Today, we take electricity for granted, however in the history of London it is only comparatively recently that the city has been lit and powered by electrical power.

The old power station at Bankside has been transformed to Tate Modern and the power station at Battersea is finally undergoing a major redevelopment, however before these two well known landmarks powered the city, there were a number of smaller stations built at the start of London’s electrical age at the end of the 19th century.

My grandfather worked in one of these during the 1930s and 1940s. I never met him as he died long before I was born, however I have always been interested in discovering where he worked and if I could find any history of the power station.

The site he worked at was the Regent’s Park Central Station, an unlikely name for such an industrial activity, but at the start of electrical generation in London, the technology available only supported small scale, local generation and there was a need for a station that could serve the area to the east of Regent’s Park.

The Regent’s Park Central Station was constructed by the Vestry of St. Pancras, the first local authority in London to start the transfer from gas street lighting to electric and to provide a supply to private consumers. Construction started in 1890 and the station started generating electricity in late 1891. (The Vestry of St. Pancras was the original Parish Administration before the change to a Metropolitan Borough following the London Government Act of 1899)

So where was this power station and what did it look like?

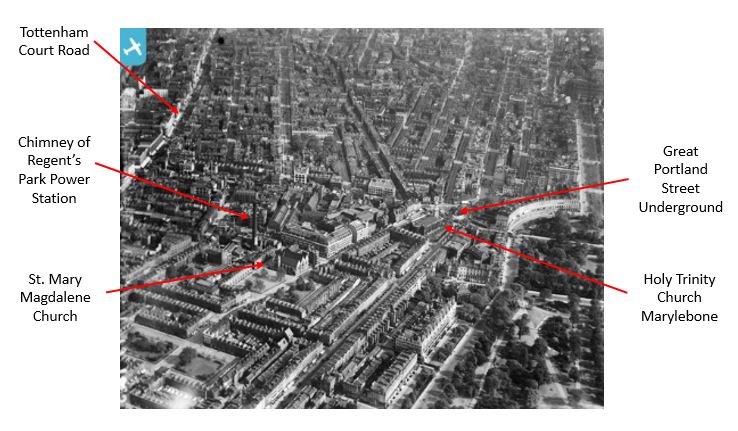

I have been searching a number of archives but have been unable to find any photos of the power station. I have found an aerial view taken by Aerofilms in 1926 which does show the chimney of the power station. See the photo below, the power station can be seen to the left of centre. (Aerofilms link here)

To highlight the location, and to show where it was relative to other landmarks, I have marked some locations in the photo below. The photo has been taken north of the power station, looking south. Tottenham Court Road is on the left, running from the junction with Euston Road away towards Oxford Street at the top of the photo. Regent’s Park can be seen to the right.

I knew roughly where the power station was located as in the accounts written by my father of growing up in London during the war, he referred to the power station being in Longford Street and Stanhope Street, so my next challenge was to see if I could find the location today.

