For this week’s post, I am in Queen Square, Bloomsbury tracking down the location of the water pump that my father photographed in 1947;

The view from the same position 70 years later:

The cast iron fountain dates from 1840 (although the lamp at the top is of a later date). On the base of the water pump on both sides are the coats of arms of St. Andrew and St. George. The strange white and black symbol half way up is a temporary survey marker.

The above view is looking west towards the church of St. George’s Holborn and in the photo below looking east towards where Great Ormond Street meets Queen Square:

The fountain is surrounded by four bollards, three of Portland Stone and one of cast iron – no idea why there is this single iron bollard. The same set of bollards appear in the 1947 photo. I wonder if the single cast iron bollard is original being of the same material as the fountain and the stone bollards are latter replacements following damage to the other three cast iron bollards?

The water pump sits within a large paved area at the southern end of Queen Square with the gardens running north and occupying the majority of the centre of the square.

Construction of Queen Square started in around 1706. The square was built on the gardens of Sir Nathaniel Curzon’s house, which was typical of the expansion of London in this area with new houses and squares taking over the from the large houses that were once surrounded by countryside. The square was completed by 1725 but buildings only occupied three sides, the northern side was left empty so that the inhabitants of the square could enjoy the views over open countryside to the hills of Hampstead.

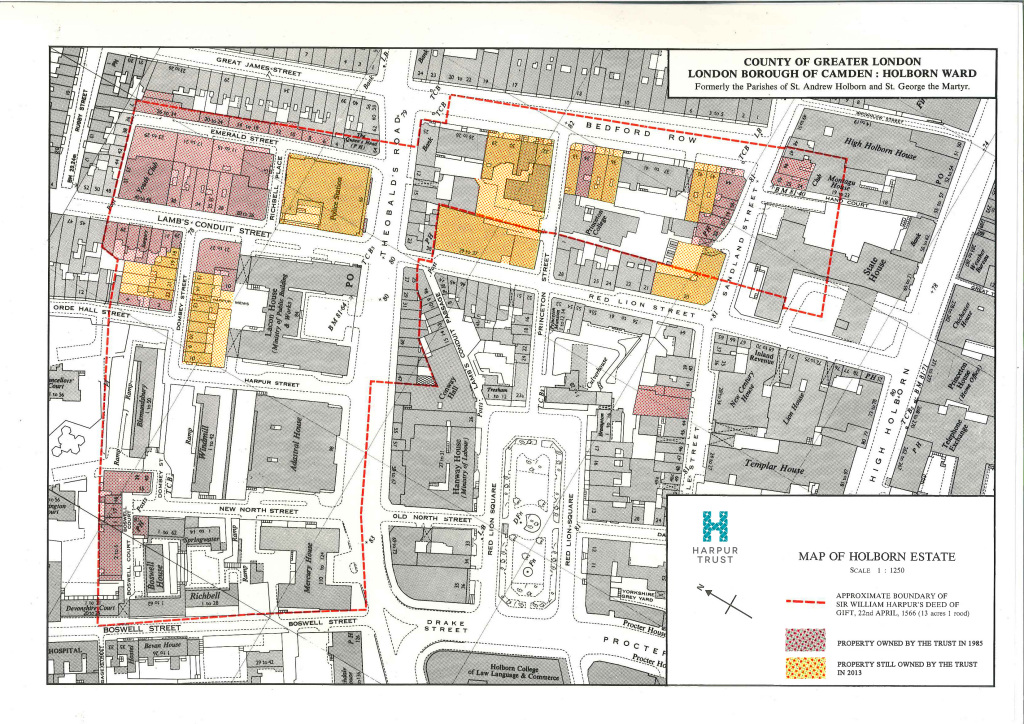

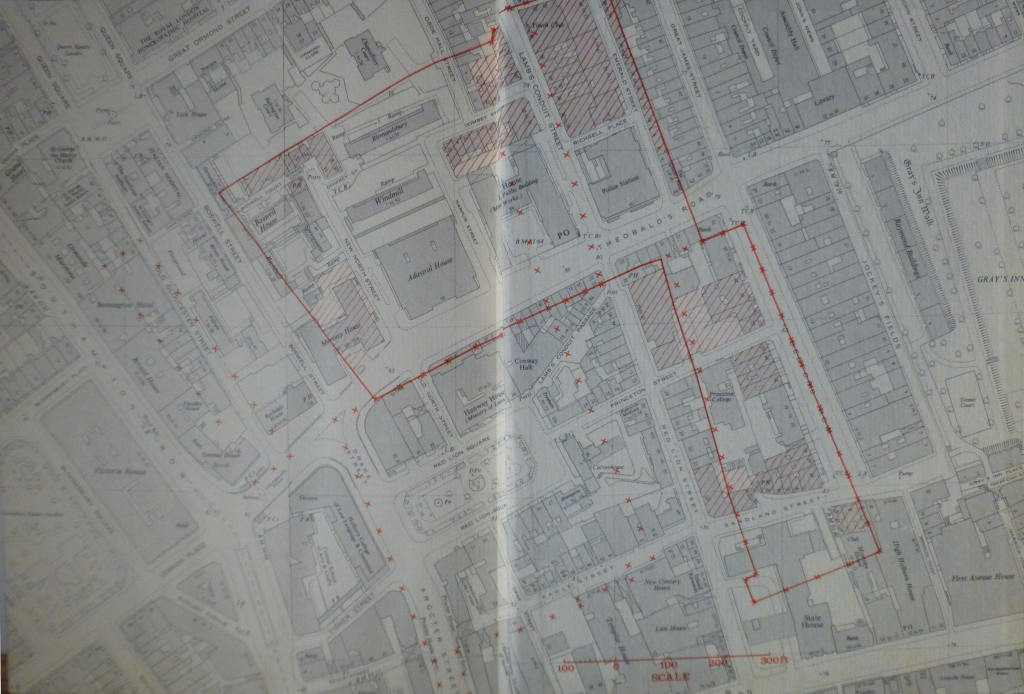

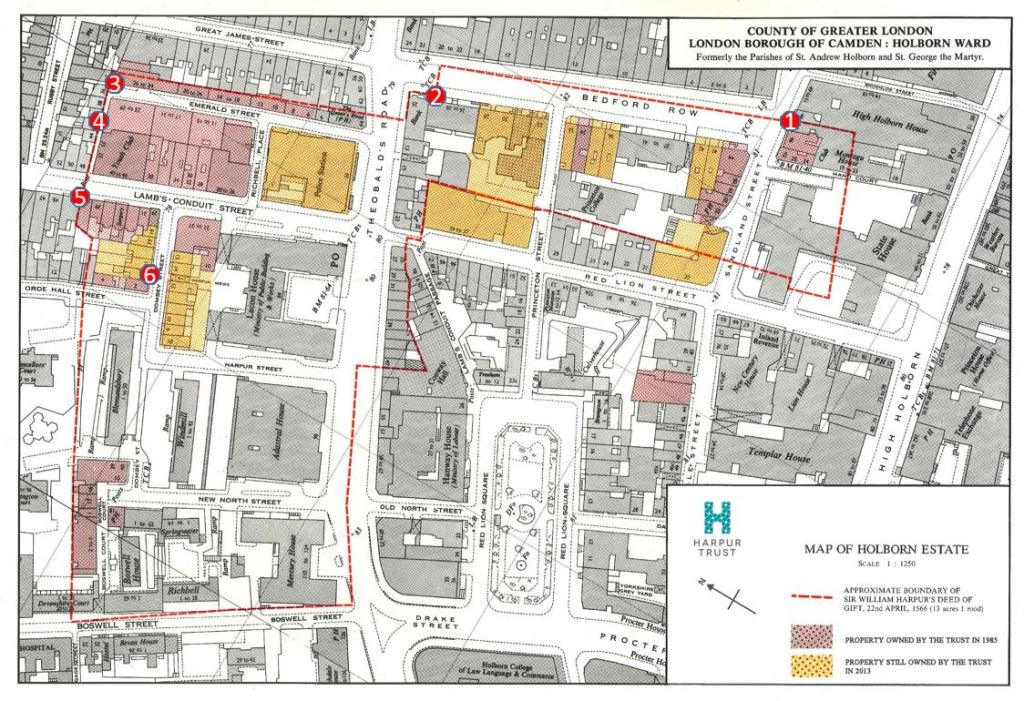

The following extract from John Rocque’s map of 1746 shows Queen Square in the centre, just below the line formed by the page fold. All the land to the north of the square is still open country. The map indicates that at the northern end of the square there were some ornamental gardens and trees to provide a boundary between the square and the lane running from left to right named Powis Wells in the map, this would later become Guildford Street.

