The church of St Bride’s is set back from Fleet Street, and the body of the church is not that visible, however walk a short distance and the steeple of the church rises above the surrounding buildings:

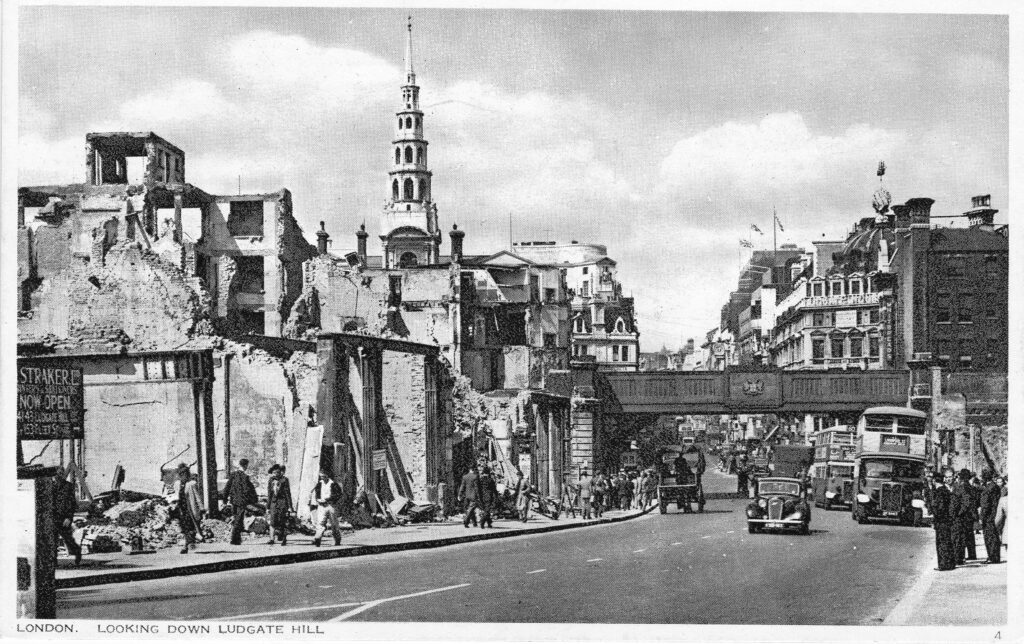

Remarkably there has not been any taller buildings in the surrounding streets which could obscure the view of the steeple, and the roof line of Fleet Street is much the same as it was in the 1940s when the following view for the postcard series “London under Fire” was taken:

A visit to St Bride’s today, reveals two distinct sides to the church. There is the historic church, which includes evidence of the Roman city almost 2,000 years ago, and there is the church today which is the spiritual centre for a profession that we see on our TV screens every day.

The design of the current church dates from Wren’s post Great Fire rebuild of the church. The previous church having been completely destroyed by the fire that devastated so many City churches,

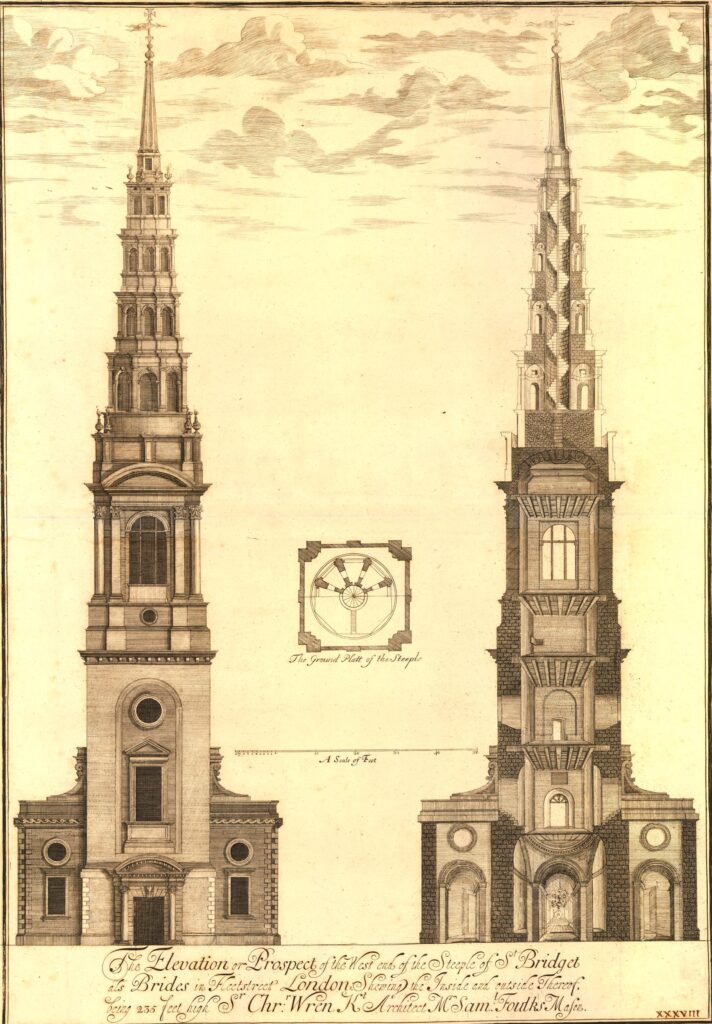

Although the rebuilt church reopened in 1675, the steeple was not completed until 1703. The steeple was Wren’s tallest steeple and today is actually 8 feet shorter than when originally completed due to a lightning strike and subsequent rebuilding work.

The steeple is also traditionally thought to be the inspiration of the tiered wedding cake, and up close, the steeple provides no reason to doubt this story:

The following drawing, dated 1680, shows the steeple of the church, and confirms that the steeple today is identical to Wren’s original design. The drawing on the right shows some very tempting stairs running up the middle of the steeple (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

St Bride’s today is completely surrounded by buildings so apart from the steeple it is really difficult to appreciate the overall design of the church. The following print shows the church open to the west (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The above print is dated 1753, however Rocque’s map of London seven years earlier shows the area in front of the church occupied by buildings, so I do not know if some artistic licence was used in the above print, or whether the block had been demolished, and the artist had used the opportunity to portray this unique view of St Bride’s.

