Many of London’s buildings seem so substantial that they almost appear permanent, however looking back there have been so many buildings of all types that at the time must have seemed destined for a long future, but in reality would only grace the city streets for a limited number of years.

There are so many trends that influence the buildings that spring up across the city. Changing work and living patterns, the economy, financial incentives, industrial changes, government policy, transport etc. and it is interesting to speculate how this might continue as the city we see today is only ever a snapshot of a point in time.

In 30 years time will there be campaigns to preserve the Walkie Talkie building, threatened with demolition as with technology changes there is a significantly reduced need for office space in the City and the City of London is now approving hotel and apartment building? Demand for office space across London may be reduced in the next few years as more companies recognise the economic benefits of staff working from home?

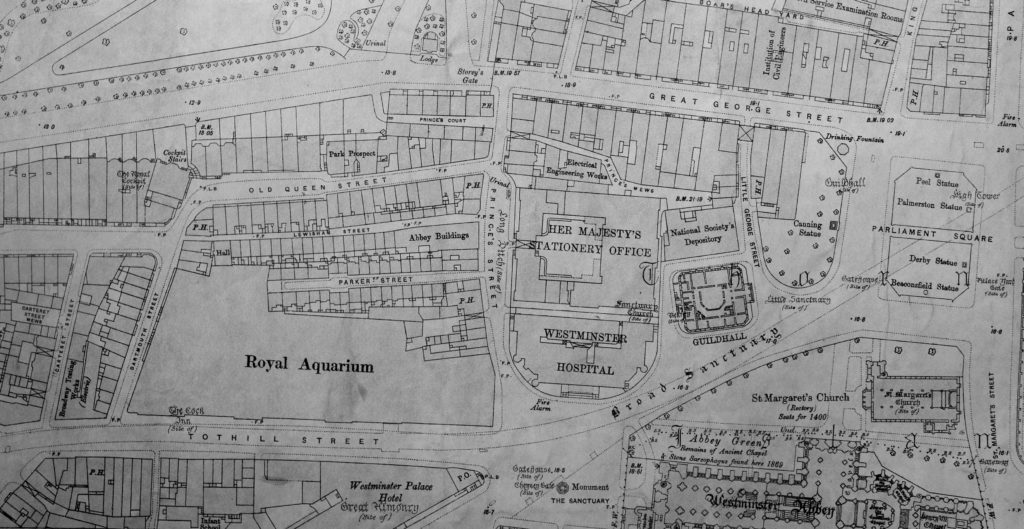

What got me thinking about this was looking at a map, and seeing a large building that was only in existence for a few decades.

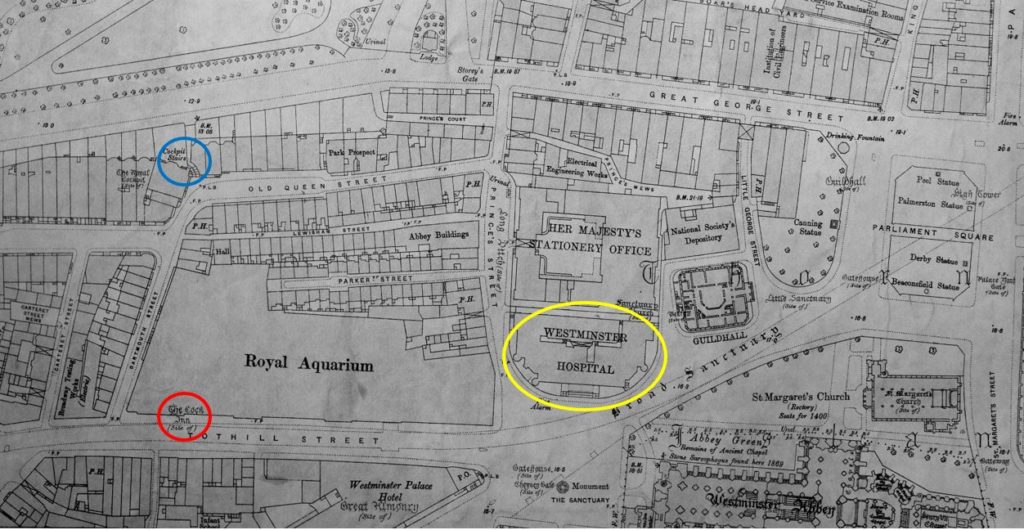

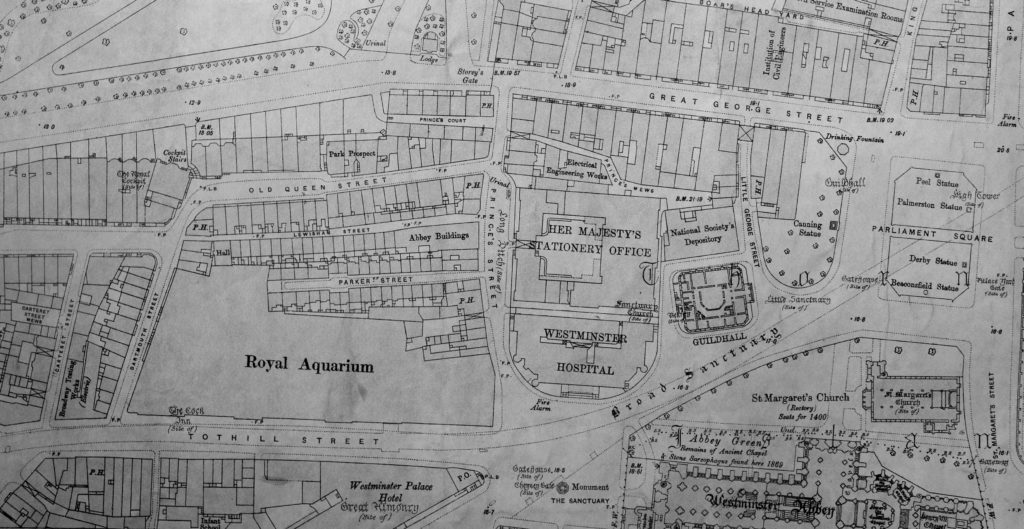

Last summer, a reader generously gave me a number of maps, including large-scale Ordnance Survey maps from the end of the 19th and start of the 20th century. One of these covered Westminster, and just opposite Westminster Abbey, there was a large building with bold lettering naming the building as the Royal Aquarium.

The Royal Aquarium was a rather magnificent building, as illustrated by this view of the building from the book The Queen’s London. the view is from the yard outside Westminster Abbey. Tothill Street is running to the left of the Royal Aquarium.

The Royal Aquarium had a relatively short life. Opened in April 1876, it was demolished in 1903, to make way for the building that we find on part of the site today – the part facing Westminster Abbey – the Methodist Central Hall.

The Royal Aquarium was built by the Royal Aquarium and Summer and Winter Garden Society, a limited company which had been set-up with an initial £200,000 of capital through the sale of shares of £5 each.

An aquarium had recently been built in Brighton and was financially very successful with the shares at a 30% premium to their original sale price, and the Society argued that the same success could be achieved in London, although I would have thought that a sea-side town like Brighton was a much more suitable location for an aquarium than central London.

Despite the name, the Royal Aquarium would cover far more than the display of marine life, and it was intended to deliver, in the Victorian approach of such institutions, cultural and educational entertainments. These would include “vocal and instrumental performance of the most brilliant manner, supported by a splendid orchestra and best known artists of the day”. The Royal Aquarium would also feature Reading Rooms, a Library and Picture Gallery.

The Royal Aquarium and Summer and Winter Garden Society was soon renamed the Royal Westminster Aquarium Company. Opening commenced in January 1876 with a formal opening of the main building by the Duke of Edinburgh. The rest of the building’s facilities opened during the following months with the theatre opening in April.

The Royal Aquarium was a really big building, and some idea of the scale can be had from the following description from The Era on the 3rd of October 1875:

“The Royal Aquarium promises soon to be an accomplished fact, for already the building is so far advanced that on Tuesday, in response to the invitation of the Managing Director, a number of gentlemen inspected the works.

There is still, of course, a great deal of scaffolding to interrupt the view of the building. Still enough can be seen to form some idea of the size, grace and elegance of design of this new addition to the pleasure resorts of the Metropolis.

