A quick advert – if you would like to explore Wapping or the Barbican, there are only a few places left on my upcoming walks:

- Wapping – A Seething Mass of Misery on the 10th of June, which can be booked here (One ticket remaining)

The Lost Streets of the Barbican on the 11th of June, which can be booked here(Sold out)

All other walks have sold out.

Walk along Holborn and one of the most impressive buildings you will see is the old head office of Prudential Assurance:

The Prudential moved into their new office in 1879, which was quite an achievement given that the company had only been founded 31 years earlier in 1848.

The building exudes Victorian commercial power and was a statement building for the company that was at the time the country’s largest assurance company.

The lower part of the building uses polished granite, with red brick and red terracotta across all upper floors. If you stare at the building long enough the use of polished granite gives the impression that there has been a large flood along Holborn, which has left a tide mark on the building after washing out the red colour from the lower floors.

The building is Grade II* listed and was designed by Alfred Waterhouse with help from his son Paul. After Prudential initially moved into the building, constriction continued as could be expected on a building of this size which extends back from Holborn for some distance. The front range facing onto Holborn was completed between 1897 and 1901.

In the centre of the façade is a tower, with a large arch leading through into inner courtyards around which are further wings of the building:

Alfred Waterhouse was born in 1830 in Liverpool. His father was involved in the cotton trade, working as a cotton broker. The family had quite an influence on the future, with one of his brothers founding an accountancy firm that would eventually become PriceWaterhouse, and a second brother, Theodore, starting a legal company that became Field Fisher Waterhouse (the company has since dropped the Waterhouse name).

After attending a Quaker school in Tottenham, Alfred Waterhouse started work in Manchester where he worked on a number of private residences and public buildings, however he first major commission came when he won a competition for the Assize Courts in Manchester in 1858.

The Assize Courts were badly damaged by wartime bombing, and were condemned by the post-war decision not to rebuild. The Gothic style of Waterhouse’s work was not in fashion with architectural styles of the 1950s and 60s.

The following photo of the Manchester Assize Courts shows what an impressive building it was, and the similarities with the Prudential Building (Attribution: Old stereoscope card, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons):

His other work in Manchester included Strangeways Prison (now just HM Prison Manchester), and Manchester Town Hall, which did survive wartime bombing of the city, and still looks glorious today. Again, the same Gothic style and parallels with the Prudential building can be seen:

Waterhouse moved his architectural practice from Manchester to London in 1865.

He lost out on a competition to design the Law Courts in the Strand, but did win the competition for the Natural History Museum in Kensington, which again follows a similar style to his previous works, although with the museum, at the centre of the wide façade is the main entrance, which has two smaller towers on either side of the central block.

The Natural History Museum also displays a move from Gothic to Romanesque as an architectural style.

The design of the new building was considered such a success by Prudential that they commissioned Alfred Waterhouse and his son Paul to design a further 21 office buildings for the company in cities across the country. Some of these, such as in Southampton, can still be seen.

Waterhouse died in 1905, just a few years after Queen Victoria, and his Gothic designs with large buildings often including central towers have come to be symbolic of a style of Victorian architecture, that ended at the very start of the 20th century.

The Prudential adopted the figure of Prudence in 1848 as the symbol for the company. Prudence was said to have the qualities of memory, intelligence and foresight, enabling a prudent act to consider the past, present and future.

The figure of Prudence can be seen in a niche above the main entrance into the building and was the work of the sculptor Frederick William Pomeroy:

The Prudential Mutual Assurance Investment and Loan Association was founded in 1848 in Hatton Garden, and their target market was the sale of life assurance and the provision of loans to the emerging Victorian middle and industrious classes.

The company advertised the sale of shares in January 1849 to raise capital, and their advert gives an idea of the financial products that were starting to become widely available in the middle of the 19th century:

“The following important new features and advantages in Life Assurance, now introduced by this Association, are earnestly impressed on the attention of the public, particularly of the industrial classes, viz :-

- To enable members subscribing for £20 shares, payable by small monthly or quarterly instalments, to securely invest their savings and participate in the whole amount of profits, or in the case of death their representatives to receive the amount of each share in cash.

- To enable Members to purchase real or other property, by advances from the Association on such property.

- To grant members loans on real or other security.

- To create by periodical subscriptions an Accumulating Fund, the profits arising from which to be from time to time divided amongst its members.