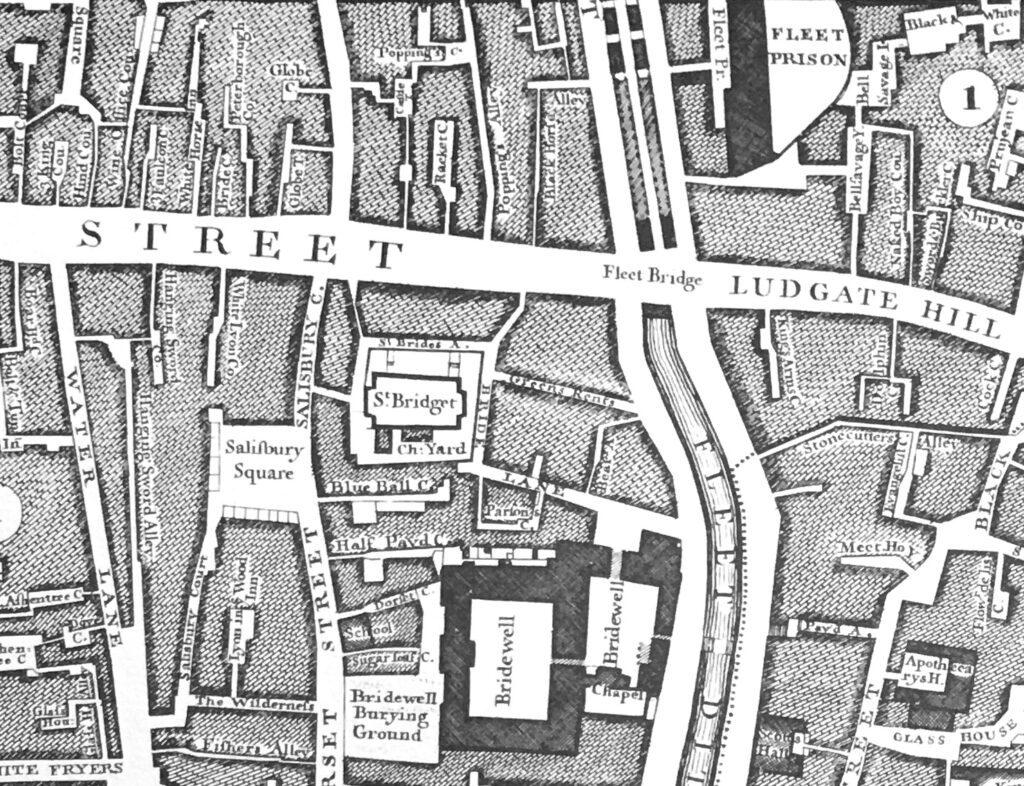

In the following extract from Rocque’s 1746 map, St Bride’s (marked as St Bridget) is shown just to the left of centre, and as now, was surrounded by buildings.

St Brigit (St Bride) was an abbess of a number of convents in Ireland, the most important of which was at Kildare. Brigit is believed to have lived between 451 and 525, and there are very few, if any, written records from that time, with what is known of her coming from later writings and anecdotes.

The majority of churches dedicated to St Brigit / Bride, or place names, are in Ireland or Wales and the west of England (such as St Brides Bay in Wales). The church in London is a rare example of the name in the east of the country.

Looking at the extract from Rocque’s map, and to the north of the church is “St Bride’s A”. This is St Bride’s Avenue, a narrow passageway that still runs between the church and the buildings on the southern side of Fleet Street:

In the above photo, a gate between the two lights leads into the churchyard, and a side entrance into the church, however I much prefer the entrance underneath the tower, as this entrance provides a view from under the tower into the brightly lit nave of St Bride’s:

St Bride’s was devastated during the last war, when bombing and fire, mainly during December 1940, reduced the church to a shell of side walls, tower and steeple.

The interior we see today is to Wren’s core design, but is the result of the post war rebuild, with everything, including floor, all wooden structures, roof etc. being from the 1950s and later refurbishments:

The view from close to the altar, looking back along the church to the entrance under the tower:

I have touched on the history of the church, but there is far more to discover which I will come to later in the post, however whilst in the church, there is the opportunity to explore one aspect of St Bride’s that is very relevant to life today.

St Bride’s has a long association with the print trade and journalism, dating back to around 1500 when the printing press of Wynkyn de Worde was established near the church. This association grew with the rise of Fleet Street as a centre of journalism and the newspaper industry.

Whilst newspapers have left Fleet Street, St Bride’s maintains this connection.

