectioners shops and Post Office facilities will be included whenever needed. Special attention will be given to the standard of food, drink and service provided in the refreshment rooms. Finally the platforms will be kept as free as possible of obstructions and passengers given the clearest indication and guidance about their trains, and how to get to them, by means of carefully designed train indicators and signs, supplemented by loudspeakers.”

The booklet includes a drawing of one of the future stations, Finsbury Park which will be rebuilt “on the most modern lines”.

It Can Now Be Revealed provides a fascinating insight into the impact of the last war on the rail networks of London and the wider country and how every aspect of the railway network and those who worked on the network were involved in one way or another in the war effort. As with many publications of the later years of the war, the booklet is also looking forward to a much brighter future with reconstruction offering the chance to significantly improve all aspects of the rail network.

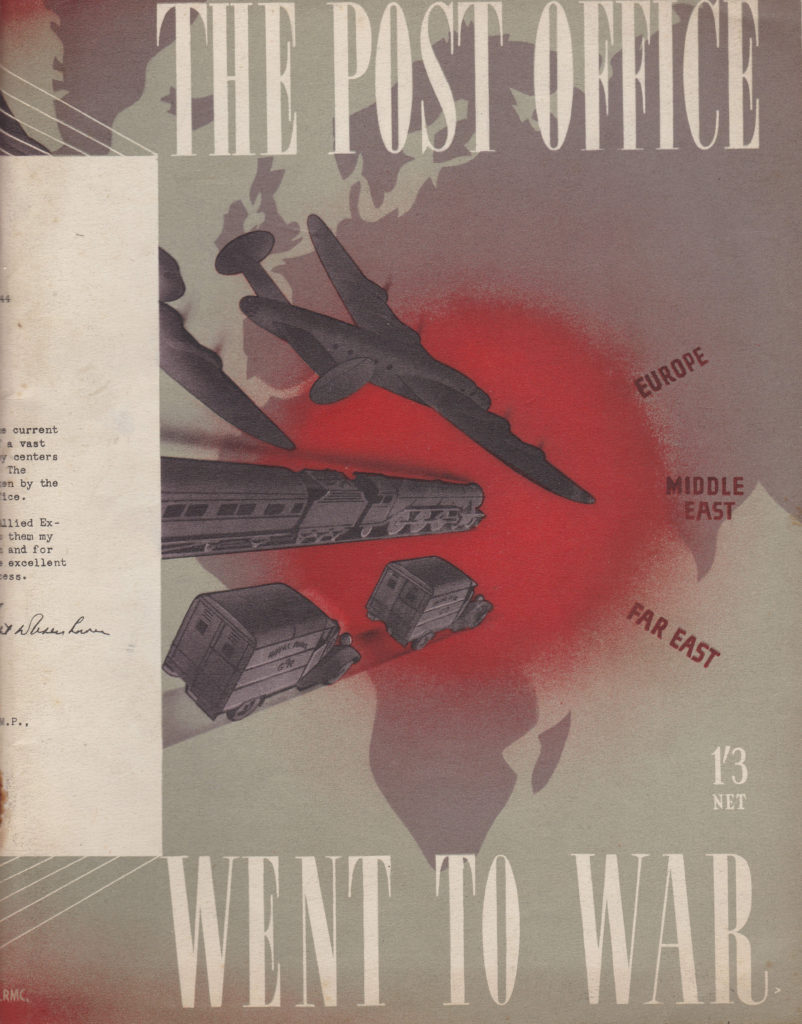

The second booklet was published a year later in 1946 and titled “The Post Office Went To War”. This was in the days when the Post Office ran a wide range of services, not just letter and parcel delivery, but also the telephone and telegraph networks, radio stations for long distance calls, sub-sea cables etc.

The extra year before publication may have allowed time for some additional graphic design as the Post Office booklet has a more interesting layout and artwork then the earlier Railways booklet published in 1945.

The opening paragraph to Chapter One states “Throughout our history as a nation it has been our cheerful habit to declare war first and then to prepare for it”, a statement that could also apply to events over the last few decades.

The challenges that faced the Post Office started long before there was any enemy action. Within the first week after war was declared, the Post Office lost fifteen percent of staff to the Forces, immediately having an impact on the ability to continue to provide services.

The first few months of war were spent putting in new telephone circuits to coordinate the services that would defend the country, and implementing alternative circuit routing so damage to one site would not cut out a large number of critical services.

