As well as publishing my father’s photos and tracking down their location, one of my aims with this blog is to give me a push to get out and explore more of London’s fascinating history, locations such as Tilbury Fort.

The history of London is indelibly linked with the surrounding countryside, towns and villages, and what has always interested me is how London’s influence spreads so far beyond the original walled city. Central to London is also the River Thames, without which London would not have come into existence and developed in the way that it has. The influence of the Thames is often somewhat neglected these days, frequently just a scenic backdrop to the developments alongside.

If you follow the river from central London towards the estuary there are two forts at Tilbury that have played a key role in protecting both the River Thames and London from a range of threats over the centuries.

Tilbury today is best known for the Tilbury Docks (the first major commercial docks this far east of London, opened in 1886), as a cruise terminal and with a ferry across the river to Gravesend, however Tilbury has also been the location since Tudor times of a Fort to protect the River Thames and the approaches to London.

The River Thames provided access directly to the City of London, it carried all the import and export trade to the docks, and along the banks of the river were many of the yards that constructed and equipped the countries naval and commercial shipping (for example the Woolwich Arsenal and the Deptford Dockyards).

The relative ease with which these could be attacked was highlighted in June 1667 when a Dutch fleet entered the Thames estuary and sailed up the River Medway to attack the naval shipping at Chatham, burning a number with fire ships, capturing and sailing away a number of others. After this event, the diarist John Evelyn visited Chatham and wrote “a Dreadful Spectacle as ever any Englishman saw and a dishonour to be wiped off”.

The construction of the first Tilbury Fort was a result of Henry VIII’s separation from the Church of Rome. Fearing attack from the Catholic powers of Europe, five “blockhouses” were built along the Thames at West and East Tilbury, Higham, Milton and Gravesend. The blockhouses had artillery installed on the ground floor and the roof, aligned to provide crossfire across the Thames in conjunction with the blockhouse on the opposite side of the river.

Any attacking force moving up the river would have to pass these five blockhouses, all firing multiple artillery rounds.

Fortunately for Henry VIII, there were no attacks along the river so the blockhouses remained untested. When Mary 1 became queen in 1553, the papal supremacy was restored so the threat of invasion from Catholic Europe was lifted. The blockhouses were disarmed and left.

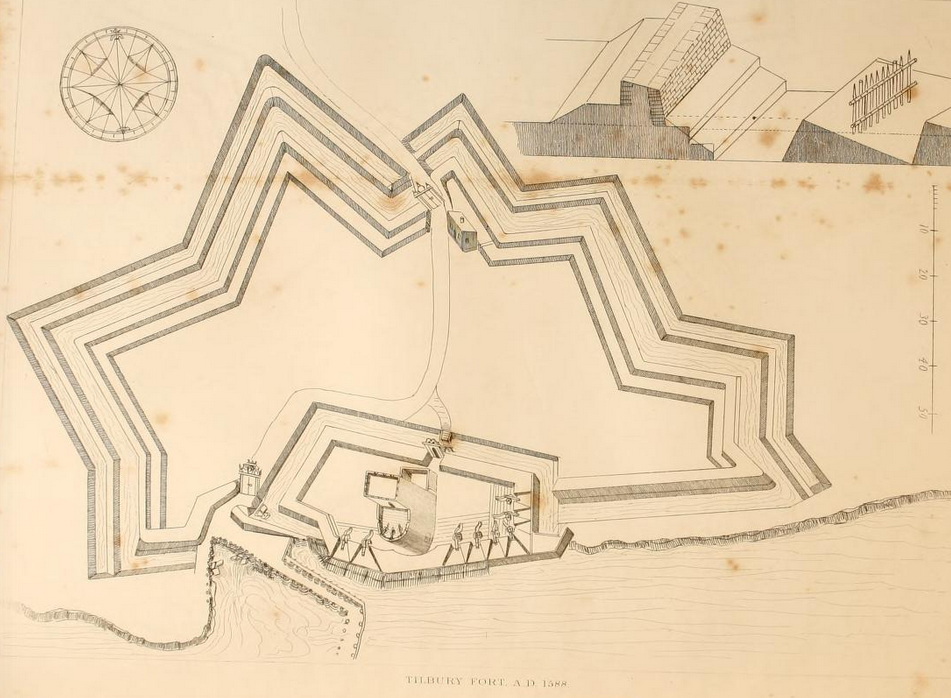

When Elizabeth became queen in 1558 the Tilbury blockhouse was repaired and re-armed with additional reinforcements during the threat from the Spanish Armada in 1588. The following plan from The History of the Town of Gravesend by Robert Peirce Cruden shows the site in 1588 with the blockhouse in the lower centre surrounded by embankment defences.

