After last week’s post covering Bermondsey, I had a number of comments and feedback via e-mail and Twitter questioning why I had used the title “New Deal for East London” when I was writing about Bermondsey which is in south London, and the same will apply to today’s post continuing on to Rotherhithe.

A really interesting point and one that got me thinking about how we split London up into different areas.

These posts are based on the 1972 Architects’ Journal article which was titled “New Deal for East London”, so I turned to the article to read their definition which I reproduce below:

“London, like Gaul is divided into three parts. The City is based on its historic centre, first and still one of the great money markets of the world, into which about 1,000,000 office workers pour each morning.

Then there is London to the west of the city, which has a widely mixed population of all classes doing all kinds of work, and contains centres of all major shopping and entertainment industries, the university and many colleges, art schools, theatres, concert halls, museums, libraries, the publishing and book selling industry, hotels, restaurants, all of which has become the centre of an immense tourist invasion every summer, held together by a good, if overcrowded road and rail network, and predominantly inhabited by a prospering, fully employed population, despite large areas of slum streets. Its comfortable suburbs stretch north, south and west to the motorways, lined with new industry, and the Green Belt beyond.

Finally, beyond the city from the Tower of London, there is the East End, largely cut off from the riverside by the docks where thousands of inhabitants have for long been employed and, despite middle class enclaves, such as Greenwich and Blackheath, this is predominantly working class London – a London of factories and warehouses, and vast council estates, replacing the meanly built streets of terrace houses that were largely shattered in the air raids of the Second World War. This is the poorest part of the capital, with the greatest need for all the social services provided (or permitted to be provided) by the local authorities, and – not surprisingly – with the highest rates.

Today this is a going-downhill area in which neither the growing tourist industry, nor the entertainment industry, nor the new light industries show any interest. Such industries prefer to expand near the prosperous West End or in some part of the country, such as the new towns, where they will be eligible for an industrial development certificate and all the financial assistance that implies.”

So that is why the Architects’ Journal included Bermondsey, Rotherhithe and Greenwich in East London, a definition with which I can fully understand and agree. East London has traditionally been that part of London east of the City, but north of the river, however I stood on Tower Bridge looking east and the river curves south around the Isle of Dogs then north around the Greenwich Peninsula, taking in an area north and south of the river which had much the same general history, industries, extent of war-time damage and post war challenges.

There are many ways of looking at London and this is why I found this 45 year old article so interesting.

