I will complete my tour of the City pubs in the next week, but for today’s post, I am staying in the City, and visiting the location of one of my father’s 1947 posts, which shows a view of two bombed churches.

The church tower on the left is that of St Alban, Wood Street, and the smaller tower on the right is St Mary Aldermanbury. The remains of the body of the churches can be seen at the base of the towers. The photo was taken from Gresham Street. I took a photo from the same position today, but it was totally pointless, as new buildings completely obscure the view.

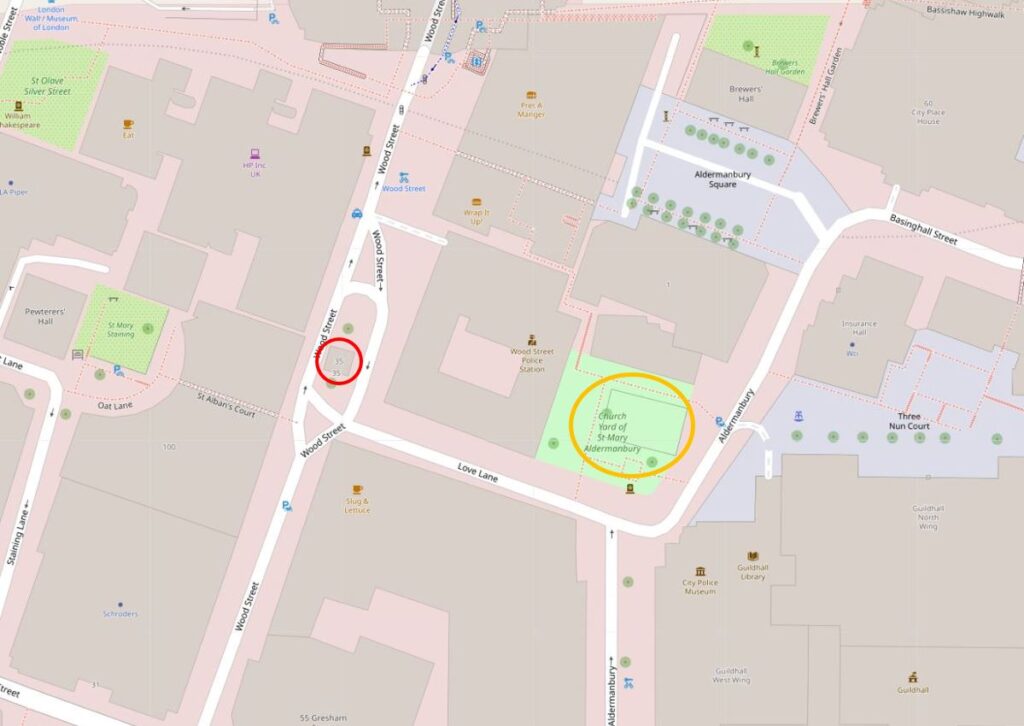

The 1947 photo shows that whilst the towers of the churches remained, the rest of the church, and the surrounding area, had been badly damaged by wartime bombing. The two churches are between Gresham Street and today’s route of London Wall. Wood Street runs between the two. The following map shows the location of the two churches today. The red circle shows the tower of St Alban, and the orange oval shows the site of St Mary (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

The 1894 Ordnance Survey map shows a very different place. The two churches, surrounded by streets, lanes, and dense building of low rise, individual buildings. The area today is occupied by large glass and steel office blocks.

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

The tower of St Alban looks out on very different surroundings today. The rest of the church was demolished in 1955 with only the tower remaining on an island, with Wood Street passing either side.

Where once the tower looked out over its surroundings, today, the surrounding office blocks close in and look down on the tower.

