Limehouse Hole Stairs are one of the very old stairs between the land and the river. They are towards the eastern edge of Limehouse, in an area once known as Limehouse Hole, where the river turns south on its journey around the Isle of Dogs.

Today, the stairs are a wide and well maintained set of steps leading down from the walkway alongside the river, towards a very roughly rectangular area which is accessible when the tide is low:

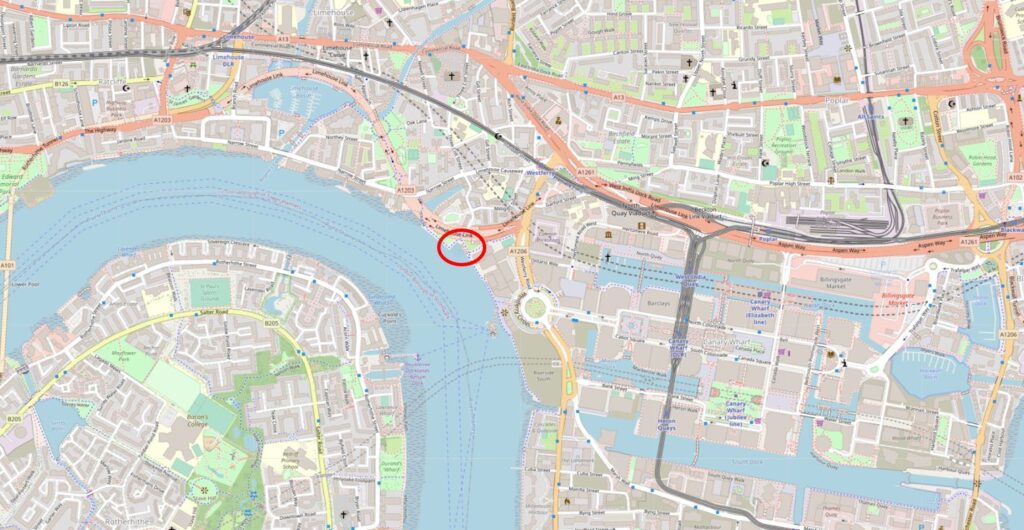

The location of Limehouse Hole Stairs is shown by the red oval in the following map (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

On the foreshore at low tide:

The foreshore at Limehouse Hole Stairs has large sandy patches along with plenty of stone and brick that has found its way into the river from the buildings and infrastructure that once lined the Thames.

If you look closely, it is interesting how similar items can be found in lines along the foreshore. They were left when the tide went out, and form a line across the sand. I have no idea of the mechanism that leaves them in a line rather than randomly scattered, and on the foreshore at Limehouse Hole Stairs, a line of green glass / plastic / minerals (not sure what they were), was stretched across the sand:

The Port of London Authority list of the steps, stairs and landing places on the tidal Thames has very little information on Limehouse Hole Stairs, just recording that they were in good condition, with stone and concrete steps and in use. The PLA had not recorded whether the stairs were in use in their two key recording years of 1708 and 1977.

The stairs are old, but the stairs we see today are very different to what was there prior to the redevelopment of the area in recent decades, which I will show later in the post.

