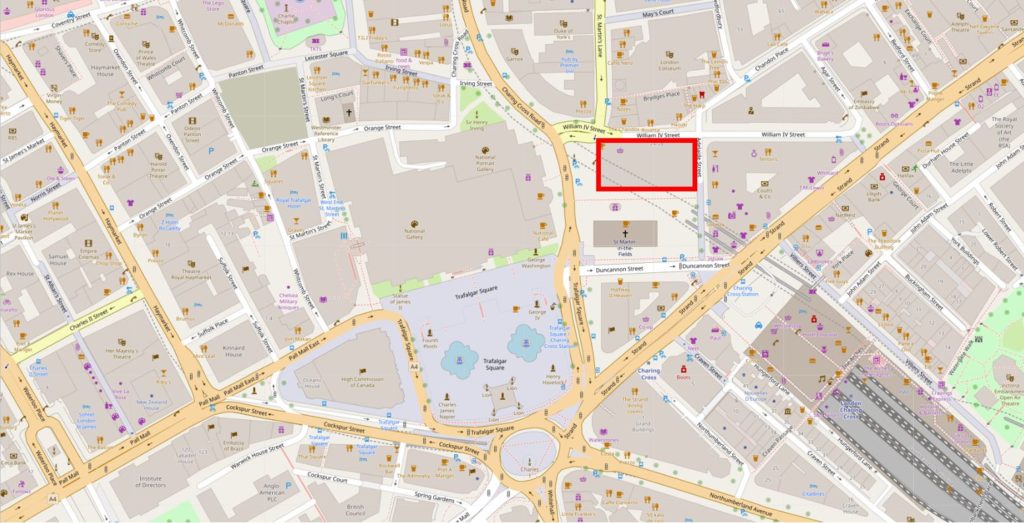

In this week’s post, I am exploring the church of St Martin in the Fields, and also at the end of the post I have my first Sunday of the month feature on Resources, where I look at some of the resources available to help explore the history of London. In this months Resources, I am looking at a source of Historical maps of Southwark (and the rest of London) and a series of maps showing the boundaries of Wards of the City of London..