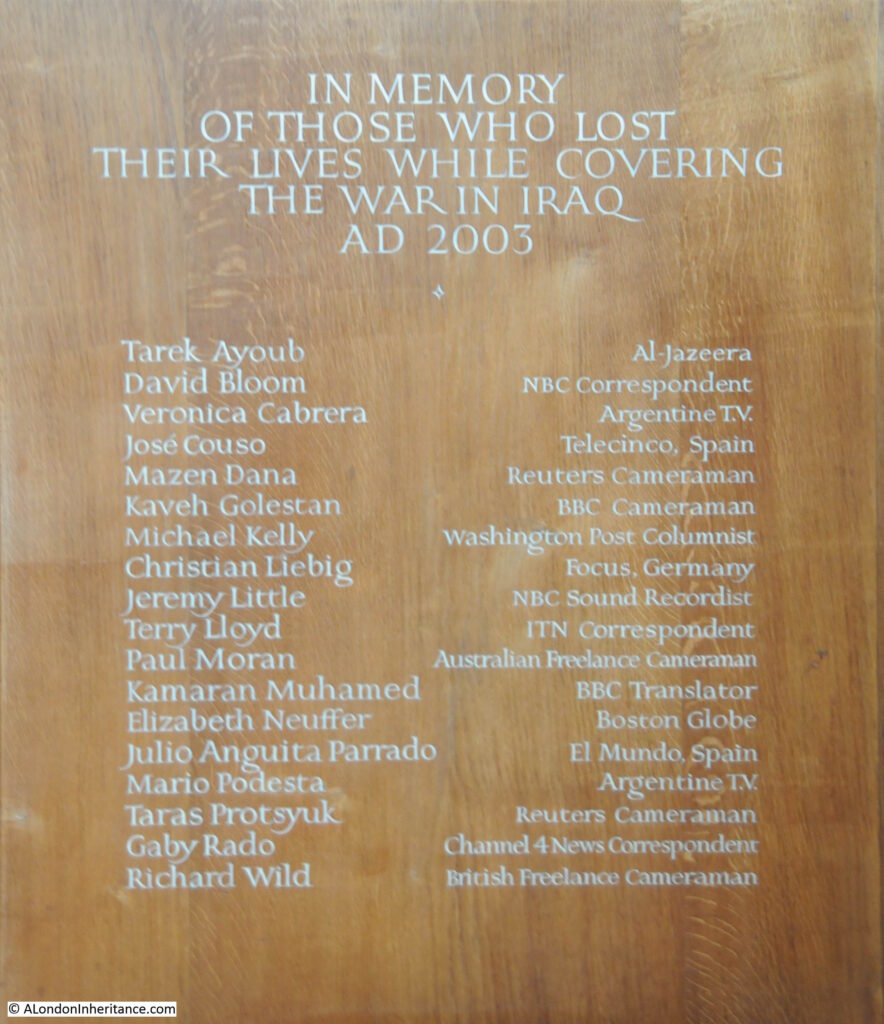

If you watch TV news today, or listen to a radio report, chances are these will be from a journalist and their support staff in Ukraine. Kitted out in protective gear. Those who report from war zones run a very real risk of injury or death, and those who have been lost in previous wars are commemorated in St Bride’s, including this memorial to those who lost their lives whilst covering the 2003 Iraq war:

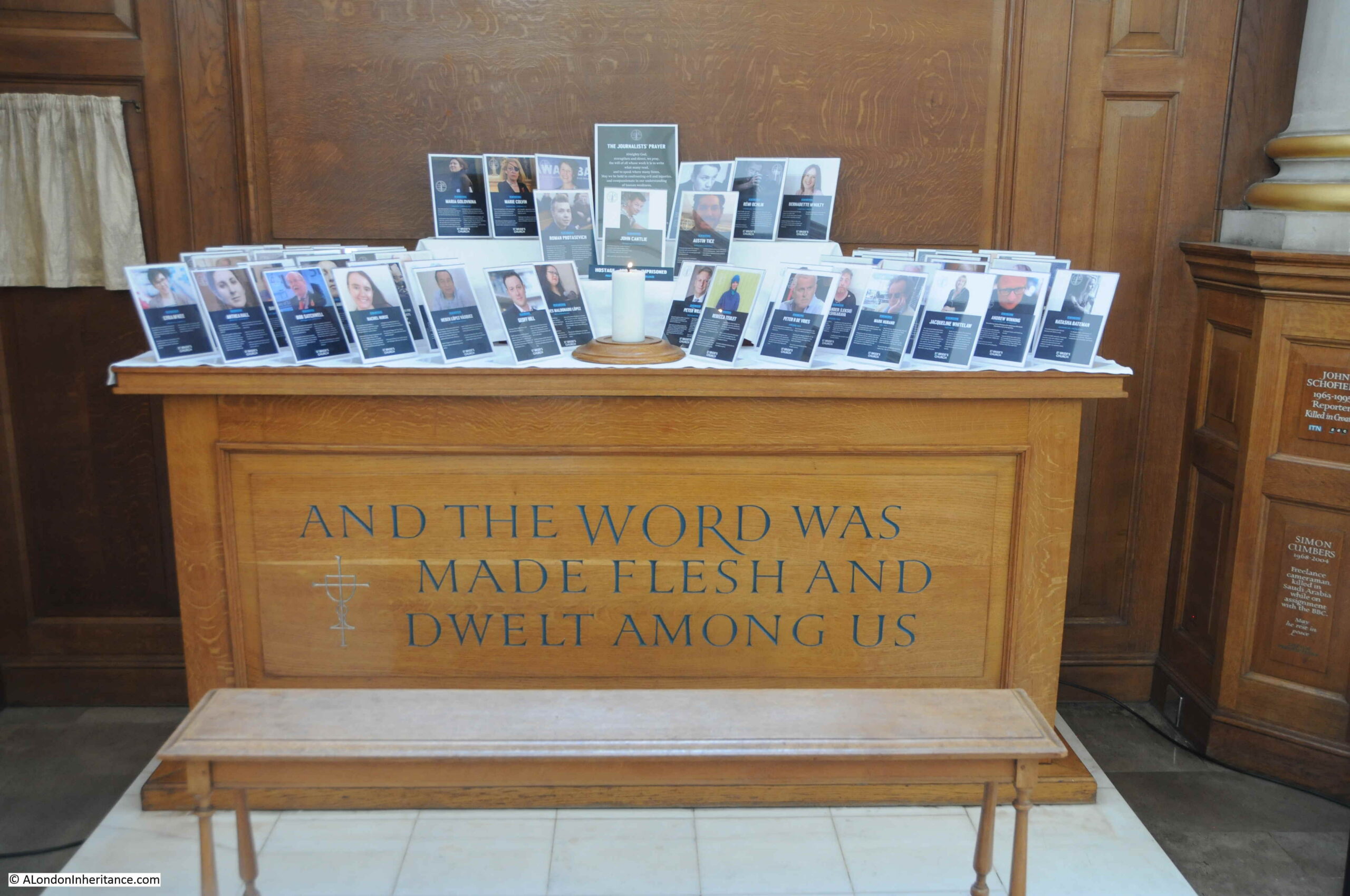

St Bride’s has also created a Journalists’ Altar, to commemorate those within the profession who have died, are held hostage or have an unknown fate.

Unfortunately, there are too many to display at any one time, so the photos are rotated.

The three photos just above the candle are for Roman Protasevich, the Belarusian journalist who was arrested at Minsk airport in 2021. In the centre is John Cantile, who was taken hostage in Syria in 2012 by Islamic State and is still missing, and on the right is American freelance journalist Austin Tice who was also kidnapped in 2012, in Syria.

