Christopher Wren, London Transport and St. Mary Aldermary – there is an obvious link between two of those subjects, but London Transport looks out of place, hopefully it will become clear.

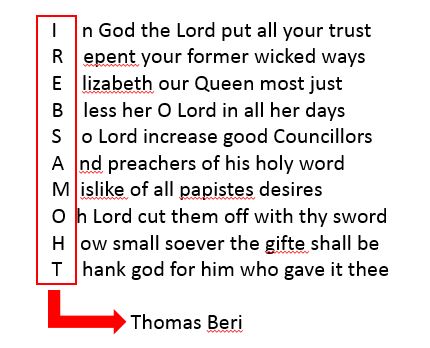

One of the pleasures of buying second hand books is not just the book, but what can be found in the book. A few years ago, I purchased the book “Wren and His Place In European Architecture” by Eduard Sekler.

There is no publication date listed in the book for the edition I found in the bookshop in Chichester, however at the end of the preface to the book, the date August 1954 is given, so the book possibly dates from the mid 1950s.

The purpose of the book was to “promote a better understanding of Wren’s work as an architect by relating it t contemporary architectural activity on the Continent and Wren’s own intellectual and spiritual background” – a task that it does rather well.

The bonus with the book, was what was tucked in between the pages, a small booklet published by London Transport in 1957:

The booklet was one of a number published by London Transport which had the underlying aim of encouraging people to get out and explore the city. and to “Make the most of your public transport”.

The Latin “Si monmentum requiris, circumspice” is taken from Wren’s tomb in St. Paul’s Cathedral, and which translates as “If you seek his monument, look around you”.

The use of the phrase on the tomb is meant to refer to the cathedral which Wren designed, but in this case, London Transport have admitted that this is freely translated to making the most of your public transport, presumably to explore London to find the many buildings designed by Christopher Wren which are also his monuments.

The London Transport booklet is a 19 page guide to the architecture of Christopher Wren, in and near London:

The booklet is organised into 7 chapters, which cover:

- Chapter 1 – An overview of Christopher Wren

- Chapter 2 – Architect, an overview of Wren’s work

- Chapter 3 – St. Paul’s Cathedral

- Chapter 4 – City Churches

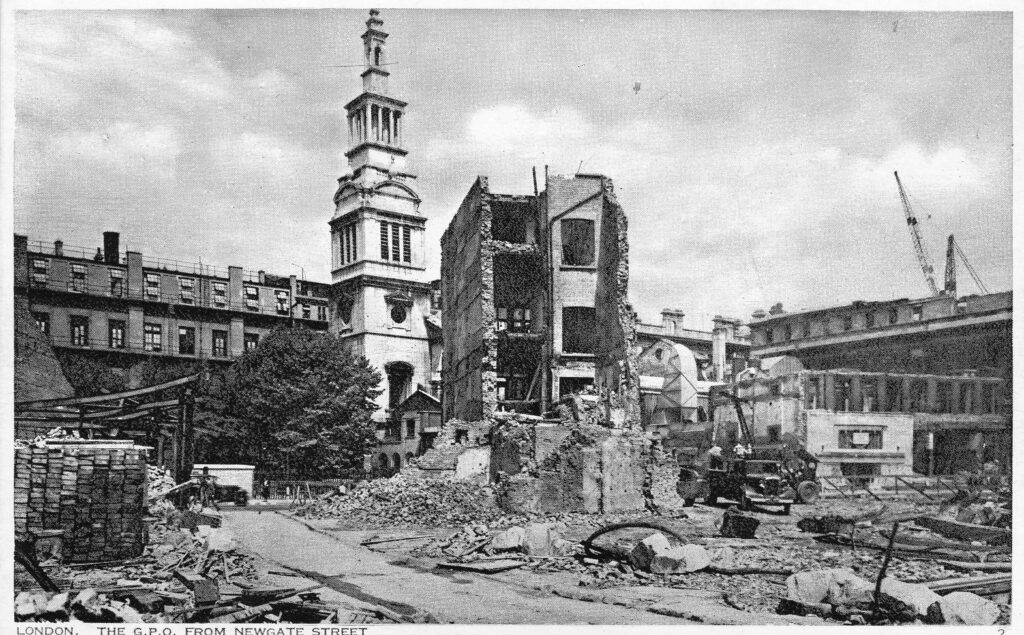

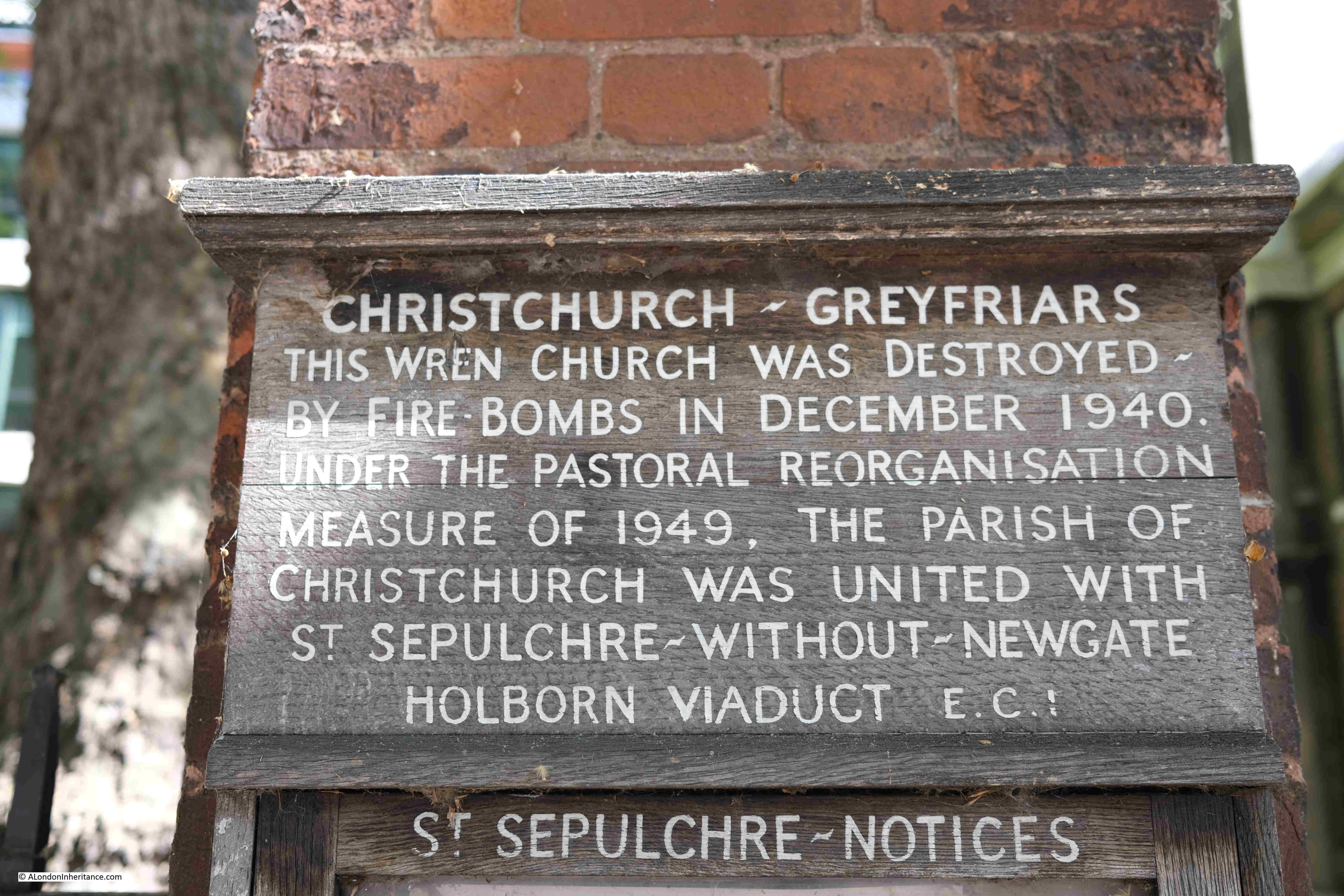

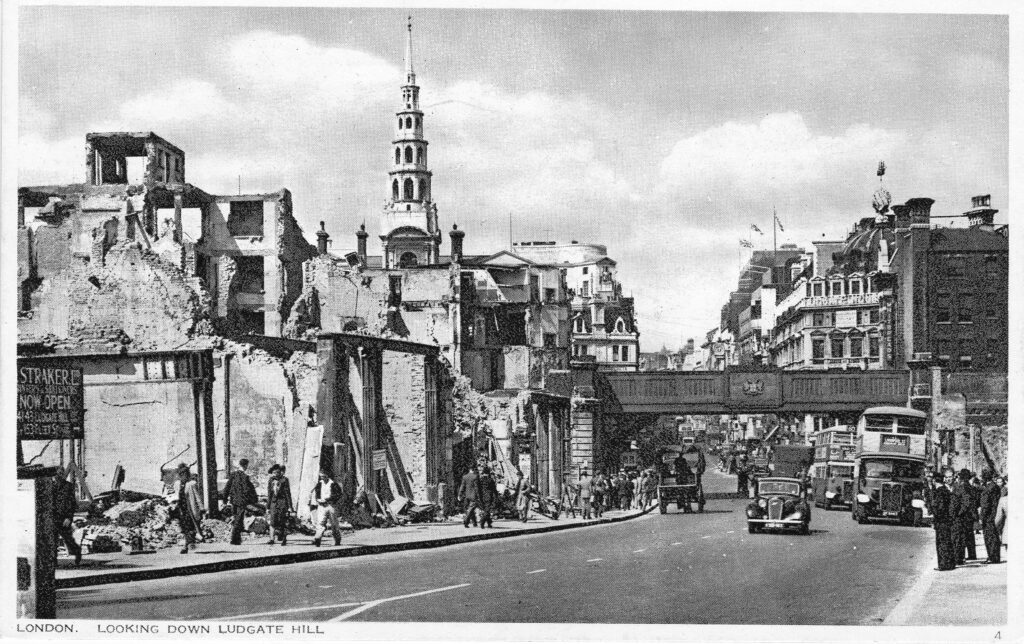

- Chapter 5 – Remnants, Wren’s churches that still survive although their fabric had been devastated by bomb damage

- Chapter 6 – Secular Buildings, Including Chelsea Hospital, Morden College and the Royal Naval Hospital etc.