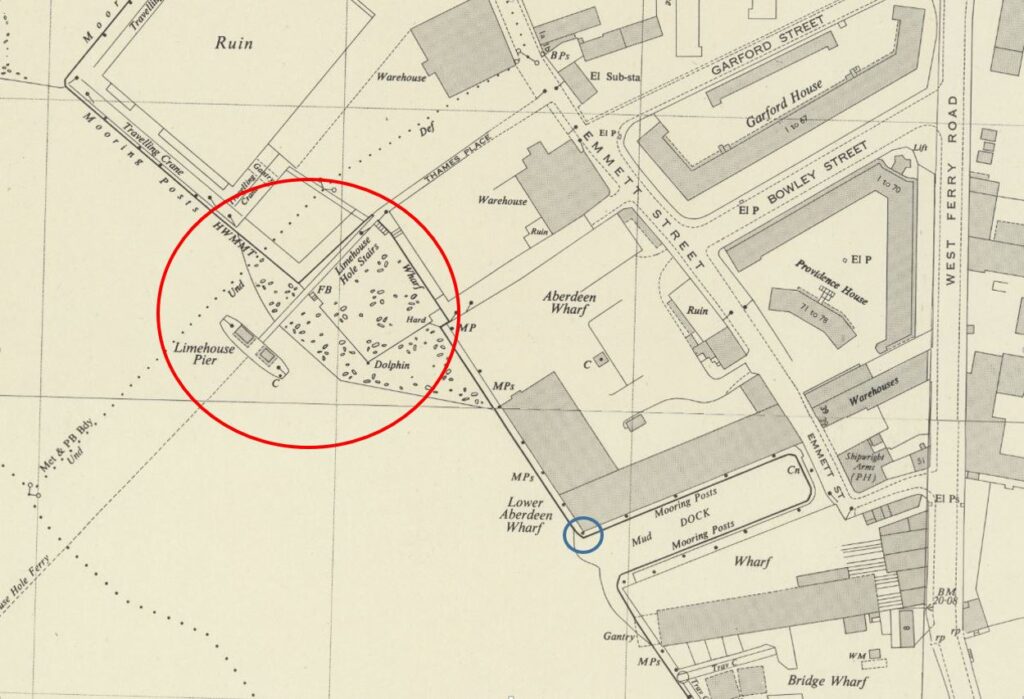

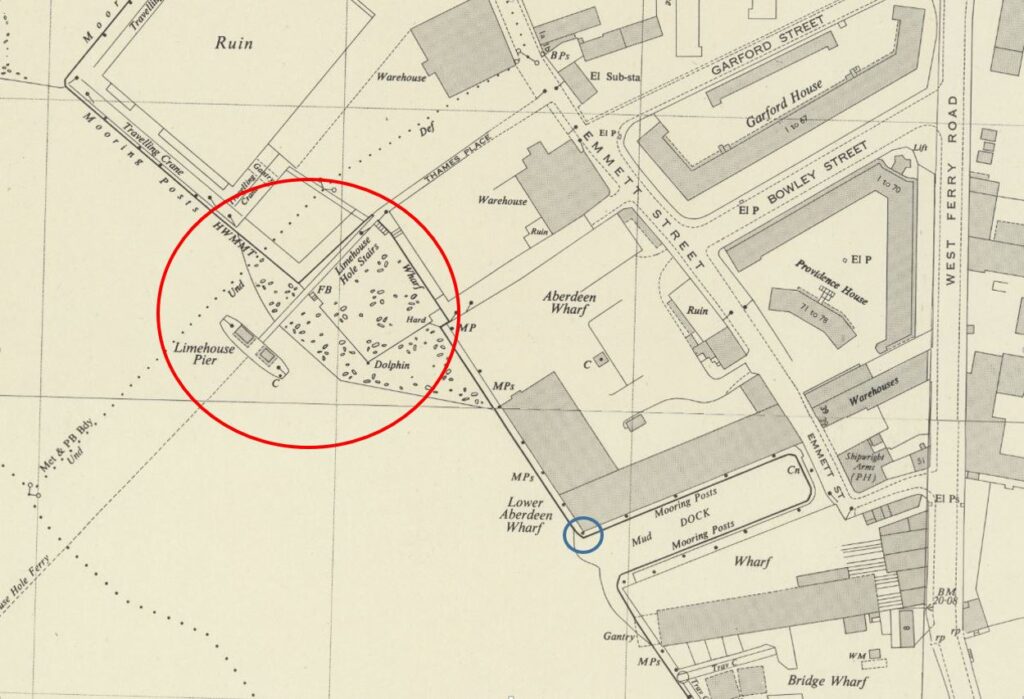

The following extract from the 1949 revision of the OS map shows the location of Limehouse Hole Stairs (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“)..

There is an area of foreshore that dries when the tide is low shown mainly within the red circle. Limehouse Pier extends into the river. Follow the pier back to land, and in the corner is Limehouse Hole Stairs.