On either side of the Nave of the church, there is wooden seating, and these seats also have plaques commemorating those in the profession who have died. I have selected two to show the range of those named in St Bride’s.

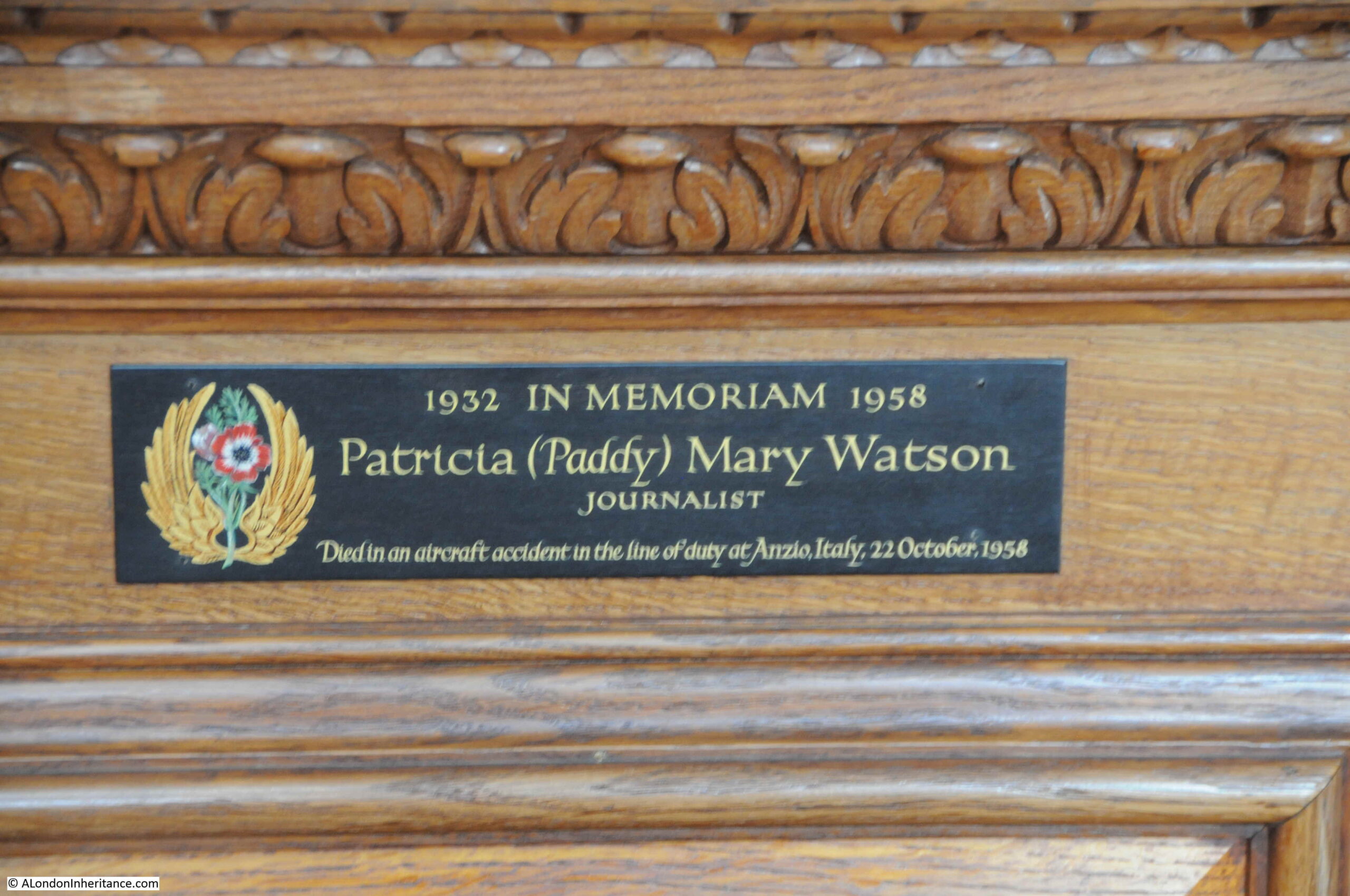

The first is Patricia (Paddy) Mary Watson:

Patricia Watson was a journalist on the staff of the Daily Sketch, who died at the age of 23 in an aircraft accident over Italy on the 22nd of October 1958.

I found the details of the accident recorded in newspaper reports from the time, as follows:

“A British European Airways Viscount and an Italian Air Force jet fighter collided near Nettuno, central Italy, and the airliner plunged to earth with the feared loss of 30 lives, cables Reuter.

Airport authorities in Rome said it was believed none of the 25 passengers and five crew survived. The fighter pilot was reported to have parachuted into the sea and was then picked up by a rescue launch.

BEA’s manager in Rome, Mr. David Craig, said he had been informed by the Italian authorities that all on board the Viscount were dead. The airliner was flying from London to Malta via Naples.

The Viscount and the fighter, an F36 Sabre jet, collided between Nettuno and Anzio. The wreckage of the Viscount was ten miles south-east of Anzio, a short distance inland from the sea, Mr. Craig said.

A police official at Nettuno said that after the collision, there was a terrific explosion. The British airliner blew up. Everyone on board must have been killed instantly. the wreckage came streaming down in a shower. The biggest piece was not more than a yard long.

The pilot of the fighter managed to parachute out of his plane immediately and the plane went on flying for a short distance before plunging downwards. The pilot of the fighter, Capt. Giovanni Savorelli, was taken to Nettuno hospital suffering from shock, Hospital authorities said he was otherwise uninjured.

An Italian civilian is believed to have been killed on the ground by falling wreckage. Within two hours of the crash Italian police announced that 15 bodies had been found. Police said the airliner was flying at 23,000 ft. at the time of the collision.

Among the dead were Miss Patricia Watson (23), a member of the Daily Sketch staff. Mr. Brian Fogaty (25) freelance photographer, and Mr. Lee Benson, free-lance reporter. They were on a Daily Sketch assignment.

