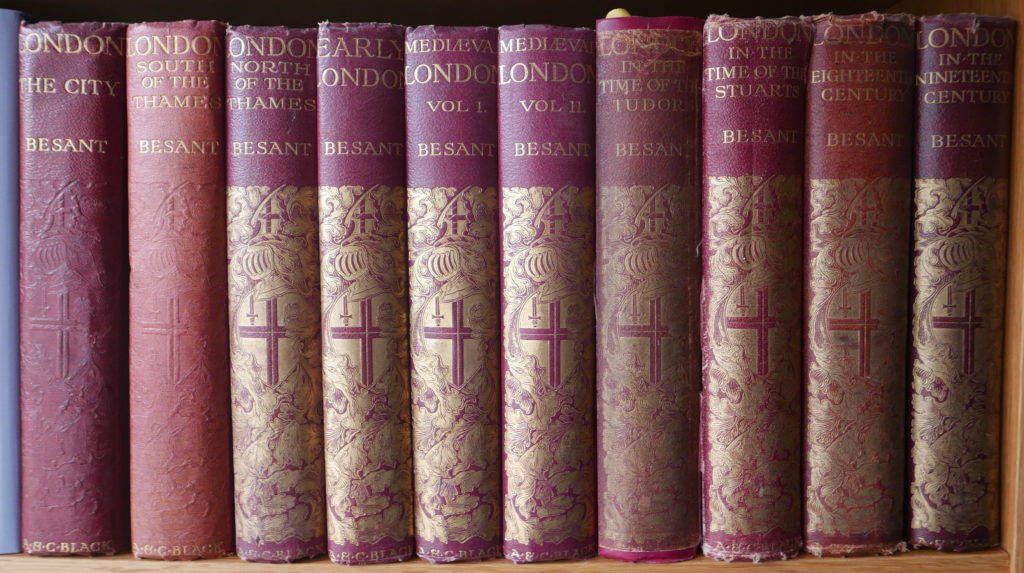

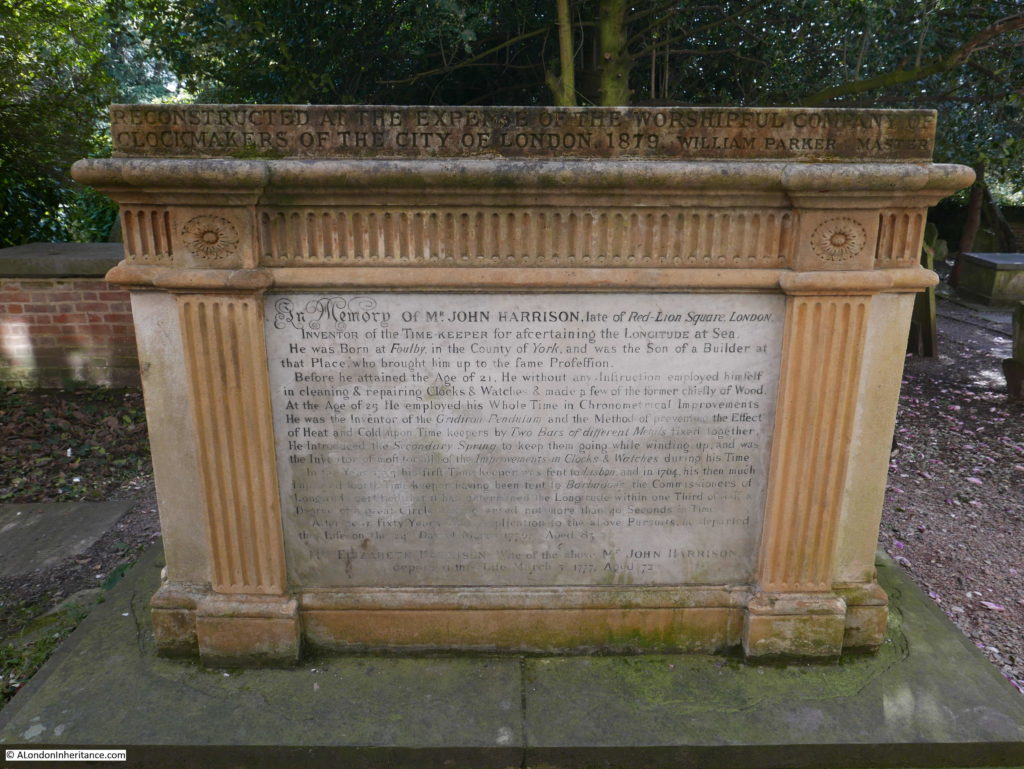

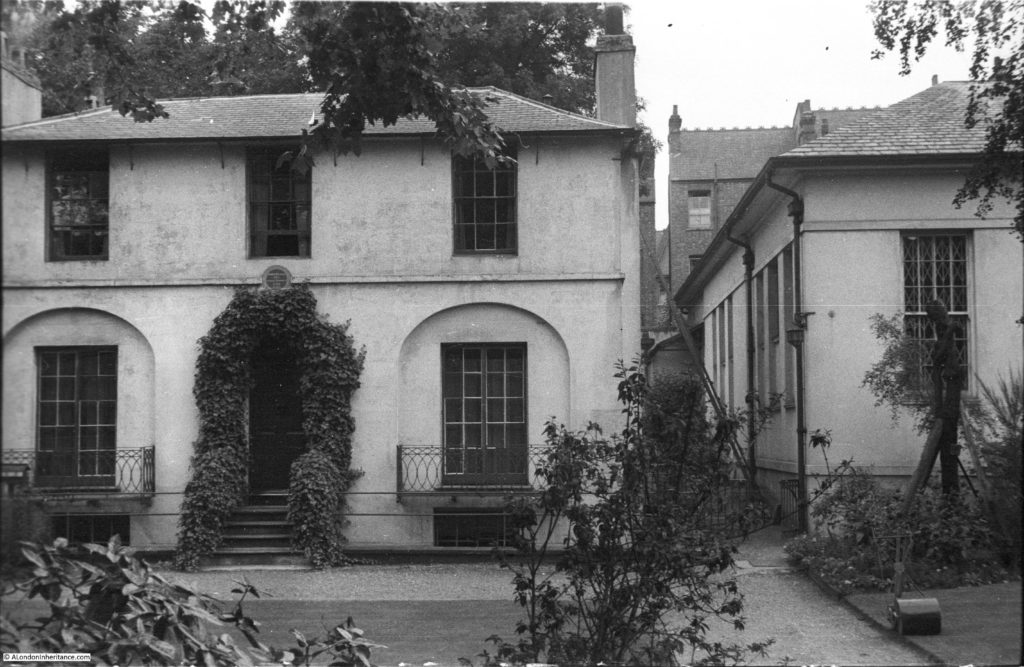

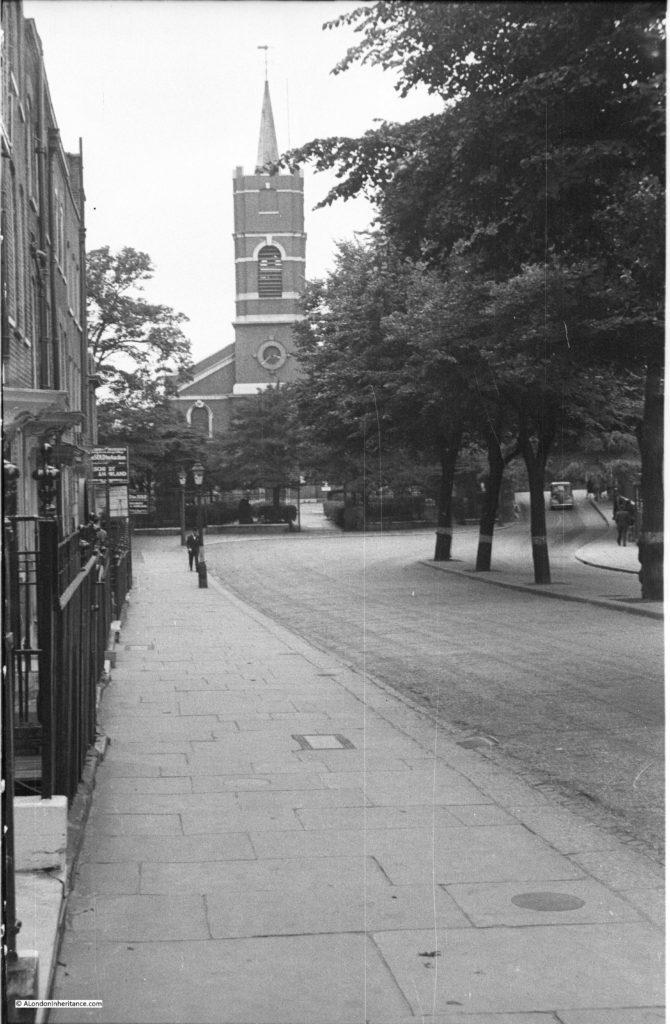

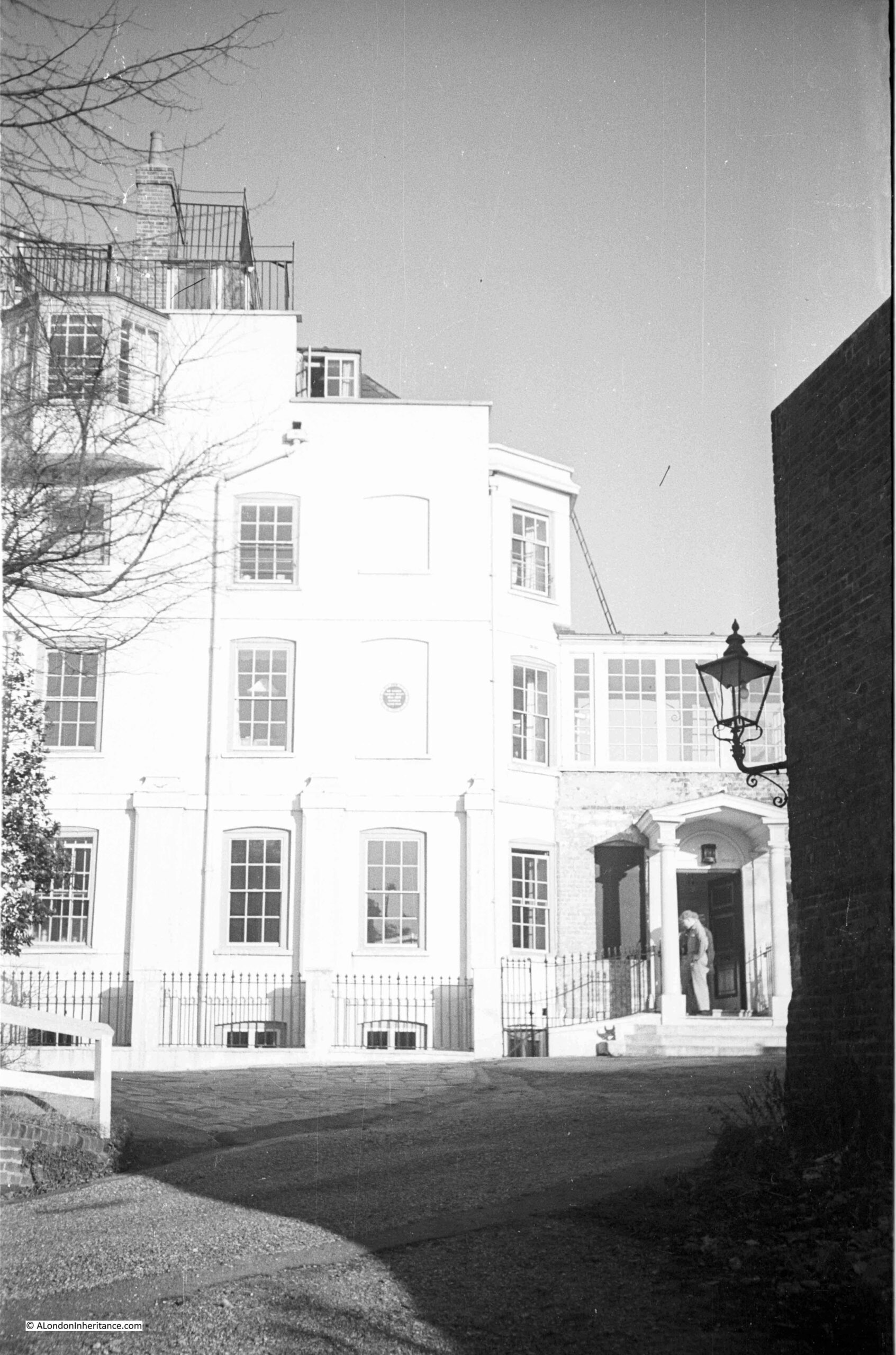

In last Sunday’s post, I complained about the lack of sunlight when I was taking photos of Peckham. The day that post was published was a glorious February day, bright sunlight and clear blue sky, so I took the opportunity for a walk around Hampstead, starting with Admiral’s House, the location of one of my father’s photos from 1951.

The same view in February 2023:

The view of Admiral’s House is much the same, however if you look to the right of my father’s photo, there is a brick wall and a rather nice lamp. These are not visible in my photo.