The map also shows that in 1746, gardens occupied the centre of the square north from the junction with Great Ormond Street with the large paved area occupying the southern end of the square as it does today.

Behind the water pump in my father’s photo are two buildings of very different style. The same buildings remain to this day as shown by my photo, although they are now somewhat obscured by the trees that have grown around the water pump.

The building on the left has a rather large and ornate coat of arms above the door and along the width of the building, below the top floor windows, is written “The Italian Hospital”.

The Italian Hospital dates from 1884 when it was founded by the local Italian businessman Giovanni Batista Ortelli to provide medical care for sick Italians living in London who could not afford to pay for health care. It originally started operation in Giovanni’s home in Queen Square but moved into the purpose built building shown above following construction in 1898 to 1899.

It closed in 1990, but is now part of Great Ormond Street Hospital.

The buildings on the right are two Georgian houses that are now occupied by the Mary Ward Centre. Although there have been considerable changes to these two buildings, they are some of the few remaining original buildings with the first lease being granted on the 19th June 1703 by Sir Nathaniel Curzon.

At the junction of Queen Square and Old Gloucester Street is the St. George the Martyr Parochial School. Built in 1877 as a church school aligned with the adjacent church. The school has long closed and the building appears locked and empty. Just to the rear of the building on the top floor can be seen the metal frame of the meshed cover over an outside playground – the only way to provide outside play areas at inner city schools.

The plaque on the corner of the building records the year of opening and also that the school was for 200 boys.

Next to the school and in the south west corner of Queen Square is the church of St. George, one of the first buildings on the square The church dates from 1706, its construction having been funded by some of the wealthy inhabitants of the new square.

There was no space available for a graveyard adjacent to the church, this was instead provided in the land just to the north of the Foundling Hospital and is marked on the Rocque map shown above.

The antiquarian Dr. William Stukeley was rector of St. George from 1747 until his death in 1765. It was Stukeley who popularised the association of Stonehenge and Druids and in Old and New London, Edward Walford records Stukeley as also being known as the “arch druid”. For some reason, he had requested to be buried in East Ham rather than the burial ground of the church of which he was rector.

Opposite the church and to the right of the above photo is another of the original buildings. This is the pub “The Queens Larder”. The building now occupied by the pub was first let by Sir Nathaniel Curzon to Matthew Allam, a stationer.

George III stayed in Queen Square whilst under the care of a Dr. Willis whilst he was suffering from the mental illness that would impact so much of the later years of his reign. Queen Charlotte would apparently store the food that the King preferred in the cellar underneath the building which gave the pub its name during the King’s reign.

Although Queen Square is built with houses on three sides which were occupied by the business and professional classes who could afford homes on the edge of the city with the benefits of the countryside and clean air, during the 19th century the square and many of the surrounding streets were rapidly occupied with charities and medical institutions which resulted in rebuilding of much of the square.

Old and New London provides some background to the institutions that occupied the square in the years leading up to publication:

“Queen Square, as well as Great Ormond Street which we shall shortly pass, seems to be a favourite centre of charitable institutions. At the corner of Brunswick Row is the Hospital for Hip Diseases in Childhood, which was founded in 1867. At No. 22 was for many years located the oldest of Ladies’ Charitable Schools. This institution, for although called a school, it is in reality one of our oldest institutions, was established in 1702 for educating, clothing and maintaining the daughters of respectable parents in reduced and necessitous circumstances. The Ladies’ Charity School was removed in 1883 to new quarters in Notting Hill; and the site of the building here is being utilised in an extension of the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic, which adjoined it. This hospital was instituted in the year 1859.

At No. 29 is the College for Men and Women, with which is incorporated the Working Women’s College, both offshoots of the Working Men’s College established in 1874 with the object of supplying to men and women occupied during the day a higher education than had hitherto been within their reach.

No. 31 formed the head-quarters of some Roman Catholic charitable institutions, among which are the Aged Poor Society.

