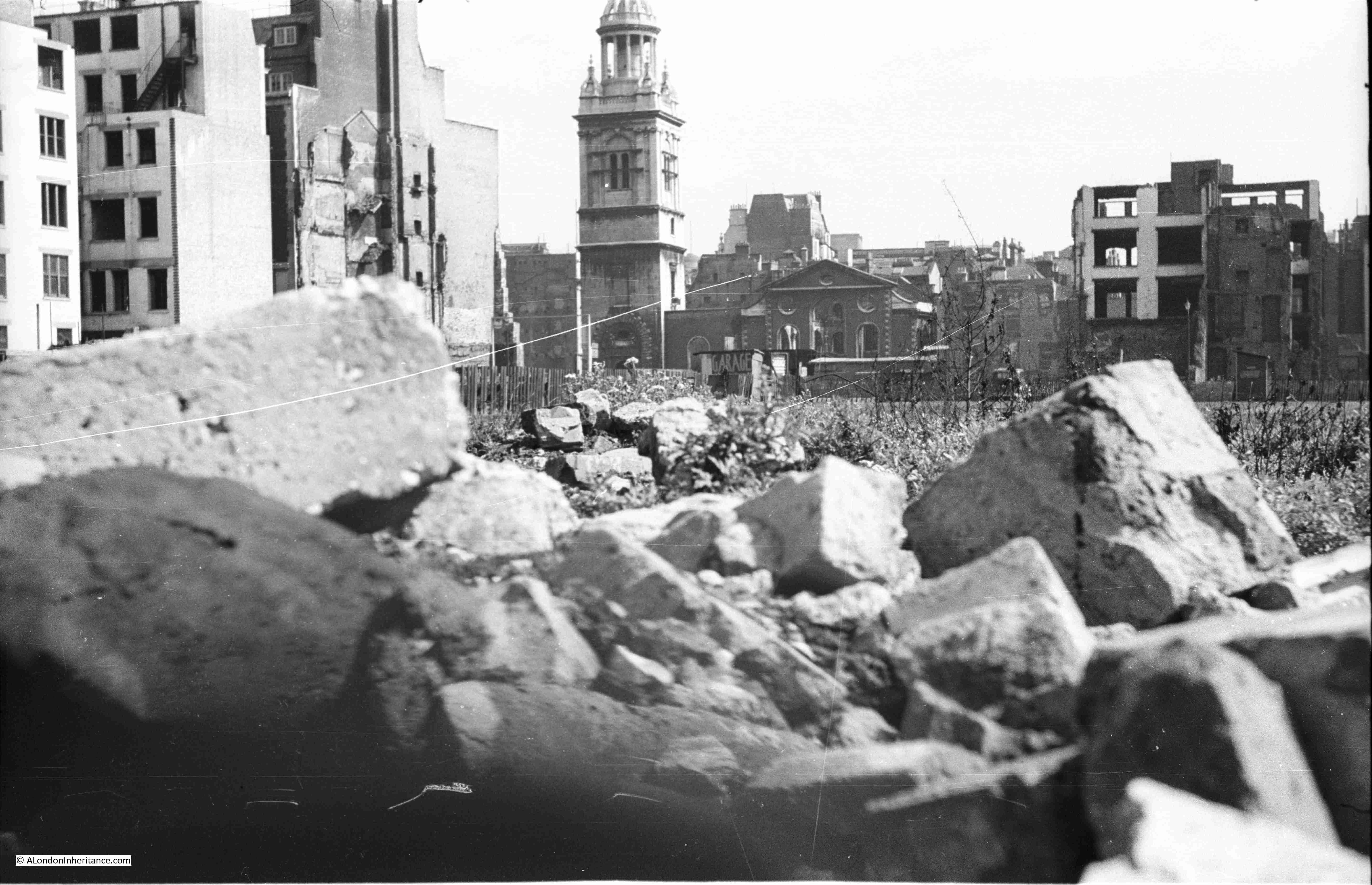

To start this week’s post, I have two photos taken by my father when he was standing where the One New Change development is located today, just to the east of St. Paul’s Cathedral:

The church in the background is St. Mary-le-Bow:

Despite the considerable building activity of recent decades, many of the City of London’s streets still have buildings dating from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, however some streets have absolutely nothing of any age, with all buildings of recent construction.

