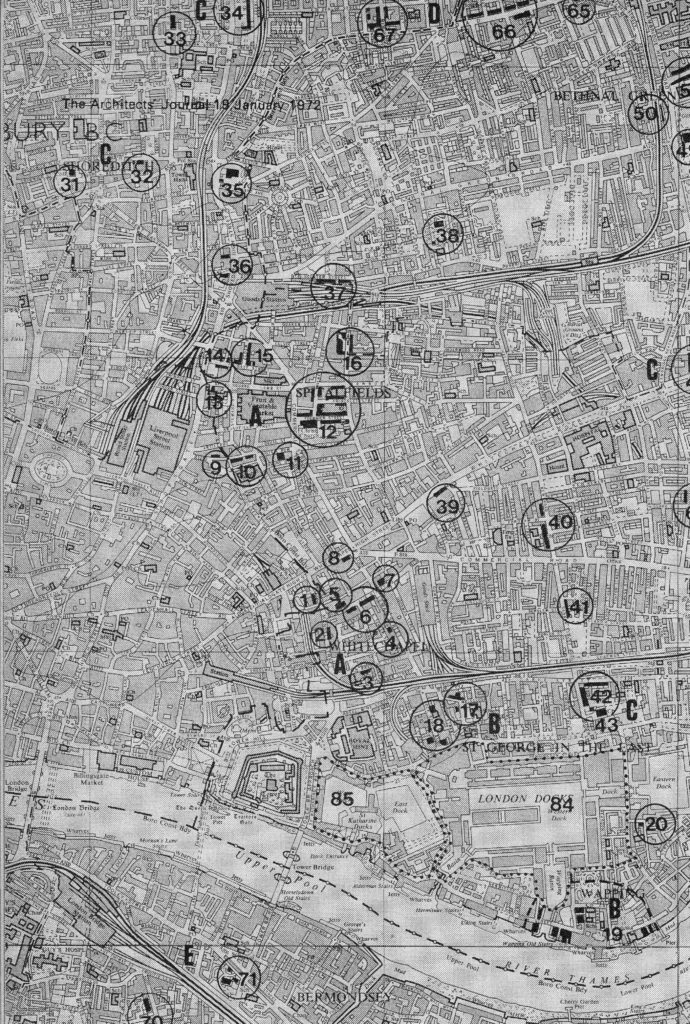

Following on from last week’s post, here is the second part of my walk through the category B sites (Medieval village centres) considered at risk in the January 1972 article “New Deal for East London” in the Architects’ Journal.

This week I am walking from site 37 (Sclater Street) to site 43 (the church of St. George-in-the- East). The map extract from the 1972 article below shows the location of the sites:

At the end of last week I was in Shoreditch High Street. To get to the next site, I turned into Bethnal Green Road and then into Sclater Street to look for:

Site 37 – Weaver’s House In Sclater Street. Now Derelict

Although the title for this site is singular, the map shows a run of buildings along the south side of Sclater Street adjacent to the railway lines. In the same location as in the original map are these buildings, which if they are the same, can still be given the description of derelict.

These houses once ran the length of Sclater Street and the 1972 map shows them continuing towards where I took the photo below. Apart from the derelict run of buildings that still remain, most were demolished to make way for a car park.

Sclater Street shows its age at the junction with Brick Lane where on the side of the building at the junction is the plaque shown in the following photo which reads “This is Sclater Street 1798”.

I then crossed over Brick Lane to get to Cheshire Street. A little way along Cheshire Street, I turned left into St. Matthews Row to find the next location:

Site 38 – George Dance’s St. Matthew’s And Watch House

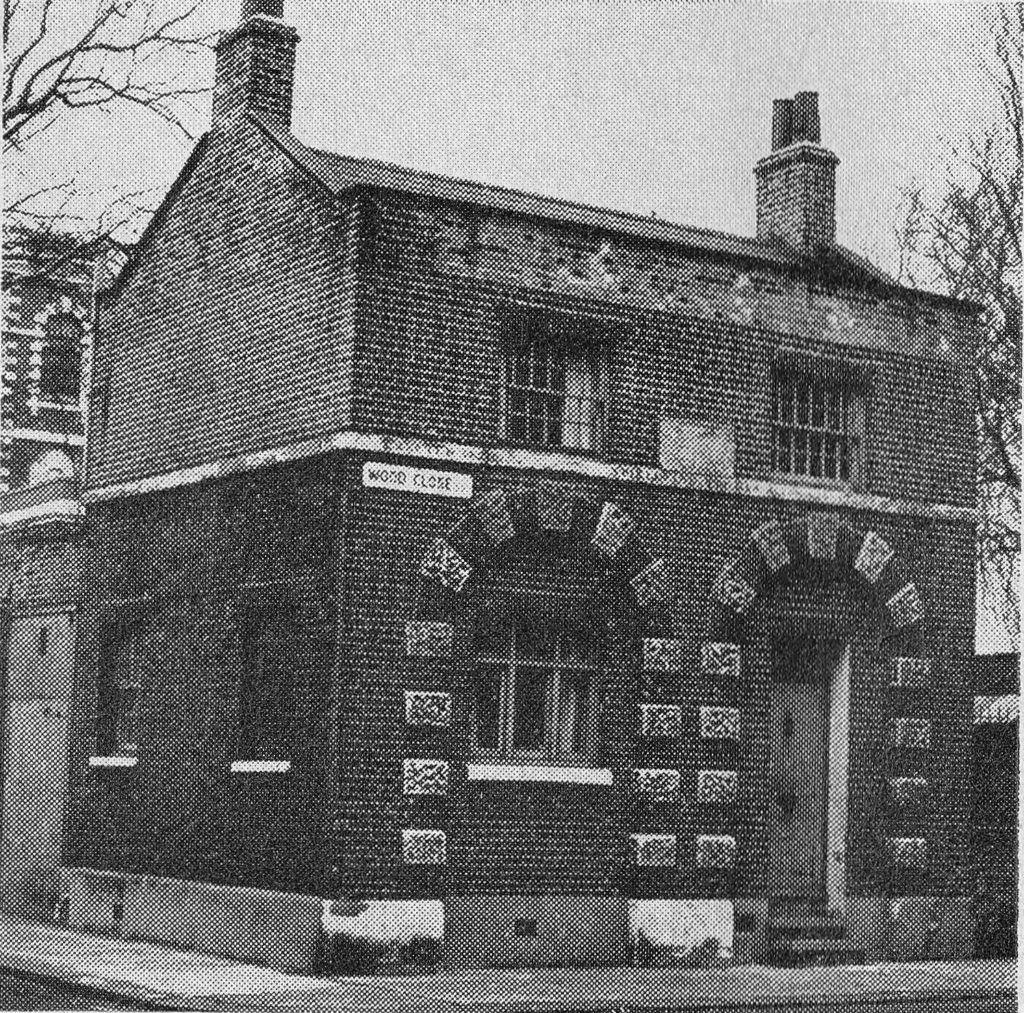

Walking towards the church of St. Matthew’s, I firstly found the Watch House on the corner of the churchyard:

Which looks almost the same as in the photo from the 1972 article:

According to the Architect’s Journal, the Watch House dates from 1820, however on the web site of the church there is an earlier date of 1754, which I suspect, is correct.The article explains why it was built “A watch-house stands at the corner of the churchyard. Body-snatching reached its peak during the 1820s and most London graveyards have, or had, watch-houses dating from that period. The Anatomy Act of 1832 put body-snatchers out of business. before that doctors could legally have only corpses of criminals for dissection.”

The church web site states that “by 1792 a person was paid 10s 6d per week to be on guard. A reward of 2 guineas was granted for the apprehension of any body snatchers.”

This is one of the finest examples of a watch house that I have seen.

A short distance past the watch house is the church of St. Matthew’s.

The original church was completed in 1746 to a design by George Dance. It was badly damaged by fire in 1859, reopening two years later. It was again badly damaged in 1940, with bombing reducing the church to a shell. It was not until 1961 that the church we see today was finally rebuilt and opened as recorded in this plaque in the foyer of the church.

The church has an association with some of Bethnal Green’s criminal past. Joseph Merceron was a churchwarden (see The Boss of Bethnal Green by Julian Woodford) and the funerals of Ronnie and Reggie Kray were all held at St. Matthew’s, the church being central to the area in which they grew up and commenced their criminal activities.

The interior of St. Matthew’s following the post war rebuild.

View of the rear of the watch house from the church yard.