A large double house on the south side of the square is the College of Preceptors, founded in 1846, its object is to afford to commercial and other public and private schools those tests of results which were afforded to other schools by the university local examinations. “

This is just a sample of the institutions that were operating in the area in the later half of the 19th century. These also included the London Hospital for Sick Children which opened on the 2nd of January 1852. The hospital is today better known as Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Plaque above one of the entrances into the central gardens:

Inside the gardens, the following view is looking south towards the location of the water pump. The sculpture is titled “Mother and Child” and is by Patricia Finch. It was installed in the gardens in 2001 in memory of Andrew Temple Meller who was a Director of the Friends of Great Ormond Street Hospital from 1995 to 2000.

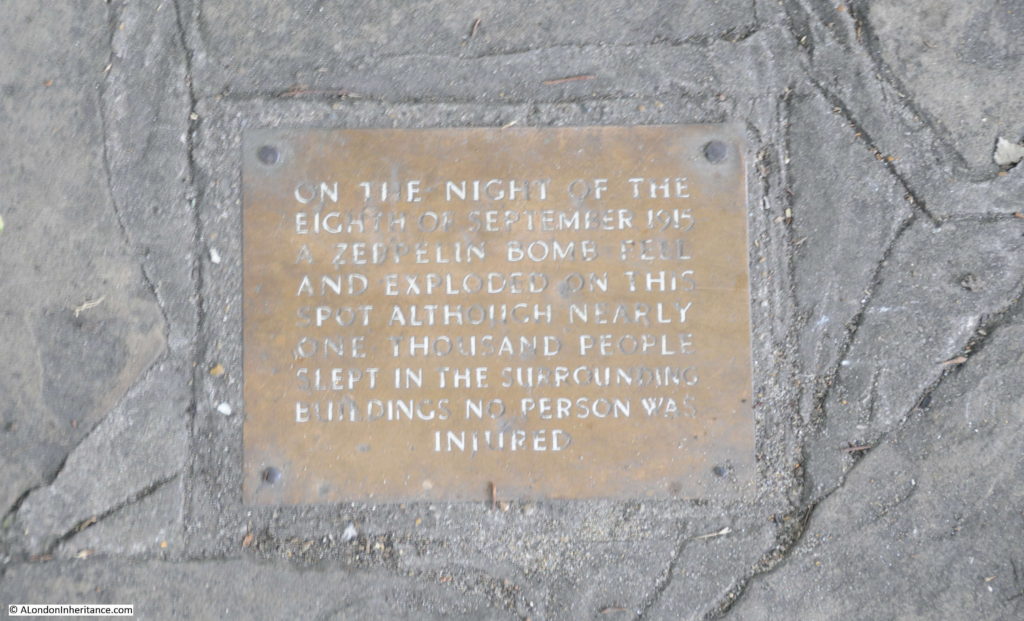

Nearby there is a plaque set into the ground that is rather easy to miss. It records the night of the 8th September 1915 when a bomb dropped by a Zeppelin fell on the location of the plaque. The Zeppelin was the L13 commanded by Heinrich Mathy. The Zeppelin’s route over the city resulted in bombs being dropped in Golders Green, close to Euston Station, Bloomsbury, Clerkenwell, Smithfield and the railway lines into Liverpool Street,

As the plaque states, there were many people asleep close to the bomb in Queen Square, but luckily there were no casualties. This was not the case at other locations as there was a death in Lambs Conduit Passage, along with deaths in Clerkenwell (four children) and in Smithfield.