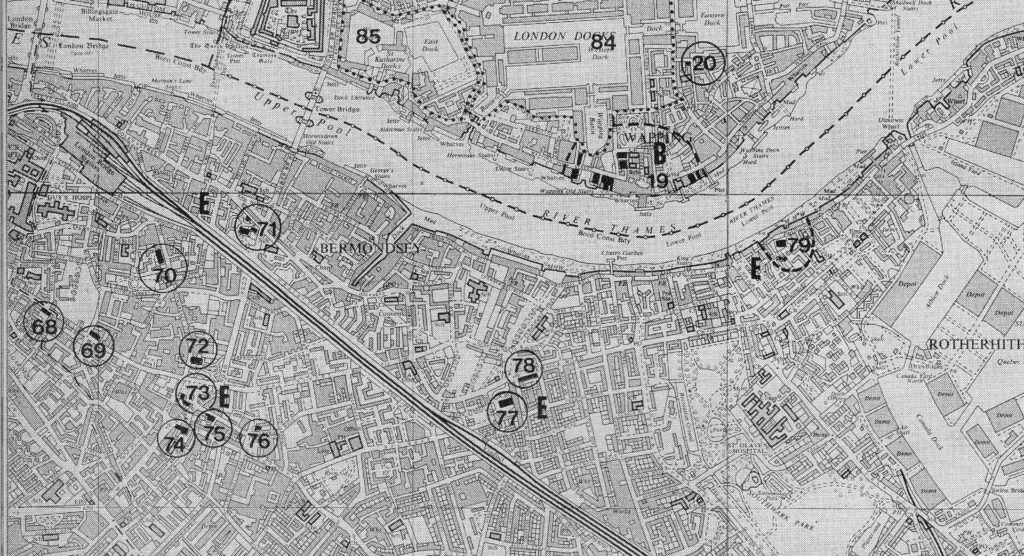

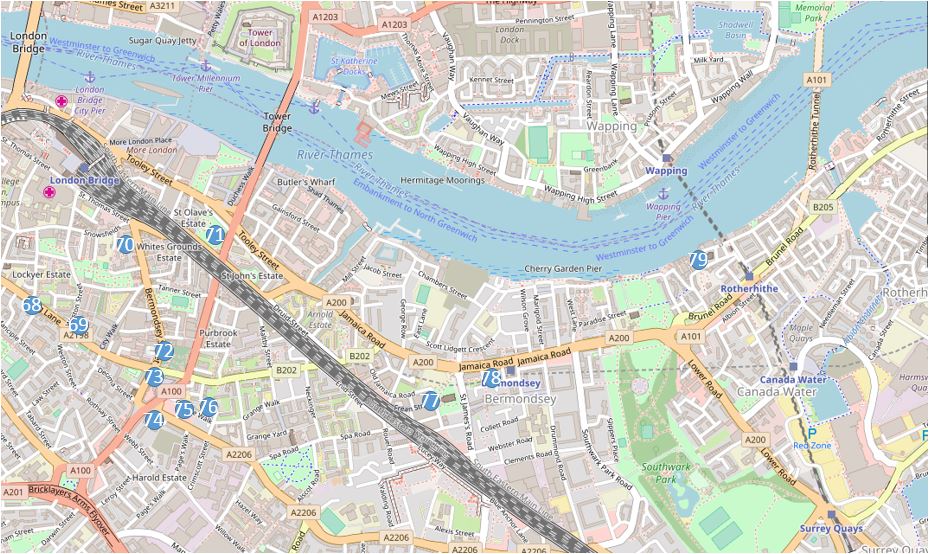

Back to the walk and in this post I am continuing on from Bermondsey to Rotherhithe to track down sites 76 to 79.

And an updated map showing the area today, with the four sites I will cover in this week’s post, sites 76 to 79.

At the end of last week’s post I was in Grange Walk and as I headed to the next location, I passed the following building on the corner of Grange Walk and Grigg’s Place:

The writing along the facade of the building facing Grange Walk announces that this was the “Bermondsey United Charity School For Girls – Erected A.D. 1830”.

I am not sure how long this lasted as a charity school as on the 1895 Ordnance Survey map, the building is labelled as a Mission Hall. It did suffer a serious upper floor fire in the year 2000, but is a listed building and at least externally, looks to have been restored to the building’s original state.

Adjacent to the school and running further along Grange Walk is this lovely row of terrace houses dated from 1890. The building in the centre of the terrace stands out due to the colour of the brickwork.

I did wonder if this was due to rebuilding after bomb damage, however the type of bricks, identical features to the other houses and that the individual brick courses run continuously along the terrace indicates that this is all original. I suspect that for some reason the brickwork on this single building has been cleaned. It does show what the terrace would have looked like when built, before being darkened by the city’s dirt.

Almost opposite this terrace of houses I found my next location:

Site 76 – Single House Of About 1700

The map shows this building slightly further on, at the junction with Fendall Street, however there is green space there now, with flats behind and this building is very close to the map location and fits the description.

The first thing I noticed about the building was the faded sign on the corner:

This reads “Spaull & Co Ltd” – who were a clay pipe manufacturing company in operation from 1880 to 1942.

Perhaps surprising that a company manufacturing clay pipes should have lasted to 1942, however the company started selling other products, and in later years in Kelly’s Directory they were listed as a Glass and Bottle Merchants.

