Last Saturday was a windy, sunny spring day in London, so what better than to spend an hour exploring the cemetery of St John at Hampstead.

The reason for this specific cemetery was to find a rather unusual grave that my father had photographed in 1949. This is the grave of George du Maurier.

The same view 70 years later in 2019:

The grave today does not appear as well looked after as in 1949. There was some space surrounding the grave in 1949, however today there are many more graves alongside. The tree on the left has been cut down and today only the stump survives. One of the significant differences which I find in many of my father’s photos is the number of cars in the street. In 1949 streets were generally free of parked cars, in 2019 there are very few streets without parked cars, or lots of passing traffic.

George du Maurier, or to give him his full name, George Louis Palmella Busson du Maurier, was born in Paris on the 6th March 1834 and died on the 8th October 1896.

His grandparents on his father’s side were French and according to an 1886 newspaper account, emigrated to England during the “Reign of Terror” during the French Revolution. Later accounts state that his grandfather was a glassblower and left France to avoid fraud charges, adding the du Maurier name to give the impression of a French aristocratic background.

His father returned to Paris and it was there that George was born. He spent much of his childhood in France until the family returned to London and George started as a student at the Birkbeck Laboratory of Chemistry.

The Hampstead and Highgate Express on the 24th July 1886, in their series on well known residents features George du Maurier and explains that whilst his father wanted him to become a chemist, including going to the expense of setting up his own private laboratory, George was more interested in the arts and “humorous draughtsmanship“.

After the death of his father, he gave up chemistry and went to Paris to study art. He later returned to London, after spending an additional three years in Germany and Belgium and started in his career as a draughtsman, producing drawings for publications. Punch was the publication that became most associated with his work, and he produced drawings for Punch for twenty five years.

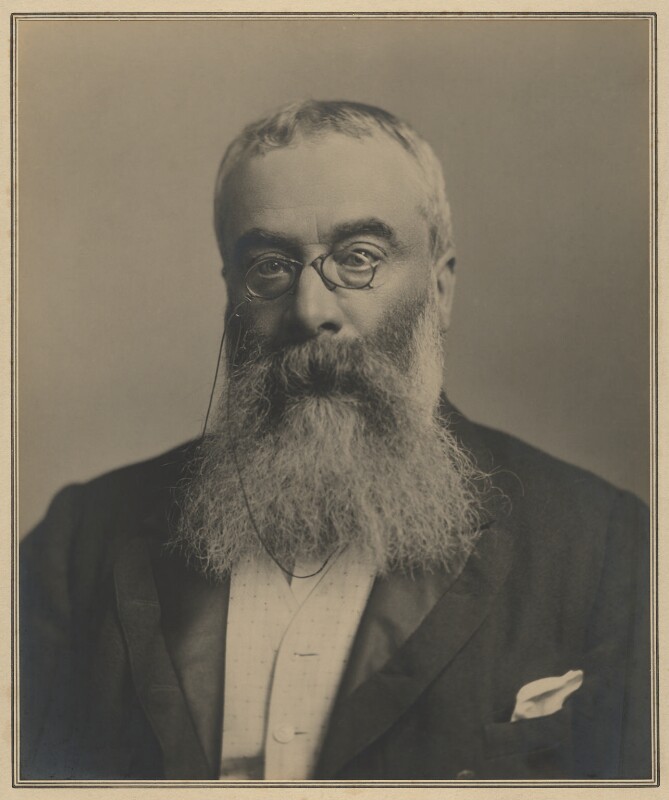

George du Maurier photographed in 1889 (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

The article in the Hampstead and Highgate Express described his work: “Over a period of nearly twenty five years he has contributed to ‘Punch’ an almost endless series of drawings illustrative of the manners and customs of English society. Some of its phenomena, the shams, affectations, meannesses and frivolities peculiar to its salons and garden parties, and some other scenes of fashionable life, are treated by the artist with the most biting satire. But a great deal belonging to English life and society, especially its venial weaknesses, is treated by the artist from the humorists’ standpoint, namely that of light satire and good humour. In an appreciation of beauty and grace as seen in his numerous presentments of women and children, and in his general design of his pictures, Mr du Maurier excels all preceding English pictorial humourists. In the ‘Punch’ contributions he has not only shown power as a graceful and refined artist, but in his drawings for that amusing periodical there are touches of wit, humour, satire, subtle observation, and poetic suggestiveness which are indisputably the work of a man of genius.”