You can also see in the above map, a line forming two sides of a square, with the river walls forming the other two sides. The two lines running across the dried foreshore in the map were a wooden surround, parts of which can still be seen today, as I will show later.

I will come to the relevance of the blue circle later in the post.

This area has a complicated naming history.

Written references to the stairs date back to the early 19th century, although these do not explicitly name Limehouse Hole Stairs. A typical advert in February 1807 was for the Schooner Anne which was for sale and could be seen “lying at Limehouse Hole, opposite the stairs”.

The name Limehouse Hole is also a bit of a mystery. It may refer to a form of small harbour or dock, although I find this unlikely as the larger Limekiln Dock is within the area traditionally known as Limehouse Hole.

I did wonder if the name referred to a hole in the river, perhaps a particularly deep part of the Thames, however in the area known as Limehouse Hole, the bed of the river is of a depth that is normal for much of this stretch of the river, typically around 6 metres deep at the lowest astronomical tide.

There is though a strange depression in the bed of the river not far to the west, in the middle of the river opposite the entrance to Limehouse Dock, where the river descends from a depth of 5.5 metres to a depth of 11.4 metres, all within a small area of the Thames.

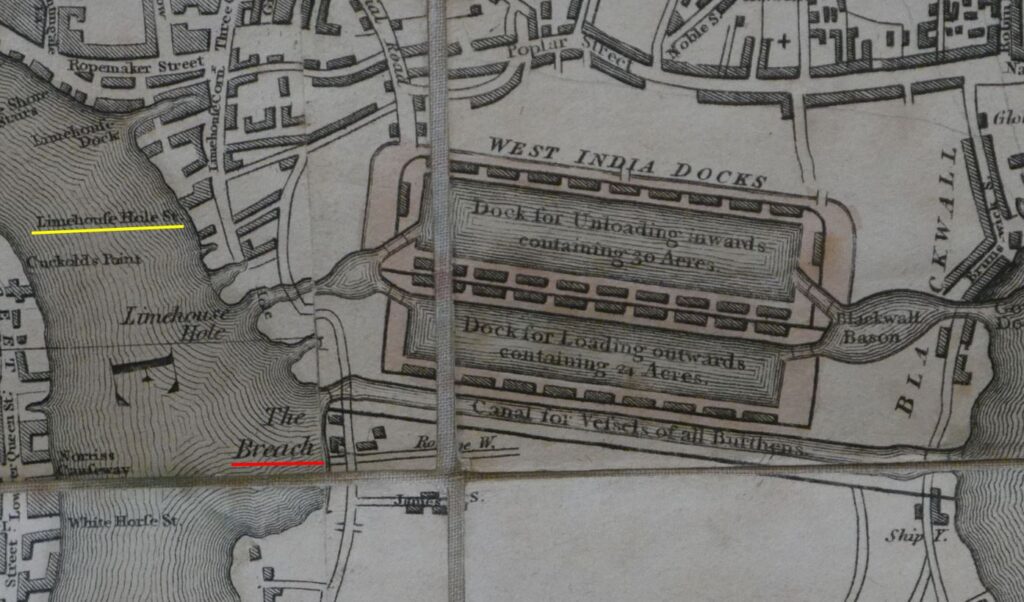

To add to naming confusion, if we look at Rocque’s map from 1746, there are stairs in the rough location of Limehouse Hole Stairs, however Rocque calls then Limekiln Stairs, and he also names this stretch of the river Limekiln Holes rather than Limehouse Hole, so perhaps the name refers to some aspect of the Limekiln industry, and as this industry declined, the name changed from Limekiln to Limehouse Hole.

The Survey of London does though state that the name Limehouse Hole was in use for this section of the river by the seventeenth century, so perhaps Rocque was confused with the Limekilns and Limekiln Dock, or in the 18th century there were different names in use.

The extract from Rocque’s map is shown below:

The first references to the full name of Limehouse Hole Stairs start to appear around 1817, and there are multiple references in the 1820s onwards. All the usual events that make their way into the papers – accidents on the river, ships for sale, fires in the buildings by the stairs, rowing competitions, and tables of rates for Watermen to charge to row passengers along the river.