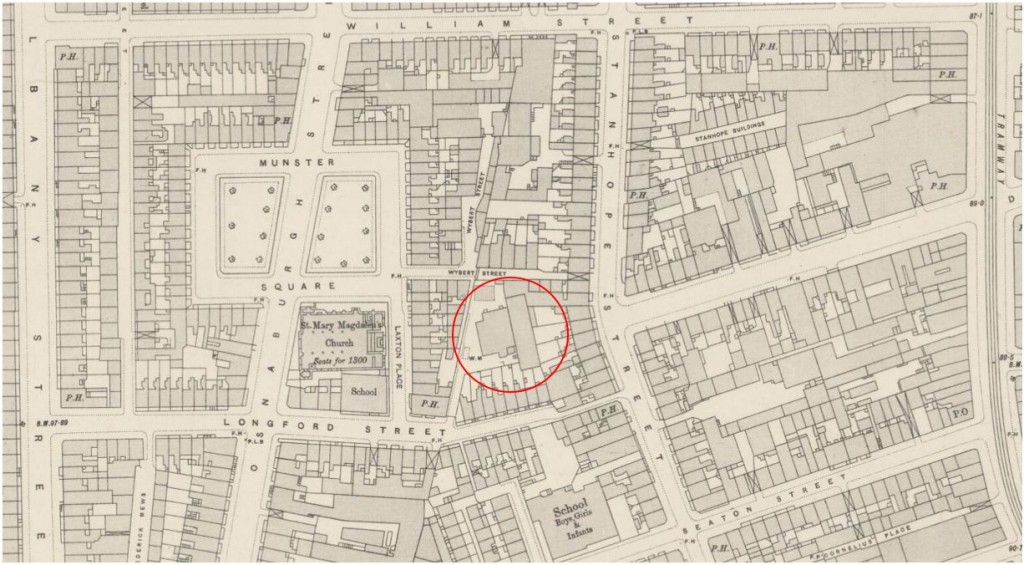

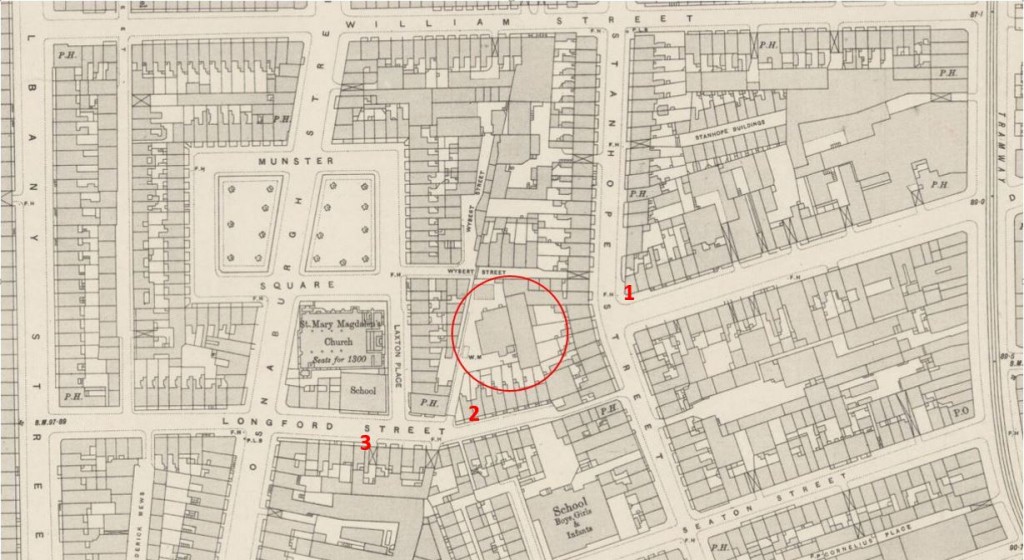

As with much of London, parts of this area have seen some significant change, particularly the major building work that has resulted in the Euston Tower and Triton Square office developments. The following map (Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland) shows the location of the power station, built within an area of land surrounded by houses, bounded by Longford Street and Stanhope Street.