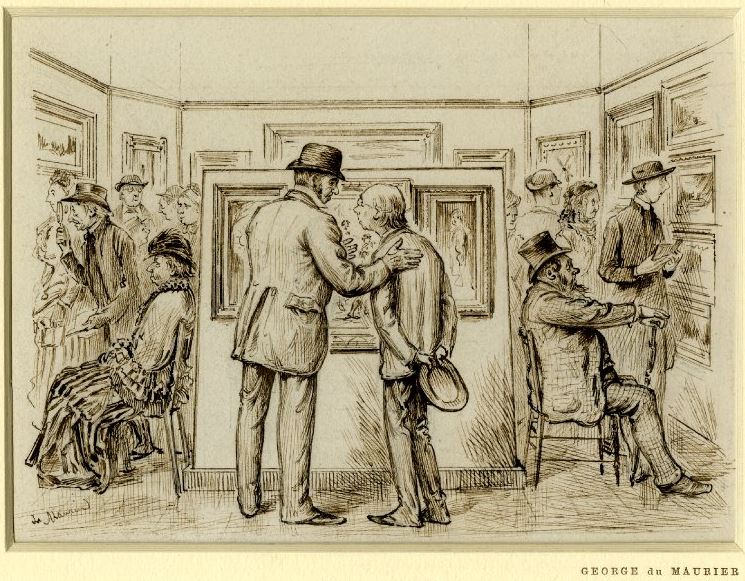

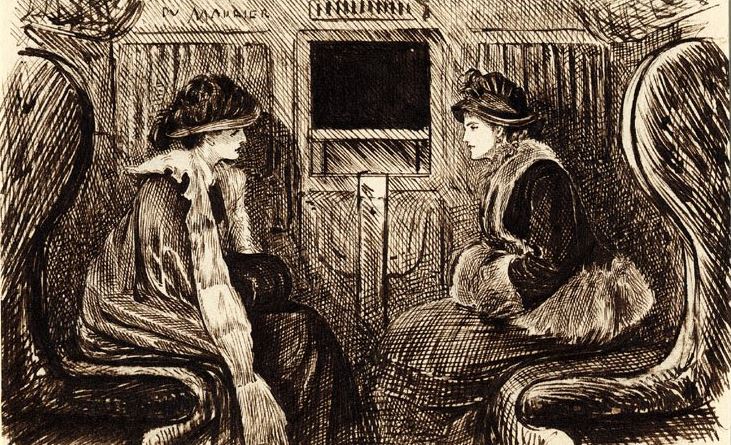

A couple of examples of George du Maurier’s work for Punch are shown below (both ©Trustees of the British Museum).

The following drawing is an illustration for Punch, dated the 18 October 1880. It is described as “What our Artist has to put up with, a man talking and touching the shoulder of another, both standing before a group of three pictures, other figures examining other pictures on the surrounding walls”.

The following drawing is dated the 12th January 1878 and is a study of two female figures sitting in a carriage on the Metropolitan Railway.