- To afford an opportunity to a borrower of securing his surety from future payments in case of his (the borrower’s) death.

- Life Assurance in a reduced scale for the whole life or term of years, on lives, joint lives, or on survivorship.”

The comment “payable by small monthly or quarterly instalments” is reminder of the method used by the company to collect payments, with the “Man from the Pru” becoming the term for an insurance salesman who calls door to door to collect regular payment for Prudential’s products.

The Man from the Pru was also the title of a 1990 film which was based on the true story of a Prudential employee who was convicted of the murder of his wife.

He was found guilty and sentenced to death, however employees of the Prudential raised several hundred pounds and the case went to appeal and he was found not guilty, mainly due to very flimsy evidence being presented.

Immediatly after being acqutted, he continued his employment with the Prudential.

The “Man from the Pru” operated across the country, and was supported by company offices in multiple towns and cities.

There is a frieze along the façade of the Prudential building, which includes coats of arms of many of the places where the company had an office:

I have been able to identify a few of these arms. In the above photo, the arms of Belfast is at the left, then could be Norwich, although the castle should be above the lion, on the right is Bristol.

In the photo below, Leeds is second from left, then Coventry:

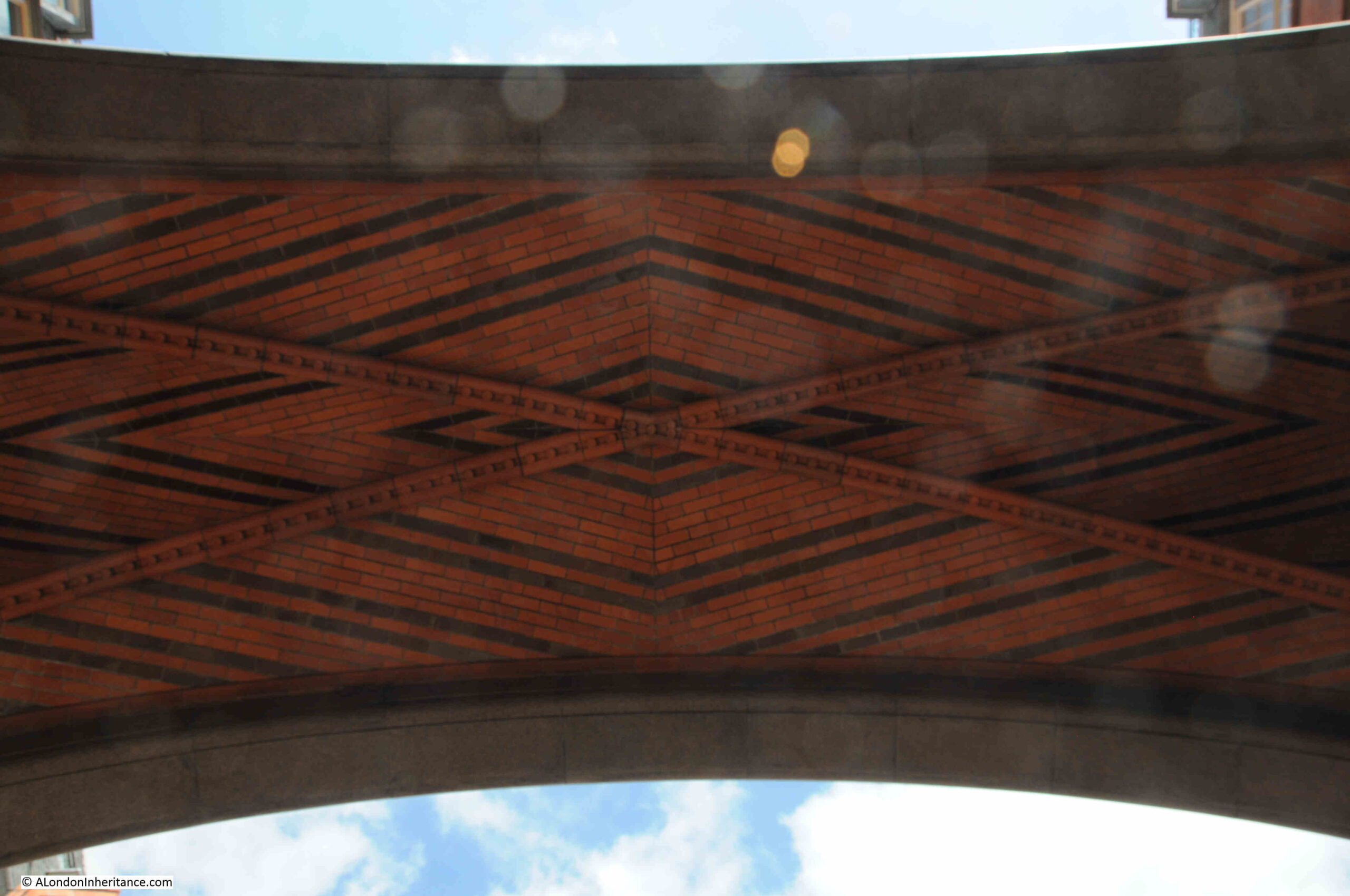

Look up when walking in through the main entrance, and admire the incredible brickwork:

When built, the Prudential building was very advanced for its time. There was hot and cold running water, electric lighting, and to speed the delivery of paperwork across the site, a pnematic tube system was installed, where documents were put into canisters, which were then blown through the tube system to their destination.

Ladies were provided with their own restaurant and library, and had a separate entrance, and were also allowed to leave 15 minutes early to “avoid consorting with men”.

