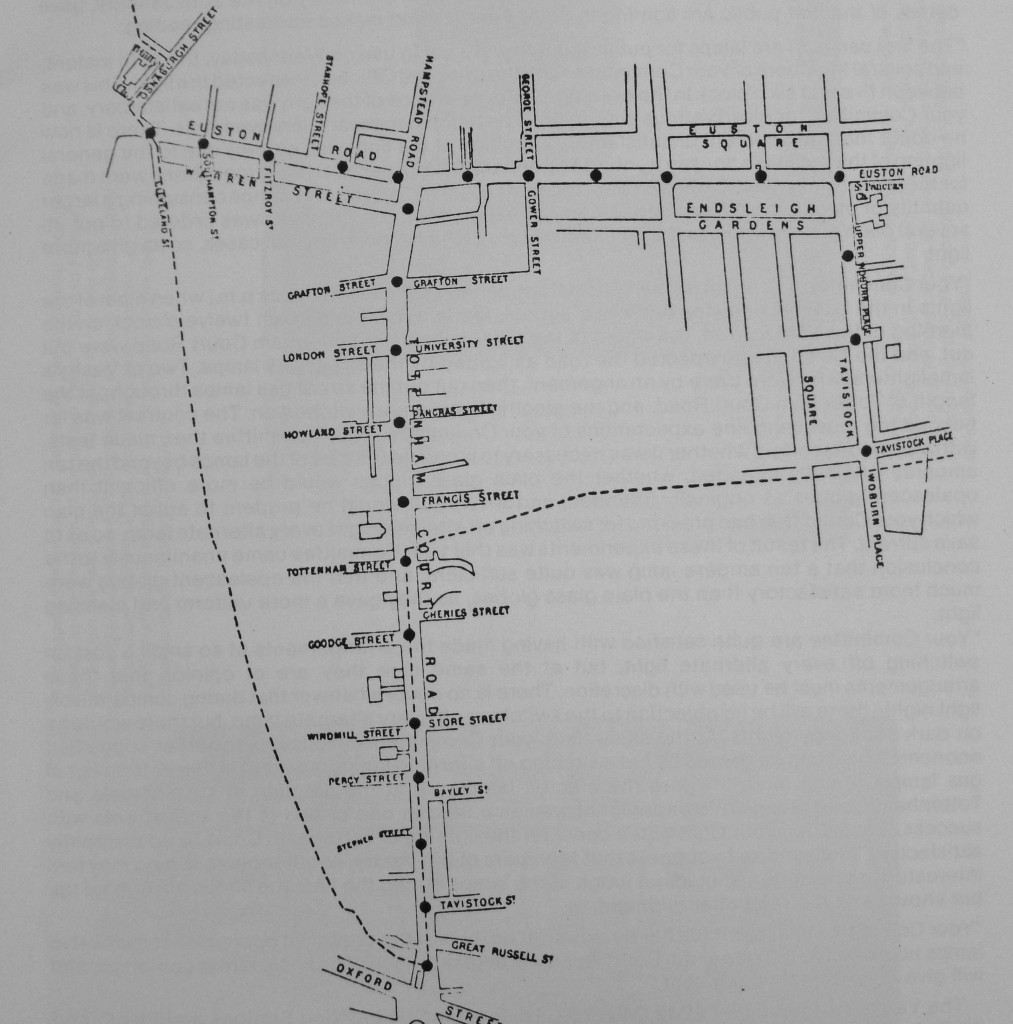

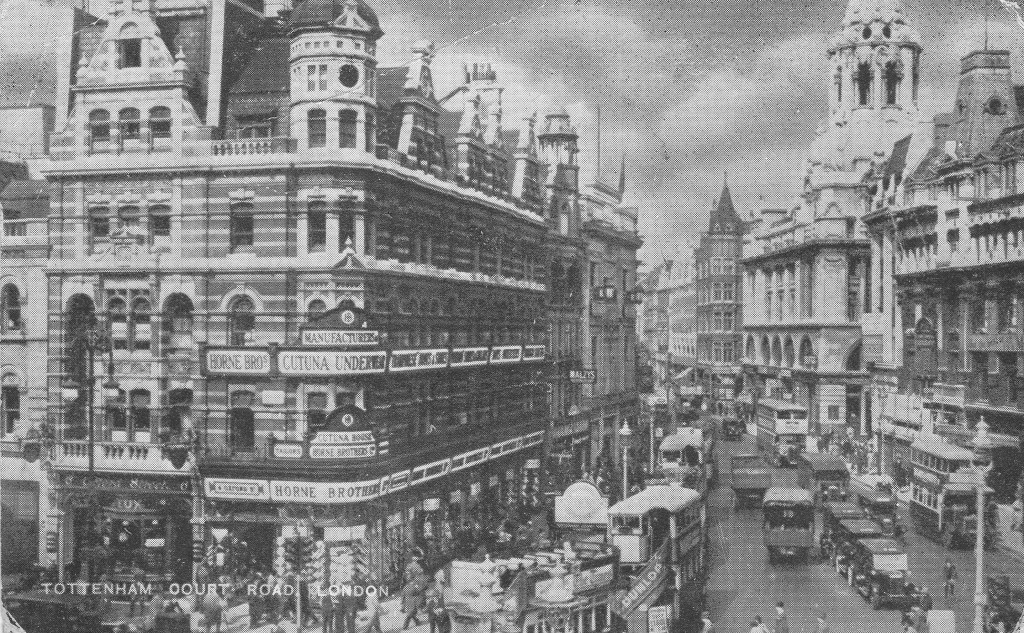

Warren Street is probably better known by the underground station of the same name, at the junction of Tottenham Court Road and Euston Road.

Warren Street runs parallel to Euston Road between Tottenham Court Road and Cleveland Street and my reason for being in Warren Street was to track down the location of one of my father’s 1980s corner shop photographs.

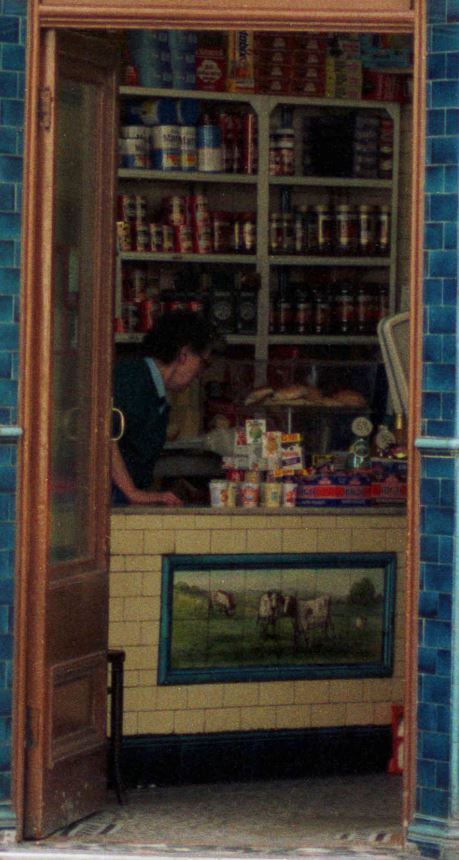

This is the corner shop of J. Evans, Dairy Farmer on the corner of Warren Street and Conway Street, photographed in 1986.

The same location, 33 years later in 2019, now occupied by The Old Dairy coffee shop.

The shop front and the railings are Grade II listed. The listing states that the building was constructed around 1793 with the shop front dating from 1916. I suspect that J. Evans was one of the Welsh dairy farmers who set up shop in London. The inside of these corner shops are very similar, shelves packed high with tinned and packet goods.

An enlargement of the view through the door shows a wonderful tiled picture of a field and cows, part of a set of scales can be seen to the right and the shop assistant is behind the counter.

This was only 33 years ago, but this type of local shopping is now dominated by the big supermarket brands, and a small store like this could probably not afford the rent or business rates.