The large tanks for fish on each side of the great central avenue have sills of polished granite, and are lighted both from above and at the back; the plate glass in front being one inch in thickness. the whole of the flooring of encaustic tiles on concrete cement is now being laid down. The promenade, or winter and summer garden, is about 400 feet long by 160 feet wide, and is approached by two bold entrances from the Tothill-street frontage, surmounted by pediments; with representations of Neptune and the sea-horse, above which rises a figure of Britannia, twelve feet in height.

The height of the gallery from the floor of the promenade is sixteen feet and from this level to the springing of the vaulted roof is about sixteen feet. The whole height from the floor level to the top of the roof is seventy-two feet. The galleries round the building are forty feet in width, a large portion being set apart for refreshments. On the north side in the centre is the large orchestra, sixty feet by forty feet. The concert room at the west end is a noble and lofty apartment, and is capable of being converted into a large and handsome Theatre. It is 106 feet long by sixty-six feet in width. the stage is thirty feet in width to the sides of the proscenium, and forty-three feet in depth.

There are also two galleries, which, together with the ground-floor space, will accommodate an audience of 2,500 persons. About 800 tons of iron have been used in the construction of the building.”

The name Royal Aquarium does not really cover the multiple functions that the building could serve, as from the description, with the galleries, large promenade, concert room / theatre, this really was a multipurpose space, capable of being converted to host a range of different functions.

The Royal Aquarium photographed in 1902 from Victoria Street:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_536_78_7349

There was some criticism soon after opening regarding the lack of marine life, for example: “It was said that the Aquarium does not deserve its title because there were no fish, but great efforts have been made of late to stock the tanks, and some drawback in their construction and arrangement having been removed, the public will have the opportunity of judging the Institution fairly.”

The Royal Aquarium was eventually well stocked with a variety of marine live, however the methods used to transport animals to the Aquarium were very basic and often resulted in a tragic outcome.

In 1877 a whale was being delivered to the Royal Aquarium from Labrador, Canada, however on arrival it was found to be suffering from what appeared to be a bad cold, with mucus coming from the whale’s blow hole. It arrived on a Wednesday but died the following Saturday. The lungs of the dead whale were found to be very badly congested and the cause was identified as the method used to transport the whale.

It had been on an exposed open deck during the trip across the Atlantic, and had been covered in sea water every five minutes, however water evaporated quickly between the regular soaking, which resulted in extreme cold, and the subsequent impact on the whale’s lungs.

A very barbaric treatment of the whale for the sole purpose of entertainment.