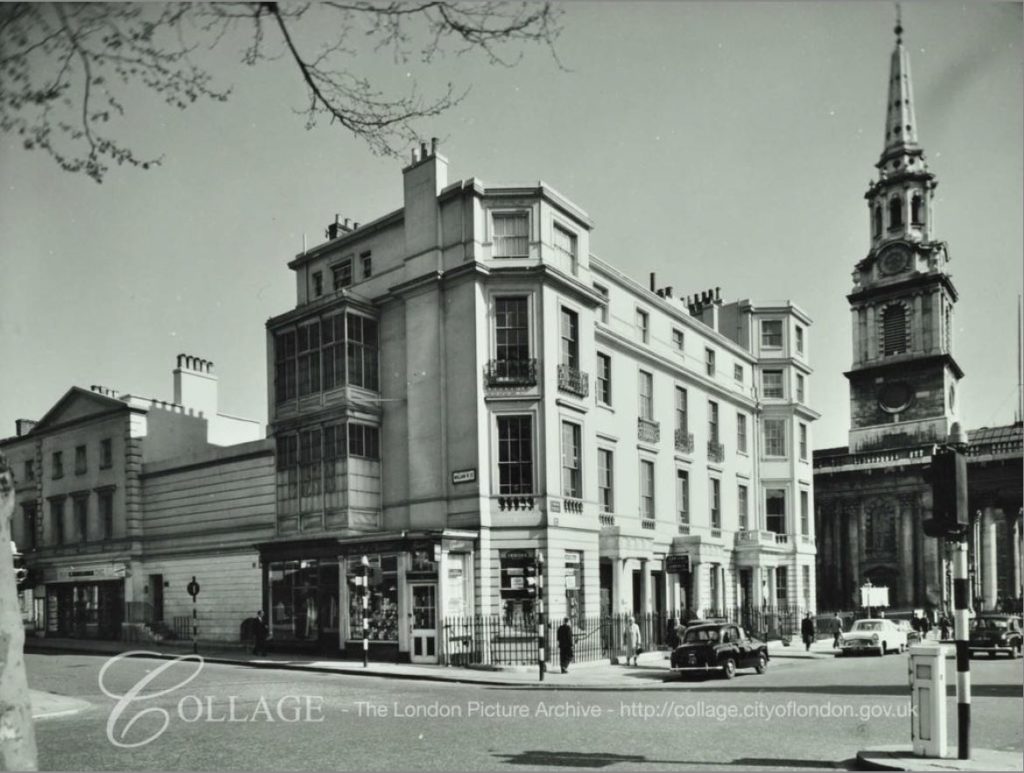

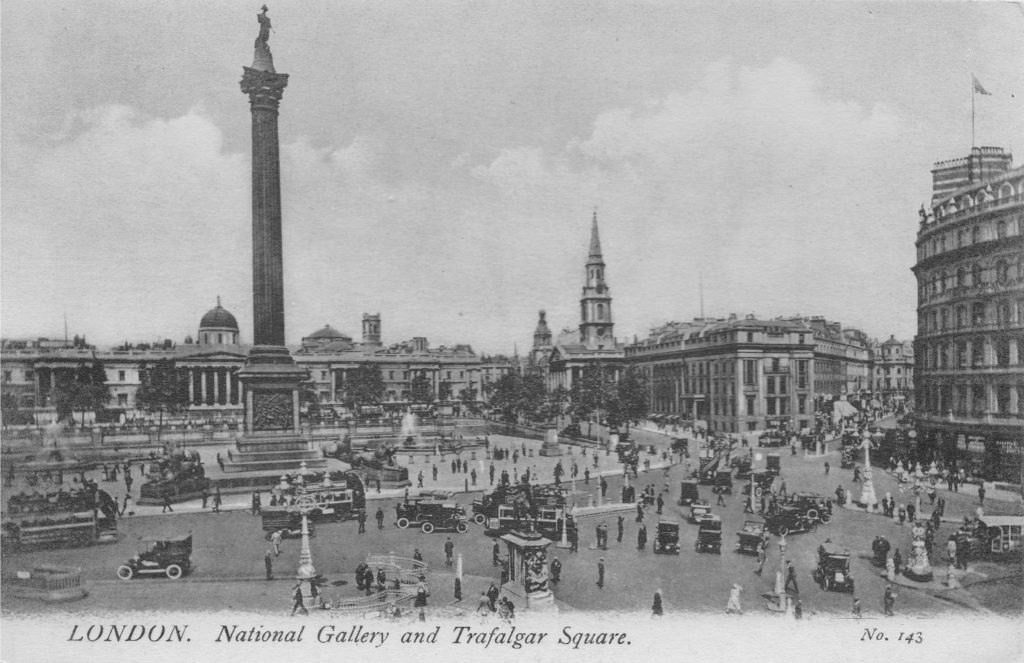

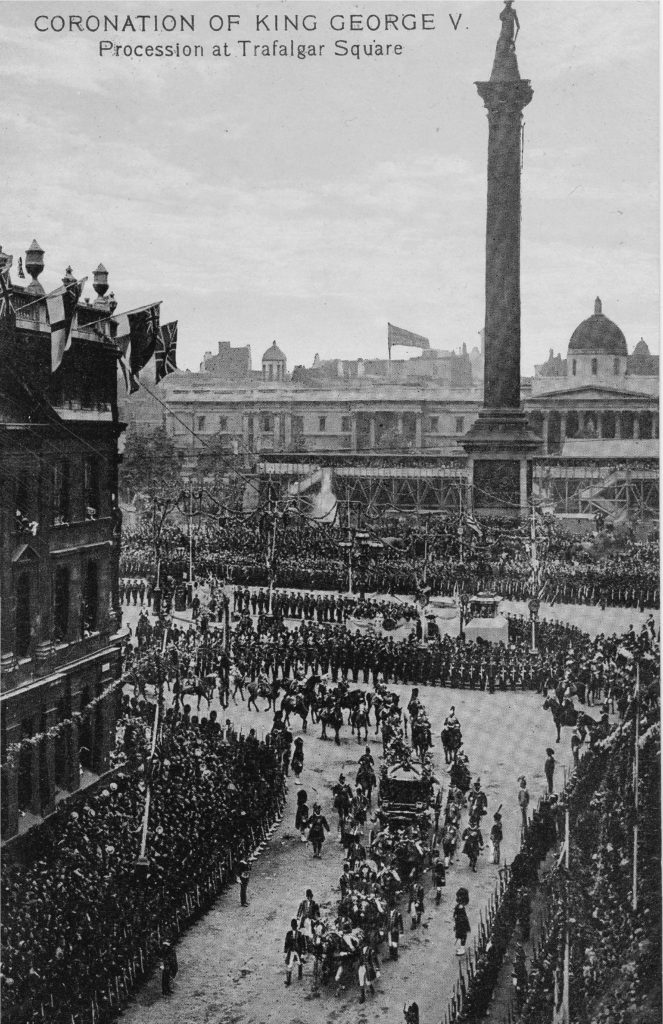

But first, St Martin in the Fields, a very prominent church on Charing Cross Road and at the north eastern edge of Trafalgar Square, with the prominent tower and steeple looking out over the square and the National Gallery:

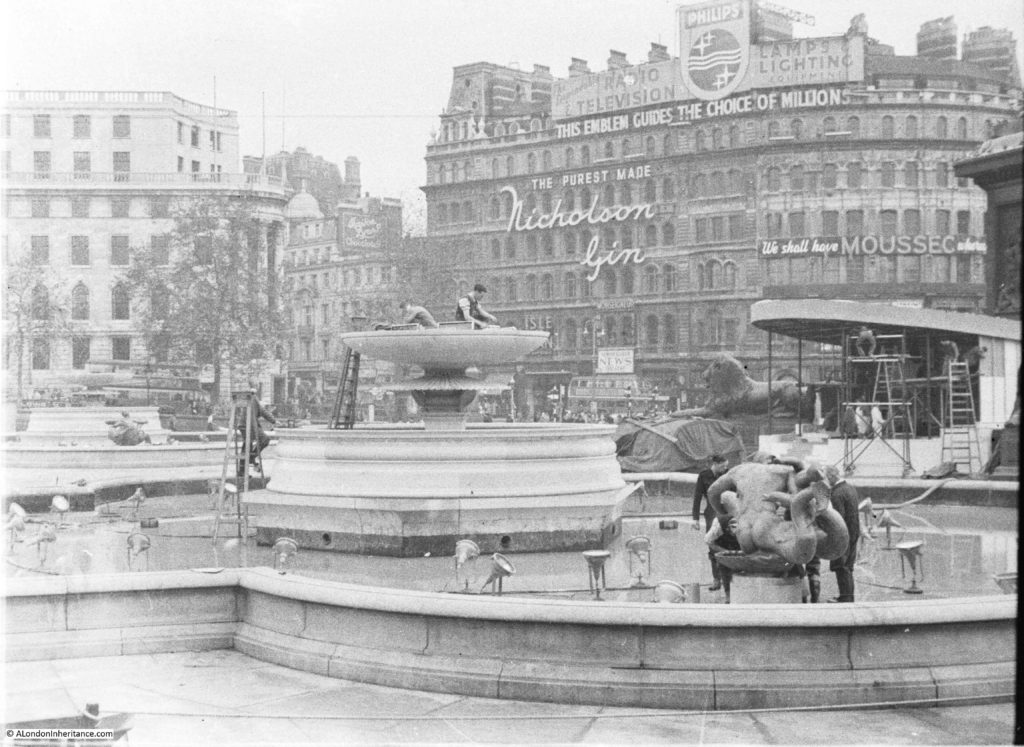

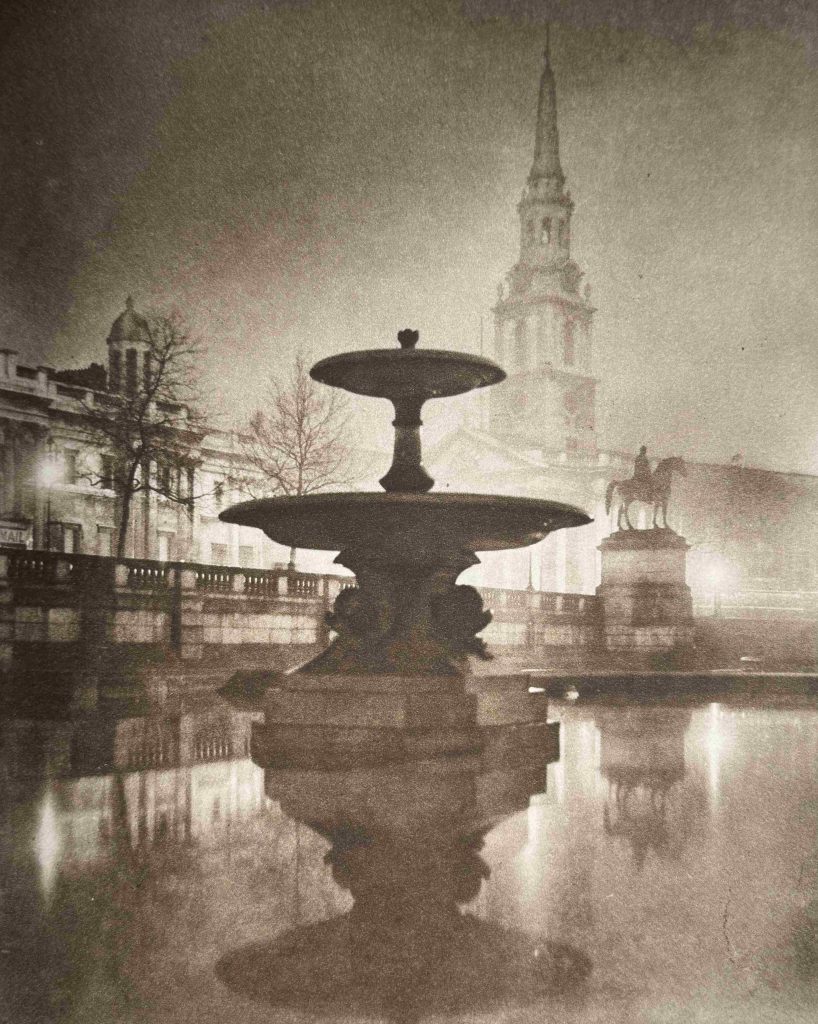

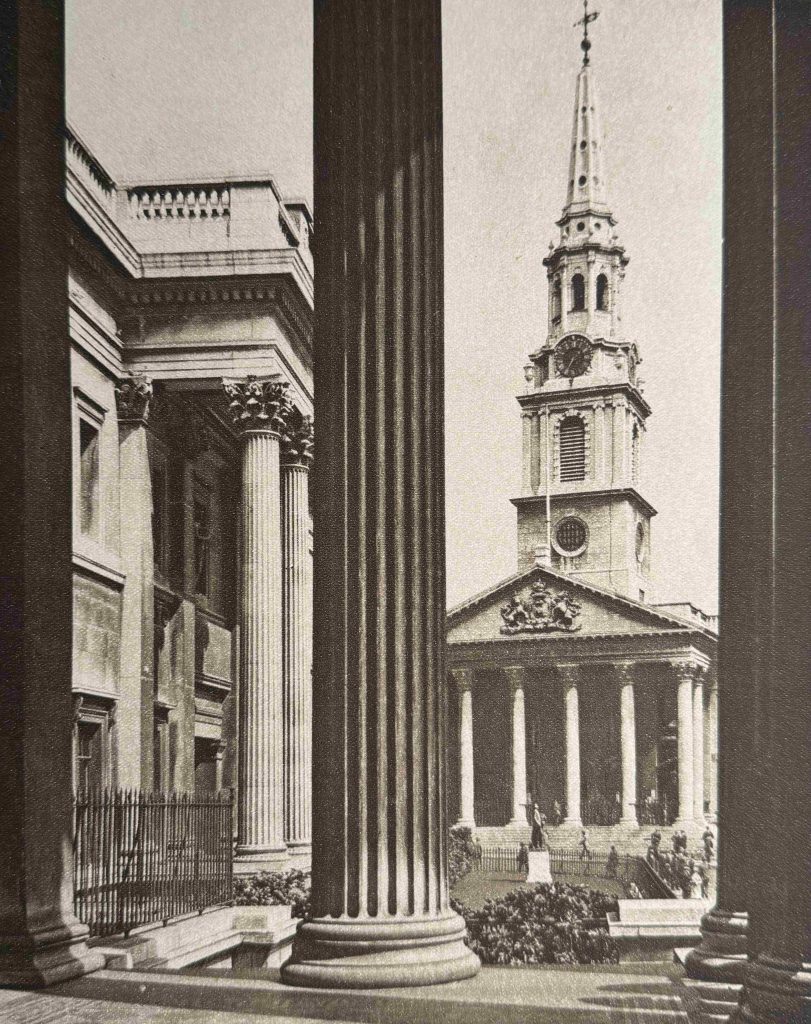

A similar, but very moody view of the church through a Trafalgar Square fountain in the 1920s:

The St Martin in the Fields that we see today was designed by James Gibbs and completed in 1726:

The current church was built on the site of a much earlier mediaeval church, with the first mention of the church dating back to 1222, when it would have been mainly surrounded by fields, although just to the south was the important road running from the City to Westminster and the small village of Charing.

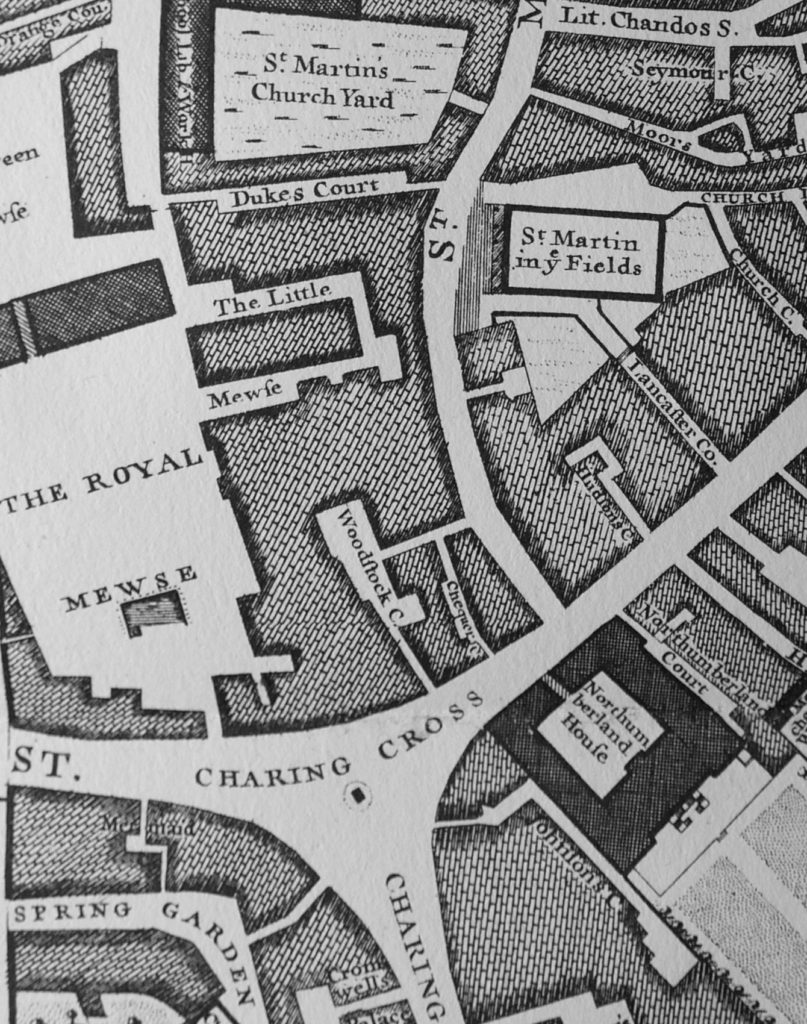

We can see the original church in Morgan’s 1682 map of London, by which time most of the surrounding area had been transformed from fields to streets:

The Mews Yard and St Martin’s Church Yard are where Trafalgar Square and the National Gallery are today.

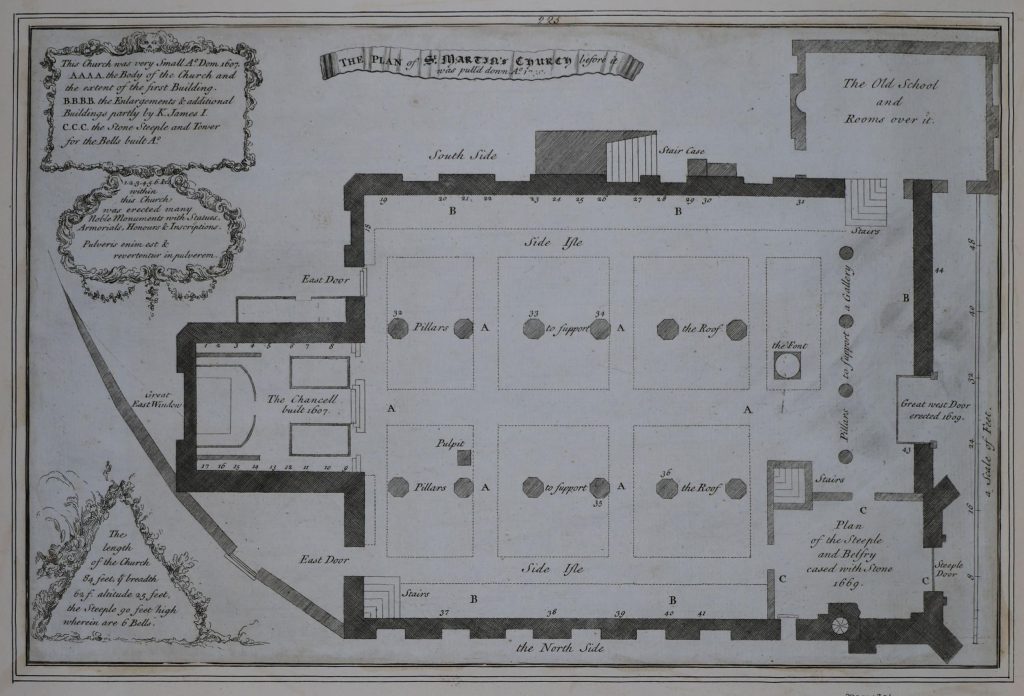

A plan of the mediaeval church was produced shortly before it was demolished. The plan shows a relatively small, simple church with a length of 84 feet, width of 62 feet, height of 25 feet and a 90 foot high steeple which contained 6 bells (© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.):

The church had been extended in the 17th century with the Chancel to the left added in 1607, and the steeple and belfry being cased in stone in 1669, so it was a smaller building prior to the 17th century.