The reason being that both photos were taken a few feet along a walkway that follows the brick wall on the right. In the 72 years between the two photos, a large amount of small trees and bushes have grown up alongside the wall, so I could not get into the exact same position as my father when he took the 1951 photo:

The lamp on the end of the wall is still there, it looks the same design, so I assume it is the same lamp, however there are some shiny washers and bolts now holding the mount to the wall, so these have been replaced:

Admiral’s House is a short walk from Hampstead Underground Station. North along Hampstead Grove, then turn left into Admiral’s Walk, where there is a large sign on the corner, helpfully pointing to Admiral’s House:

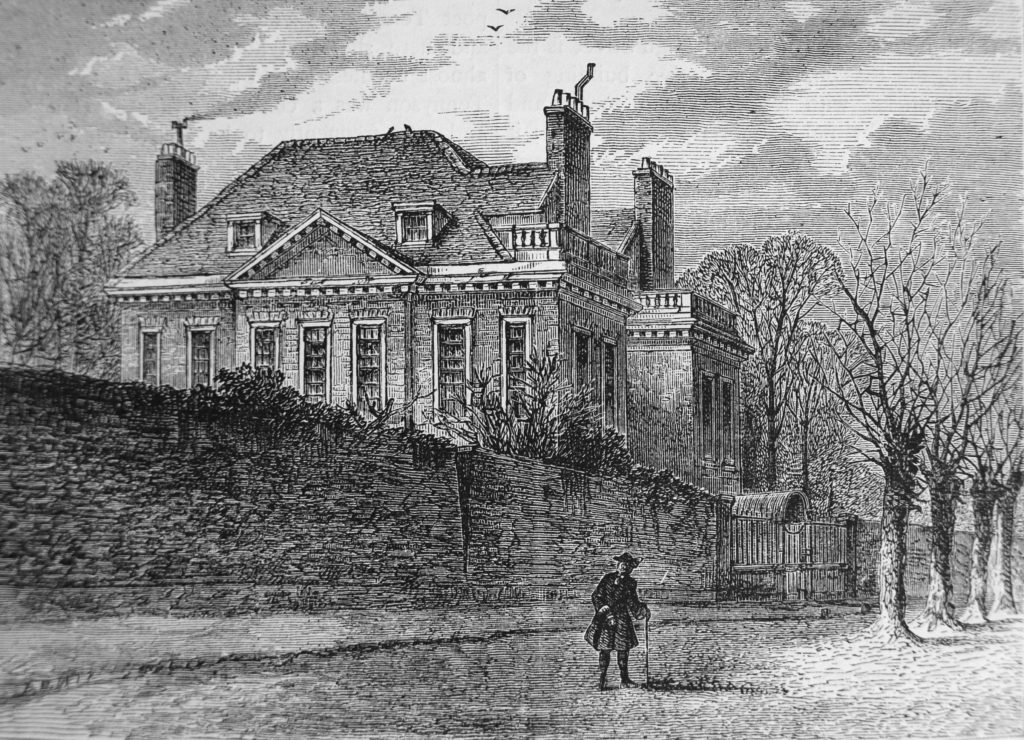

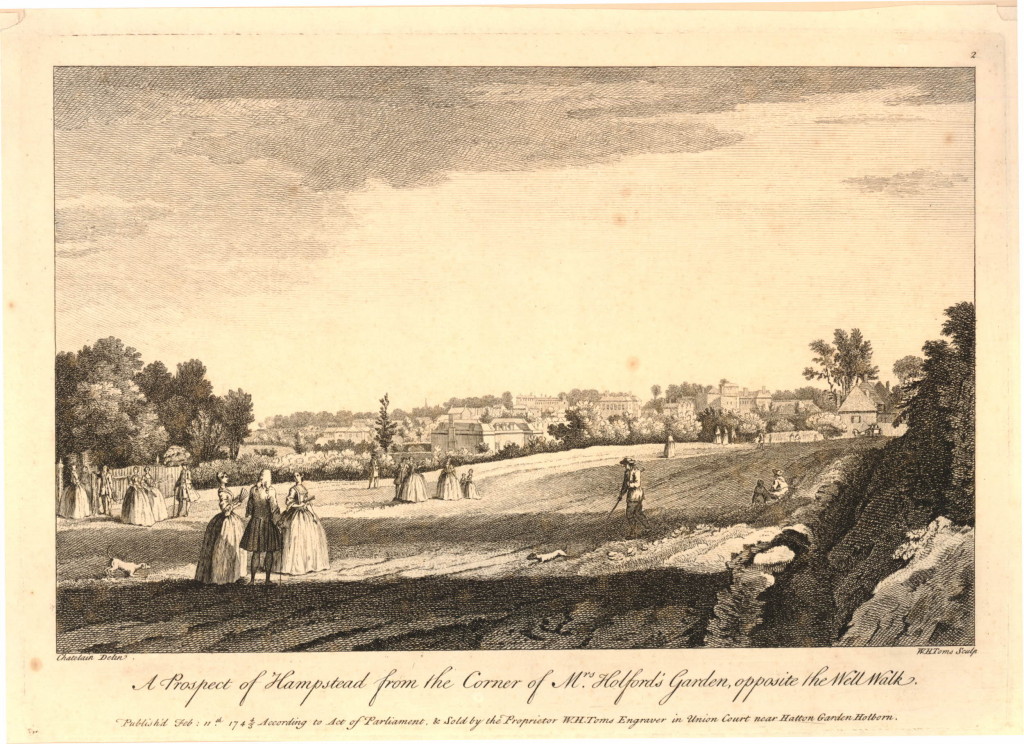

The house appears to date from the early 18th century, when it was built for a Mr. Charles Keys. At that time, the building was known as the Golden Spike, after the Masonic Lodge that met in the building between 1730 and 1745.

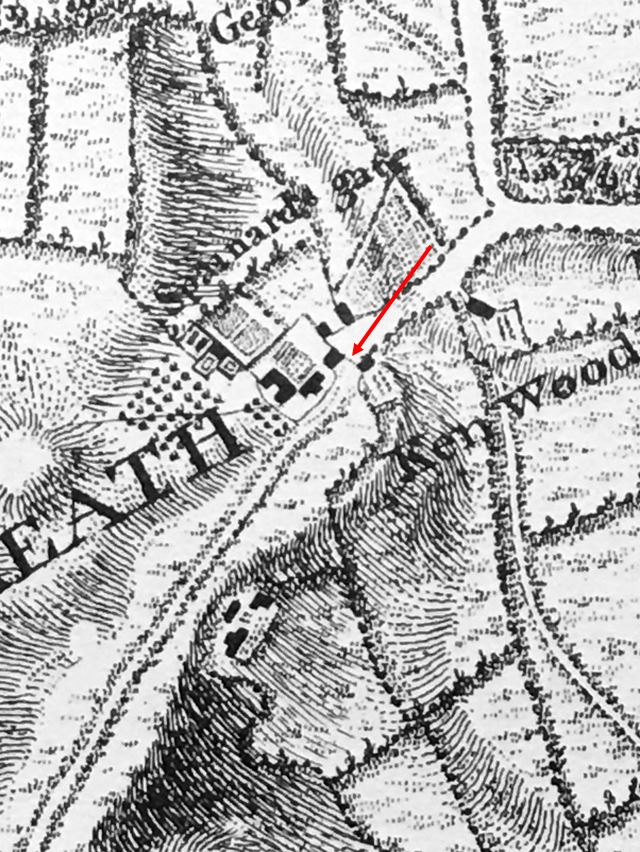

Admiral’s House can be seen in Rocque’s 1746 map, shown circled in red in the following extract, where, for reference, I have also circled Fenton House in blue, with the distinctive squared shape of its garden between Fenton and Admiral’s Houses.

From 1775 to 1810 the house was occupied by Fountain North, apparently a former naval captain. North changed the name of the house to ‘The Grove’.

Fountain North is a rather unusual name, and I did find some basic information about him. He died on the 21st of Spetember, 1810 in Hastings. The brief line recording his death in newspapers at the time states that he was of Rougham Hall in Norfolk. There is no mention of Hampstead. I could only connect this record with the Fountain North who lived in Hampstead, when I found the report of the death of his wife, Arabella North, who died in Weymouth in 1832, and the record states that she was “the widow of Fountain North, of Rougham Norfolk, and Hampstead, Middlesex”.