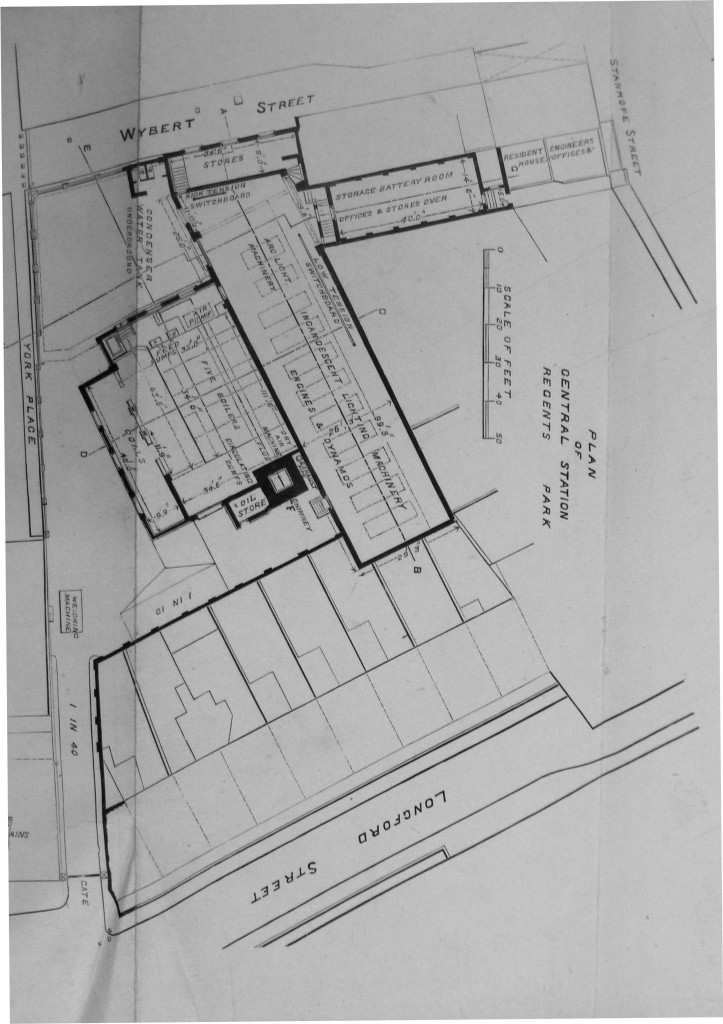

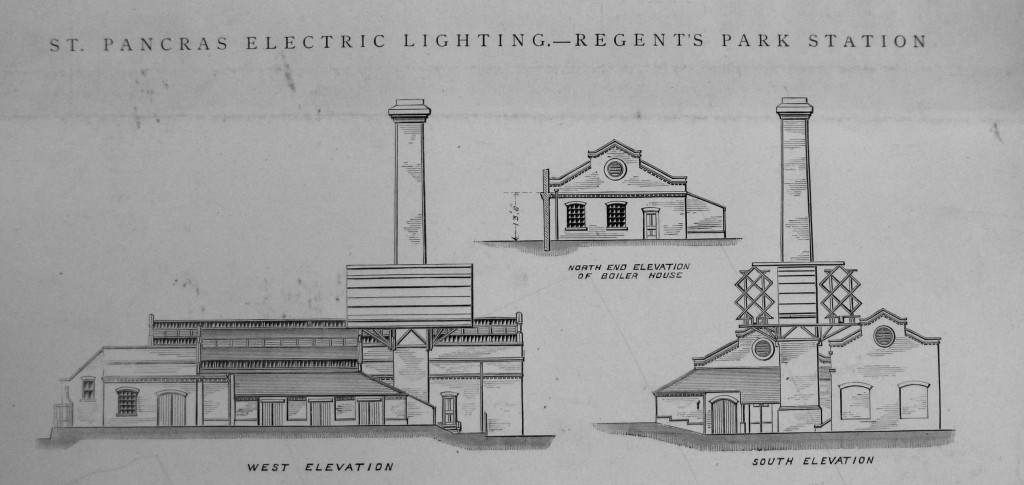

An 1892 issue of The Engineer contains an article about the power station and includes a number of plans and drawings, including the following detailed plan of the power station (I have rotated by 90 degrees to roughly align with the map above).