In the OS map shown above, there is a pier coming out from Limehouse Hole stairs. The earliest reference I can find to the pier dates from 1843, when there was an article in the November 5th edition of The Planet recording a court case, where “On Tuesday, Jonathan Bourne, a waterman, and one of the proprietors of the floating-pier at Limehouse Hole stairs, appeared to answer a charge of carrying passengers in his boat on Sunday, in violation of the rights and privileges of William Banks, the Sunday ferryman. The real question in dispute between the parties was as to the right of the watermen owning the floating pier to convey passengers to and from the Watermen’s Company steamers which stop there. When the tide is low there is not sufficient water for the steamers to come alongside the outer barge of the pier, and the watermen row the passengers to the steamers, and vice versa, but no money is taken.”

From the article, it appears that the pier was owned by a group of watermen. The article also shows how watermen were regulated, and had specific rights covering what they could do, and when. I did not know that the Watermen’s Company ran steamers on the river. This must have been a far more efficient way of conveying passengers along the river, rather than rowing as watermen in previous years would have done. Also, an early version of the Thames Clippers that provide the same service today.

The pier seems to have disappeared by the 1860s, as in the East London Observer on the 1st of May, 1869, there was a report on a public meeting of the parishioners of Limehouse “to consider what action should be taken in obtaining the construction of a pier on the Thames, for the convenience of the inhabitants of Limehouse”, and that “there were many persons who would far rather go to the city by boat than either rail or bus”.

A new pier was needed because “the old pier was never under the management of the Thames Conservators, but under that of the watermen, who let it go to ruin”.

A new pier was built in 1870 and this second pier lasted until 1901, when it was removed for the construction of Dundee Wharf, and a couple of years later, the London County Council built the third pier on the site.

Getty Images have some photos of this third iteration of the pier, with the following photos showing the pier stretching out across the foreshore, with Dundee Wharf in the background, on the left. Click on the arrows to the sides of each photo to see all images of the pier in the gallery. (If you have received this post via email, the photo may not be visible due to the way code embedding works. Go to the post here https://alondoninheritance.com/ to see the photo).

The photos show the wooden surround which was shown in the earlier OS map. The photo helps with the purpose of this surround, as it presumably held back a raised area of the foreshore to create a reasonably level space for barges and lighters to be moored.

The Survey of London states that this third pier “was removed by the PLA in 1948, but the stairs and Thames Place, though closed off in 1967, survived until 1990”. The survival of the stairs until 1990 presumably refers to the version of the stairs prior to that which we see today.

The result of multiple piers, along with the wooden surround to the area, means that there are still remains on the foreshore which we can see today:

Including plenty of loose timbers which may have been washed here from other locations along the river:

And when the tide is low, we can still see the wooden surround which once enclosed a flat area of the foreshore as can be seen in the Getty photo above:

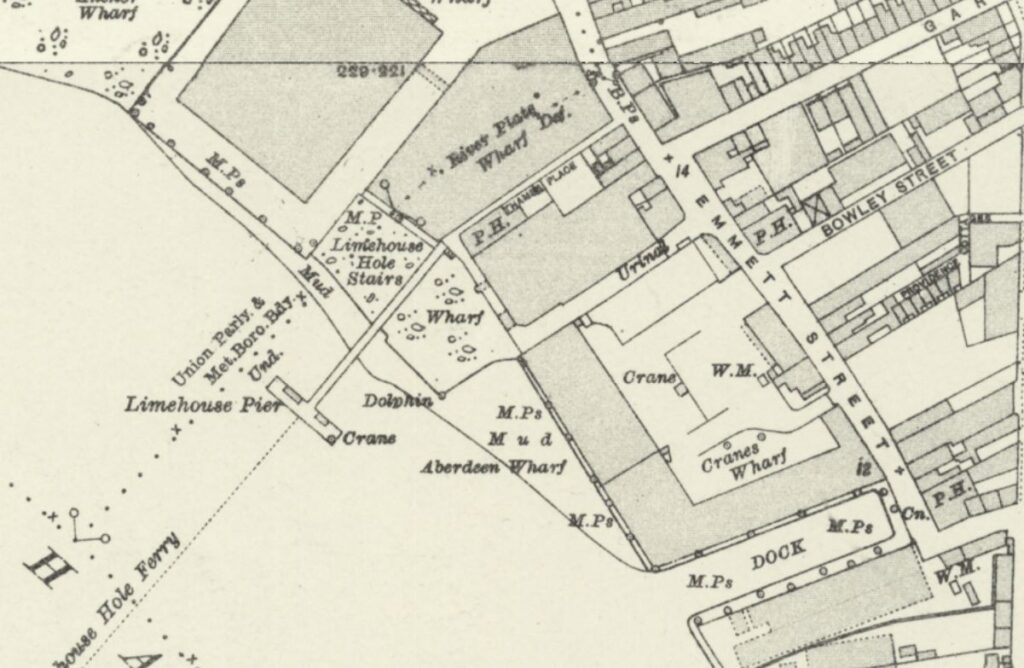

The following 1914 revision of the OS map shows Limehouse Hole Stairs and the pier, and also shows Limehouse Hole Ferry running across the river from the pier. This was a ferry to the opposite site of the river which landed at Horn Stairs, and which provided a fast way of crossing the river, rather than having to travel to either the Rothehithe or Blackwall Tunnels (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