The factory was located in nearby Westcott Street and later in Bermondsey Street and the building in Grange Walk was used as the company offices and also as a place for workers to stay in the attic rooms.

The front facade of the building which now looks to be a private house:

Continuing along Grange Walk and another terrace of 19th century houses:

My next location was almost at Bermondsey Underground Station, so I headed in that direction along Grange Road where I found “The Alaska Factory”:

The Alaska Factory was originally the firm of C.W. Martin & Sons Ltd, a company that had its roots in a business set up in 1823 by John Moritz Oppenheim to process seal fur.

The first factory was built on this site in 1869. a date confirmed above the original archway entrance to the factory which also includes a relief of a seal above the date with the words Alaska Factory on either side. The name Alaska refers to one of the main sources of seal fur which, along with Canada, and earlier the Antarctic kept the factory busy and 19th century and early 20th century fashion supplied with furs.

Over hunting of seals led to entirely predictable results, so the company expanded into general furs with the factory working on the processing and dying of new fur along with the reconditioning of fur that had already been used.

Whilst the gates onto Grange Road are from the original factory, the factory building we see today dates from a 1932 rebuild, which was designed by the firm of Wallis, Gilbert and Partners who also designed the magnificent Hoover building on the A40.

The factory has long since closed, and followed the inevitable route for most buildings in London, having been converted into flats.

From Grange Road, I turned into Spa Road, where opposite Bermondsey Spa Gardens I found the old public library:

This magnificent library building was constructed between 1890 and 1891 and opened as the first free public library in London. A large hall was added to the rear of the building in the 1930s.

Today, the building is occupied by Kagyu Samye Dzong London as a Tibetan Buddhist Meditation Centre.

The plaque still on the wall of the library building records the names of the commissioners, architect and builder:

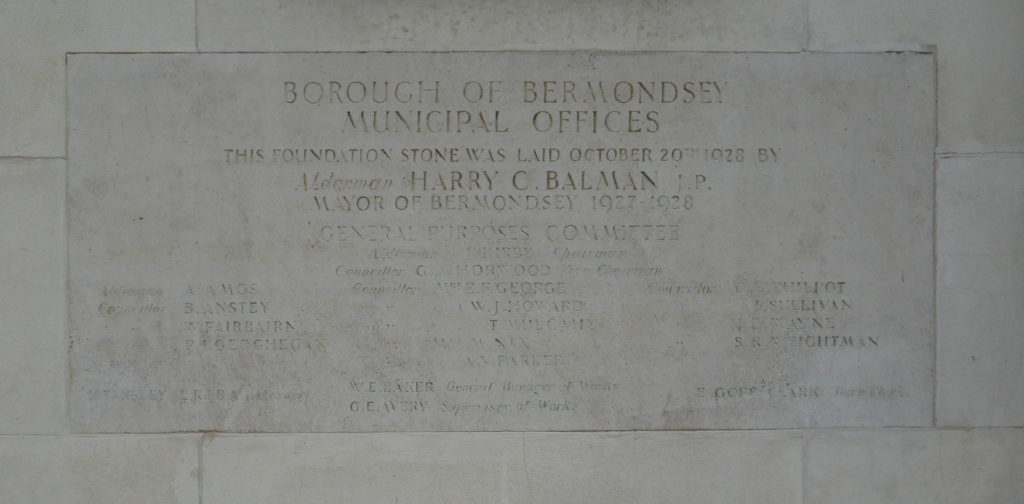

A short distance further along from the library are the Borough of Bermondsey Municipal Offices:

Built during the late 1920s on the site of Bermondsey Public Baths and Wash Houses, and adjacent to the original Bermondsey Town Hall which was badly damaged during the last war and later demolished, the building was the home of Bermondsey Borough Council, until Bermondsey was integrated into the London Borough of Souuthwark.

The building has since been converted into, yes you probably guessed this, in the region of 40 new apartments.