The view of the church and churchyard from the rear of the watch house. Imagine being paid 10s 6d a week to watch over the churchyard overnight to stop any body snatchers.

Walking back down St. Matthew’s Row, the Carpenter’s Arms is on the corner with Cheshire Street. Once owned by the Kray’s, the pub now has a far more relaxed atmosphere.

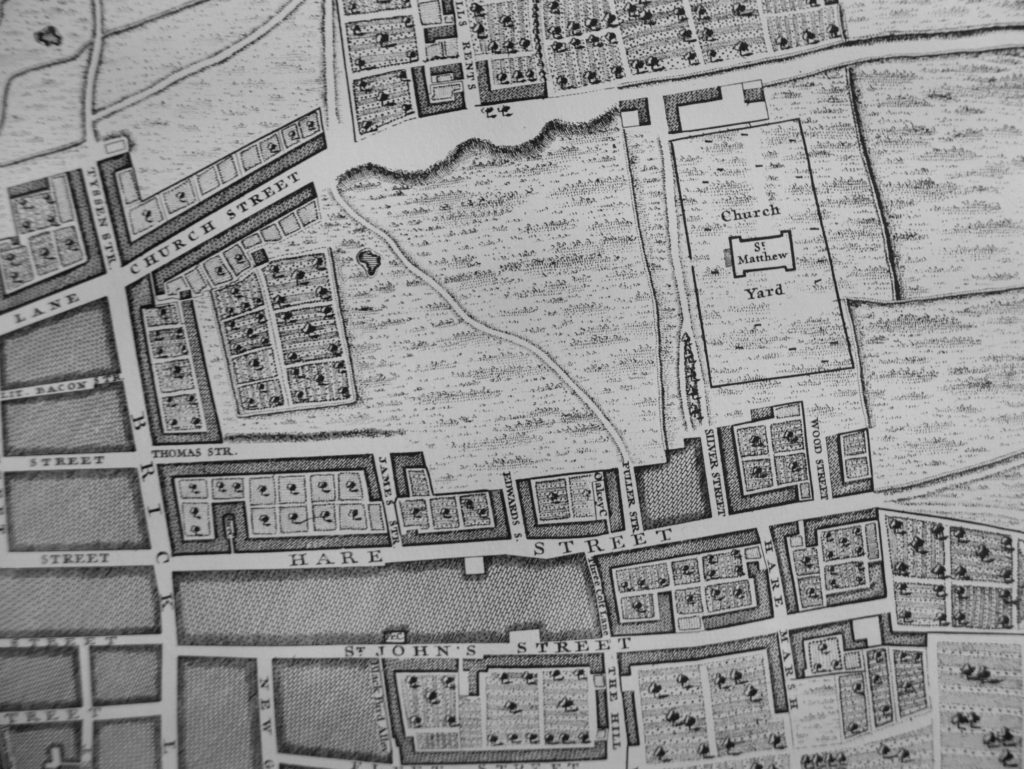

The area around Cheshire Street is fascinating. It was originally named Hare Street as can be seen in the following extract from John Rocque’s map of 1746. The name came from Hare Fields, the open space that was here before the development of the streets, the beginnings of which can be seen in the map. Leading south from Hare Street is a small street named Hare Marsh – the street is still in existence retaining its original name. The church of St. Matthew’s can be seen on the right with still large open spaces to east and west.

Cheshire Street is relatively quiet. Brick Lane seems to form a boundary between the busier streets to the west and the quieter streets to the east. In a few places Cheshire Street still retains the same feel as this area did when I first started walking here over thirty years ago.

In the following photo, an alley off Cheshire Street leads to a graffiti covered footbridge.

I was here for about 15 minutes and did not see a single person.