- Chapter 7 – How to get there, underground stations, bus routes and trains to use to get to the places mentioned in the booklet

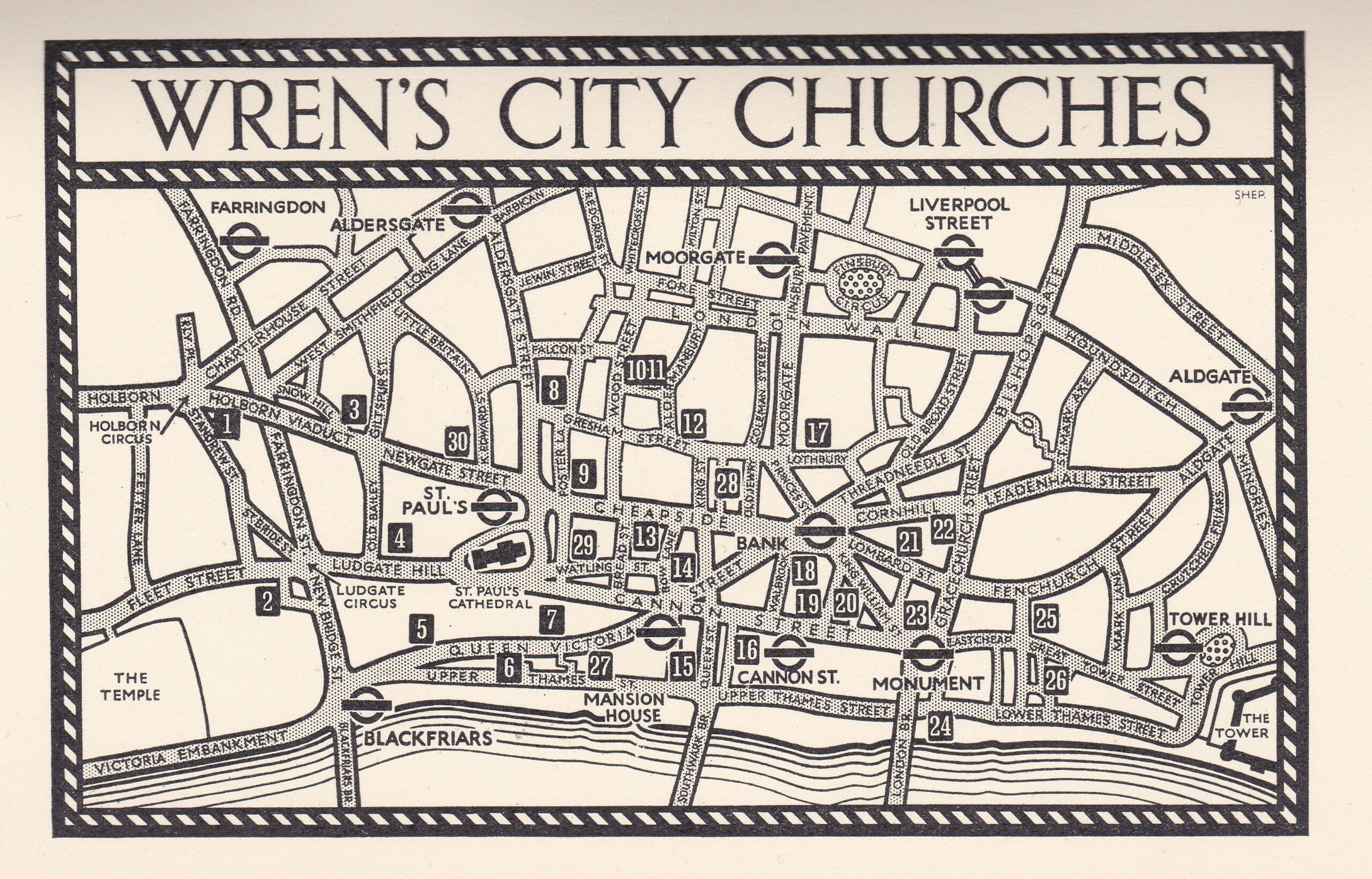

At the back of the booklet, there is a map showing Wren’s City Churches, along with Underground Stations, so the visitor could work out which station to use to visit some of Wren’s City churches:

It is a wonderful little booklet, and an example of when London Transport probably had more of a budget for publications and maps aimed at encouraging people to make more use of the city’s transport network.

This year would have been an ideal time for an updated booklet, as this year it is 300 years since Christopher Wren’s death in 1723.

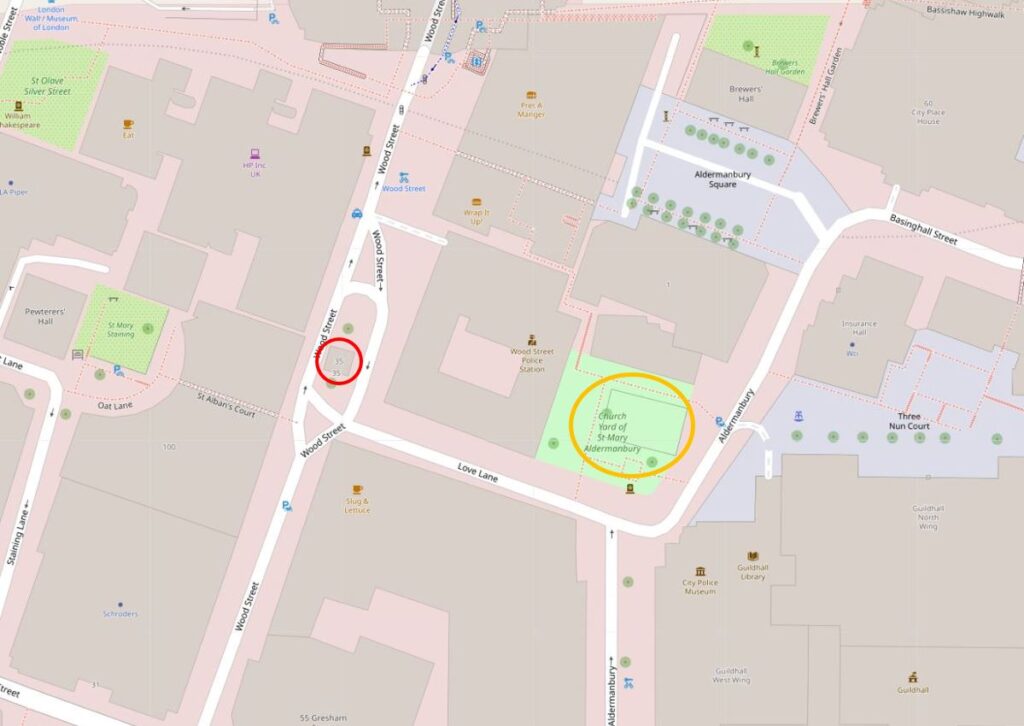

At the start of the year, I had been intending to follow the advice of the booklet and visit all of Wren’s City churches for a series of blog posts, however time and poor planning has forced that idea to be abandoned, so to link the London Transport booklet with one of Wren’s churches, I had a look around a church I have not written about before – St. Mary Aldermary.