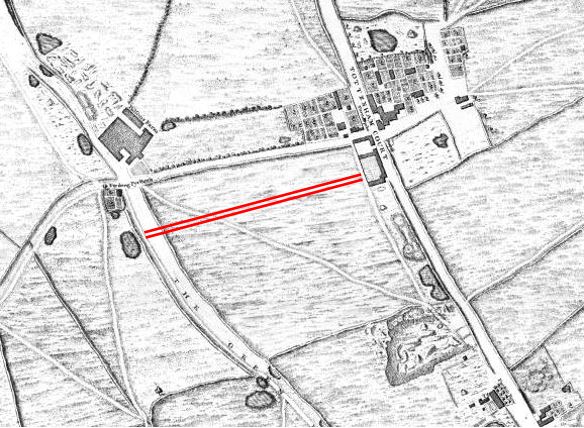

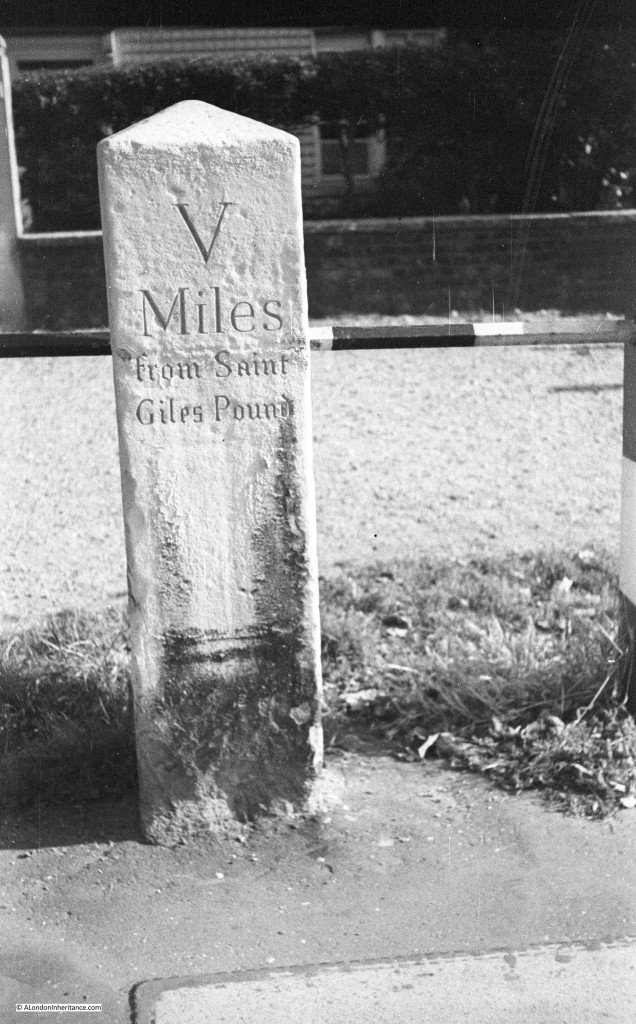

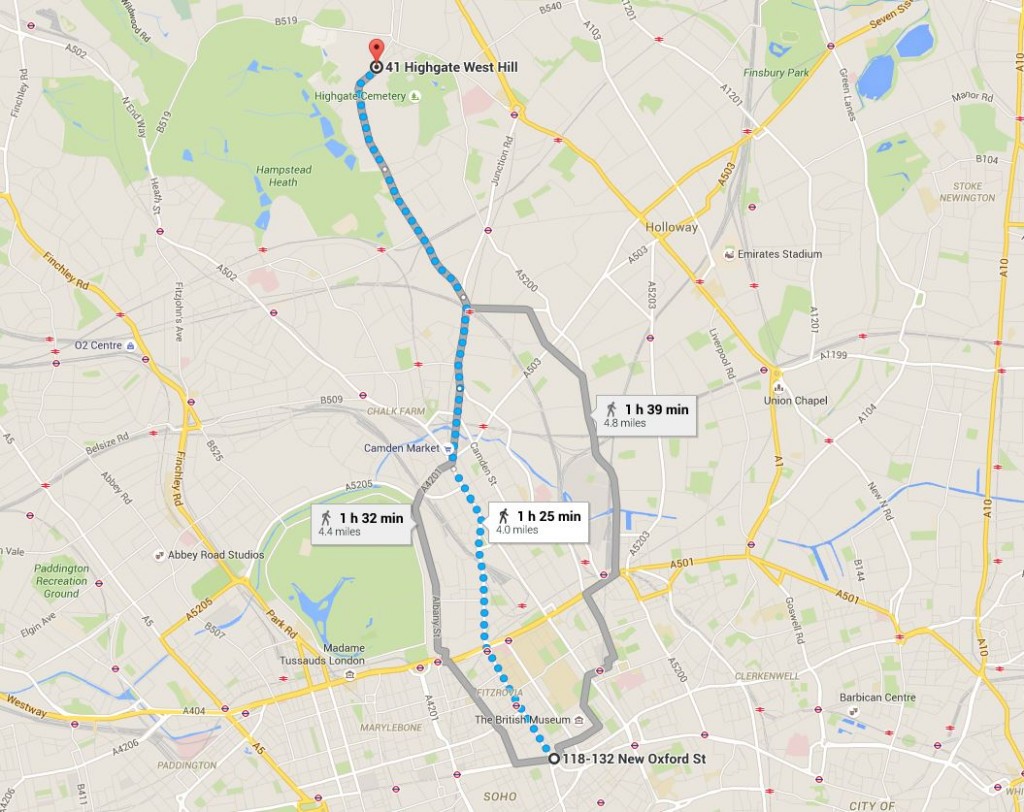

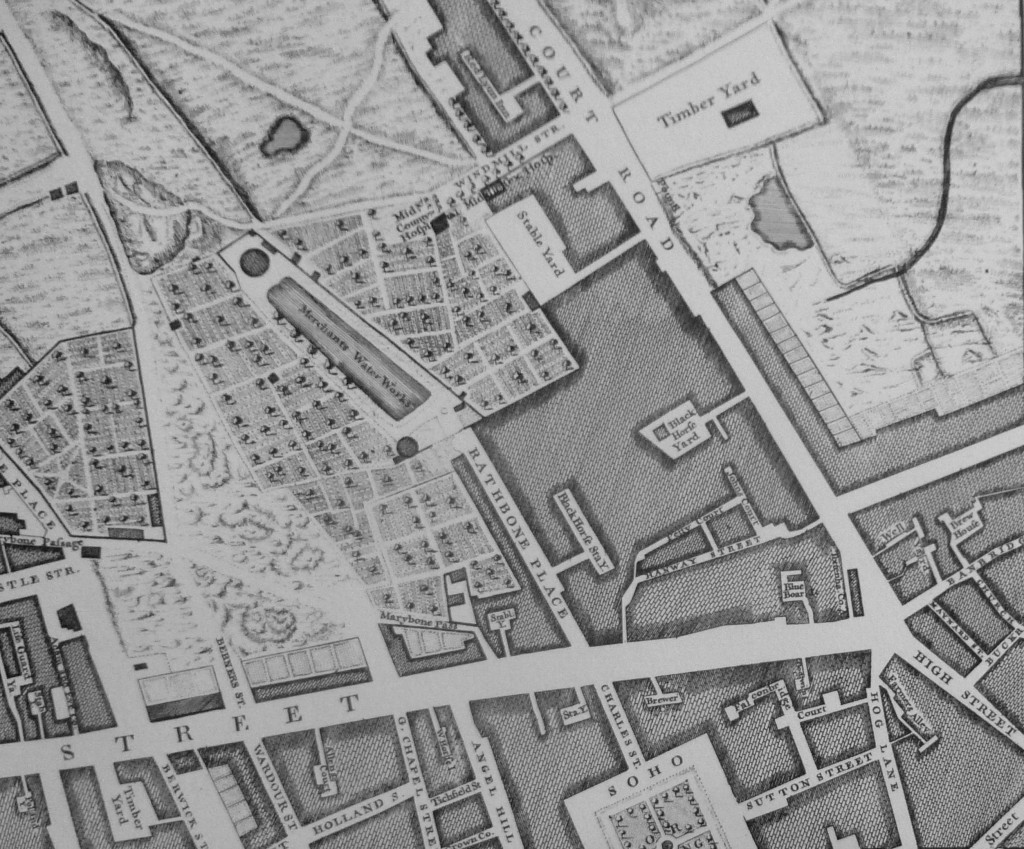

The tiled picture of fields and cows could have been the scene where Warren Street is located back in 1746. At the time when John Rocque complied his map of London, the city had not yet reached as far as Warren Street and the area was still mainly fields, with some limited building just north of the future junction of Tottenham Court Road and Euston Road. In the following extract from Rocque’s map, Tottenham Court Road is on the right. I have marked the approximate location of Warren Street with red lines, running across the full width of a field.

