Battersea Power Station is one of London’s most well known industrial landmarks. The first phase of the power station was completed in 1933 and the station finally stopped generating electricity in 1983.

Since then, the majority of the building has been left a shell, preserved due to being a grade 2 listed building and the subject of various schemes for rebuilding and regeneration of the area.

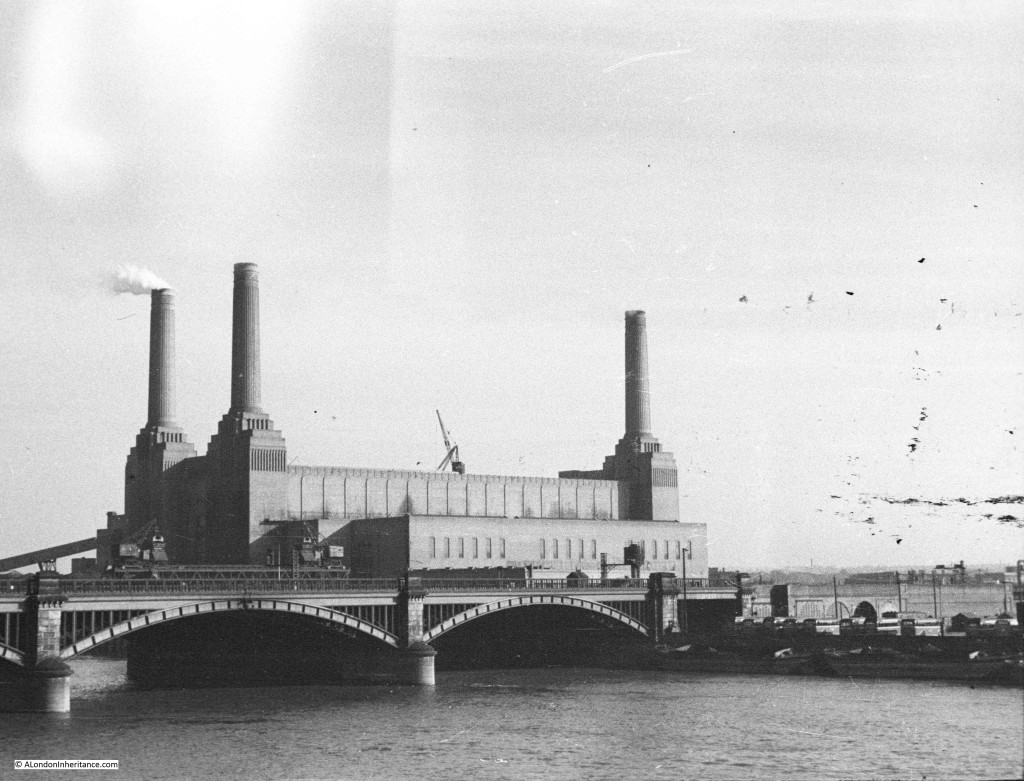

My father took the following photo of the power station from the north bank of the Thames, in the very early 1950’s when three-quarters of the building was complete.

When the photo was taken, the power station only had three chimneys. Power stations are frequently built using a modular approach so that the site can start generating electricity as soon as possible and capacity added when there is sufficient demand and an economic justification. This approach was used in the 1930’s and continues to this day.

Battersea “A”, the first phase of the power station consisted of the right hand side of the building as seen from the north bank. Construction of this part of the building started in 1929 and the station was operational soon after the Sir Giles Gilbert Scott brick exterior work was finished in 1933.

Battersea “B”, the left side of the building commenced in 1944 with the fourth chimney completed in 1955 when the power station reached the configuration that was to last until closure.

There have been many failed scheme to reconstruct the building since closure, however work finally started last year, so before there was too much change, last summer I took a walk along the north bank of the Thames to take some photos from the same position as my father’s original.

There is about 62 years between the two photos and although the power station is now only a shell of the original, the overall impression of the site is of very little change in the intervening years. The first crane has arrived on site and the very early stages of work has commenced on the building. The site will soon change dramatically.

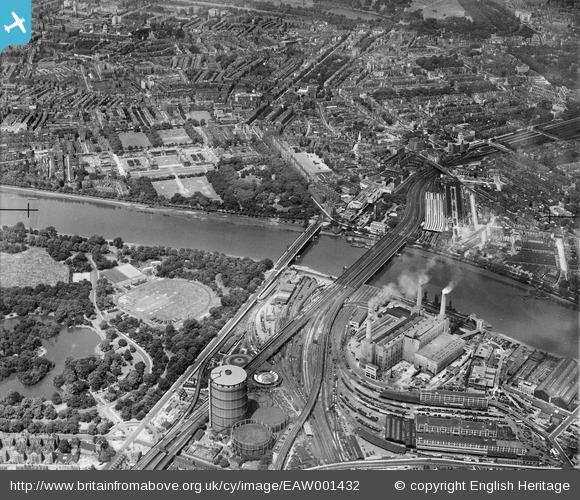

The gas holder in the background in both the original and later photos is nearly 300 feet high and 180 feet across and could hold seven million cubic feet of gas.