Another member of the party was Miss Jane Buckingham (22) a London model.“

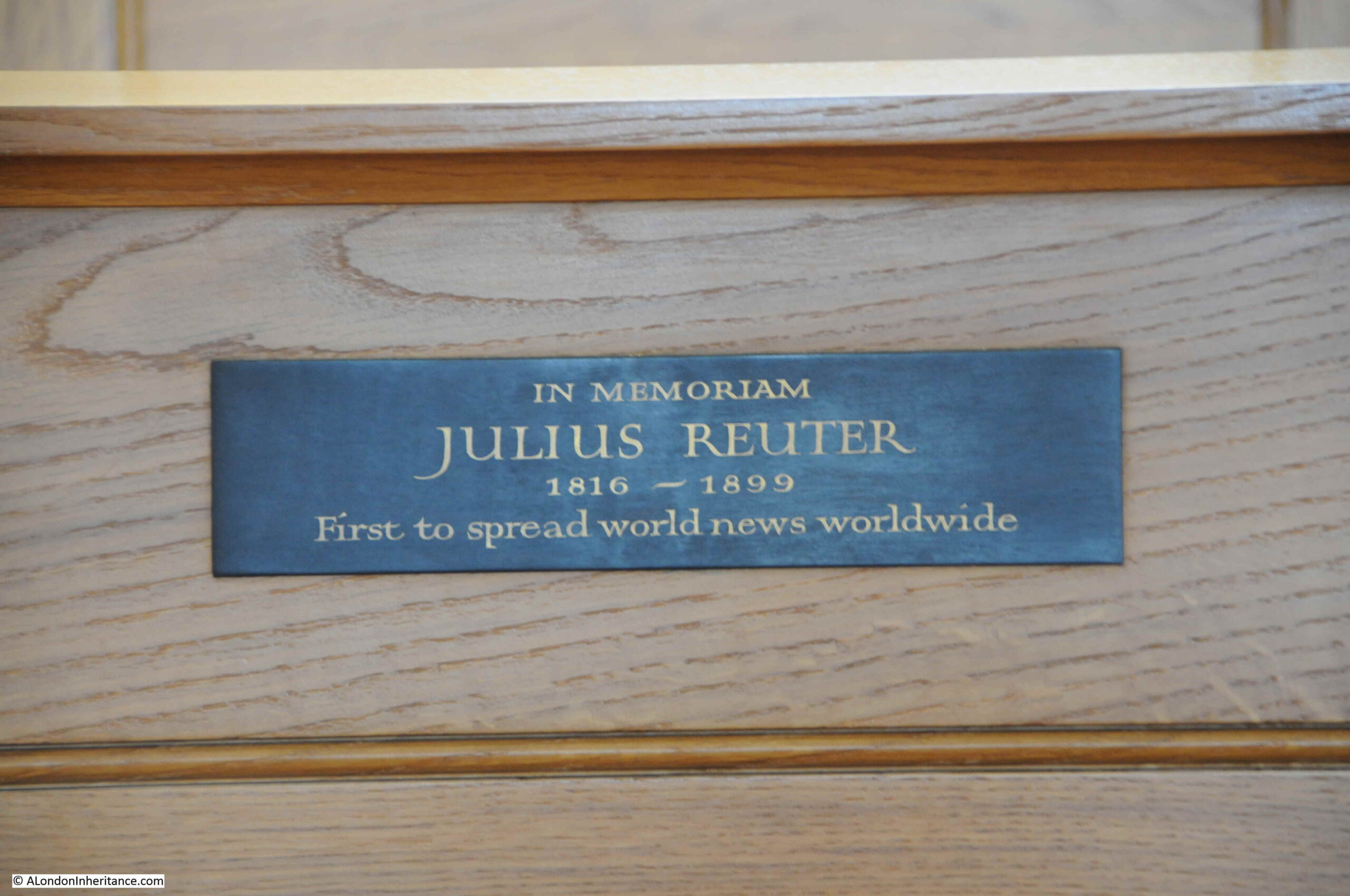

The first paragraph of the above report mentions Reuter as the source of the news, which brings us to the second plaque, to Julius Reuter:

Paul Julius Reuter was a German immigrant to London. In Germany he had been running an early form of financial news service which relied on the telegraph and even carrier pigeons, to distribute financial information such as the prices of stocks.

In 1851, he set-up an office in the City of London, and using a new telegraph cable between London and Paris, started transmitting stock market quotations and news between the two city’s.

Reuter established the company known as Reuters, and as submarine cables and radio services allowed global communication, Reuters built a global network of journalists providing news and financial information, so as the plaque states, he was “First to spread world news worldwide”.

Reuters struggled somewhat in the early years of the 21st century, and in 2008, Reuters merged with the Canadian media organisation Thompson, to form Thomson Reuters.

Reuters had a presence close to St Bride’s, with offices at 85 Fleet Street, in the building designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, and completed in 1938 for the Press Association.

St Bride’s relationship with the professions of print and journalism are very much alive today, however I hope that no more names need to be added to those who have died whilst working as journalists.

I have touched on the history of the Wren church we see today, and there is a much older side to the church, which we can see with a visit to the superb displays in the Crypt:

To discover the history of the Crypt, I turned to my go to book for post-war archeological excavations across the City – “The Excavation of Roman and Mediaeval London” by W.F. Grimes.

St Bride’s had a Mediaeval crypt, which had been retained when Wren rebuilt the church in the 17th century, however access to the crypt had been lost, and apart from a drawing preserved by the Reverend John Pridden who was a curate at St Bride’s from 1783 to 1803, there was no information on the layout of the crypt.

In the section on St Bride’s, Grimes explains that the church authorities invited the Roman and Mediaeval London Excavation Council to look for the vault before work started to rebuild the church.