At upper right is marked a school room with rooms above.

Old and New London by Edward Walford includes a drawing of the west view of the church, as it appeared before demolition. The view matches the above plan, with the tower on the left corner, and the school room and rooms above on the right, extending from the side and front of the church:

As with so many medieval churches across London, by the early 18th century St Martin in the Fields was in a very poor condition. A survey of the church identified that the decayed walls made mainly of rubble, had been spread out by the weight of the roof, and the fabric of the church was unable to continue providing sufficient support.

A new church was needed, and as the church was now serving a large, built up area, rather than a small village with surrounding fields, an impressive and larger church was required.

A new church was included in the 1715 list of “Fifty New Churches”, however there was very little progress, and the majority of the fifty churches would not be built due to cost.

The Church Vestry petitioned Parliament and in 1717 an Act was passed to rebuild St Martin, with the costs being covered by the inhabitants of the parish.

Designs for a new church were requested from architects of the day, and George Sampson, Sir James Thornhill, John James, Nicholas Dubois and James Gibbs submitted plans in 1720.

James Gibbs design was chosen, the old church was demolished between April 1722 and January 1723, and construction of the new church commenced.

James Gibbs plans went through a number of iterations. His first plan for the new St Martin’s was for a round church with a large dome – almost a mini version of St Paul’s. There were issues with the overall size of the plot, the need to house memorials from the old church, provision of a temporary site of prayer during construction, the encroachment of nearby houses etc.

Gibbs came up with a final design which addressed these issues, as well as the costs of a large, domed church, and produced a more traditional rectangular design in early 1721.

Minor design changes continued during the construction process, although a major change was made in 1722 to “increase the breadth of the portico”, a change that would result in the impressive front and entrance to the church that we see today, and which brough the front and the steps up to the church, up to the edge of St Martin’s Lane.

In the spring of 1724, the core of the church, consisting of brick and Portland stone, had been completed and construction moved on to the fitting out of the new church with carpenters, plasters, plumbers etc. submitting proposals for how this would be completed. This work included cast iron railings to surround the churchyard.

The total cost for the new church was £22,497.

A rather strange event was held to celebrate the completion of the new St Martin in the Fields. Tomas Cadman, who was known as the Italian Flyer, descended head first along a rope stretched from the top of the steeple to the Royal Mews opposite.

The new St Martin in the Fields not long after completion, as shown in a print dating from 1754 (© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.):

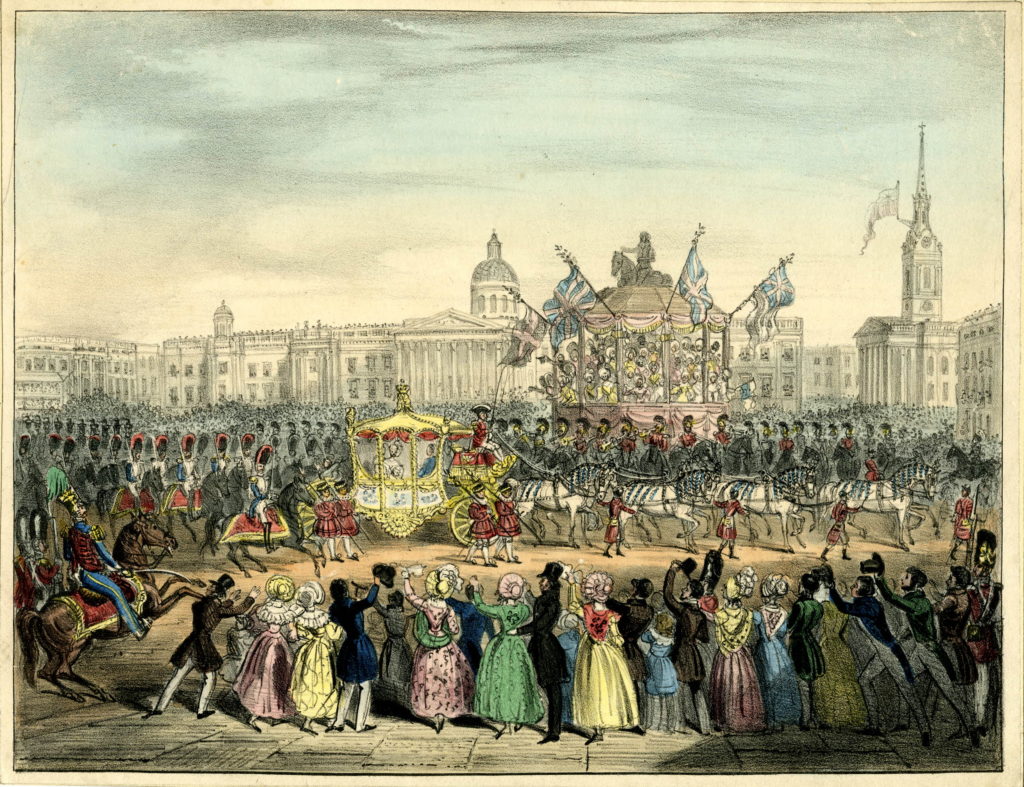

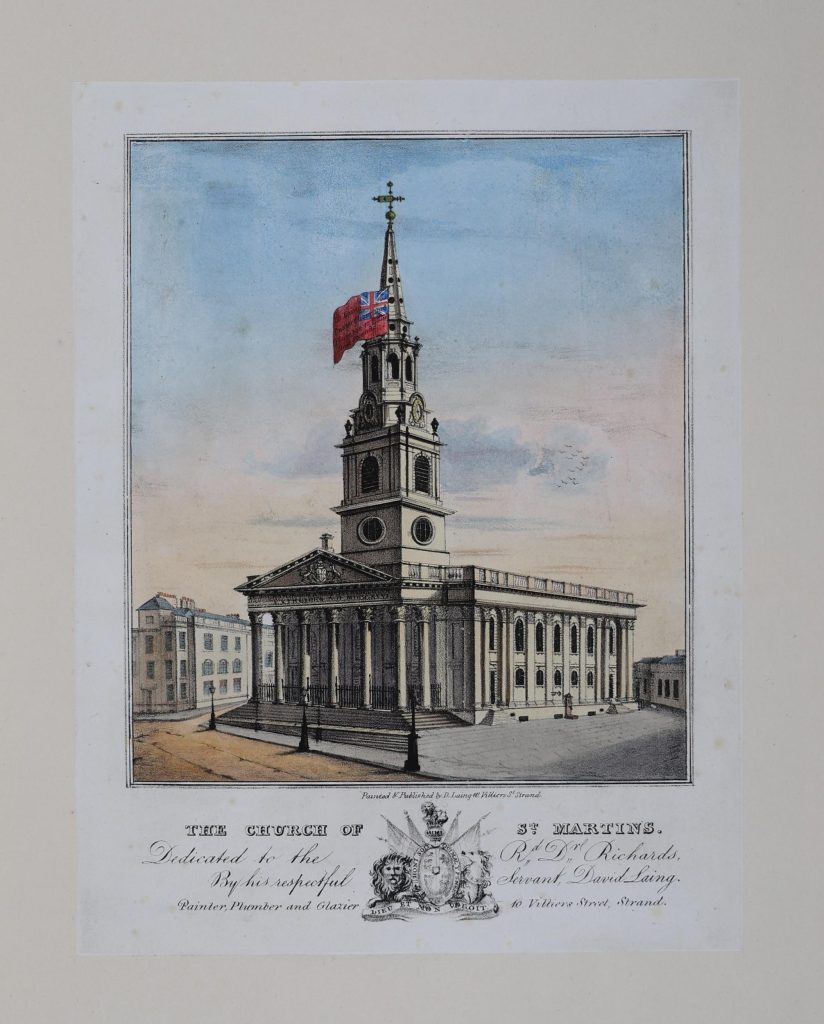

The new church when built looked across to the Royal Mews, however after the construction of Trafalgar Square, the church took on a whole new status as a key landmark at the north east corner of Trafalgar Square, as seen in this 1836 print (© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.):