I recently found another photo my father took, probably on the same day. This was at the very end of a strip of negatives and has some damage to the edge which caused a problem with scanning but I finally managed to scan the following:

This photo was taken from the north end of Chelsea Bridge and very clearly shows the three chimneys, with a crane at the far corner, probably engaged in the construction of the remaining part of Battersea “B”.

This year, I took the following from the same position as my father’s original photo, which also shows how work has rapidly increased since the summer of last year.

Following publication of this post, I received the following from Adrian Prockter who runs the “knowyourlondon” blog:

“Only three chimneys were required because there were only three boilers underneath. The fourth chimney was added purely for decoration and, probably more importantly, to provide an even weight distribution for the building. Because it is built on clay, a symmetrical shape will provide an even pressure across the foundations”

Which answers why in all the photos I have seen of Battersea in operation, I have not seen one with smoke from the fourth chimney.

Battersea power Station is now a major construction site. One of the first major changes being the removal of the chimney on the corner of the building to the right of the photo. The level of corrosion and cracking on the original chimneys was such that they were considered unsafe without major work. Apparently the only way to deal with this was to dismantle the original chimneys and then rebuild to the same designs. Unfortunately when the building is complete they will not be the original chimneys, but at least the overall appearance of the building with a chimney at each corner will be the same.

Battersea Power Station was photographed from the air by Aerofilms during the period the building evolved from the initial configuration with two chimneys through to the final four chimneys. The following photo was taken in 1946 and clearly shows the three chimneys in operation with a space in the lower quarter where the final generating unit and chimney would soon be added to complete the building.

This Aerofilms image taken in 1952 shows the main building nearing completion with only the fourth chimney to be added. My father’s photo’s would have been taken at around the same time.

I have no idea whether there is any truth in this, but one of the stories my father told me as a child was that when construction of the building was on-going during the 1930s and tensions with Germany were on the rise, there were rumours in London that the chimneys were actually very large guns. The fact that the chimneys point straight up so would not have been very effective as guns does not seen to have been considered. No idea whether this is true, but a nice story.

The following photo is of the cranes on the edge of the river that were used to unload coal from barges on the river to conveyor belts that moved the coal to storage areas ready to be burnt.

As well as above ground storage, the power station also had a sunken storage area adjacent to the river. This was almost 200 yards long and was able to store 75,000 tons of coal.

The cranes ran on rails and could move along the river edge to the location of the waiting barge. The current cranes are from the 1950s, replacing the original cranes from the 1930s. These cranes are also grade 2 listed and will be retained.

As well as the external appearance, Battersea Power Station had a number of other very unique features.

The power station had a gas-washing plant. This was able to remove more than 90 per cent of the sulphur in the smoke emitted during operation. The plumes of smoke were white rather than the very dark smoke from other earlier power stations. A very key benefit given the problems that London was experiencing at the time with air pollution.

Another unique feature of the power station improved the living conditions of people on the north bank of the river. The Churchill Gardens housing estate is opposite the power station and is heated by the power station. The Pimlico District Heating Undertaking implemented a system whereby exhaust steam from two turbines in the power station was used to heat water to 200 degrees Fahrenheit. It was then pumped under the river to a storage system on the north bank where it heated water in the residential supply before being circulated back to the power station. For the time, a very unique combined heat and power system.

The weather when I took my first Battersea photo last summer was excellent so a walk back along the north bank of the river into central London was a very easy decision. There are a number of interesting locations along the short stretch to Vauxhall Bridge.

The first is the lovely Pimlico Gardens between the Grosvenor Road and the river.

At one end of the gardens is a statue to William Huskisson, a member for parliament but unfortunately also one of the first to be killed in a railway accident.

From “The Face of London” by Harold Clunn:

“Huskisson was killed by a locomotive at the ceremonial opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway on 15 September 1830. The procession of trains had left Liverpool, and at Parkside, the engines stopped for water. Contrary to instructions, the travellers left the carriages and stood upon the permanent way. Huskisson wanted to speak to the Duke of Wellington, and at that moment several engines were seen approaching along the rails between which he was standing. Everybody else made for the carriages, but Huskisson, who was slightly lame, fell back on the rails in front of the locomotive Dart, which ran over his leg; he was carried to hospital, where he died the same evening.”