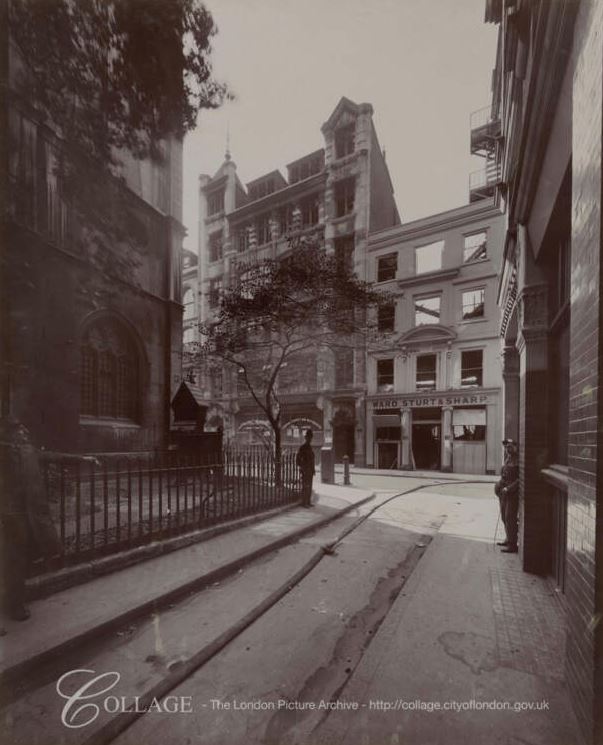

Fourteen years before the raids that would cause so much destruction, in 1926 Wood Street looked very different:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: v8482613

St Alban, Wood Street was an unusual church in that the tower was on the corner of the church. In the above photo you can see the body of the church on the right.

The church takes its name from St Alban, the first British Saint. The cathedral city of St Alban’s in Hertfordshire also takes it name from the same saint.

The London Encyclopedia states that the church was “built on the alleged site of the palace chapel of King Offa, the 8th century ruler of Mercia. In penance for his part in the murder of Alban, the first English martyr. Offa founded St Albans Abbey; and in 793 gave the patronage of Wood Street to the abbey”. There is an immediate problem with this statement as Alban was recorded being executed in the early 4th century, whilst Offa was from the 8th century, so Offa could have had no part in murdering Alban.

The connection with the abbey at St Albans is probably correct. For example, in London Churches Before The Great Fire by Wilberforce Jenkins (1917), he states “The church was, at all events, built in Norman times, for we are told that the Abbey of S. Alban owned several churches in the Eleventh Century dedicated to S. Alban; and this was one of them”.

Jenkins aligns the church with a different Saxon King “Wood Street is said to have been formerly King Adel Street, justifying a tradition connecting the church with the Saxon King Adelstane. Anthony Munday, writing in 1633, gives his personal impression of the building as it then stood:

Another character of the antiquity of it is to be seen in the manner of the turning of the arches in the windowes and heads of the Pillars. A third note appears on the Romane bricks here and there inlayed among the stones of the building. King Adelstane the Saxon, as tradition says, had his house at the east end of this church”.

A Dictionary of London (Henry Harben, 1918) adds a further twist to the street, with a first mention of the name Wodestrata dating to 1156-7. The book also includes a suggestion that the name came from the fact that wood was sold here – which is a possibility given the names of streets such as Milk Street and Honey Street to the south.

So there may have been some connection between the site and a Saxon King, the name comes from St Alban, and the abbey in the city of the same name owned the land, and the street is probably named after the sale of wood in the surroundings of the street – but as always, there is no firm written evidence from the time so impossible to be sure.

The original Norman church was rebuilt in 1633 and 1634 as the original Norman church was in a dreadful state of decay such that many of the parishioners would refuse to go into the church.

The church was then destroyed in the Great Fire, and the church destroyed in 1940 was built by Wren between 1682 and 1685 with the tower being added 12 years later.

St Alban, Wood Street in 1837:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PZ_CT_01_3672

Today, the tower sits on an island, with Wood Street passing either side. To the east of the tower is the City of London Police Station in Wood Street. In the following photo, the body of the church would be coming out from the church where the tree is located today, with the front of the church extending to the traffic island.

