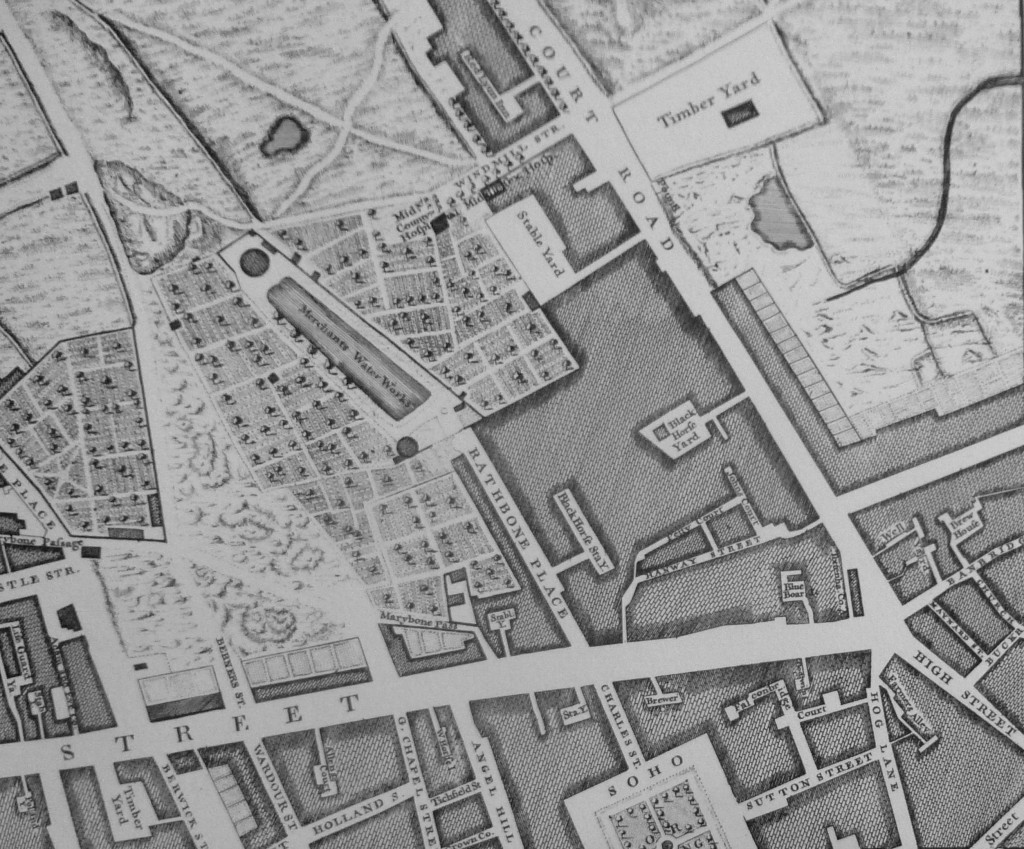

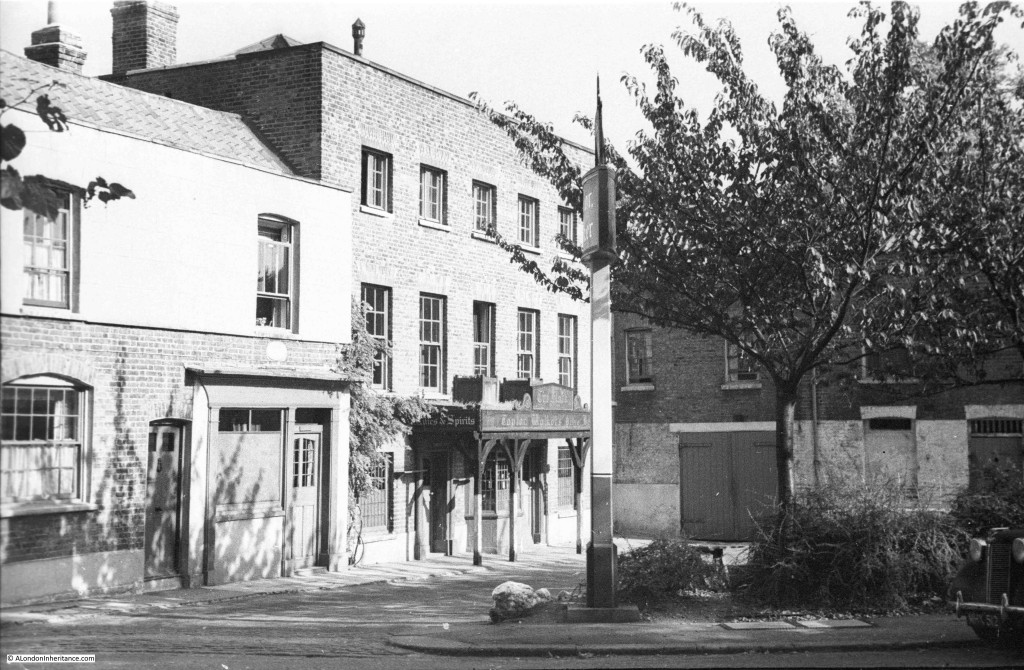

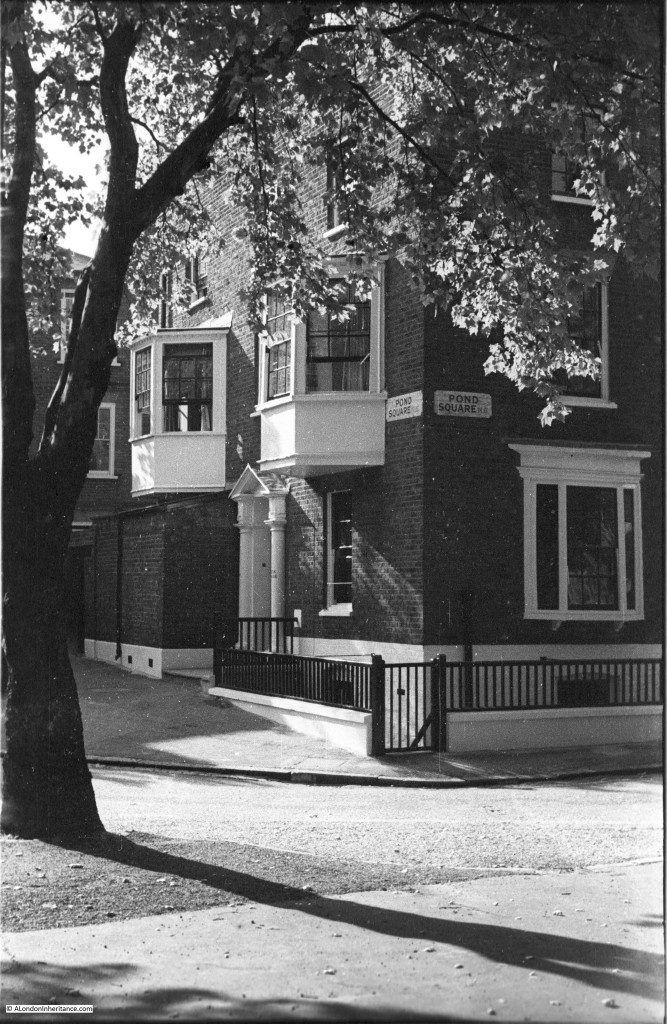

The following photo shows the junction of South Grove and Highgate High Street. The photo is one of my father’s and was taken in 1948:

The same view, 75 years later, in 2023:

It is remarkable that in 75 years, the buildings have hardly changed. There is now far more traffic, but perhaps the most significant change is the network of cables that were strung across the street in the 1948 photo.

The cables were to provide power for the trolleybuses that once ran up Highgate Hill.

London had both trolleybuses and trams. The key difference is that trams ran on rails, whilst trolleybuses ran on normal pneumatic rubber tyres and did not need tracks running along the road. They were therefore more flexible in movement, within the constraints of the overhead cables which provided the electrical power supply.

The photo was taken where South Grove meets Highgate High Street, and where the layout of the streets and space available provides a turning point for the trolleybuses at the Highgate end of the route.