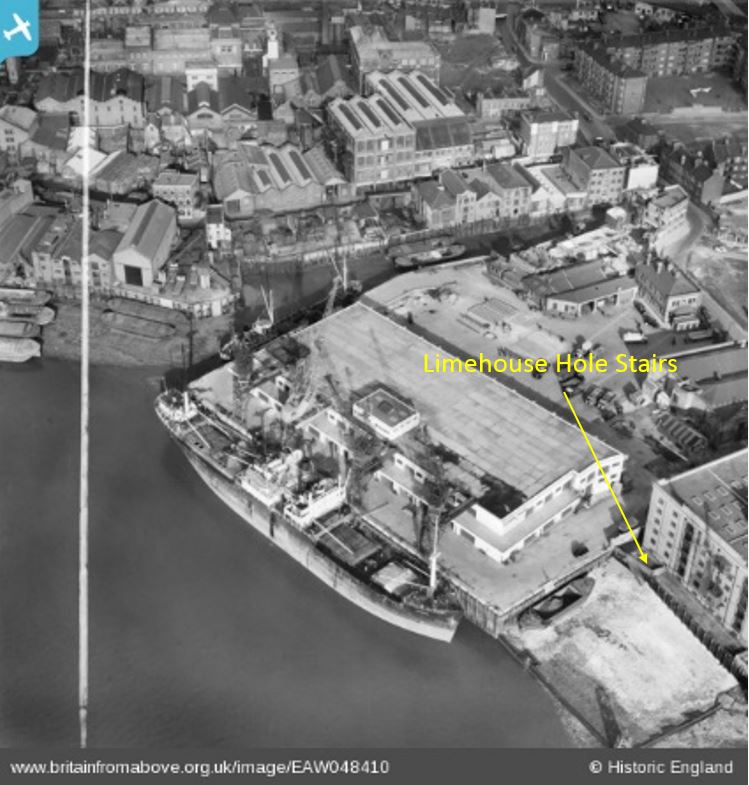

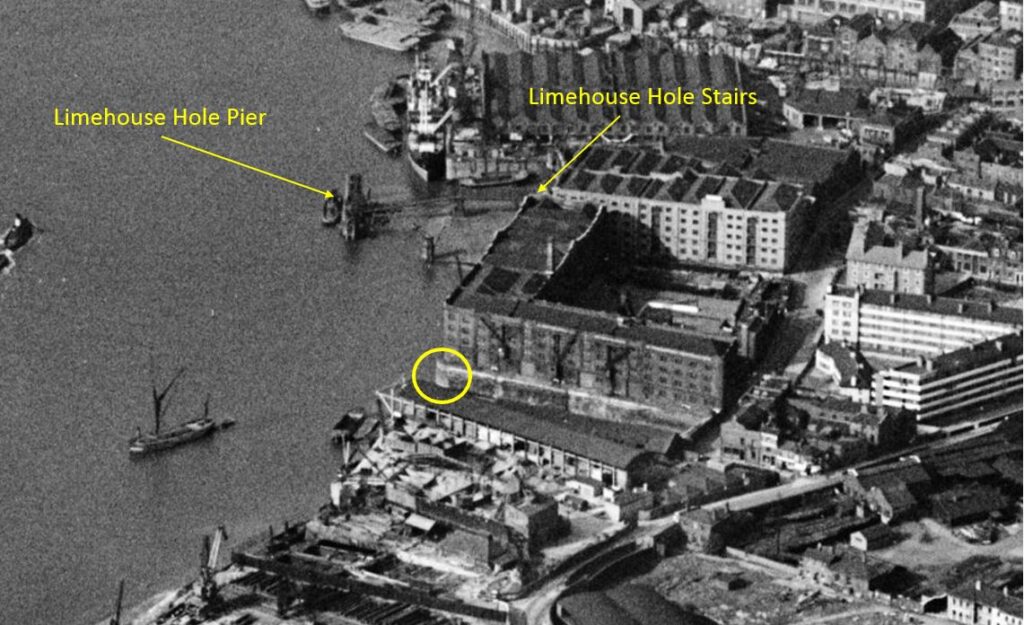

The following photo from Britain from Above shows the site in 1953 when the pier had been removed. I have marked Limehouse Hole Stairs, which at the time was simply wooden steps leading down to the foreshore. To get a closer view, the photo can be found here.

The pier had been removed just a few years before the above photo. Limekiln Dock runs inland towards the top of the photo, and, along with the shape of the river wall where Limehouse Hole Stairs is located, is the only feature that survives today. Almost every single building has disappeared.

Although Limehouse Hole Pier has gone, there is another pier, a short distance to the south, where the Canary Wharf pier can be found today, which provides access to the Thames Clippers, providing a similar function to the old steamers that once docked at Limehouse Hole pier:

Looking north from Canary Wharf pier, and there is another feature that survives. In the following photo, looking towards the location of Limehouse Hole Stairs, there is a straight row of metal piling, followed by a brick wall:

With a closer look, we can see that the brick wall turns inwards:

Returning to the 1949 revision of the OS map, I have marked the curved brick wall in the above photo, by a blue circle in the following map:

The curved brick wall was at the northern side of the entrance to a dock that ran alongside Lower Aberdeen Wharf.

The wall today looks as if it continues in land and I would love to know how much of the old dock, and the walls that once surrounded the dock, survive under the modern walkway that has been built as part of the redevelopment of the area.

We can also see the dock in an aerial photo, again from the Britain from Above web site, and dating from 1938:

I have highlighted the corner wall we can see today in an extract from the above photo, and have also marked the stairs and pier:

As well as Limehouse Hole Stairs, the other part of the title of the post is “the Breach”.

Much of the Isle of Dogs, and indeed much of the land alongside the Thames, is low lying, and over the centuries, it has been very common for there to be floods during high tides.

As London grew, and trade along the river developed, land was reclaimed, and river walls were built, but until the 20th century, these walls were often not of the height and strength we see today.