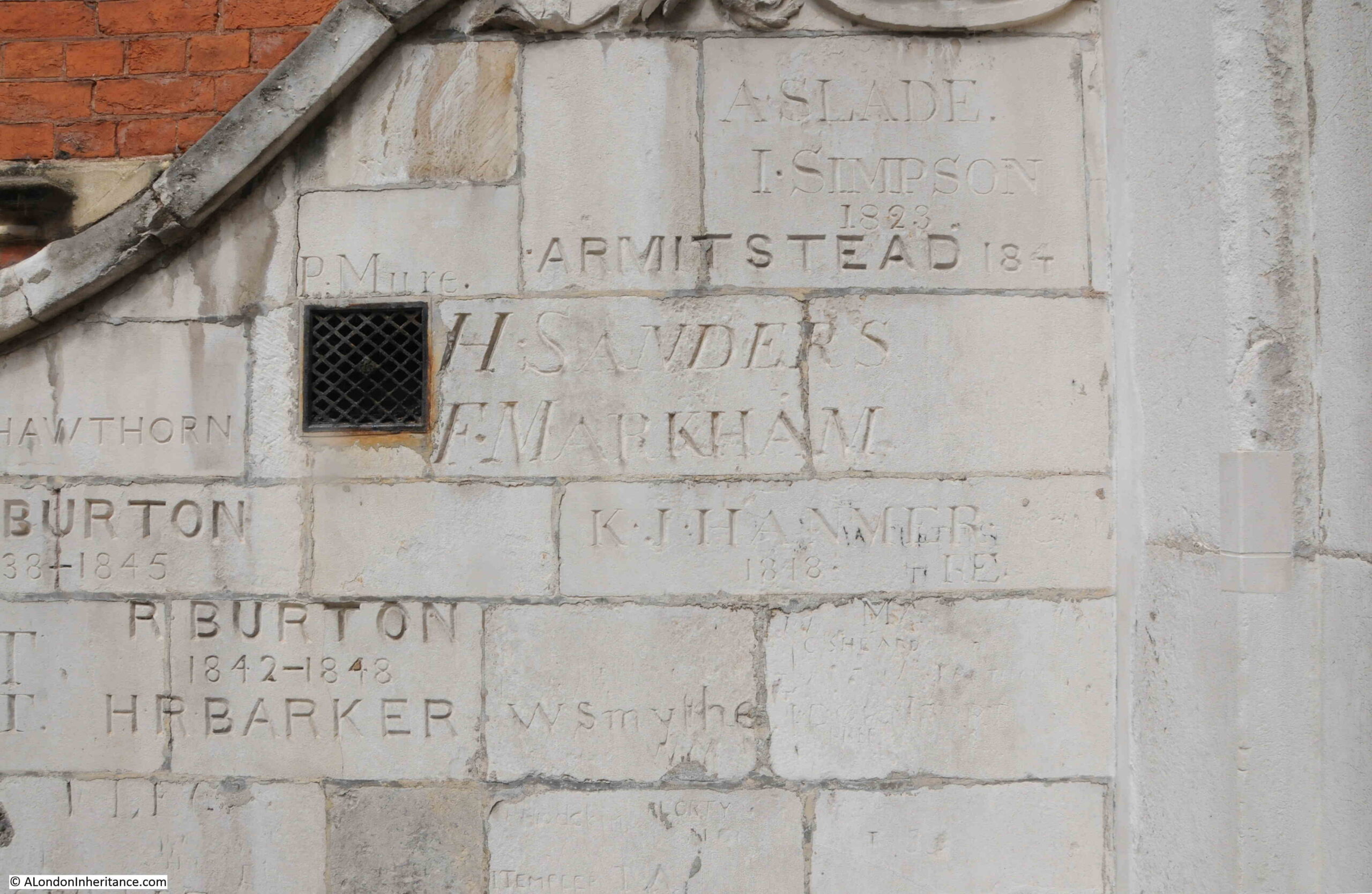

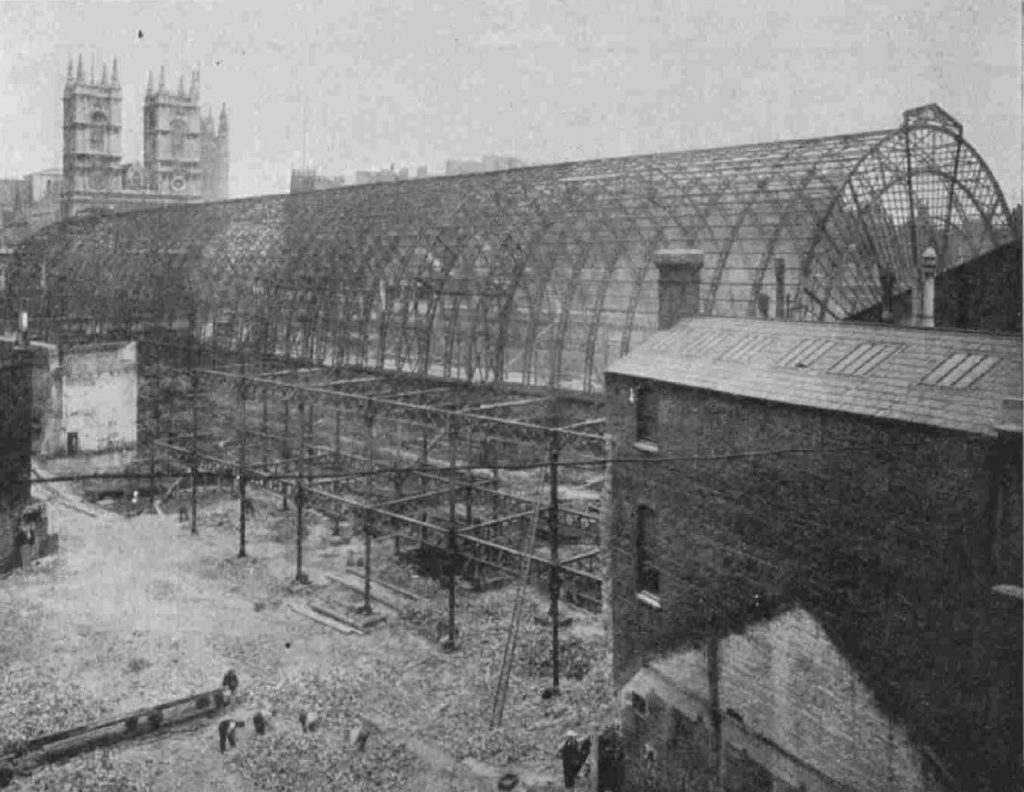

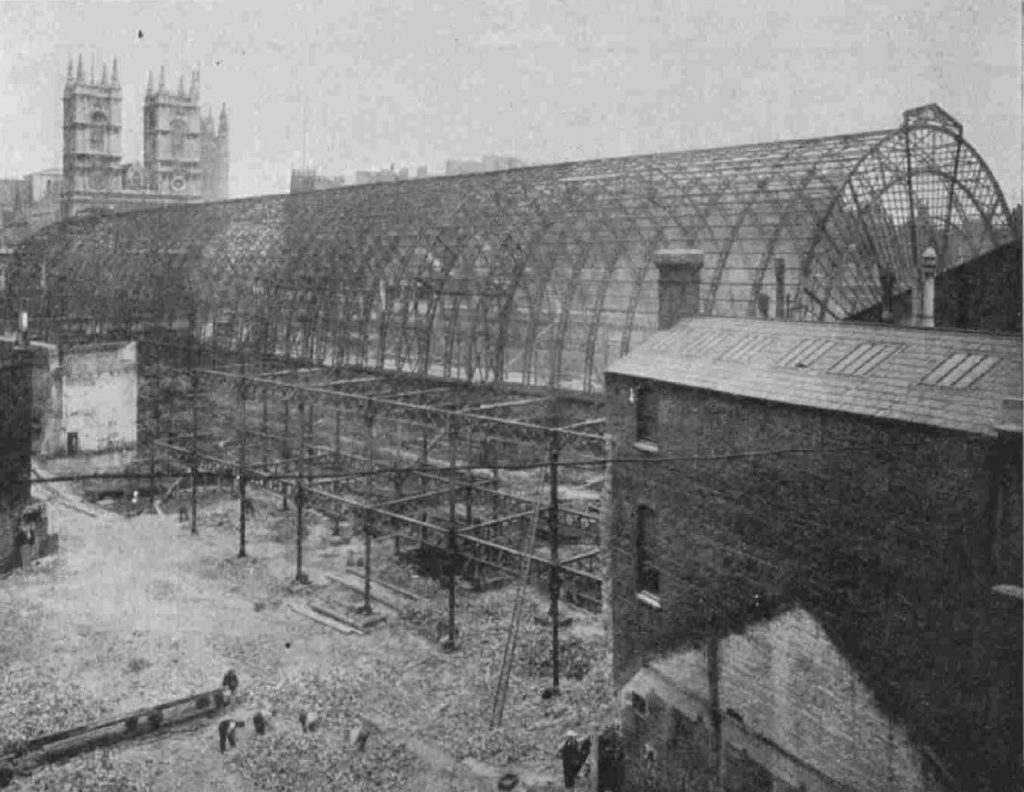

Some idea of the scale, the volume of iron used, and the way an iron framework was used to construct the building can be seen from the following photo that was taken during demolition of the Royal Aquarium (note the twin towers of Westminster Abbey in the background):

The following drawing shows the interior of the Royal Aquarium:

Picture credit: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

From the above view it can be seen that the design was very similar to that of the Great Exhibition, with a long central space covered by a glass arched roof. Side galleries also ran the length of the building.

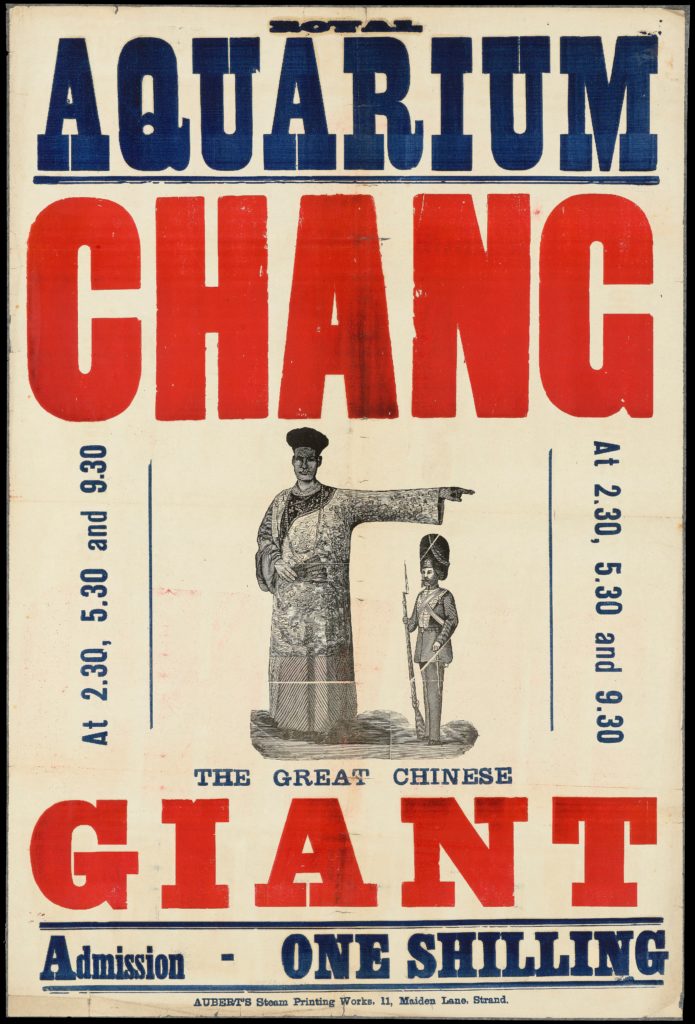

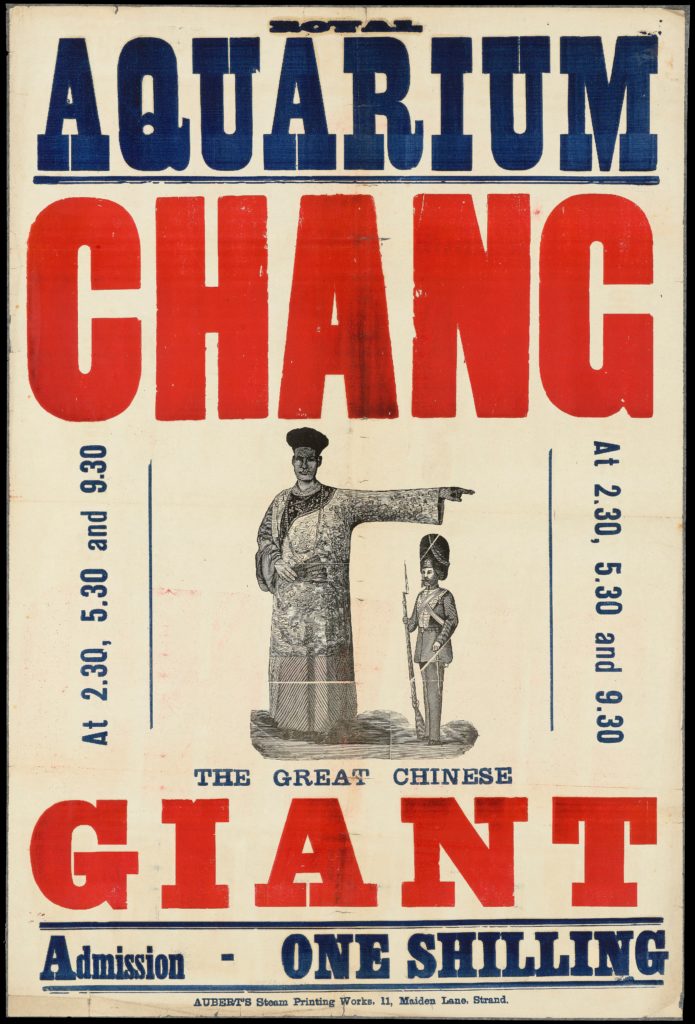

Entertainment at the Royal Aquarium was what would be expected of late Victorian mass entertainment, consisting of Music Hall style acts along with people who were considered very different to the norm. One being Chang the Great Chinese Giant:

Credit: Poster: Royal Aquarium : Chang, the great Chinese giant : admission one shilling. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Chang, according to his obituary, was born in China in 1842. He came to England in 1868 and toured extensively across the UK and Europe, including displays at the Royal Aquarium. It was claimed he was 8 foot tall.