When the bombing of London started, the impact was considerable. In one night alone in September 1940, twenty-three London Post Offices were hit and damage to the road and railway networks caused many problems with the transport of mail.

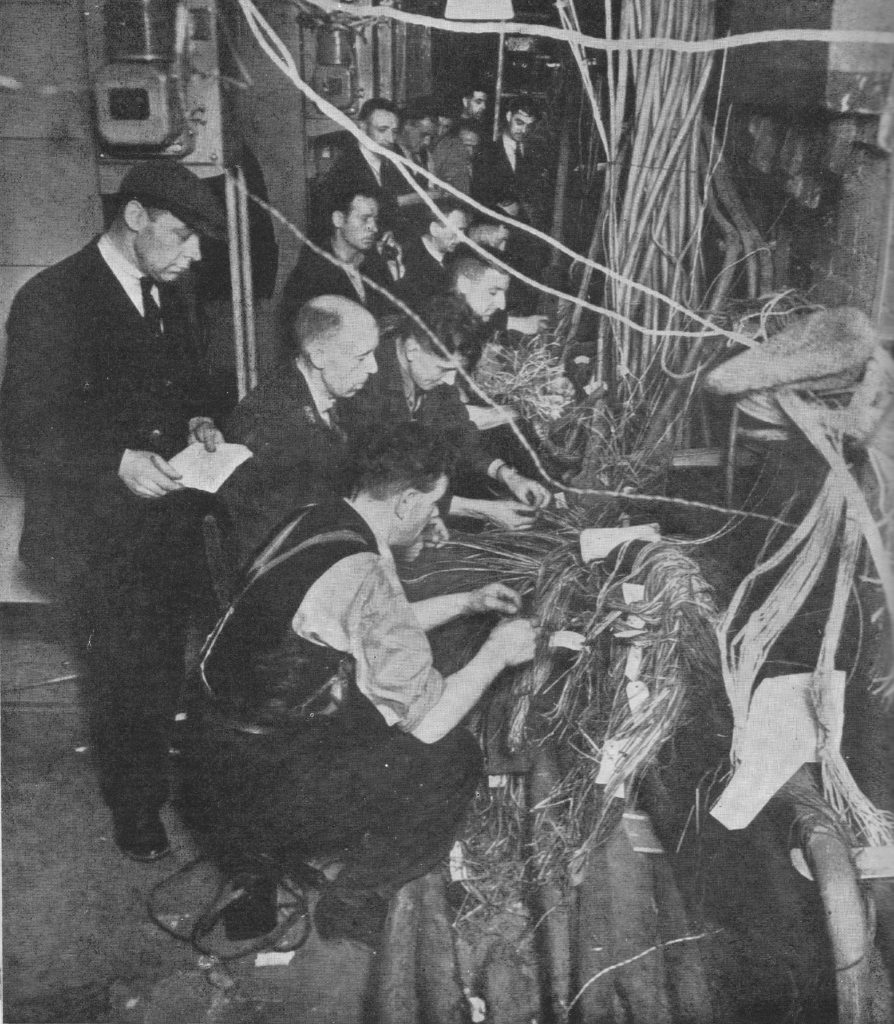

London was also a hub for much of the country’s telephone network with most of the international circuits terminating in a key number of London Telephone Exchanges. Bombing could damage cable at multiple points across the city, not just in the Exchanges, but also where they ran along the streets. After bombing it was an ongoing battle to quickly reconnect damaged cables to get telephone and telegraph services back up and running. Cables would be cut and fire would cause the lead cover and insulation to melt and burn away

The following photo from the booklet shows a team of engineers working on reconnecting damaged cables, and is titled “Joining up after a raid”.

The Post Office services hosted in London could not easily be moved out of the city. For telephone and telegraph services, the country network was design so that the majority of long distance and international calls were routed through a small set of London buildings. it was not just relocating staff from these buildings but also reconfiguring the whole network and implementing a new cabling system that would have been required to move out of London. The majority of these key services remained in central London buildings.

One of these was the Wood Street building, just north of Cheapside. This building housed three large automatic telephone exchanges, London Wall, Metropolitan and National along with Exchange services for City and Central areas. Wood Street also housed a large operator service.

On the night of the 29th December 1940, this area was very badly damaged by bombing. The building continued to operate throughout the night with operating staff working at an emergency manual switchboard in the basement of the building.