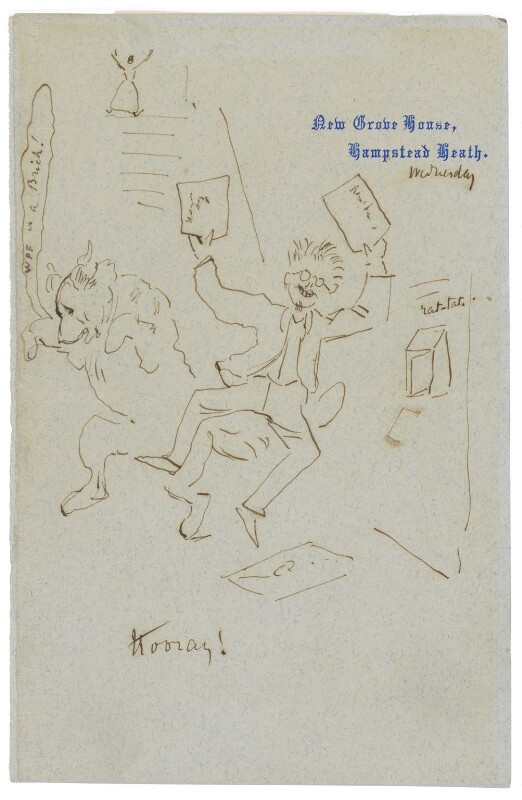

He also produced numerous sketches for his own amusement, including many self portraits. This one on paper, stamped with his home address in Hampstead shows George du Maurier exclaiming ‘Hooray!’ at the arrival of the post with his dog dancing nearby.

George du Maurier married Emma Wightwick, who he had met whilst in Germany. They had five children. One of his children was the actor Sir Gerald du Maurier, who was the father of the authors Daphne du Maurier and Angela du Maurier.

In his later years, George du Maurier turned to writing and produced three novels between 1889 and 1897- Peter Ibbetson, Trilby, and The Martian. Trilby was a significant best seller with the Victorian story of a fallen woman with a good heart.

George du Maurier was 62 when he died of heart failure. He had lived at two locations in Hampstead during his life, but had moved around a number of times and at the time of his death was living at Oxford Square, near Hyde Park.

His funeral at St John at Hampstead was a significant event, attended by many dignitaries of the day, authors and the staff of Punch magazine.

The memorial at his grave is unusual, and I cannot find any references as to why the design was chosen.

I am also unsure why my father chose to photograph du Maurier’s grave given the number of famous names buried at St John at Hampstead. My father was also a draughtsman, professionally for the St. Pancras Borough Council Electricity and Public Lighting Department, then the London Electricity Board, but also was interested in drawing many other subjects and it may have been this interest in an earlier draughtsman that prompted the choice of grave to visit and photograph.

George du Maurier’s grave is in the “Additional Burial Ground” just across the road from the church of St John at Hampstead and the original graveyard. The extension opened in 1812. This is the view of the additional burial ground from Church Row. The church is on the left, just behind the car. George du Maurier’s grave is up against the railings, just behind the poster.

Another view of George du Maurier’s grave. Underneath the name and dates of birth and death is written “A little trust that when we die, we reap our sowing and so – good bye“.

The monument above the grave is to Geoirge du Maurier, however there are panels inset to the front and sides that record the children of George and Emma du Maurier.

Here, their eldest son, Lieutenant Colonel Guy Louis Busson du Maurier is recorded as being killed in action on March 10th 1915 at Alston House, near Kemmel in Flanders.

Marie Louise Busson du Maurier, their youngest daughter.

Gerald Hubert Edward Busson du Maurier, their youngest son.

There are numerous fascinating graves in the cemetery of St John at Hampstead. Walking around is a history lesson of the past couple of centuries.

The following grave and monument was not there when my father took the photo at the top of this post. It is immediately to the left (when looking from the road) of George du Maurier’s grave and is the grave of Hugh Gaitskell, the leader of the Labour Party from 1955 to 1963, along with his wife, Dora.

Adjacent to the grave of Hugh Gaitskell are plaques to the Hampstead resident, comedian and satirist Peter Cook and his wife Lin.

Strangely Wikipedia states that Peter Cook’s ashes were buried in an unmarked grave so either the plaques are in the wrong place, or Wikipedia is wrong. – I suspect the later.