He settled in England and married a woman from Liverpool, but settled on the south coast at Bournemouth, where he was listed as a resident under the name of Mr Chang Woo Gow. He was known for his readiness to help and get involved in local matters, he sold Chinese objects at charitable bazaars and exhibited at local art exhibitions.

He died in 1893 at the age of 51 and was buried in a local Bournemouth cemetery in the same grave as his wife. His coffin was reported as being 8ft 6in long. Chang and his wife had two sons who were still alive at the funeral of their father.

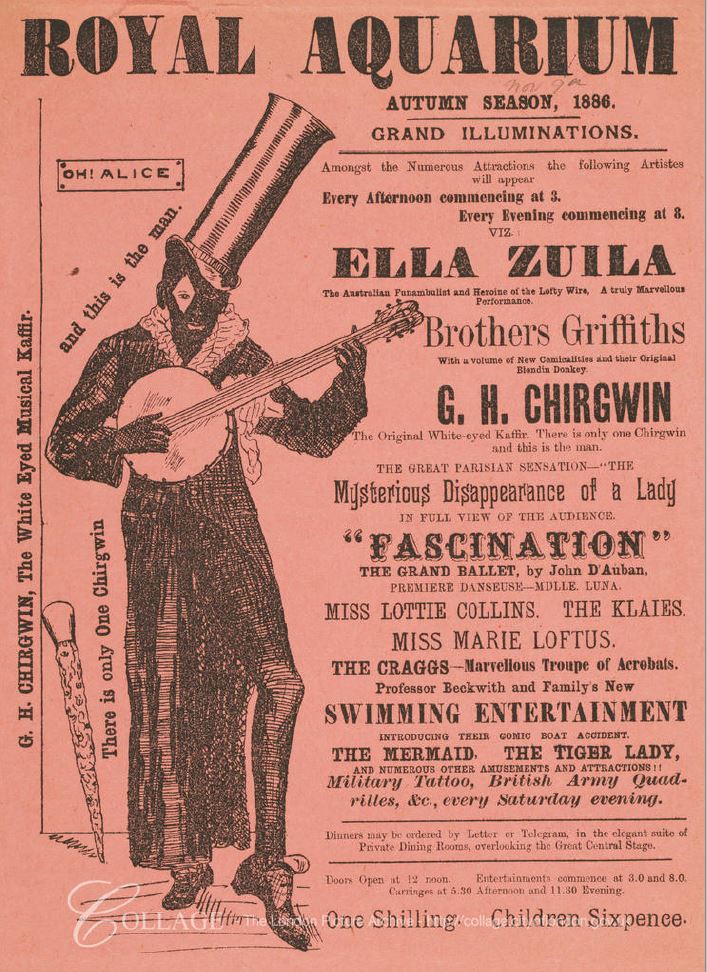

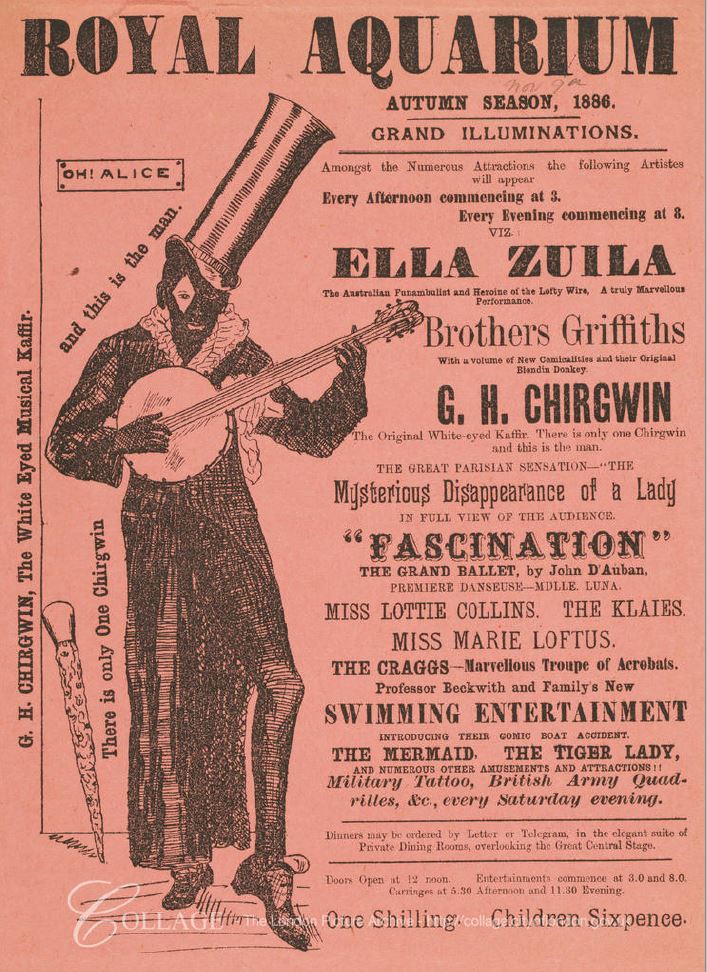

Other entertainments were similar to those put on at a Music Hall, but on a much larger scale. The following is the Autumn Season in 1886, where you could see the Mysterious Disappearance of a Lady, in full view of the audience, or Professor Beckwith and Family’s New Swimming Entertainment.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_GL_ENT_125b