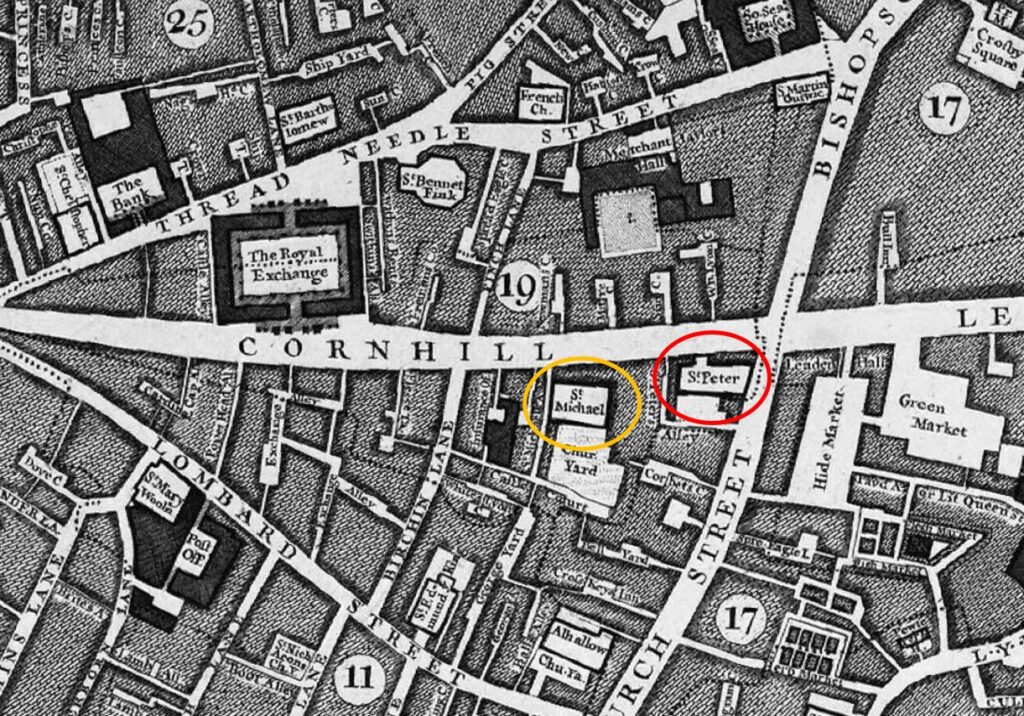

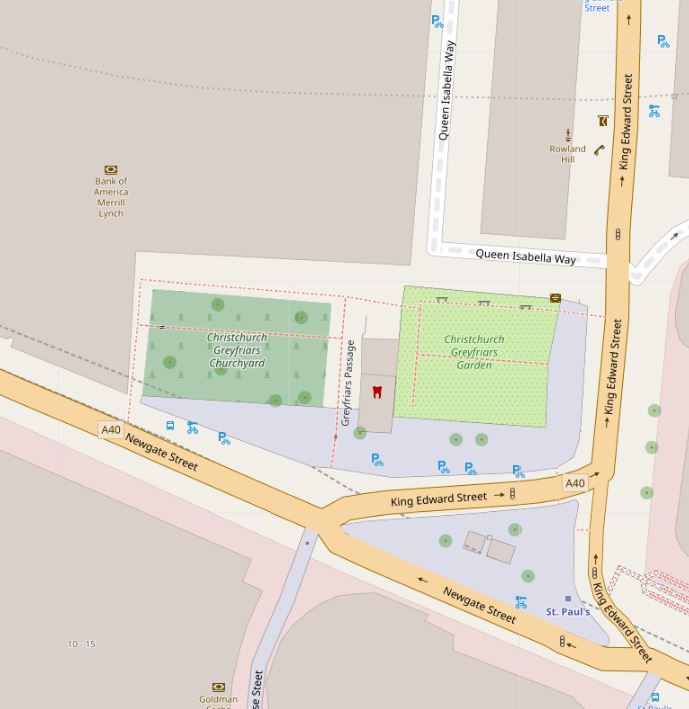

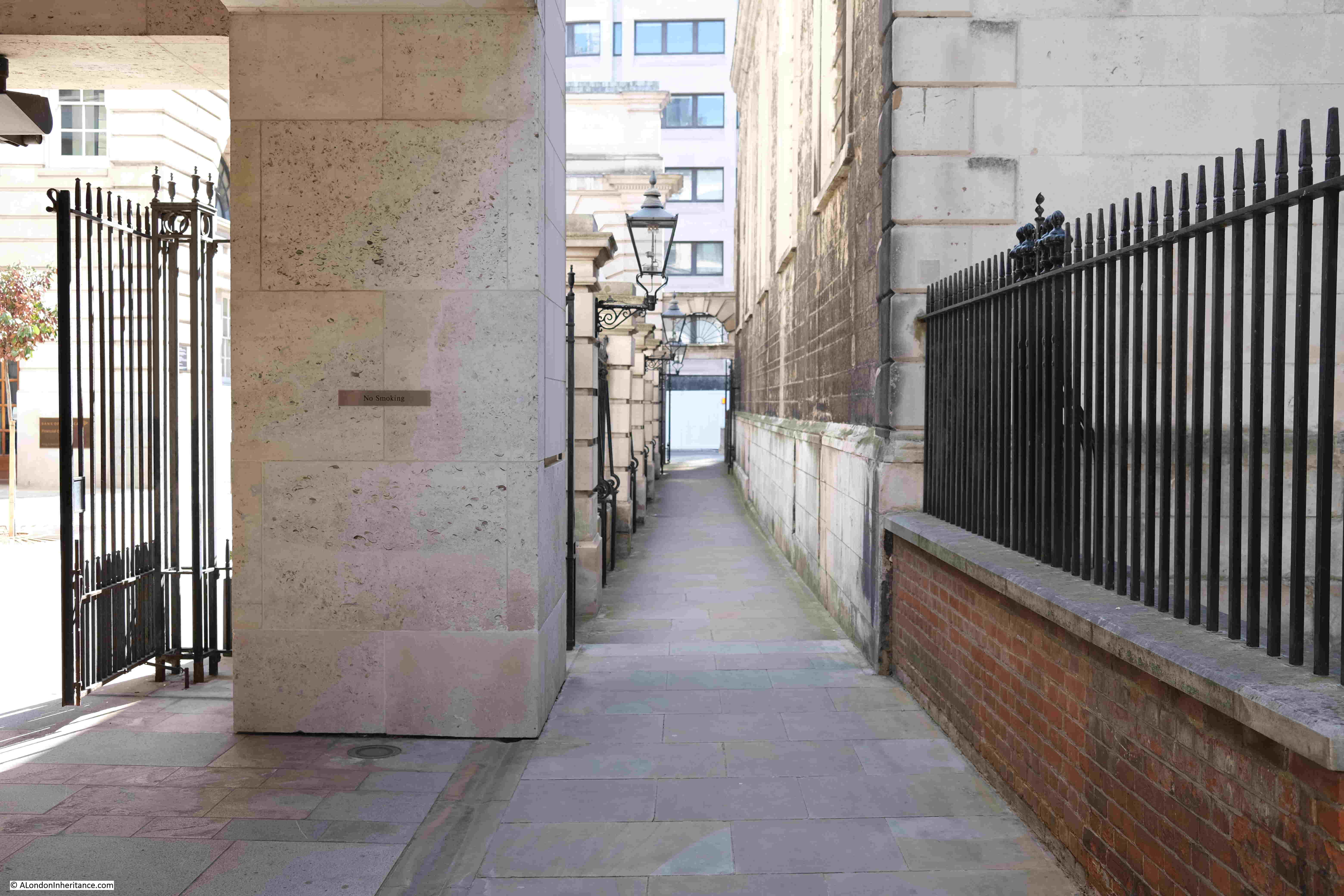

The church is located within a triangle of land, with Queen Victoria Street, Bow Lane and Watling Street forming the three sides of the triangle. The church is at a strange angle to Queen Victoria Street and is also hemmed in by surrounding buildings:

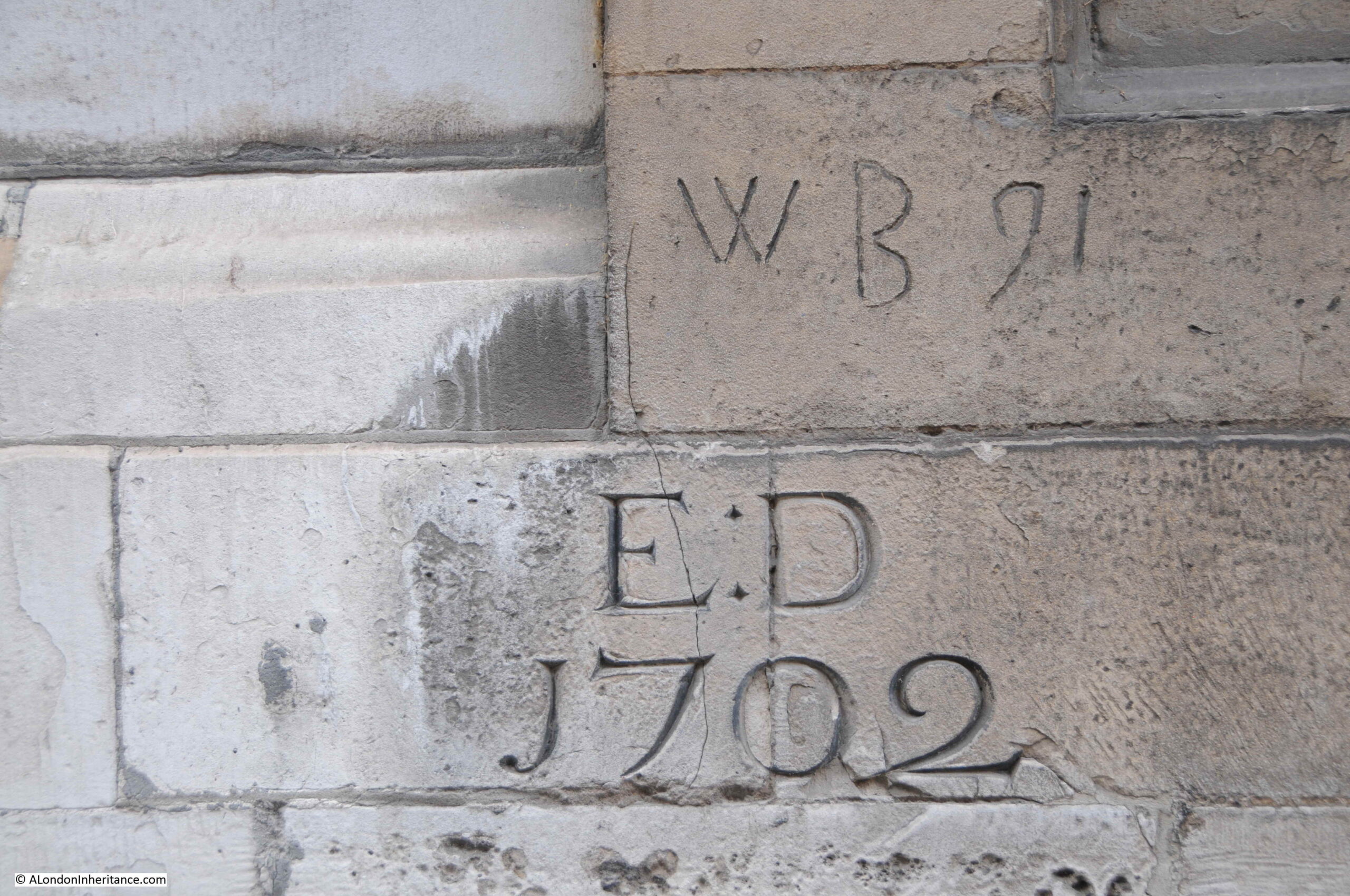

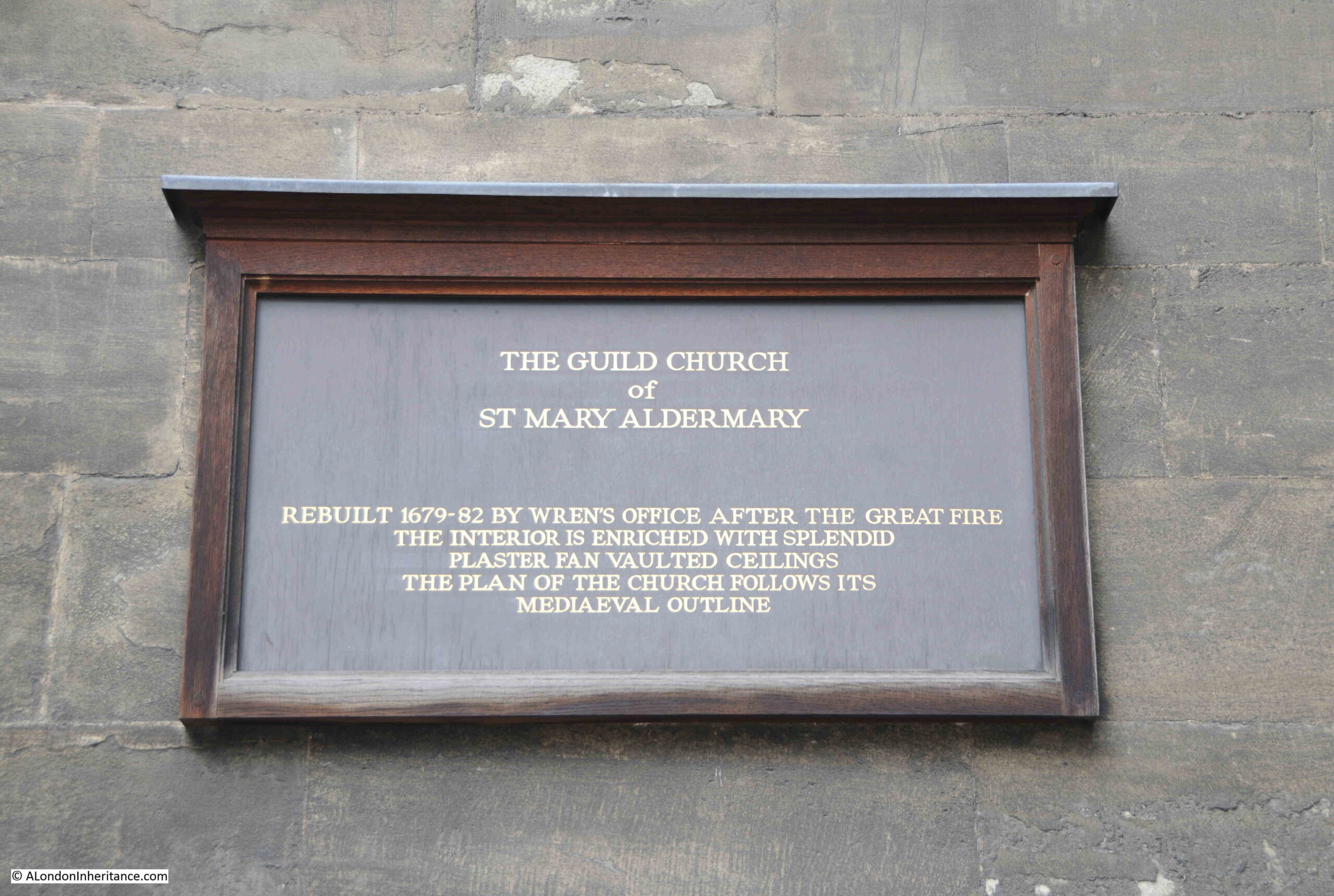

A plaque on the church hints at why the church is positioned as it is, as it follows its mediaeval outline:

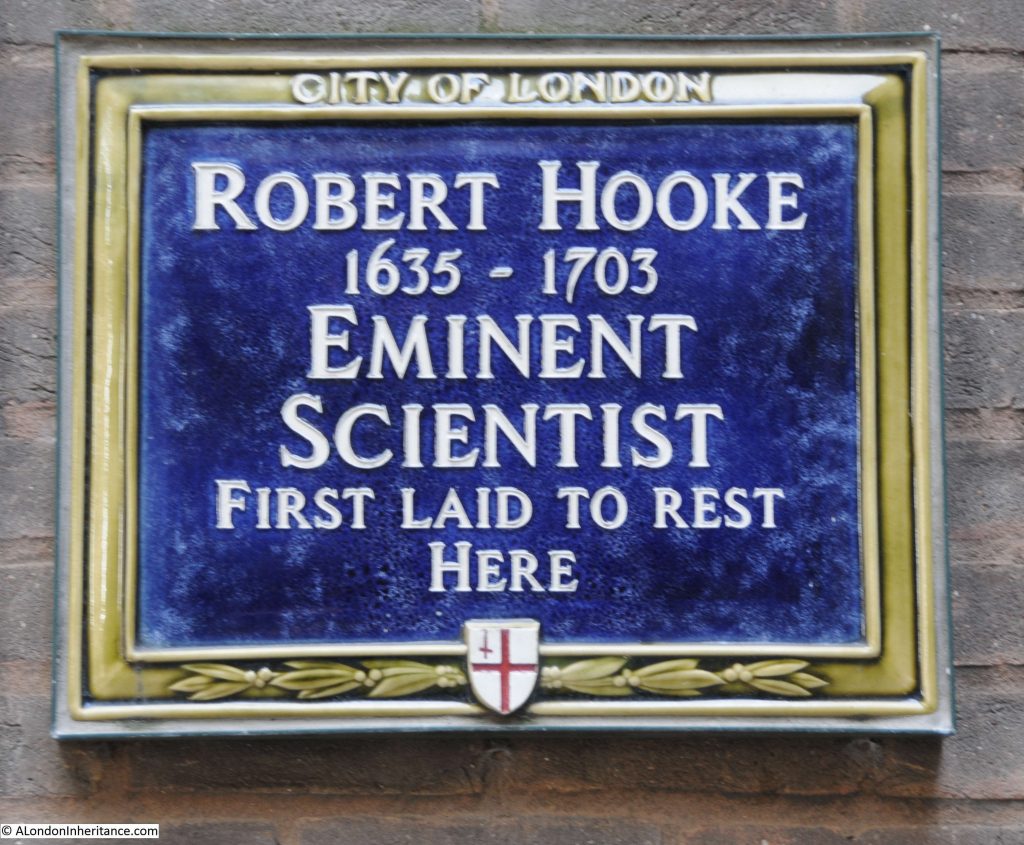

The plaque also states that the church was rebuilt between 1679 and 1682 by “Wren’s Office”. This is an interesting phrase as it does hint at the question of how much Wren was involved in the buildings attributed to him.

The amount of post Great Fire rebuilding, along with all his other building projects, interests and responsibilities must have meant that for many of his buildings, whilst he was probably responsible for the overall design, he had others working on the detail and overseeing the construction of the buildings.

The following photo is looking along Queen Victoria Street as it heads down towards Blackfriars. Part of the church can be seen on the right and a narrow building making use of a small plot of land between street and church can be seen in the middle.

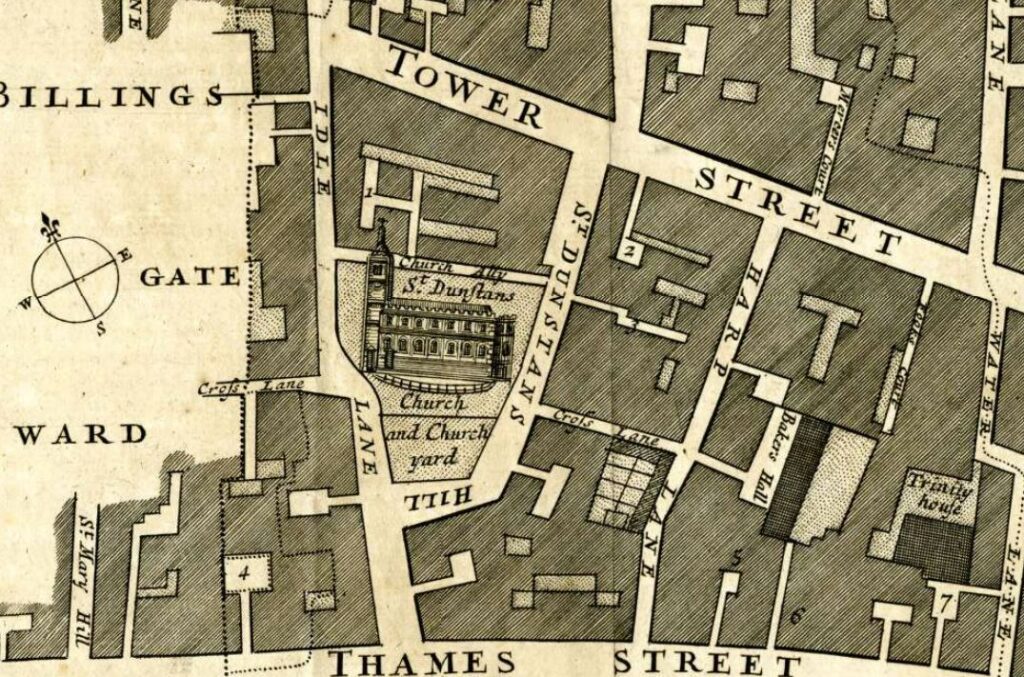

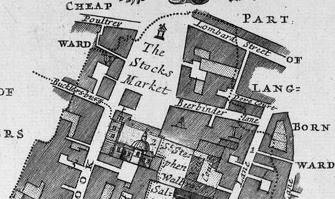

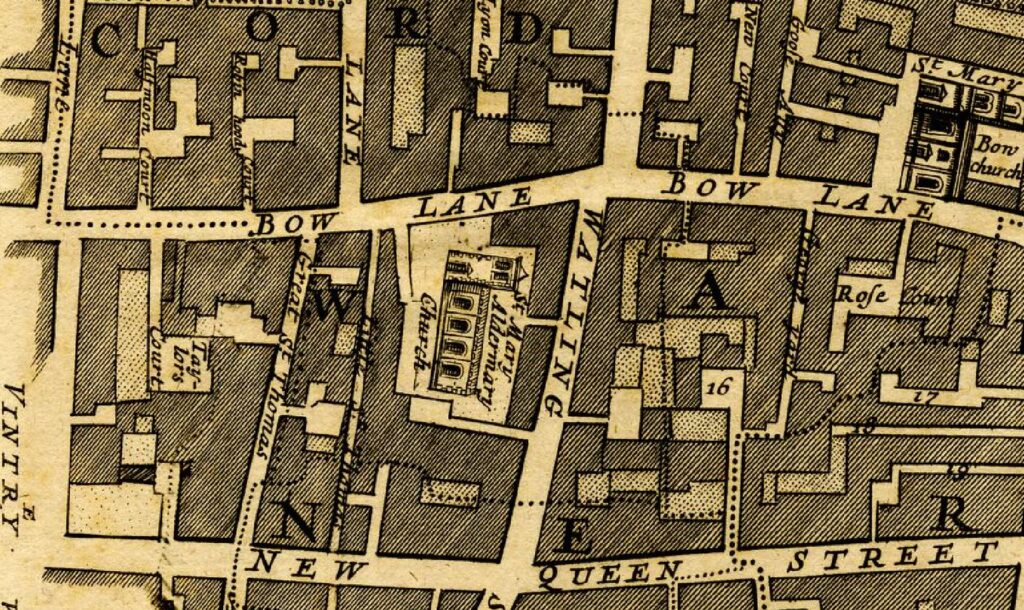

The following map is an extract from a map of Bread Street Ward and Cordwainer Ward, dated 1754 and for an edition of Stow’s Survey of London. The map shows St. Mary Aldermary in the centre, with Bow Lane at the front of the church and Watling Street to the right.

The map shows the church within a typical City streetscape, surrounded by buildings, streets and narrow lanes.

The reason for the strange triangular plot of land on which the church sits today is down to the 19th century construction of Queen Victoria Street, when this wide street was carved through a dense network of streets, as part of Victorian “improvements” to the City, with the aim of providing a fast route from the large junction at the Bank, down to the newly constructed Embankment.