There was one specific grave that I was interested to find, and after some searching I found the grave of Sir Walter Besant.

Sir Walter Besant was born in Portsmouth in 1836 and died in Hampstead in 1901. His life almost matching the reign of Queen Victoria.

He was a prolific author of both novels and factual books. Two of his more famous novels, “Children of Gibeon” and “All Sorts and Conditions of Men” dealt with the living and social conditions of east London and the relationship between east and west London. The later book helped with the establishment of the People’s Palace in east London by John Beaumont. The book included the planning and build of a Palace of Delight to provide education, concerts, picture galleries, reading rooms etc. free to the people of east London. The name used in the book was part taken by the People’s Palace, and the book brought funding and support to the People’s Palace.

For many of his books, he worked with the author James Rice and the two men went walking across London to gather background for their books. James Rice died in 1882 and in the preface to “All Sorts and Conditions of Men”, Besant wrote: “The many wanderings, therefore, which I undertook last summer in Stepney, Whitechapel, Poplar, St. George’s-in-the-East, Limehouse, Bow, Stratford, Shadwell and all that great and marvelous unknown country we call East London, were undertaken, for the first time for ten years, alone. They would have been undertaken in great sadness had one foreseen the end. In one of these wanderings I had the happiness to discover Rotherhithe, which I afterwards explored with carefulness; in another, I lit upon a certain Haven of Rest for aged sea captains, among whom I found Captain Sorensen; in others I found many wonderful things, and conversed with many wonderful people”.

I suspect that during the 19th century there were quite a few authors wandering the streets of east London.

In a review of one of Besant’s book, the London Evening Standard wrote in 1901 a paragraph that is just as true today:

“It is commonly said that half the world is ignorant of how the other half lives. That is more than true of London, for its vastness limits the social outlook of its inhabitants to the narrow groove of their daily work. How little do most people know of the occupations, or even names, of their immediate neighbours. Sir Walter Besant however is well acquainted with the region he is describing and his details are always equally graphic and correct.”

Sir Walter Besant spent six years abroad when he was a Senior Professor of Mathematics at the Royal College in Mauritius. He was Secretary of the Palestine Exploration Fund. Besant was also instrumental in the founding of the Society of Authors and became the first Chair of the society. During his time with the society he was active in furthering the cause of copyright for an author’s work.

Sir Walter Besant, looking very Victorian in 1896 (photo © National Portrait Gallery, London)