It was Fountain North who constructed the quarter deck on the roof of the house, and it was from here that he apparently fired a cannon to celebrate naval victories, however I cannot find any references to this from the time, so difficult to say whether or not it is true.

This is where there has been confusion with an Admiral Barton, a genuine Admiral who lived between 1715 and 1795, who has been alleged to have built Admiral’s House, but in reality had nothing to do with the house in Hampstead.

Even publications such at the Tatler recorded Admiral Barton as being responsible for the house, for example, in an article on the 14th July, 1940 on Pamela Lady Glenconner, who was then living in the house with her family, the Tatler reported that “Admiral’s House was built in the eighteenth century by Admiral Barton who, after an adventurous career which included shipwreck on the Barbary Coast, being sold into slavery, rescue and court martial, ended his days firing guns to celebrate victories in the Napoleonic wars”.

Barton did have an adventurous career, but he did not live in Admiral’s House.

Admiral’s House is Grade II listed, and I have used the Historic England history of the house in the listing record as hopefully the most accurate record for the history of the house.

Admiral Barton certainly did not build the house, and whether cannons were ever fired from the roof must be questionable.

Pamela Lyndon Travers (born Helen Lyndon Goff in Queensland, Australia on the 9th of August, 1899) was the author of Mary Poppins which features Admiral Boom, who fired a cannon from his roof. Travers was working on Mary Poppins during the 1920s (it was published in 1934).

Admiral’s House is referenced as Travers inspiration for Admiral Boom’s house. There is no record that she ever lived in Hampstead, or whether she saw the house when she was writing Mary Poppins, however as shown with the Tatler article in 1940, the story of the Admiral and cannon was in circulation in the early decades of the 20th century.

Admiral’s House as seen whilst walking along Admiral’s Walk:

Admiral’s House has been modified many times over the years. The entrance from Admiral’s Walk, along with the conservatory on the first floor which can be seen in the above photo, were both 19th century additions.

The large garage which can be seen to the right of the house is a recent replacement of an earlier structure, and the house has also had a kitchen extension and underground swimming pool added.

To the side of Admiral’s House is another building, Grove Lodge. It is not clear what the original relationship was between the two buildings, and whether there was any dependency, however they do appear to have been in separate ownership for most of their existence.

Recent building work on Grove Lodge made the national newspapers, when construction of a basement at Grove Lodge, allegedly caused damage to Admiral’s House, as reported in the Daily Mail.

If you look at the following photo, there is a brown plaque on Admiral’s House, and a blue plaque on Grove Lodge:

The brown plaque on Admiral’s House was also in my father’s 1951 photo, and is a London County Council plaque, recording that the architect, Sir George Gilbert Scott lived in the house.

He was the architect for the Midland Grand Hotel at St. Pancras Station, the Albert memorial, and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, as well as large number of other public buildings, restorations of churches and cathedrals, and domestic houses.

Prior to Hampstead, he was living in St. John’s Wood, however the continued expansion of London resulted in a move in 1856 to Admiral’s House. He would not stay there for too long, as his wife Caroline found the place rather cold and the location isolated which restricted their social life (Hampstead Underground Station would open years later in 1907).

The blue plaque on Grove Lodge, to the left, is to record that the novelist and playwright John Galsworthy lived in the house between 1918 and 1933. Galsworthy’s best known work was the Forsyte Saga, and he was awarded the Nobel prize for literature in 1932.

The house in Hampstead was his London home, and it was here that Galsworthy died in 1933.

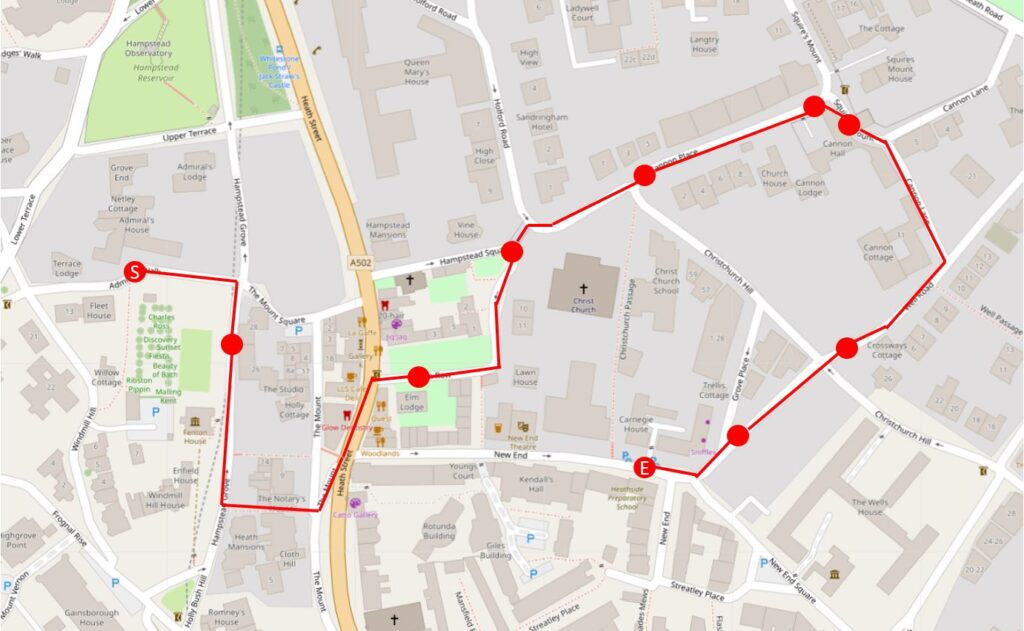

After a look at Admiral’s House, and ticking off another of my father’s photos, the weather was so good that we went for a wander around Hampstead.

The following map shows the route covered in the rest of the post with red circles indicating a place I will write about. Admiral’s House is at the start of the route on the left of the map (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

And from here, a short walk brings us to the following house in Hampstead Grove:

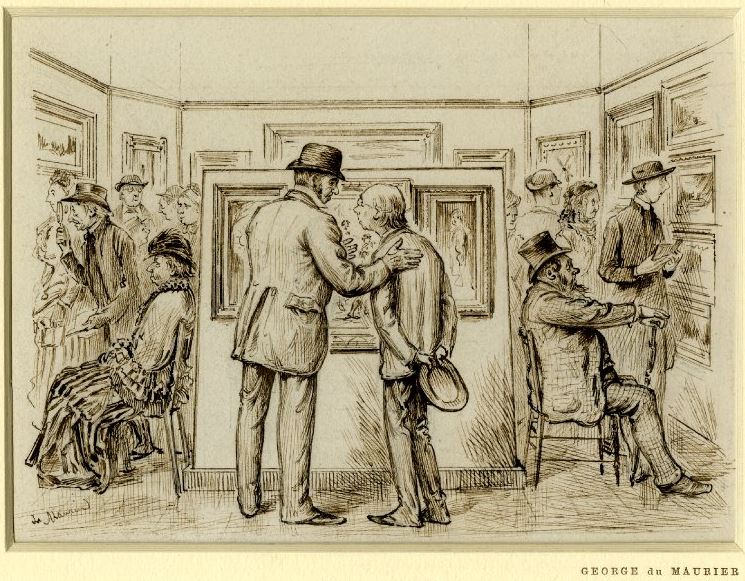

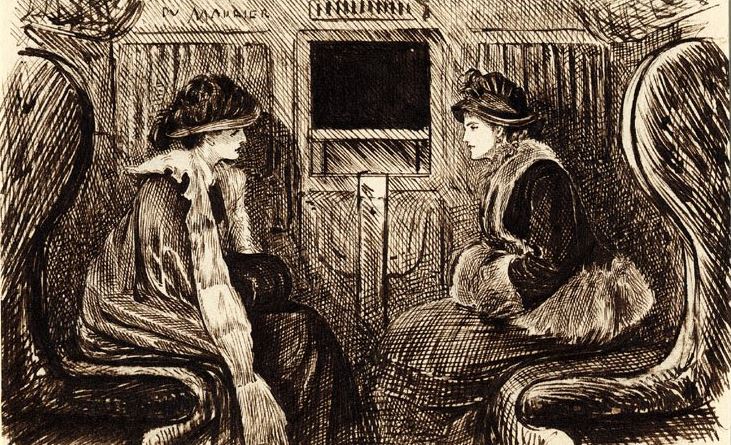

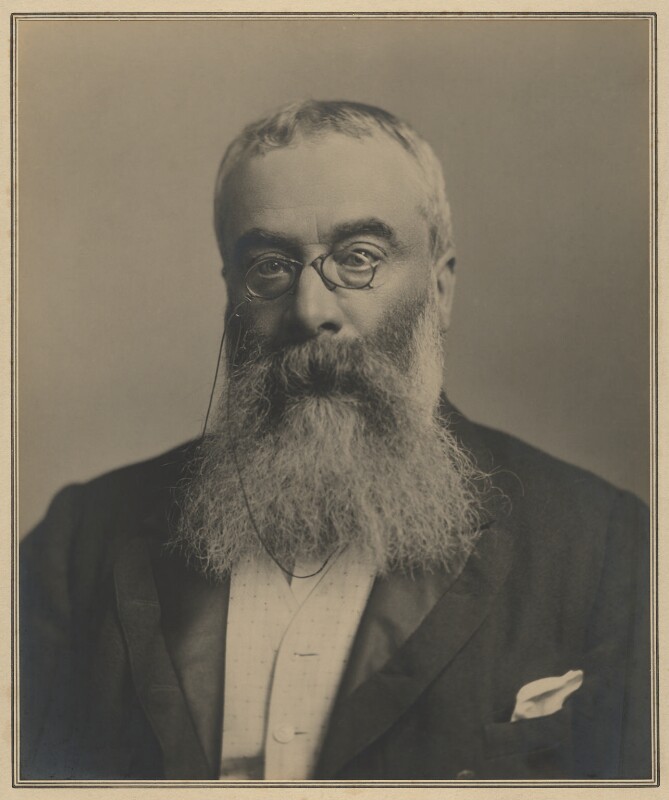

Which has a plaque recording that cartoonist and author George du Maurier lived in the house:

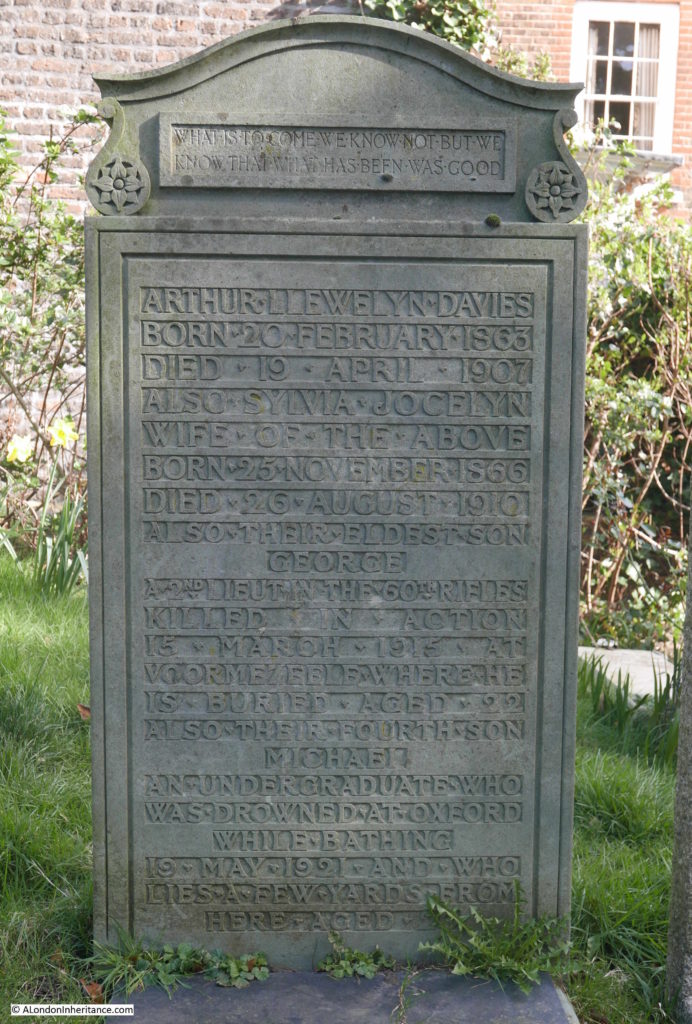

The du Maurier name has many associations with Hampstead, and I wrote about finding his grave at St John, Hampstead. in this post.

