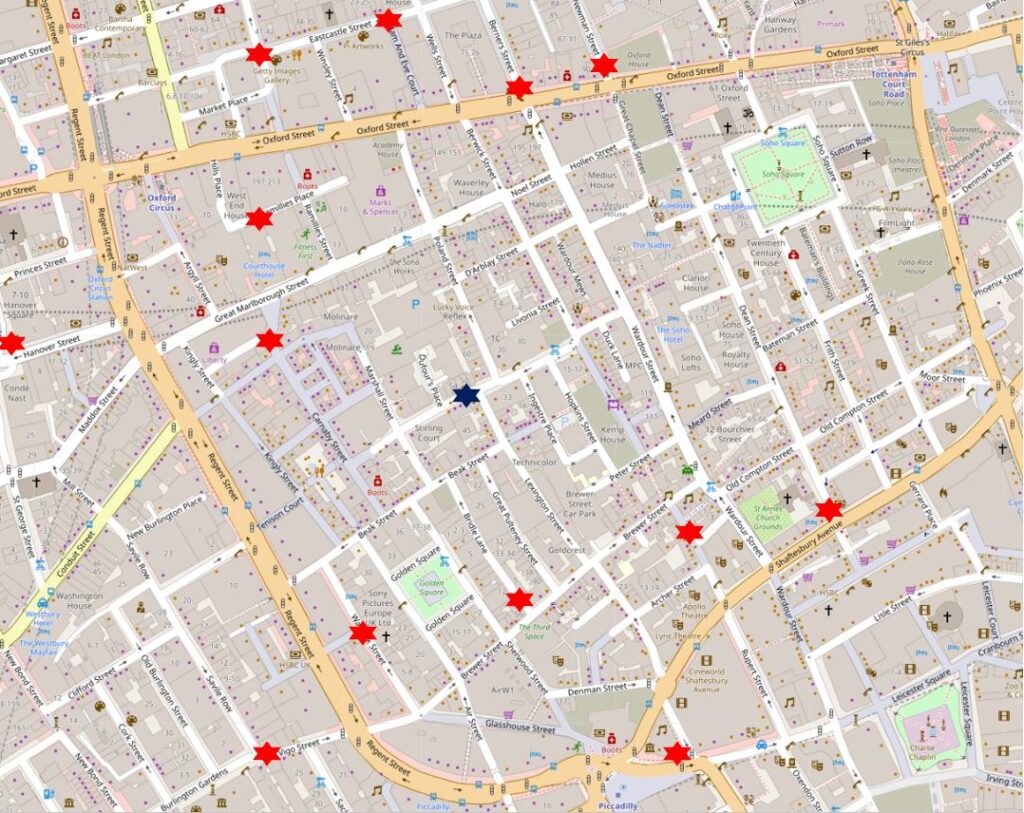

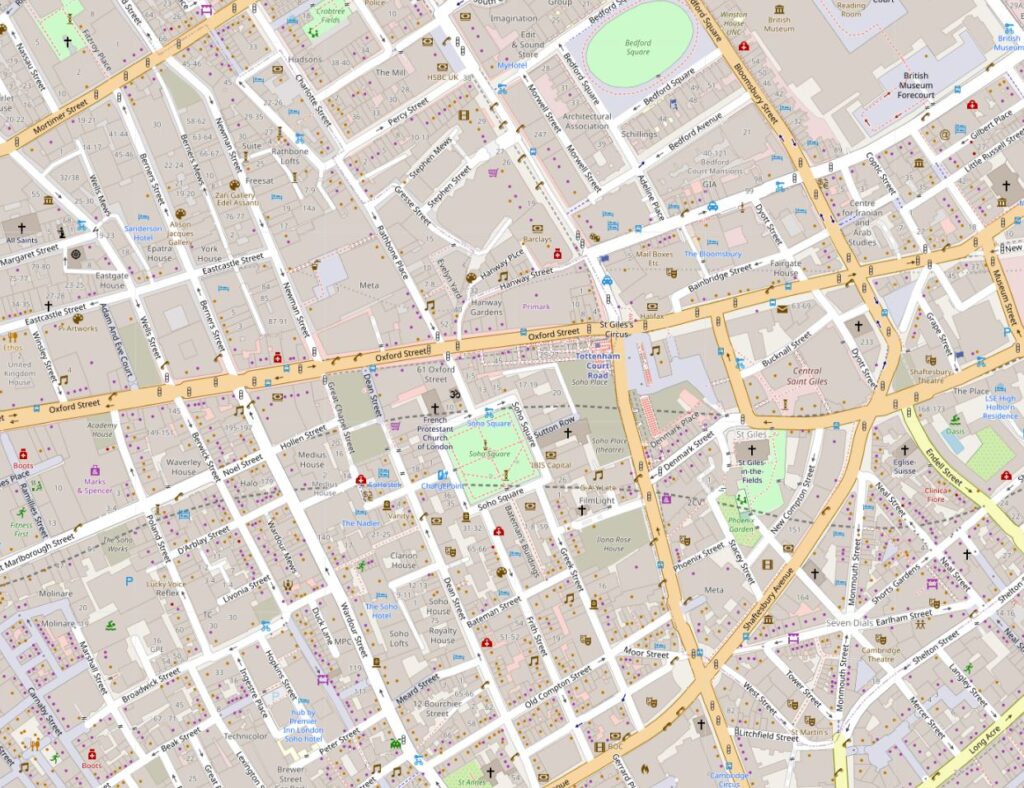

Soho Square can be found near the junction of Charing Cross Road and Oxford Street. A busy square, with lots of traffic, parking and occasionally it is used as a film set.

The centre of Soho Square is a large open space, and the square is surrounded by a considerable mix of architectural styles, reflecting the number of times that buildings have been demolished and rebuilt since the square was originally laid out, and the range of individuals. organisations and companies that have made the square their home.

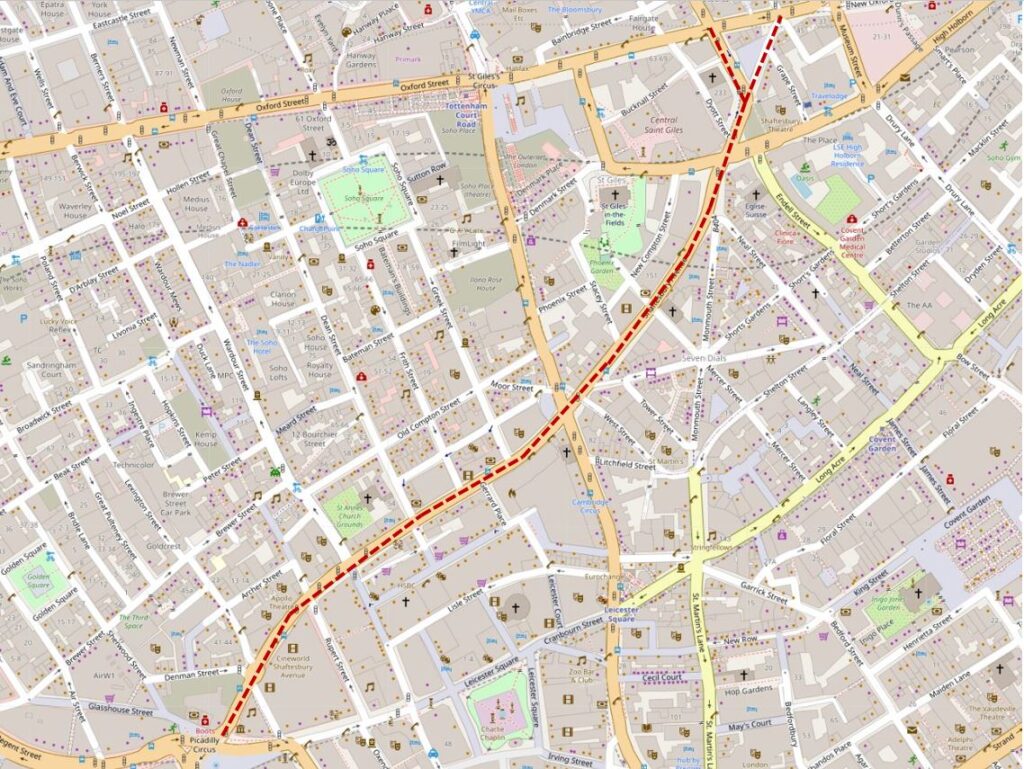

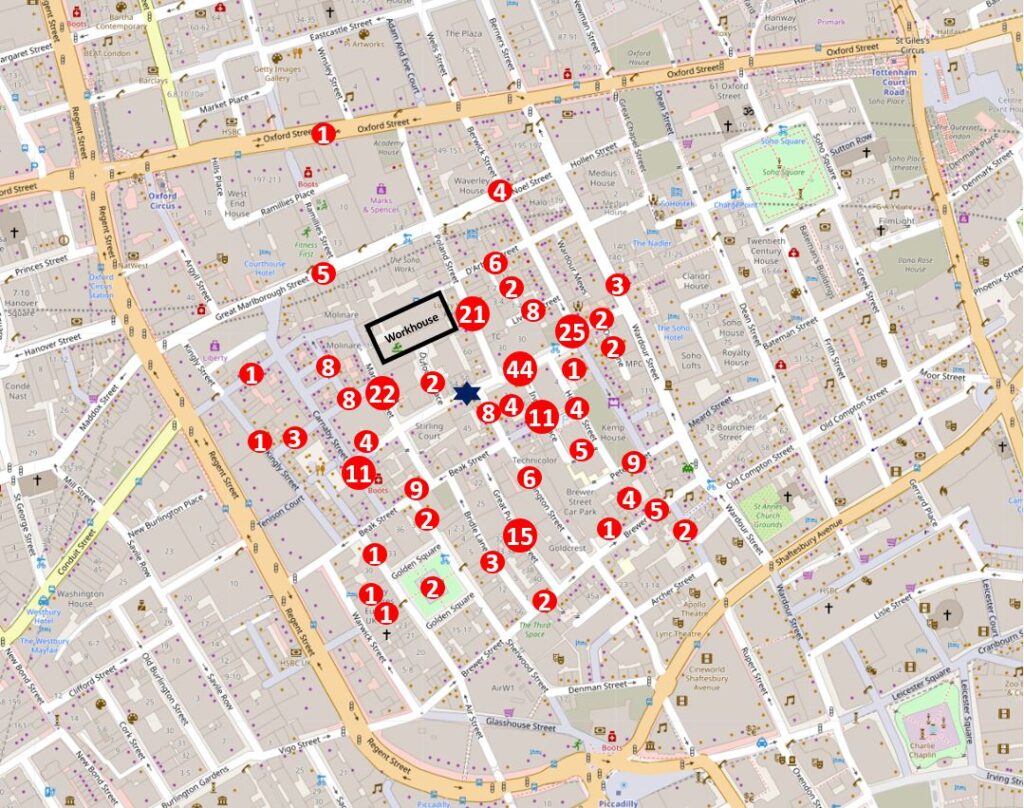

Soho Square is the rectangular green space in the centre of the following map (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

Soho Square was part of London’s northwards expansion and the first houses on the square were originally built around 1670.

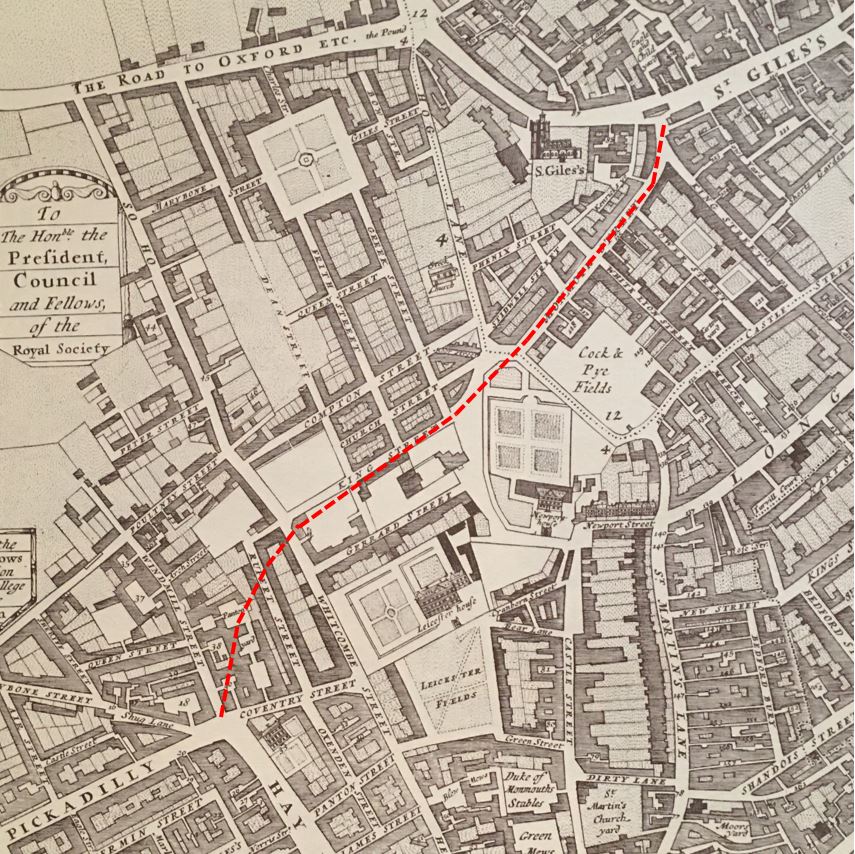

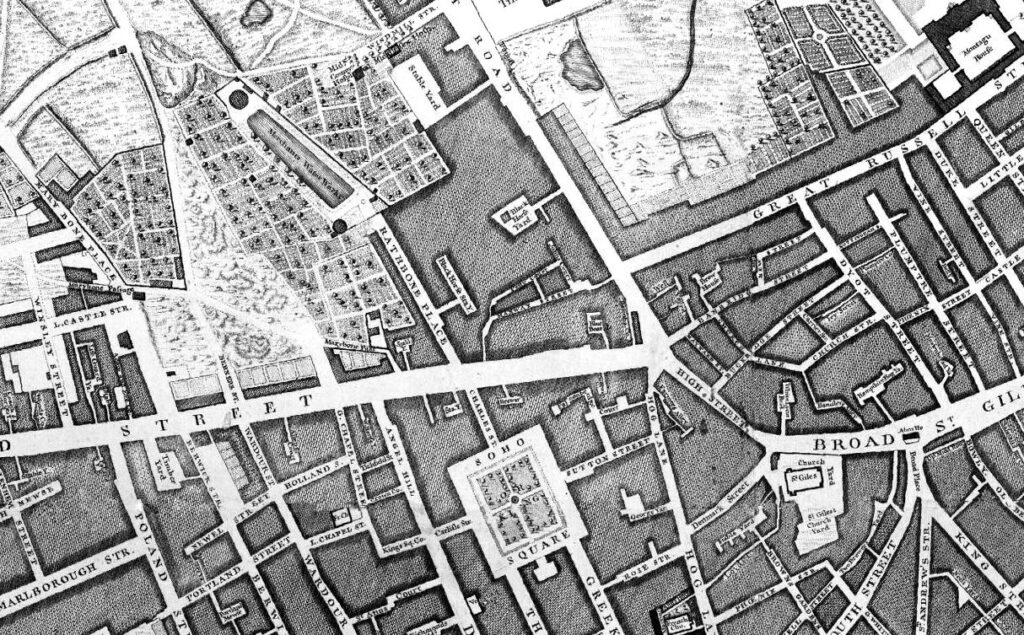

The following extract from Rocque’s 1746 map of London shows Soho Square, with Oxford Street to the north, but still much open space further north, which would be developed during the second half of the 18th century.

Soho Square, as well as many of the surrounding streets, was built on open space known as Kemp’s Field or Soho Fields.

The site of the square was leased to a bricklayer by the name of Richard Frith, who started construction of the first houses, with the first leases of these houses dating to the 1670s and 1680s.

The square was originally called King’s Square, presumably after Charles II, who was on the throne during the early years of the square’s construction. It would keep this name until the first decades of the 18th century, when it would gradually become known as Soho Square, with formal recognition of the new name of the square on maps such as Rocque’s in 1746.

Today, only a couple of the original houses remain, although in a much modified state.

Soho Square has seen continual waves of development, and a walk around the square today reveals a large range of building size and architectural type. Some buildings are on the original narrow plot, larger buildings have incorporated several adjoining plots of land.

On a weekday, the square is a hive of activity. There is a considerable amount of traffic through the square, parking along both sides of the road around the square, and on the day of my visit, filming had taken over one side of the square.

The open space in the centre of the square was separate from all this activity, and provided a space to look at the buildings surrounding the square before being blocked by leaf growth on the trees.

The following photo is looking to the east, with the tower block of Centre Point in the background.

The brick tower in the background is part of St Patrick’s Catholic Church. During the first years of the square, there were a number of large houses leading back from the square, one of these was Carlisle House, which was built by the Earl of Carlisle around 1690.

Carlisle House was leased by Father Arthur O’Leary, a Franciscan Friar, who managed to raise sufficient financial support from a number of wealthy Catholic families.

The house was converted so that it could be used as a place of worship, and was consecrated on the 29th of September 1792. It was one of the first Catholic places of worship opened after the Catholic Relief Acts of 1778 and 1791, which removed many of the restrictions placed on the Catholic faith during the reformation.

The current church was built on the site of Carlisle House between 1891 and 1893.

In the centre of the square is a small wooden building:

The wooden building is Grade II listed, and is described by English Heritage as a “Garden arbour/tool shed”. It was built around 1925 for the Charing Cross Electricity Company to provide access to an electricity sub-station below ground. It did not serve this purpose for too long as the underground space would become an air raid shelter during the Second World War.

The electricity substation was not the first utility to be built in Soho Square.

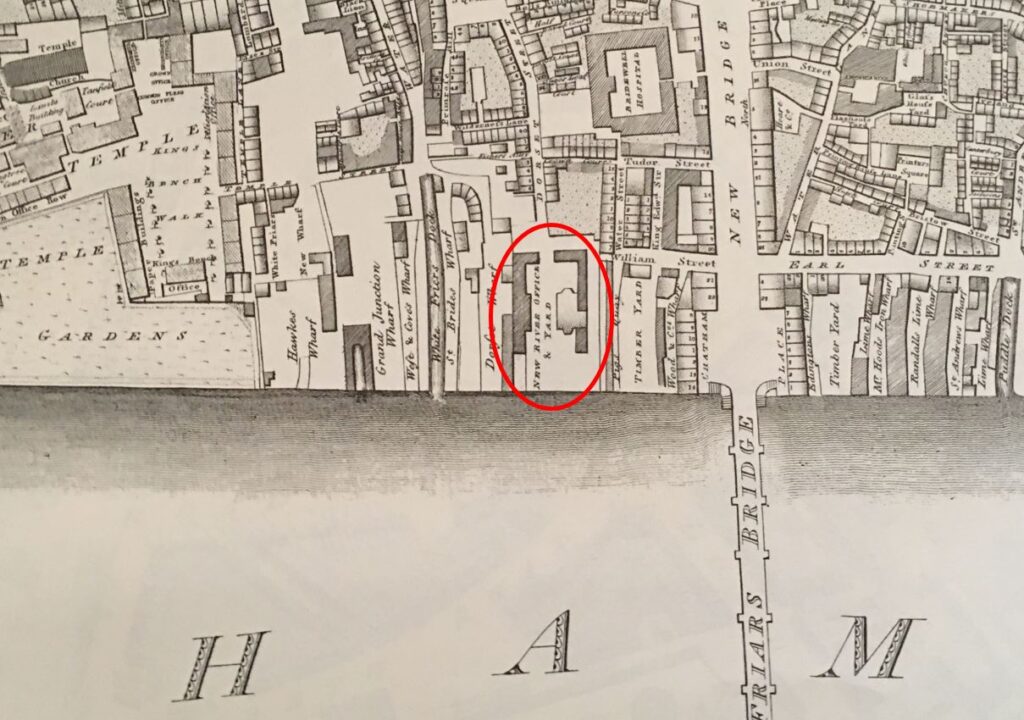

When the first houses in the square were built, there was competition from the water companies that served London to provide water. One of these companies was the New River Company who supplied water from their reservoirs at north Clerkenwell.

Whilst the supply worked to the City, Soho was on higher ground, and this small difference in height between the reservoir and Soho Square, along with the haphazard way in which the water distribution system had grown, resulted in a poor, low pressure supply to the new houses of Soho Square.

Sir Christopher Wren was asked to help with understanding the problems of distributing water to Soho Square and the developing area of the West End, however Wren looked at the whole system and recommended that the problems could only be addressed by effectively replacing the entire system with a new, integrated design.

The New River Company also commissioned John Lowthorp (a clergyman, who was also a member of the Royal Society) to look at the distribution problems,

Lowthorpe established that it was not water supply problems to New River Head (indeed the New River supplied enough water for the whole of London), as with Wren, Lowthorpe identified the distribution network and the organisation of the company.

This would only be fixed over a number of years, one of the short term fixes was the construction of a cistern in Soho Square to store water from the New River Company’s reservoirs for onward distribution.

The north east corner of the square:

The north west corner of the square:

The above two photos show the range of different buildings around the square, and the changes in building height and roof line.

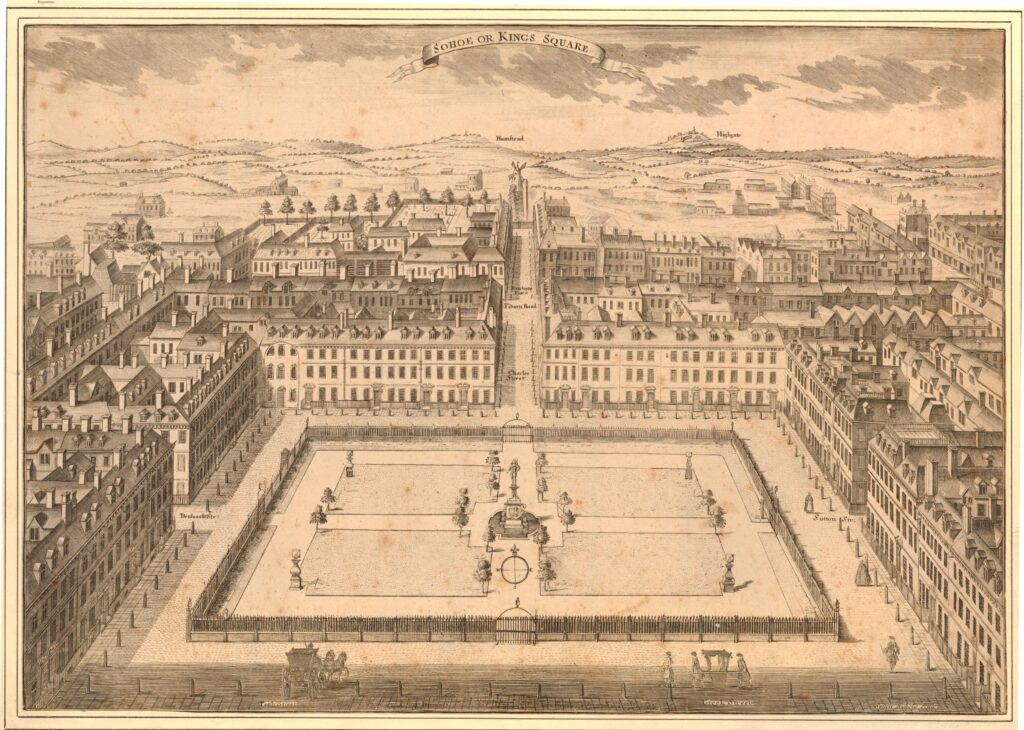

This is very different to when the square was built, as this print from around 1725 shows, with terrace housing lining three sides of the square (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

The view is looking north, and shows that in the first decades of the 18th century, Soho Square was really on the northern edge of the built city. The name of the square at the top of the print uses the original name of King’s Square, as well as the future name of Soho Square.

The hills in the distance are those of Hampstead and Highgate, and the street running north from the square crosses Tiburn Road.

This would later be renamed Oxford Street, and was named Tiburn Road as it led to the Tiburn or Tyburn tree or gallows at the western end of Oxford Street, at the junction of Oxford Street with Edgware Road and Bayswater Road.

The above map uses the spelling of Tiburn, rather than the more common Tyburn. Rocque also uses the Tiburn spelling for the street and the gallows.

By the time of the above print, the centre of the square had been laid out as formal gardens.

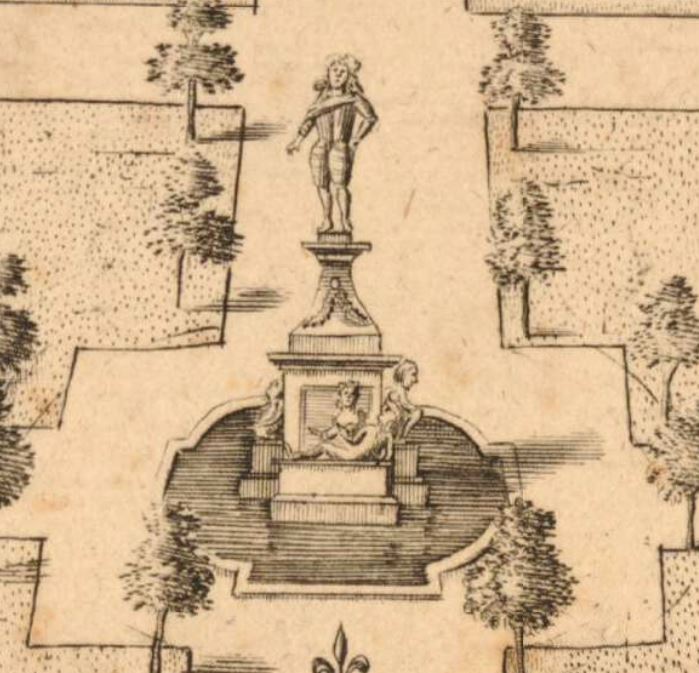

A statue can just be seen in the centre of the above print. I have enlarged this below:

The statue is of Charles II, above a fountain with a small surrounding pond.

Old and New London included a description of the statue and fountain:

“In the centre was a fountain with four streams. In the middle of the basin was the statue of Charles II, in armour, on a pedestal, enriched with fruit and flowers; on the four sides of the base were figures representing the four chief rivers of the kingdom—Thames, Severn, Tyne, and Humber; on the south side were figures of an old man and a young virgin, with a stream ascending; on the west lay the figure of a naked virgin (only nets wrapped about her) reposing on a fish, out of whose mouth flowed a stream of water; on the north, an old man recumbent on a coal-bed, and an urn in his hand whence issues a stream of water; on the east rested a very aged man, with water running from a vase, and his right hand laid upon a shell.”

Old and New London also comments that “the statue is now so mutilated and disfigured, and the inscription quite effaced”. There is also a comment that the statue could be the Duke of Monmouth (who we will come to later), rather than Charles II, however the consensus seems to be that it is the king rather than duke.

The statue was removed around the time that Old and New London was published. An article in the Illustrated London News on the 26th February 1938, records what happened to the statue, and its eventual restoration to the square:

“The statue of Charles II, by Caius Gabriel Cibber, the father of Colley Cibber, Poet Laureate, actor and dramatist, has been restored to Soho Square after an absence of sixty-two years. It was placed in the Square, then called King’s Square, during Charles II’s reign and surrounded a fountain bearing the emblematical figures of the Thames, Severn, Tyne and Humber.

In 1876 it was in such a bad condition that it was taken down and removed to Mr Goodall’s residence at Grims Dyke, Harrow Weald. There it was re-erected in the middle of a large pond, where it remained during the subsequent tenure of Sir. W.S. Gilbert. When Lady Gilbert died in 1936 she bequeathed the statue to the Soho Square Gardens Committee, who had it skilfully restored and have placed it on the north side of the Gardens.”

So although Charles II is no longer on his high pedestal, and the fountain and pond have long gone, he is back in Soho Square:

There is a small plaque near the northern entrance to the central garden that records an event in recent history.

Two trees can be seen in the following photo, with a small concrete block between them:

The plaque records that one of the trees (I assume the one on the right) was planted to replace a tree lost during the Great Storm over the night of the 16th to 17th October 1987:

On the north west side of the square, the French Protestant church glows red and orange in the low sun of an early spring day. The church was built in 1891 on the land released when two of the original houses on the square were demolished.

The following photo shows the rather wonderful, number 3 Soho Square:

The building is very narrow compared to many of the other buildings on the street, and although it is the third building on the site, the width of the building is because it is on the same plot of land as the original house when the square was first built.

The first house was built in 1684, it was rebuilt in 1735, which in turn was demolished for the current building which dates from 1902. The mix of the concave upper floors with the large bay windows on floors one and two, along with subtle decoration make number 3 one of the more interesting of the 20th century buildings on Soho Square.