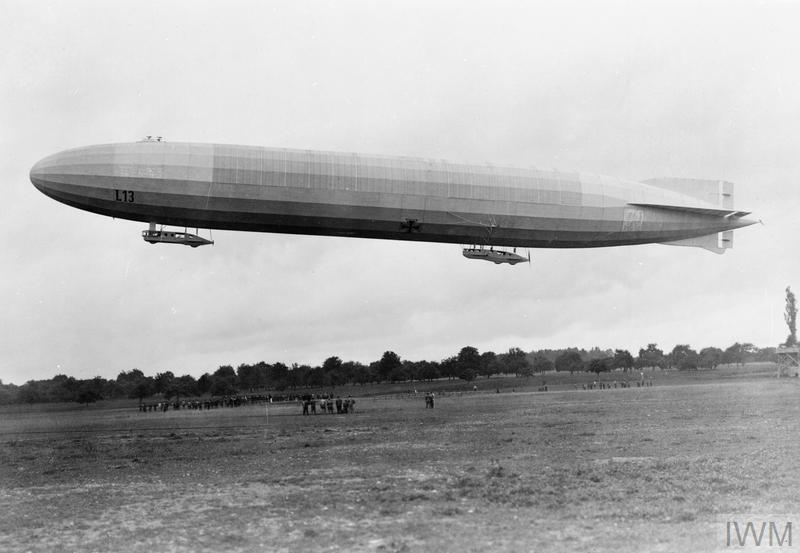

The following photo (© IWM (Q 58456)) shows the L13 Zeppelin.

The L13 was decommissioned in 1917 however Heinrich Mathy died on the 2nd October 1916 when he was commander of L31 which was shot down near Potters Bar. Mathy along with his entire crew died after jumping from the burning Zeppelin.

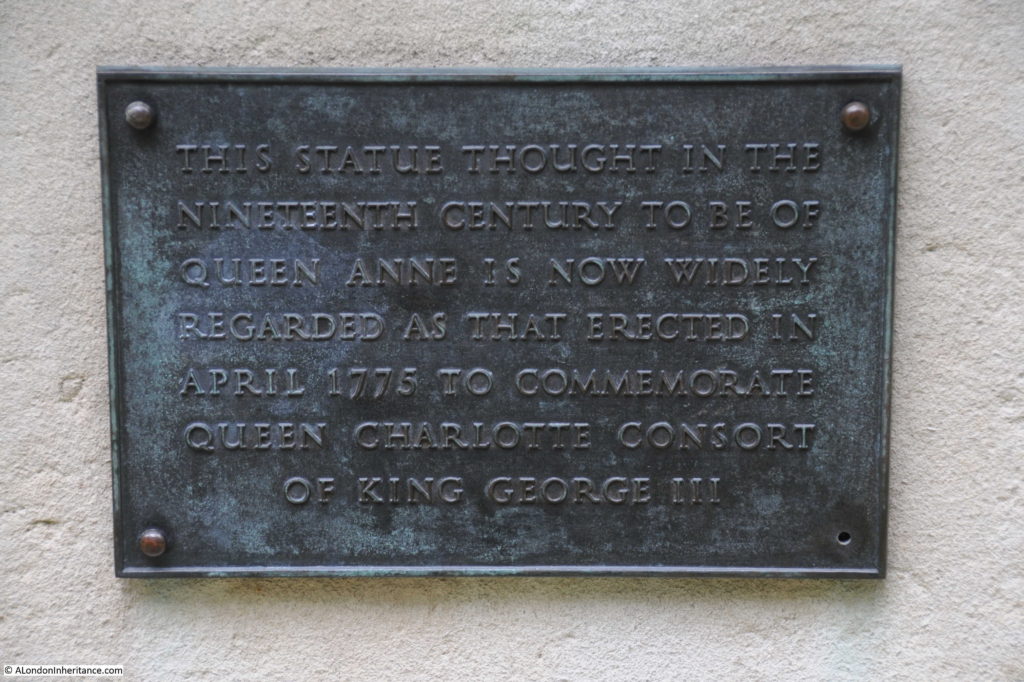

Queen Square is named after Queen Anne, the monarch at the time of the construction of the square and there is a statue at the northern end of the square which was originally thought to be have been Queen Anne however as the plaque on the pedestal (shown below) states it is now thought to be of Queen Charlotte, who was also responsible for the naming of the Queens Larder pub.