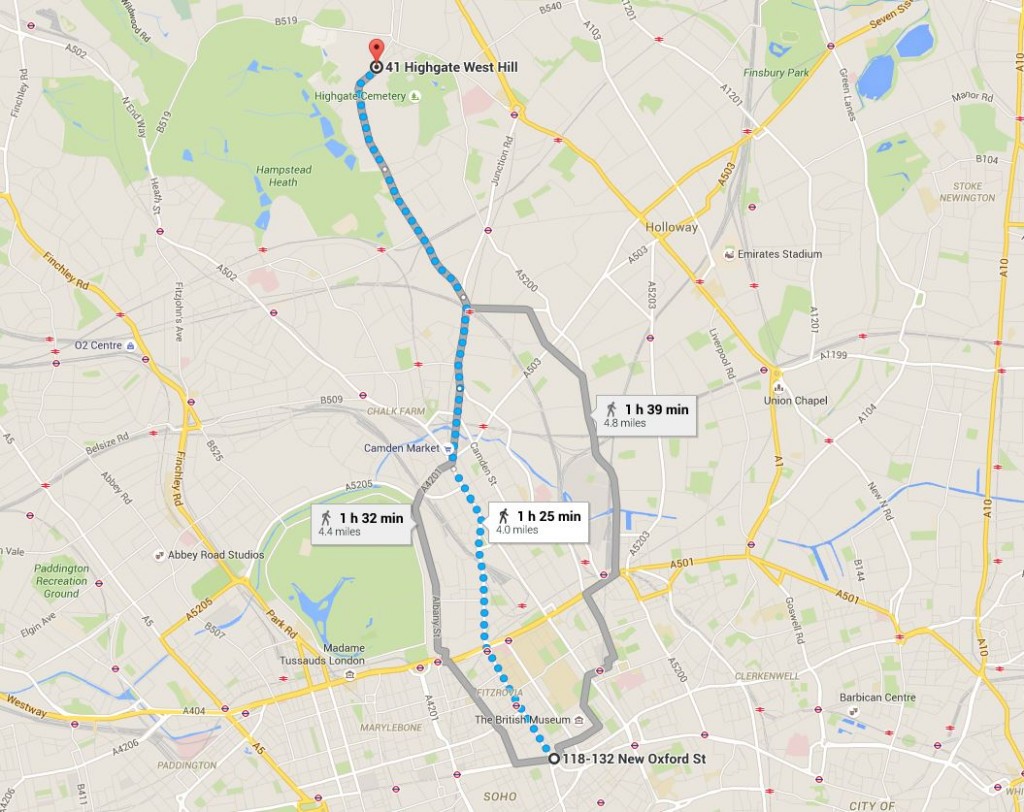

One of the reasons for using a trolleybus rather than a tram was the steep street that is Highgate Hill. The increase in height from Archway up to the point of the photo is 226 feet in a distance of 0.7 of a mile.

The rubber tyres of a trolleybus provide a much better grip than the metal wheels and tracks of a tram, which may well have had problems trying to maintain grip whilst ascending or descending Highgate Hill.

It was the 611 trolleybus that served Highgate. The route of the 611 was between Highgate and Moorgate, with stops as follows::

- Moorgate: Finsbury Square

- Highbury Station

- Holloway: Nags Head pub

- Archway Station

- Highgate Hill: Salisbury Road

- Highgate Village: South Grove

During Monday to Friday, the 611 ran at a frequency of one every 5 minutes, with one every 4 minutes at peak times. On Sunday’s the longest time between 611 arrivals was 6 minutes, so it was a well served route, and ran from just after 7 in the morning until just after 11 at night.

It is a shame that my father did not take a photo of the 611 arriving and turning at the location of the photo. I do not know why he took the photo. It may have just been the architecture of the buildings and general street scenes, rather than a trolleybus, which would have been a normal sight across London in 1948.

Again, a theme throughout this blog is that it is the normal, everyday things that we take for granted, and are the things that will disappear and are worth a photo.

What did a trolleybus look like? I have not yet found a photo of one whilst scanning my father’s photos, but have found one on the Geograph site. The following photo was taken on the Romford Road at Manor Park, Ilford, and shows “two westbound trolley-buses, the front one being on Route 663”:

As can be seen from the above photo, a London trolleybus looked very much like a normal bus, but with the addition of the booms on the roof which took electrical power from the overhead wires. It was basically an electrically powered bus, and would be considered very environmentally friendly by today’s standards.

The trolleybus did not need the tracks in the street, which was a significant cost advantage for both the original construction and ongoing maintenance.

The trolleybus could move within the constraints of the booms, which rotated on the roof allowing the trolleybus to move around obstructions. Whilst this was a significant benefit in avoiding death and injury to pedestrians, it could also result in problems whilst manoeuvering, as this article from the Holloway Press on the 22nd of February 1952 demonstrates:

“Trolleybus Jammed: The crews of two L.T.E. breakdown vehicles worked for two hours on Saturday evening to free a No. 611 trolleybus which became jammed against scaffolding in Holloway Road, near Ronalds Road.

The crowded trolleybus driven by Mr. Thomas Kenefick of Lambton Road, Upper Holloway, collided with the scaffolding outside Messrs. G. Hopkins and Sons, engineers, after swerving to avoid a boy stepping off the pavement. The force of the impact burst the near-side tyre and smashed paneling on the top deck. Nobody was injured.”

The first London trolleybus service commenced in 1931, and a programme of replacement of trams by trolleybuses began, as they were far more economical and as illustrated by the newspaper article above, were a safer alternative when running along busy streets.

Trolleybuses lasted longer than trams on London’s streets, but from 1954, London Transport started to replace trolleybuses with diesel buses, and the last trolleybus ran on the streets of London on the 8th of May, 1962.

The Illustrated London News reported on the last day of the trolleybus: “The last 100 of the 1700 trolleybuses that once ran in London made their final runs on May 8th, before being honourably discharged. The changeover in South-West London began in 1959. London’s last trolleybus arrived at Fulwell, greeted by a large crowd at midnight.”