In Watling Street, the side of the church is more visible:

Entrance to St. Mary Aldermary in Bow Lane:

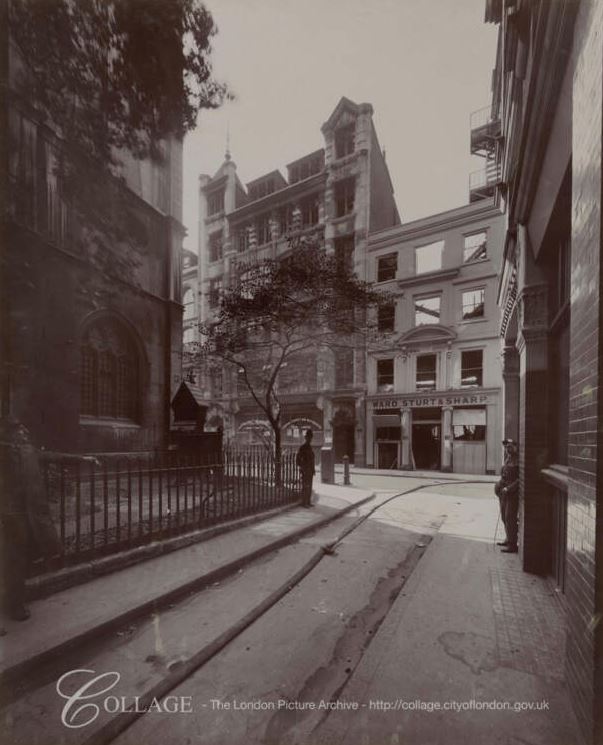

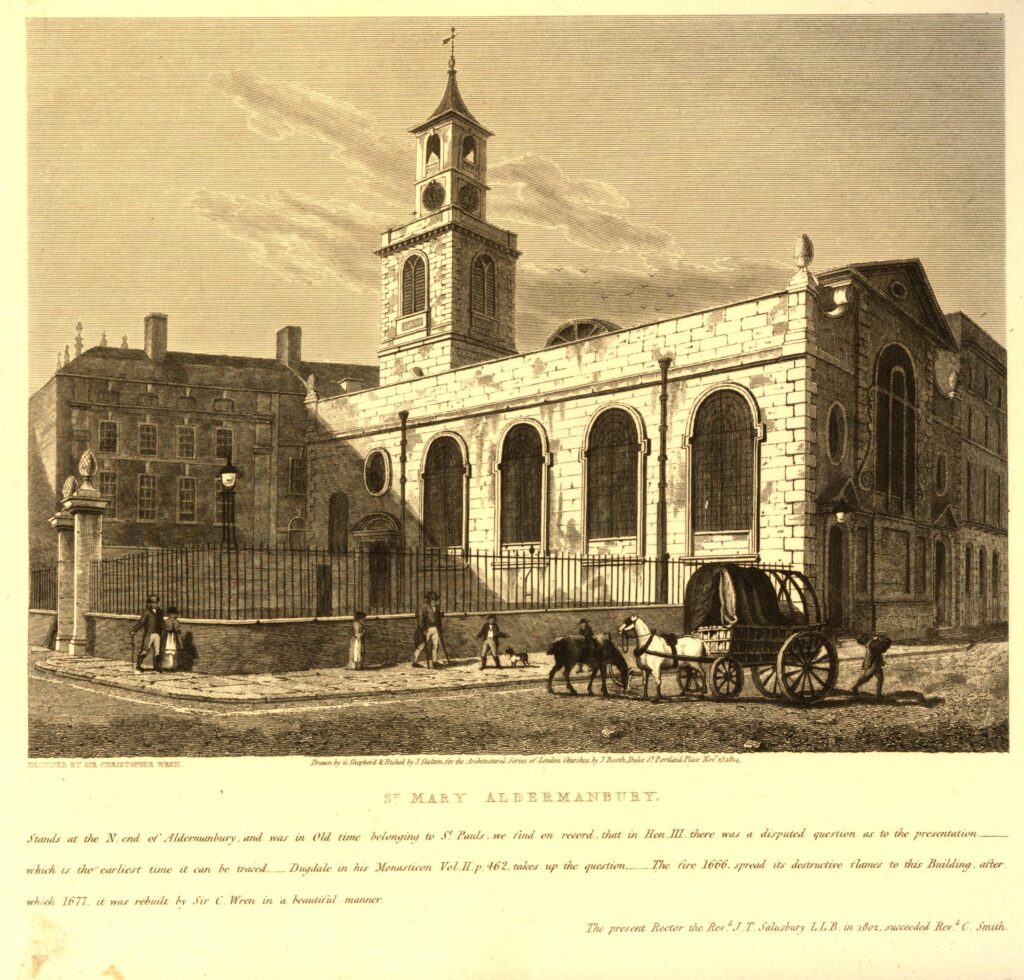

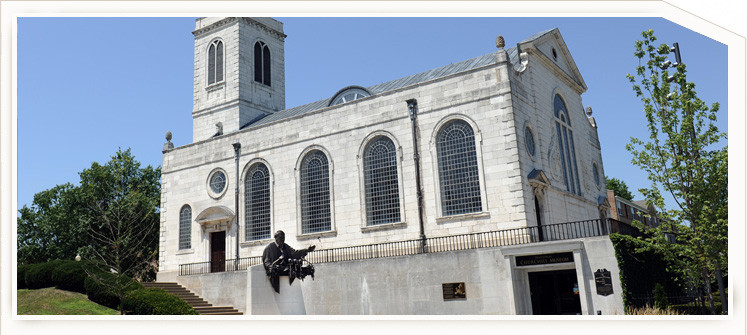

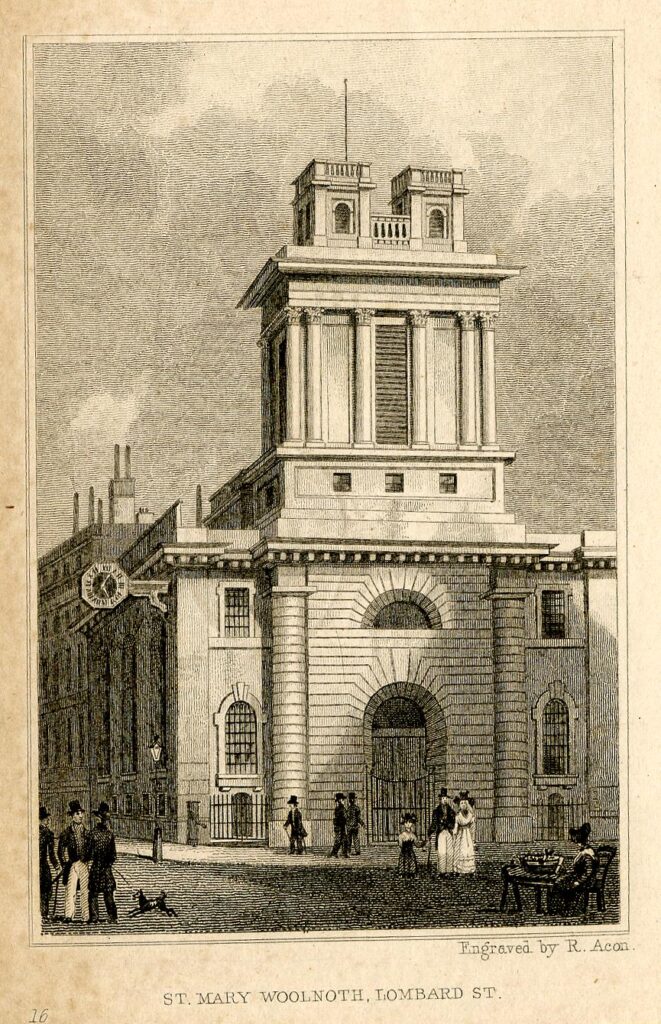

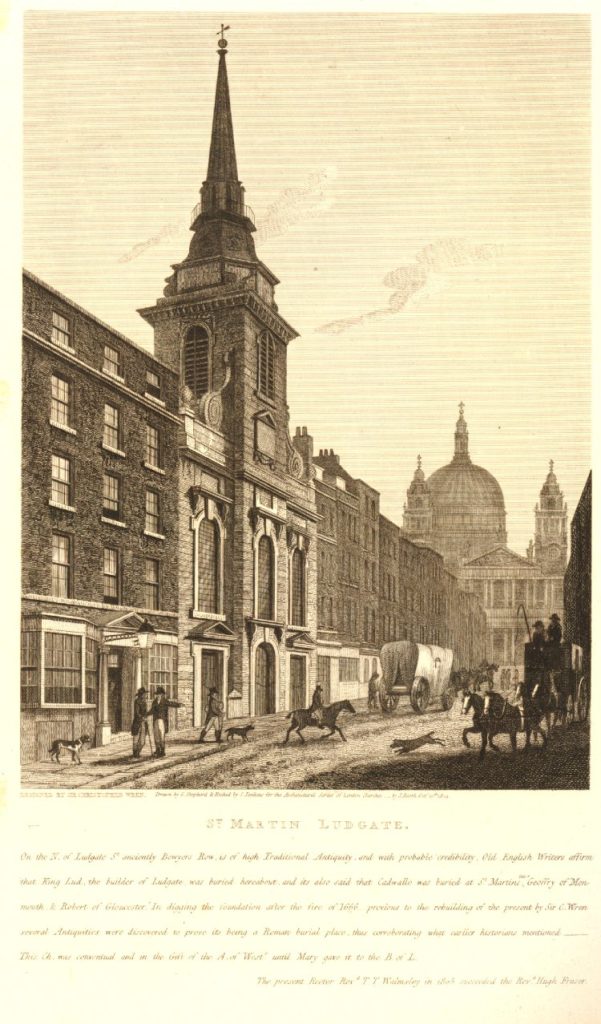

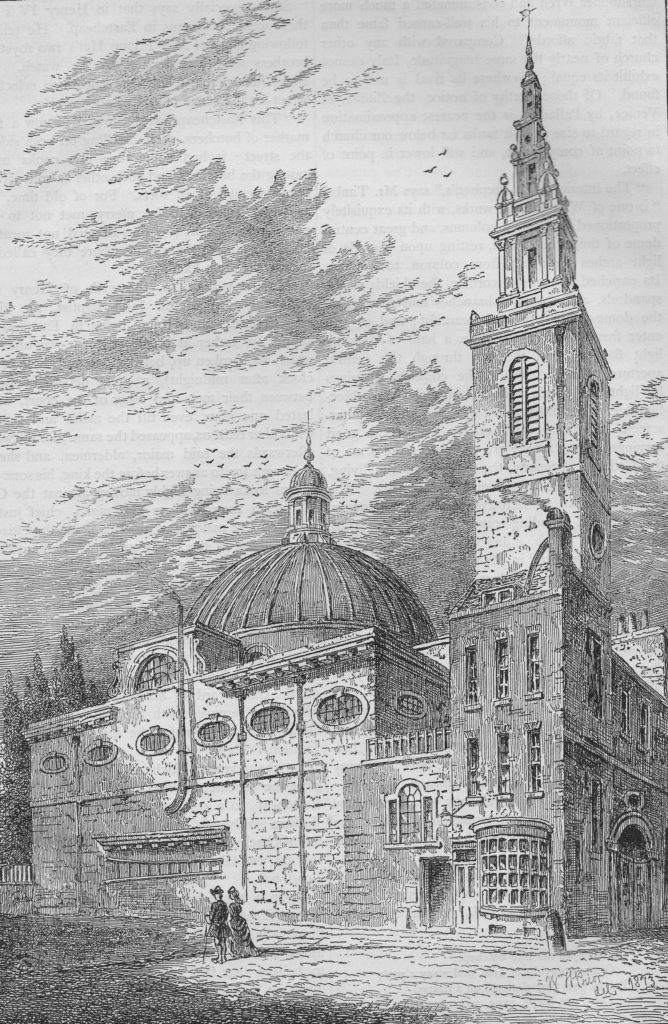

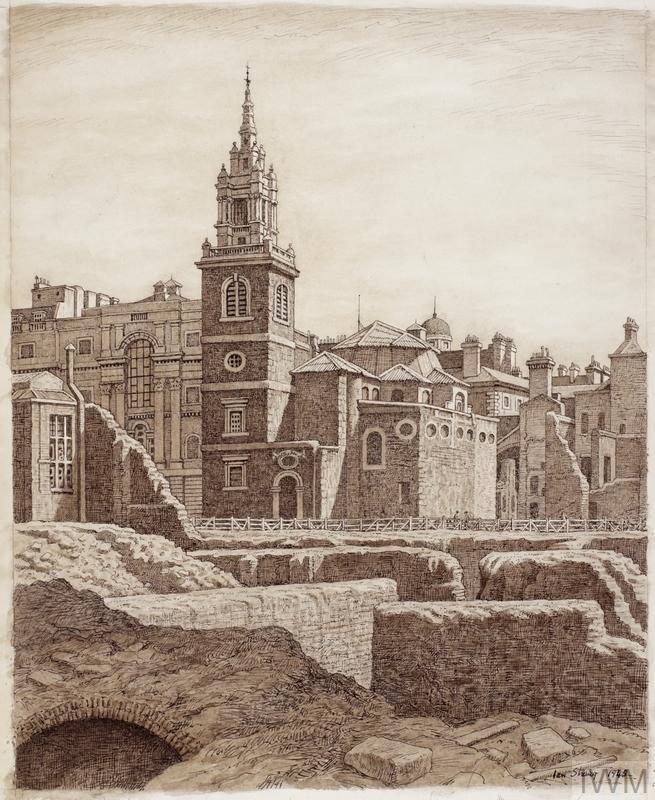

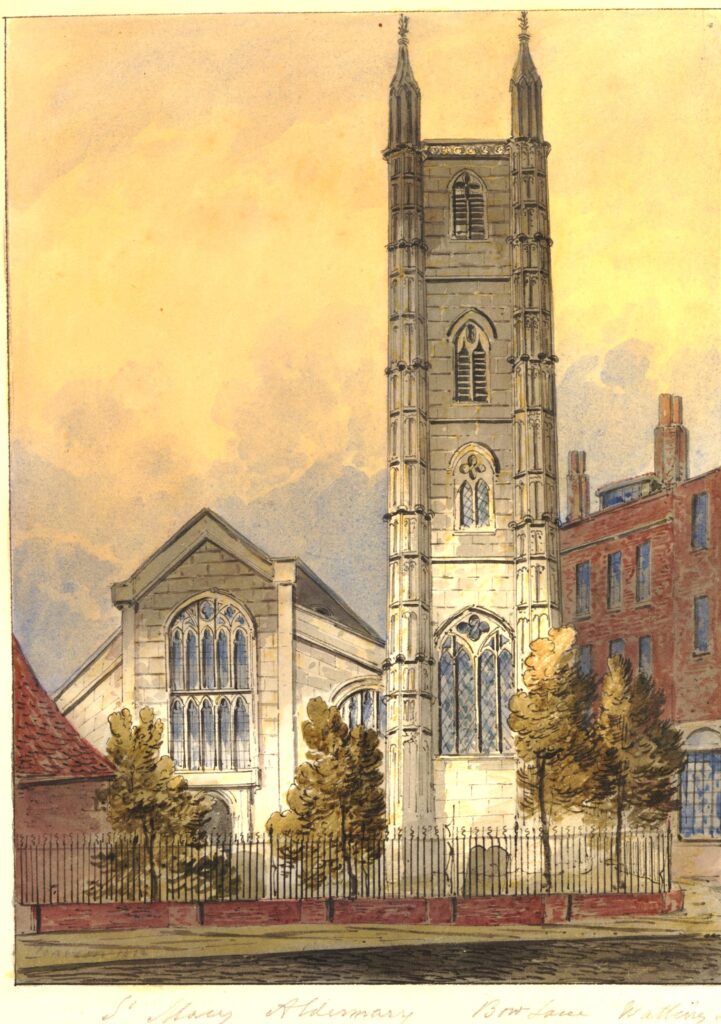

Due to the narrowness of the street, it is impossible to get a photograph of the church showing the front façade and tower. The following print from 1812 provides a view of the church which is impossible to get today:

The trees and railings have gone, as has the building on the left, however the rest of the church looks the same, the lower part of the church can be compared with my photo above.