One of these is one of the streets that should have been in the two photos above, between the photographer and the church, and this street is Bread Street.

Bread Street runs south from Cheapside, just to the east of St. Paul’s Cathedral. It crossed Watling Street and Cannon Street to terminate on Queen Victoria Street,

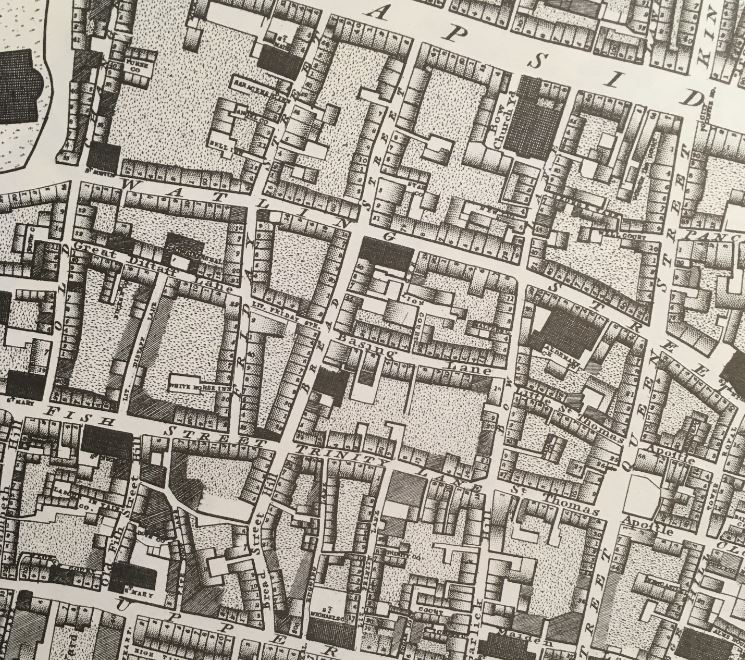

The upper section of the street is in my father’s two photos, and in the following map extract from the 1951 Ordnance Survey map, I have marked the key features which can be seen in the two photos, and are also shown on the map (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

Bread Street is to the right of the red circle, which surrounds a feature marked as a “ruin”, which the photo confirms.

A few buildings still stand around the junction of Friday Street and Cheapside, and St. Mary-le-Bow is marked as a ruin, which the photos confirm where the main body of the church can be seen as an empty shell. The tower of the church is marked by a solid square on the map, confirming that the tower is still standing and survived without significant wartime damage.

In the above map, apart from the ruin, this part of Bread Street is completely empty, as is much of the surrounding land, although as can be seen, many buildings to the right survived, including those along Bow Lane, many of which can still be seen today.

The name of the street does appear to refer to bread. Harben’s Dictionary of London quotes “So called Stow says, of bread in olde times sold for it appeareth by recordes, that in the yeare 1302, the bakers of London were bounden to sell no bread in their shops or houses, but in the market”.

This was a time when one of the main London markets operated in and around Cheapside and the surrounding streets, and there are other streets off Cheapside that still refer to the products sold, such as Milk Street and Honey Lane.

Richard Horwood’s map of 1799 provides an impression of the street at the end of the 18th century. In the following extract, Bread Street is running from the junction with Cheapside at the top of the map (just to the left of the letter P), down to Upper Thames Street, with the last section named Bread Street Hill, referring to the drop in height as the street headed down towards the Thames.

The section of Bread Street in my father’s photos is that between Cheapside and Watling Street.

