Leicester Square, along with Piccadilly Circus, are probably the best known locations in London’s west end. A hub of entertainment, hotels and the shops of global brands. Both major destinations for tourists, they are busy places during the day, and late into the night, however Leicester Square started off as a very different place. Part of London’s westward expansion, large houses, terrace houses and ornamental squares.

In the 16th century, this part of west London was all fields. Development of the square, and the source of its name, would come between 1632 and 1636 with the construction of Leicester House, on the northern side of where the square is located today, but at the time the house was built, it was surrounded by fields.

The house was built by Robert Sidney, Earl of Leicester, so as with so many parts of London’s expansion over the last centuries, the square has taken its name from the original aristocratic owner of part of the land, and initial developer.

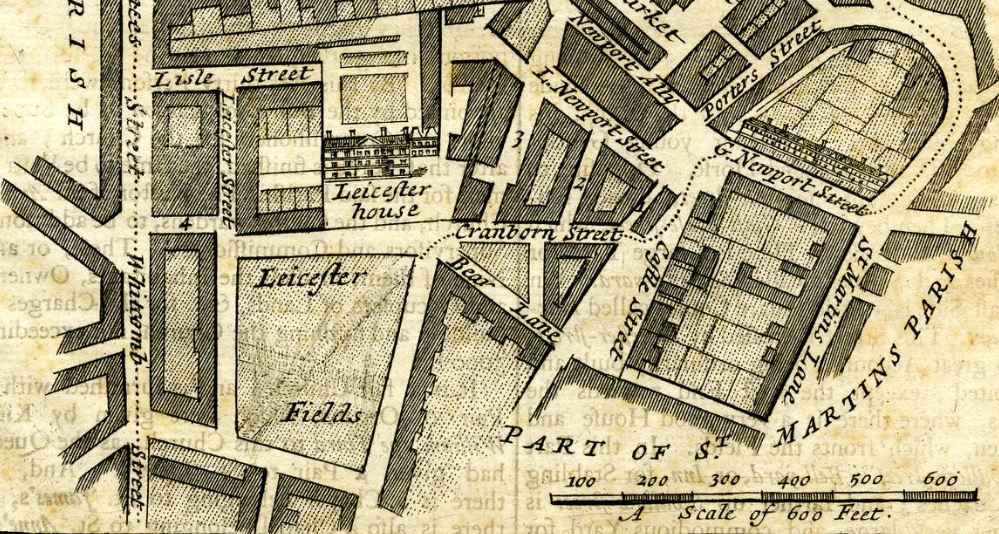

Formation of the square, and building of houses along the sides of the square came in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, and by 1755 the square was developed as shown in the following map, where the square was then known as Leicester Fields, a name from when Leicester House was the only building in the area.

In the above map, Leicester House can be seen on the northern side of the square, with a large courtyard to the front of the house, and gardens to the rear. The fields surrounding Leicester House have been buried under the building of the early 18th century.