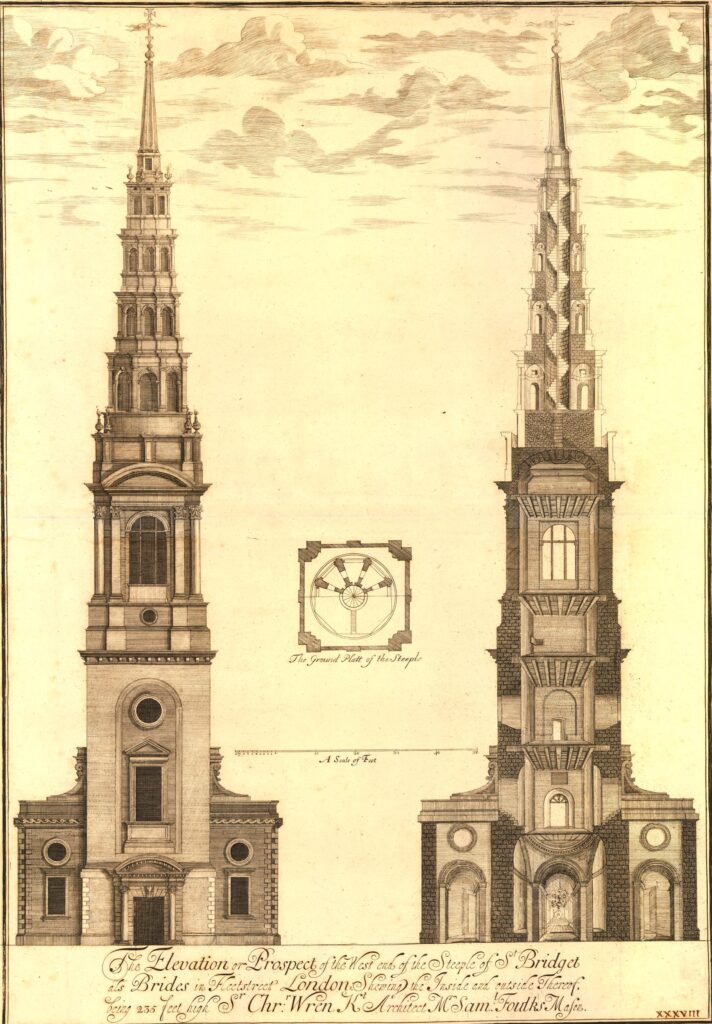

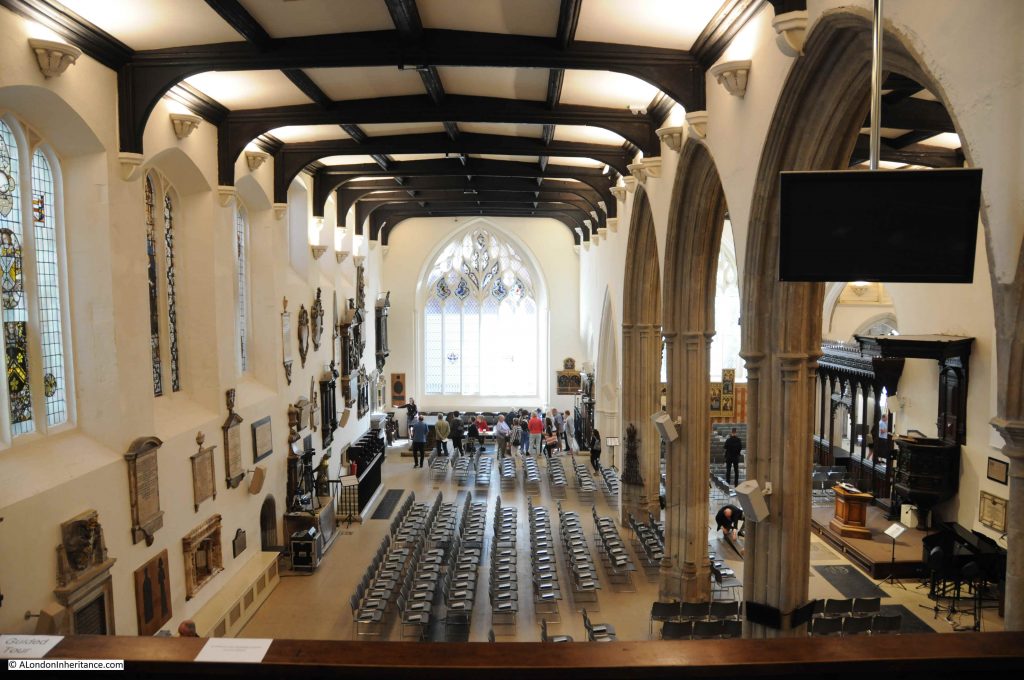

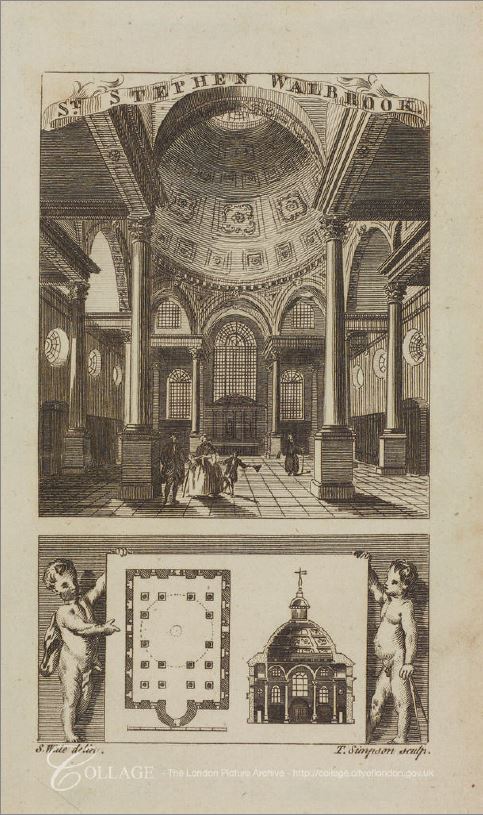

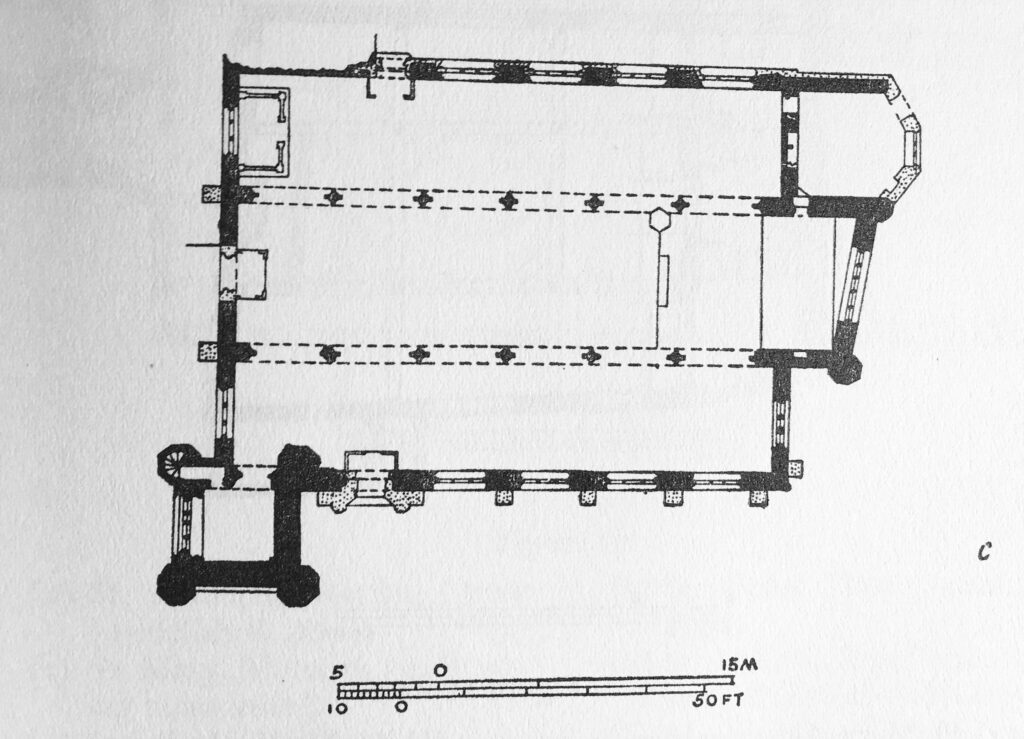

In the above print, the body of the church is to the left and the tower on the right. The book on Wren in which I found the London Transport booklet, includes a floor plan of all of Wren’s City of London churches, and it is surprising just how much variety there is across his City churches.

The floor plan for St. Mary Aldermary from the book is shown below:

The floor plan clearly shows the location of the square tower at bottom left of the plan.

The church has a Gothic feel to the design, and according the Eduard Sekler, in the book on Wren, he had an “obligation to deviate from a better style”, because the patron who was funding the rebuild of the church insisted that it was rebuilt as an exact copy of the church that was destroyed in the Great Fire.

The book “If Stones Could Speak” by F. St. Aubyn-Brisbane (1929) states that the patron was a certain Henry Rogers, who had bequeathed £5,000 towards the expense of rebuilding, and it was his widow who insisted that the church was rebuilt as an exact imitation of the former church. It does not state why this was so important.

There appears to be no image of what the church looked like prior to the Great Fire, but it would seem that we are looking today on a church that is a replica of the one that stood on the site prior to 1666.