One print of the church shows a large flag being displayed alongside the steeple. Flag flying from churches seems to have been a common event in the 18th and 19th centuries, and a news paper report from the 4th of June 1726 reads that “The Right Hon. The Lords of the Admiralty have made a present to the Parish of St Martin in the Fields of the Royal Standard, who have a right, it being his Majesty’s Parish, to put out the Ensign (upon all days that flags are put out) upon their Church” – although the flag in the print is not the Royal Standard (© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.):

A 1920s view looking across to St Martin in the Fields from the National Gallery:

It is difficult to photograph the interior of the church as there are very many services, musical events and rehearsals, and when these take place there are signs up saying absolutely no photography.

On my fifth recent visit, I did find a time when there were nothing was happening, so managed to get the following photo of the interior of the church:

The large number of side windows on two levels provide a significant amount of natural light into the church, and the white of the roof, walls and pillars contrasts nicely with the dark wood of the pews and the balcony seating along the side walls.

In the above photograph, there are none of the traditional monuments and plaques that we would normally expect to see on the side walls of the church. For these we have to go below ground to visit the magnificent crypt:

Originally the crypt was a place of burials, but was cleared to make a large space, which is now used for a café and event space. I will come onto the burials and crypts later in the post.

A carved sign on one of the pillars reads “The vaults and catacombs formerly containing human remains were reconstructed for temporary use as air raid shelters by the parochial church council of St Martin in the Fields jointly with the City of Westminster. A considerable part of the cost was defrayed by friends of St Martin’s both at home and abroad”:

The crypt was also used to provide refreshments to service personnel during the war. As the following from the 10th of May 1940 highlights “A team of Boys Brigade men are undertaking in turn night duty at the Services Canteen in the crypt of St Martin in the Fields Church in Trafalgar Square. Some of those who have been helping out in this way since the outbreak of war have now joined the forces themselves and there are vacancies for more Boys Brigade officers who could give an occasional night to attend to the needs of the soldiers, sailors and airmen who throng St Martins. The hours of duty are from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. and one’s turn comes about once a month”.

The church did suffer some bomb damage in November 1940.

Towards the front of the church is a small space:

And to the side of this space, there is a corridor which contains many of the memorials and monuments that were once found across the church, many of which must come from the original church as they predate the current St Martin’s:

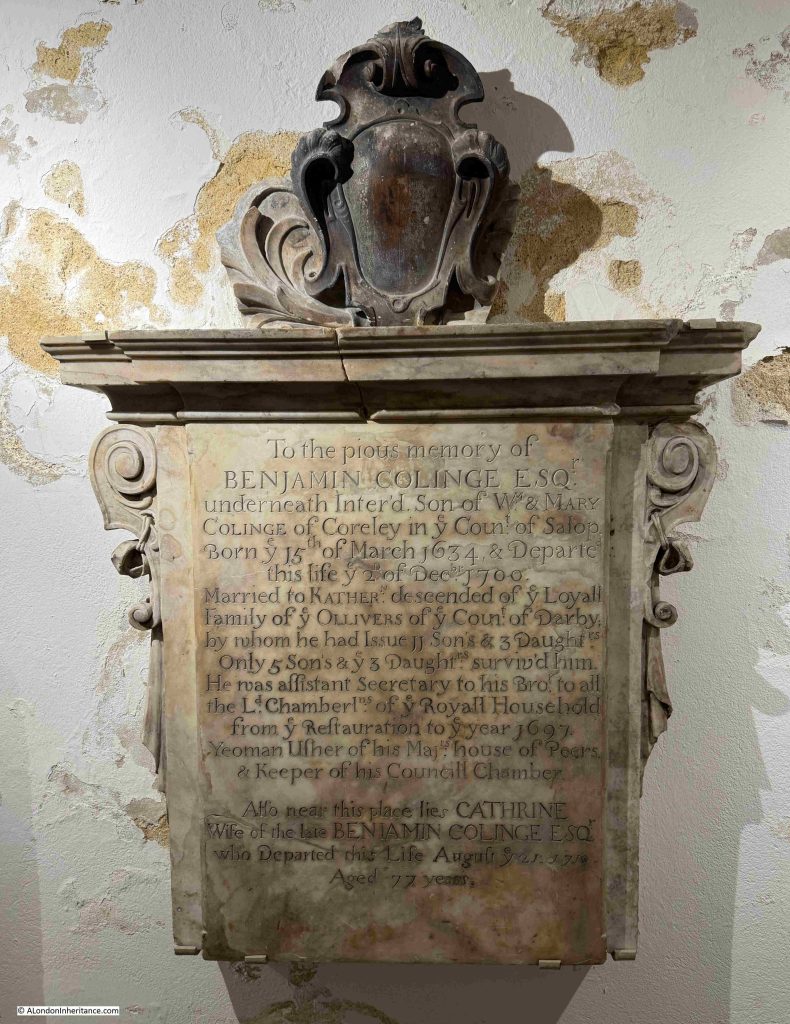

The memorial to Benjamin Colinge who died on the 2nd of December 1700, and who worked in the Royal Household from the Restoration until 1697:

With his wife Katherine (also spelt Catherine on the same memorial). They had 11 sons and 3 daughters, of which only 5 sons and 3 daughters survived their father. Katherine lived to the age of 77 – quite an achievement in the late 17th / early 18th century after having a total of 14 children.