The façade onto Holborn is just part of the Prudential complex as it extends some considerable way back from the street. The size of the building was not just because of the number of workers, but was also to enable storage of the sheer volume of paperwork resulting from insuring almost one third of the UK population at the peek of the Prudential’s size.

Walking through the main entrance and there is a small open space, where we can see a connecting bridge between wings of the complex, with ornate windows above a large arch:

There is a plaque on the wall, recording that Charles Dickens lived here. He lived here between 1833 and 1836 when the site was occupied by Furnival’s Inn, more of which later in the post:

More stunning brickwork in the arch over the entrance to the courtyard at the back of the complex:

The overall Prudential site was expanded and remodeled during the years of their occupation.

Being an information intensive business, their building needed to adjust to changing technology, and methods of recording and storing data.

In the 1930s the interior of the original blocks were rebuilt with large open plan floors in the art deco style in order to accommodate punch card machinery.

There was another major refurbishment in the 1980s which completed by 1993, but by then the Prudential’s days in their Holborn office complex were numbered. Departments had been moving out of central London for a number of years, for example their Industrial Branch administration had moved to Reading in 1965.

In 1999, the Prudential’s Group Head Office relocated to Laurence Pountney Hill.

Since 2019, the Prudential has been focused on Asia and the Far East. The UK businesses were transferred to M&G which today is a completely separate company to the Prudential, although Prudential still retain a head office in London and are quoted on the London Stock Exchange.

The following photo shows the rear courtyard of the complex, now named Waterhouse Square after the original architect of the buildings. The dome in the centre provides natural light to the space below:

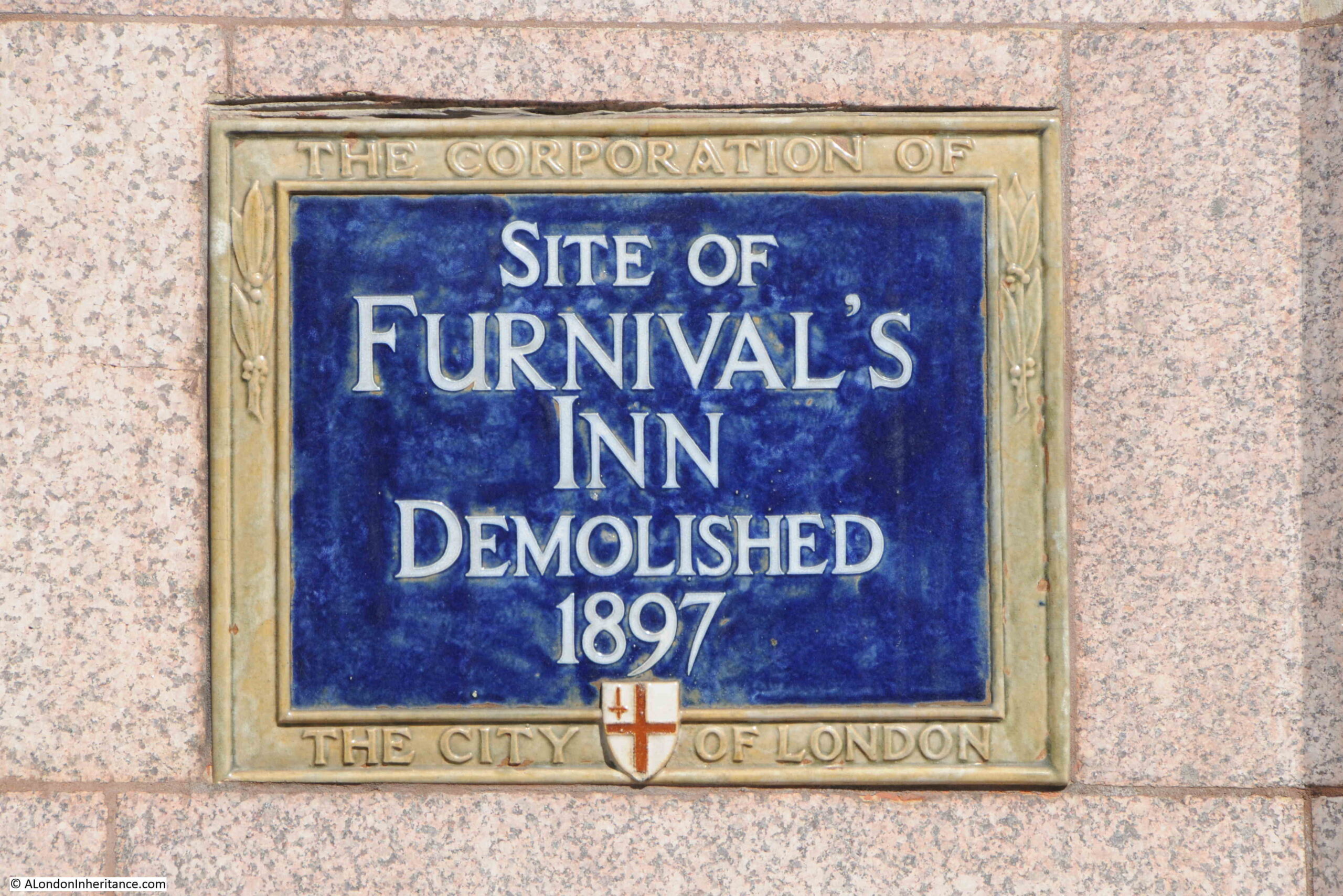

But what was on the site before the Prudential building? To discover that, we need to look at the Corporation of London blue plaque to the right of the main entrance from Holborn:

The plaque records that the Prudential building is on the site of Furnival’s Inn, which was demolished in 1897 to make way for the Prudential building.

The name comes from William de Furnival who, around the year 1388, leased part of his lands in Holborn to the Clerks of Chancery, who prepared writs for the King’s Court, assisted by apprentices who received the first stages of their legal training at the Inn.

By the 15th century, the Inns of Chancery had become a type of preparatory school for students, and by 1422, Furnival’s Inn was attached to Lincoln’s Inn, who later in 1548 took on a long term lease.

Furnival’s Inn was described as the equivalent of Eton with Lincoln’s Inn being King’s College at Cambridge. At the end of each year, Lincoln’s Inn would receive students from Furnival’s who had received their training, and reached the standard required to move up, and receive the next stage of their training, along with the greater freedoms that an Inn of Court could offer.