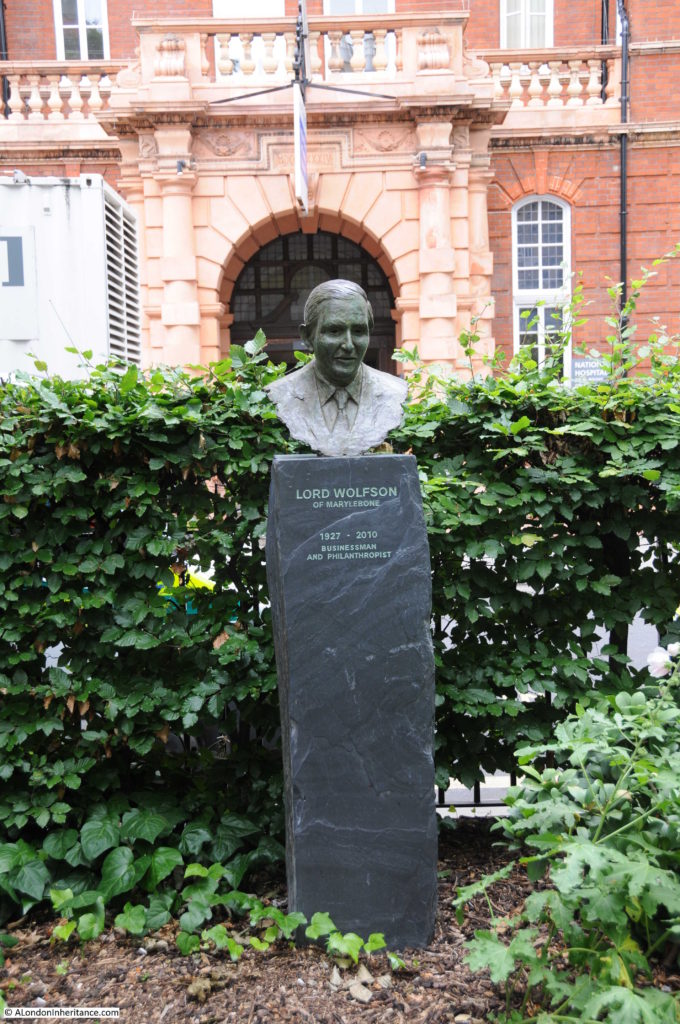

At the north eastern end of the square there is a recent statue of Lord Wolfson, the chairman of Great Universal Stores (remember them ?) and also founder with his father of the Wolfson Foundation in 1955 which was endowed with £6 million of Great Universal Stores shares.

The Wolfson Foundation is a charity that provides grants to individuals and organisations in the fields of science, health, education and the arts and humanities. I assume that the medical institutions that now surround Queen Square have benefited from the Wolfson Foundation, hence the statue.

The square dates back to the start of the 18th century, however standing at the north eastern corner it was strange to hear a 21st century sound with the rhythmic thumping of an MRI scanner working in a large container parked in the street. There are other reminders of the functions of the buildings surrounding the square. Whilst I was there, patients in wheelchairs were being pushed around the square. As well as being a historic square this is also a centre of medical research and treatment.

Along the eastern side of the square are buildings of the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery.