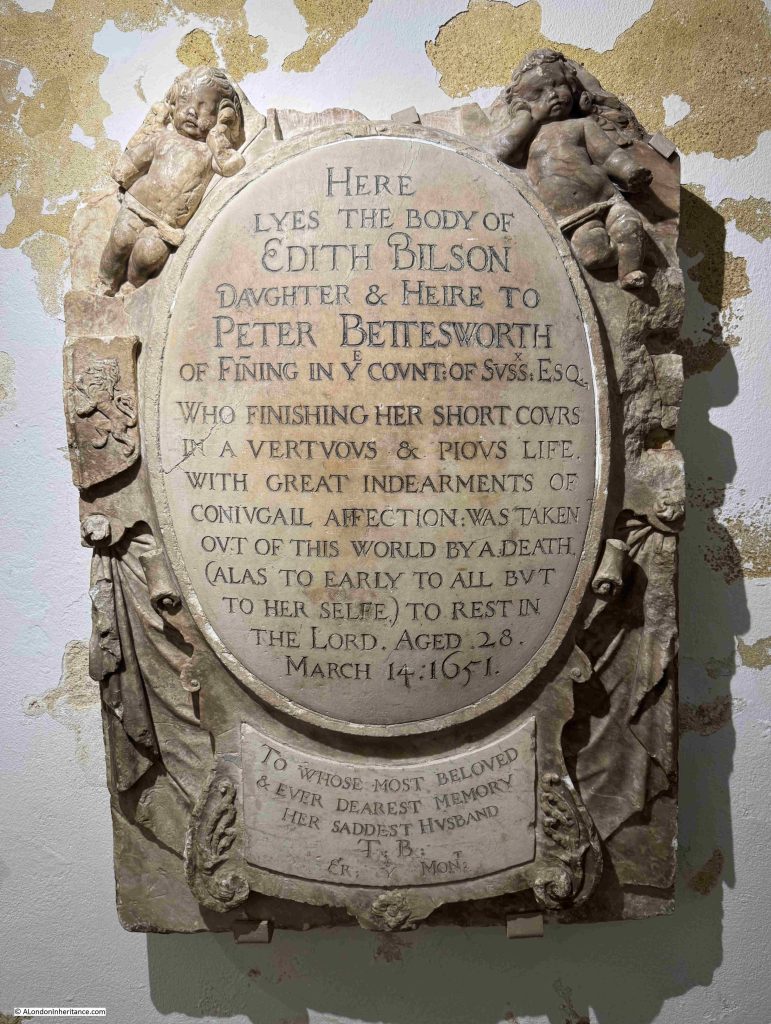

To the Pious Memory of Edith Bilson who died on the 14th of March 1651, aged 28:

There are also a few Coats of Arms, presumably of those who had been buried in the church and possibly the only parts remaining of their monument / tomb:

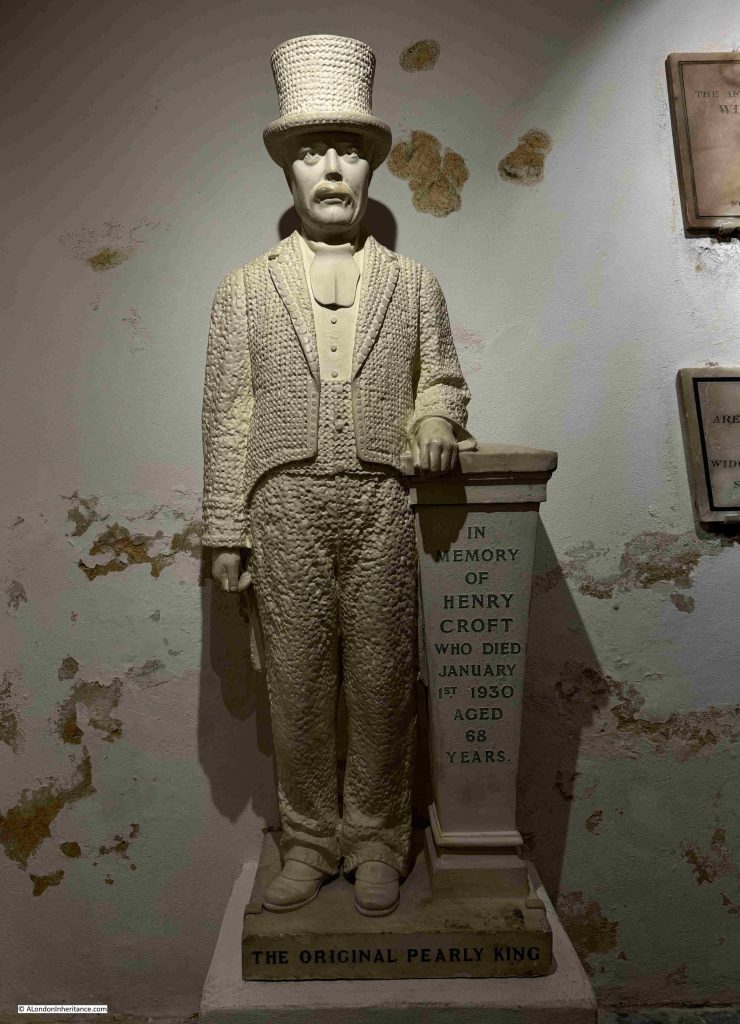

At the corner of the corridor of memorials is that of Henry Croft – “The Original Pearly King”:

Henry died on the 1st of January 1930 and there were numerous accounts of his life and funeral in the papers, with the following from the St Pancras Gazette on the 10th of January 1930:

“At the age of 67, the death took place, as the bells were ringing in the New Year, of Mr. Henry Croft, the original ‘Pearly King’. Mr Croft, who was well known in every quarter of London, had been an employee of the St. Pancras Vestry and Borough Council for over 40 years and only recently retired on pension.

Most remarkable scenes were witnessed on Tuesday, when the funeral took place to St. Pancras Cemetery. Hours before it was due to leave great crowds began to assemble round 16 Charles-street, Euston-road, and those crowds grew until all the adjoining neighbourhood was one solid mass of humanity.

There were over one hundred ‘Pearly Kings and Queens’ to say nothing of ‘Pearly Children’ who assembled in their full regalia to pay their respects to their old comrade, a man who had collected many thousands of pounds for the various hospitals of London.

Almost every Saturday and Sunday he devoted to his task, and hospitals have certainly lost a very great friend by his death. It took a number of mounted and foot police to control the crowds and it was a most impressive sight when the procession left Charles-street to wend its way to the cemetery, led by a band of pipers playing a haunting lament, and many banners were displayed by members of the various societies and organisations with which the deceased was connected. The coffin was borne by four comrades – all Pearly Kings – and on it rested the deceased tall hat of pearl buttons, and also all the medals with which he had been presented for his charitable work, displayed on a black velvet cushion.

The coffin was drawn in an open car with four horses, and the three coaches following contained his widow and family – he had two sons and three daughters. Behind the mourning coaches came a stream of vehicles of all kinds carrying other Pearly Kings and Queens and a whole retinue of the deceased friends. The procession was nearly half a mile in length and was one of the largest that London has seen for many years.”

The statue of Henry Croft was originally installed where he was buried in St Pancras Cemetery, however after several instances of vandalism, it was restored and moved to the crypt in 2002. The choice of St Martin in the Fields was because of the long association of Pearly Kings and Queens with the church, and it is where they continue to hold their Annual Harvest Festival.