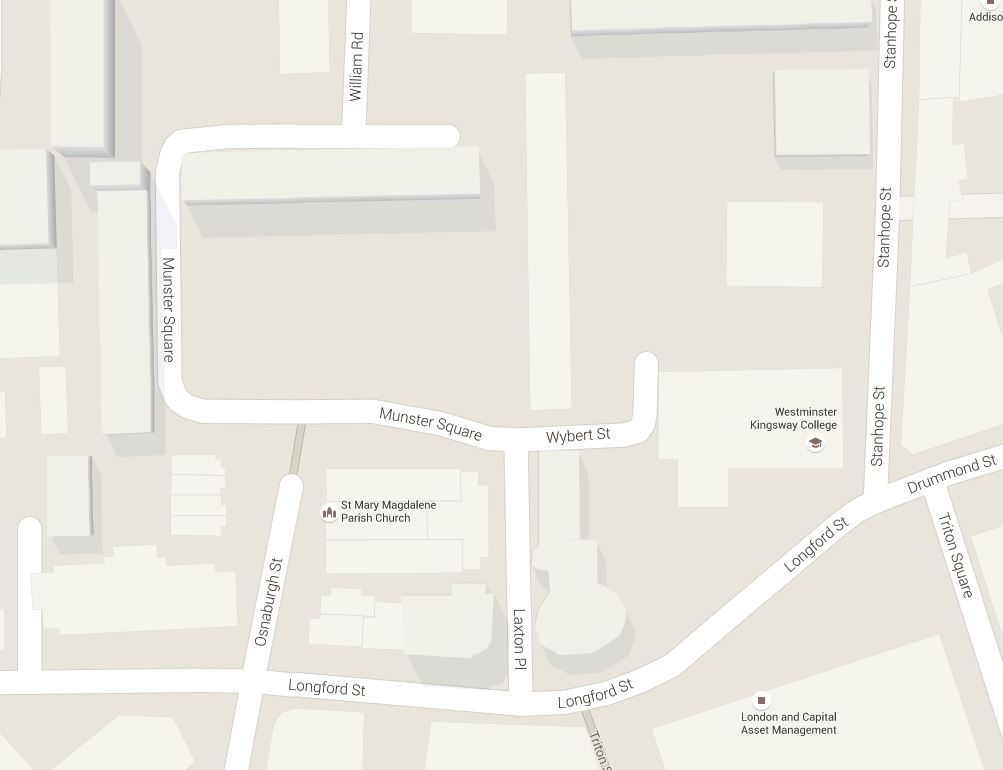

The challenge with locating the site of the power station today is that the routing of Longford Street changed in the 1960s as part of the redevelopment of the area. The following map shows the area today.

Compare this map to the 1895 Ordnance Survey map. In 1895, Longford Street ran straight to Stanhope Street which continued down to the Euston Road. Today, Stanhope Street has been cut off from Euston Road by the Triton Square development and Longford Street now curves up to meet the end of Stanhope Street and Drummond Street. As can be seen from the 1895 map, this curve to get to Drummond Street (the road that is not named to the right of the power station) means that Longford Street now cuts across the lower part of the power station.

Having found the location of the power station and how the streets have changed, it was time to visit the area. I have repeated the 1895 map, and have now marked the approximate positions of where I took the following three photos.

For the first photo, I walked down Drummond Street, and came to the junction with Stanhope Street. This photo is taken from position 1 and is looking down the new routing of Longford Street down towards position 2. Westminster Kingsway College now occupies the site of the power station and the houses that ran along Stanhope Street. The southern end of the power station building housing the engine and dynamos would also have run across the area now occupied by Longford Street.

This photo is taken from position 2, looking across the houses that ran along Longford Street and directly into the power station which occupied the centre and left area of the college buildings with the engine and dynamo building extending onto the road.

And this photo was taken from position 3, standing in the original section of Longford Street, which originally ran straight on. The revised layout with the curve round to the left can be clearly seen.

So what did the power station look like? The “Engineer” publication also included drawings of the power station. In photo 2 above I am looking directly into the South Elevation shown below.

The roof of the power station was constructed from glass panels. In my father’s account of growing up in the area, written just after the last war he refers to this roof. During September and October 1940 my grandfather was working the night shift at the power station. The following is my father’s account of one particularly heavy night’s raid when a land mine landed close to their flat during this time:

“After perhaps two hours, a warden appeared, told us of our miraculous escape from the land mines – we were not yet aware of what had happened – and suggested we should make our way to the nearest rest centre. now that the raid appeared to be easing. However, mother’s priority was to get to see father although the thought of the glass roof and the electrical apparatus under it was not exactly comforting.