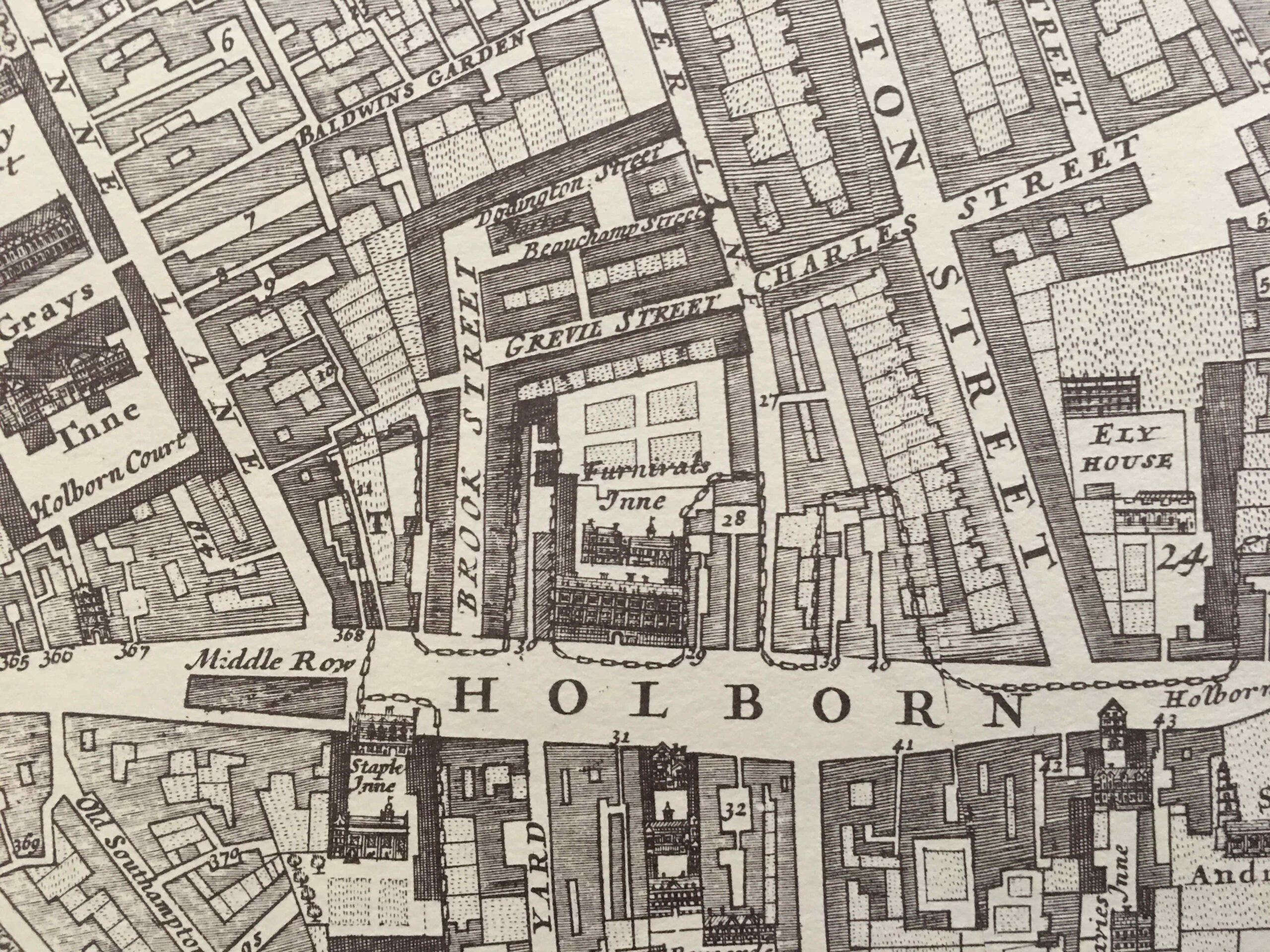

The scale of Funival’s Inn can be seen in the following extract from William Morgan’s 1682 map of London, where the inn can be seen in the centre of the map:

Furnival’s Inn occupied much of the space currently occupied by the old Prudential buiding. The map also includes some of the many legal institutions based in this part of Holborn. Part of Grays Inn can be seen to the left, and below and to the left of Furnival’s Inn is another Inn of Chancery, Staple Inn.

To the right of the map is Ely House which I wrote about in a post a couple of weeks ago.