The site was completely rebuilt after the 1667 Dutch attack, with construction commencing in 1670 and completion in 1685 resulting in one of the most powerful forts in the country, equipped to protect the City of London, the docks and industries along the river from any attacking force that ventured up the Thames. The new Tilbury Fort also included major defences to protect the fort against any land based attack.

It is this Tilbury Fort which is still substantially in existence today.

Approaching Tilbury Fort today, walking alongside the River Thames, entrance is through the ornate Water Gate, completed around 1682. The plaque above the main entrance reads “Carolus II Rex” – Charles 2nd and there was probably a statue of the King in the niche above.

The Water Gate stands out well in this 1849 painting by Clarkson Frederick Stanfield titled Wind Against Tide (source: commons.wikimedia.org – click on image for original link) showing the fort on the right with shipping on the river experiencing rather rough conditions.

On entering the fort, the large parade ground gives an indication of how many soldiers would have been stationed here at the height of operations. Throughout the life of Tilbury Fort, numbers were in the range of between 100 and 300.

The officers barracks are at the back of the parade ground.

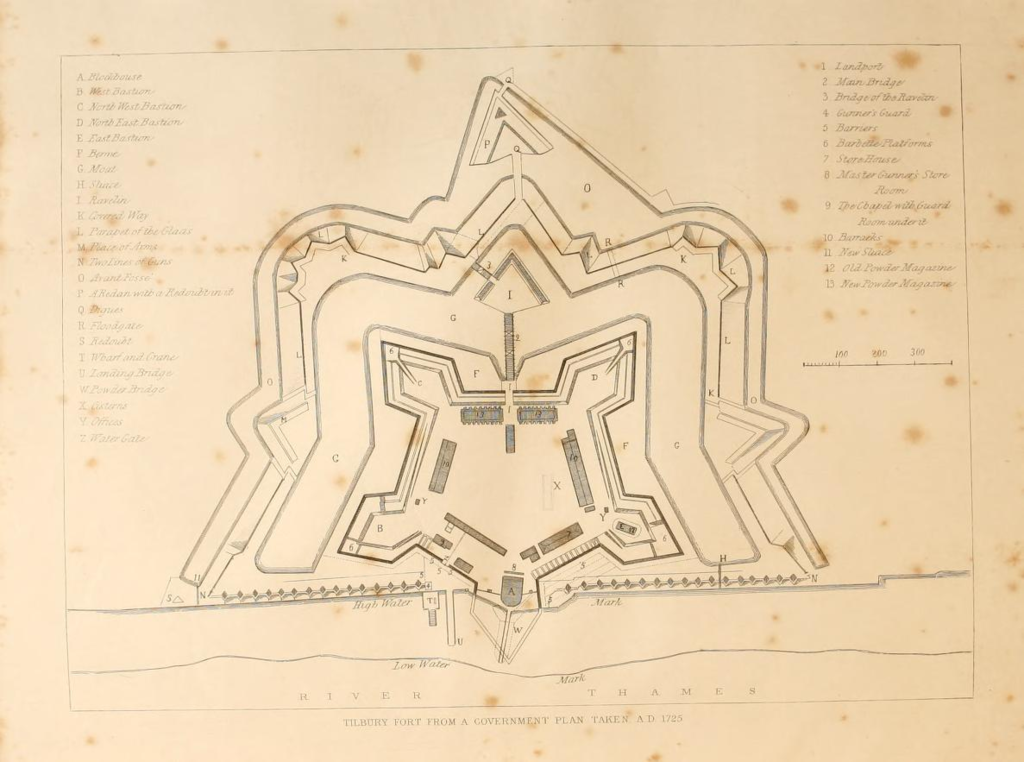

The layout of the rebuilt Tilbury Fort and the considerable defences can be seen in this plan of the fort in an engraving from a 1725 plan from The History of the Town of Gravesend by Robert Peirce Cruden. The Water Gate is at the lower centre of the plan. Note the markings for low and high water showing that at high water the river originally came up to edge of the fort.