At 7pm a high explosive bomb fell close to the building blowing in all the doors and windows and the fires from the numerous incendiary bombs reached parts of the building overnight.

15,000 telephone lines terminated in Wood Street and the following morning 10,000 of these needed repair. The building itself was also badly damaged with the following photo showing one of the burnt out operator halls with the remains of operator positions lining the walls on either side.

In the days that followed, as well as work to repair the building, equipment and cabling, one hundred telephone boxes were installed along Cheapside and Moorgate to provide temporary services.

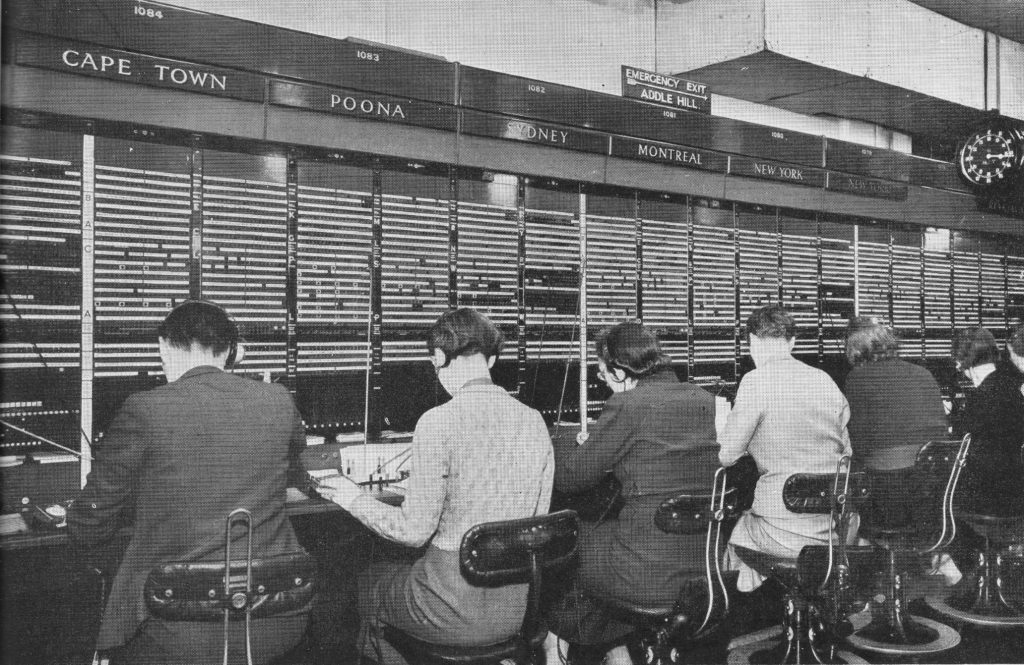

What the operator hall should have looked like is shown in the photo below taken in the Faraday Building in Queen Victoria Street which was a hub for Trunk and International telephone services and thankfully did not suffer the same level of damage as other telephone exchanges in the city.

The following two photos show the impact of a high explosive bomb falling in the road outside the Central Telegraph Office in King Edward Street.