Mum said her grateful goodbyes from both of us, then passing through the passageway beneath Windsor House out into Cumberland Market to walk the quarter mile or so to Longford Street. the moon was still there, and from the east came the distant rumbles and flashes in the sky, marking the dying hours of the raid. Neither of us said much and hurried along fearing a sudden blast should the mines explode. The usual smell of smoke, and the far off sound of planes, bells of emergency and fire service vehicles making their way as best they could and hardly anyone around on their feet.

Answering the ringing bell at the generating station gate, father was shocked to see us standing there. He knew from reports that Saint Pancras was being plastered that night, but little else. in the warm again and with dad, more tea and the raid diminishing all the time we slowly made a sort of recovery.”

The power station was built for the Vestry of St. Pancras. A municipal electricity service to provide electrical street lighting and provide power for industry and homes in the local area.

The annual statements for the power station remain and make fascinating reading to understand the process for building a power station in the late 19th century and how quickly the use of electricity was adopted in the immediate area.

The construction of the power station was authorised by the St. Pancras (Middlesex) Electric Lighting Order 188x (the last number was not readable, but I believe to be 1888).

Loans were raised to fund the construction including an initial £70,000 loan, a temporary bank loan of £21,269 then in 1891 a loan of £10,000 from the London County Council.

Land was purchased for a total of £10,827, which included a number of houses along Longford Street which then contributed rent into the accounts of the power station.

Initial site clearance and erection of a hoarding was done by George Tatum for £36. Additional hoarding was provided by F.H. Culverhouse & Co. for £4, 17s, 6d.

Machinery and plant cost £24,878 and the laying of mains cables and services including royalties (presumably to land owners) came to £33,787.

The initial batch of public lamps cost £6,723 and £3 was spent on posters and £40 on advertising.

The station started generating electricity in 1891. The following table shows how the number of consumers, electricity generated, lamps and motors grew in the first few months of operation.

| 30th Nov 1891 | 31st Dec 1891 | 31st Jan 1892 | 28th Feb 1892 | 31st Mar 1892 | 30th April 1892 | 31st May 1892 | 30th June 1892 | ||

| Number of Consumers | 57 | 72 | 81 | 93 | 103 | 108 | 115 | 119 | |

| Daily Consumption (Units) | Minumum | 17 | 33 | 79 | 174 | 104 | 201 | 187 | 144 |

| Maximum | 390 | 1825 | 3105 | 1641 | 880 | 1248 | 842 | 861 | |

| Average | 220 | 665 | 1145 | 1067 | 640 | 757 | 625 | 540 | |

| Number of Arc Lamps | 68 | 71 | 68 | 67 | 83 | 83 | 85 | 85 | |

| Number of Motors | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | |

The annual accounts provide very detailed information on the performance of the power station. Two examples of the information recorded are shown below.

For the month of January 1893:

| 260 tons of coal delivered at a cost of £260 |

| Station staff: 18 |

| Outdoor staff: 11 |

| Total units sold: 49,750 |

| Customers: 167 |

| Units to private houses: 3,973 |

| Units to other than private houses: 43,775 |

| Public Lighting: 20,211 |

| Complaints as to supply to Consumers and Arc Lights: 6 |

and for the month of December 1893:

| 306 tons of coal delivered at a cost of £272 |

| Station staff: 19 |

| Outdoor staff: 24 |

| Total units sold: 57,784 |

| Customers: 238 |

| Units to private houses: 5,119 |

| Units to other than private houses: 49,268 |

| Public Lighting: 27,252 |

| Complaints as to supply to Consumers and Arc Lights: 5 |

| 589,690 Gallons of water used = 5.4 gallons per unit generated |

| 672,000 lbs of Coal used = 6.1 lbs per unit generated |

Interesting that whilst the Station Staff stayed almost static, the number of Outdoor Staff more than doubled. I assume this was due to the manpower required to connect a growing number of new customers to the supply system across an infrastructure that did not yet exist and to maintain the connections of existing customers.

The volume of coal and water needed to support generation gives some idea of the complex infrastructure and supply chain required to continue round the clock operation.

Also note that at this early stage, utilities were recording the number of complaints, something that utilities would continue to do well over 100 years later.