The map shows that in 1799, the street was lined with individual houses, with some courts and alleys leading off from the street.

Although the area was devastated by wartime bombing, Bread Street had already suffered a number of significant changes.

Continuing south after the junction with Watling Street and in 1799 we came to a junction with Basing Lane and Little Friday Street. Both of these streets were lost when Cannon Street was extended up towards St. Paul’s Churchyard.

The construction of this major road extension in the mid-19th century, along with the construction of Queen Victoria Street, split Bread Street and separated it entirely from Bread Street Hill, which in turn cut-off Bread Street from easy street access to the Thames, and which no doubt was used to transfer the products needed for baking bread.

My father’s photos were taken from near Friday Street, which has disappeared entirely under the One New Change buildings. Bread Street survives, but the bombing shown in the two photos explains why the street is as we see it today. A street without any buildings of any age, with the majority built during the last few decades.

The view looking south along Bread Street from the junction with Cheapside:

One New Change is the large building to the right of the above photo, a building which stands over nearly all of the land seen in the foreground of my father’s photos.

Much of One New Change is a large shopping centre:

Looking south along the street:

Between Bread Street and St. Mary-le-Bow is Bow Bells House, a 215,000 square foot office building, constructed in 2007:

As Bow Bells House dates from 2007, it shows that many of these new buildings are second or third generation buildings after the devastation of war.

On the wall of Bow Bells House is a City of London blue plaque, recording that the poet and statesman John Milton was born in Bread Street in 1608:

Milton’s most well known work is the poem Paradise Lost. He was born in the street to reasonably affluent parents, his father, also John Milton and mother Sarah Jeffrey.

The street that John Milton would have known was lost during the 1666 Great Fire of London, so wartime bombing was the second time in the life of the street that it has been devastated, and put through a complete rebuild.

In the following photo, I have reached the junction with Watling Street:

Looking along Watling Street towards St. Paul’s Cathedral:

Watling Street is perfect example of why some city streets look as they do. In the above photo, I am looking along the final length of Watling Street as it approaches St. Paul’s Cathedral, and as with Bread Street, all the buildings are new.

However, walk a short distance east along Watling Street, and look back towards the cathedral, and this is the view:

Some new buildings, but many pre-war buildings remain, and perhaps this view hints at what Bread Street could have looked like before the war.

It is perhaps hard now to realise just how much whole areas of the City were devastated in the early 1940s, and how the buildings that once lined entire streets disappeared almost overnight.

But it does help explain why many of the City streets are as they are, with some streets lined with pre-war buildings, and others, even different lengths of the same street, consisting of entirely modern buildings.

Friday St still exists. New Change (the street) is entirely post-war: One New Change replaced an excellent post-war building for the bank of England by Victor Heal that was designed with the street. It was large but broken into sections and made with red brick (to recall what used to be there in Wren’s time) with stone detail., and there was public access through part of it. As usual, only after it was knocked down did critics say how good it was.

Couldn’t agree more. Realising what we’d lost made me look for other buildings by him. Euston House by Euston station is by him… but does not have the elegance of the Bank of England extension.

Just realised how similar (at least in my eyes) the New River Head Laboratories are on Roseberry Avenue. But not Victor Heal.

As per usual a fascinating comparison at to

what exists now and what tragically has been

lost. When looking at the 1799 map we only

get a tantalising glimpse of what the city was

like with a mere fraction of buildings still

remaining. Oh to time travel for just a day with

of course a smart phone to record it all.

My ancestor Joseph Lee lived in ‘Mr Brent’s house in Starr Court’ off Bread Street in the 1740s. I was sad to discover that all trace of it must have been wiped off the map 200 years later.

When watching the Lavender Hill Mob a few years ago, I saw a church tower in the shots around Queen Victoria Street – but I couldn’t work it out for a while. Turns out it’s the blitzed remains of St Mildred’s Bread Street. I think that was filmed in 1952, but I don’t know when it was demolished. I used to go to meetings in 30 Cannon Street, a ’60s building that I think is on the site of St Mildreds.