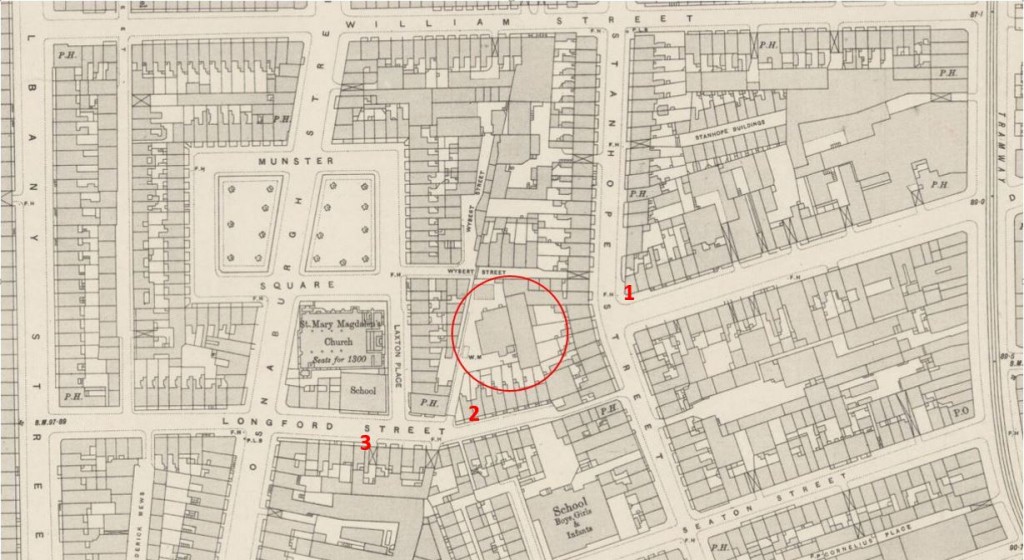

One hundred years later, and all the fields of Rocque’s map would be buried under a significant northward expansion of the city. The following map extract from Reynolds’s 1847 map (now I have the map out the shoe-box for last week’s post, I will use it more) shows Warren Street just above the centre of the map, with building covering the entire area (apart from the corner of Regent’s Park shown top left).

Warren Street was built between 1790 and 1791. The street is named after the daughter of Sir Peter Warren, Anne Warren the wife of Charles Fitzroy, the 1st Baron Southampton who was the owner and developer of the land on which Warren Street was built.

Warren Street is relatively quiet, a mix of architecture, but retaining many original buildings.

The street runs parallel and a short distance to the south of the busy Euston Road. Standing in Conway Street and looking across Warren Street, Euston Road can be seen, along with the new office buildings of the Regent’s Place development.

Looking south down Conway Street from Warren Street and a mainly original street plan and buildings survive.

In the above photo, the J. Evans corner shop can be seen on the right. Note the lighter bricks on the second and third floors. The difference in bricks is due to a mid 20th century re-build of the top two floors.

The London Metropolitan Archive, Collage site has a couple of photos of J. Evans shop. The following photo dates from 1978.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_337_78_689.

A couple of large adverts are on the Warren Street facing wall. Also note that just along Warren Street were some other shops. Difficult to see exactly what they are selling, but they look to be typical of the shops serving the day to day needs of local residents that were once found all across London. Today, these shops have been converted to a couple of private clinics.