The accounts also record the average number of units consumed per household. These are shown in the following table and show a considerable increase per household during the last decade of the 19th century. Presumably due to the increased use of electric lighting and new electrical appliances being developed and bought by householders:

| 1892 | 18.8 | 1896 | 47.7 |

| 1893 | 24.7 | 1897 | 63.12 |

| 1894 | 29.57 | 1898 | 82.91 |

| 1895 | 35.29 | 1899 | 102.86 |

The generation of electricity allowed the transition to start from gas to electric street lighting and the Vestry of St. Pancras were one of the first municipal authorities to start this change.

The Engineer article and the accounts refer to some of the drivers for moving to electric street lighting and also some of the other day to day events for the power station and Vestry:

– In consequence of the War in South Africa, great difficulty in obtaining supplies of smokeless steam coal. As a result, the price of smokeless coal has increased between 50% and 75% on previous years contracts;

– Numerous complaints have been received of smoke nuisance;

– Four workmen employed by the department who were reservists and have been called up. Their wives are receiving half pay;

– For the gas street lights still in use in 1897, the wages of the lamp lighters increased from 21s 6d to 24s per week.

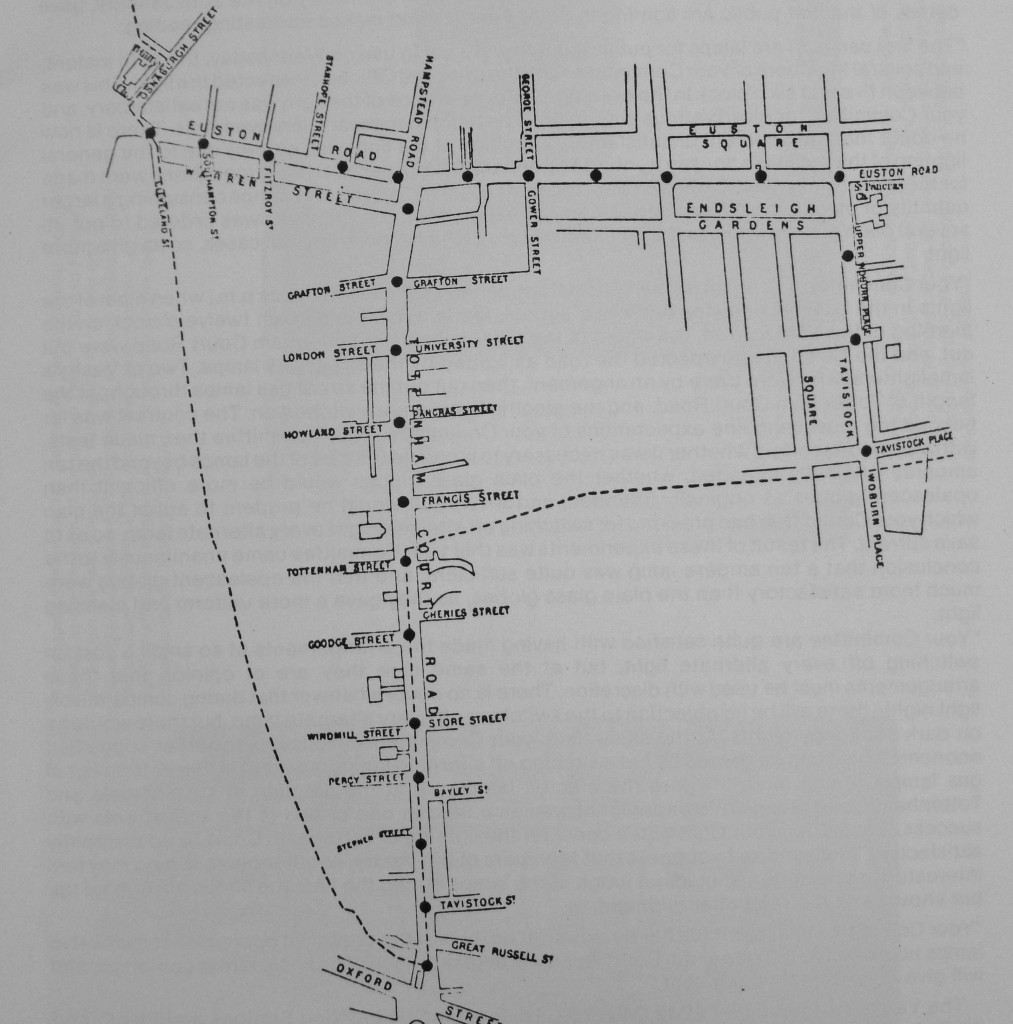

Tottenham Court Road and Euston Road were some of the first streets to be lit using electricity from the Regent’s Park Central Station. A number of experiments were undertaken to identify the best position for street lamps, their height and the type of light generated by arc lamps.

The best position for lamps was identified as being in the centre of the road and close to side roads. This enabled an even spread of light across the road, with light penetrating down side roads. Lights were installed and connected to the supply from the Regent’s Park station and in January 1892, Tottenham Court Road became the first street to be lit by electric lamps and electricity supplied by the Vestry of St. Pancras. A committee from the Vestry visited Tottenham Court Road and were most satisfied by the lighting from the new street lamps, which provided twelve times more light than the gas lamps they replaced.