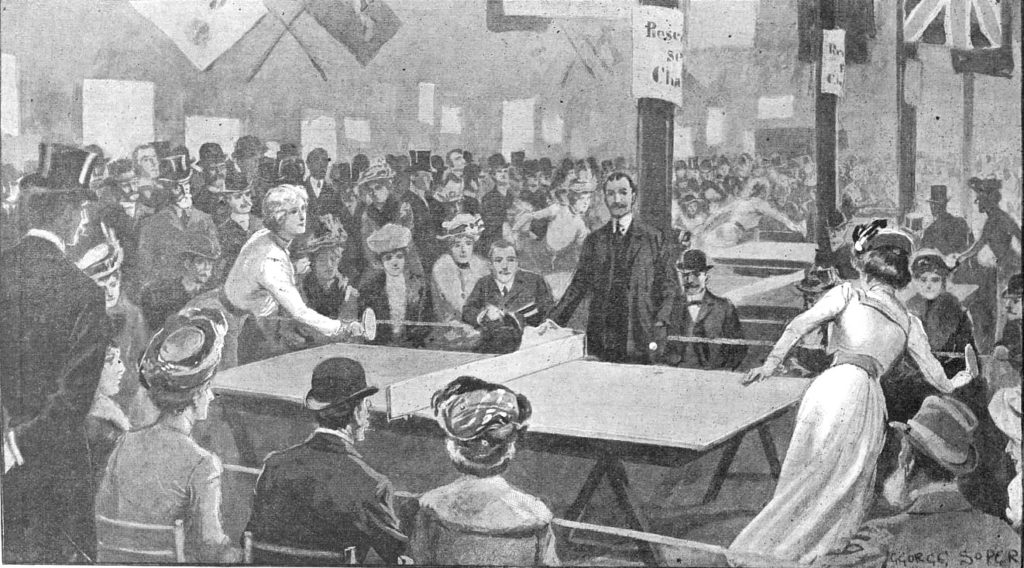

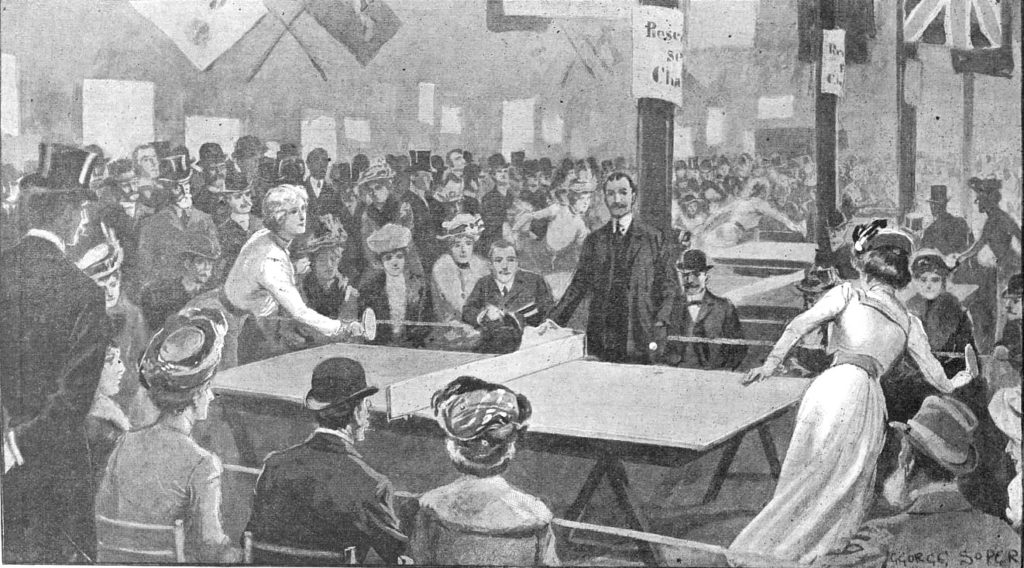

One of the events hosted in the Royal Aquarium was when the management “scored a great success with their first ping-pong or table tennis tournament”.

The drawing below shows the final in the ladies section between Mrs Thomas and Miss V. Eames, when “each lady scored one game and twenty-five points, upon which it was decided to play for five consecutive points, Miss Eames ultimately scoring, and winning the ladies championship.”

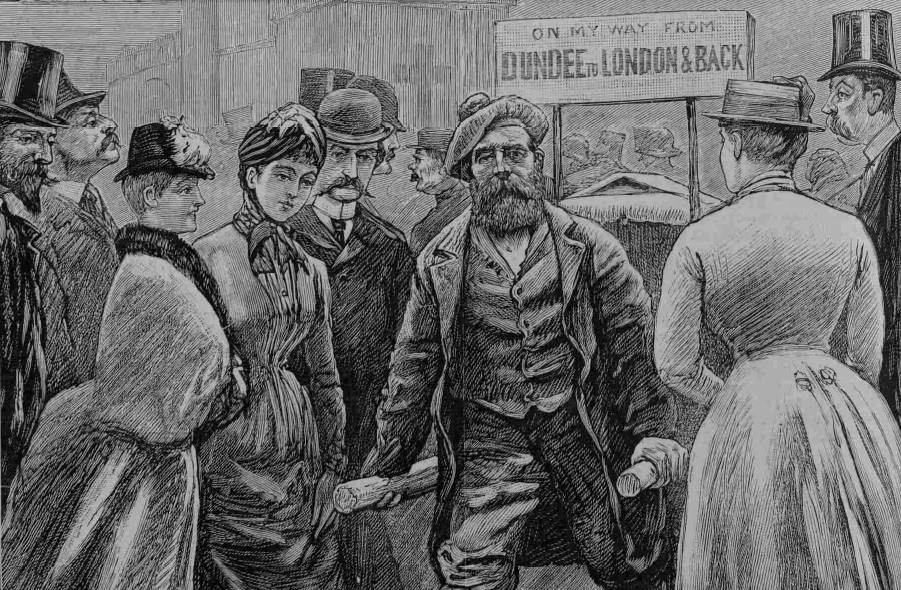

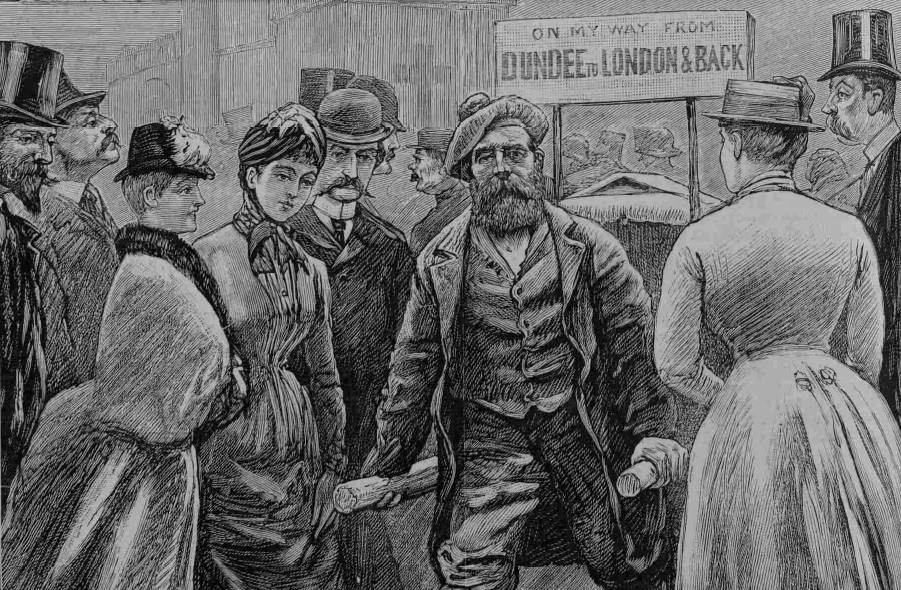

A very different appearance at the Royal Aquarium, was that by James Gordon, a street-porter from Dundee, in December 1886.

He was 47 years old, and originally apprenticed as an engineer, however he had his right hand smashed at work and lost his thumb and three fingers. He then tried work as a baker, as a painter, before finally working as a light porter in Dundee. He had twelve children. four had died and one had emigrated to New Zealand. Finding work was difficult and some weeks he would only earn four shillings.

With his disability, there was very little hope of finding any better work, so he decided to push a wheel barrow from Dundee to London and back – a distance of roughly 1,000 miles.

On reaching London, he rested for three days and appeared at the Royal Aquarium, where many visitors came to see him. He had a collecting box in his wheel barrow and people put in money during his journey, and at each town he stopped at, he would pay in the money at the Post Office, to be sent back to his wife at Dundee.

Mr James Gordon pulling his wheel barrow and setting of at the start of his return journey from London to Dundee.

By the early years of the 20th century, the Royal Aquarium was in decline. It had grown a slightly dubious reputation as the newspapers of the time reported on the “single women” who would walk the galleries of the building.

So after a short 27 years in existence, the main building closed in January 1903. At the closing performance, the president and managing director of the aquarium company referred to some of the successful entertainments put on at the Aquarium, including Ladies’ Cycle Races, a Boxing Kangaroo, and that the public had paid one shilling a seat to watch a man in a trance awake (an experience that was compared to simply watching a sleeping man wake up !!). The theatre would continue on until 1907 when it too would be closed and demolished.

The site would soon be handed over to the Wesleyan Methodists, who would build their new Central Hall which would be open by 1912. The Central Hall today, from along side the Queen Elizabeth II Centre:

Although the Methodist Central Hall has a very different purpose to the Royal Aquarium, the building is now the location for the BBC’s New Years Eve concert before and after the fireworks, so there is a small entertainment link remaining with the popular culture of the Royal Aquarium.