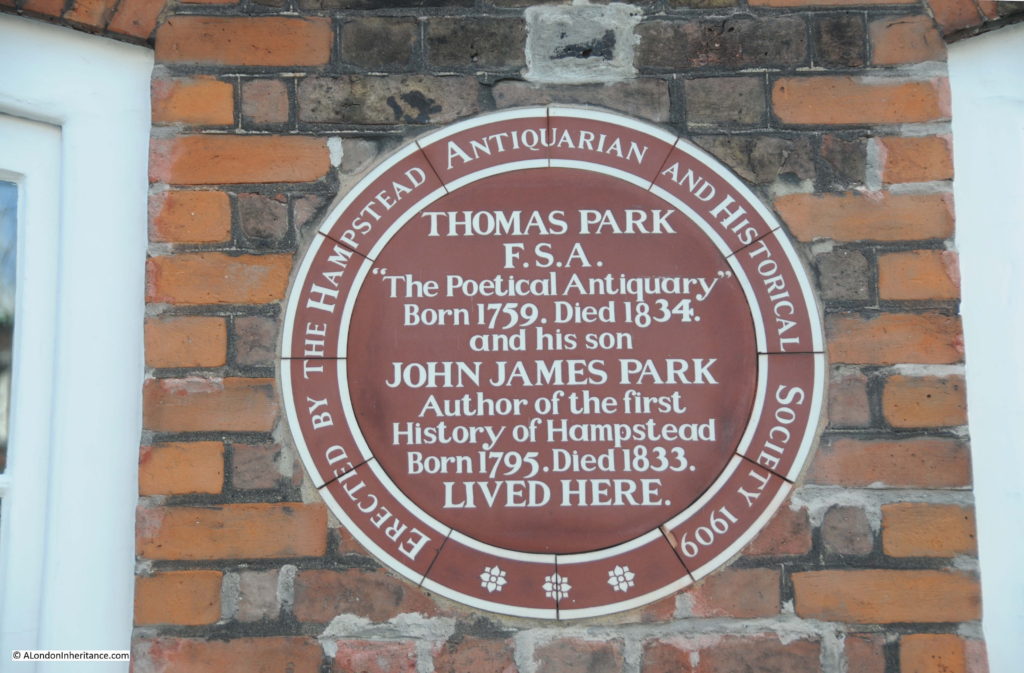

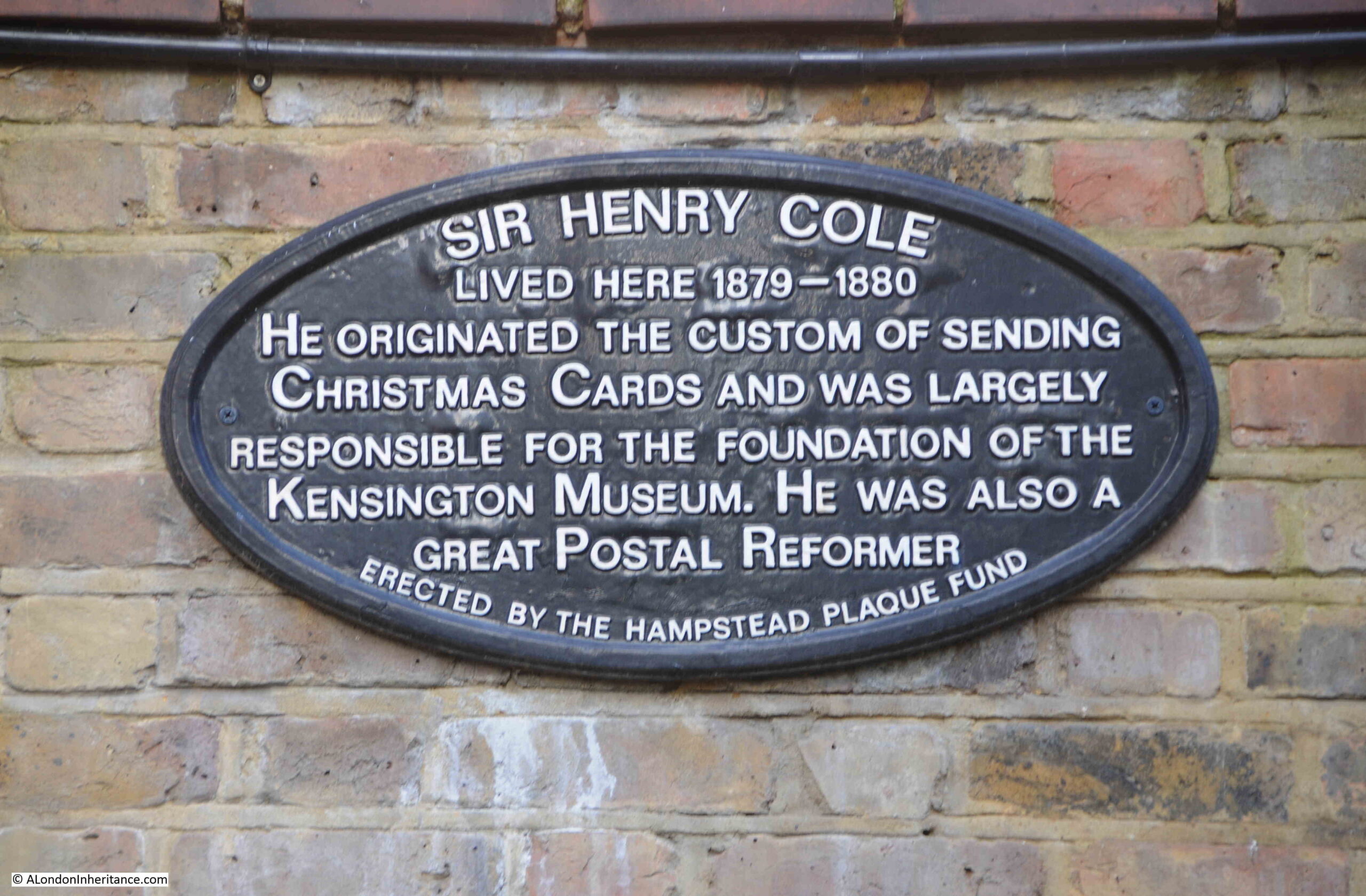

We then headed east, crossed over Heath Street and walked along Elm Row, where there is this house:

With a plaque recording that Sir Henry Cole, who “originated the custom of sending Christmas Cards” lived in the house:

Sir Henry Cole seems to have been a far more complex and busy man than the plaque suggests. He appears to have been a workaholic, and also did not suffer fools gladly (or those that disagreed with him). His obituary, published after his death in 1882, records that “It is now fifty-five years since he commenced his career of working himself and making everybody else within the sphere of his influence work also”, and that he entered public service under the Record Commission when he “allowed little time to pass before making his presence felt”.

He found the Records Commission was in a terrible state and set about reorganising the way records were kept, in such a way that brought him into conflict with a number of powerful people.

The Record Commissioners dismissed him following a feud within the organisation, however when he was proved to be right, and had gathered his own support, the Record Commissioners had to take him back, and promote him to the office of Assistance Keeper of Records.

The reference to Christmas Cards probably relates to the following entry in his obituary “He took an important part in the development of the penny-postage plan of Sir Rowland Hill, occupied the responsible post of Secretary to the Mercantile Committee on Postage, and gained one of the £100 prizes offered by the Treasury for ‘suggestions'”.

He also had concerns about standards of architecture, fashion and the design of everyday objects, stating that “In 1840 England had not yet recovered from the fearful degradation of taste under Farmer George” (the nickname given to George III), and he preached for the alliance of art and manufacture.

This is only a small snapshot of his life and his obituary ran to a full column and a quarter of news print. I suspect it was a clever marketing idea to introduce the custom of sending Christmas Cards when he was involved with the penny-postage plan.

Following Elm Row, then turning into Hampstead Square and there are two large, brick buildings. The one on the left has a brown plaque on the side:

The brown plaque reads “In memoriam – Newman Hall, D.D. Homes for the aged given by his widow”.

Newman Hall was described as “one of the oldest residents in Hampstead” when he died in 1902 aged 85. He was a Reverend and Preacher, author and artist. The titles of his book included “Songs of Heaven and Earth” and “Come to Jesus”.

The plaque refers to numbers 7, 8 and 9 Hampstead Square, which were bequeathed by the Will of Newman Hall’s wife, Harriet Mary Margaret Hall as almshouses for pensioners in 1922.

The charity, the Newman Hall Home for Pensioners exists to this day, continuing to maintain the properties in their use as almshouses.