The following map shows the position of the new arc lamps installed by the Vestry of St. Pancras.

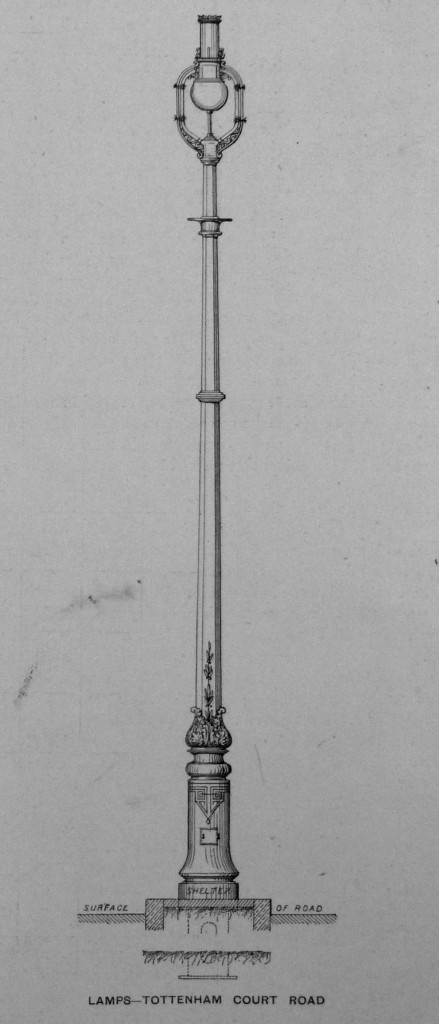

The original design of the street lamps.

These original street lamps are still in place, although converted to modern forms of lighting and electricity (the original power station produced Direct Current unlike the Alternating Current (AC) of today’s electrical system). Just before visiting Longford and Stanhope Street I walked along part of Tottenham Court Road to take a look. The streetlamp at the junction with University Street and Maple Street.

Looking up Tottenham Court Road to the junction with Euston Road. The final two street lamps at the top of Tottenham Court Road which also appear to have lost their glass domes.

The St. Pancras Vestry was the first municipal authority in London to generate electricity. Others swiftly followed. Hampstead Vestry in 1894 and Islington in 1896. Shoreditch implemented an innovative way of generating electricity and profit for rate payers by using their refuse destructor as a means of generating electricity and disposing of waste.

By the end of the 19th century there were some 200 miles of streets across London lit by electricity generated by municipal authorities.

Victorian London is often portrayed through the perspective of fog and Jack the Ripper. I much prefer the view of an innovative city with a growing infrastructure and the sophistication and organisation to start the delivery of services that today we take for granted.

I hope that one day I will find some photos of the Regent’s Park Central Station, however it was still a moving experience to stand in Longford Street early one January morning and look at the site where my grandfather worked many years ago.