The original foundation stone on the side of the building:

A short distance along Spa Road is the old Queen Arms pub. Long closed, and in the past subject to planning applications for demolition, the building has survived, converted to flats, and retains original signage. Unfortunately it will not be possible to play pool and darts or listen to the jukebox whilst drinking chilled continental lagers – the 1980s equivalent of craft beers.

Walking along Spa Road, I passed again under the railway viaduct to the junction with Thurland Road where I found my next location:

Site 77 – Early 19th Century St. James Church By Savage

At the end of the 18th century and start of the 19th, the population of Bermondsey was expanding rapidly and the area needed a church to serve those moving into the area.

St. James’ is one of the so called Commissioners Churches as it was a result of the Church Building Act of 1818 when Parliament voted money for the construction of new churches.

A group of local churchman purchased the land for the church and were given a grant by the Commissioners of the fund provided by Parliament for the construction of the church.

Construction of the church was delayed whilst additional funds were raised to build both a tower and a spire. This was achieved by building a crypt under the church were space was sold for burials, thereby allowing the money to be raised for construction of the tower, topped by a spire which we see today.

John Savage was the architect, the first stone was laid in February 1827 and the church was consecrated one year later in May 1829.

The interior of the church has recently undergone a full restoration and the use of light colours and high windows brightened the church on an otherwise grey day.

Looking towards the entrance to the church with the organ above:

Roof of the church:

The font:

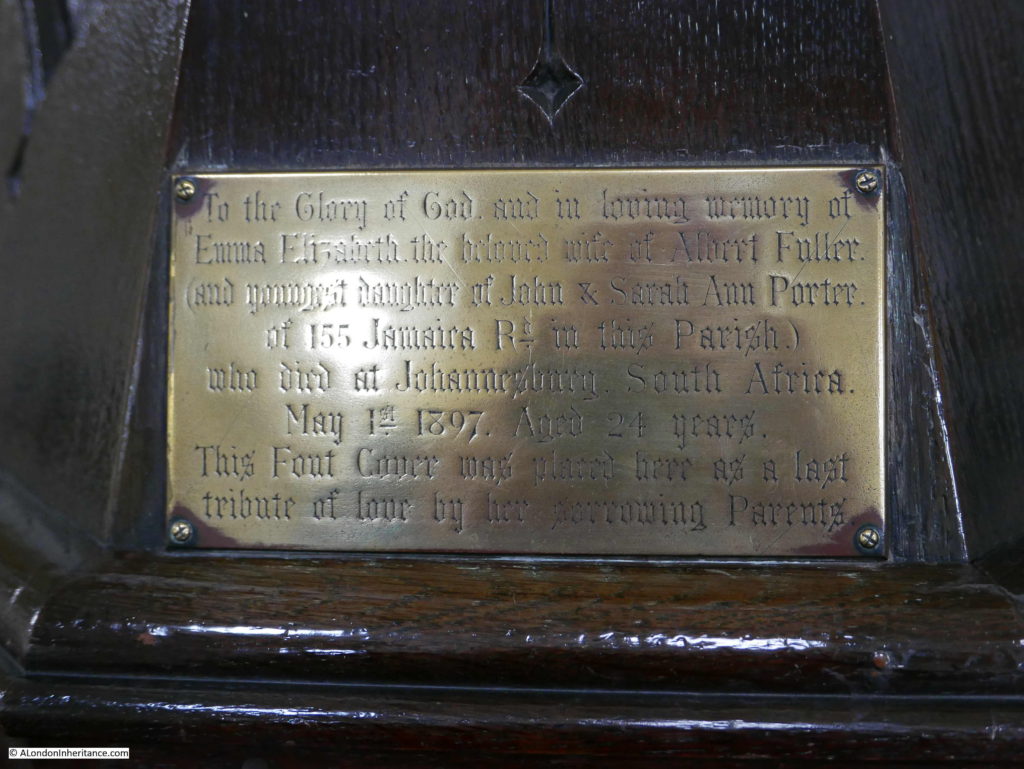

The font cover has an interesting plaque:

The plaque reads:

“To the Glory of God and in loving memory of Emma Elizabeth, the beloved wife of Albert Fuller and youngest daughter of John & Sarah Ann Porter of 155 Jamaica Road in this Parish who died at Johannesburg, South Africa, May 1st 1897. Aged 24 years. This Font Cover was placed here as a last tribute of love by her sorrowing parents.”