The church then extended back to cover a small part of the police station and the adjacent street.

I often wonder what someone who knew the area in the time of the 1926 photo would think if they could visit the area today.

The following photo is from the north, looking south down Wood Street. If you return to the 1894 OS map, you will see Liitle Love Lane, ran from Wood Street, this side of the church and circles around the church to Love Lane. Little Love Lane would have run roughly from the southern end of the traffic island, to the left, through the Police Station and round to Love Lane.

The following photo dates from 1915, and was taken from within Little Love Lane, with St Alban on the left, looking up to Wood Street.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: M0060679CL

In the above photo, the building opposite the end of Little Love Lane, showing just as a facade was the result of a First World War bombing raid on London by the Zeppelin L.13 over the 8th and 9th of September 1915. The use of incendiaries by the Zeppelin caused some serious fires in Wood Street and significant damage. A foretaste of what would come to the area in 25 years time.

The interior of the church showing the damage caused by the raids of 1940. we can see the entrance to Wood Street on the left with the large window above. The tower is on the right. As the tower now sites on an island, the eastern branch of Wood Street now runs in front of the tower in the photo below.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: M0017321CL

The second church in my father’s 1947 photo is that of St Mary Aldermanbury, of which there is even less remaining (in London) than there is of St Alban.

In the following photo I am standing at the junction of Love Lane (to the left) and Aldermanbury (to the right), looking over the site of St Mary Aldermanbury. The Wood Street police station is to the left, and the tower of St Alban can just be seen above the left hand corner of the police station.