The layout of the rebuilt Tilbury Fort and the considerable defences can be seen in this plan of the fort in an engraving from a 1725 plan from The History of the Town of Gravesend by Robert Peirce Cruden. The Water Gate is at the lower centre of the plan. Note the markings for low and high water showing that at high water the river originally came up to edge of the fort.

It is hard to get an impression of the overall scale of the fort from ground level. The following photo is from the Britain From Above website and was taken in May 1934. Tilbury Fort can be seen at the lower right of the photo. The defensive moat that runs around the fort was partially dry at the time and shows up as white. The Tilbury Docks can also been seen, along with a considerable amount of shipping in the river between Tilbury and Gravesend on the opposite shore.

As well as defending the river, Tilbury was also a mustering point for soldiers from London.

As well as defending the river, Tilbury was also a mustering point for soldiers from London.

In March 1587, Queen Elizabeth 1st requested the City to provide a force of 10,000 men, fully armed and equipped. The following table lists the numbers of men from each individual ward:

| Farringdon Ward Within | 807 | Broad Street | 373 |

| Bassishaw | 177 | Bridge Ward Within | 383 |

| Bread Street | 386 | Castle Baynard | 551 |

| Dowgate | 384 | Queenhithe | 404 |

| Lime Street | 99 | Tower Street | 444 |

| Farringdon Without | 1264 | Walbrook | 290 |

| Aldgate Ward | 347 | Vintry | 364 |

| Billingsate | 365 | Portsoken | 243 |

| Aldersgate | 232 | Candlewick | 215 |

| Cornhill | 191 | Cripplegate | 925 |

| Cheap | 358 | Bishopsgate | 326 |

| Cordwainer | 301 | ||

| Langbourne | 349 | ||

| Coleman Street Ward | 229 | Total | 10007 |

These numbers give some idea of the population density of each of the wards, The Earl of Leicester was in command at Tilbury and received 1000 of the London force, only on the condition that they brought their own provisions.

The description of their arrival at Tilbury gives the impression of London men being dressed for show, rather than for work and fighting:

“The London men wore a uniform of white with white caps and the City arms in scarlet on back and front. Some marched in companies according to their arms. Their officers rode beside the men dressed in black velvet. They were preceded by billmen, by a company of whifflers (trumpeters) and in the midst marched six Ensigns in white satin faced with black sarsenet and rich scarves The dress of the officers and men was just as useless and unfit for continued work as could well be devised. It is melancholy to find that the Earl of Leicester who was in command at Tilbury held a very poor opinion of the London men.”

It was also at West Tilbury that Elizabeth 1st met the Earl of Leicester on the 8th August 1588 and the following day addressed the troops with the speech:

“And therefore I come amongst you at this time, not as for my recreation or sport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of the battle, to live or die amongst you all, to lay down, for my God, and for my kingdom, and for my people, my honor and my blood, even the dust. I know I have the body of a week and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England, too; and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realms; to which, rather than any dishonour should grow by me, I myself will take up arms.”

Although there are a number of different versions of this speech, the evidence appears to be strong that Tilbury was the location where Elizabeth 1st addressed her troops at the time of the Armada.

For those stationed at Tilbury Fort, it must have seemed a remote and barren location. Today, the fort is surrounded by docks and a power station, but up to the building of the docks the area was mainly barren, flat land. To get an idea, the following photo from 1938 is also from Britain From Above and shows the fort in the bottom right hand corner with only a water treatment works before flat fields stretch into the distance. Much of this is now occupied by Tilbury Power Station.

At the far end of the parade ground are the officers barracks. These were originally built in 1685, rebuilt in 1772 with further modifications during the 19th century. These barracks would have been used by the senior officers along with their families. Unfortunately the solders barracks were demolished in the early 1950s. They also faced onto the parade ground.