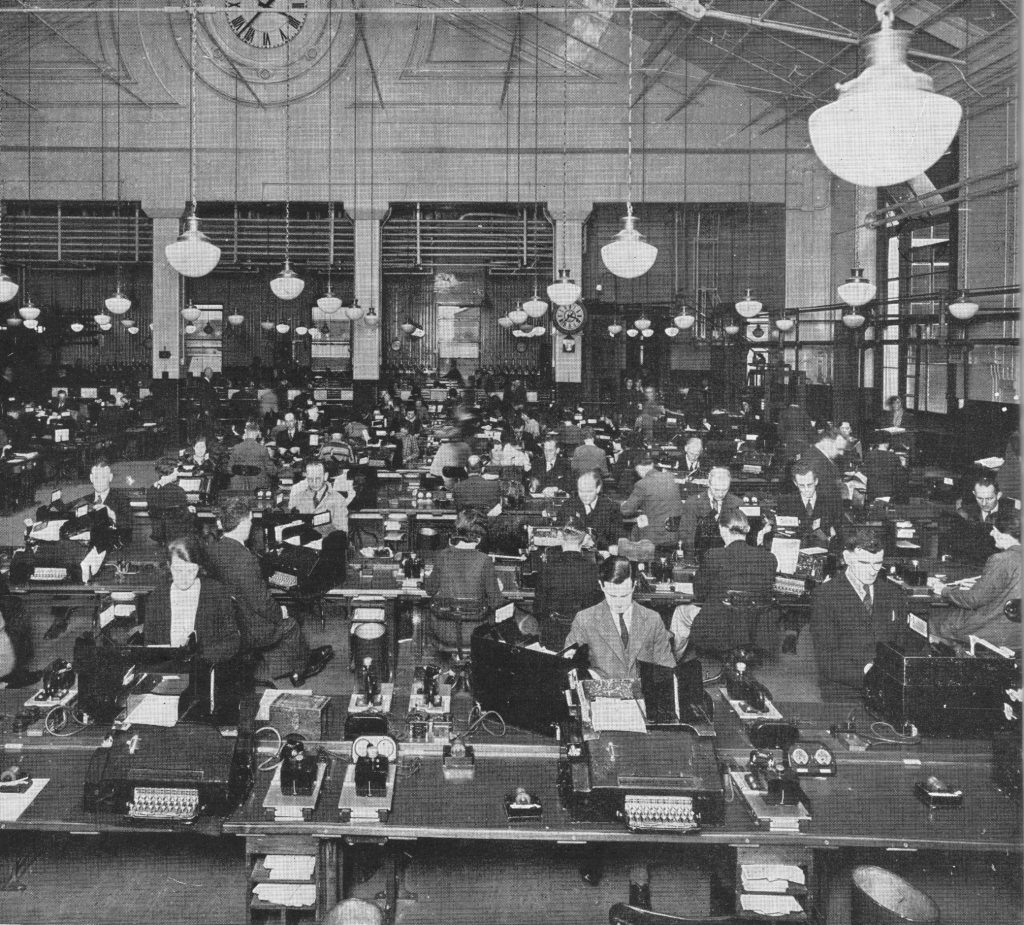

The Central Telegraph Office was the heart of the whole British telegraph system (used to transmit telegrams) and had a staff of 3,000. A telegram was how you would send a fast written short message to someone, the early 20th century version of text messaging or Whatsapp. Written messages would be delivered or phoned in to the Central Telegraph Office, typed onto a teleprinter that would send the message to a similar machine at a location closest to the recipient where it would be printed out and hand delivered.

The Central Telegraph Office had galleries dedicated to Inland and Foreign telegrams. The Inland Gallery was equipped with 500 teleprinter machines dealing with 200,000 telegrams a day.

The Central Telegraph Office was completely gutted over the night of the 29th December 1940, but was rebuilt and continued to provide service during the later years of the war. The following photo shows one of the galleries in operation.

One of the methods to send a telegram for the businesses in the City was to phone the Central Telegraph Office and dictate the message, however with the damage to telephone cables, this was not always possible, so the Post Office stationed Telegraph Messengers at key points across the City to pick up messages and take them to the Central Telegraph Office.

As well as telephones and telegrams, the Post Office was also responsible for the collection and delivery of letters and parcels and in London this centered on Mount Pleasant which at the time was described as the largest Post Office in the World and just prior to the start of the war employed up to 7,000 Post Office workers.

The size of Mount Pleasant was such that it was bound to be hit by bombs but did get off relatively lightly being hit nine times throughout the war years, although some of these did cause considerable damage including a single bomb that on the 18th June 1943 completely gutted the three storey parcels building.

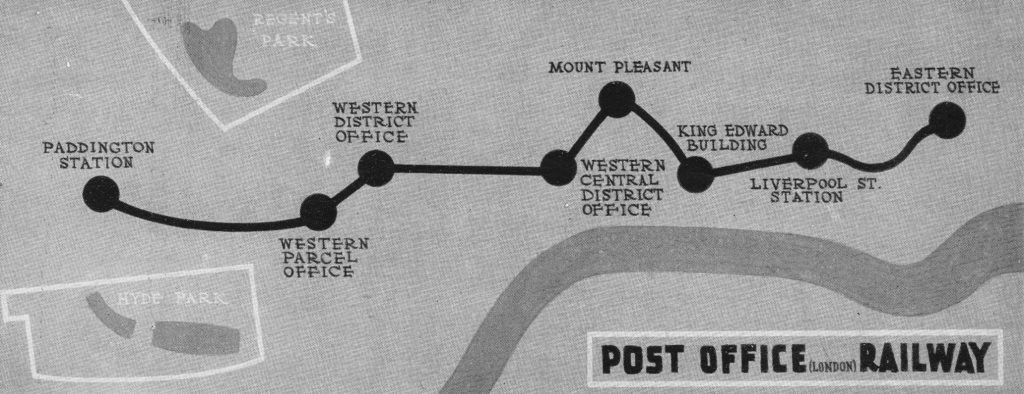

The Post Office Railway passes through Mount Pleasant and the booklet describes the railway during the war:

“During the war the Post Office Railway , in addition to its normal duties, made its own contribution to the Post Office war effort. It furnished an admirable air-raid shelter and dormitory; a series of cots, hinged to the wall by one end, being pulled down and set right across the track when the long day’s work was done and the conductor rail had gone dead for the night.

It was also a minor casualty when in December, 1944, a V2 rocket bomb fell in Bird Street, between Selfridges and the Western District Parcels Office. Besides putting this important parcels office out of action just before Christmas, it damaged a water-main which flooded the station of the Western District Parcels Office, nearly 80 feet below to a depth of 18 inches. But the Post Office Railway is prepared for such emergencies, and the station was soon pumped clear.”

Map from the Post Office booklet showing the stations of the Post Office railway:

An interesting couple of paragraphs in the booklet show that even in wartime, the collection of customs duties was fully in force:

“In war-time one class of parcel presents a particular problem – namely the packets of tobacco and cigarettes which may be dispatched duty-free to our Forces overseas. These are convenient to send, for all you have to do is hand an address and the requisite sum across a tobacconists counter, and a standard packet will be dispatched to your own particular sailor, solider or airman.

But if, as frequently happens, the packet cannot be delivered – possibly because the addressee has become a casualty or been transferred to another quarter of the globe – and the local authority sends it back, the nice question now arises ‘Who is to have the packet?’ Not the tobacconist for he has already been paid; nor the sender, for he has paid no duty. The Post Office solves the problem by handing over the packet to the customs authorities.”

The booklet also contains some fascinating detail of wartime mail distribution. It was possible to send letter to members of the British forces who were held as prisoners of war. An agreement was reached with Germany in 1941 allowing letters to be flown out to Lisbon where they would be handed over to the German airforce who would also hand over letters for German nationals held prisoner of war in the UK. Over 200,000 letters were sent each week from London to Lisbon for onward routing to British prisoners of war.

The booklet highlights the difficulties in maintaining the overall delivery of Post Office services, whether it was due to bombed Post Offices, damaged cabling or disruption to transport networks. Even when trying to repair the network, the impact of bombing can continue to cause problems. The following photo shows a cable drum blown from the street to the top floor of a house as a result of a bomb.