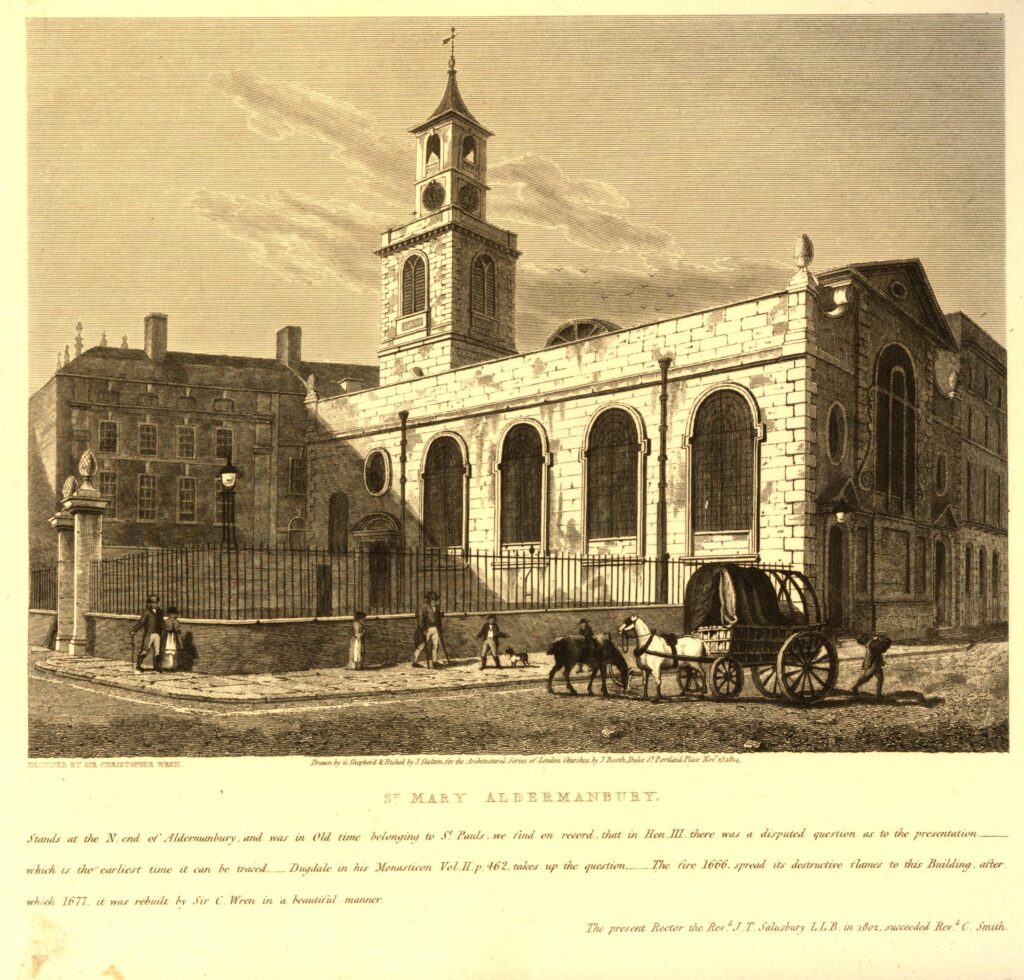

Had I been standing in the same position, just over two hundred years ago in 1814, this would have been the view:

The buildings at the left end of the church are where the police station stands today.

St Mary Aldermanbury is another medieval church, with references to it belonging to St Paul’s and / or The Elsing Priory. It grew during the medieval period, for example the Mayor of the City in 1429 and 1437, Sir William Englefield, added a steeple to the church and renewed the church bells.

The church was one of the many destroyed during the Great Fire. Rebuilt by Wren, it was this church that is shown in the above print, and that was destroyed in 1940.

The main entrance to the church, shown on the right in the above print, faced onto Aldermanbury. A first reference to the name “Aldresmanesberi” dates from 1130.

Stow suggested that the Guildhall was originally a little further west, and was on the eastern edge of Aldermanbury, and that the street took its name from being adjacent to, or having within its precincts, the ‘bury’ or ‘court’ of the alderman of the City.

The fires of 1940 destroyed the core of the church, leaving only the tower and stone outer walls of the church remaining, and it was removed in the 1960s, however the outline of the church and churchyard remains today.

The following photo is looking from Aldermanbury at what was the front of the church:

Inside the footprint of the church, looking up towards the location of the tower, with stones and bushes marking the locations of the outer walls.

What was the base of the tower, with a plaque which provides some information as to the fate of the church, which I will come on to soon.

Looking back along the church from the location of the tower.

The name Love Lane survives in the street to the south of the church, and in the surrounding buildings:

There are many stories associated with St Mary Aldermanbury. Foundlings in the parish were christened Aldermanbury, but the name Berry was used as a more day to day abbreviation. One of the murderers of the young princes in the Tower is alleged to have died at the church, after taking sanctuary.

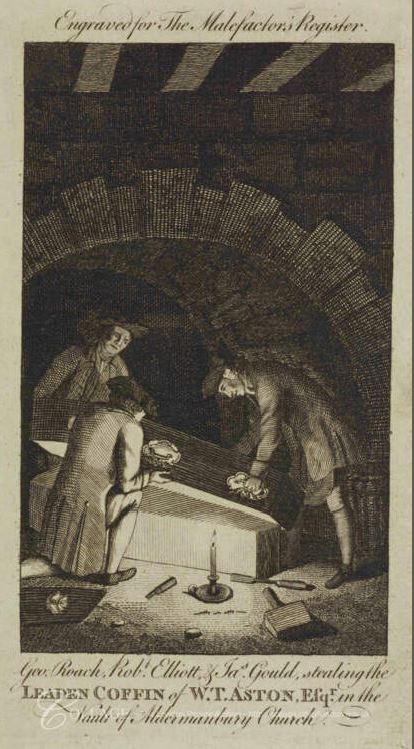

Judge Jeffries, the Hanging Judge was buried here in 1689, and the following print portrayed another event in the crypt of the church in 1778:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: q8018643

The text with the print states that George Roach, Robert Elliot and James Gould are stealing the leaden coffin of W.T. Aston in the vault of Aldermanbury Church.