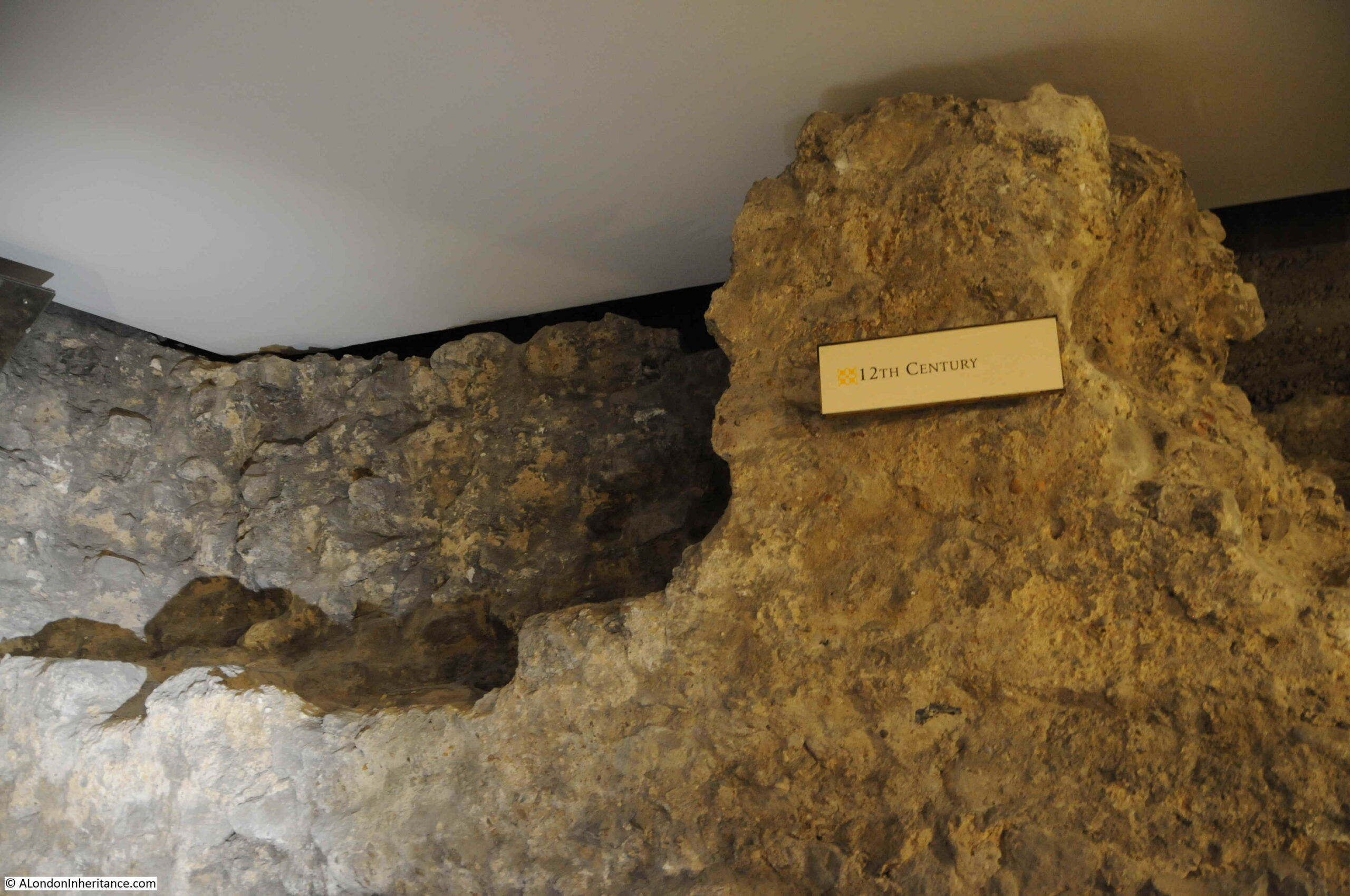

The church has a long history, with a church possibly being on the site from the 11th or early 12th centuries.

Looking through the entrance into the church from Bow Lane:

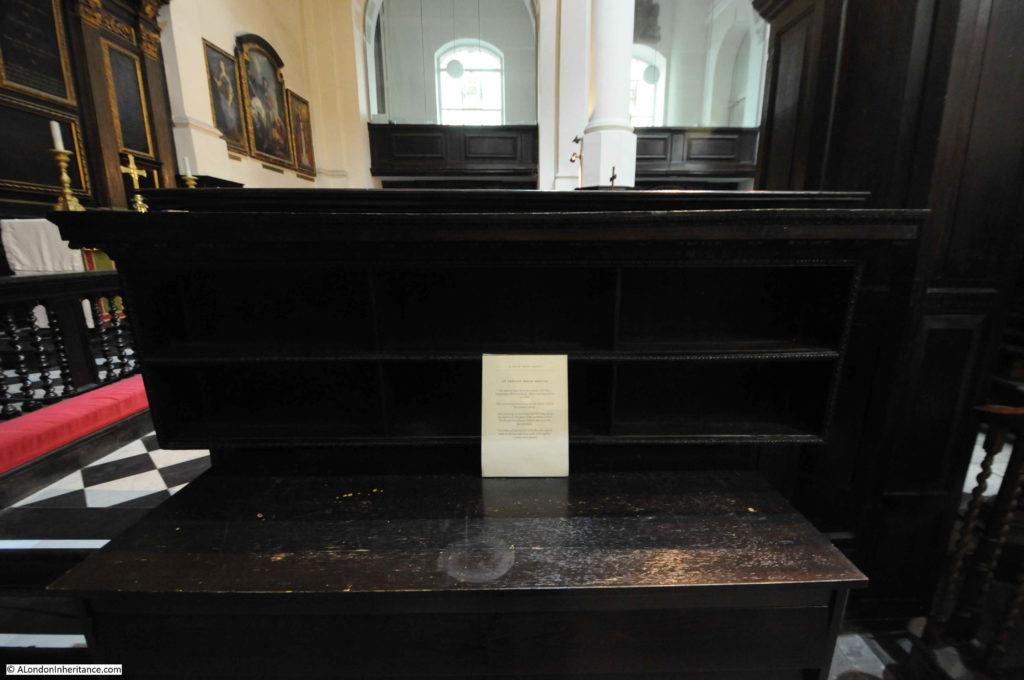

The area of the church just inside the entrance is used as a café when services are not being conducted. It is a really good place for a drink and to sit down after some miles of walking.

As shown in the image of the floor plan, the church has three aisles. The central aisle is the highest and has a magnificent plaster fan-vaulted ceiling:

View towards the altar at the eastern end of the central aisle:

In the above photo, you can see that the rear wall is at a slight angle from the rest of the church, a feature which is confirmed by the floor plan shown earlier.

A look at the ceiling:

The organ:

The following photo shows the altar and reredos (the wooden screen at the rear of the altar). As can be seen, the wooden screen is at an angle to the rear wall, to allow the screen and altar to face directly down the centre of the church despite the angled rear wall:

St. Mary Aldermary did not suffer too much damage during the last war, although much of the Victorian stained glass windows were lost.