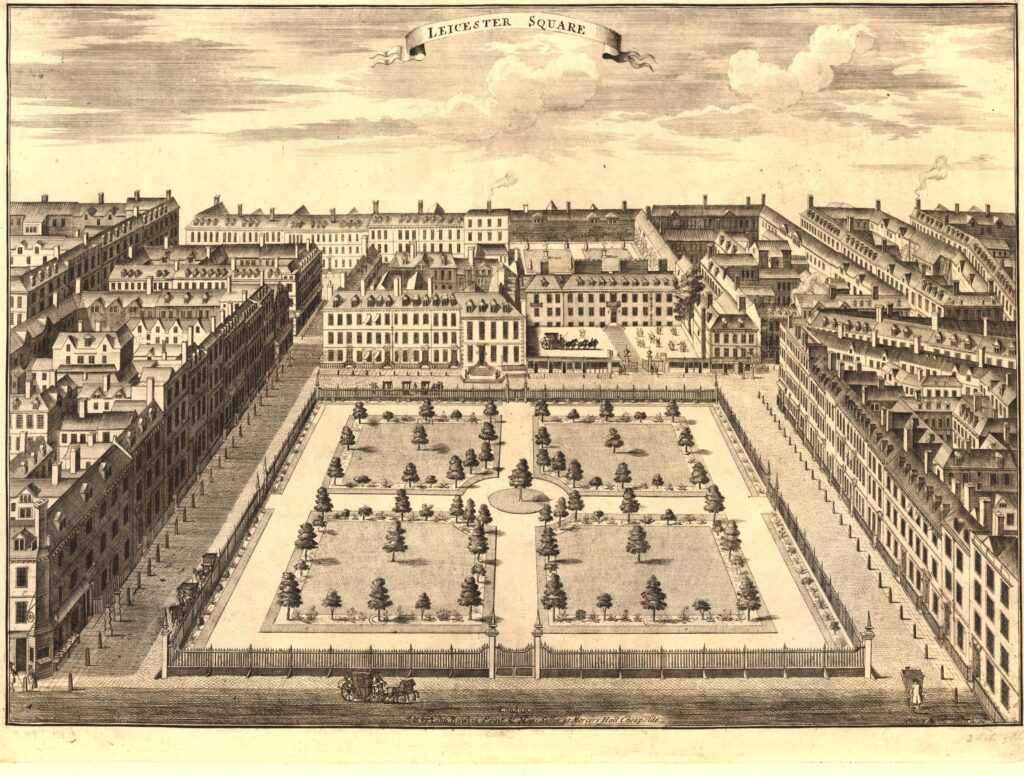

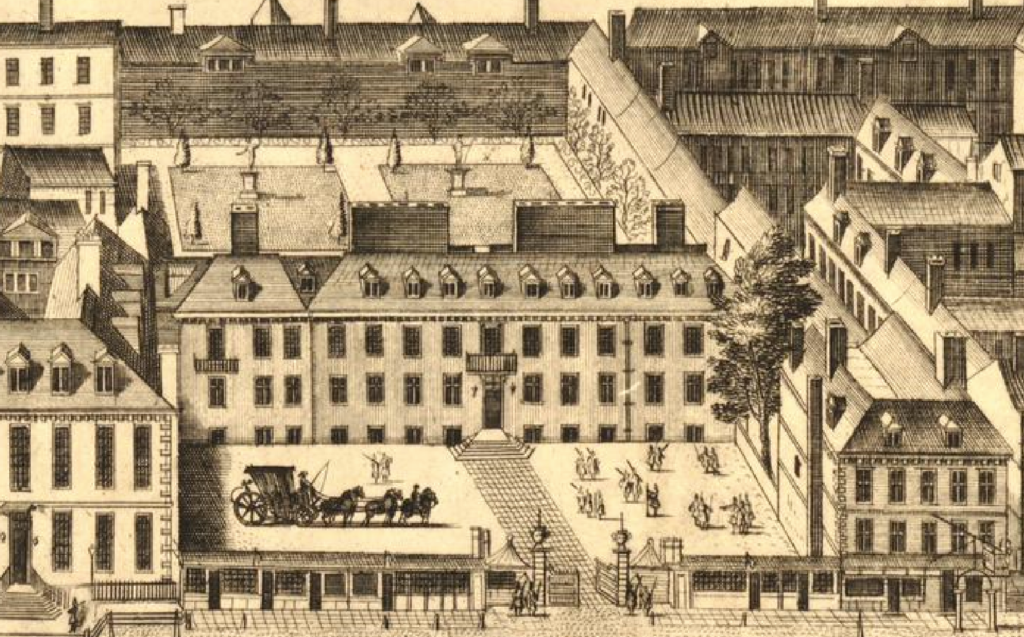

The following print from around 1720 shows the appearance of Leicester Square (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Leicester House can be seen set back from the street on the northern side of the square, and the sides of the square have been developed with the standard terrace housing of early 18th century London.

The central square has been laid out with formal gardens of grass and trees, with paths, and a tree in the centre of the square. This would be replaced with a statue of George I in 1747.