The three were carpenters working on the church. At the time, coffins placed in the crypt had to be within a lead outer coffin. Overnight, the carpenters removed the inner coffin, cut up the lead outer coffin, removed it from the church, and sold the lead. They would have got away with the crime, but were reported by an apprentice who worked for their employer.

Roach and Elliot were sentenced to three years of hard labour. Gould seems not to have been charged, possibly because he gave evidence against the other two.

Sunday services were used as a means of making proclamations to the parish as a Sunday service would be the time when the majority of people in a parish were at one place, for example, in January 1754 “Sunday Morning, after Divine Service, a Proclamation for the Appearance of Elizabeth Canning, together with a Warrant direct to the Sheriffs of London for apprehending her, was read at the Door of the Parish-Church of St Mary in Aldermanbury”.

So why does nothing remain of St Mary Aldermanbury today, apart from the footprint of the church on the ground? The answer is that it was sent to America.

The Daily Herald on the 29th January 1963 provides some background:

“The cost of removing the Wren church of St Mary Aldermanbury to America was revealed yesterday. A staggering £1,670,000.

The church, which now stands in the shadow of the Guildhall, is being shipped stone by stone to Westminster College, in Fulton, Missouri, where it will be reassembled.

it was bombed into a shell in the war and is a gift from London to the Americans.

Professor of Architecture at Nebraska University and Dr Robert Davidson, of Fulton, are in London to look into the arrangements for the church’s removal.

‘Virtually a military operation’ was how they described the task to me. But they seem to think it worthwhile. Just as well that their universities are a lot better off than ours.

The church is being re-erected at Fulton as a tribute to Sir Winston Churchill. At Fulton in 1946, Churchill made an historic speech about the need for western unity. In it he used a phrase that was to ring around the world – the Iron Curtain”.

In America, a large model of what the relocated and repaired church would look like, was made, and the importance of the project was such that President Truman made an inspection of the model.

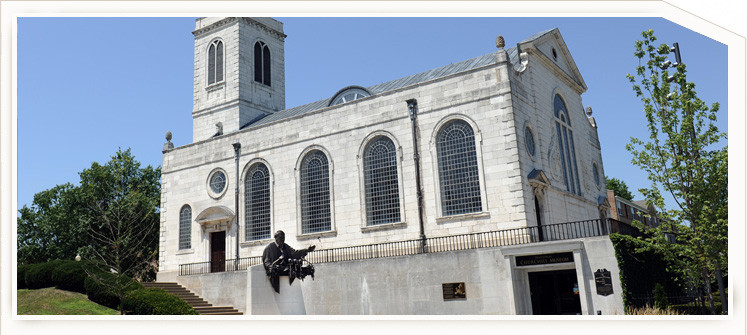

The church is now part of the National Churchill Museum. The museum’s website has some video of the church in its new location.

I wonder what Wren, and the many thousands of parishioners who used the church over the centuries, would have thought of the new location?

Love Lane still runs to the south of the churchyard of St Mary Aldermanbury:

The churchyard includes a bust of Shakespeare. The playwright does not have a direct connection with the church, however two parishioners who were also buried in the church played a key part in ensuring Shakespeare’s plays would be available for future generations.

John Heminge and Henry Condell, were “Fellow actors and personal friends of Shakespeare. They lived many years in this Parish and are buried here. To their disinterested affection the world owes all that is called Shakespeare. They alone collected the dramatic writings regardless of pecuniary cost”.

Heminge and Condell published the Shakespeare Folio of 1623 which collected together his plays, many of which have no other printed copies.

The folio is represented by the open book below the bust. On the right page is printed the following words from Heminge and Condell “We have but collected them, and done an office to the dead, without ambition either of selfe profit or fame, onely to keepe the memory of so worthy a Friend and Fellow alive as was our Shakespeare”.