To the right of number 3, is a single building that now occupies the space of numbers 4 to 6, the corner brick building shown in the following photo:

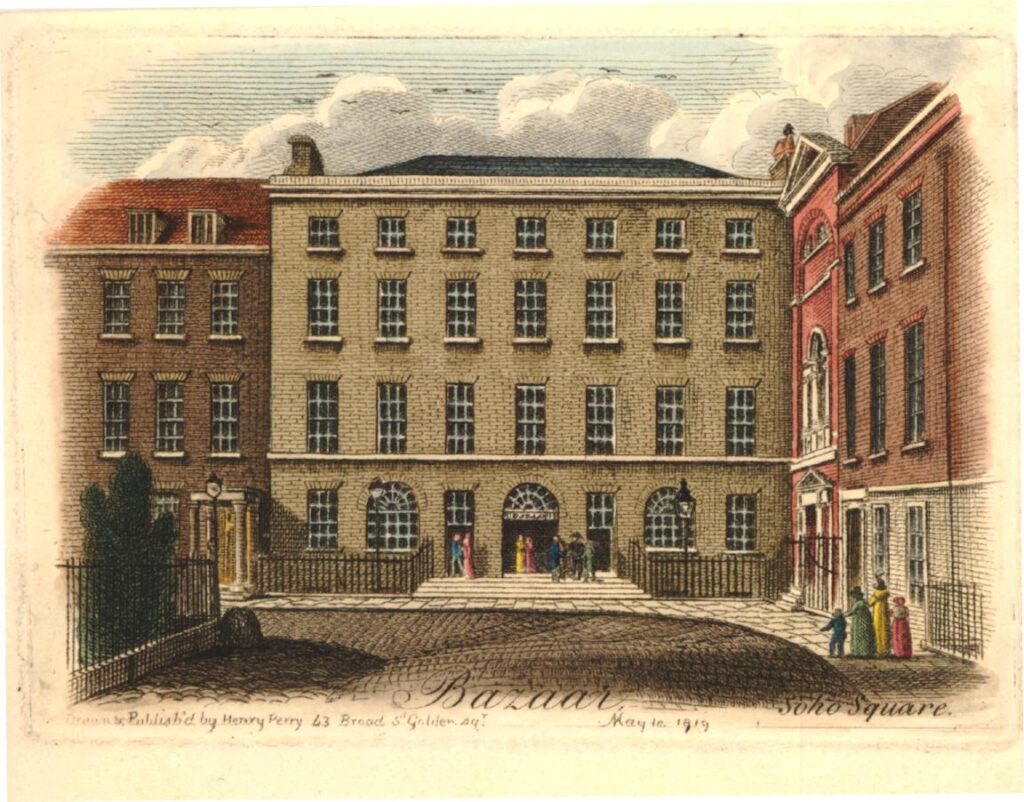

The building was originally constructed as a warehouse in 1804 by John Trotter, a contractor for army supplies.

With the end of the Napoleonic Wars, just eleven years after the warehouse was completed, John Trotter converted the warehouse into the Soho Bazaar.

The Soho Bazaar was a market place for a wide range of goods, and the bazaar would last for much of the 19th century. A newspaper report from the later years of the bazaar provides a good description of what could be found inside, and also why the bazaar was under pressure from the shops opening on nearby Oxford Street, and across the city. Published on the 17th of October, 1885:

“It is a long time since I walked round the Soho Bazaar, for the pretty stalls there have been greatly superseded by the many fancy shops that are now everywhere in London. but the old place, though somewhat changed in character, is the depot for many specialties which of themselves would not pay if a whole shop had to be hired for their sale.

All sorts and kinds of fancy work, of contrivances for the comfort of invalids, and such like inventions are to be seen, and, moreover, there is a large register office for domestic servants and convenience for interviews with them, in connection with the bazaar, and one great recommendation of it to me is that all the stall holders are women, not flighty girls, and they are attentive and pleasant to inquirers or purchasers of their own sex, and not on the look out for a possible flirtation, which is the great drawback to most bazaars.

I went there the other day to see myself the ladies work stall, and its appearance is most encouraging, for the work I saw was well executed, attractive, and useful. Every lady who desires to sell her work there is expected to pay a fee of a guinea a year for expenses.”

The stalls in the bazaar seem to have sold all manner of homemade products, and there was also a kindergarten, where babies were given special rugs to play / crawl on. The rugs had cutout animals and other figures to attract attention.

The following print shows the Soho Bazaar in 1819, soon after opening (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Compare the above print with my 2022 photo of the building, and although the ground floor has been significantly remodeled, the upper floors are the same, after 200 years.

On the south side of the square is the Hospital for Women, which combined / rebuilt houses already on the site:

At the very top of the left building of the hospital, is the date “Founded 1842”. This refers to when the hospital was originally founded in Red Lion Square as the Hospital for the Diseases of Women, before moving to Soho Square in 1852.

Records in the National Archives state that “The Hospital was closed in 1939 on the outbreak of war, and a First Aid Post was opened in the Outpatients Department by Westminster City Council”, and that in 1948, the hospital “was amalgamated with St. Mary’s Hospital and The Hospital for Women became part of The Middlesex Hospital Group”.

The first building on the site of the Hospital for Women, was one of the earliest buildings to face onto Soho Square.

Monmouth House was built for the Duke of Monmouth, however he seems to have spent very little time there.

After Charles II’s death, Monmouth led a rebellion with the aim of taking the throne. He was defeated at the Battle of Sedgemoor on the 6th of July 1685. After capture, Monmouth was executed on Tower Hill on the 15th of July 1685.

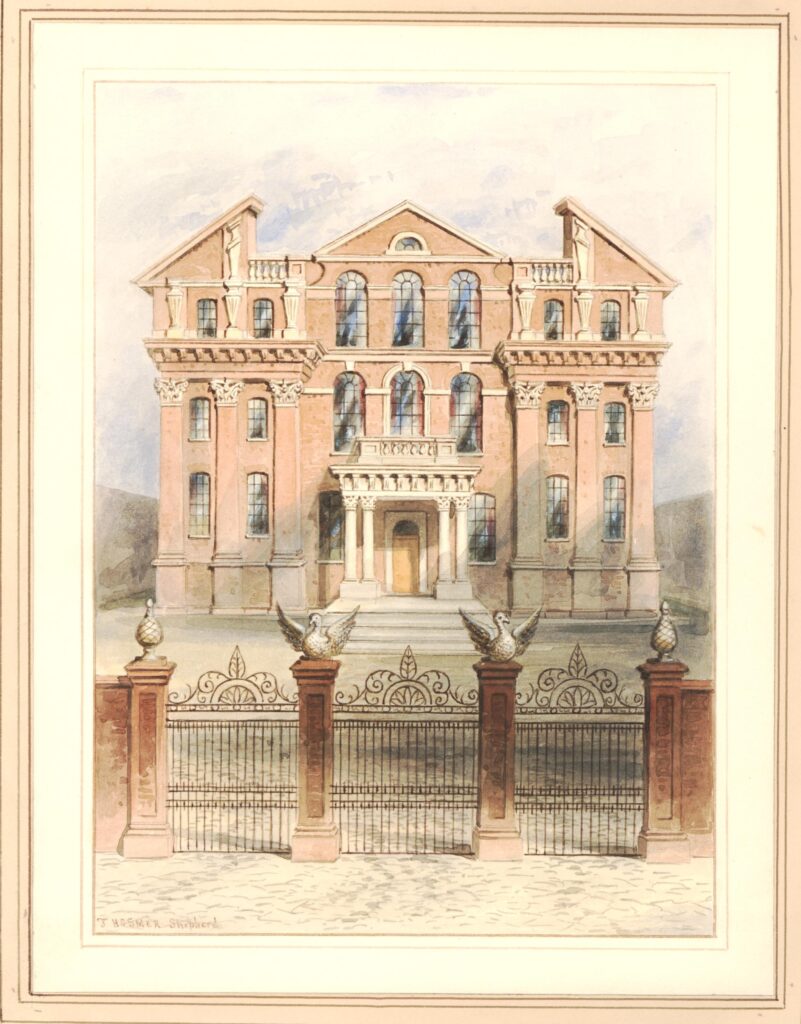

Monmouth House (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The house was sold after Monmouth’s death, converted to auction rooms in 1717, and demolished in 1773.

The house on the south east corner of Soho Square, at the junction with Greek Street, is the House of Charity / House of St Barnabas.

On the day of my visit, it was being used as a film set:

Despite appearances, the building is not one of the original houses on the square. The house we see today was completed in 1747 after the original house on the site was demolished.

The building was used by one of the organisations that would eventually become the GLC. In 1811, the Westminster Commissioners of Sewers occupied the building, then the Metropolitan Board of Works who stayed on Soho Square until their move to Spring Gardens, before moving to County Hall on the South Bank as the London County Council.

When the Metropolitan Board of Works moved out, it was sold to the House of Charity, which had been established in 1846 for the relief of the destitute and the homeless poor in London.

Now the House of St Barnabas, which works to get people into secure, paid employment, through training and support. The interior of the building still has many of the original features, and is why the building is attractive as a film set.

To the west of the square, Sutton Row provides a route to Charing Cross Road, and St Patrick’s Catholic Church is on the right:

On the left is Grade II listed, number 21 Soho Square, an 1838 / 1840 rebuild of the original house on the site, which, during the late 18th century had, as Old and New London tactfully described, been a “place of fashionable dissipation to which only the titled and wealthy classes had the privilege of admission”, basically a high-class brothel.

After being rebuilt, the building was taken on by Crosse & Blackwell, and numerous 19th century adverts give Soho Square as the address for Crosse & Blackwell – manufacturers of Pickles, Sauces & Jams etc.

There are three interesting buildings in the north-east corner of Soho Square. The building on the right in the photo below is one of the original houses on the square. Although considerably modified, it does give an indication on what the terrace houses would have looked like as the square was completed.

The centre house has a blue plaque, recording that Mary Seacole lived in the house:

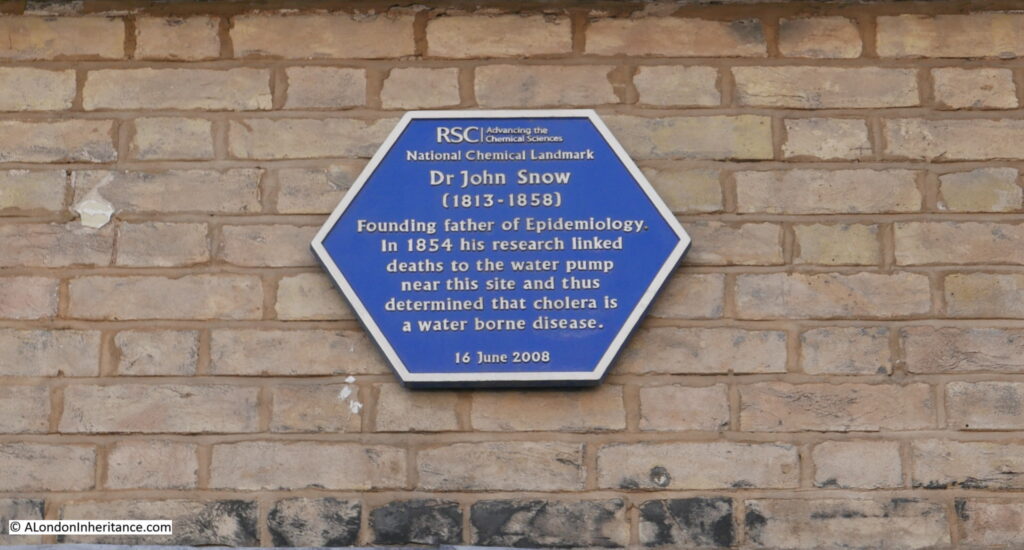

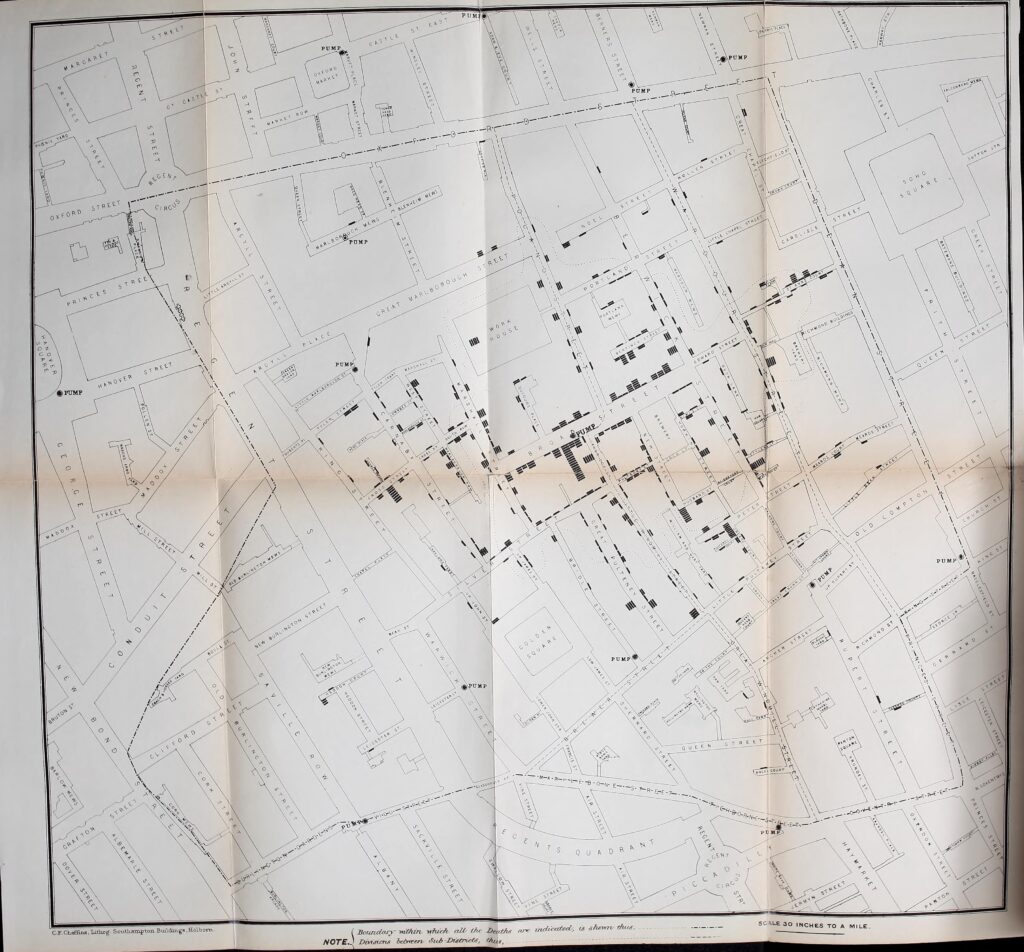

Mary Seacole was a Jamaican nurse who learnt many of the local techniques for practicing medicine. She traveled widely, and was involved with the treatment of people suffering from cholera outbreaks in Jamaica and Panama.

In 1853 she was responsible for nursing services for the British Army in Jamaica, however she had heard about the suffering of soldiers in the Crimean War, and asked that she be sent to the Crimea to work as an army nurse.

This request was not approved, so she funded her own trip to Crimea where she set up the “British Hotel” to provide a place of rest and treatment for injured and sick soldiers. This was the same war where Florence Nightingale was also working, but Mary’s British Hotel was closer to the front.

After the end of the Crimean War she returned to Britain, however she had very little money left, having funded the trip to the Crimea, and in 1856 she was declared bankrupt, as the Globe on the 7th November 1856 reported:

“The bankrupts, Mrs Mary Seacole and Thomas Day the younger, are described as of Tavistock-street, Covent-garden, and Ratcliff-terrace, provision merchants, and formerly of Balaklava and Spring Hill, front of Sebastopol. Mrs. Seacole is a lady of colour, and has been honoured with four government medals for her kindness to British soldiery. She was present in person, and attracted much attention, the gaily coloured decorations on her breast being in perfect harmony with the rest of her attire.”

Whilst in London, she wrote and published her biography, and a review sums up how she was viewed:

“The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs Seacole in Many Lands has just been published by Mr James Blackwood of Paternoster Row. Of Mrs Seacole, Dr. Russell says in a brief preface ‘If singleness of heart, true charity and Christian works; if trials and sufferings, dangers and perils, encountered boldly by a helpless woman on her errand of mercy in the camp and battlefield, can excite sympathy and move curiosity, Mary Seacole will have many friends and many readers’. Mrs Seacole’s autobiography is interesting, includes many strange episodes, and, we doubt not, will obtain numerous readers.”

Proceeds from the book, along with a fund raised by the Prince of Wales provided Mary with sufficient funding to live in comfort for the rest of her life. She died in London in 1881, and newspaper announcements of her death started with the headline “DEATH OF A DISTINQUISHED NURSE”.

Over the following decades, her name disappeared, with Florence Nightingale being more associated with the Crimean War.

A group of nurses from the Caribbean visited Mary’s grave at St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Cemetery in Kensal Green, and started to campaign for greater recognition for her. This was supported by the local MP to Kensal Green and in 2016, a statue was unveiled in the grounds of St Thomas’ Hospital on the south bank of the Thames just to the west of Westminster Bridge.

The large disk behind the statue of Mary is an impression taken from the ground in the Crimea where Mary Seacole worked to help soldiers during the Crimean War.

I cannot find out exactly when Mary Seacole lived in Soho Square. Newspaper reports of her life after she returned from the war mention a number of different addresses in London so she seems to have moved around.

Very little of the original Soho Square remains, the statue of Charles II, and a couple of the houses, although all have been repaired and modified, but the square does show how London streets have changed and adapted to different uses over hundreds of years, and how much there is to find in a London square.