A close-up look at Leicester House shows a horse and coach at the front of the house, along with small groups of people who appear to be holding poles of some type, or perhaps rifles. Large gates protect the house from the street, and there are gardens, stables and outbuildings to the rear:

Leicester House went through a number of different residents, and perhaps the most important was the Prince of Wales who would later become George ll. He had been thrown out of the royal apartments at St. James’s Palace following an argument with his father, King George I, and moved in at the end of 1717.

George I died on the 11th of June, 1727. The Prince of Wales was away from London, but returned quickly to his home at Leicester House, and he was proclaimed King at the gates to his house – the only time that a new King or Queen has been proclaimed in what is now Leicester Square.

The King stayed in Leicester House until the end of 1727, whilst St. James Palace was being prepared for him.

Leicester Square’s first experience as a place of exhibitions and entertainment seems to have been in 1774, when the naturalist Ashton Lever took over Leicester House and turned it into a museum, to house and display his large collection of natural history objects.

The collection remained at Leicester House until Lever’s death in 1788, when it was then moved to the Rotunda in Blackfriars Road.

Thomas Waring, who had worked for Ashton Lever remained at the house until 1791, and it is Waring that offers a clue as to what the people were doing in the early print of the house, where there are people holding what appear to be poles in the courtyard.

Waring was a founder member of the Toxophilite (Archery) Society, and meetings were held at Leicester House, so perhaps those standing in the courtyard were archers with their bows.

Leicester House was demolished around 1791 and 1792.

Following the demolition of Leicester House, the square would rapidly become a destination for entertainments. One major building specifically for this purpose was Wyld’s Great Globe, open between 1851 and 1862.

Constructed in the square by the mapmaker and former Member of Parliament. James Wyld, the purpose of the Great Globe was to show visitors the wonders that could be found across the world, with models, maps and lectures.

A view of the Great Globe, before galleries were constructed at ground level, linking the main entrances, is shown in the following print (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Wyld’s Great Globe was very popular and had very many paying customers. An impression of the educational approach of the Great Globe can be had from the following article in the London Sun on the 6th of June, 1854:

“WYLD’S GREAT GLOBE – Throughout the whole of yesterday, Mr. Wyld’s intelligent lecturer was unceasingly engaged in enlightening such of the public as sought here rather instruction than amusement, upon geographical features of the ‘Great Globe’, devoting, of course, as everybody now does, his chief attention to those parts which are rendered peculiarly interesting by the war with Russia. A brief summary of the Ottoman empire was very appropriately introduced, and served to place in a very clear light the momentous question which is now at issue,

The late discoveries in the Artic Regions likewise came in for a good share of notice; and the dry study of the globe itself, and of the various maps on the subject, was relieved by an inspection of a small, but valuable, collection of dresses, boats, and implements of war, of inhabitants of those unhospitable climes, and of birds and beasts which are found there. These articles are contained in a small anteroom which by clever illusion, is made to resemble a tent with the faint light which is only seen at the North Pole. The juvenile part of the visitors seemed to take an especial delight in examining the different objects in this little chamber.”

Although initially very successful, Wyld’s Great Globe suffered from local competition, and had to look at other forms of entertainment, and started to put on variety shows alongside the educational exhibitions and lectures.