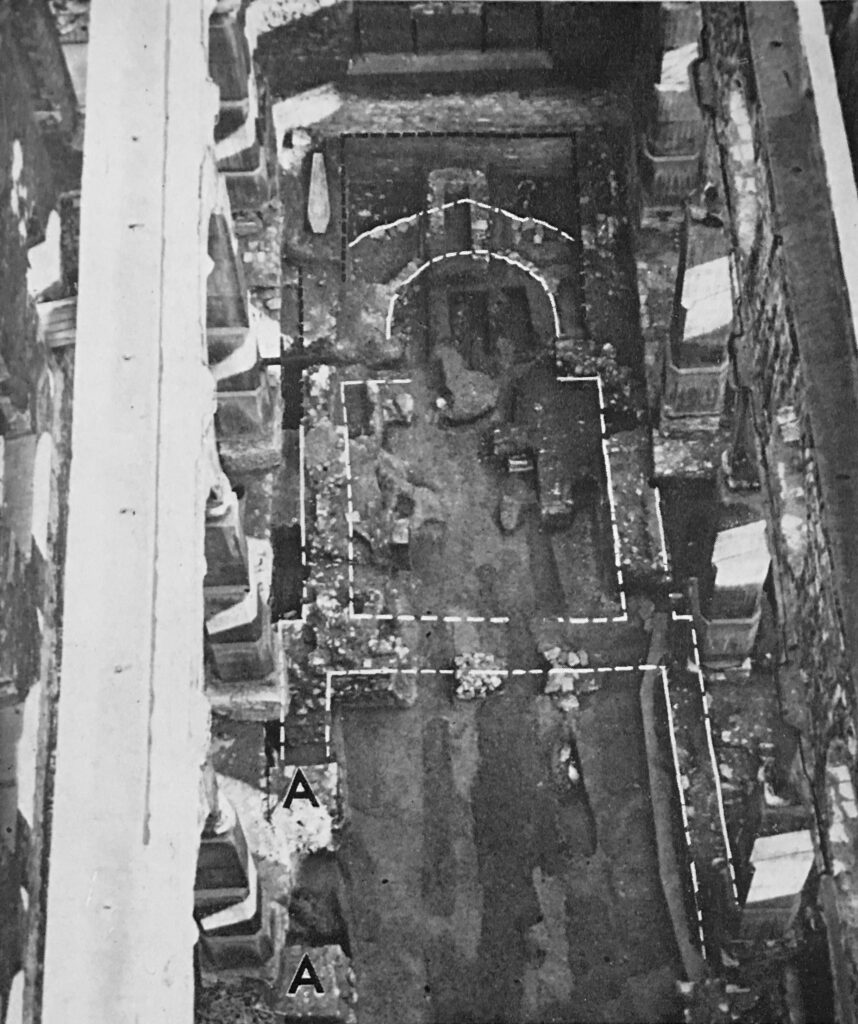

The invitation was accepted, along with a request to extend the excavation beyond just the discovery of the crypt. The post-war state of the church can be understood with the following photo from Grimes book, showing the interior of the church from above:

The white outline in the photo is that of the early Anglo-Norman church.

Walking down to the Crypt today, and there are two sections. On the left is a narrow walkway, where we can walk alongside the remains of some of the early walls and foundations of the church:

This section of the crypt has a number of memorials from the pre-war church, alongside more memorials to those in the media:

On the right is the main section of the crypt, where the key features found during the post war excavation can be seen along with display cases telling the history of the church, and displaying some of the finds from the excavations.

Grimes explains that the history of the site begins in the Roman period, when a stone building with a plain floor of red and some yellow tesserae was found at the eastern end of the church, some 10 feet below the floor level of Wren’s church.

The floor sections discovered are behind walls and foundations of medieval versions of the church, and can be seen today via mirrors which reflect the view of the Roman floor from behind the stone walls:

The Roman floor was found to have been built on natural gravels, which extended westwards within the church, gradually increasing in height.

The level of the Roman floor is very similar to that of the streets that surround St Bride’s church today, which as shown in the earlier view of St Bride’s Avenue, are lower than the church, and descend to the east.

Another part of the Roman floor on display:

As well as the Roman tiled floor, an unexpected feature found towards the western end of the church was a Roman ditch. This was of a reasonable size, and extended beyond the site of the excavations so the full extent of the ditch and what it could have enclosed were not found at the time.

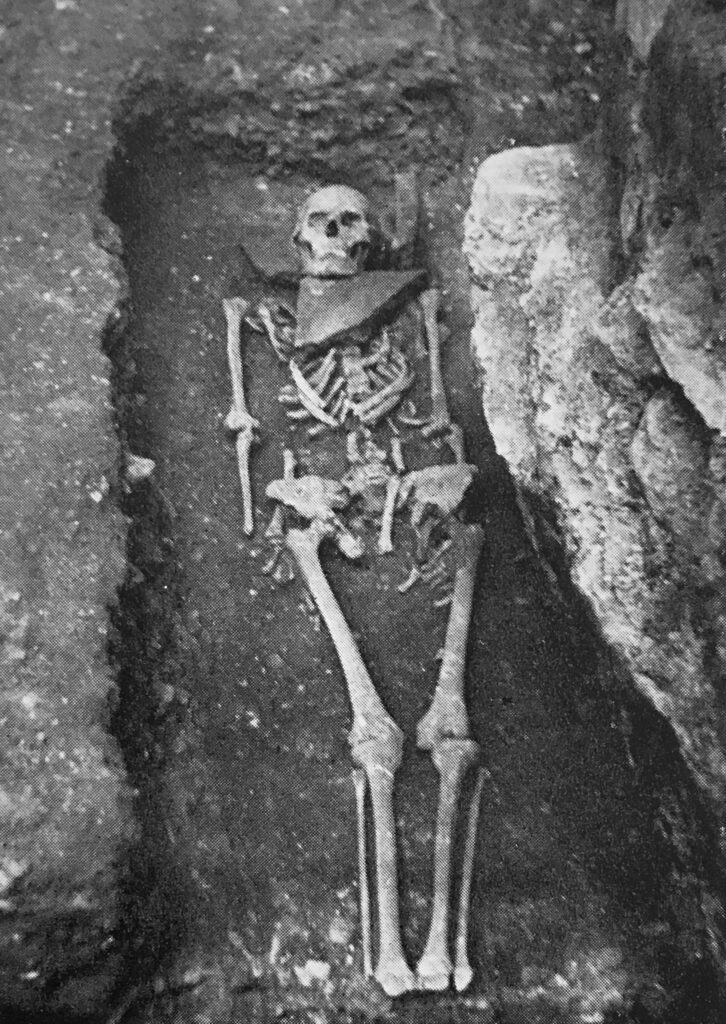

There was very little evidence of an early Christian church on the site of St Bride’s, although a number of burials were found which were probably early Christian. Evidence of either a cemetery on the site, or buried alongside an early church.