Your wonderful investigations, detective work and love – woven around the starting point of your father’s (fabulous) pictures gives such pleasure. Thank you. I grew up on the Ampton street bomb site that your father captured prior to its regeneration into an adventure playground (where I played as a child). I wondered if your father had ever gone back to capture the metamorphosis from hole in the ground to the ‘play park’ as we called it. I’d love to see any other images. I lived on Frederick street.

ah. this won’t take pictures but you can see a view here: https://live.staticflickr.com/1589/24044209339_8d22c9e42b.jpg

some of the buildings seen in your father’s pictures but a bit earlier (1942 or 1943).

a plug for my guide to the series:

https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/175542767825?hash=item28df2a10d1:g:xyQAAOSwPHxjouV6&amdata=enc%3AAQAIAAAA4LEHYwbsf9hhfeqeZDjJzHnMXtkWMXfednZcqB4WE867ABG5TH%2BKarnRoSomqYhm4VlZ9He2vtGlM373KDwmG7ciII6PsiY66yhix8JDOCv%2B3dK920ztszpTk08C82OlBUDODdvbHiaO05lT1mzDvJCEYYkr%2FsLk4nSmsw9F7a1tUqFVIg4qgf6hpKNHhzUSQRcc8MvMl1qWHroP2dZX15O5Hr356XCC7C%2BvlOG3TLaEC4iabbK3TB6gAaI3Uutv3ZB%2FVWSBrvzwvuq4dqHJKJ%2Fn0zjB2U7JTqtcy61YfUhr%7Ctkp%3ABk9SR_LH5eCHYg

For six months, during 1963-64, I used to travel to school each weekday by Tube from Aldgate East to Highbury, via Moorgate. I can’t remember just where, but at some point in the journey the train used to pass a ragged hole, torn in the wall of the tunnel, presumably by wartime bombing, where, for an instant, the blackness was interrupted by as awful a scene of urban devastation as could be imagined. As I recall, there was nothing in this vista, hundreds of yards in extent, above three or four feet in height; two thousand years of history that had been obliterated in a flash. Now, of course, millions walk or ride under and over this area daily, many oblivious of what stood here before, and, regrettably, of how the transformation was effected. Perhaps if people were more aware the awful destruction of both buildings and human beings, we’d make more of an effort to stop it happening again. Probably not.

One of my favourite views looking up Watling street towards St Paul’s.

A Great Grandfather had a business in Bread Street, my father said that the property had a plaque outside on the wall, we presumed it was in connection with my Gt Grandfather. I see that there was/is a blue plaque in respect of John Milton, so I’m wondering whether that is the said plaque, or if there was another one, so now how do I find out?

The 1940 documentary film “London Can Take It” telescopes one afternoon, evening, night and the next morning with scenes of London life during the Blitz. Among the images of destruction is one which took the ReelStreets team and supporters many months to identify.

The only indications of its possible location anywhere within London are a gentle slope to a narrow street which makes a modest turn to the left. And two bollards which could be in a style used by the City of London.

The location was eventually identified by chance in a match to a 1940 photograph held by the London Picture Archive — LPA 35376. In a wider view than the film offers, the photograph shows the location to be Bread Street seen from Cheapside and looking towards Queen Victoria Street.

It could be said that the discovery of the location was something of an anticlimax. Why? Because aside from its name our modern Bread Street possesses no markers to its former life, even topographical ones: the downward slope of the street appears to have receded, and that modest turn to the left has been ironed out. But still, we needed to know where that street was; with this London Inheritance page we now know a lot more about it.

On Reel Streets the film’s capture of Bread Street (capture 18) can be seen here: https://www.reelstreets.com/films/london-can-take-it-aka-britain-can-take-it/