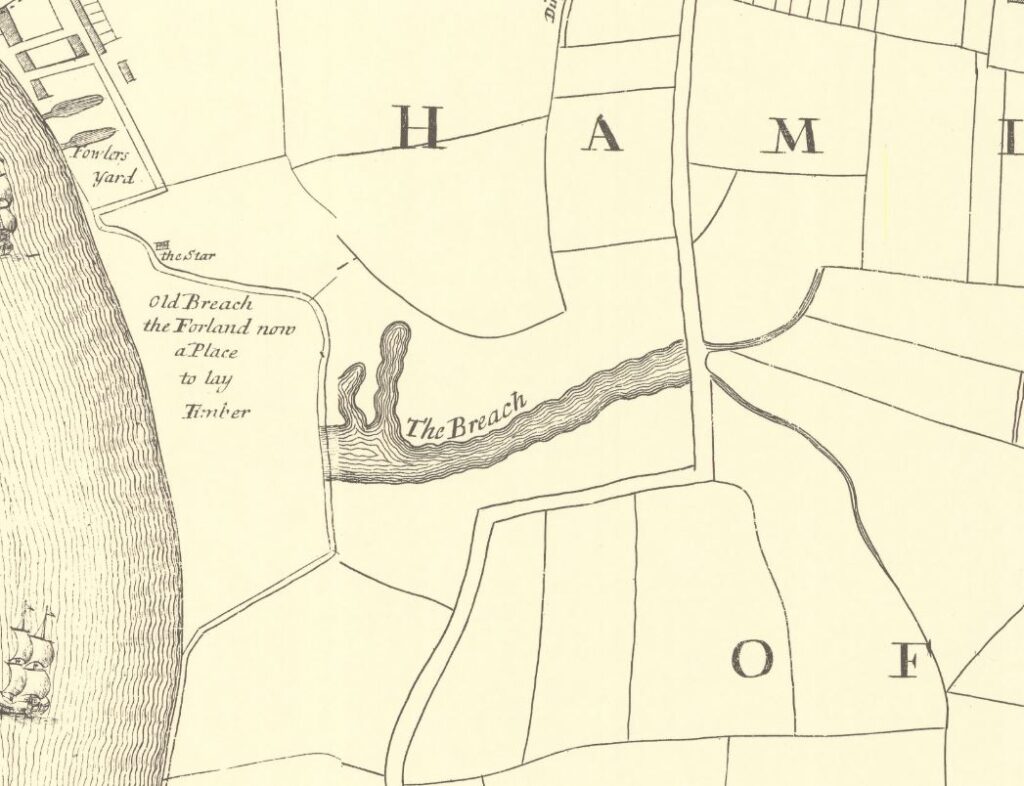

Nor far south of Limehouse Hole Stairs is an area of land where the river wall was breached, and was flooded, or in a state of marsh, for very many years. This was known as “The Breach”, and was shown on maps, including Rocque’s 1746 map, where it can be seen with a road running around what appears to be an area of marsh:

There is also a water feature in the above map called the “Poplar Gut”, and both this and the Breach were mentioned in an article in the East London Observer in 1903, when “Pepys in his diary under date of 23rd March, 1660, mentions that he saw the great breach which the late high water had made, to the loss of many thousands of pounds to the people about Limehouse. In Gascoyne’s map, the spot is marked by the explanation ‘Old Breach, the Foreland, now a place to lay timber’ and ‘The Breach’ is applied to what was more recently known as the Poplar Gut”.

The reason why the Breach happened where it did was down to the natural erosion of the land by the river at this particular point in its meander around the Isle of Dogs.

In time, and without any human intervention, the Thames would have cut through the northern section of the Isle of Dogs, leaving the part of the river around the south of the Isle of Dogs as an Oxbow Lake. The Thames has made subtle changes to its course over the centuries, and it is only in recent years that we have effectively put the river into a concrete and banked channel, and limited the natural forces of erosion.

There are also stories of people digging out ballast from the foreshore around where the Breach occurred, which would have contributed to the flood.

The view from Greenwich would have looked very different if the river had continued with the Breach.

in the quote from Pepys, he mentions that the Breach is now a place to lay timber, and this would have been a good place, as timber was often kept in a wet environment to stop the wood drying out and to allow gradual conditioning before sale.

In a parish map from 1703, the area is marked as a place to lay timber:

In Rocque’s map, there is an inland area of water called the Poplar Gut and in the above map it is labelled as the Breach. This was part of the area that flooded when the river breached the bank along the river.

This must have been a significant area of reasonably deep water, as on the 10th of June, 1748, it was reported that “On Saturday last, in the evening as Mr. George Newman, son of Mr. Newman, an eminent Linen Draper in Whitechapel, was washing himself in Poplar Gut, he was unfortunately drowned, although all possible means were used by a companion he was along with, to save him, to the inexpressible grief of his parents, and all who knew him”.