The loss that the parents felt for their daughter is clear from the inscription. Jamaica Road is just outside the church of St. James, and the plaque tells not just a story of the parents grief, but how in the 19th century, people from across London, including the local streets of Bermondsey, were travelling the world. It would be interesting to know what Emma Elizabeth was doing in Johannesburg in 1897.

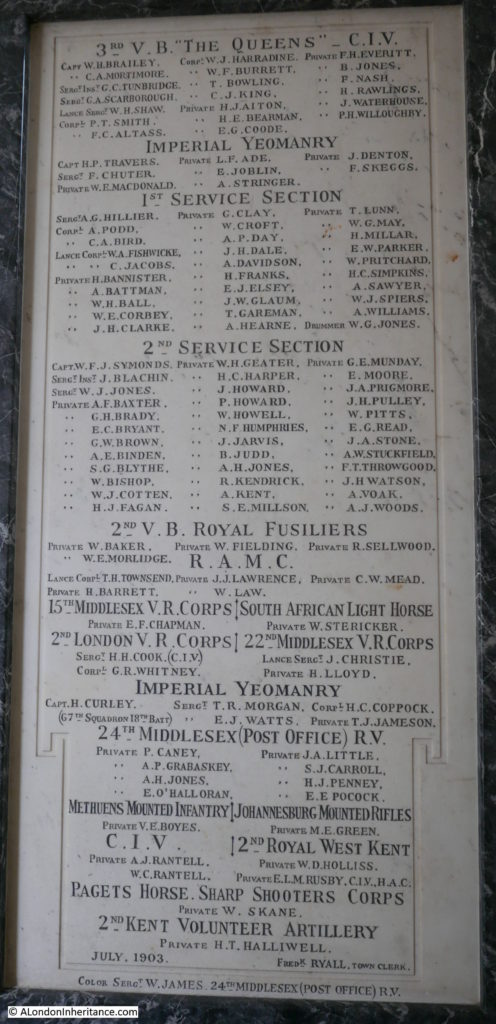

Another plaque in St. James also tells a story of local Bermondsey people who died in a foreign country. This is the Bermondsey Boer War Memorial:

The memorial was unveiled in 1903 in the original Bermondsey Town Hall in Spa Road (next to the Municipal Offices that we met earlier). The Town Hall suffered badly from bomb damage during the Second World War and was finally demolished in the 1960s. The memorial was stored in a council yard, and when that yard was in turn closed, a suitable location for the memorial was looked for, with St. James being a logical home for a memorial to local Bermondsey solders.

Time to walk to the next location, but a final view across the churchyard to St. James:

Just outside the churchyard is the Gregorian pub. An interesting architectural style that would perhaps be more at home a bit further out in the south London suburbs, however really good to see a pub which is still open.

A short distance further along Jamaica Road, just before reaching Bermondsey Underground Station I found the next location:

Site 78 – 18th Century Terrace

The terrace consists of two houses with two floors and an attic floor, and two houses with three floors:

These survivors from the 18th century now look out onto a very busy Jamaica Road and have the Jubilee Line running underneath.

Walking to my next location, I found Jimmy’s & Sons Barber Shops also in Jamaica Road.

Traditional Barber Shops are another of my photographic themes whilst walking London – this started with the photos my father took, including these from the mid 1980s.

Unfortunately what with passing traffic and trees, i could not get a perfect photo of the shop front.