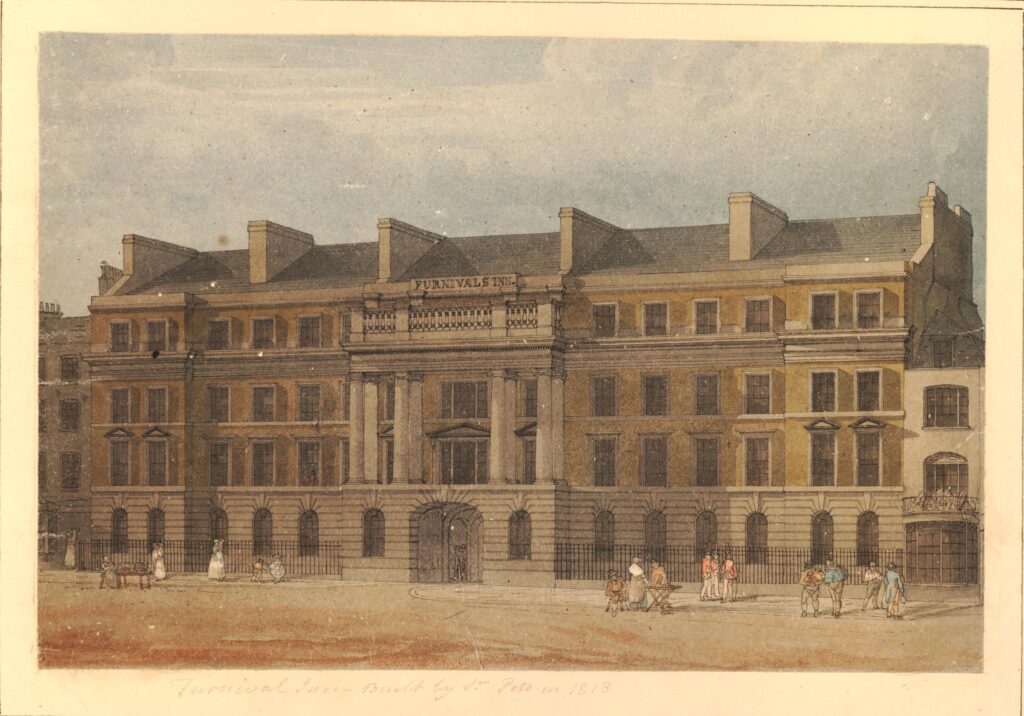

As with the Prudential building, Furnival’s Inn had a very impressive front onto Holborn. This is from the early 19th century (the following prints are © The Trustees of the British Museum):

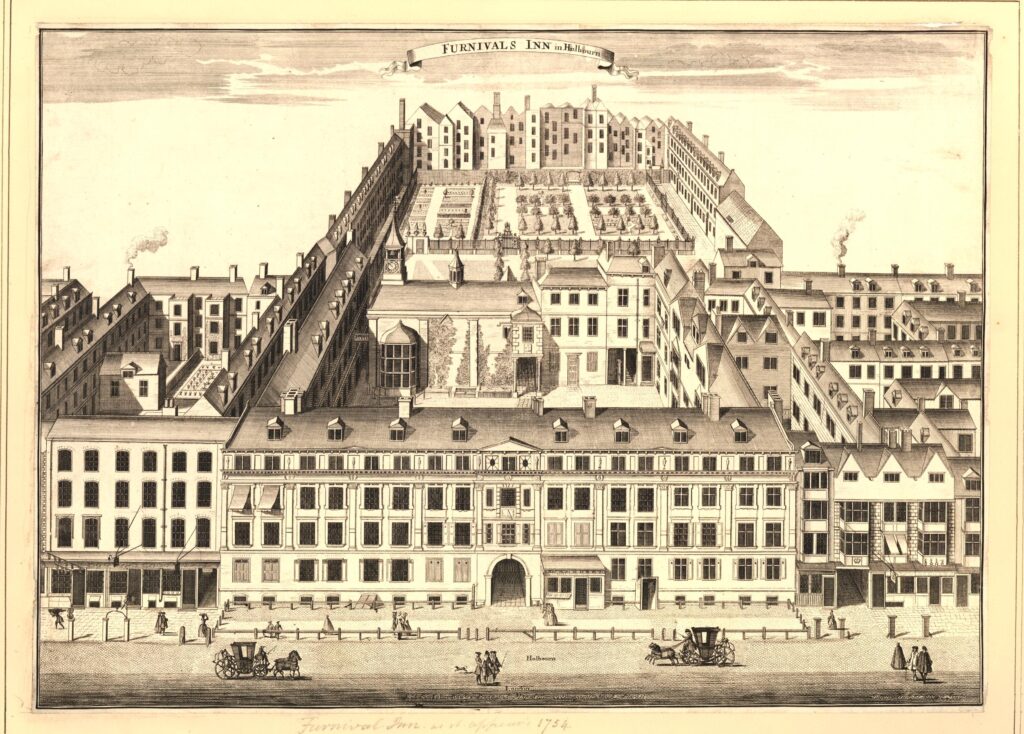

This drawing from around 1720 shows the scale of Furnival’s Inn:

As with the Prudential building, Furnival’s Inn had a central entrance from Holborn. Once through this entrance, there is an inner courtyard surrounded by buildings, and behind this courtyard is a garden, again surrounded by buildings.