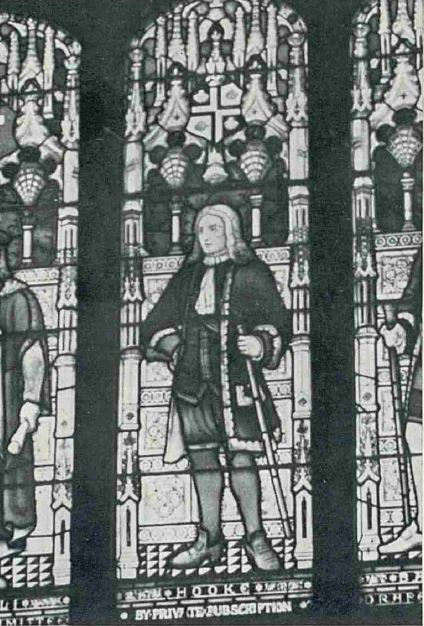

There is an interesting set of stained glass at the end of the southern aisle of the church:

At the bottom of the windows are three panels:

At the centre is an image of the church surrounded by the flames of the Great Fire. The windows to left and right record the rebuilding of the church by Christopher Wren and the amalgamation of parishes.

St. Thomas the Apostle was not rebuilt after the Great Fire and the parish was united with St. Mary.

St. John the Baptist was destroyed in the fire and the parish was united with St. Antholin’s Watling Street which was demolished in 1874 and these two parishes united with St. Mary Aldermary, so the church today is the sum of four parishes, which highlights just how many churches there were in the City prior to the Great Fire.

The Aldermary part of the name and dedication of the church is believed to come from “Older Mary” which has been assumed to indicate that it was the oldest church in the City to be dedicated to Mary, however this does seem unlikely, given that the church seems to date from around the late 11th / early 12th centuries, however given how long ago this was, and the lack of supporting documents, it is impossible to be sure.

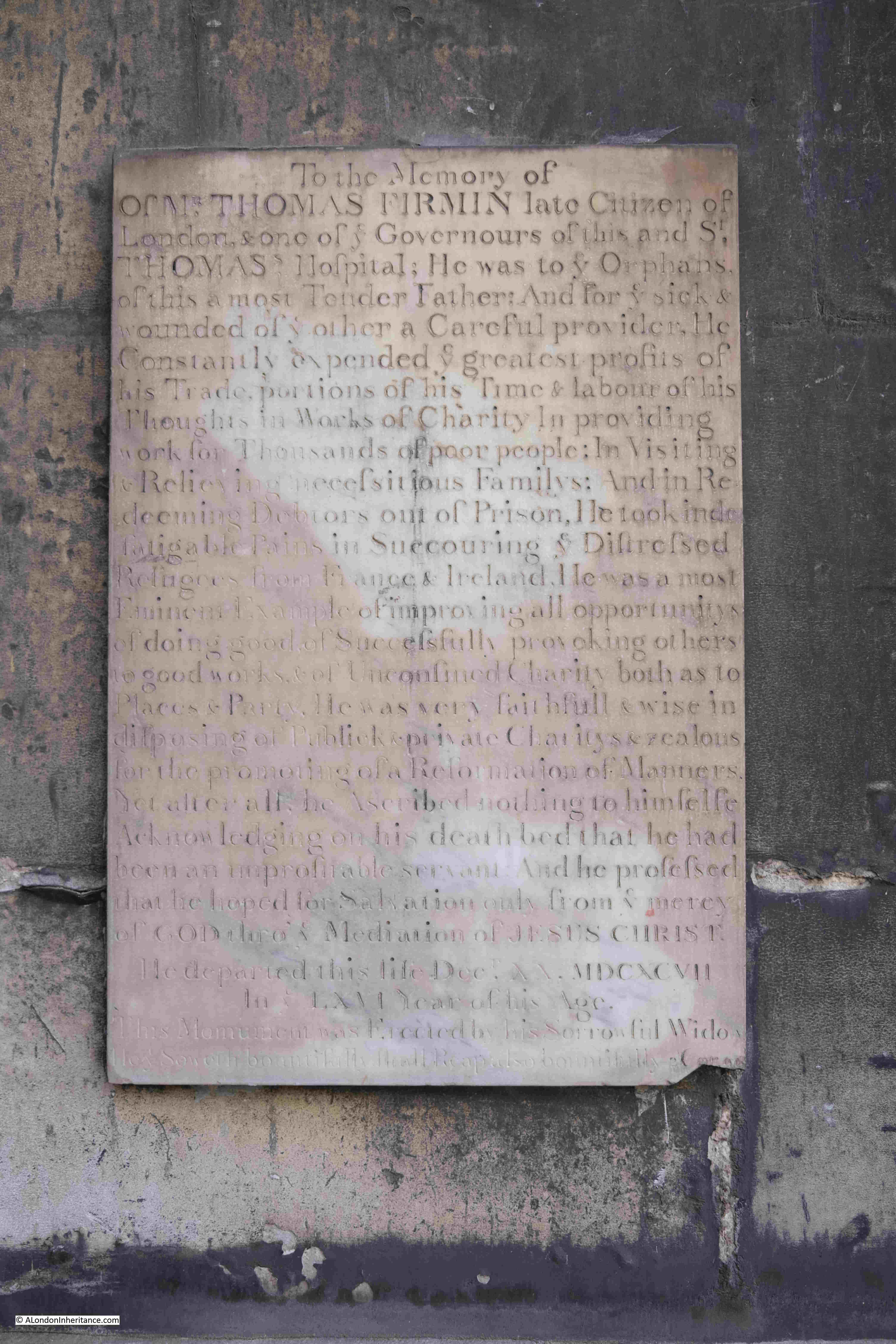

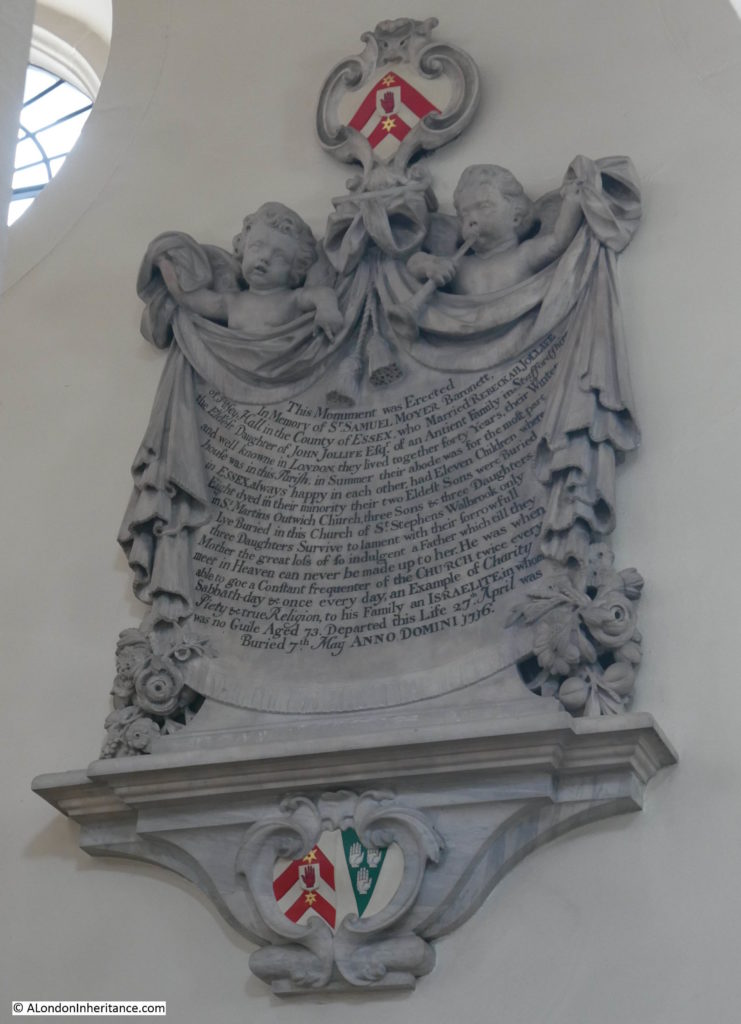

There are a number of monuments remaining in the church, and one of the more ornate of these is to a Mr. John Seale who was apparently “Late of London Merchant”. I assume there should have been a comma between London and Merchant:

City church monuments often tell stories of how those recorded travelled the world. This was off course only those who could afford to have monuments were those who were able to travel.

John Seale is recorded as being “Born in the Island of Jersey. resided many years in Bilboa in the Dominions of Spain”. He died aged 48 on the 11th of July, 1714, by when he had presumably moved to London.

The Seale’s appear to have been a long standing Jersey family, and the use of the first name of John stretched back several generations. The first John Seale was born in 1564 and as an adult was a Constable at St, Brelade, Jersey in the Channel Islands.

His son. also a john was also a Constable in Jersey. His son was also a John, and it was this John whose son was the John Seale buried in St. Mary Aldermary.

The buried John Seale also had a son called John who is recorded as being a London Merchant and Banker and who took on an apprentice from Westminster School in 1736.

The next John Seale would become a Baronet, and the Whig Member of Parliament in 1838, and although he had several children, including boys, none of them were called John.

The loss of the first name of John was only for one generation, and the name John Seale returned in 1843, and four generations later, John Robert Charters Seale is the current Seale Baronet.

A bit of monument trivia, but it is interesting that the dusty monuments in City of London churches still have traceable, living descendants.

The font, which according to the description of the church in “If Stones Could Speak”, dates to 1682, the same time as Wren’s reconstruction of the church. It was apparently a gift from one Dutton Seaman, when wealthy members of the parish would have been expected to contribute to the rebuilding and furnishing of their parish churches.

St. Mary Aldermary is a lovely church, and a small bit of Gothic among Christopher Wren’s City churches. Back to the book “Wren and His Place In European Architecture” by Eduard Sekler, and as well as the London Transport booklet, there was also a photo of a bust of Wren. On the back were notes that it was by Edward Pierce, 1673 and that it was in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford:

Christopher Wren had been knighted the year before the date of the bust, so perhaps this was to mark his becoming Sir Christopher Wren. The full bust can be seen in the Ashmolean’s imagae archive, at this link.

I have mentioned this in a previous post, but leaving bookmarks in books is something I have been doing for years, usually it is the latest London Underground map, museum or exhibition tickets etc. Hopefully something that a future owner of the book may find of interest.

I am very grateful to whoever left the 1957 London Transport guide to Wren in the city in the book.