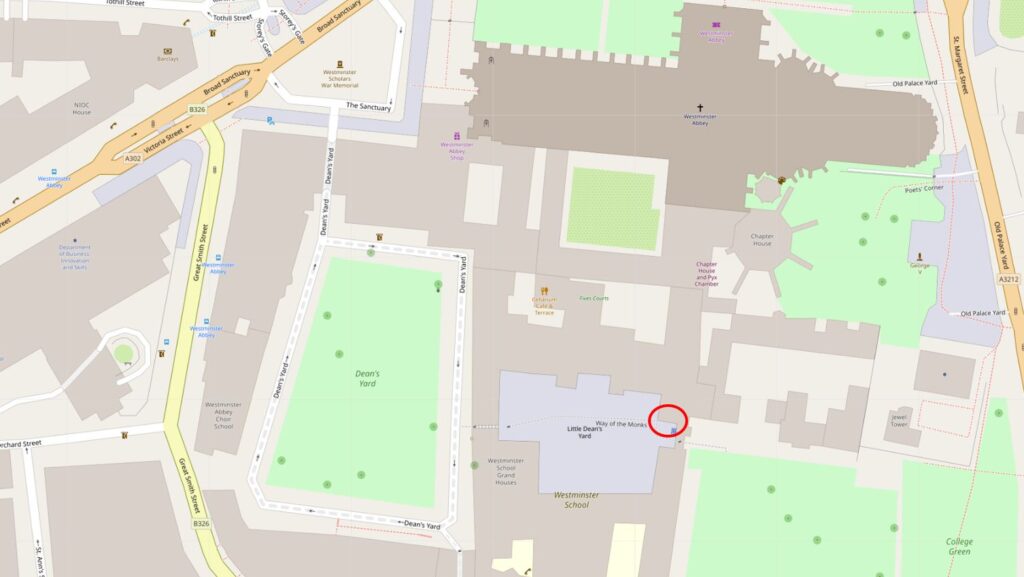

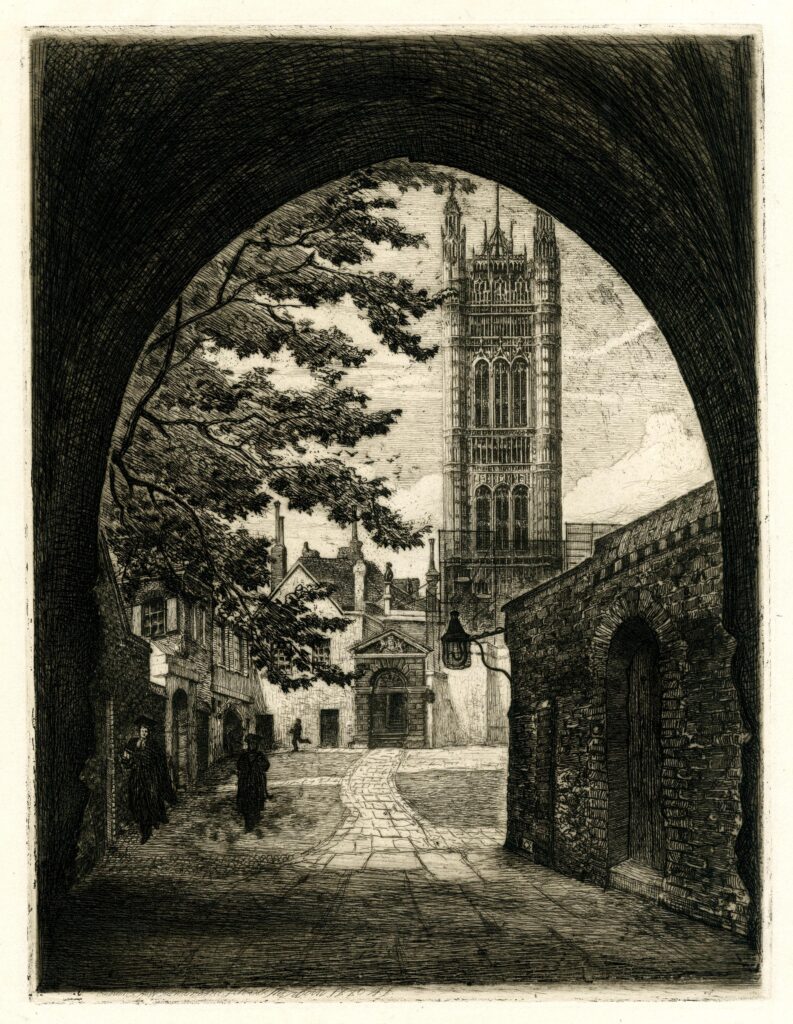

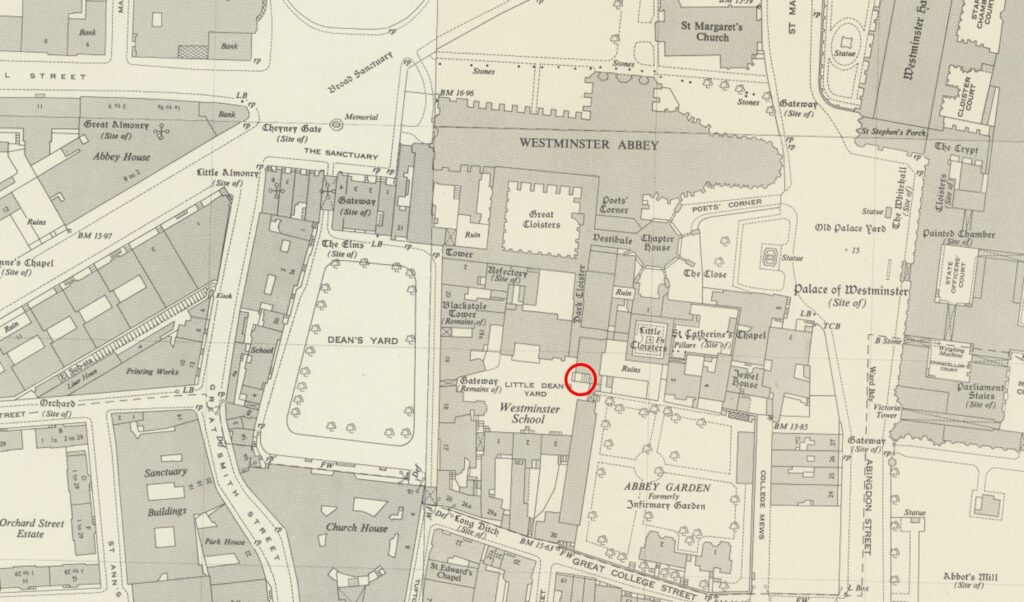

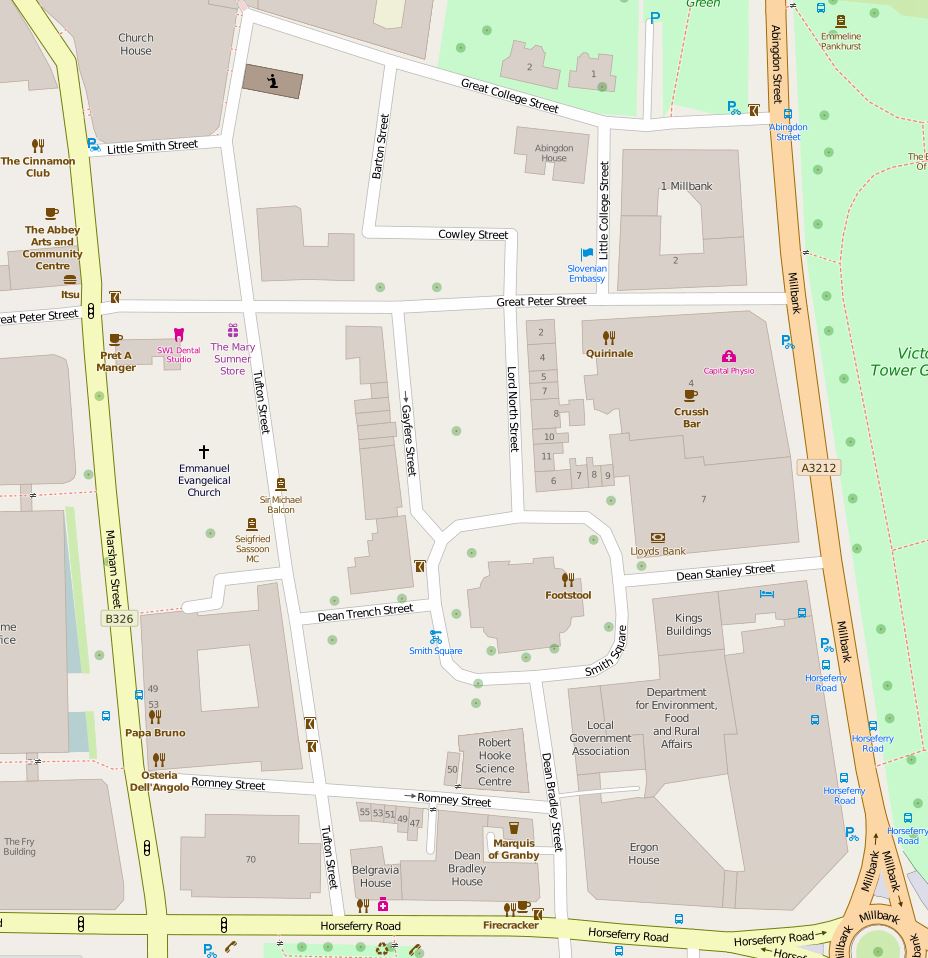

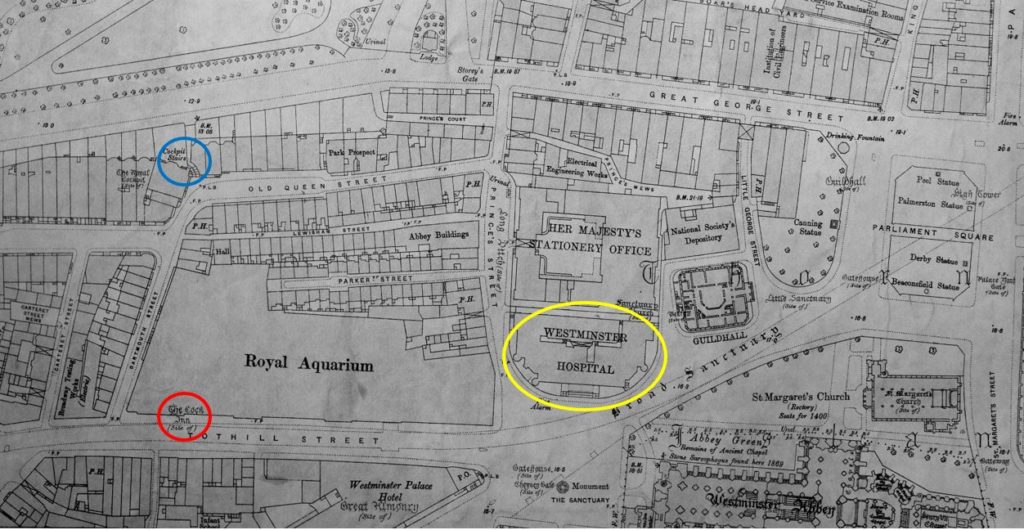

The Ordnance Survey large-scale maps are fascinating, there is so much detail to discover. In addition to the Royal Aquarium, I have circled three other sites:

The red circle is around some text stating The Cock Inn (site off).

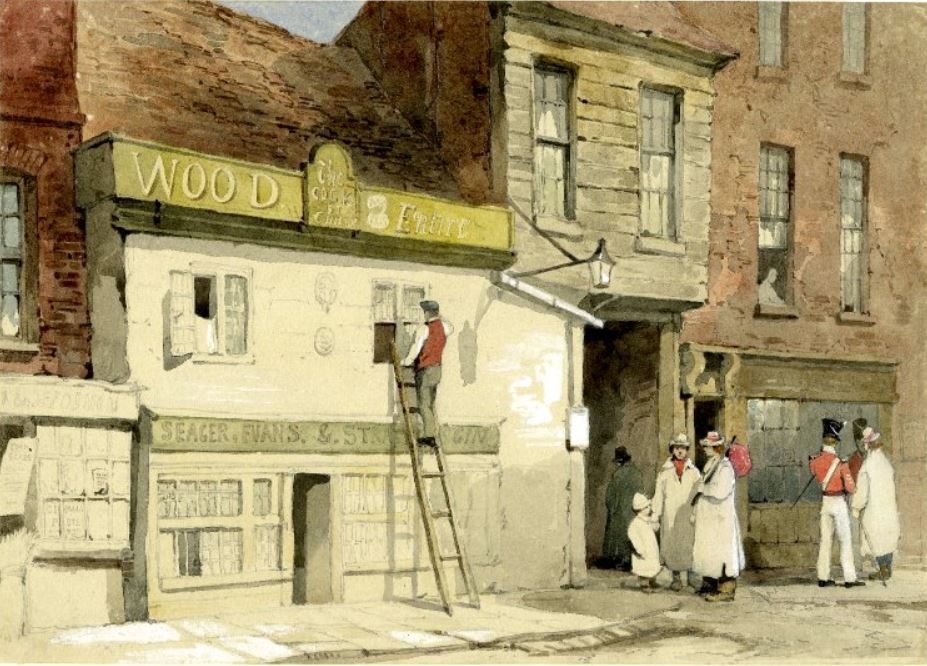

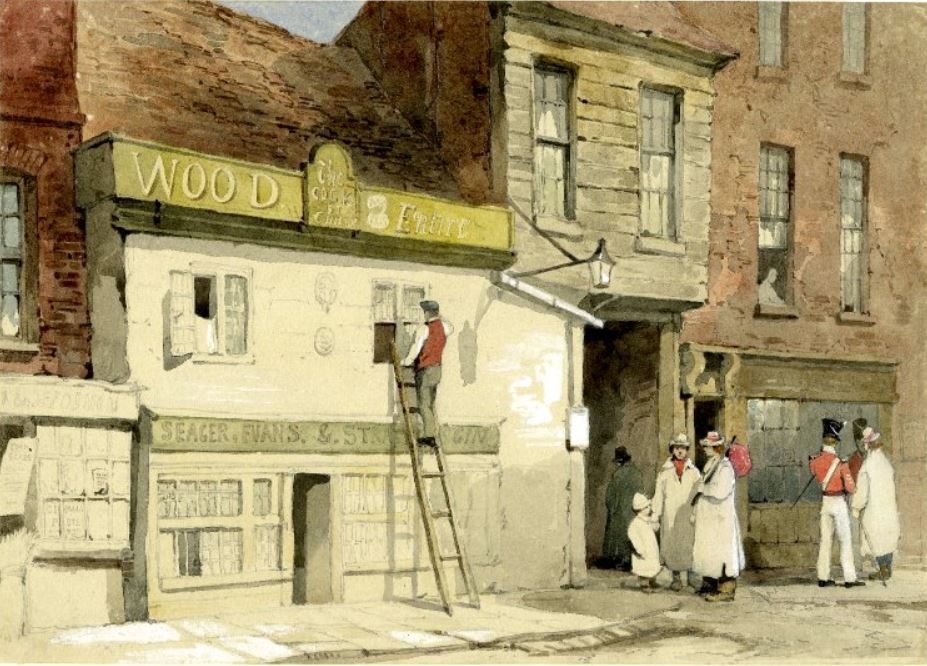

The Cock Inn was one of London’s very old inns:

Image dated 1845 © The Trustees of the British Museum

According to Stow, the original Cock, or Cock and Tabard existed as far back as the reign of Edward III (1327 to 1377), and workmen were paid at the Inn during the building of Westminster Abbey. This original Inn may at some point have been demolished, and a new Inn, the Cock, was built on the opposite, north side of the street, which would be the location marked on the map.

Timber was reused from the original Inn to build the new, and there is a story in Old and New London which was also reported in the London Evening Standard on the 9th January 1854:

“DISCOVERY OF ANCIENT GOLD AND SILVER COINS – On Saturday morning, while some workmen were taking down some outhouses belonging to the well-known Old Cock and Tabard Inn, Tothill-street, Westminster, in the occupation of Mr Flixton, they came in contact with a large oak beam, which was hollow in the centre, when to their great surprise, they discovered a very large quantity of gold and silver coins, besides other antiquities of the reign of Henry V and Henry VII. The men, not knowing the real value of these coins, which are in a state of very good preservation, sold several to parties in the neighbourhood for a few pots of beer. Fortunately Messrs. J.C. Wood and Co., the eminent brewers, of Victoria-street, Westminster, hearing of the discovery, got possession of the remainder; and it is supposed by antiquaries and others competent of judging that they must have remained in the place where they were found for 500 or 600 years.”