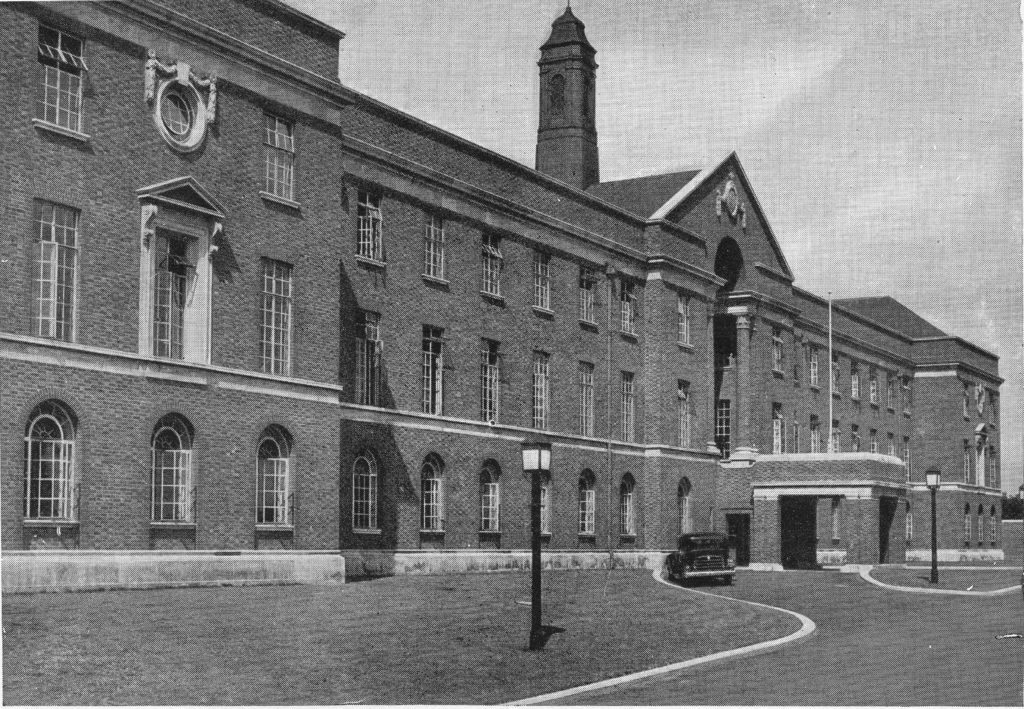

Unlike the Railway booklet, the Post Office Went To War does not have a chapter looking forward to post war reconstruction, however it does have a section on research and features the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill in north-west London.

Dollis Hill was the main Post Office Research Station and carried out research into all the technologies used by the Post Office including Telephone Systems, Radio, Cables, Sub-Sea systems etc. A significant number of engineers and scientists were employed at Dollis Hill with, for example, a staff of 300 in just the Radio Section.

It was still classified information at the time the booklet was written so it was not included, however the Collossus computers used at Bletchley Park during the war to decode German signals were built at Dollis Hill. Tommy Flowers (originally from Poplar in east London) who worked at Dollis Hill proposed using electronic valves rather than mechanical relays to build the computers needed by Alan Turing at Bletchley and despite considerable resistance that a machine with such a large number of valves (1,500 upwards) would be reliable, Tommy Flowers and his team constructed the Collossus computers which more than confirmed Flowers’ view that they would be much faster and more reliable than the existing mechanical relay based systems.

The Dollis Hill Research Station:

The Research Station moved out of London to Martlesham Heath in Suffolk during the 1970s after which Dollis Hill closed. The main building was preserved and converted into flats.The approach road to the flats has been named Flowers Close in honour of Tommy Flowers.

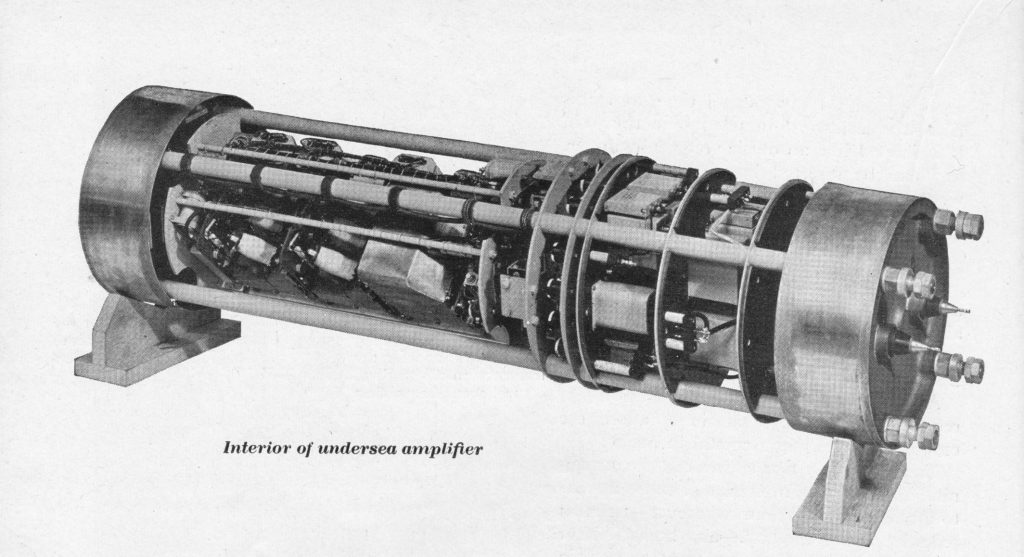

From the booklet, a photo of the interior of an undersea amplifier developed at Dollis Hill and used on sub-sea cable systems to amplify signals enabling telephone calls and telegrams to be sent over very long distances.

These two booklets, along with the many others published in the same period have a common theme. Recording with pride how their respective organisations, London boroughs or towns contributed to achieving victory at the end of the war, but also a recognition that times would very soon change and these events needed to be recorded quickly before the country focused on reconstruction and the possibilities that the future would bring.