As usual, there is so much history to be found in a small area of the City. A plaque on the edge of the churchyard records the location of the Aldermanbury Conduit which provided free water from 1471 to the 18th century (the first date is strangely specific).

A rather nice drinking fountain, the gift of a Deputy of the Ward to the Parish of St Mary Aldermanbury sits at on the corner of the churchyard:

City churches fascinate me as they are a fixed point in an ever changing City. Performing the same function since medieval times, possibly earlier, and the surroundings of these two churches has changed so dramatically over the last 70 years.

Two bombed churches, they are now only ghostly outlines of the original churches. With St Alban only the tower remains, and with St Mary, only the foot print of the church and churchyard, but at least they remain.

Strange though that the stones of the tower of St Mary in my father’s 1947 photo are now standing in a location, many thousands of miles away.

It is also strange how stories spread about a location. Whilst I was taking photographs of the tower of St Alban, there was a couple looking quite intently at the tower. The man asked me if this is where people were hanged. I answered that I am sure it was not such a location – to which he replied very firmly that he was sure that it was. I have not heard or read any stories about executions taking place around St Alban.

In researching these posts, I always try to read and compare multiple sources, but as time stretches back, legends, hearsay and stories become accepted as fact, so it is always best to question and check – which is part of the enjoyment of discovering London.

The St Mary story is fascinating, and the site today perhaps the City’s nicest garden.

What an excellent article. Absolutely fascinating. Your research is impressive.

Poor old Lindon. Gone forever

Another great piece- particularly interesting to see the pictures showing how the tower related to the church building in Wood street. And soon the Police station is to become a hotel….

Thanks for clearing up some points that had perplexed me, namely the orientation of St Alban and the layout of the original street. That Collage photo makes sense of it all now. Because I live in Yorkshire, most of my visits to the City are usually a case of me hurrying through on foot from one terminus to another but I did make time last year to visit St Alban, following a post you did on the old Roman fort. And stopped briefly to enjoy the lovely garden that remains in the footprint of St Mary Aldermanbury. I sometimes wonder what it must have been like, the day before the planes came, to walk in that part of London, now lost forever. An excellent post to enjoy over the first coffee of the day.

The Virgin of Aldermanbury (1958) by Madeleine (‘Mrs Robert’) Henrey is a fascinating tour of the City churches in this area and in some cases, like St Lawrence Jewry, their reconstruction. The title refers to a statue of the Virgin that used to stand in an alcove above the porch but which was probably looted during the Blitz. Madeline worked as a PA in a soft goods firm in Aldermanbury in the 1920s and goes back to visit the range of buildings running south of the Chartered Insurance Institute just before they were demolished.

There are still a few copies of her book knocking around on Abebooks for not very much.

Mrs Henrey’s books are fascinating social historical documents. Surprisingly, after the war she and her husband lived in America.

I put this up on my Facebook account in May 2012 with photos of one of Mrs Henrey’s books (https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=442417969119887&set=a.191237904237896 ):

Years ago at school I was friendly with a boy whose parents were very well-off. His mother had been a habitué of high society in the West End of London before the Second World War and at some point in her life had dated famous men including Richard Todd, the British actor who died a year or two ago. I went round their house in the holidays – by this time my friend’s mother was a middle-aged alcoholic married to an alpha male-type company director. I was a voracious reader who would read books in an afternoon at their house while she pottered about and chatted with my friend. Although she was not short of money she would not buy books – only borrow them from the library – and she often borrowed quite interesting books – I first encountered ‘Beloved Infidel’ and the writings of Scott FitzGerald at her house. She frequently had one or other of the series of books that comprise the autobiographical writings of Mrs Robert Henrey and if she left any book lying around I would read it.