The newspaper report uses the old name for the Inn, and there does seem some confusion regarding whether the inn on the northern side of Tothill-street was the original inn, or whether it was a rebuild of an inn that had existed on the opposite of the street, Old and New London states that the large oak beams were from the original inn, and it was common to reuse building materials.

The Cock Inn was demolished in 1873 to make way for the development of the Royal Aquarium – a sad fate of an inn that was probably around 500 years old.

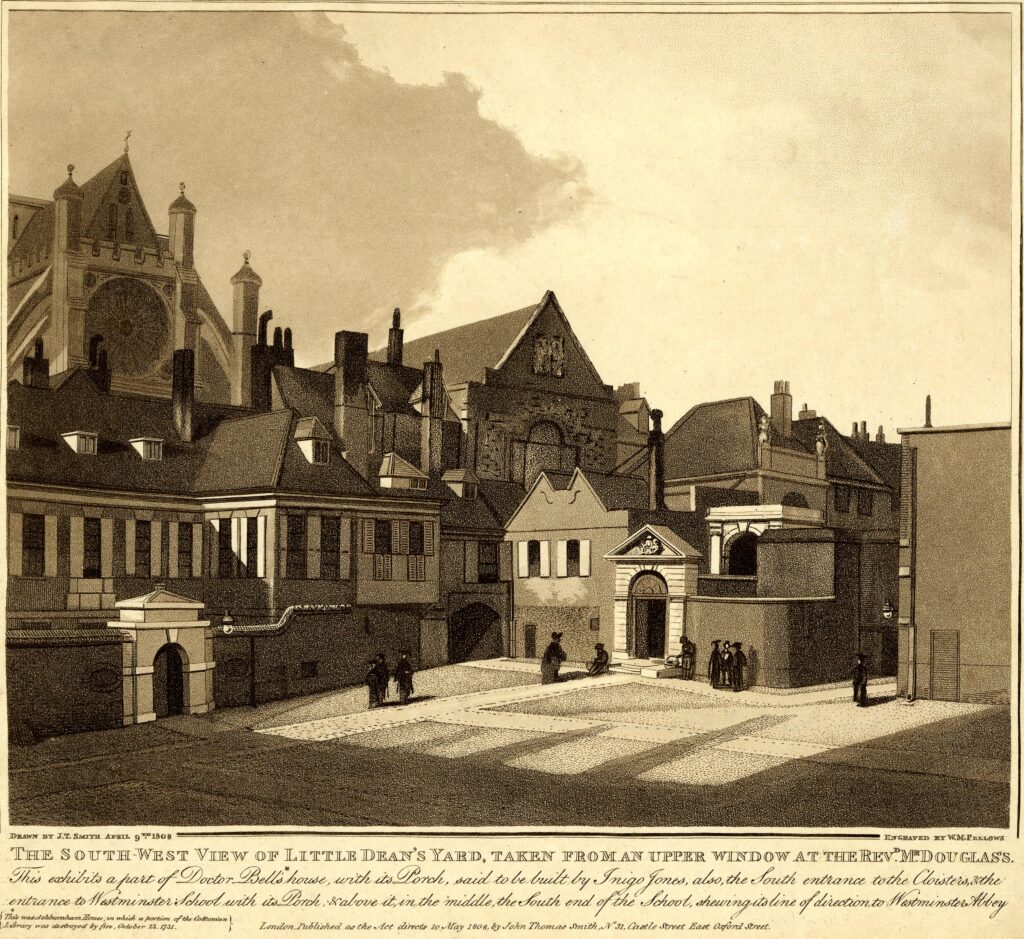

The yellow oval is around another building that had a longer life than the Royal Aquarium, but has since been demolished and replaced by a very different building.

This is the Westminster Hospital:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_02_0579_5846C

The above photo is dated 1913 and shows the Westminster Hospital facing onto the yard at the entrance to Westminster Abbey. The front of the Methodist Central Hall can just been seen on the left of the photo.

The site of the Westminster Hospital is today occupied by the Queen Elizabeth II Centre, and the grass space in frount.

The origins of the Westminster Hospital date back to 1716. The founders (Henry Hoare from the Hoare banking family, William Wogan, a religious author, a wine merchant, Robert Witham and the Reverand Patrick Coburn) were concerned about the very unhealthy conditions along the north bank of the Thames in Westminster. The area was subject to frequent flooding and the land was marshy.

In 1719, the Westminster Infirmary opened in a small house in Petty France, as a voluntary hospital, dependent on donations for all running costs.

The Westminster Hospital opposite the Royal Aquarium was the fourth version of the hospital, as it expanded and moved around Westminster as property became available.

Built in 1834 with an initial capacity of 106 in-patients, the hospital expanded over the years, with the additional of nurses accommodation and a medical school.

The first operation under general anesthetic was performed at the Westminster Hospital in 1847. One of the Doctors at Westminster Hospital was Dr. John Snow, who was responsible for tracking down the source of a cholera outbreak in Soho in 1854.

Within 10 days there were a large number of fatal cases of cholera within a small radius of the junction of Broad Street (now Broadwick Street) and Cambridge Street (now Lexington Street).

John Snow worked meticulously on tracking down all those who became infected to discover any common link between infections, and he gradually came to the conclusion that the common source was a water pump close to the junction of Broad and Cambridge Street’s. To confirm that this was the source, he also tracked locals who were not infected to find out where they sourced their water and in all cases it was a different source to the water pump.

He had some trouble trying to convince officials that the pump was the source, but after the pump handle was removed, cases stopped appearing. In his report to the Medical Times and Gazette, he wrote:

“I had an interview with the Board of Guardians of St. James’s parish, on the evening of the 7th, and represented the circumstances to them. In consequence of what I said, the handle of the pump was removed on the following day. The number of attacks of cholera had been diminished before this measure was adopted, but whether they had diminished in a greater proportion than might be accounted for by the flight of the great bulk of the population I am unable to say. In two or three days after the use of the water was discontinued the number of fresh attacks became very few.

The pump-well in Broad-street is from 28 to 30 feet in depth and the sewer which passes a few yards away from it is 22 feet below the surface. the sewer proceeds from Marshall-street, where some cases of cholera had occurred before the great outbreak.

I am of the opinion that the contamination of the water of the pump-wells of large towns is a matter of vital importance. Most of the pumps in this neighbourhood yield water that is very impure; and I believe that it is merely to the accident of cholera evacuations not having passed along the sewers nearest to the wells that many localities in London near a favourite pump have escaped a catastrophe similar to that which occurred in this parish. ”

An early example of the importance of track and trace, and of listening to experts.

A pub called John Snow is now on the corner of Broadwick and Lexington Street, close to the original location of the contaminated pump.

Back to the Westminster Hospital, and the buildings opposite Westminster Abbey remained open until 1939, when a new and enlarged hospital building was completed at St. Johns Gardens.

Westminster Hospital remained at St Johns Gardens until 1993, when the buildings of the 5th version of the hospital closed, and reopened as the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital on Fulham Road.

The hospital buildings opposite Westminster Abbey remained for a number of years, and there were plans to build a new Colonial Office on the site. The following is an illustration of what the Colonial Building could have looked like.

There were plans for the site to become an open space, or alternative government offices, however it was not until 1975 that the plan for a conference centre was approved, and construction of the current building that occupies the site started in 1981 with the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre opening in 1986.

There is one final site marked on the map by the blue circle. This is the location of Cockpit Steps, which I wrote about here.

I started this post with the theme of how London’s buildings change continuously, and the Royal Aquarium, Westminster Hospital building and a 500 year old pub are now just historical footnotes. But they all hold a wealth of history, whether the story of James Gordon pulling his wheelbarrow from Dundee to feed his family, hidden treasure in centuries old beams, or a pioneering doctor who found the source of a cholera outbreak in Soho.

The same will apply to nearly every building across London today, at some point they will also become a historical footnote as the city responds to continuous change, and reinvention.

alondoninheritance.com