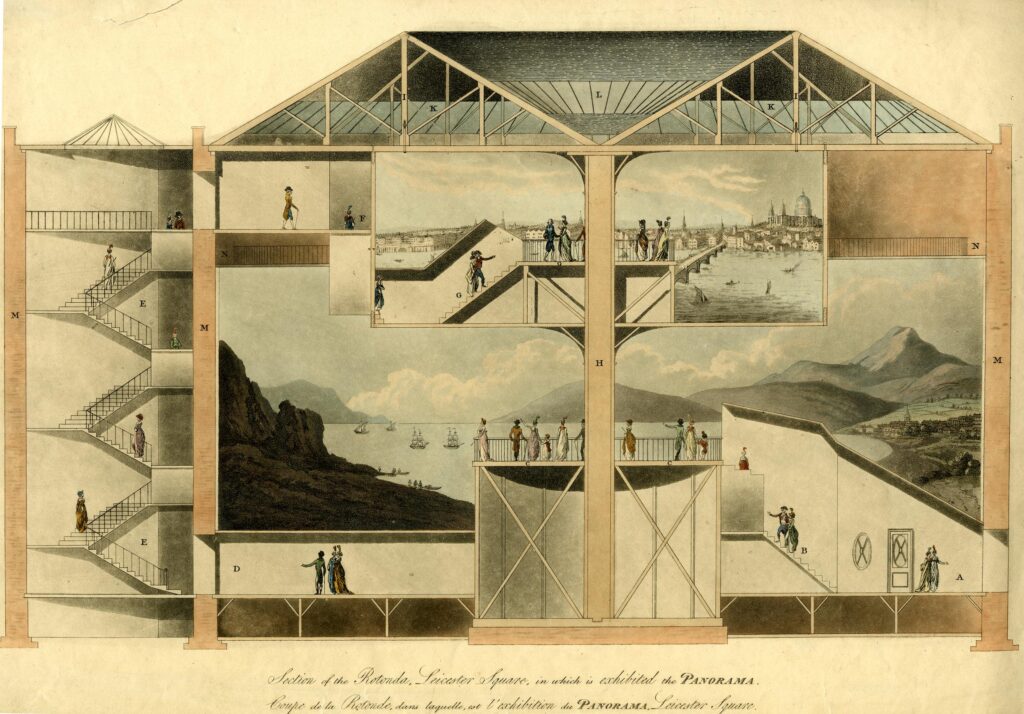

One of the local competitors of Wyld’s was Burford’s Panorama which was located just north of the square, between Leicester Square and Lisle Street.

An idea of the panoramas available can be had from the following advert in the Illustrated London News on the 7th of June, 1851:

“BURFORD’S HOLY CITY of JERUSALEM and FALLS of NIAGARA – Now open at BURFORD’S PANORAMA ROYAL. Leicester Square. the above astounding and interesting views, admission 1s to both views, in order to meet the present unprecedented season. The views of the LAKES of KILLARNEY and of LUCERNE are also now open. Admission, 1s to each circle, or 2s 6d to the three circles. Schools half price. Open from 10 till dusk.”

The following section view shows the interior of Burford’s Panorama, with the views being exhibited on the walls of the circular building (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

Remarkably, the outline of Burford’s Panorama can still be seen today. On the 25th of March 1865, Father Charles Faure puchased the building that housed Burford’s Panorama. and the French architect, Louis Auguste Boileau transformed the building into a new church within an iron structure.

The new church opened in 1868 as Notre Dame de France, a French speaking church in London. The church has an entrance on Leicester Place, but it is only from above that we can see the circular form of the church, on the site of Burford’s Panorama.