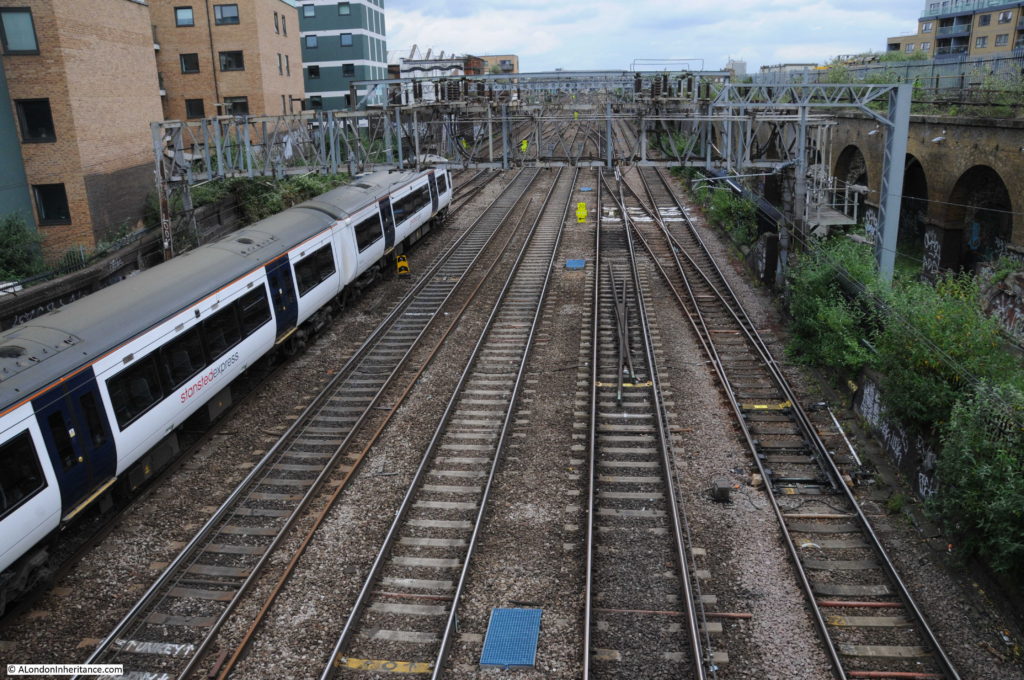

Peer carefully over the top of the bent metal spikes along the top of the metal panels along the edge of the bridge and there is a view of the rail lines into Liverpool Street station. Looking in the other direction and a Stanstead Express train heads from Liverpool Street towards the airport.

Looking in the other direction and a Stanstead Express train heads from Liverpool Street towards the airport.

The far end of the bridge.

Another turn off from Cheshire Street is Chilton Street and just along this street is St. Matthias Church House.

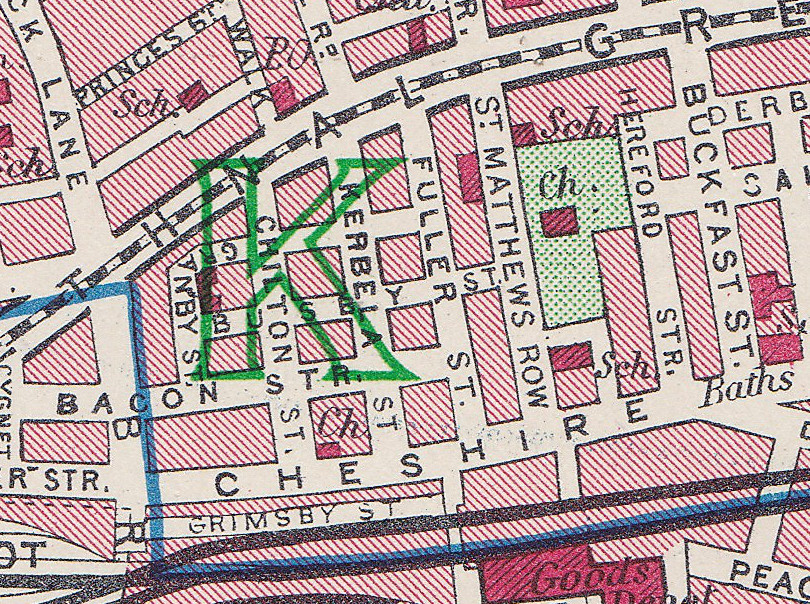

This was originally the parish rooms and hall for St. Matthias Church which was directly opposite as shown on the following extract from the 1895 Ordnance Survey map.

In the 1895 map above, Cheshire Street was still Hare Street, however by 1940 as shown in the following extract from the 1940 edition of Bartholomew’s Atlas of Great London, it had changed to Cheshire Street. No idea why or when the street changed name, but I prefer Hare Street as a reminder of the open fields that these streets have now covered. To the right of the church, crossing the Great Eastern Railway is a footbridge – the same (although of later construction) as the footbridge I walked across earlier.