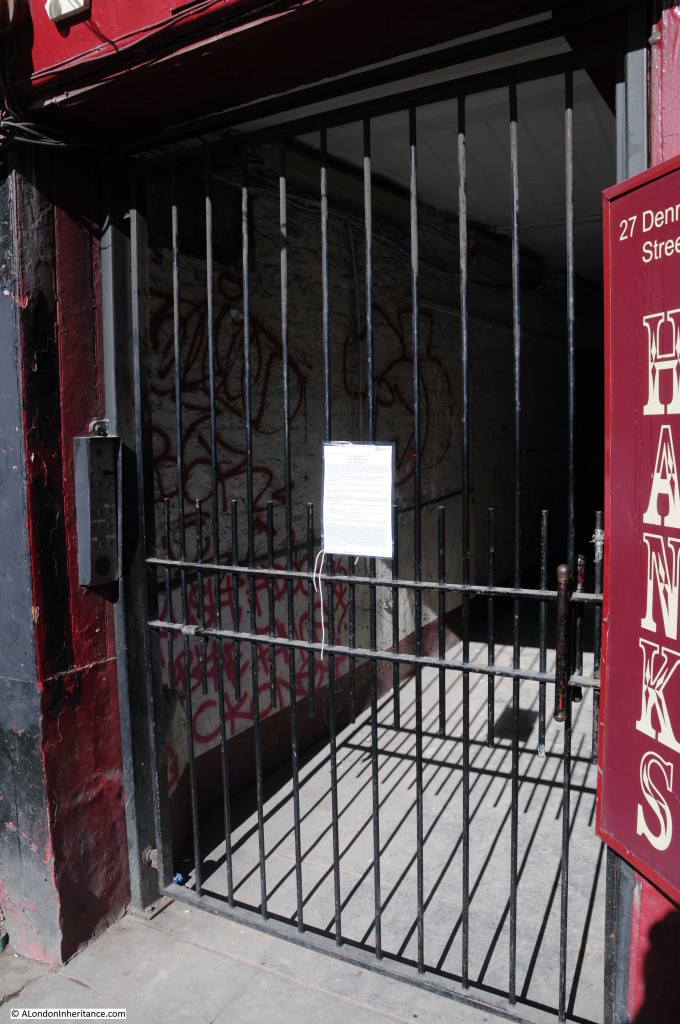

The buildings in which these other shops were located have what appears to be a secret entrance to a different place – this is the entrance to Warren Mews.

Warren Mews is a short street, even quieter than Warren Street, although I dread to think how much the houses that line the mews cost.

After having found the old shop frount, I walked back down Warren Street towards Tottenham Court Road, viewing an interesting series of buildings as I walked.

The Smugglers Tavern:

I do get depressed when walking the streets of London looking at the loss of one off shops, specialist shops and businesses, however in Warren Street I found a survivor. This is the London premises of Tiranti – a UK manufacturer and supplier of Sculptors equipment.

The business was founded in High Holborn by Giovanni Tiranti in 1895. The business relocated to a number of different locations over the years, and whilst the main business is now located in Thatcham, Berkshire, Tiranti still retain a London premises.

The shop window of Tiranti in Warren Street:

Tiranti has a fascinating history. Their web site can be found here, and contains an “About” page with a history of the business and their moves across London.

Although Tiranti has survived, another specialist business in Warren Street recently closed.

At the junction of Warren Street and Fitzroy Street is a large corner store, currently occupied by the Loft furniture business as their London showroom.

Until early 2017, this was the building occupied by French’s Theatre Bookshop:

The French’s business was established in London around 1830. The bookshop occupied several locations across London and moved to the Warren Street / Fitzroy Street location in 1983, so whilst not a long term occupier of the site, it was good to find a specialist business serving the acting community of London and further afield.

After closure, French’s went fully online, but has now reopened a bookshop at the Royal Court Theatre.

A few years ago I photographed the original entrance sign for Samuel French. It is remarkable how quickly places change.

The LMA Collage site identifies the same corner shop, now occupied by Loft, previously by French’s Theatre Bookshop, was in 1972 occupied by a second-hand car business.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_340_72_1023.

Used car dealing was a specialty of Warren Street for much of the first half of the 20th century with car dealers occupying many of the buildings and also second-hand cars for sale lining the street. The business on the corner with Fitzroy Street must have been one of the last in operation on the street.

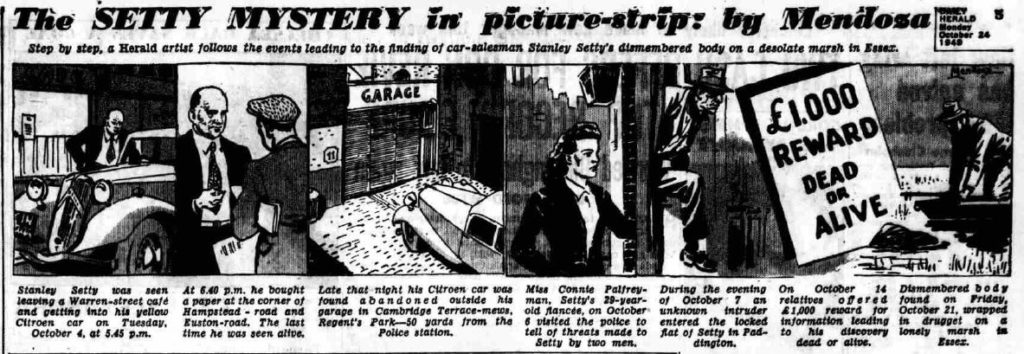

The car dealing business in Warren Street attracted a number of dubious characters, one of whom was Stanley Setty, a car dealer who operated outside a cafe on the corner of Warren Street and Fitzroy Street (on the opposite side to the above photo) . Setty dealt in cash only and was always in possession of large amounts of cash.