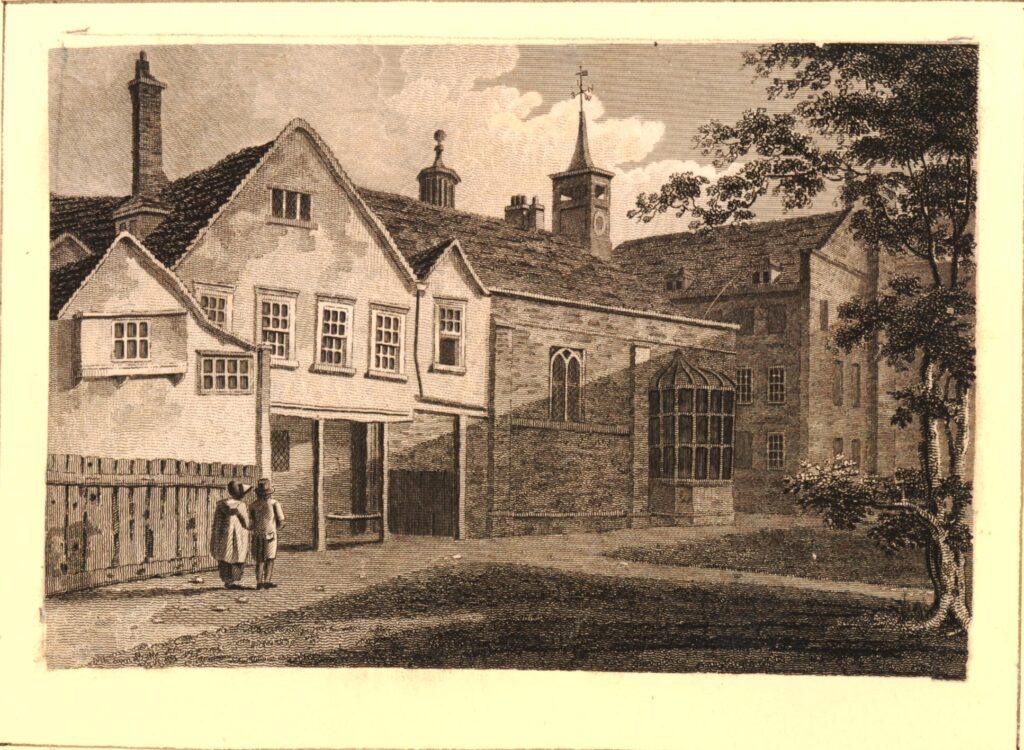

The following print is from 1804 and shows part of the inner court:

By the 17th century, the Inns of Chancery had begun to turn into societies for the legal profession, and Furnival’s Inn became residential, offices and dining clubs.

Their use as places of training and education for students before they transferred to the Inns of Court had been reducing over time and by the 19th century, Furnival’s Inn had ceased to exist for its original purpose, with only what were classed as “6 ancients and 16 juniors”.

It was dissolved in 1817, and when Lincoln’s Inn did not renew their lease a year later, some of the buildings were sold off and demolished, with apartments and a hotel occupying part of the site.

Parts of the old Furnival’s buildings were still used by those in the legal profession, and there were a number of adverts and articles in the press from solicitors based in the buildings, for example in 1880 a solicitor J.C. Asprey who had an address of 6 Furnival’s Inn was advertising for any claimants to the estate of a deceased resident of Hackney.

Final clearance of the site ready for the Prudential removed the last of the Furnival buildings and name from the site, however the Prudential building retained a similar layout with a large façade along Holborn, with inner courtyards surrounded by buildings.

Whilst the architecture and brickwork of the Prudential building is impressive, the drawings of the interior of Furnival’s Inn show a place which had evolved over time, with buildings that were probably put up at different times and for different purposes, which must have been an interesting place to explore.

The following print is dated 1820, just after the Inn had ceased to function as an inn of Chancery. On the range of buildings to the left, an open arch can be seen which leads through to Holborn, and at the far end on the right is a building which looks as if it could have been a central hall, with a large bay window looking out onto the courtyard.

After the Prudential left the building, work was done to extend at the rear and refresh / build new, along part of the western side of the building. The streets, part of which are pedestrianised, surrounding three sides of the complex are called Waterhouse Square.

The building is now used by multiple companies as office space, but I understand is still owned by the Prudential.