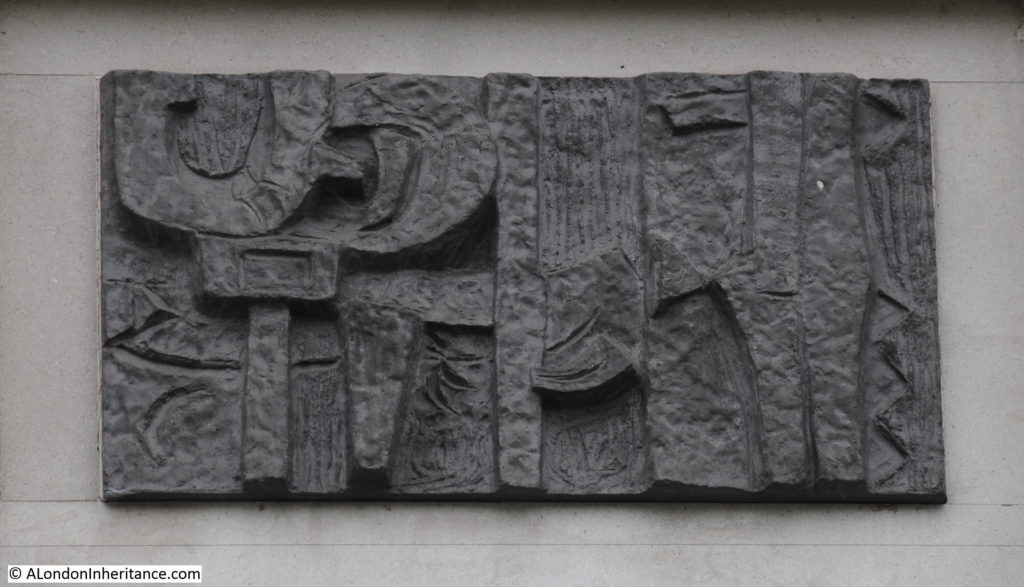

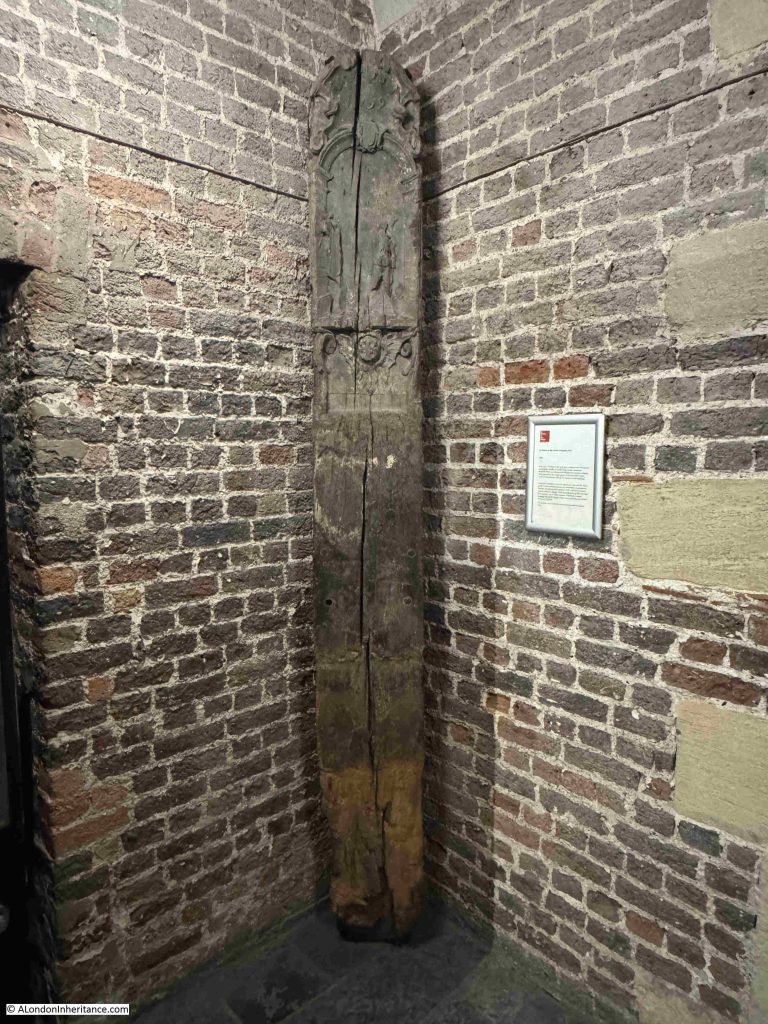

On display in the crypt is a reminder of the barbaric forms of punishment that offenders could suffer in London – the St Martin in the Fields Whipping Post:

There were a number of whipping posts across London, and these were often associated with a pillory. Whipping was also carried out with the offender tied to a cart, and whipped as they were being moved between two places, often relevant to their crimes.

Whipping was a public punishment, aimed not only at punishing and humiliating the offender, but also visibly showing the public the type of punishment they would suffer if they were to commit similar crimes.

The punishment was also a risky time for the authorities, if the general public was not happy that the offender was being given a fair punishment, or if there were other general issues with authority. For example, the whipping of James Dinord, a journeyman weaver in Bethnal Green in 1829 was attended by the officers of Worship Street, Lambeth Street, the Thames police and all the parochial and special constables of the district, including the parochial officers of the twenty one districts of Tower Hamlets, due to the risk of trouble.

The large crowd was described as being silent whilst the punishment was carried out, with not a single murmur being heard, nor the slightest symptom of riot or insubordination.

The impact of a whipping or being confined in the pillory could also effectively be a death sentence. On the 28th of September 1810, the London Statesman reported that “The sheriffs and Jack Ketch were actively employed yesterday between the pillory and the whipping post in the Old Bailey; their respective functions were not finished till it was nearly dark. Viguers, the miscreant placed in the pillory in Cornhill, is at present blind, in consequence of the pelting he received. He was so much bruised and lacerated, that he is not expected to survive”.

I cannot find where the St Martin in the Fields Whipping Post was originally located. I wonder if it was a short distance further south at Charing Cross which would have been a public place, at the junction of key roads, for such a public punishment to be carried out.

The Whipping Post dates from 1752, as indicated by the year carved at the top of the post, and at this time St Martin was relatively enclosed within streets and buildings, long before Trafalgar Square was built, and whilst St Martins Lane was a busy street, it would not have been such a public location as the main street just to he south:

It is interesting that it was thought necessary that the post used for such a punishment should also be ornately carved, it was probably to give some authority to the whipping post and the punishments carried out.

There was a pillory at Charing Cross, as illustrated in this print from 1809, by Rowlandson and Pugin from Ackermann’s Microcosm of London:

There is a large space space to the left side of the church and to the rear. This space was once part of the burying ground, which originally extended further than the space we see today:

There were up to 70,000 burials in the crypt and across the burying ground and between 1827 and 1830 the burying ground was emptied and the crypt space extended under a programme of work by John Nash to create buildings to the north of the church. This also allowed Duncannon Street which now runs along the southern edge of the church to be built.

Al the crypt space was finally emptied between 1915 and 1937.

The area to the north and south of the church has been significantly renewed, with a couple of floors of space developed below ground, consisting of the church hall, music rehearsal room, a chapel, open space, and a shop.

There is a new entrance to the crypt and below ground space, as shown in the photo above and just behind the entrance there is a light well that lets natural light into the two floors below:

Looking down through the light well:

The church seen from the north east showing space to the side and behind the church which was once part of the burying ground, and then the below ground extension to the crypt:

And from Duncannon Street, the street created when the burying ground to this side of the church was emptied of human remains:

Today, as well as church services, St Martin’s is a centre for music with regular concerts, and the original home of the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, formed in 1958 by Sir Neville Marriner, and who had their first performance in the church in November 1959.

There is an interesting video by Eric Parry Architects on the project to redevelop the below ground space:

St Martin in the Fields is a very impressive church. It is ideally placed at the north east corner of Trafalgar Square, a space that would not be developed for over 100 years after James Gibbs designed the church, and modified the front to enlarge the portico during the construction process, a change which just adds to the view of the church as you look across Trafalgar Square.

I suspect he would be rather pleased with the views now available of his church.

Resources – Historical maps of Southwark and City Ward Maps

In this months section on resources that may be of help with researching the history or London, I am looking at some more maps.

Maps are brilliant resources for understanding the history of an area, and by using maps of different dates, how an area has developed over the years.