He had an associate in Brian Donald Hume who dealt in black market goods. In 1949, after an argument and a fight, Setty was murdered by Hume, who disposed of his body parts over the Essex Coast from a hired plane.

The Daily Herald on the 24th October 1949 included a graphical report of the murder (©British Newspaper Archive)

Hume was found not guilty of the murder, only the lesser offence of being an accessory to the murder by disposing of the body. After his release from prison he was happy to report to the press that he had carried out the murder – the defence of double-jeopardy protecting him from a new trial.

Warren Street is a very different street today.

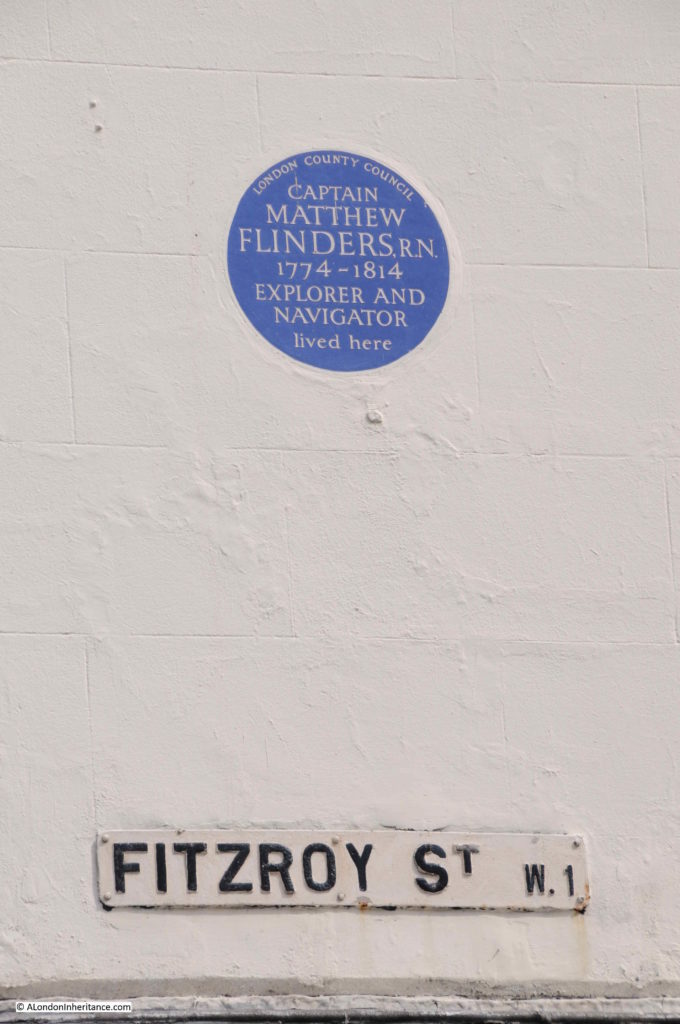

On the Fitzroy Street side of the Loft / French’s Theatre Bookshop building is a blue plaque which has an interesting connection to recent excavations.

Captain Matthew Flinders was instrumental in identifying Australia as a continent, by being the first western explorer to circumnavigate the land, which he would also play a part in naming.

His name was all over the media earlier this year when his grave was discovered during the excavations of St James’s burial ground as part of the HS2 extension to Euston Station, a short distance along the Euston Road from Warren Street.

Captain Matthew Flinders (source here).

Warren Street has some interesting shop fronts:

Original terrace of houses, shops on the ground floor, offices and / or flats above. Work on the buildings over the years shown by the different brick colours.

At the junction of Warren Street and Tottenham Court Road is the underground station that bears the street’s name.

The first underground station opened here in 1907, with the current building dating from 1934.

The station is on the Northern and Victoria lines, and is a very busy station during week days.

Large numbers of people use the station for the offices at Regent’s Place, University College Hospital, University College London, and the businesses that line Tottenham Court Road and the surrounding streets. It is a station I have used many times and during the early morning peak hours the automatic ticket gates are usually left open to speed passengers through from the escalators to the street.

Since being a field on the northern edge of John Rocque’s London, Warren Street has been home to some lovely late 18th century buildings, the discoverer of Australia as a continent, the arrival of the underground, used car dealers, and J. Evans – Dairy Farmer, the shop that was the reason for my walk along Warren Street.