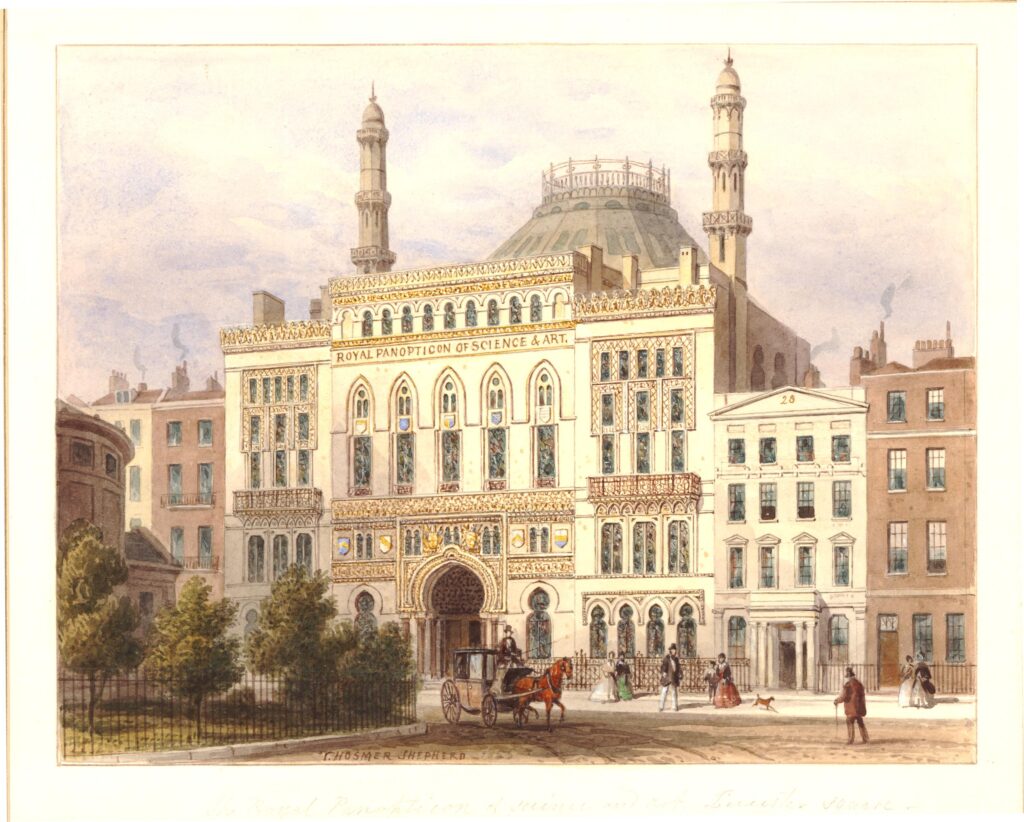

Another competitor to the Wylde’s Great Globe and Burford’s Panorama was the Royal Panopticon of Science and Art, also built in Leicester Square (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The Royal Panopticon of Science and Art opened on the 17th of March 1854, and held scientific and artistic displays and lectures. The Royal Panopticon was popular, often attracting up to 1,000 vistors a day, but did have problems from the day of opening. In their report after the opening, the owners wrote that:

“Since the opening of the institution, everything that had taken place out of doors militated against its success. First of all there was the war; next, the attractive novelty of Crystal Palace, and finally the cholera – all tending to keep the public from visiting the Panopticon, which, under all such disadvantages had nevertheless been successful to a degree greater than could have been anticipated by the council.”

I suspect the owners were being a bit optimistic in their report, as the Royal Panopticon only lasted two years, closing in 1856, when the building became the Alhambra Theatre of Variety, which can be seen in the following photo from 1896 as the large building with domes on the roof. This version of the Alhambra was of a slightly more simple design, having been a rebuild of the original building which was destroyed by fire in 1882.The brick building to the right is Archbishop Tenison’s Grammar School, highlighting the different types of institution that have made Leicester Square their home.

The Alhambra Theatre of Variety seems to have offered a wide variety of entertainments. The following rather cryptic advert from the Westminster Gazette provides details of what was on offer during the evening of the 3rd of October, 1893:

“Alhambra Theatre of Varieties – Open 7:30 – At 8:40 the Grand Ballet, FIDELIA. And at 10.30 CHICAGO, Grais’s Marvelous Baboon and Donkey (first appearance in England), Thora, the Poluskis, R.H. Douglas, The Three Castles, the Agoust Family, and the TILLEY SISTERS &c.”

The Poluskis were the Poluski Brothers, Will and Sam who were born in Limehouse and Shadwell. There is a recording of their act in 1911 online here.

The Agoust family were a family of jugglers and there is a video of their act here.

The type of variety acts that the Alhambra specialised in started to decline in popularity after the First World War. During the 1920s, the cinema began to capture the imagination of those looking for a night out in London, and in 1936 the Alhambra was demolished, to be replaced with the Odeon Cinema, which can still be found on Leicester Square.

Another current cinema which followed a similar path is the Empire Cinema on the northern side of Leicester Square. Originally built as a variety theatre in 1884, the theatre started showing film in 1896, and over the following years started to offer a mix of live performance along with short films.

As with the Alhambra, variety theatre dropped in popularity during the 1920s, and in 1927 the majority of the Empire Theatre was demolished, and rebuilt as the Empire Cinema. The cinema has had a number of major upgrades over the years and it is still open as a cinema today.

The following photo from the 1920s shows the Empire on the left, on a damp night in Leicester Square.