After such a terrible end, Huskisson now quietly watches over Pimlico Gardens:

Pimlico’s river front was not always so calm. From “The Trip down the Thames by the Victoria Steamboat Association’s Steamers, 1893”:

“Pimlico, once noted for its public gardens. Among them was ‘Jenny’s Whim’ a summer resort of the lower classes, where duck hunting, bull-baiting and al fresco dancing were the order of the day”

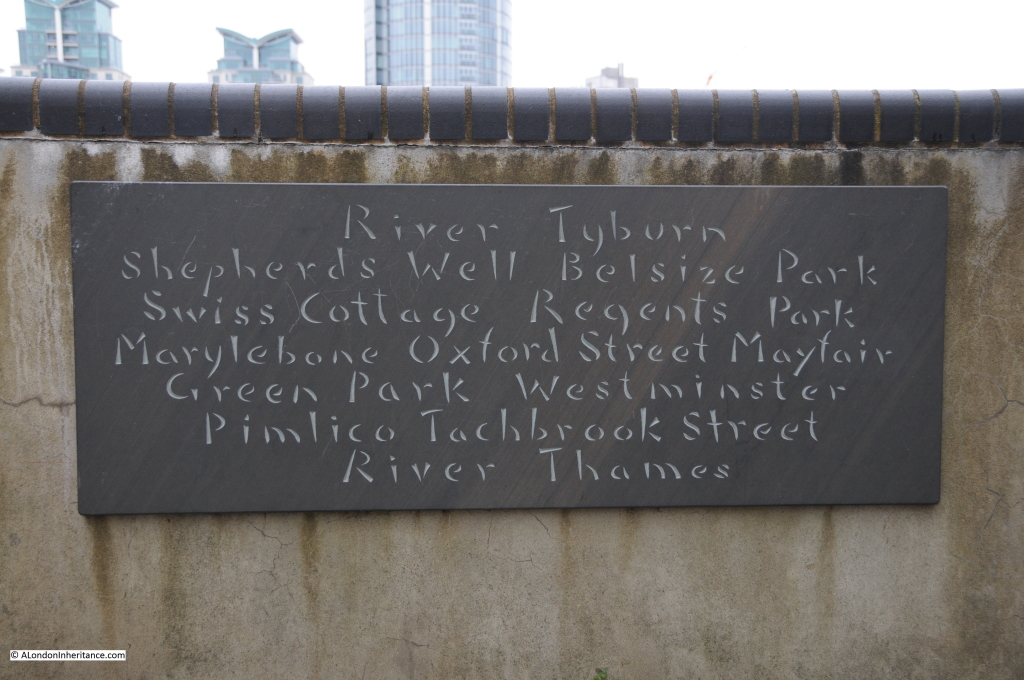

A short distance on, the River Tyburn reaches the Thames as recorded by the following plaque on the Thames Path which records the route of the river:

If we walk on a short distance and walk along Vauxhall Bridge, and providing the tide is low, the Tyburn outflow tunnel is very visible:

From Vauxhall Bridge we can also look back at the sweep of the river and the power station. This will look very different in a few years time. The south bank of the river from the end of Vauxhall Bridge to Battersea Power Station is currently under a frenzy of building with the new American Embassy and a large number of flats / apartment buildings all of which are probably outside the financial reach of the majority of Londoners.

The first Vauxhall Bridge was built in 1811-16. The current bridge was opened in 1906 and the most interesting features of the bridge are not visible when crossing over the river. The following photo shows the eastern side of the bridge. Above each of the granite piers is a colossal bronze statue, four on each side of the bridge. The statues were by Alfred Drury and F.W. Pomeroy and are of draped women representing the Arts and Sciences. They were added to the bridge in 1907.

On the eastern, downstream side of the bridge are Drury’s statues representing Science, Fine Arts, Local Government and Education:

On the western, upstream side of the bridge are Pomeroy’s statues representing Agriculture, Architecture, Engineering and Pottery:

Each statue weighs roughly two tons and as can be seen from the above photos are very detailed. It is a shame that these probably go unnoticed by the majority of people travelling across and around Vauxhall Bridge.

The sources I used to research this post are:

- Arthur Mee’s London (A complete record of London as it was before the bombing) published in 1960

- The Face of London by Harold Clunn 1970 reprint

- Lure and Lore of London’s River by A.G. Linney