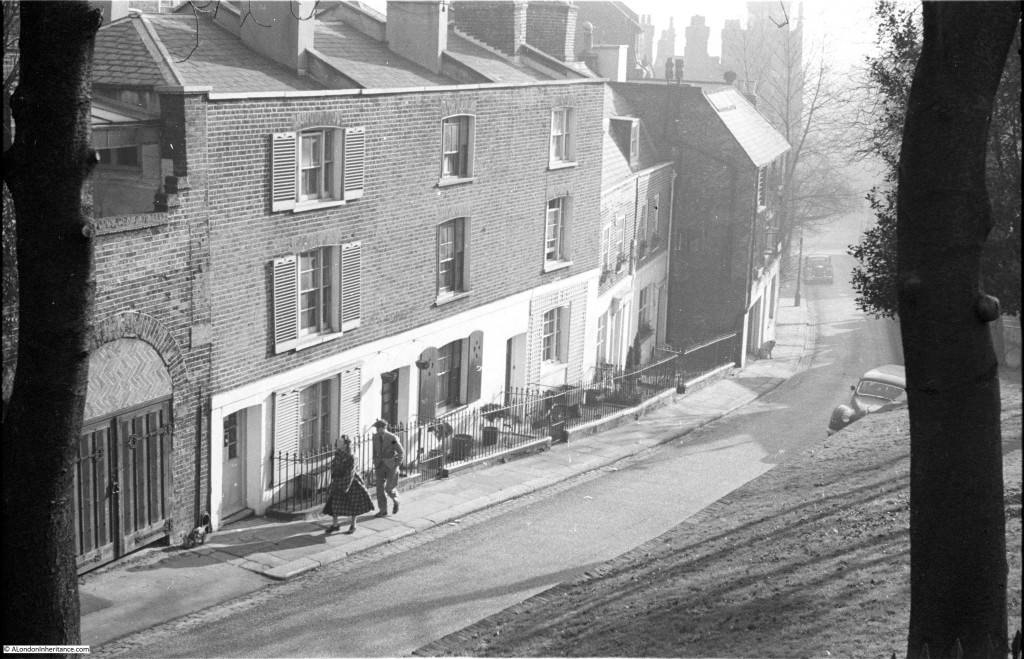

Now continuing along Cannon Place, and the view along Christchurch Hill shows the height of Hampstead, compared to the city to the south, which was one of its attractions when development started during the early 18th century.

Opposite the junction with Christchurch Hill is another blue plaque. This one to Sir Flinders Petrie, 1853 to 1942, Egyptologist:

Flinders Petrie was a prolific archaeologist of Egyptian history. He began archaeological training began in 1872, when he surveyed Stonehenge, and his first visit to Egypt in 1880 resulted in his first dig in the country in 1884 and which started a lifetime of work exploring Egyptian history.

He gathered a very large collection of Egyptian antiquities, and ensured that during excavations, everything was recorded, no matter how small.

University College London now has the Petrie Museum. This was formed around the department and museum created in 1892 through the bequest of Amelia Edwards. a collection of Egyptian antiquities.

Amelia Edwards, who for a while lived in Wharton Street on the Lloyd Baker Estate (see this post) was a 19th century novelist and author of travel books which she would also illustrate. After a visit to Egypt she became fascinated by the ancient history of the country and the threats to the archaeology and monuments that could be found across the country.

She wrote about her travels in Egypt and in 1882 also helped set-up the Egypt Exploration Fund to explore, research and preserve Egypt’s history. The fund is still going today as the Egypt Exploration Society, continuing to be based in London at Doughty Mews.

Flinders Petrie was the first Edwards Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology at University College London. The Flinders collection of Egyptian antiquities is also now in the museum that bears his name.

At the end of Cannon Place, at the junction with Squire’s Mount is Cannon Hall:

Cannon Hall dates from around 1729 and is a Grade II* listed building.

The house is another Hampstead connection with the du Maurier family, as Gerald du Maurier purchased the house in 1916 and lived there until his death in 1934.

Gerald was the son of George du Maurier who we met earlier in Hampstead Grove.

Gerald was an actor-manager and his most famous parts were probably when he played significant roles in premieres of two J.M. Barrie plays, including the dual role of George Darling and Captain Hook on the 27th of December, 1904 at the Duke of York’s Theatre.

He lived in Canon Hall with his wife Muriel Beaumont and their three daughters, Daphne du Maurier (future author and who we will meet again in Hampstead, Angela (who would also become an author), and the future artist, Jeanne du Maurier.

Canon Hall had a number of other notable, previous residents, including in 1780, Sir Noah Thomas who was physician to King George III, and from 1838, Sir James Cosmo Melville of the East India Company, who when he purchased the house was chief secretary of the company.

It seems that from around the time of Meville’s ownership, the cannons that gave the name to the place were installed along the street.

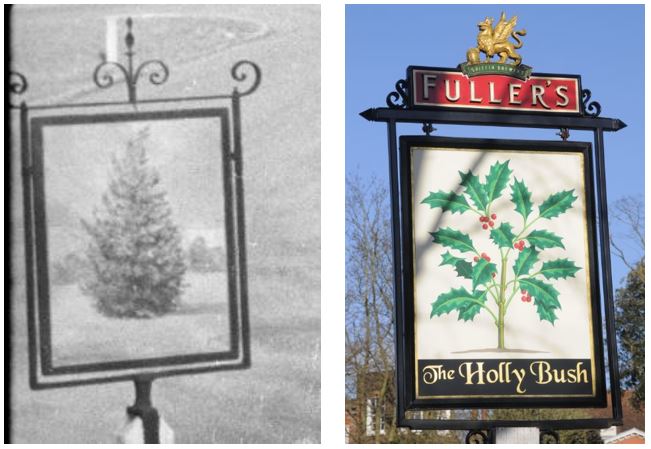

Walk past Cannon Hall, and turn down Squire’s Mount (named after Joshua Squire who purchased some land here in 1714), follow the wall alongside Cannon Hall, to find a strange door and pair of windows:

The plaque on the wall states that this was the parish lock-up, built into the garden wall of Cannon Hall around 1730. The hall was the site of a magistrates court, and prisoners would be kept in the single room cell, until more suitable arrangements could be found.

The Hampstead News on the 2nd of June 1949 stated that from old title deeds, the names of former magistrates appear to have lived in Cannon Hall. The article also stated that the lock-up later housed the manual fire engine belonging to the parish, however I doubt it would have fit through the door, unless alterations have been made to the entrance.

The lock-up lasted 100 years, as its use ended in 1832, when the temporary holding of prisoners was moved to the Watch House in Holly Walk.

The lock-up is Grade II listed, and the listing states that inside there is a vaulted brick single cell. The London Borough of Camden’s Conservation Statement for Hampstead records that on the other side of the wall, modern houses have been built in part of the garden of Cannon Hall, and the old lock-up is now the entrance to one of these houses.

Back in 2015 there was a planning application for a three storey house to be built replacing the single storey building behind the wall. I assume this did not go ahead as no evidence of such a house can be seen above the wall.

Squire’s Mount turns into Cannon Lane, at the end of which is another of the wonderful street name signs that can be found across Hampstead. Nothing like a pointing finger to indicate the direction.