A view across the central square to the northern side of Leicester Square in the early years of the 20th century:

That was a very quick run through of the history of Leicester Square. From the site of an aristicratic house surrounded by fields, to a typical London 18th century square surrounded by fine houses, which then became the site of 19th century entertainments, which have continued into the 20th and 21st centuries, with only really technology changes that have resulted in film replacing panoramas and variety theatre as the popular source of entertainment.

Time for a walk around the square. The view from the north-east corner:

On the north-east corner of Leicester Square is Burger King, housed in a rather impressive building.

The building was originally the Samuel Whitbread pub, opened in December 1958, and was Whitbread’s attempt at reviving London’s post war pub trade. Designed by architects TP Bennett & Son, with four distinct interior spaces by designers Richard Lonsdale-Hands Associates.

The pub was very much a 1950s design, and during the 1960s it started to seem dated, and did not have the benefit of being a traditional London pub to help.

Whitbread sold it to Forte in 1970, who renamed it as the Inncenta, however by the late 1970s, the pub, along with much of Leicester Square was becoming rather squalid, and suffered from lack of investment.

The building may change again, as the owners, Soho Estates are looking to redevelop the building to make it more of a “destination” site in Leicester Square.

View of the north-east corner of Leicester Square:

The Empire Cinema on the north side of the square, showing how buildings on the square have continued to adapt, as the site now has an IMAX cinema as well as a casino.

The above photo was taken within the central square, and the following photo is looking towards the central statue.

The gardens of Leicester Square are today rather basic. Surrounding trees with grass on the outer sides of the square. The square has been used for a number of commercial activities that take over the square. for example, in pre-Covid days, there was a Christmas Market across the square in the weeks before Christmas.

The square though does have a secret, as below the square is a key part of the West Ends electricity distribution infrastructure.

Below the square is a large, multiple level, electricity substation. The substation basically takes high voltage feeds from the main distribution network, and “transforms” this high voltage down to the 240 volts that ends up in the sockets of local homes, businesses and shops.

Large devices called transformers perform this function, and earlier this year the third of three new transformers arrived at Leicester Square as part of an upgrade of the substation in order to support the increasing demand for electricity in the West End. The southern part of the square is still fenced off as part of this upgrade.

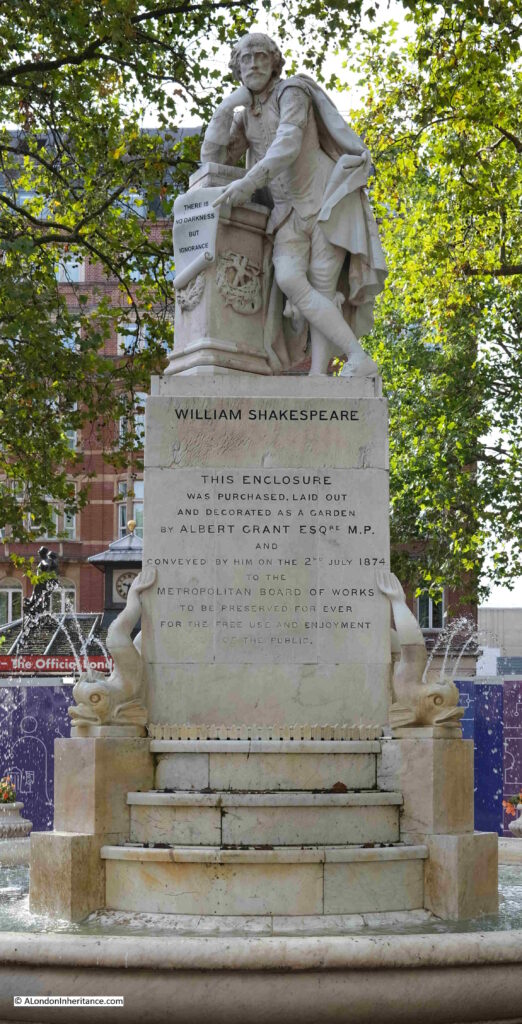

In the centre of square today, is a statue of William Shakespeare, with below an inscription that records that the square was purchased, laid out and decorated as a garden by Albert Grant, and conveyed by him to the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1874:

The Graphic on the 4th of July 1874 provides some more details on how and why this happened, after the demolition of Wyld’s Great Globe:

“Bit by bit the rusty iron railings were filched away, while the statue of King George II on horseback became a butt of practical jokers. On one occasion (and at considerable expense) some systematic wags bedaubed it with whitewash, and finally the horse and rider parted company, the latter lying prone in the mud. The old proverb that when matters come to their worst they must perforce mend. Leicester Square had attained its nadir when Sir George Jessel decreed that the freeholders were bound to restore the Square to its original state of respectability.

The freeholders were preparing to appeal this decision, the Board of Works were about to apply to Parliament for powers to purchase the site, when Mr. Albert Grant, MP for Kidderminster, appeared on the scene, and has since acquired the freeholder property. Mr. Grant resolved to make a most generous and patriotic use of his purchase, by laying out this hitherto desolate area as an open ornamental place, provided with walks, lawns and parterres of flowers. The whole of the works have been designed and completed under the superintendence of Mr. Knowles, the well-known architect; and on Thursday last Mr. Grant handed over this munificent present to the Metropolitan Board of Works, as trustees for the people of London.”

The statue of William Shakespeare dates from the 1874 restoration of the square by Albert Grant. It was sculpted in marble by Giovanni Fontana, and is modeled on Peter Scheemaker’s monument in Poets Corner at Westminster Abbey.

Shakespeare is pointing to the phrase, “there is no darkness but ignorance” which comes from the play “Twelfth Night”

View from the square towards the Odeon Cinema:

Leicester Square today is a major tourist destination, and therefore attracts major international brands. One such being Lego, who have a queuing system outside their store. This helps manage the numbers inside, but also enhances the image if you can show large queues wanting to get inside your store.

The view towards Piccadilly, with the Swiss glockenspiel, which was originally on the Swiss Centre, which was demolished in 2008. I have some photos of that which I still need to find and scan.

A hotel, and large store for M&Ms was built on the site of the Swiss Centre:

A recent addition to Leicester Square is a Greggs. Not a global brand, and I do find the thought of a Greggs in Leicester Square, alongside the flagship stores of Lego and M&Ms, rather amusing.

Around the square are various works of art that represent characters from films, including Gene Kelly in a scene from Singing in the Rain:

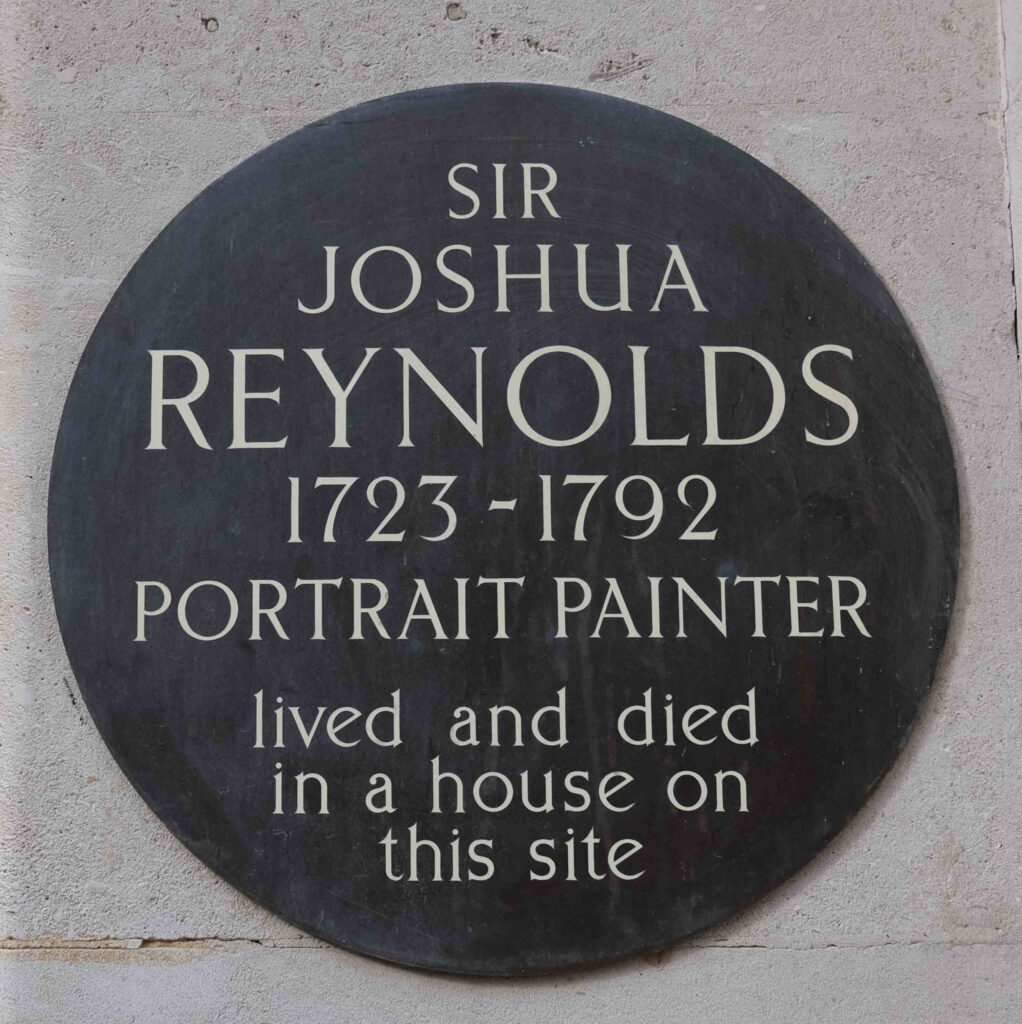

The west side of the square with an All-Bar-One and a McDonalds. Just visible is a plaque between the two buildings.

Which records that the portrait painter Sir Joshua Reynolds lived and died in a house on the site, as well as where numerous members of the aristocracy and society sat for Reynolds to have their portrait painted.

Reynolds was not the only artist who lived in Leicester Square. William Hogarth had his main home in the south-eastern corner of the square. This was his central London base, and his house in Chiswick was his country retreat.

The southern side of Leicester Square:

For many years there has been a theatre ticket centre on the southern side of the square, selling tickets for shows that evening, or the coming days.

The hoardings on the right in the above photo are screening off the work site where upgrades are being made to the electricity substation below the square.

The eastern side of the square:

The building on the right is the offices of Global Radio, the company that owns radio stations such as Capital Radio and LBC – the two original London commercial stations that have since morphed into national brands.

The TGI Fridays on the ground floor was once the Capital Radio Cafe, which, and speaking from experience, was a perfect venue for early teenage children’s birthday parties.

Between TGI Fridays and the Odeon cinema, is Leicester Square’s only pub, Wetherspoons The Moon Under Water:

The pub dates from around 1992. Number 28 was one of the original Leicester Square houses that was demolished towards the end of the 19th century, and, following the mid 19th century approach to have exhibitions for entertainment, housed the Museum National of Mechanical Arts.

In the 1930s, number 28 was the site of the “400 Club” which was known as the club for the upper classes and aristocracy, with Princess Margaret becoming a regular client of the club in the 1950s. The Tatler would often have reports of who was to be seen at the 400 Club, and would include photos of men in Dinner Jackets and women in expensive jewelry.

That was a very quick tour of the history of Leicester Square. A square that started off as one of London’s typical residential squares, with fine houses and a central square, although with the unusual feature of Leicester House to the north.

A square that has quickly evolved into one of London’s centres of entertainment, starting with panoramas and scientific displays and lectures, which then became a home for variety theatre and then London’s hub for cinema, and which is where the majority of major films have their UK premier.

In the coming week, The Last Heist premiers at the Vue cinema in Leicester Square on Wednesday the 2nd of November, followed by Black Panther: Wakanda Forever at Cineworld on Thursday the 3rd.

However popular entertainment evolves in the future, I am sure that Leicester Square will play some part in being London’s West End hub.