Fascinating to think that, whilst the buildings have changed across the centuries, this part of Holborn has been occupied by the buildings of only two institutions across almost 700 years – Furnival’s Inn and the Prudential.

A fascinating history of a well known building and the Waterhouse family. A great Sunday morning read. Thankyou.

I’d have loved to join in the Barbican walk, but I was in London on 30th April, visited the Barbican Conservatory and slipped into the end of the service at St Giles. I caught the bus from Waterloo and walked into the Barbican from the back – it was totally empty and felt like somewhere in the Soviet Union! Hope the walk goes well! Maurice.

That was a fine Sunday morning stroll. The Prudential building is a wonder but I really wish Furnival’s Inn was still there with its gardens and beautiful windows. Ah, well.

Very interesting read particularly regarding Furnivals Inn and the Hotel. I have ancestors who were residents of Woods Hotel when they got married in 1878 but I had never been able to find the exact location. Thank you I shall now be able to do more digging.

I have ancestor connections with Furnival’s Inn too. You might find interesting? https://sites.google.com/view/therobertsfamily/james-mackenzie-roberts/iii-london-1868-90

Sadly, another Waterhouse London masterpiece, St Paul’s School in Hammersmith Road — a very similar red brick and terracotta building on an equally grand scale — was demolished in the 1970s to make way for private flats and an FE college, rather than being re-purposed, as might be the case today. The only extant part of the building is the former High Master’s (later boarding) house, now the St Paul’s Hotel, but there are occasional shots of the derelict site in some early episodes of “The Sweeney”; the production company was based in the former Colet Court school building opposite (similar Victorian red brick and still standing, not designed by Waterhouse), which itself often doubled for police stations and court buildings in the series and had a standing New Scotland Yard interior set built in the former school hall.

I used to walk past this building regularly when I went to meetings nearby. Such an impressive building. I love how you can still recognise former Prudential offices in cities across the country as they have the same style. Where I live in Sheffield there’s one in the same red brick and it is now converted to flats and called ‘Waterhouse’

I’m intrigued by the meandering line on William Morgan’s map that looks like a very long chain of sausages. Is it some kind of boundary?

I’m fairly certain that this chain marks the boundary of the City of London, which includes and exclude certain plots here. Perhaps someone can explain why.

The ward of “Farringdon Without” extended up to Holborn Bars, which was roughly where the war memorial stands today in front of Staple Inn, and and the dragon boundary mark on top of what used to be the base of a gas lamp – eg https://www.vandaimages.com/1000BW0044-Staple-Inn-Holborn-London-England-late-19th.html

The buildings obstructing the road at Middle Row is the bit that intrigues me.

> The building is now used by multiple companies as office space…..

At least part of it was being used as a hotel and meeting rooms some fifteen years ago, as I attended a training course in these wonderful surroundings.

The sending of documents by tube in the then very modern Prudential building reminds me of our local very small department store in the village where I grew up in Kent that still used this method to send your cash to the cashier and the change and receipt back, in the late 1950`s early 60`s. !

That wasn’t in Erith, by any chance?

I had just been reading about inns of court and chancery, after a tour of Lincoln’s Inn, trying to understand the difference. Thank you for a wonderful post which has helped. Your blog is amazing. I hope to do one of your tours next time I’m over.

Great post, thanks. My father worked for the rival Pearl Assurance Co. He worked in Woolwich and Bexleyheath but always loved Head Office, also on Holborn, and almost as impressive, though demolished in fairly recent times. Anything on that?

The Pearl head office on Holborn is still there, although now converted to a hotel.

Good to hear that the Pearl building survives. Any chance of a post (and photos) on it?

On the list

Looking forward to that!

I can’t now keep up with London having lived there my first 50 years. I see from your photo that there is a new building on the corner of Chancery Lane where there had been an extension to the Waterhouse building by my g-g-father N S Joseph. I read somewhere that the old building had a tiled floor designed by his son Ernest, architect of Shell-Mex House, but it seem unlikely to me

Wandering lines in the boundary along Holborn is due to inns who were included in the boundary of the City of London when it was set. Area outlined north of Holborn represent different inns. They wanted to be in the city (and could vote and become members of common council) – whereas the areas that remain outside the city were individual liberties that wanted to be independent of the city for various reasons. There is a good part in the Camden History Society journal that provides more detail on this.