At the end of Cannon Lane, we turned west into Well Lane, and soon found another mention of the du Maurier’s presence in Hampstead:

The plaque states that the novelist Daphne du Maurier lived in the house behind the wall, between 1932 and 1934. Probably best known for the books Jamaica Inn, Rebecca and Frenchman’s Creek, her last book, Rule Britannia, published in 1972, was a interesting and prophetic account of the country leaving the European Union.

Finally, towards the end of Well Road is another plaque on the walk alongside the house and buildings in the following photo:

This plaque records that the artist Mark Gertler lived in the building. He was born in Spitalfields and there is a house in Elder Street that also records his time in the area. He was a painter of figure subjects, portraits and still-life, and one of many artists that have made Hampstead their home.

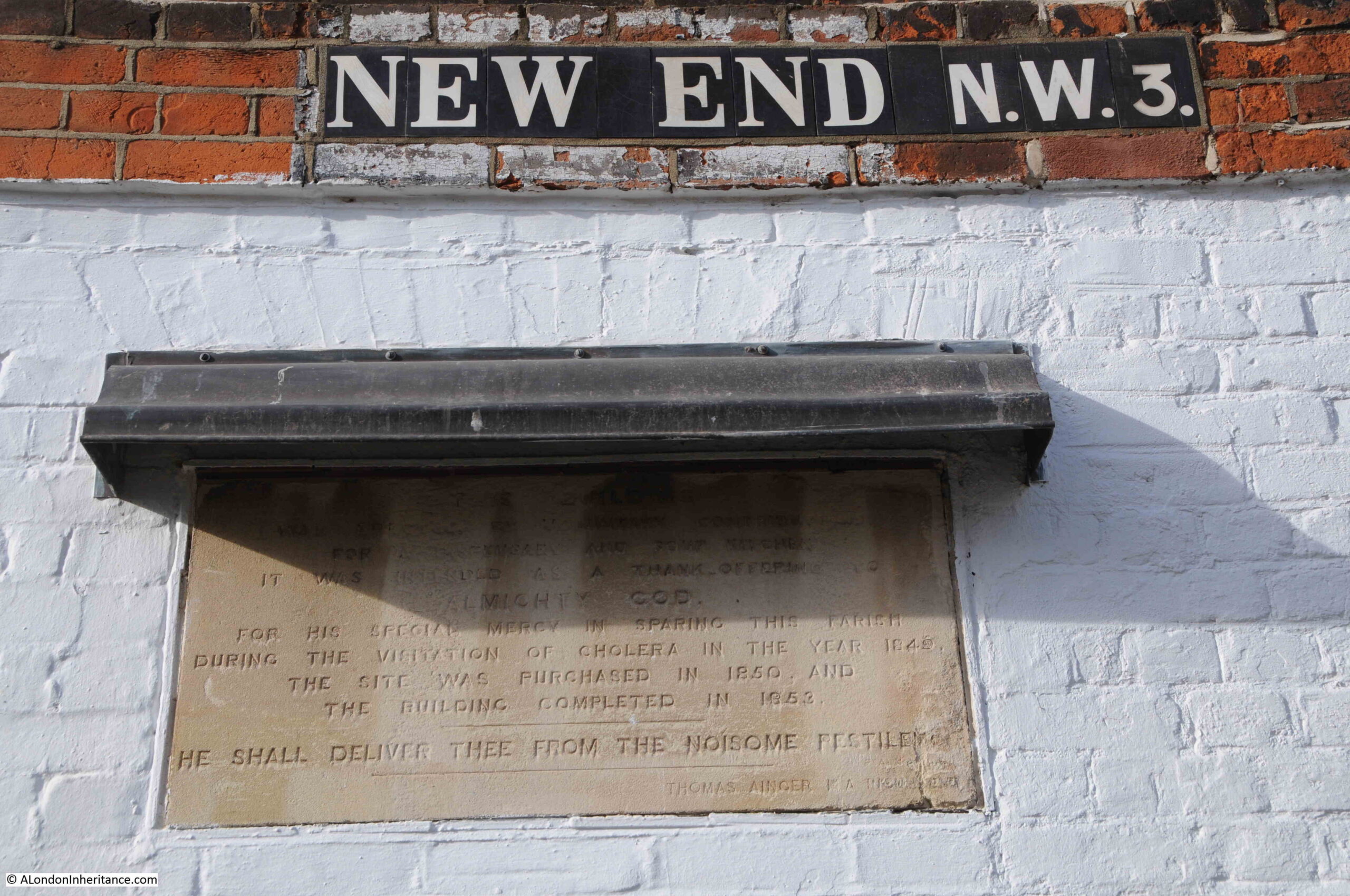

At the end of Well Road, at the junction with New End is a tall, brick building, with a stone plaque on the narrow end of the building:

The lettering along the top of the plaque is somewhat worn, but appears to read: “These buildings were erected by voluntary contributions for a dispensary and soup kitchen. It was intended as a thank offering to almighty God for his special mercy in sparing this parish during the visitation of cholera in the year 1849. The site was purchased in 1850 and the building completed in 1852. He shall deliver thee from the noisome pestilence. Thomas Ainger M.A.”

The building, that was constructed as a dispensary and soup kitchen is now a fee paying, independent school.

The visitation of cholera in the year 1849 was one of the many cholera outbreaks in the mid 19th century (see my post on John Snow and the Soho Cholera Outbreak of 1854). John Snow’s suspicion about the source of a cholera outbreak was further confirmed when a local resident of Golden Square moved to Hampstead, but still sent for a bottle of the “sparkling Broad Street water” every day. She was the only person in Hampstead to be diagnosed with cholera.

The cholera outbreak of 1849 was serious across the whole of London, although south London suffered more than north London. The Lady’s Newspaper on the 29th of September 1849 carried an account of the outbreak during the first part of the year and reported that 35 out of 10,000 inhabitants of north London died, compared to 104 out of 10,000 inhabitants of south London.

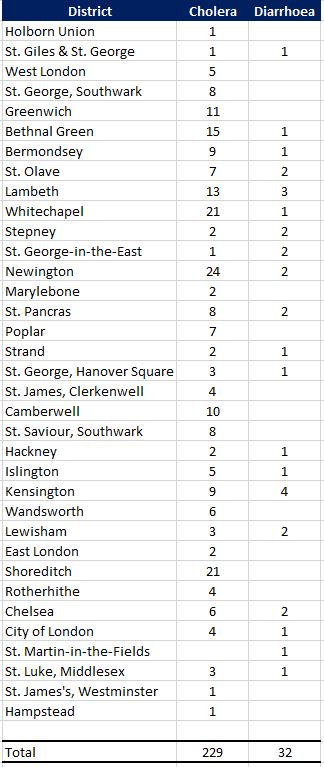

The following table from the Weekly Dispatch provides a list of deaths from Cholera and Diarrhea reported on the 31st of August 1849:

The table shows that for the reporting on that one day, Hampstead had one of the lowest levels of death across London.

That was a short walk, starting at Admiral’s House, which still looks much as it did when compared with my father’s 1951 photo.

The rest of the walk demonstrated just how much there is to explore in Hampstead. Other posts I have written about the area include: