House of Illustration is a small arts and education charity dedicated to the art of illustration – an art form that can be found on almost every aspect of modern life. Originally based in King’s Cross, the charity is moving to a very historic location and transforming into the Quentin Blake Centre for Illustration.

Quentin Blake has been one of the most prolific and high profile illustrators of the 20th and early 21st centuries, with his work across many forms of illustration, including illustrating the works of the author Roald Dahl.

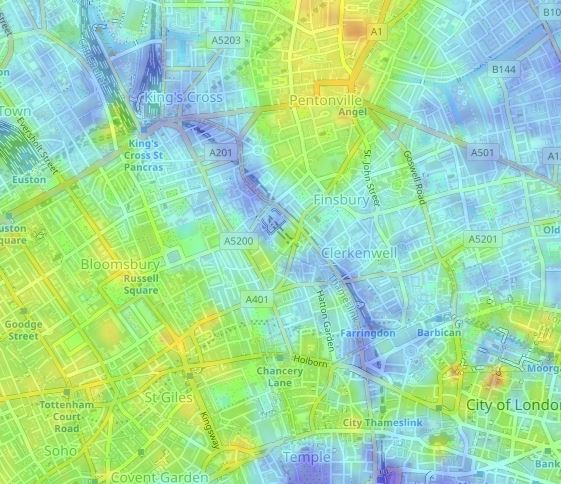

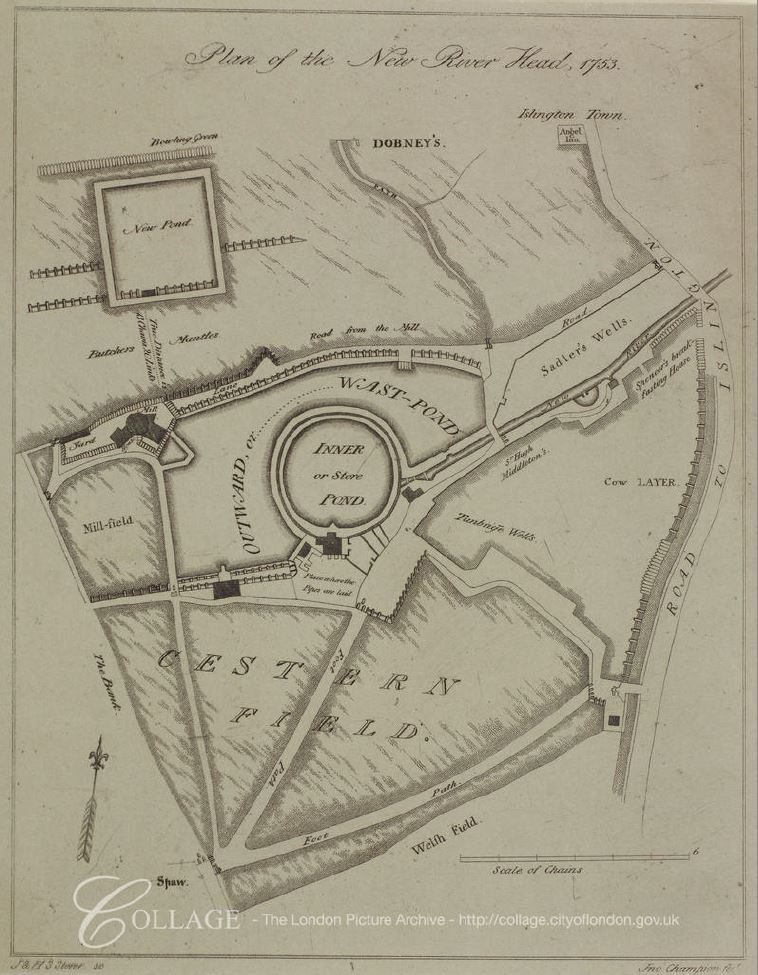

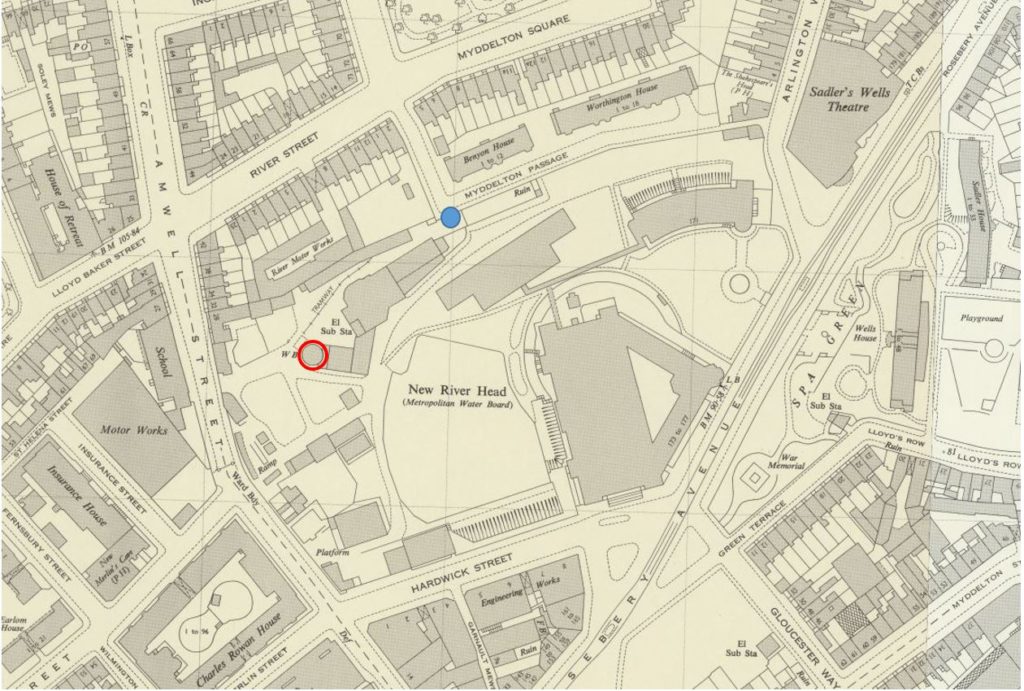

The new location for the Quentin Blake Centre for Illustration will be at New River Head in north Clerkenwell / Islington, the site of the reservoir that terminated the first man made river bringing supplies of water to the city of London in the early 17th century.

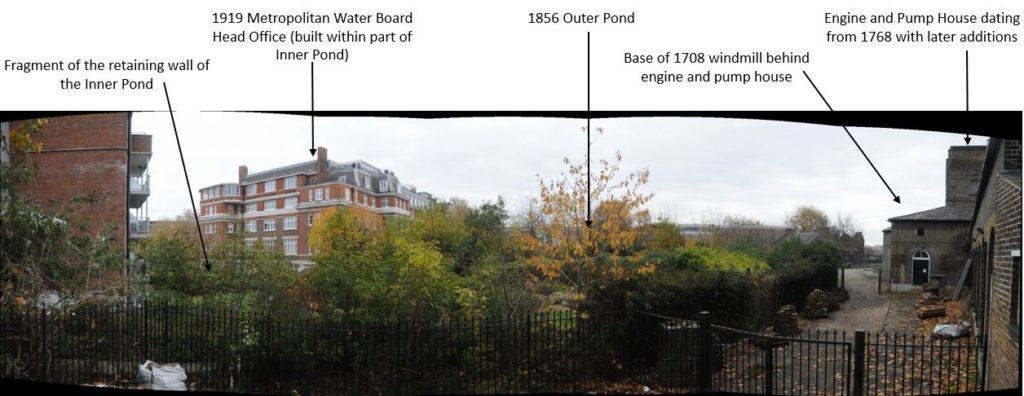

Having been empty for many years, the base of the early 18th century windmill, the engine house and coal store at New River Head will be sensitively transformed over the coming year into the new centre. This transformation will ensure that these buildings are preserved and after being hidden away for so many years, will be given a new life hosting one of London’s small, but so important charities and exhibition spaces. The centre will also eventually be the home for Quentin Blake’s archive.

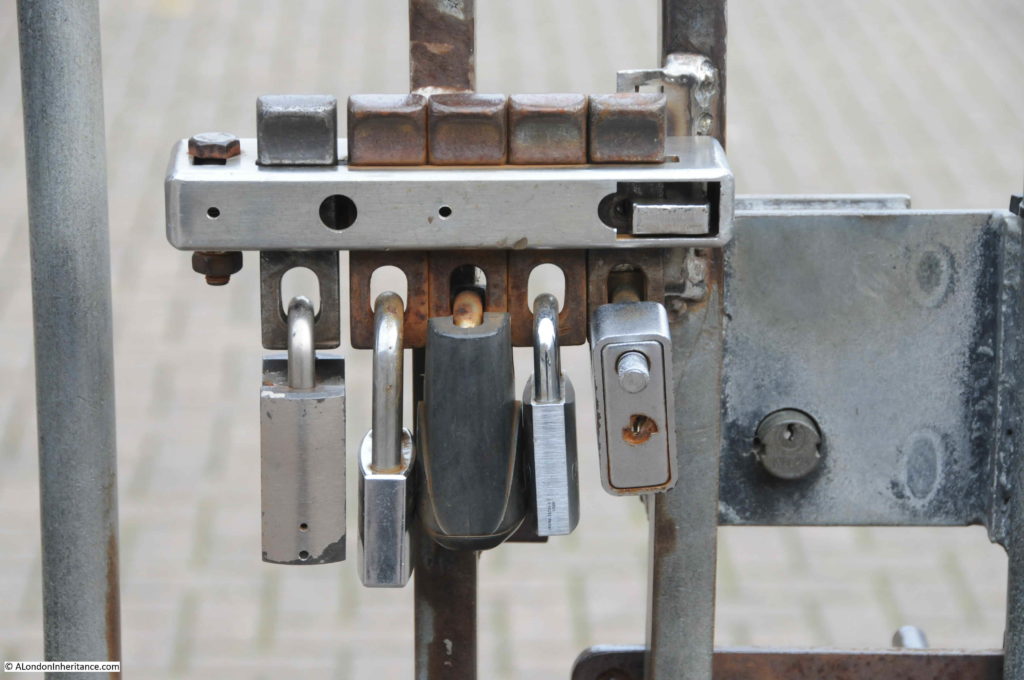

So why is this the subject of this week’s blog post? A while ago, a colleague from the Clerkenwell and Islington Guide (CIGA) Course was offered the opportunity to visit the site and create a walk that would illustrate how water has been key to the area’s development, and to visit the interior of the windmill and coal stores and the exterior of the engine house before work begins to create the new centre.

Offered the opportunity to be involved, it took about a second to say yes, and for one week only there is a series of walks exploring the Fluid History of Islington, which, with the support of the Quentin Blake Centre for Illustration, includes access to the base of the early 18th century windmill, the coal stores and around the outside of the engine house at New River Head. I will be guiding on some of these walks, and colleagues from CIGA will be guiding the rest.

This is a unique opportunity to explore how water has influenced the development of the area, see these historic buildings up close, and learn about their future use.

The full set of walks are available to book here

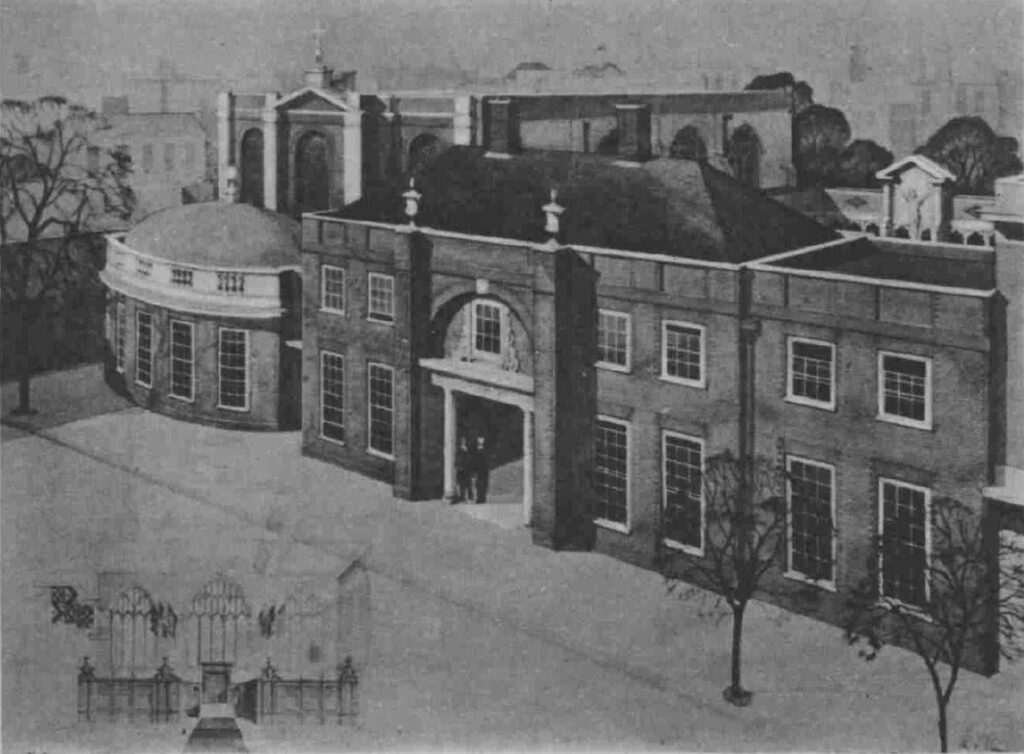

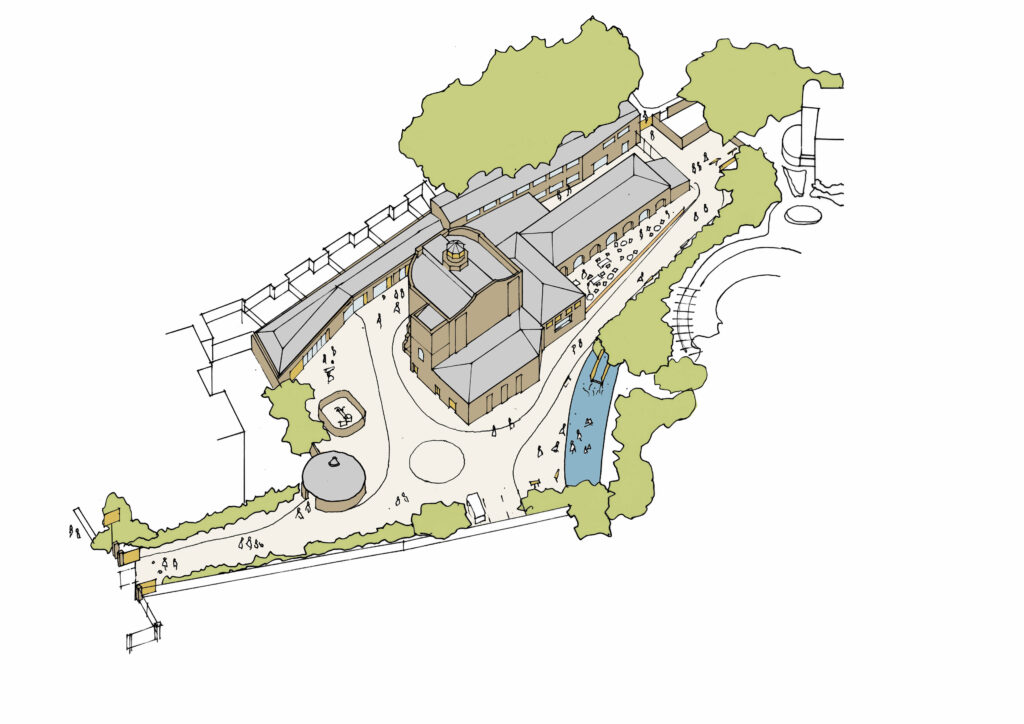

As an introduction to the walk, the following illustration is the proposed plan of the new Quentin Blake Centre for Illustration.

Credit: Quentin Blake Centre for Illustration, Tim Ronalds Architects

In the above plan, the round building to the lower left is the base of the early windmill. I took the following photo of the building on a recent visit:

The large building to the right is the old engine house. The interior will not be open for the visit as it is currently difficult to navigate, however we will walk around the outside of the building and talk about the part the engine house played in the development of New River Head and London’s water supply, along with the future of the site.

Credit: New River Head © Justin Piperger

The old coal store forms the longer building to the right, and will be open during the visit:

As can be seen from the following illustration, when transformed to a new exhibition area, the fabric of the building will retain its industrial heritage:

Credit: Quentin Blake Centre for Illustration, Tim Ronalds Architects, Prospective Gallery

The location for the new Quentin Blake Centre for Illustration is at a place that played a key part in the supply of clean water for London’s growing population for a considerable period of time.

The New River and reservoirs at New River Head were the first serious attempt at bringing significant volumes of water into London from a distance, and avoiding the need to draw water from the Thames, which by the end of the 16th century was not exactly a healthy source of drinking water.

The New River dates to the start of the 17th century, a time when there was a desperate need for supplies of clean water to a rapidly expanding city. Numerous schemes were being proposed, and the build of the New River tells the story of how the City of London, Parliament, the Crown and private enterprise all tried to gain an advantage and ownership of significant new infrastructural services, the power they would have over the city, and the expected profits.

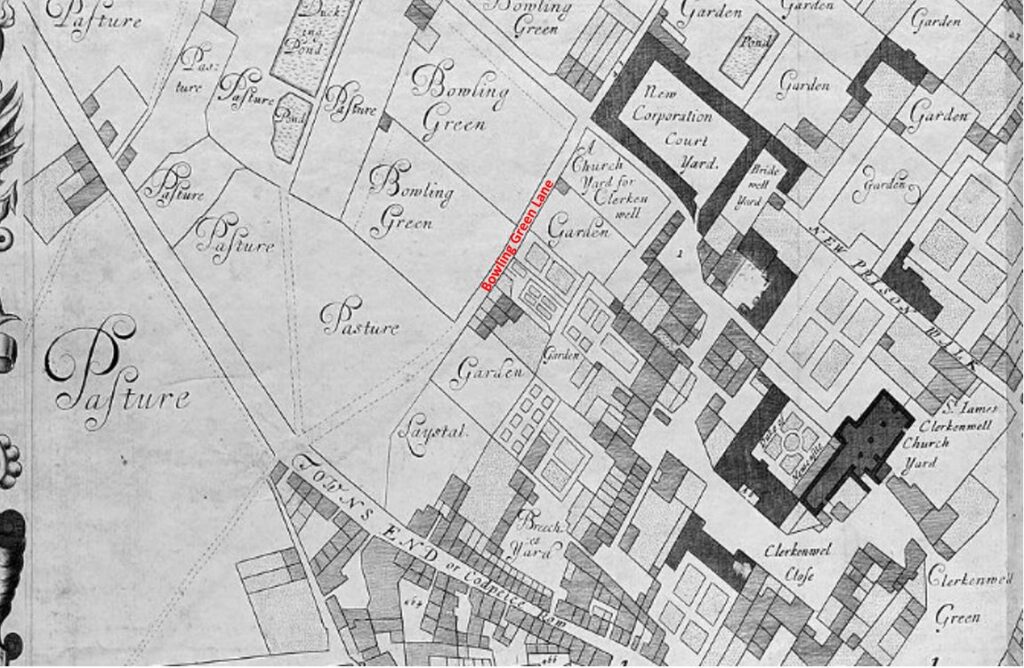

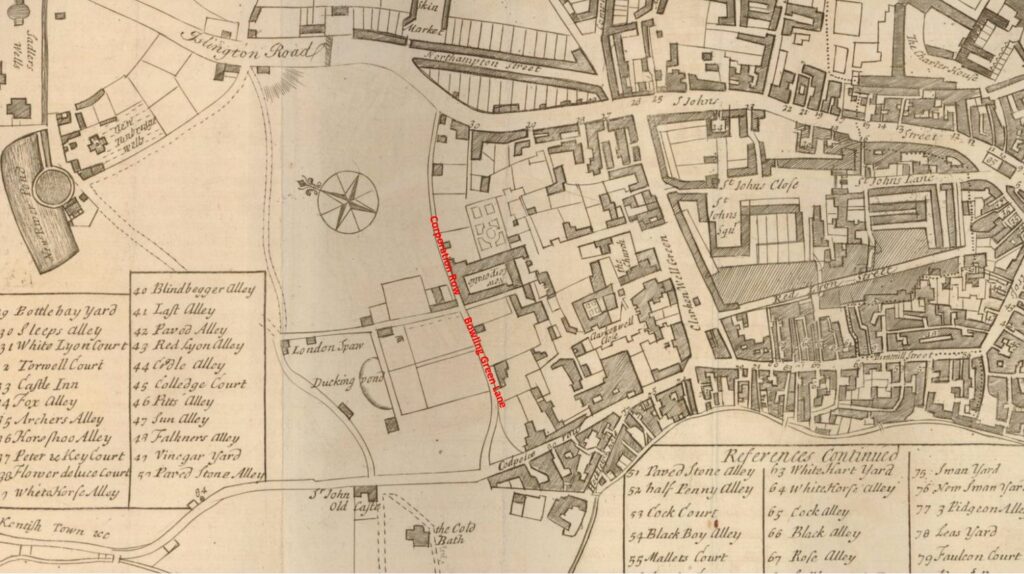

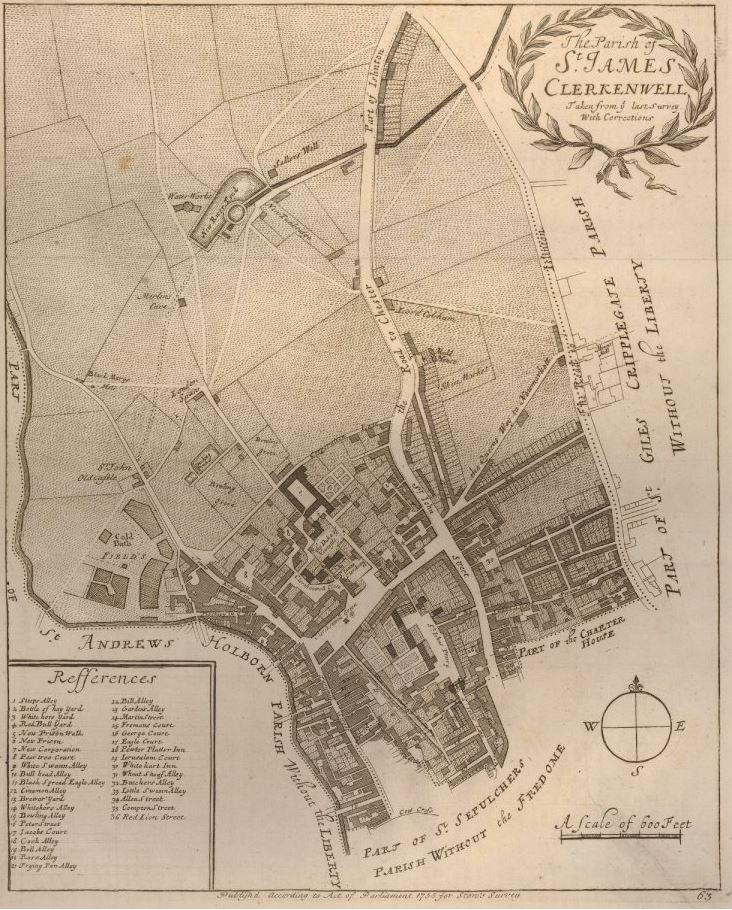

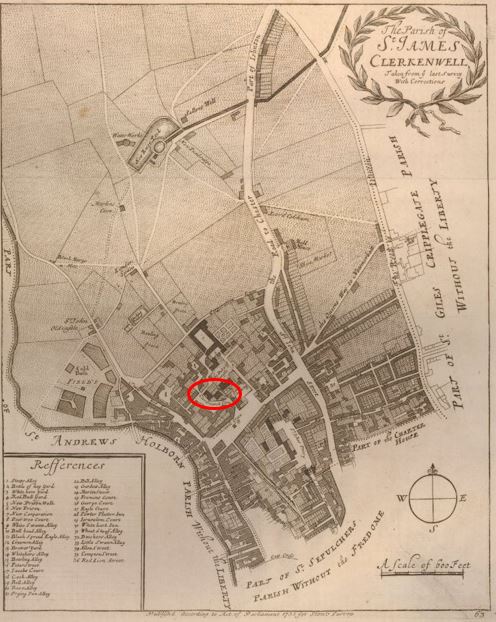

The New River proposal was for a man-made channel, bringing water in from springs around Ware in Hertfordshire (Amwell and Chadwell springs) to the city. A location was needed outside the city where water from the New River could be stored, treated and then distributed to consumers across the city.

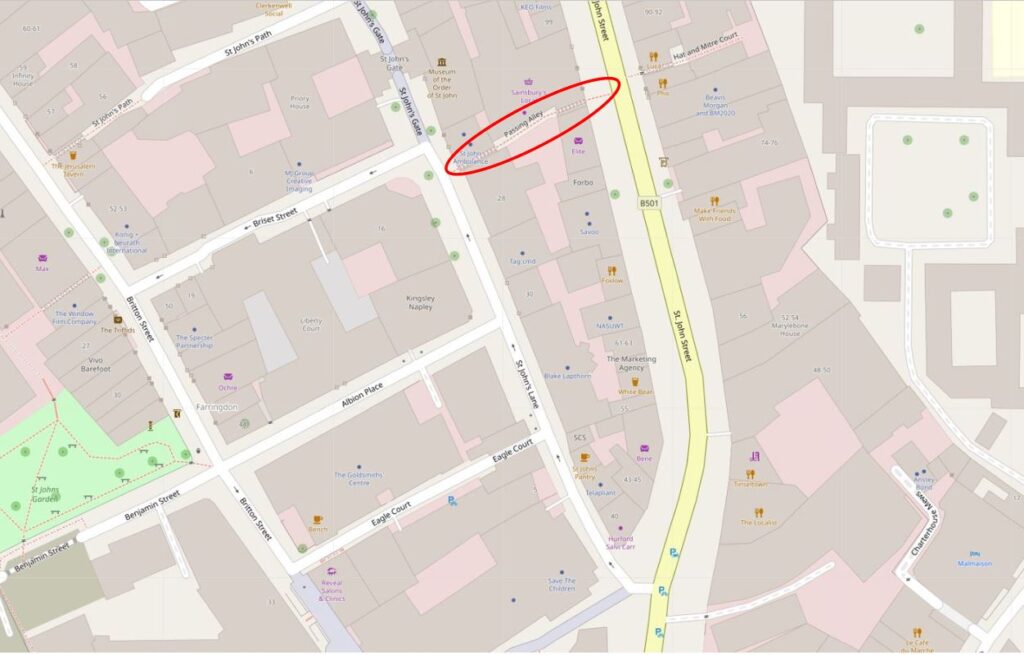

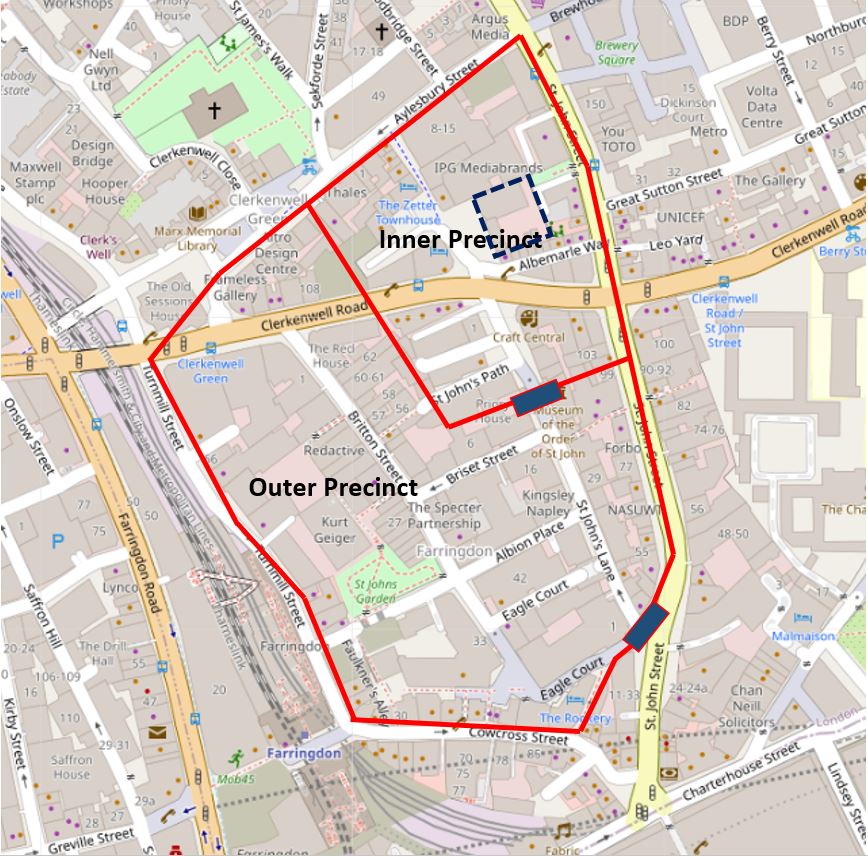

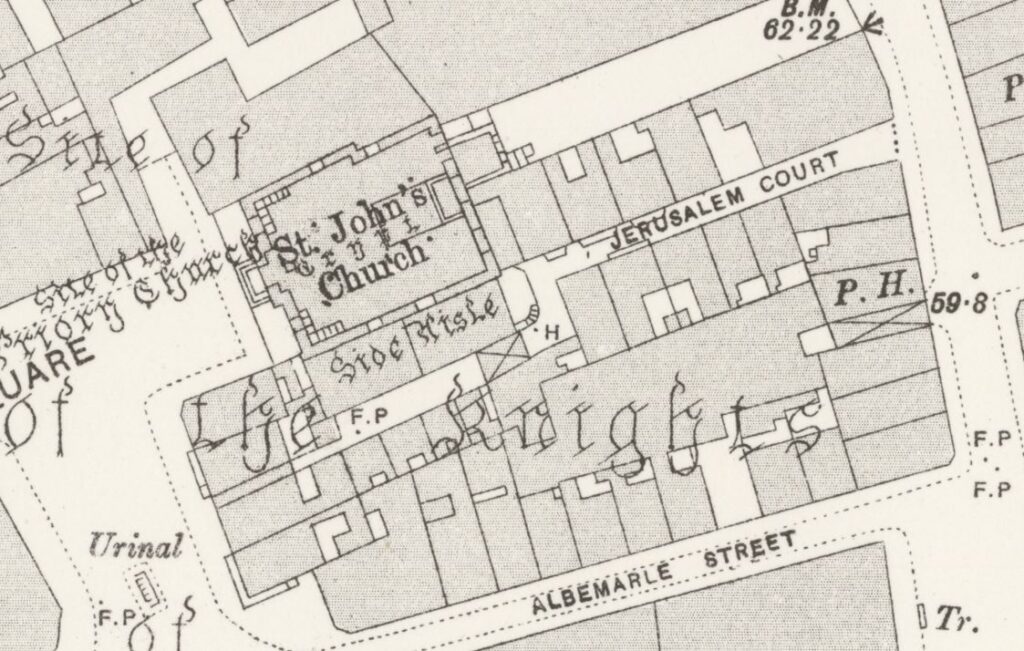

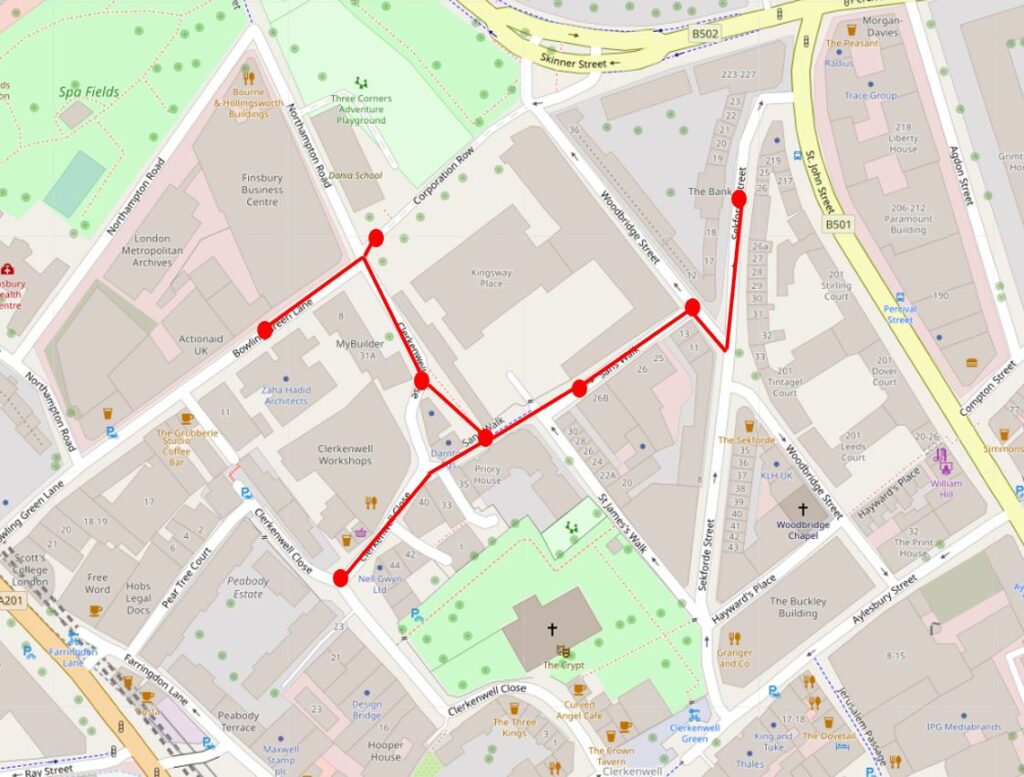

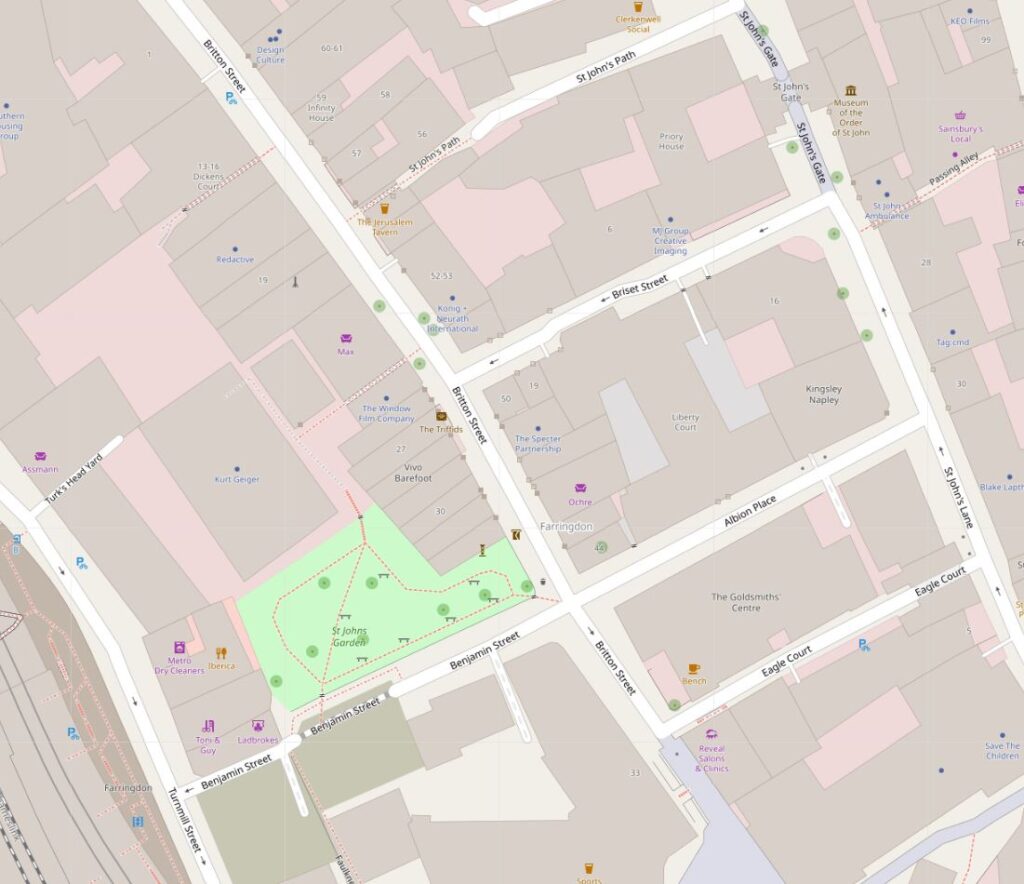

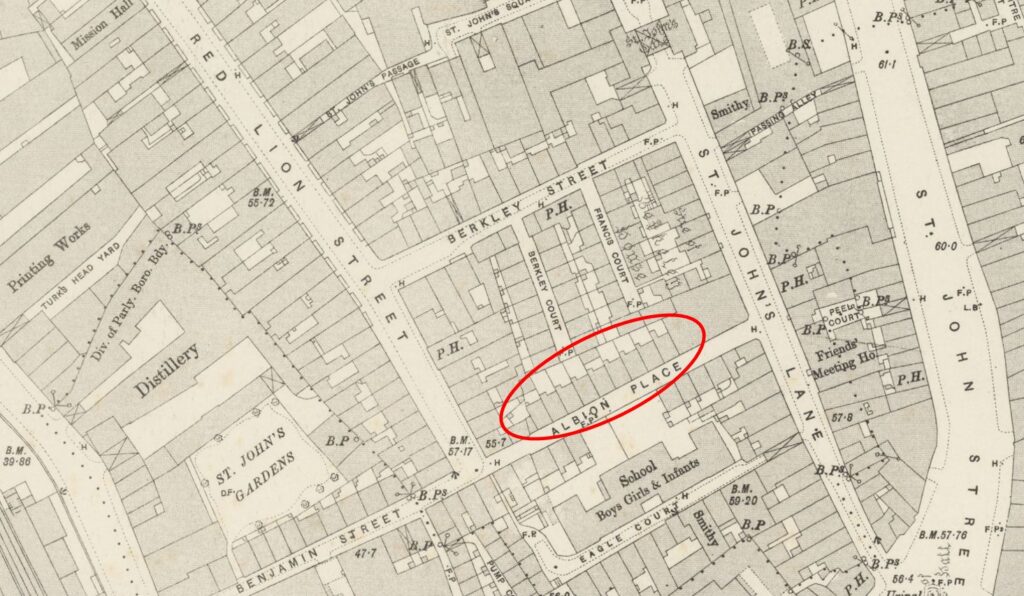

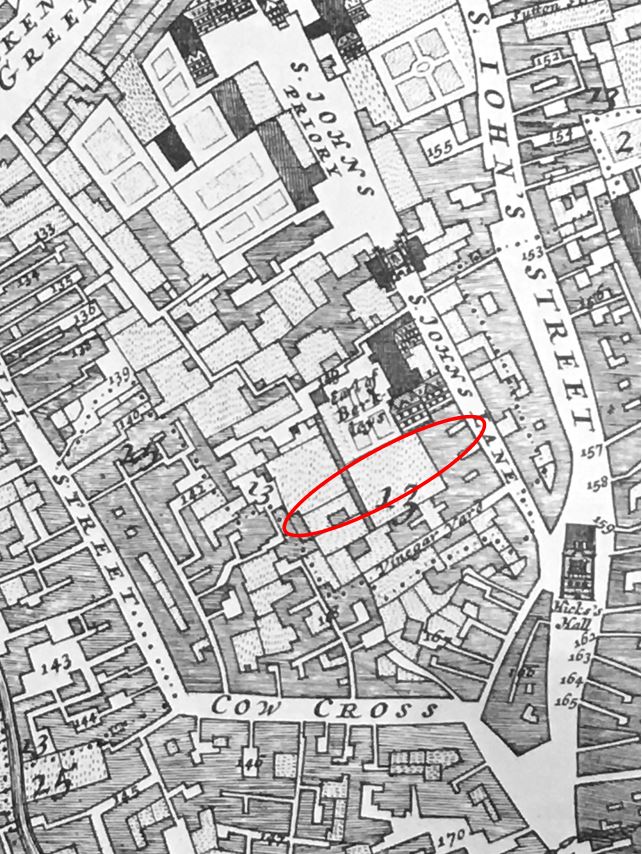

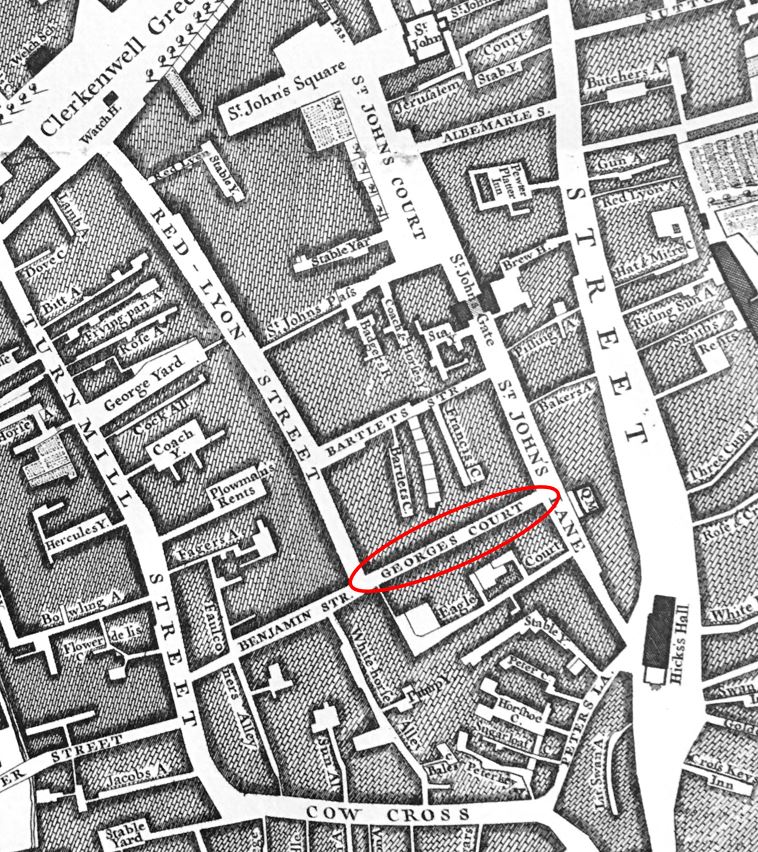

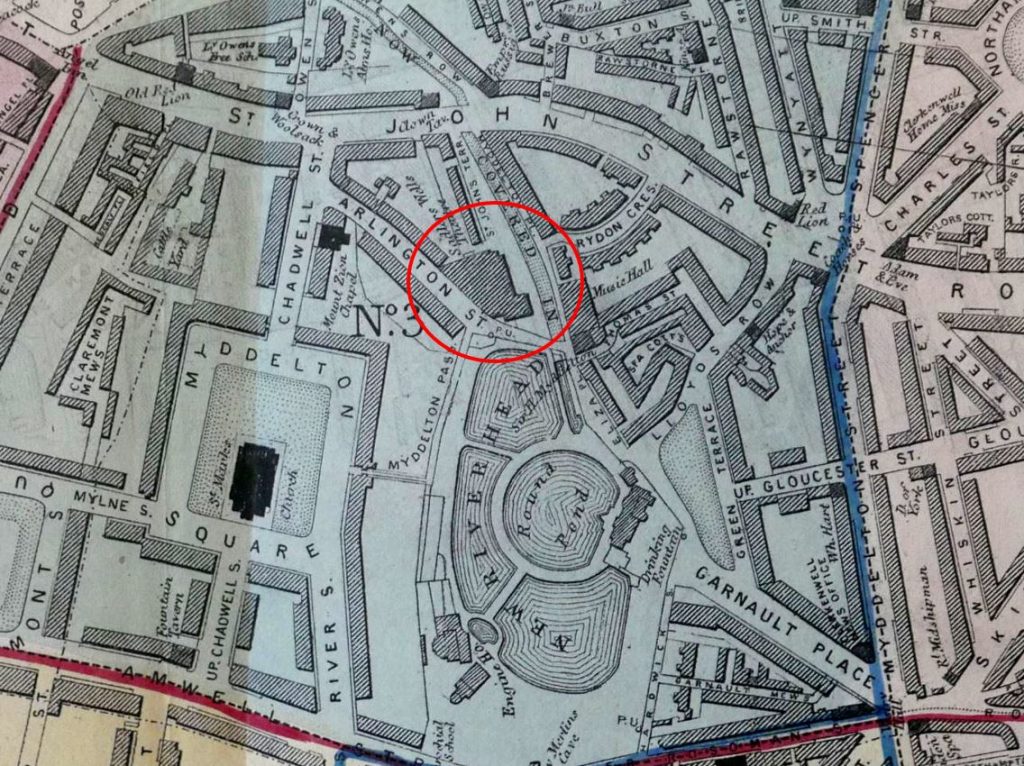

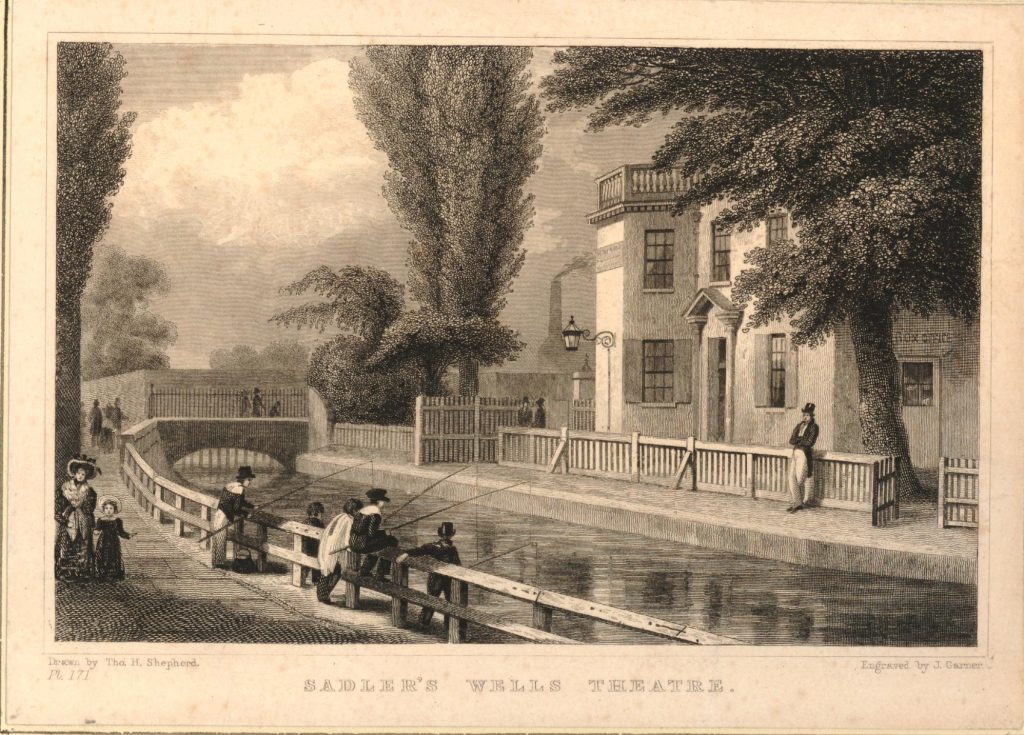

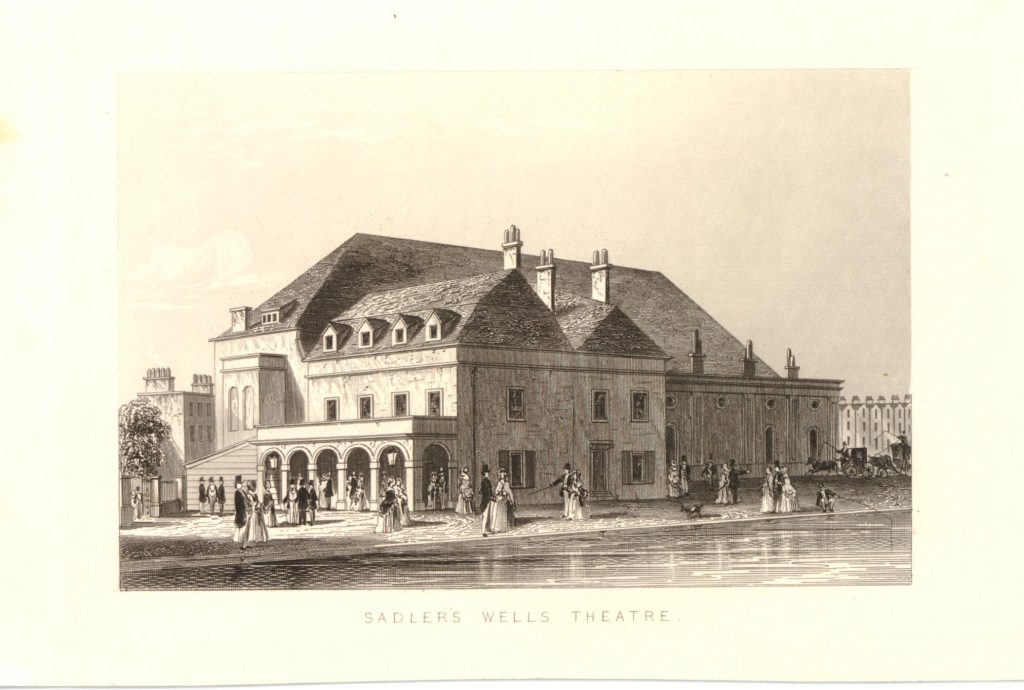

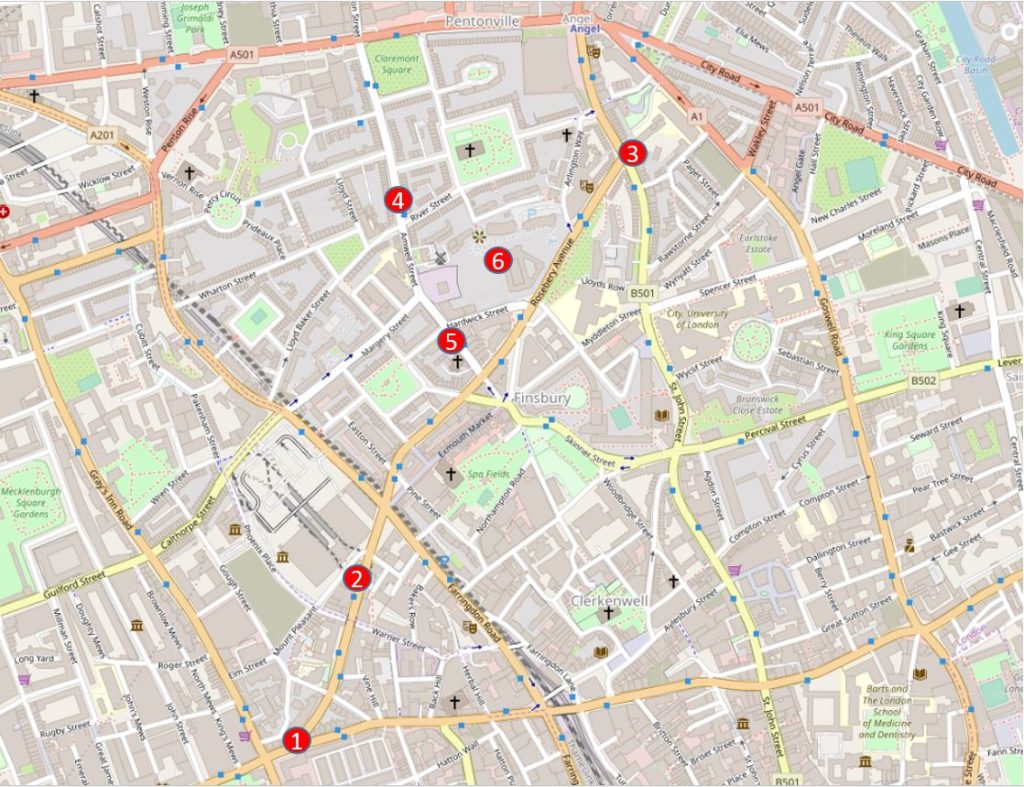

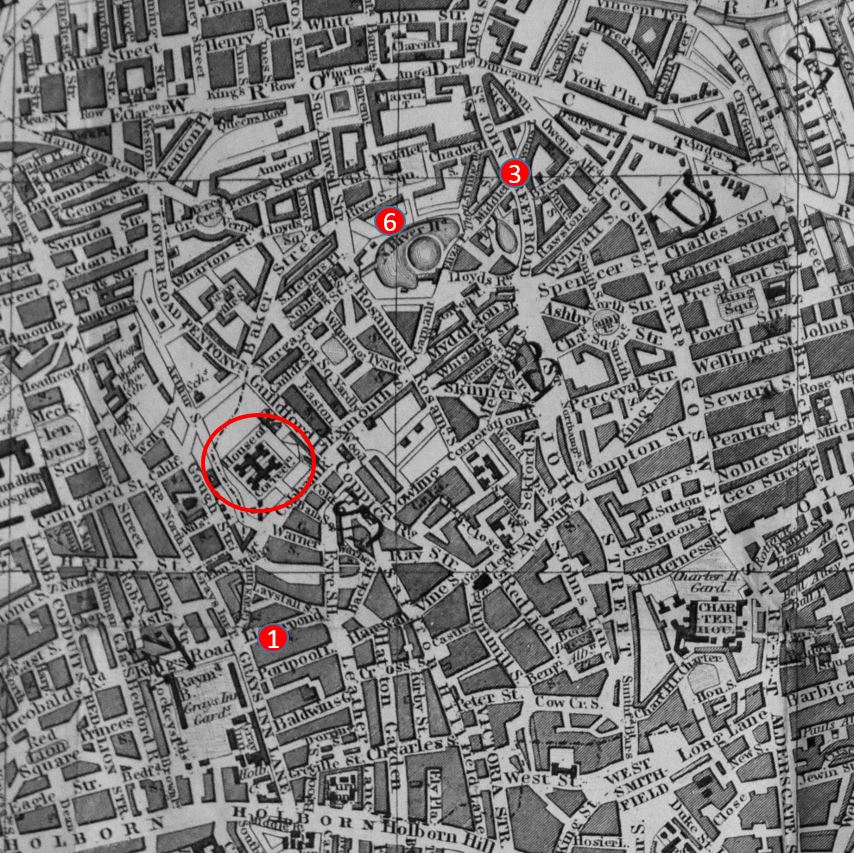

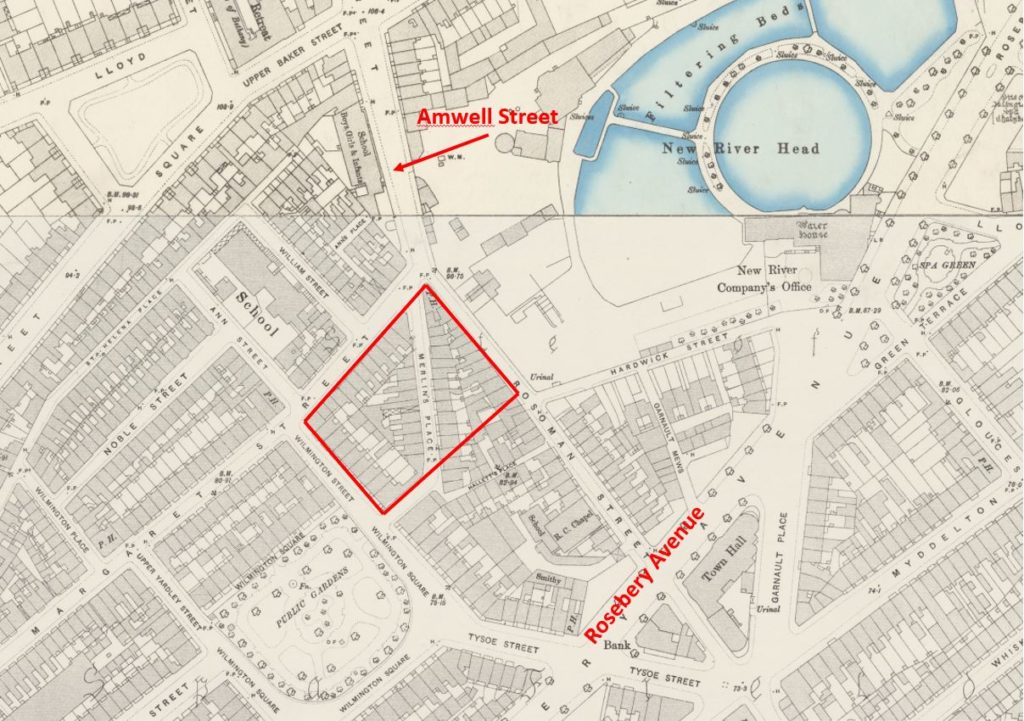

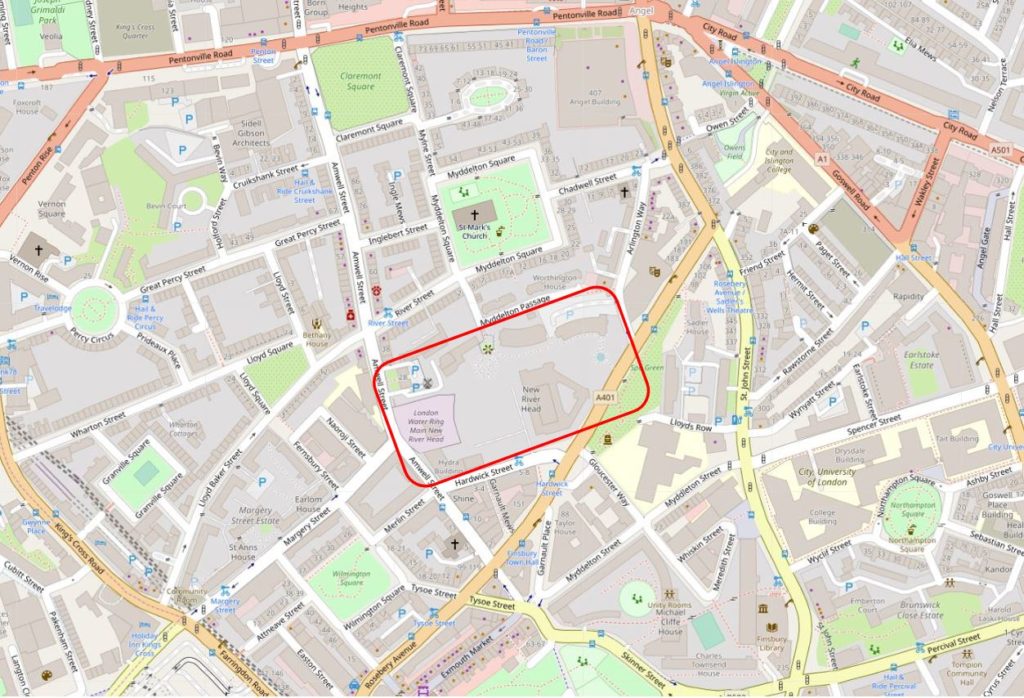

The site chosen, called New River Head, was located between what is now Rosebery Avenue and Amwell Street. The red rectangle on the following map shows the area occupied by New River Head (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

The story of the New River dates back to 1602 when a former army officer from Bath, Edmund Colthurst who had served in Ireland, proposed a scheme to bring in water from Hertfordshire springs to a site to the north of the city.

As a reward for his military service, he was granted letters patent from King James I, to construct a channel, six feet wide, to bring water from Hertfordshire to the city.

Colthurst’s was not the only scheme for supplying water to the city. There were a number of other private companies, and the City of London Corporation was looking at similar schemes to bring in water from the River Lea and Hertfordshire springs.

Whilst Colthurst’s project was underway, the City of London petitioned parliament, requesting that the City be granted the rights to the water sources and for the construction of a channel to bring the water to the city.

In 1606 the City of London was successful when parliament granted the City access rights to the Hertfordshire water, a decision which effectively destroyed Colthurst’s scheme, which collapsed after the construction of 3 miles of the river channel.

It was an interesting situation, as Colthurst had the support of the King, through the letters patent he had been granted, whilst the City of London had the support of parliament.

The City of London took a few years deciding what to do with the water rights granted by parliament, and in 1609 granted these rights to a wealthy City Goldsmith, Hugh Myddelton. He was a member of the Goldsmiths Company, an MP (for Denbigh in Wales), and one of his brothers, Thomas Myddelton was a City alderman and would later become Lord Mayor of the City of London, so Myddelton probably had all the right connections, which Colthurst lacked.

Colthurst obviously could see how he had been outflanked by the City, so agreed to join the new scheme, and was granted shares in the project. Colthurst joining the City of London’s scheme thereby uniting the rights granted by James I and parliament.

Work commenced on the New River in 1609, but swiftly ran into problems with owners of land through which the New River would pass, objecting to the work, and the loss of land. A number of land owners petitioned Parliament to repeal the original acts which had granted the rights to the City, however when James I dissolved Parliament in 1611, the scheme was given three years to complete construction and find a way to overcome land owners objections, as Parliament would not be recalled until 1614.

There were originally 36 shares in the New River Company. Myddleton had decided to enlist the support of James I to address the land owners objections, and created an additional 36 new shares and granted these to James I who would effectively own half the company.

in return, James I granted the New River Company the right to build on his land, he covered half the costs, and Royal support influenced the other land owners along the route, removing their objections, as any further attempts to hinder the work would result in the king’s “high displeasure”.

The New River was completed in 1613. It was a significant engineering achievement. Although the straight line distance between the springs around Ware and New River Head was around 20 miles, the actual route was just over 40 miles, as the route followed the 100 foot height contour to provide a smooth flow of water, resulting in only an 18 foot drop from source to end.

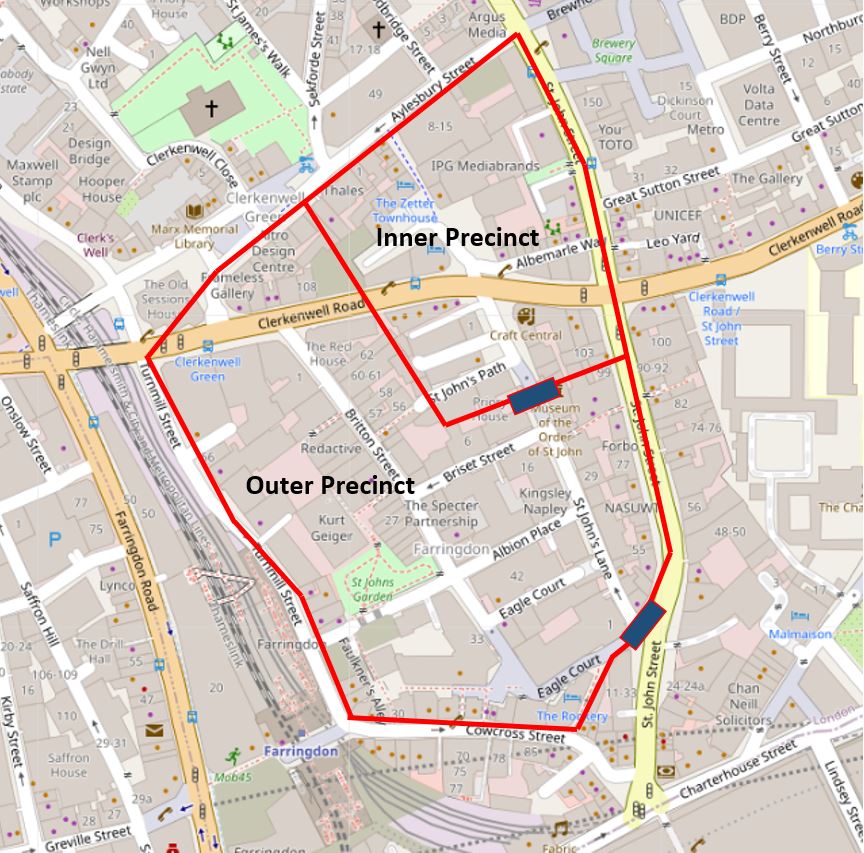

The New River Head location was chosen for a number of reasons. A location north of the city was needed to act as a holding location, from where multiple streams of water could then be distributed through pipes across the wider city.

The location sat on London Clay, rather than the free draining gravel found further south in Clerkenwell, and it was also a high point, with roughly a 31 meter drop down to the River Thames, thereby allowing gravity to transport water down towards consumers in the city.

The site already had a number of ponds, confirming the suitability of the land to hold water.

By the end of the 17th century, London had been expanding to the west and developement was taking place around the area now called Soho, including Soho Square.

The challenge the New Rver Company had with supplying water to London’s expanding population was down to having sufficient volumes of water available, and with maintaining water pressure.

The City of London was much lower than New River Head, and water pressure was generally good, however further to the west of the city, the land was higher, and the difference in height between places such as Soho and New River Head was insufficient to provide a good supply to new developments.

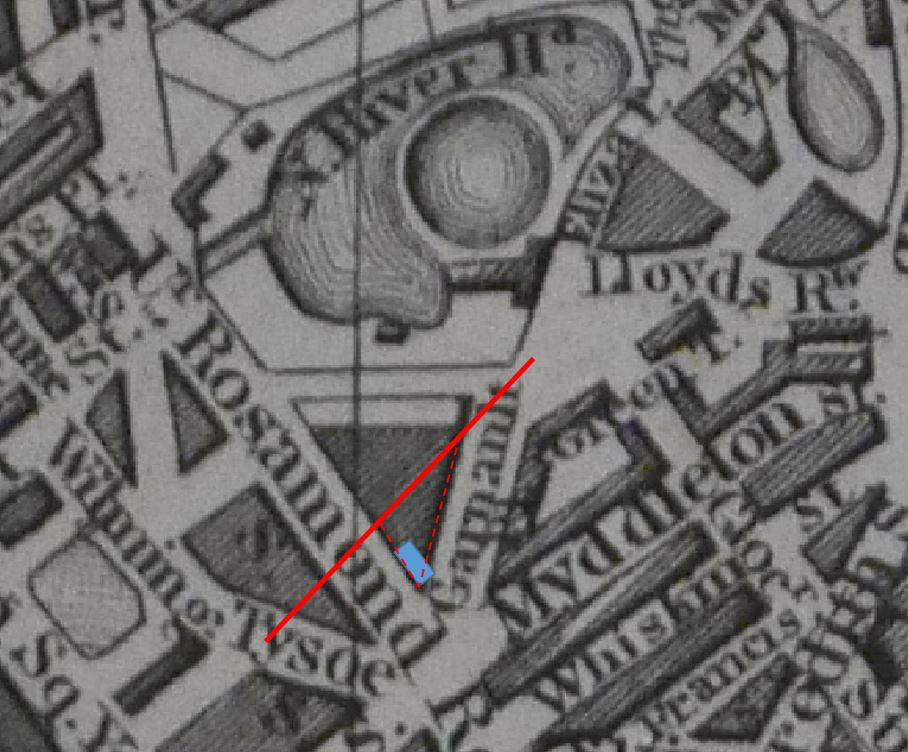

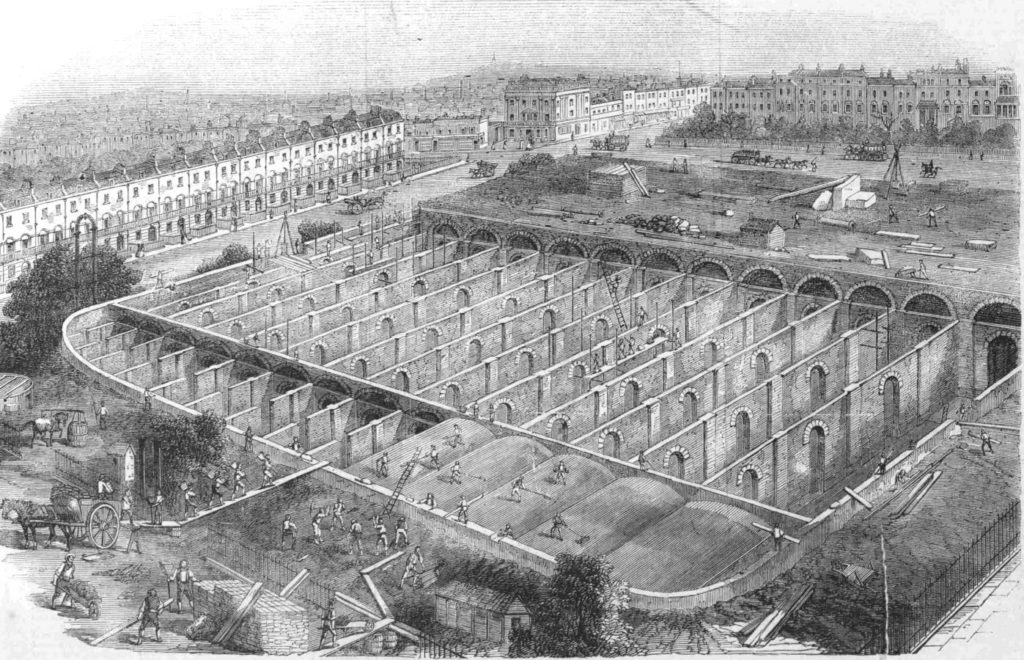

This is when the windmill appeared. The New River Company built a new reservoir at Claremont Square, towards Pentonville Road. This new reservoir provided extra storage capacity, and was also higher than New River Head, thereby able to deliver water at greater pressure.

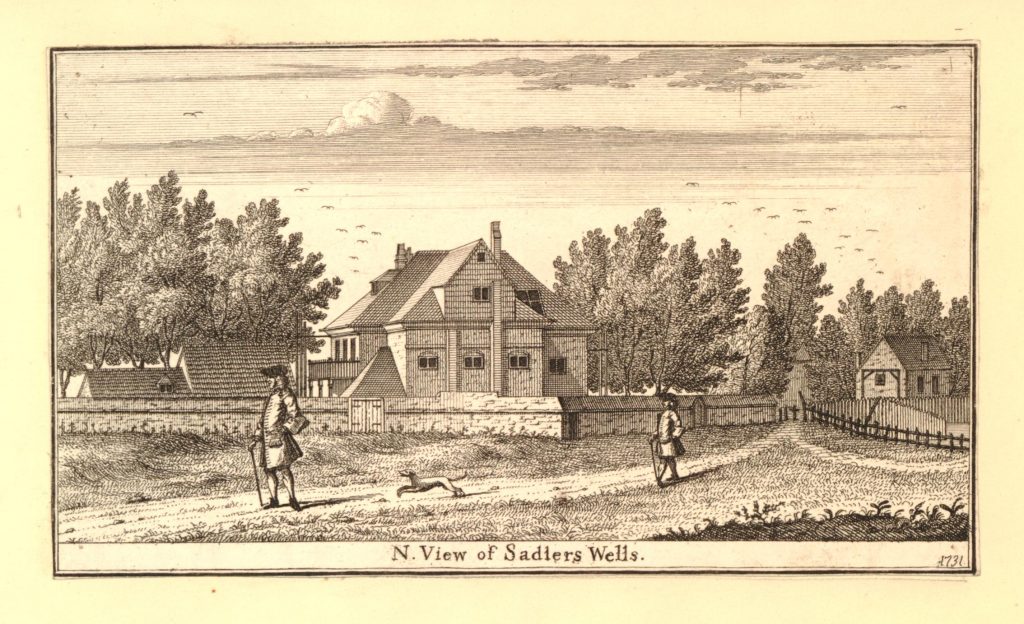

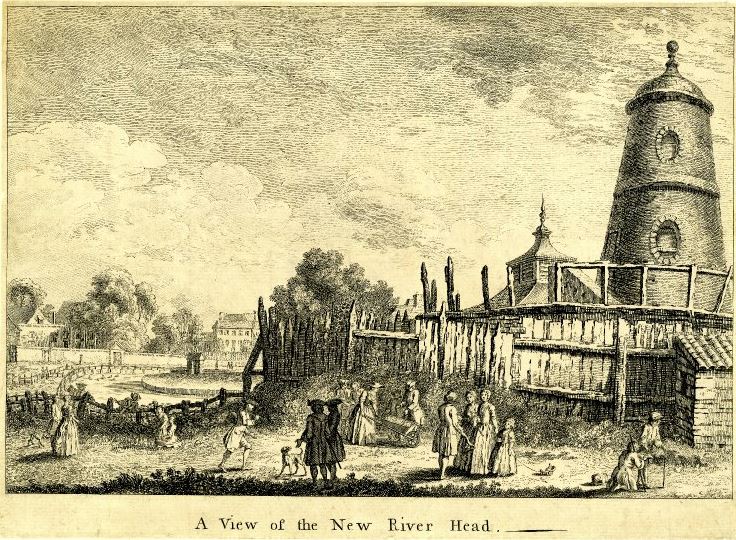

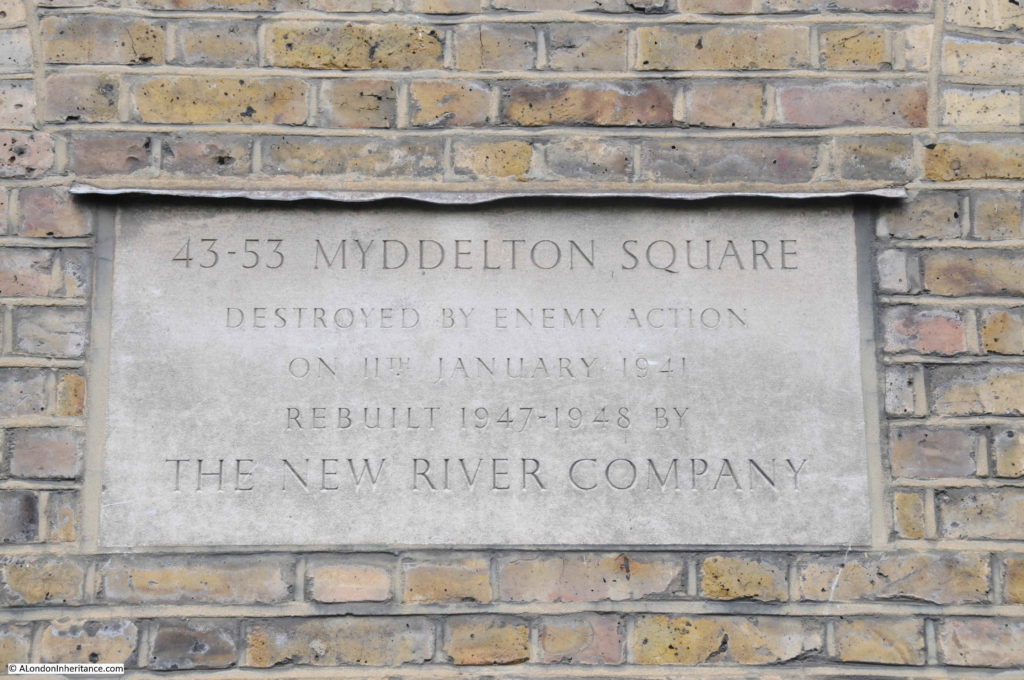

A method was needed to pump water to the new reservoir and the method chosen was a windmill. This was in operation by 1709, but was never very efficient and the top of the windmill was severely damaged by a storm in 1720. Newspaper reports of the storm refer to “the upper part, quite to the brickwork, was blown of the Windmill at New River Head”

The storm also damaged large numbers of ships anchored in the Thames, and: “The Horse-Ferry boat, that passed to and fro from Greenwich to the Isle of Dogs was lost and is not yet found, and the Storm was so violent as to lay the Isle of Dogs under Water by the beating of Water over the Banks”

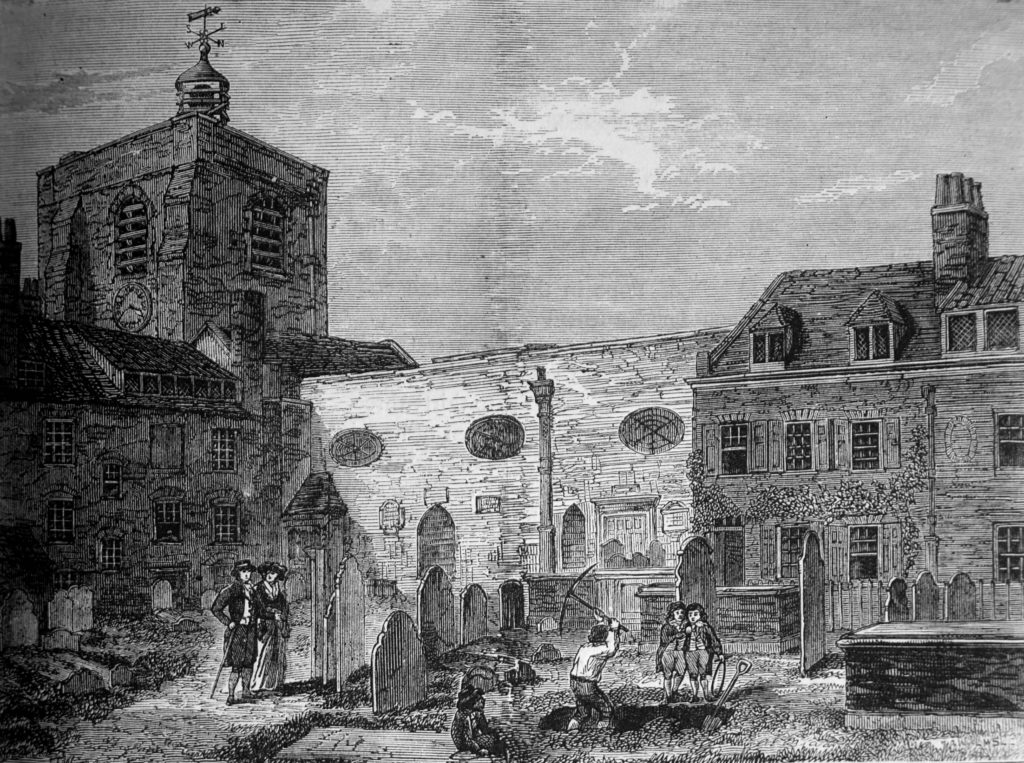

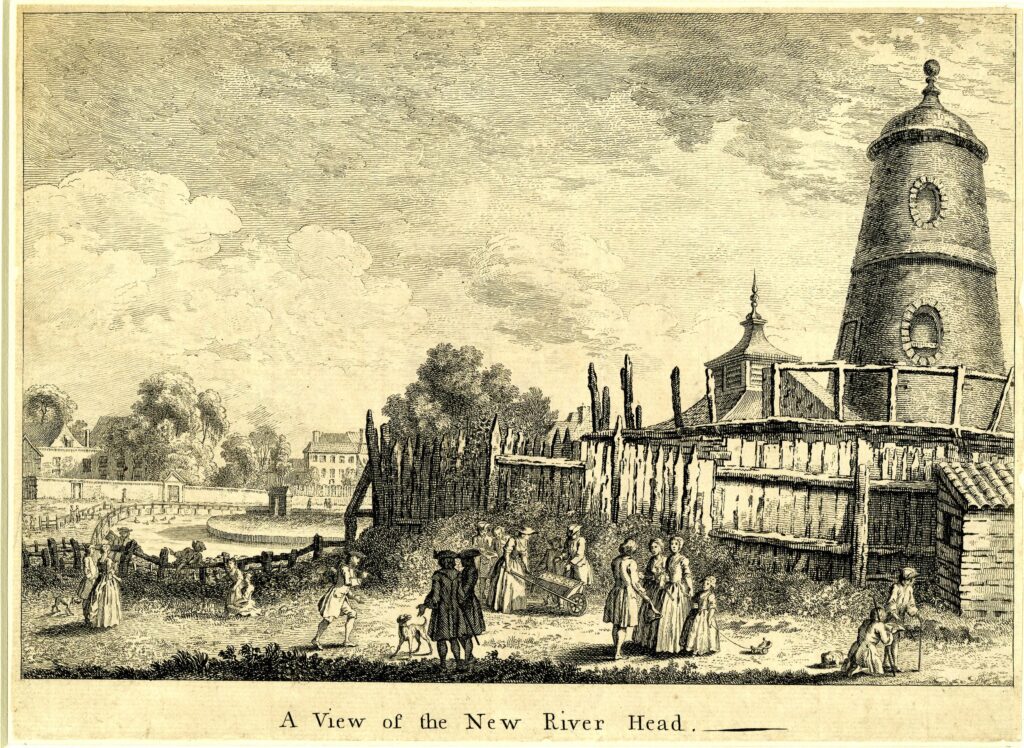

The following print shows the windmill in the 1740s with the sails and top section missing after the storm (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

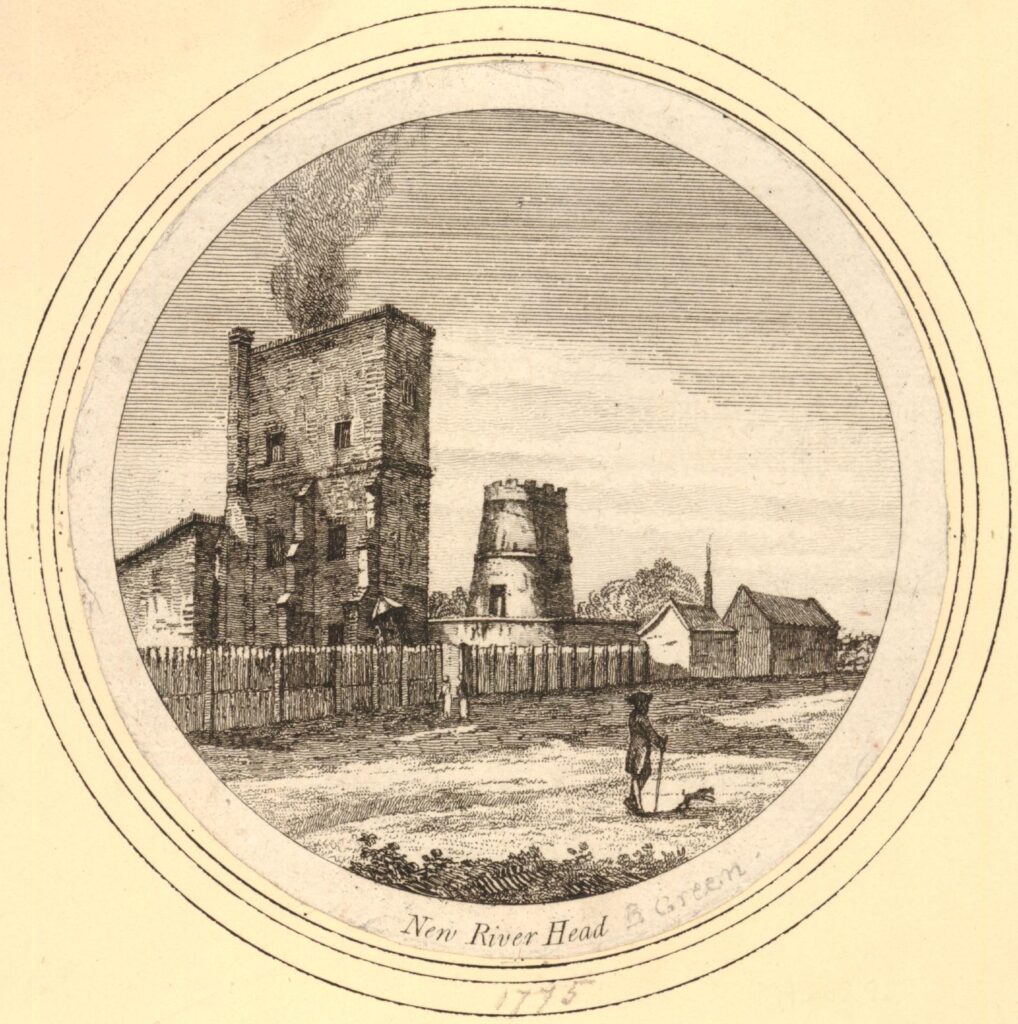

By 1775, the top of the windmill appears to have been castellated. The first engine house is in operation to the left. The engine house replaced the windmill and later horse power by providing the power for the pumps. (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The following print from 1752 shows the New River Head complex with the remains of the windmill after the 1720 storms (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

To the lower left of the windmill is a small building that would have housed the horse-gin, used between the storm and the installation of the steam engine to power the pumps, pumping water to the reservoir which can be seen in the lower part of the view.

If you look closely between the reservoir and the windmill, you can see what appears to be a couple of pipes running between the windmill and a building on the edge of the reservoir from where water is pouring into the reservoir.

Although now reduced to just the base, it is remarkable that part of the windmill has survived over 300 years, and it is the base of the windmill that we will see inside during the walk.

After the storm, a “horse gin” was employed which consisted of a small building adjacent to the windmill that provided room for a horse to walk in a circle whilst harnessed to a wheel. The rotation of the wheel was transferred to the pumps to provide the power to move water from New River Head to the higher reservoir.

Later in the 18th century, this was replaced by a steam engine. Whilst we will not be able to go into the engine house, we will walk alongside to explore the history of the building:

Credit: New River Head © Justin Piperger

Behind the engine house is a coal store used to store the fuel for the steam engines in the engine house. The following photo shows the coal store buildings on the left, with a storage area marked with dimensions on the right:

Some photos of the interior of the engine house:

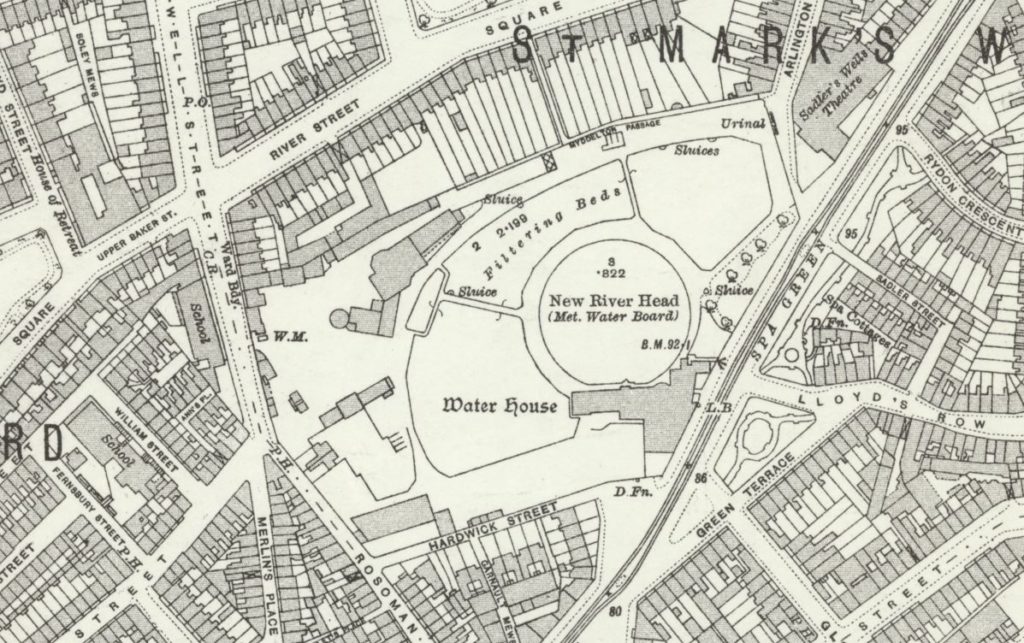

New River Head would continue to play a part in the supply of water into the 20th century.

Reservoirs eventually built at Stoke Newington were of the size needed for London’s ever growing population, and the New River would come to terminate at these reservoirs rather than continuing on to New River Head.

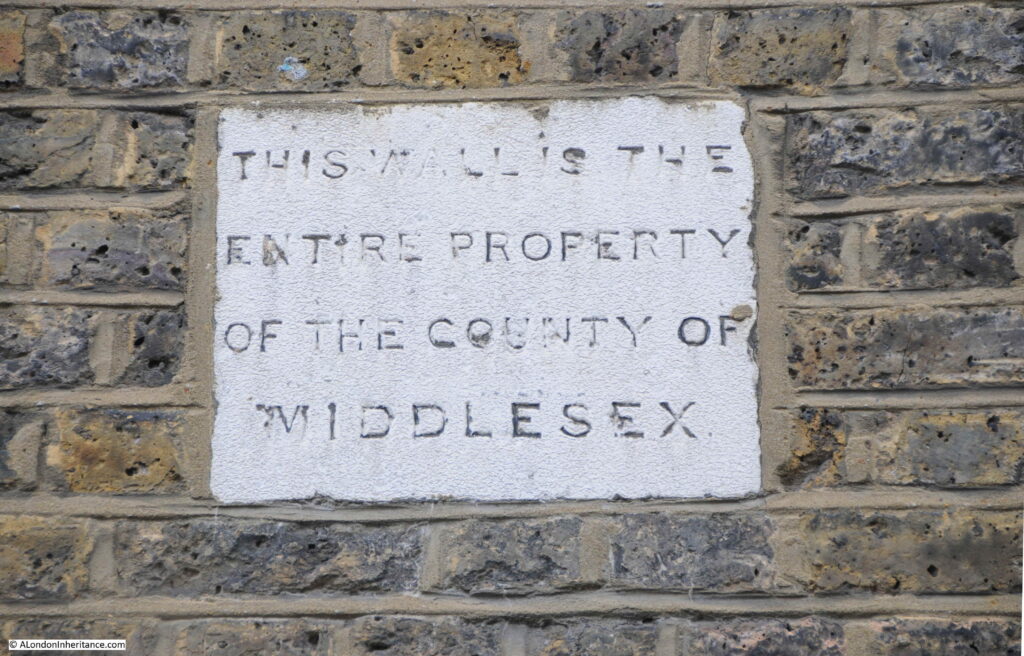

The central Round Pond was drained in 1913. The remaining filter beds had disappeared by 1946, and New River Head became the head offices of the Metropolitan Water Board, along with supporting functions including a large laboratory building.

New River Head continues to be a key part of London’s water supply with one of the shafts to the London Ring Main on the site. The shaft is one of the 12 main pump out shafts across the ring main where water is taken out and distributed locally.

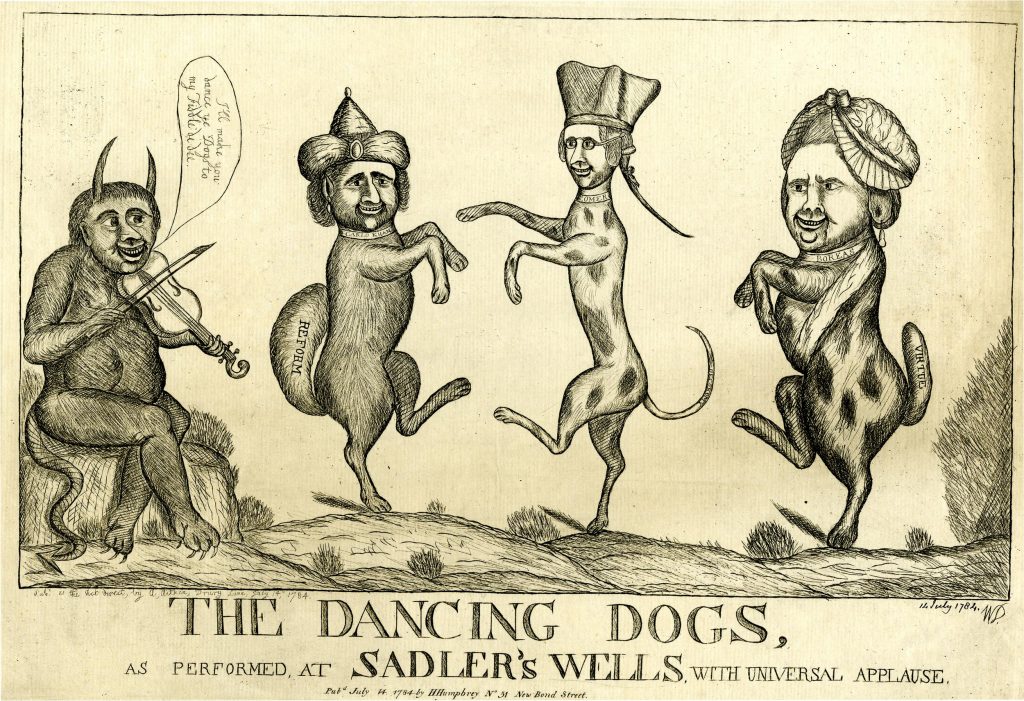

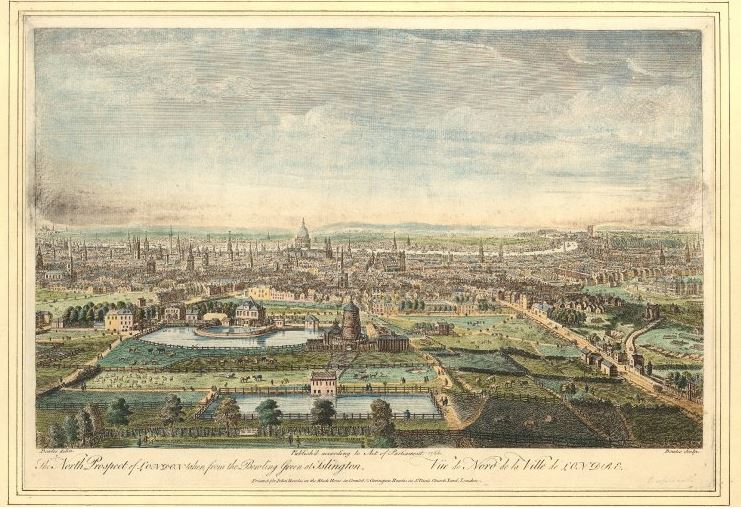

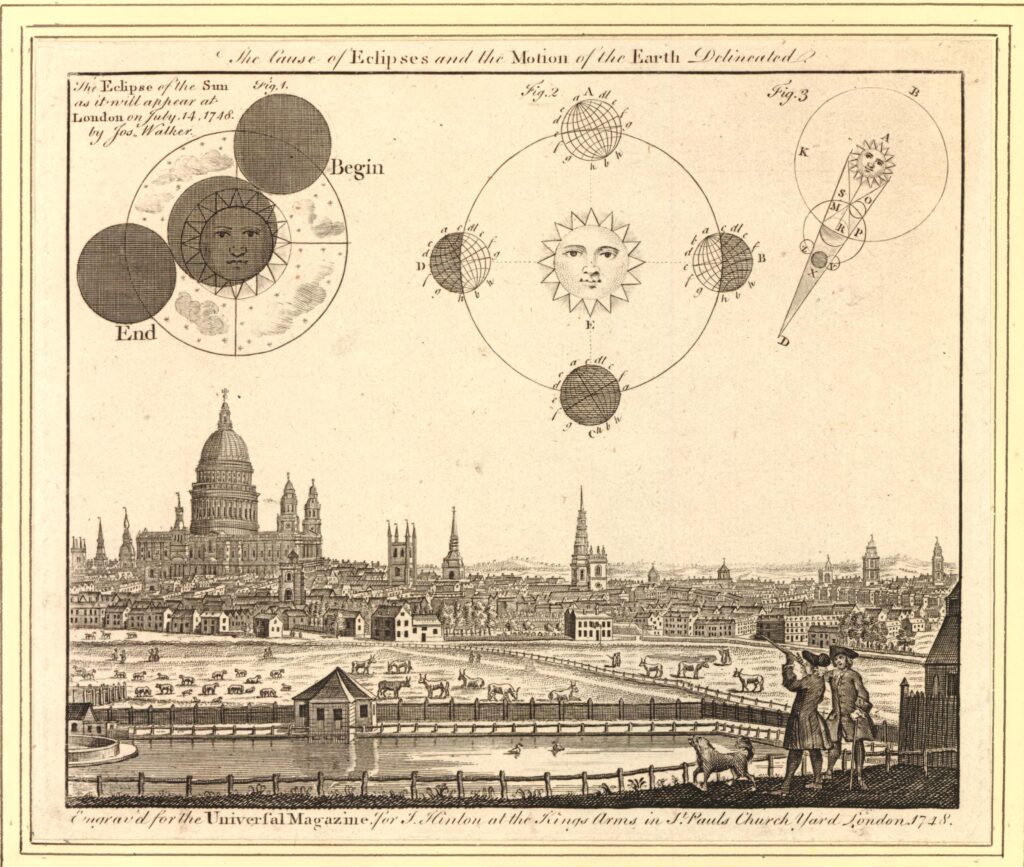

New River Head appeared in a 1748 print with astronomical drawings describing an eclipse of the sun. New River Head is at the bottom of the print, then fields and with the City in the distance (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

One of the two characters at bottom right is using a telescope, presumably to observe the eclipse which took place on the 14th July 1748.

The above print is the type of find that sends me searching for something that is not really related to the subject of the post, however as New River Head is in the view, there is a tenuous link.

The 1748 eclipse was an event well publicised in advance, and numerous papers published recommendations on how to view the eclipse, which sound very similar to what we would do today (apart from the candle).

1. Make a pin-hole in a piece of paper, and look through it at the eclipse. Or,

2. Hold a piece of glass so long over the flame of a candle, till it is equally blackened; and then the eclipse may be viewed through it, either with the naked eye, or through a telescope. Or,

3. Let the sun’s rays through a small hole into a darkened room, and so view the picture of the eclipse, upon a wall, or upon paper. Or,

4. Transmit the image of the sun through a telescope, either inverted, as usual on a circle of paper or pasteboard.

In London the eclipse would start at four minutes past nine in the morning and end at ten minutes past twelve. The eclipse was partly visible, however for much of the time it was obscured due to what were described as “flying clouds”.

I can guarantee that there will not be an eclipse at New River Head during the week of the walks, however the walks will provide a unique opportunity to view some of the buildings that contributed to the development of London’s water supply, learn about their future use, and to hear how water has influenced the development of Islington.