There is an interesting connection between Tilbury and Greenwich. When Charles II approved the construction of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, the King allowed £500 towards the new building, together with a supply of bricks from Tilbury Fort, where there was a spare stock, so some of the fabric of both locations is from the same stock of bricks.

As well as acting as a mustering points for troops, the main function of the fort was to protect the river.

Tilbury is the point in the Thames where the river starts to narrow on the approach to London, so it is an ideal location to site guns to fire at any invading ships attempting to move up river. Gun emplacements are arranged along the fort providing firing points looking across the river with Gravesend in the background:

Shipping still passes Tilbury Fort, but of a very different type from when the fort was in use:

The fort also stored a considerable amount of gunpowder and munitions, both for use in the fort and as a general reserve for the army. Two magazines held large quantities of gunpowder. These are the only powder magazines to remain in Britain from the early 18th Century. Very strong, with a large blast wall around the perimeter.

As well as gunpowder, munitions were stored in tunnels constructed under the earthworks. One of the tunnels leading to storage rooms for artillery shells and other munitions:

One of the storage rooms leading off the tunnel:

During the 18th and early 19th centuries there was the occasional threat of an attack on London via the river, although the majority of wars were being fought on the continent or at sea.

During the 18th and early 19th centuries there was the occasional threat of an attack on London via the river, although the majority of wars were being fought on the continent or at sea.

Tilbury Fort was permanently manned with numbers being ramped up or down dependent on the perceived threat level. The troops at the fort were also responsible for defending the fort and surrounding area from any land based attack. The fort was very well protected from land based attack with a series of moats and land defences. To the rear of the fort, a reconstructed bridge leads across to one of the island defensive locations, then on to the flat lands north of the river.

Soon after the Jacobite rebellion of 1745-6 Tilbury Fort was used as a prison for survivors of the rebellion whilst they waited for trial in London. Off 303 that sailed from Inverness, 268 survived to Tilbury. They were imprisoned in the gunpowder magazines in such dreadful conditions that a further 50 died. After trial in London in 1747 they were either executed or transported to Barbados and Antigua to work on the sugar plantations as slave labourers.

Another view inside the fort. The Water Gate is on the left with the guard-house and chapel on the right:

The gunpowder held at the fort was used for many purposes. In May 1838 the Brigg, William had been run down by a steamer opposite the fort and was causing an obstruction in the river. The people of Gravesend petitioned the Government to have it removed and a party of sappers and miners led by a Colonel Paisley arrived to sink a large amount of powder under the wreck by means of a diving bell. A special fused pipe led to the surface allowing the fuse to be lit from the surface and the sappers to get back to shore in time. There was an “awful explosion” with “waters rising mountains high followed by clouds of black coal and pieces of wreck”.

Tilbury Fort continued in use throughout the 19th century with occasional upgrades as technology provided new and more efficient guns and threats changed, however by the start of the 20th century naval technology had increased so much that large shore forts along the river had become obsolete and naval protection of the Thames was considered a more effective form of defence.

The fort continued to be used for storage and also as a transit centre for troops, a key role during the 1st World War, given the adjacent port of Tilbury.

During the 2nd World War, the fort had a brief role as an anti-aircraft operations centre, controlling the fire from guns along the river.

Tilbury Fort finally ceased any military role in 1950 when it was transferred into the Ministry of Works as a historic monument and the fort is now in the care of English heritage.

This is absolutely fascinating David – I’ve lived in London all my life and had no idea that this was here. I sense a field trip with my military history -loving husband very soon….

Thanks Vivienne, it is a surprising location, now sandwiched between Tilbury Docks and Power Station, but well worth a visit. There is another fort (a post soon) in East Tilbury (Coalhouse Fort). All part of the fascinating history of the Thames.

I used to swim in the moat as a teenager and we often squeezed through the fence and played in the fort, until chased out by the warden. There is now a path that runs along the river to Coalhouse fort (NCN 13 I believe). The power station has gone and at present a ro-ro terminal is being built there as part of Tilbury 2 – an extension of the docks.