Mrs Henrey was born Madeleine Gal shortly before the First World War in (I think) Normandy. She could remember, from her earliest years, retreating before the German army in 1914. In her adolescence she came to work in a hotel in London and lived in Earlham Street in Soho and she described the West End before during and after the Second World War. The pre-war world she described was the fashionable West End, and her experiences as a very immature young woman, and how she met her husband who was a journalist related to the proprietorial family on the long defunct Morning Post, married him, and became a mother in bombed-out post-war London. When I was a very young man I met c/Conservative older men who had read the Morning Post before it became absorbed by the almost equally c/Conservative Daily Telegraph in the late 1930’s. Mrs Henrey describes conversations with people in ruined places I am familiar with that have been rebuilt in the intervening decades. Her writings were fascinating to a very young man for the insight into what women were interested in and what they thought of men and what they expected from us, and from time to time I have picked up one of her books and read it, though not for a few years now.

In one of the Beaconsfield charity shops the other day I came across this book by Mrs Henrey. It cost me £1.50 ($2.25) and so I bought it. I haven’t read it yet and won’t have time for the next few months but I thought I would show you the covers. It is a first edition but I have no intention of selling it or any idea what it would fetch.

See also:

https://www.facebook.com/lawrence.linehan/posts/570866376275045

We have visited St. Mary Aldermanbury several times in Fulton, Missouri. It has a beautiful interior, and the building sits atop the Churchill Museum, which is small but actually quite good. Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech has a connection to the church I attend in St. Louis, Central Presbyterian. A building program in the 1930s, which created our current church building, was led by an elder, who unfortunately died just at the building was completed. His widow eventually decided to endow a series of lectures in his name at Westminster College in Fulton, one of which was held before World War II started. The second was Churchill’s speech.

Perfect read on a Sunday morning

Nice to see these two churches again. I worked in Wood Street telephone exchange for a while in 1963/64 and often wondered what the rest of St. Albans was like so it was interesting to see the 1926 photo. I also remember St Mary Aldermanbury as a heap of stones, all carefully numbered like a giant Airfix kit. Many thanks for your posts.

I’ve got in my collection of interesting London pictures a colour photograph of the two bombed out churches. I don’t now know where it came from – but I do know it took me a long time to work out that it was these two churches, as wherever I got it from didn’t state what the subject was exactly. Odd that it’s colour… if indeed it’s not been recoloured. It’s a Time & Life Getty Image – but I can’t find it by googling. I’l post it here… if it were possible.

It shows a gang working on clearing the rubble around the churches – so I guess it is still during the war, which makes me suspicious that the colour is not original. The photographer is standing probably on the corner of Wood Street and Love Lane, looking east towards St Mary.

Once again, your post is fascinating. I share your interest in City Churches, partly because (as you note) they bear witness to London’s past while remaining in the present. I have made a “game”, in my frequent trips to London, of trying to visit all of the surviving churches and the locations of those that are gone. I have a handful left to visit. Sadly, because I live in Chicago, I don’t expect to be able to return to London for many months. (I refuse to think of it in terms for years!). Thank you for your incredible research and photos.

Colour photography existed during the war.

That was fascinating, especially as the company I work for has its London offices in Wood Street (in 100 Wood Street which can be seen in the background of several of your photos). I was unfortunate enough to work in Canary Wharf before this so it’s a real pleasure being back in the historic heart of the City where the history has not all been bulldozed out of the way to be replaced with hideous high-rise buildings).

I really enjoyed this article, especially about St Mary Aldermanbury. Thank you.

I lived in 64 Aldermanbiry during the war so St Mary was the place next door to me. It was a bombed out building with feral cats which my mother fed. She started the garden in the City. She stayed throughout the blitz. I was at boarding school. During holidays the City was my home. I loved it and all the little roads cycling around on my own. A sweetshop in Basinghall street used to give me chocolate severely rationed.

Buildings were bombed out where the Guildhall rebuilt opposite 64.

I remember Fownes Gloves further along near Gresham street. All changed and unrecognisable now but pictures still in my head.