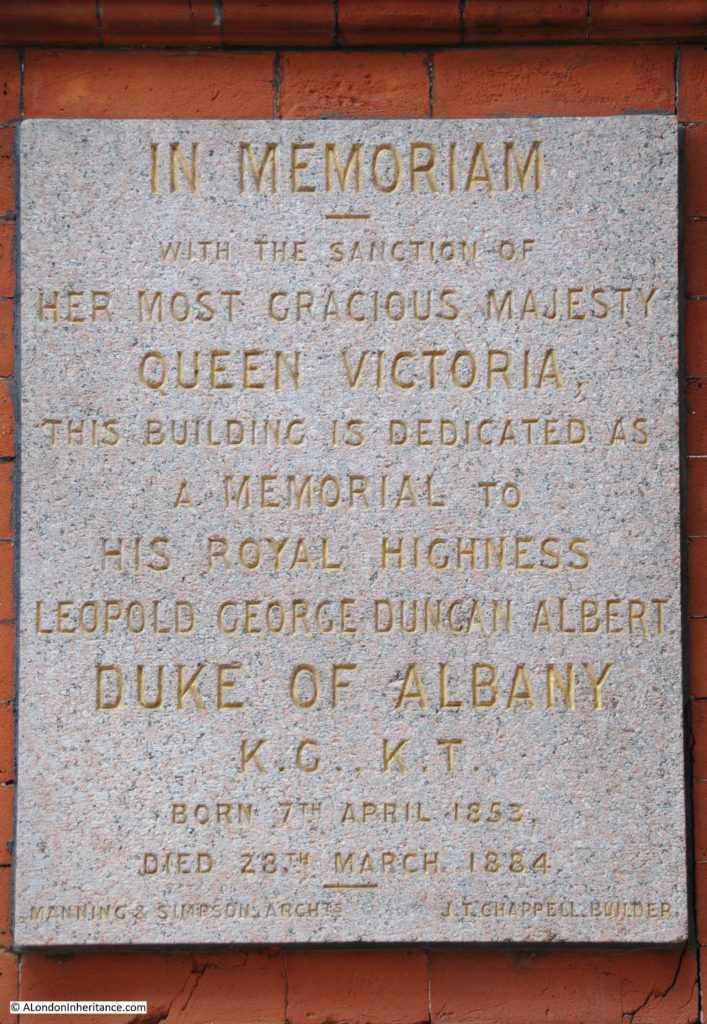

The plaque below is on the building shown above.

Next to the above building, there is a later building, also part of the same hospital, that was opened in 1937. The majority of the building was covered in scaffolding and sheeting, however one of the doors to the street was clear and there is an excellent relief above the door.

This is by A.J.J. Ayres who was born in Paddington in 1902 and worked from a studio in Hampstead. There is a second door from the building which also has another relief by Ayres, however this door was covered when I walked past.

This was the second photo I had taken of this door and relief. When taking the first I surprised a doctor coming out the building who was faced by someone taking a photo at as distance of a couple of feet. he had not noticed the relief before – it is strange how you do not notice things when you pass them so many times.

On the west side of Queen Square is this building – St. John’s House.

Build in 1906 for an organisation of the same name which was founded in 1848 as a ‘Training Institution for Nurses for Hospitals, Families and the Poor’. St. John’s House recruited and trained nurses for many of the major London Hospitals, however in the early 20th century recruitment into a religious training organisation was falling as hospitals were starting to recruit and train their own nurses and the St. John’s House organisation closed in 1919. The building was then used as a centre for nurses who had been trained at St Thomas’ Hospital.

St. John’s House is now occupied by the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging.

There are some rather nice decorative features on the building. At the top of the first floor on the right is the following plaque which records that St. John’s House was founded in 1848 and rebuilt in 1906.

Just below the above plaque is this small stone which records the date of 1906, however the name of the builders appears to be now unreadable.

The plaque on the left of the building:

The building below is the Queens Square Imaging Centre. Owned by the University College London Hospitals Charity it is strange to think that behind this rather ornate facade are some of the latest medical imaging systems.

Reliefs from the top of the second floor of the above building:

The final buildings in my tour of Queen Square are these in this view of the northern side of the square. It is here that during the first decades of the 18th century when the square was built that the square was open to provide views across open countryside up to the hills of Hampstead.

The building on the left was the head offices of the Royal Institute of Public Health and now houses private consulting rooms.

The building on the right is the 1930s apartment block Queen Court. There is a blue plaque on the building for Forest Frederick Edward Yeo-Thomas who lived in Queen Court for a short period. Yeo-Thomas was a Special Operations Executive agent who went on a number of missions to occupied France during 1942 and 1944, ending with his betrayal and capture in Paris. He suffered severe torture by the Gestapo and was sent to Buchenwald Concentration Camp. Following further transfers and a number of escape attempts he managed to escape and made it back to Allied lines in April 1945. After the war he participated in the Nuremberg War Crime Trials, then settled in Paris where he died in 1964.

A couple of years ago in 2015 a potential developer paid £150,000 for the ground beneath Queen Court, presumably with the expectation of building large basement apartments. It seems crazy that the ground beneath existing buildings can now be sold for such ridiculous figures, presumably with no regard for the occupiers of the building above ground.

Limited work has started, however the residents obtained an injunction forcing the developers to halt the work. It will be interesting to see where this goes.

That was a brief run around Queen Square. It is one of the locations in London I like to walk through when I am feeling cynical about London and the over priced apartment buildings that are being built at every opportunity, bland architecture, the loss of local character and disconnection with the past

Queen Square does what London does best. Loads of history, a wide mix of different architectural styles dating back to the first building in the area as London expanded, a concentration of expertise, institutions and professions, all still very relevant today – and a good pub.

Long may it continue.