The Breach lasted for some years, and was still shown in the 1816 edition of Smith’s New Plan of London, which also included the recently completed West India Docks, which had been built over the Poplar Gut:

The Breach would soon be reclaimed after the publication of the above map, as the size and number of docks grew on the Isle of Dogs, and industry expanded along the edge of the river (the West India Docks and the channel across the Isle of Dogs will be the subject of future posts).

Nothing remains to be seen of the Breach today, although it was to the south of where the Canary Wharf pier is today, in the following view:

And almost as a reminder of when it was impossible to cross where the water of the Thames had breached the bank, during my visit, the path was closed, but this time for maintenance, rather than a flood:

This small area of Limehouse has changed dramatically over the last few decades, however there are still places where we can see traces of the previous industrial. docks and riverside infrastructure.

Wooden planks still poking through the foreshore, although being gradually eroded, a brick wall running along the river’s edge, and location and names of the stairs that bridge the boundary between land and the river.

You can find links to all my posts on Thames stairs in the map at this link.

You are right about the “wooden surround”. It was known as a barge shelf and did indeed provide a level surface for craft to lay on. I remember going into Limekiln Dock with a freight of something or other in the early sixties. Even then it was not used much.

Absolutely fascinating …. thank you. I love walking alongside the Thames looking for signs of the past. Your posts are so good and I’ve learnt so much! Thank you.

Another fascinating walk through the past, thank you.

Another really interesting post. I presume that the third Limehouse Hole Pier (shown in the detailed photographs) floated up and down with the tide, with the walkway suitably hinged to move with it at its outer end. I don’t know what to call that arrangement. We had one on the south side of the river to support river operations during the construction of the Thames Barrier gates and machinery in the late 1970s – the watermen called it a “Boatel”! That might be because it had a comfortable rest area on it for them to wait for call-outs to a job. They provided a taxi service to the piers, amongst other things.

Such a lot of layers of history around there. The Museum of London Docklands is well worth a visit if you are in the area: https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/museum-london-docklands It is housed in one of the two remaining former massive warehouses, which survived the Blitz. I think Limehouse was where they burned lime for the reconstruction of London after the fire of London, when building had to be made of brick, not timber.

Thank you for this and other posts. I well remember walking along the river in various areas although not as far east as this week’s post, with my then fiance who worked in the Strand for a few years after we met until we married and moved away. But also previously with my father when we had many a jaunt around various areas including limehouse and I well remember a Chinese restaurant where we dined, ironically on fish and chips in that time of my life I had never had a Chinese meal and I didn’t get one then either, I was around 13 I am now approaching my 80th rapidly. Funny what sticks in ones mind.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Quaker Burford family owned a distillery at Limehouse Hole. Wills show just how wealthy they were, with one daughter marrying a mariner involved in the slave and ivory trade. When the distillery closed is as yet unknown, but during the mid-18th century, three Burford brothers were working in or for the East India Company. Happy to share more information if of interest.

My mum lived in Limehouse/Poplar. I remember her telling me that as a child in the 30’s she would go and play there on the small beach.

A fascinating piece of research uncovering the secrets of Limehouse.

Thank you

I absolutely love your posts and have done so for a few years now. Thank you for all your work and research and I look forward to seeing more.

I have some nice memories of sitting on those steps in the sunshine, listening to the rise and fall of the water while reading Moby Dick when I first moved to Limehouse, c.2003-2004. I’ve spent a lot of time poring over old maps of that stretch of the River, but I never knew about the Breach or Gut. – Fascinating!

Have lived exactly there for the last 25 years, and find your research very insightful. Thank you, and good work.

I have only just come across your blog. I very much enjoyed this article: so well researched. Thank you very much. I look forward to reading all your previous work!

As always a brilliant piece of research

Love this post, so fascinating to know and see those markers of the old river life.

For more literary interest regarding the Limehouse Hole, it is also the setting for a significant part of Charles Dickens “Our Mutual Friend”.