To reach the next location, I cut down from Jamaica Road to the river, and walked along to:

Site 79 – Rotherhithe Conservation Area Round 1714 St. Mary’s Church

Rather than a single, or terrace of buildings, site 79 in the Architects’ Journal referred to an area clustered around the church. The risks to these types of street and buildings are clear from the following text from the 1972 article:

“As with the north bank, it was riverside villages that first grew in size and expanded in a linear form along the river. Rotherhithe still retains its early 18th century church and school. The last substantially 18th century street – Mayflower Street – was demolished in the 1960s; and Rotherhithe Street has recently lost the remainder of its early 18th century riverside houses. These losses are made ironic by the recent decision to make Rotherhithe a conservation area.”

Statements like this really bring home the opportunities lost in the decades after the war to retain and restore so many historic streets and buildings.

I walked towards the church at Rotherhithe through the start of Rotherhithe Street from Elephant Lane where Rotherhithe Street is a walkway between old warehouse buildings.

The walkway opens out to the wider road where the church is located. The entrance to St. Mary’s Church from Rotherhithe Street:

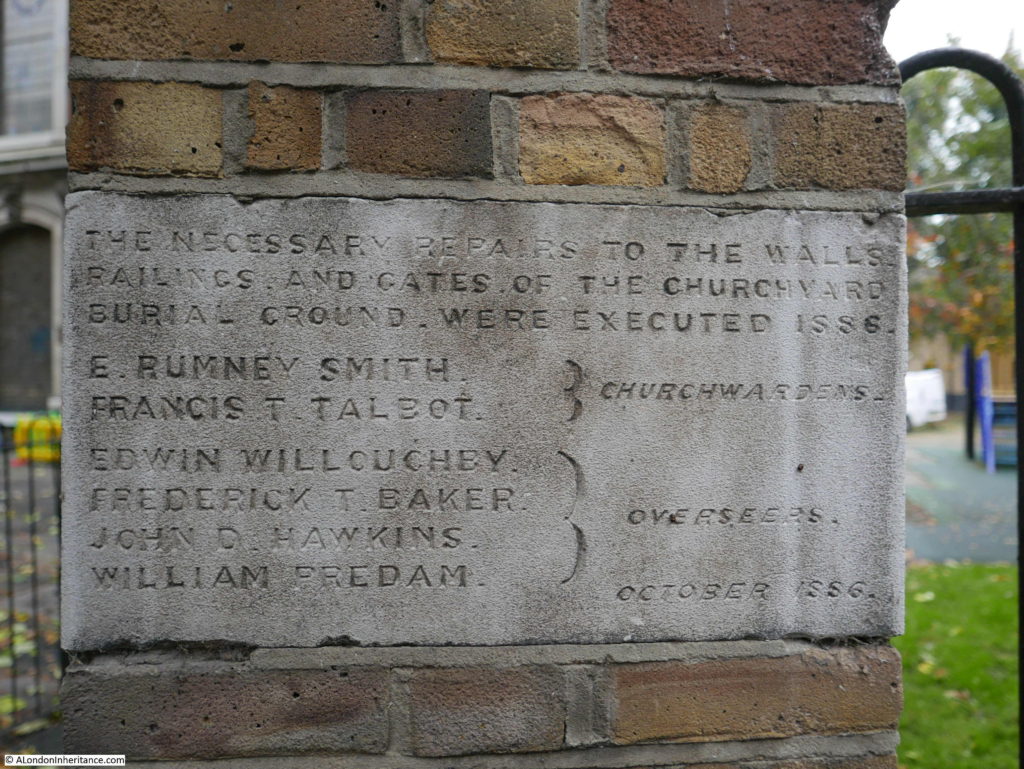

With plaques recording work carried out around the churchyard in the 19th century:

St. Mary’s Church from St. Marychurch Street on a grey and overcast September day.