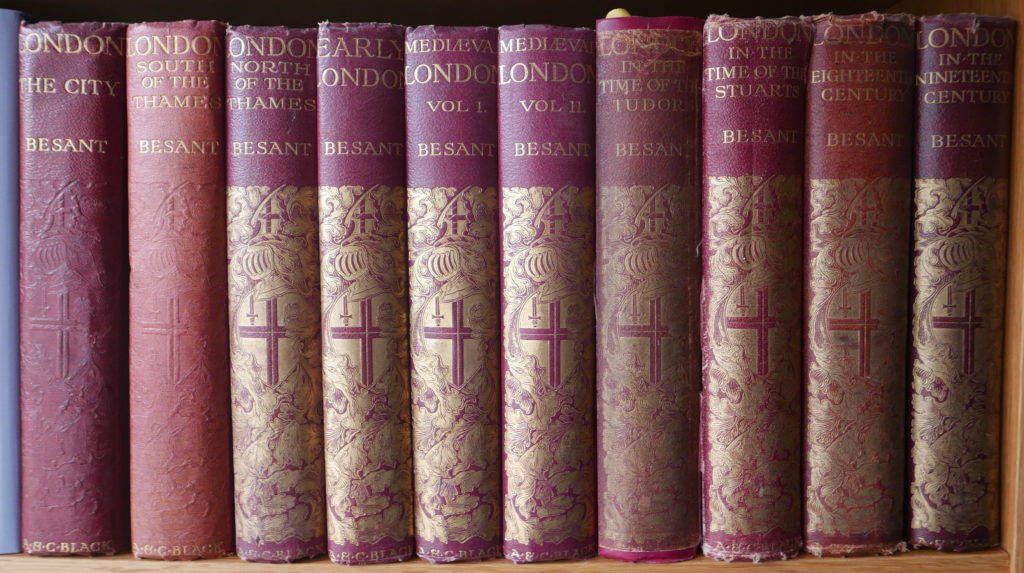

The reason why I wanted to find Besant’s grave was that I have many of his historical and topographical books on London. They are comprehensive studies of a specific period in time and of a region of the city. Full of early photos, drawings and maps. This is my copy of Besant’s London books published by A&C Black.

The London Evening Standard on the 11th June 1901 carried a comprehensive obituary of Besant.

It records that “When the People’s Palace was opened by Queen Victoria, the obligation which London and the nation owed to Mr. Besant was publicly recognised, and in 1895 the honour of Knighthood was bestowed upon him, amid universal approval.”

He was married to Mary Foster-Barham, and the obituary illustrates how male and female children were treated differently. The obituary records that when he died, his two sons, Philip and Geoffrey were both at the Front (South Africa). The former being a Captain in the 4th Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment, the latter a trooper in the Imperial Yeomanry. Of his daughters, the only mention is that one unnamed daughter was with Walter Besant at the time of his death.

It was fascinating to find the grave of an author that has provided me with a Victorian view of the history of London.

It was a pleasure to walk round and explore the “Additional Burial Ground” of St John at Hampstead on a sunny spring day.

The cemetery is at the exactly right place between being wild and too manicured. Last autumn’s leaves still cover the ground, moss covers many of the graves and narrow paths provide walkways across the cemetery. The houses of Hampstead close in on the cemetery boundaries.

This stunning Magnolia tree will look magnificent in a couple of weeks (providing the flowers have not been blown away with the recent gales).

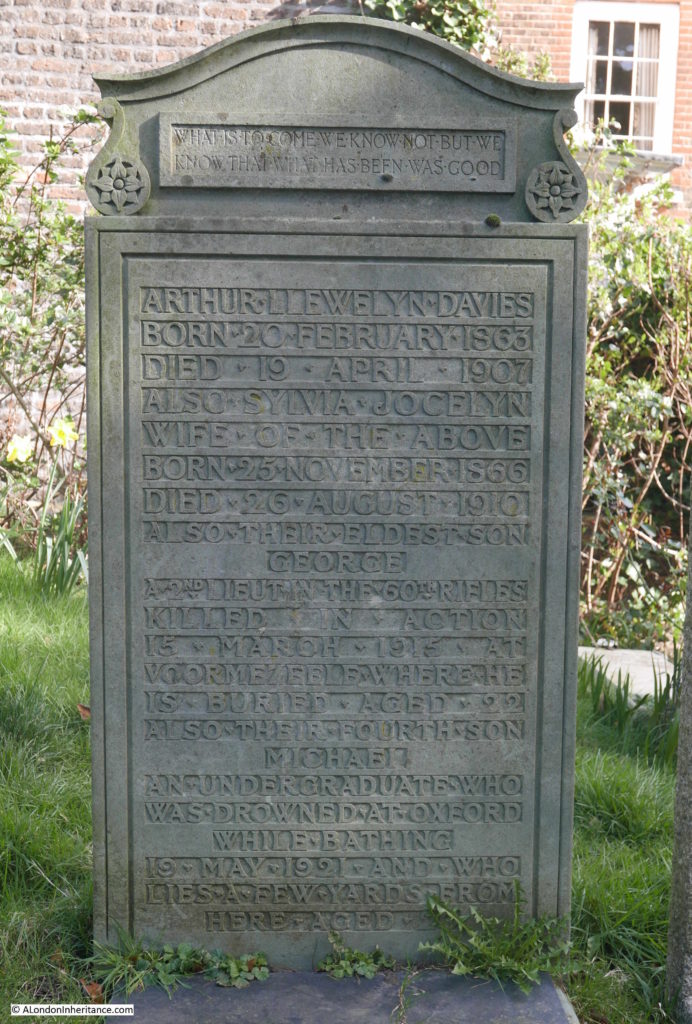

There are so many graves that tell an interesting and often tragic story of 19th and early 20th century life. This is the grave of Arthur Llewelyn Davies who died in 1907 and his wife Sylvia Jocelyn who both died at the same age of 44 (although in different years).

Perhaps the only good thing about their relatively young deaths is that they would not have to suffer the deaths of their eldest son George who was killed in action at the age of 22 on the 15th March 1915, and the death of their fourth son Michael who drowned whilst bathing at Oxford where he was an undergraduate at the age of 20.

Inscriptions also record how individuals (or their families) wanted to be remembered. This is the grave of George Atherton Aitken – The Very Mirror Of A Pubic Servant.

After visiting the additional cemetery, I walked across the road to visit the church of St John at Hampstead and the original cemetery.

References to a chapel on the site date back to the 14th century. The core of the current church was consecrated in 1747 with the spire being added in the 1780s. The church was expanded during the middle of the 19th century to support the growing population of Hampstead. During the rest of the 19th century there would be improvements (such as gas lighting), decoration and minor changes. The church was given a lighter colour decoration in 1958 to replace the dark Victorian interior.

The interior of St John at Hampstead today:

The original cemetery around the church has a number of fascinating graves of those who have made their mark over the centuries.

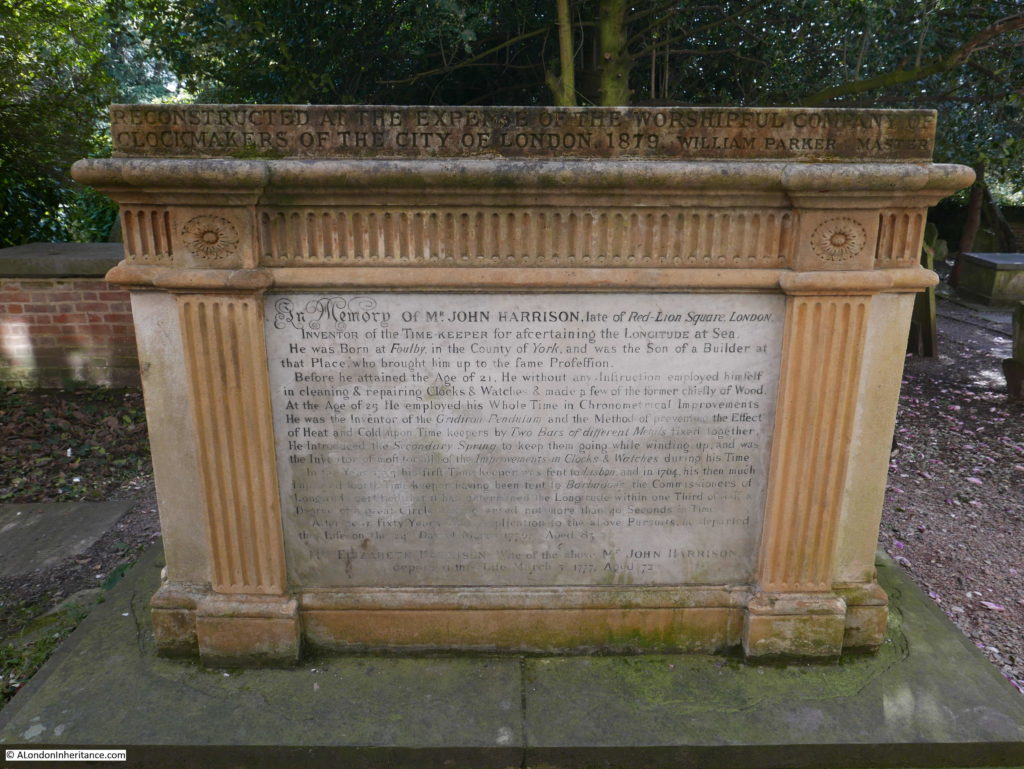

Close to the church is the grave of John Harrison.

The inscription provides a summary of Harrison’s work;

“In memory of Mr John Harrison , late of Red Lion Square, London. Inventor of the Time-Keeper for ascertaining the Longitude at Sea.

He was born at Foulby, in the County of York, and was the Son of a Builder at that Place, who brought him up to the same profession.

Before he attained the Age of 21, he without any Instruction employed himself in cleaning and repairing Clocks and Watches and made a few of the former chiefly of Wood. At the age of 25 he employed he Whole Time in Chronological Improvements. He was the Inventor of the Gridiron Pendulum and the Method of preventing the Effect of Heat and Cold upon Time keepers by Two Bars of different Metals fixed together. He introduced the Secondary Spring to keep them going while winding up and was the Inventor of most (or all) of the Improvements in Clocks and Watches during his Time.

In the year 1735 his first Time keeper was sent to Lisbon, and in 1764 his then much Improved fourth Time keeper, having been sent to Barbados the Commissioners of Longitude certified that it had determined the Longitude within one Third of Half a Degree of a Great Circle having erred not more than 40 Seconds in Time.

After near Sixty years close Application to the above Pursuits, he departed this Life on the 24th Day of March 1776, Aged 83.

Mrs Elizabeth Harrison Wife of the above Mr John Harrison departed this life March 5th 1777, Aged 72.”

Despite the success of the trial with the fourth time keeper (model H4), Harrison had problems with the Board of Longitude which had been set up to oversee the trials and a financial award for the accurate measurement of Longitude under the Longitude Act. The Commissioners on the Board of Longitude did not feel that sufficient trials had been carried out, and they initially offered part of the award (£10,000) with a further £10,000 if Harrison’s time keeper could be replicated by other manufacturers. This would have required the design details of Harrison’s time keeper to be published freely for other manufacturers to use.

Harrison did eventually get a substantial financial award from Parliament, with the support of the King.

The grave of an artistic Hampstead resident can be found up against the boundary wall of the cemetery. This is the grave of the artist John Constable.

Constable was a frequent visitor to Hampstead and lived for many years in the area, including in a house in Well Walk between the years 1827 until 1834. It was from the drawing room of the house in Well Walk that he painted a number of views across to the centre of the City.

An example being the following view with St. Paul’s Cathedral in the centre distance. An inscription on the rear of the painting reads: “Hampstead. Drawing Room 12 o’clock noon Sept.1830” (Image ©Trustees of the British Museum)

The hilly nature of Hampstead is visible in the graveyard, as the land descends from the high point of 135m at Whitestone Pond down towards the River Thames.

The graveyard is also managed in such a way that whilst it is not too wild, it is not manicured and a plaque at the entrance provides information on the range of wildlife that can be found.

Towards the south east corner of the graveyard, just across Frognal Way, there is a rather large construction site.

I believe this was 22 Frognal Way, which was occupied by a modernist house built to the design of Kentish Town architect Philip Pank. The house was commissioned by Harold Cooper and built in 1978. Cooper was the founder of the Lee Cooper jeans brand. After his death in 2008, the house became derelict and although there were attempts to get the house listed and restored, planning permission appears to have been given for demolition and construction of a new house.

The new building will be low profile consisting of a single story as viewed from street level, however as can be seen by the size of the excavation in the above photo, the new building will have considerable basement space.

Some of these building sites where basements are constructed for residential homes appear more like a Crossrail construction site. I suspect I know what the neighbours think about having such a large excavation on their doorstep.

The church of St John at Hampstead, the original and additional graveyards, are a fascinating place to explore, and if you have a couple of hours spare on a sunny day, there is no better place to learn about the residents of this area of north London.