The following photo shows a late Roman / early Christian burial found near the western end of the church:

Later mediaeval burials which had been cut through during later building works as the church developed:

Grimes records how the church before the Great Fire changed over the centuries, and was a more complex structure than the simple rectangular church built by Wren on the site.

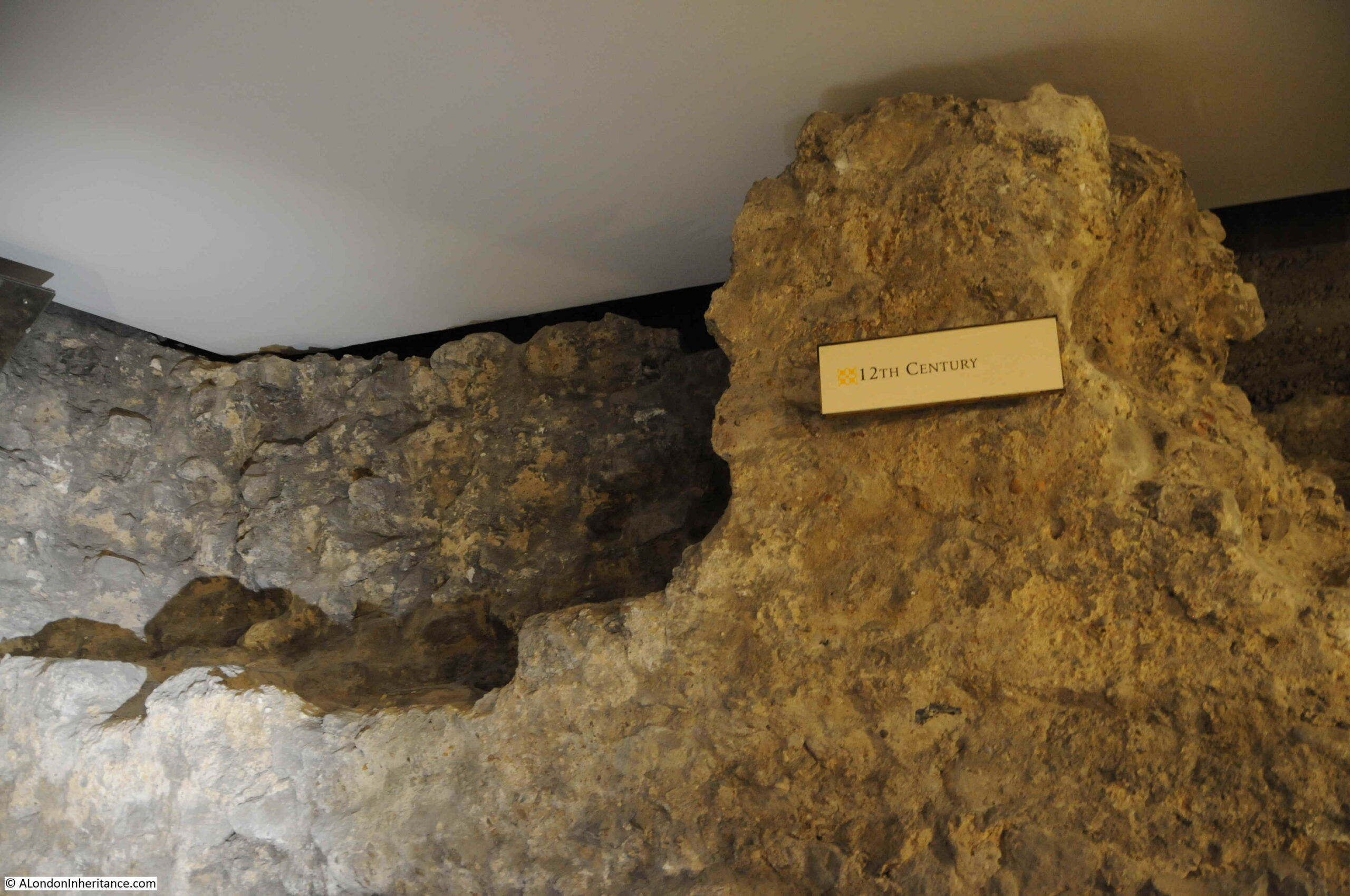

Excavations were able to provide dates to the structures found within the crypt, and these are labelled as we walk around the crypt today. Some of the earliest walls from the 12th century:

And the 11th century:

Grimes records that the earliest tower may not have been in the same location as the current tower. An early tower was probable given that St Bride’s is one of the churches recorded as sounding the curfew in the fourteenth century, however it may have been separate to the main church to avoid putting too much strain on what was a comparatively slight structure of the early medieval church.

Grimes summarises that the “the presence of an early church here with a Celtic dedication owes something to the use of the area as a burial ground since Roman times has much in it that is attractive”.

Having seen the crypt, the Roman floor, and read Grimes’ comments about the natural gravel on which the floor was probably built, a second look outside the church is instructive. The following view is looking along St Brides Avenue, which as can be seen, is lower than the church:

In the following photo, I am looking back up St Bride’s Avenue from the east. This view shows the gradual increase in height towards the western end of the church.

The Old Bell on the right, is an old pub, claiming to have been built by Sir Christopher Wren in the 1670s for workmen and masons working on the church of St Bride’s.

The following view is looking along Bride Lane at the eastern end of the church, showing how high the church is, compared to the ground level at the east.

As Grimes gives the level of the Roman floor as about 10 feet below Wren’s church floor, the level of the Roman floor and the natural gravel is probably at the same level as Bride Lane.

This is rather unusual, as there is usually a depth of “made ground” (the artificial deposits of human occupation that raise the level of the ground) in London between the natural surface, Roman remains, and the surface level of today.

It could be that as St Bride’s was built on the western banks of the River Fleet (see the earlier Rocque map extract for the location of the Fleet), that the descending gravels found by Grimes from west to east were part of the bank towards the river, and this gave less opportunity for man made deposits to build up.