The 1940 map also shows St. Matthias Church (the church marked above the first ‘E’ of Cheshire. I have not been able to confirm, however I suspect the church was damaged during the war and became one of the many churches that were not rebuilt.

Stone laid by Princess Christian on the 20th April 1887 on the front of St. Matthias Church House.

Entrance to Grimsby Street from Cheshire Street – another graffiti covered street running alongside the railway.

I walked the route of this and the previous post just before the 2017 General Election. This was the only election advertising that I saw.

Long terrace of Victorian buildings with shops running the length of the terrace along Cheshire Street coming back to the junction with Brick Lane.

FAX number of Bashir & Sons above their shop. It is the pre-April 1995 071 number. According to their web site they still use FAX, but the number now has the 0207 prefix. Cannot be many users of FAX in 2017 and I suspect it will become rare to see a phone number above a shop.

My next stop was in Whitechapel Road, so I walked south along the length of Brick Lane then turned east along Whitechapel Road to reach my next destination:

Site 39 – Mid To Late 18th Century Whitechapel Bell Foundry

It is somewhat ironic that a site that the Architects’ Journal was concerned about in 1972 survived the intervening 45 years, only to be at risk in 2017.

The bell foundry was established in Whitechapel in 1570 and has occupied the current premises since 1738, however production at the site ceased earlier this year. The announcement on the website of the bell foundry provides a number of reasons for the closure, including some that tell of the changes to the area, including “In recent years the area in which we are located has changed from commercial use to almost entirely residential use. New developments now in the process of being built adjacent to our site will give us neighbours who would find difficulties with our industrial output and noise.”

It is very noticeable how areas such as Whitechapel are changing from a mix of different industries, commercial business, retail and residential, to mainly residential developments. Whilst the shortage of housing within London is critical, districts turn rather bland and their local character is lost without a range of different activities.

The bell foundry seen from across Whitechapel Road.

The foundry buildings along Fieldgate Street:

Taking a break:

With the closure of the business at Whitechapel, I can only hope that the buildings will stay substantially as they are (Grade II listing should help) and that some form of industrial activity continues at the site.

Continuing along Feldgate Street, I turned into New Road to look for:

Site 40 – Late 18th Century Terraces

The 1972 map shows two rows of terraces either side of the junction of Fordham Street with New Road. The first row of terraces:

Within the terrace are two pairs of identical houses.

With some of the most cheerful keystones above the doorway that I have seen:

Opposite Fordham Street is Walden Street and although not mentioned in the Architects’ Journal, there is this lovely terrace of houses along one side of the street. There are so many architectural gems to be found walking around east London.

Walking back along New Road, these buildings are the next section, past the junction with Fordham Street marked on the Architects’ Journal map:

I imagine that the top floor is rather dark in this building:

Continuing along New Road:

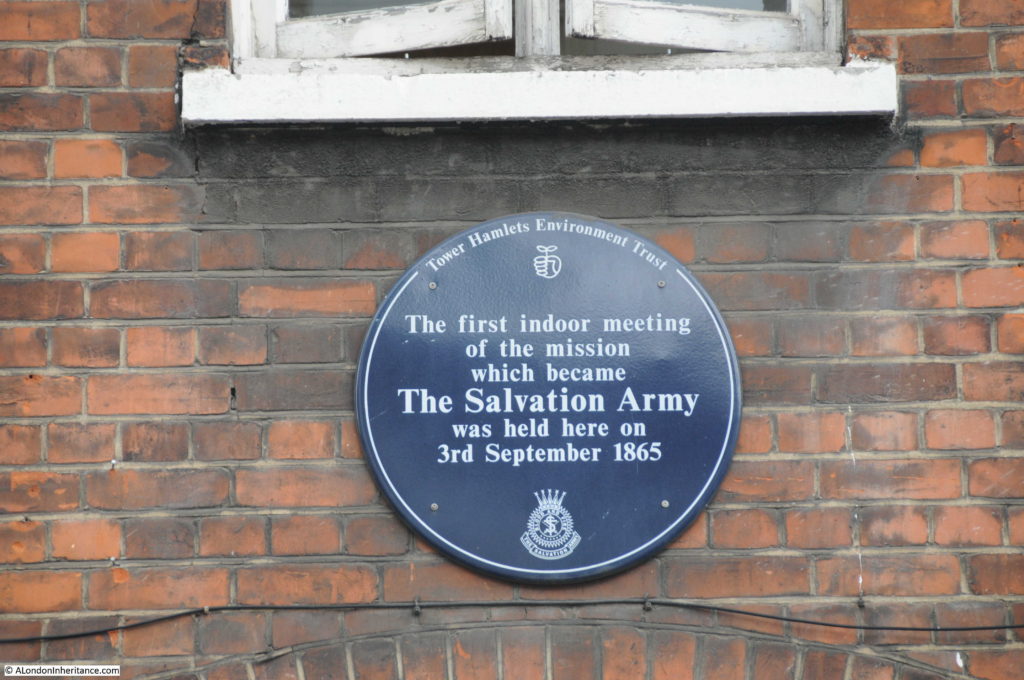

In the photo above, there is a red brick Victorian building on the right of the photo, taller than the others in the terrace. A plaque on the front of the building records a meeting held here in 1865:

To find the next location, I continued to the end of New Road, crossed over Commercial Road into Cannon Street Road, where a short distance along, opposite the junction with Burslem Street I found the next buildings.

Site 41 – Late 18th Century Group

The Architects’ Journal map, has a line marked along Cannon Street Road, directly opposite Burslem Street and here I found this lovely terrace of buildings.

It was interesting walking the length of Cannon Street Road as I did not notice any buildings with more than five floors, even the post war housing. Keeping buildings to a similar height along a street does help integrate very different architectural styles and materials.

A short distance along Cannon Street Road from the above photo is the junction with Cable Street. It is at this junction that John Williams, the alleged murderer in the Ratcliffe Highway murders was buried after he apparently committed suicide whilst awaiting trial.

The Ratcliffe Highway murders caused panic within this small area of east London in December 1811 following the brutal murder of two households. The investigation to find the murderer was somewhat chaotic and confused, but finally the trail seemed to lead to a seaman called John Williams. He apparently committed suicide whilst waiting trial, which was taken as admission of guilt and a show burial took place with his body paraded around the scenes of his crimes prior to being dumped into a pit dug at this junction.

The newspaper reports of the time provide a vivid account of his burial:

“INTERMENT OF JOHN WILLIAMS, On Monday, at midnight the body of this wretch was removed from the House of Correction, Coldbath Fields, to the watch-house near Ratcliffe Highway; and on Tuesday morning, at about ten o’clock, he was placed on a platform, erected six feet above a very high cart, drawn by one horse. The platform was composed of rough deals battened together, raised considerably at the head, which elevated the corpse. A board was fixed across the lower end, standing up about six inches, to prevent the body from slipping off. On this platform the body was laid; it had on a clean white shirt, quite open at the neck, and without a neck-handkerchief or hat, but the hair neatly combed, and the face clean washed. The countenance looked healthful and ruddy, but the hands and the lower part of the arms were of a deep purple, nearly black. The whole of the arms were exposed, the shirt being tucked quite up. The lower part of the body was covered with a pair of clean blue trowsers, and brown worsted stockings, without shoes. The feet were towards the horse, on the right leg was affixed the iron Williams had on when he was committed to prison. The fatal mall was placed uptight by the left side of his head, and the ripping chisel or crow-bar, about three feet long, on the other side. About 10 o’clock the procession, attended by the head constable and head boroughs of the district, on horseback, and about 250 or 300 constables and extra constables, most of them with drawn cutlasses, began to move and continued at a very slow pace.”

The article goes on to describe the route of the procession which passes the murder scenes until reaching the junction on the photo above, where:

“a large hole being prepared, the cart stopped. After a pause of about 10 minutes, the body was thrown into its infamous grave, amongst the acclamations of thousands of spectators. the stake which the law requires to be driven through the corpse had been placed in the procession under the head of Williams, by way of pillow, and after he was consigned to the earth, it was handed down from the platform, and with the maul was driven through the body. The grave was then filled with quick lime, and the spectators very quietly dispersed.”

A rather strange scene to imagination, standing at the junction today. The book “The Maul and the Pear Tree” by P.D. James and T.A. Critchely provides a fascinating account of the Ratcliffe Highway Murders along with alternative theories as to the real murderer.