The St. Mary’s that we see today dates from around 1714 with the tower and spire being added a few years later. The spire was rebuilt again in 1861. According to Old and New London, the “church was built on the site of an older edifice, which had stood for four hundred years, but which had become at length so ruinous that Parliament was applied to for permission to pull it down. The present church has lately been thoroughly restored and the old unsightly pews of our grandfathers’ time have been superseded by open benches.”

Plaques on the church record the sailing of the Mayflower and also work to underpin the tower of the church:

The church, as does much of Rotherhithe, deserves a dedicated post, however for the purposes of this post, I will continue walking around the conservation area identified in 1972.

Across the road from the church is the old churchyard, which is now St. Mary’s Churchyard Gardens. To the left of the churchyard is this old watch house dating from 1821, used for watchmen to provide a lookout over the churchyard for any nefarious activity including any attempted body snatching.

To the left of the watch house is a building that once housed a charity school:

As recorded on the plaque on the front of the building, the school originally dates from 1613 and moved into the building we see today in 1797. The plaque also has the blue coated children, typical of a charity school on either side. See also this post of another charity school across the river in Wapping.

Early 19th century building that formed part of the Hope Sufferance Wharf:

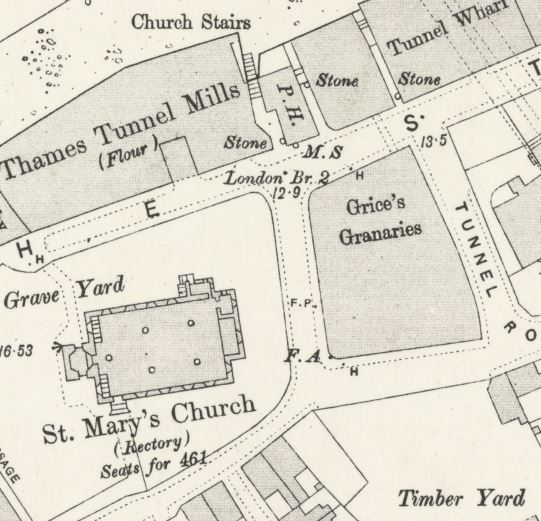

Late 18th century Grice’s Granary warehouse on the corner of St. Marychurch Street and Tunnel Road:

The blue plaque records that the Rotherhithe Picture Research Library and Sands Film Studio has been established in the building since 1976.

Tunnel Road is a clue that we are close to the Rotherhithe end of the first tunnel under the River Thames. At the junction of Tunnel Road and Rotherhithe Street we can see the Brunel Museum building. My post on walking through the tunnel can be found here.

The tower and steeple of St. Mary’s Church can be seen in the background of this print showing the diving bell used in the construction of the Thames Tunnel:

Where St. Marychurch Street curves around the church and meets Rotherhithe Street is the Mayflower Pub.

A plaque on the wall claims that the pub was built in the 17th century, however whilst a pub may have been on the site since the 17th century, the current pub building is more recent with the latest rebuild being in the 1950s.

Embedded in the front of the pub is a milestone indicating that the pub is 2 miles from London Bridge:

I am not sure of the age of this milestone, however in the 1895 Ordnance Survey map (see below), the letter M.S. indicates that the milestone was in front of the pub and 2 miles from London Bridge at the end of the 19th century:

There are other old signs on the side wall of the pub, including two parish boundary markers for St. Mary, Rotherhithe and a rather nice Right of Way sign by the Metropolitan Borough of Bermondsey:

And finally, before I walk back into central London, a view of one of the windows of the Rotherhithe Picture Research Library and Sands Film Studio on Rotherhithe Street:

And that concludes my two posts covering a walk from Bermondsey to Rotherhithe, the sites which the Architects’ Journal described as “Medieval village centres along the southern river bank and around London Bridge”.

In the same category, the article continued on from Rotherhithe to Greenwich, this walk will have to wait for another day when hopefully the weather will be better.

Apologies for the length of this post, however this is a fascinating area and there is much to discover. I have only lightly scratched the surface in these two posts, but it was a really enjoyable walk which I thoroughly recommend.