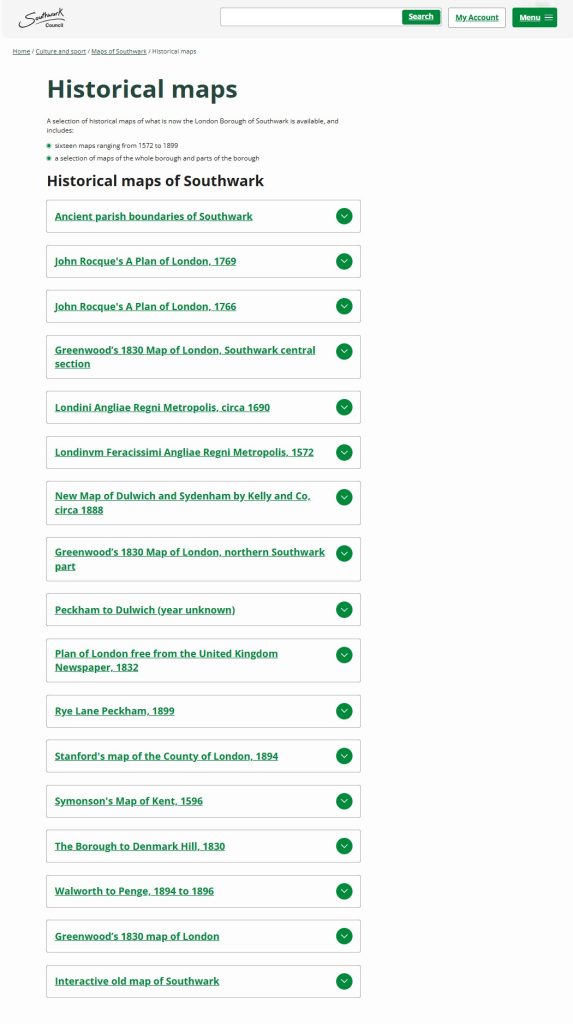

Southwark Council have put a range of historical maps online. The title of the respective webpage is Historical maps of Southwark, although the maps available cover much more than just the Borough of Southwark, with many of the maps showing the whole of London.

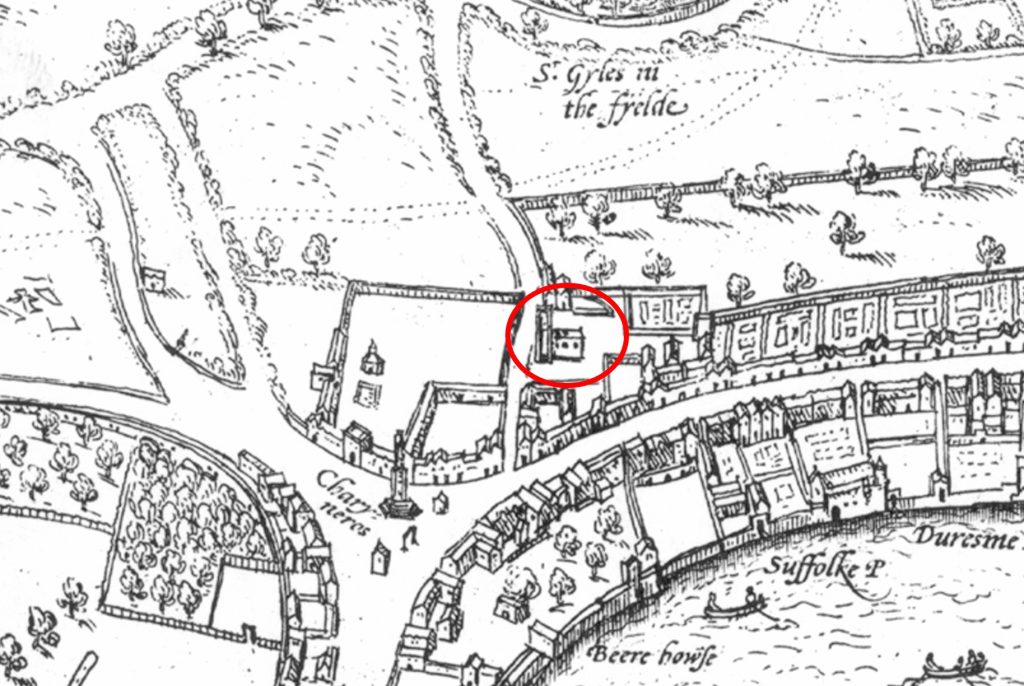

The list shows the range of maps available, and to give an example, the following is an extract from the 1572 map Londinvm Feracissimi Angliae Regni Metropolis, and in the extract I have put a circle around the main subject of the post – St Martin in the Fields:

The map shows how the church justified the use of “in the Fields” within the name, as at the time, it was on the edge of the built city. An early St Martin’s Lane can be seen running north in front of the church.

To the south is the Strand, which runs to Charing Cross, then continues to the south to Westminster. The importance of the Strand can be seen by the large houses running along the street, with rear gardens leading down to the Thames, where each house would typically have its own Watergate.

To the north of the church there are fields, up to another “in the Fields” church, St Giles in the Fields.

At the major road junction at Charing Cross, we can see the last of the Eleanor Crosses, which marked the route taken by the body of Eleanor of Castile, the wife of Edward I, from the location of her death in Lincolnshire, to her burial at Westminster Abbey.

It was taken down on the orders of Parliament in 1647, and the stones were allegedly used in various building works in Whitehall.

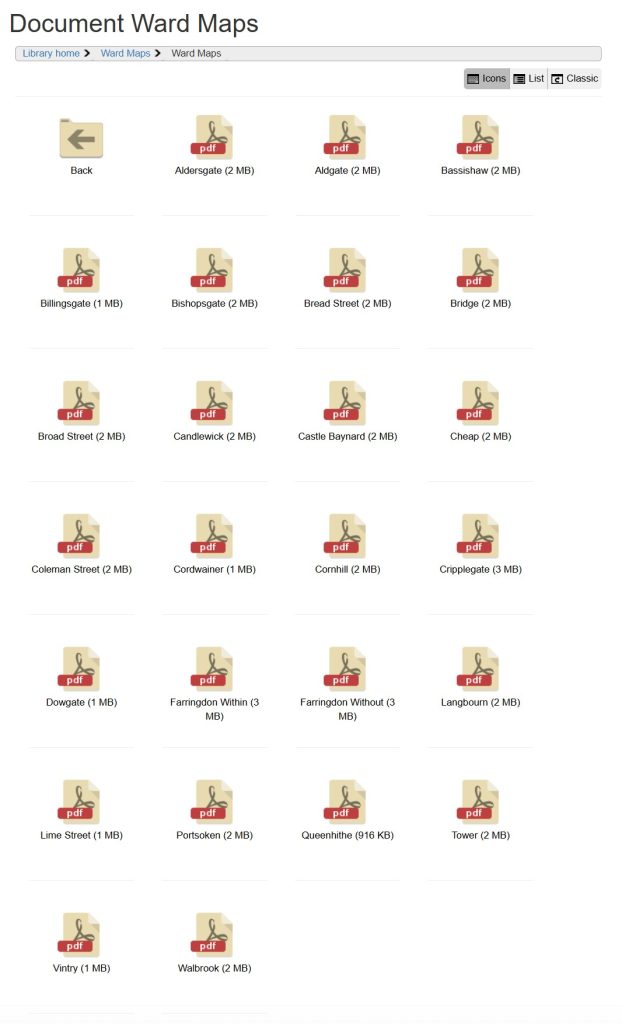

Another London local authority with some interesting maps is the City of London Corporation. If you have ever wondered about the current boundaries of all the City Wards, then the Corporation have a webpage to help.

The Ward Maps webpage can be found by clicking here, where you will find subfolders for each of the City Wards, as shown in the following image:

Clicking on any of the Wards when you are on their webpage, will bring up a PDF map showing the boundaries of the relevant Ward superimposed on a modern day street map.

Each Ward Map also shows the boundaries of the City of London, along with the adjacent Wards.

Both the Southwark and the City of London Corporation webpages provide very different views of London, but both help provide an understanding of the historical development of the city, and how historical boundaries still apply in a very modern City.