Either side of the above scene is:

Site 42 – Late 18th Century Terrace And Shop Front

The map shows two markers for this site, one along Cable Street and the other along Cannon Street Road down towards The Highway.

This is the terrace along Cable Street:

This is a lovely terrace of houses along Cable Street from the junction with Cannon Street Road, until the entrance to St. George’s Gardens.

A little way along, the terrace is broken by the entrance to Hawksmoor Mews.

The blue plaque on the right is to Dr. Hannah Billig, a rather remarkable doctor who was born in Hanbury Street, Spitalfields in 1901 and moved to the above house from 1935 until 1964. The plaque records that she was known locally as “The Angel of Cable Street” and was honored with a George medal and MBE for her bravery in World War II and for Famine Relief Work in India.

At the end of the terrace, is the entrance to St. George’s Gardens. Alongside the entrance is the mural commemorating the Battle of Cable Street.

Work started in the mural in 1976, but it was not finally completed until 1983. Vandalism caused delays to the project, and this continued to take place after the mural was finished. My father took the following photo of the mural in 1986 showing a typical problem with white paint having been thrown at the mural.

The other marker on the map for this site was along the eastern side of Cannon Street Road between Brick Lane and The Highway, where a long terrace of houses, of slightly different design run along the street.

The other marker on the map for this site was along the eastern side of Cannon Street Road between Brick Lane and The Highway, where a long terrace of houses, of slightly different design run along the street.

Including this building at number 44 which is Grade II listed and built in 1810, so would have been here when John Williams was buried at the road junction. I have not been able to find out who was the “Thomas” named on the parapet, but it is the only building in the street with this type of decoration.

At the end of Cannon Street Road is the final site in this walk around east London:

Site 43 – Hawksmoor’s St. George-in-the-East And Rectory

St. George-in-the-East was one of the 50 churches planned for London under the New Churches in London and Westminster Act of 1710. Only twelve were built of which St. George was one.

Work started on the church in 1714 and the church was consecrated in 1729, providing a new church for the rapidly expanding population of east London.

Although east London’s population was expanding rapidly, it was mainly running along the river, south of the Ratcliffe Highway, north of this road it was still relatively rural. The extract below from John Rocque’s map of 1746 shows the new church in the lower left with the Ratcliff Highway running below the church from west to east. North of the church is Bluegate Field (now Cable Street) and it is rather tempting to imagine that where a track is shown running diagonally across the fields, there was a blue gate between the track and the road.

The rectory referred to in the Architects’ Journal listing for the site is shown by the black rectangle in front and to the left of the church in the 1746 map above. The rectory building is still there:

The church suffered considerable damage during the war and was gutted by an incendiary bomb in May 1941 with only the external walls and tower still standing. The church was rebuilt after the war and rededicated in 1964. The rebuilding though was rather unusual.

Rather than rebuild the church to the same original Hawksmoor design. the external walls and tower were left standing and a new church building was constructed within the interior, therefore when you walk through the main entrance under the tower expecting to walk into the church, there is an open space, open to the sky with the post war church building to the rear of the original church.

A rather clever use of space as the original church was probably far too large for post war congregations and the new building provides a more intimate space. This was achieved whilst also preserving the external walls and tower so that externally the church still appears as when originally built.

The view from across The Highway:

Within the churchyard is an old mortuary building. This was converted into a Nature Study Museum in 1904 with the aim of providing local people with more contact with the natural world. The museum included live fish, stuffed birds and mammals and displays of butterflies. The information plaque in front of the building records that during the summer months up to 1,000 people, mostly local school children, would visit the museum each day. It was closed during the war, did not reopen and has since fallen into the state of disrepair that we see today.

This last site concludes my walk to find (along with last week’s post) the sites in category B between Shoreditch and St. George-in-the-East.

It has been a brief walk, there is so much more to write about this area of east London, but I did achieve my aim of checking to see if the sites of concern in 1972 have survived, and it is good to see that the majority are still here, and looking in good condition.

The Whitechapel Bell Foundry is a reminder that these buildings, along with so many other historical buildings across London, will always be at risk from the constant threat of demolition, or an unsympathetic development.

The Architects’ Journal wrote about these sites in 1972, 45 years ago. It will be interesting to take the same walk in 2062.