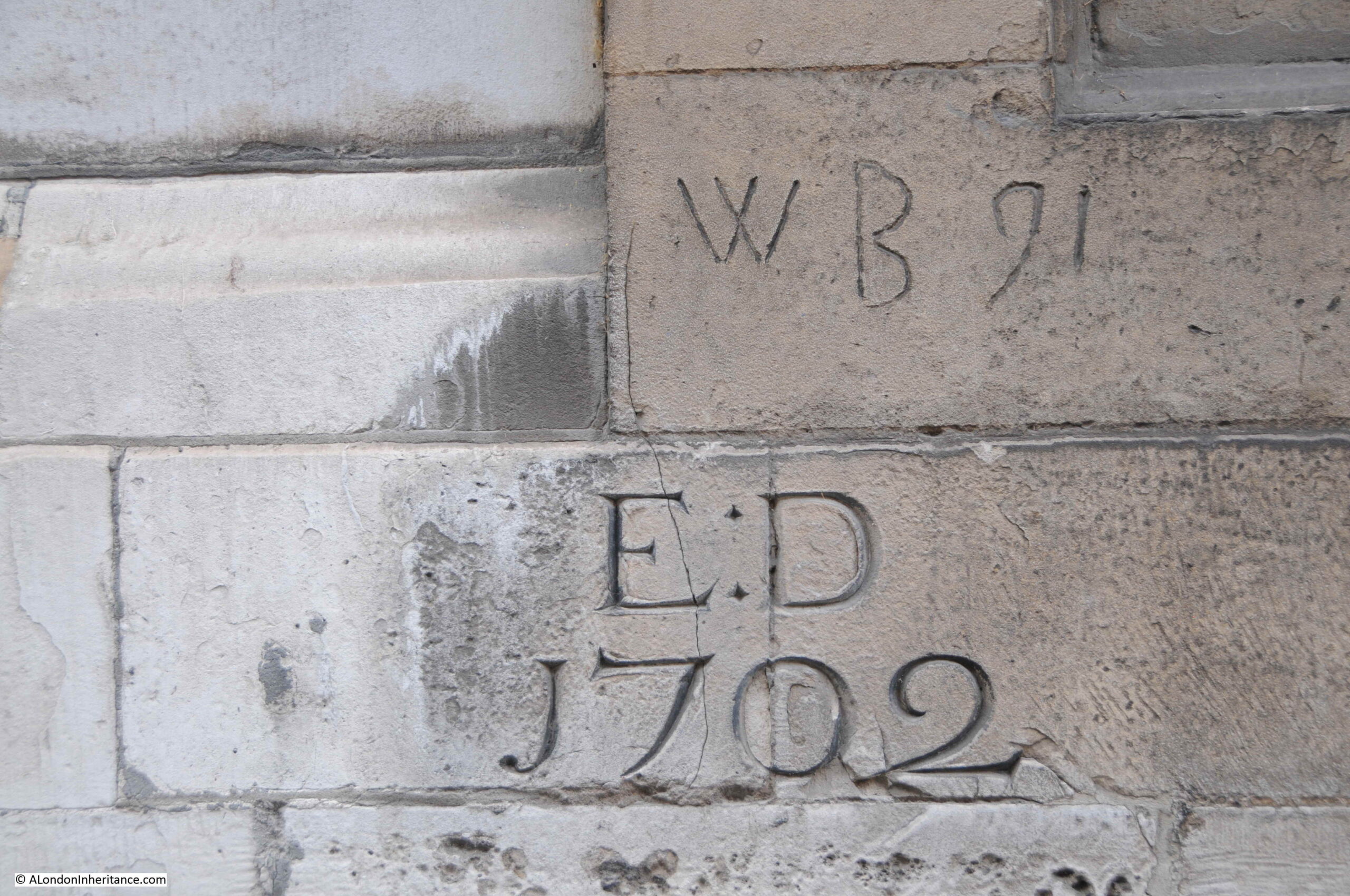

Walking around the outside of the church, and there are a number of carvings on the church, including the following by or to E.D. and dated 1702 – the time when the tower of the church was being completed.

I did find a number of interesting references to St Bride’s when researching newspaper archives. One of the earliest dates from the 9th of August, 1716, where deaths in the City of London were reported.

One of these deaths was a person “Killed by several bullets, shot from a Blunderbuss at St Brides” – which raises all manner of questions, sadly not answered in the newspaper.

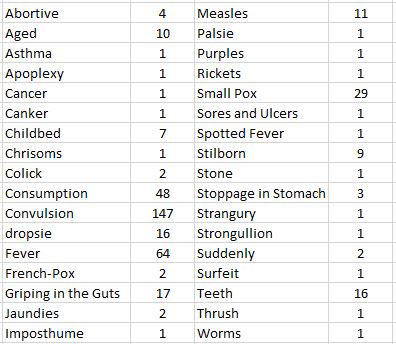

The death was part of the Bills of Mortality, records of deaths in London, along with their cause (and an example of how I am easily distracted when researching topics). The following table is the Bill of Mortality for London for the week from the 24th to the 31st of July, 1716:

Causes of death were much more descriptive of their actual perceived cause in the 18th century.

The names of some need a bit of deciphering, for example “Chrisoms”.

A Chrisom was a piece of cloth laid over a child’s head when they were being baptised or christened, and would have probably been used at St Bride’s. The term was also used to describe the death of a child if they had died within a month of their baptism.

Bills of Mortality show a story over time, recording the causes and number of deaths of Londoners – a topic for a future post.

St Bride’s is a fascinating church, one of a few that have a Roman floor in their crypt. All Hallows by the Tower is another church where evidence of Roman buildings can be seen in the crypt (see this post).

A history that is almost 2,000 years old, and with a role that is relevant today, providing a spiritual home to the publishing industries and those following the profession of journalism, where journalists continue to report from war zones across the world.

If you are in the vicinity of Fleet Street, St Bride’s is very much worth a visit.

I had hoped to cover Bridewell, which was just to the south of the church (as can be seen in the Rocque map), but ran out of time – also a topic for a future post.