The last trolleybus service on the 611 route between Moorgate and Highgate ran on the 19th of July, 1960, after which diesel buses would take passengers up and down Highgate Hill.

In my father’s photo, there is a pub on the corner, as the street disappears down towards Highgate Hill. The pub is the Angel Inn:

The pub has an interesting plaque which states that Graham Chapman of Monty Python’s Flying Circus “Drank here often and copiously”:

The Angel Inn is a very old establishment, although the current building is relatively modern. The photo below shows the frontage of the Angel Inn on Highgate High Street:

There has been a building on the site from at least the fifteenth century, when it was known as the Cornerhouse. From 1610, and probably earlier, it was a coaching inn, and continued in this use for the next few centuries. There is a cobbled yard round the back of the Angel where horses would have been stabled.

The earliest written reference I could find mentioning the Angel was from the Oxford Journal on the 28th of June, 1755, when “On Sunday last, about five o’Clock in the Afternoon, the Roof of the Angel Inn in Highgate was split by the Thunder and Lightning, which was very violent about that Neighbourhood.”

The Angel was completely rebuilt between 1928 and 1930 which explains why this old establishment has such a modern appearance.

The previous version of the Angel was from around 1880, when a new façade had been added to a late Georgian building.

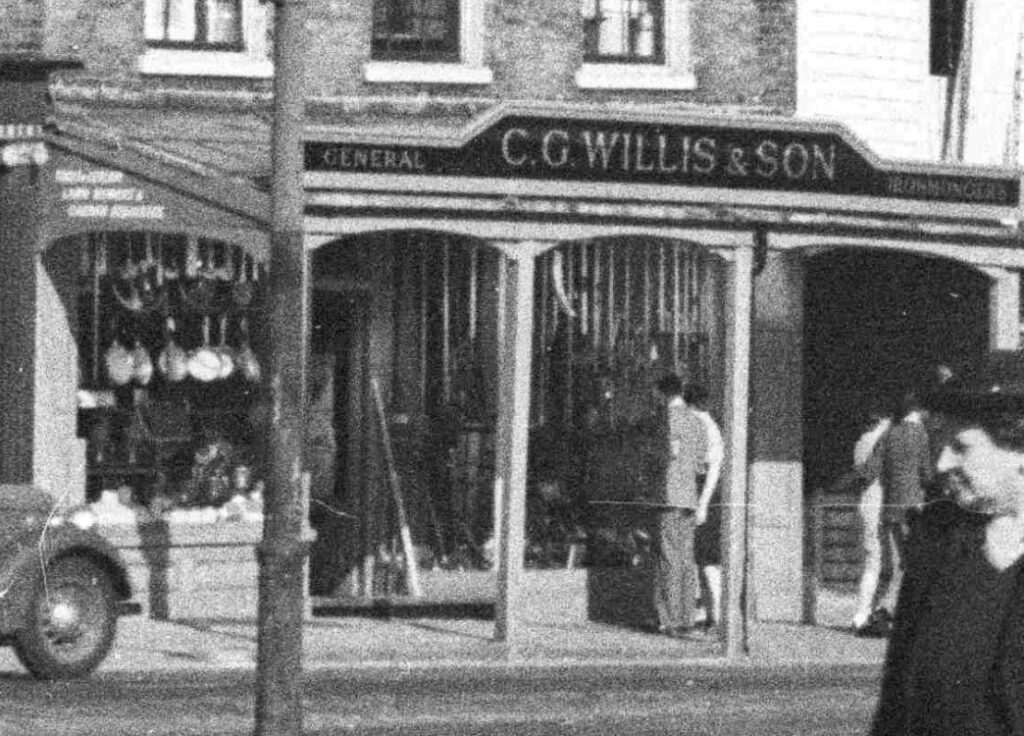

Back to my father’s 1948 photo, and I love enlarging, and looking at the detail of some of these photos. Looking across the street, we find C.G. Willis & Son, General Ironmongers who appear to have an array of pans hanging outside the shop. The shop is now a Cafe Nero:

To the right of the above shop, was Garden Layout Specialists, with a couple of small children in a pram parked outside:

Garden Layout Specialists was an interesting name, and presumably refers to some type of shop selling gardening supplies. The shop is now an estate agents.

As with the above two shops, the 611 trolleybus has disappeared from the streets of Highgate.

Bus route 271 was introduced to replace the 611 trolleybus. The 271 covered much of the same route, starting from Moorgate, and later being extended to Liverpool Street.

The 271 ran until a couple of months ago, when it was replaced by the 21 and 263 routes. These two existing routes were part diverted from their original route to cover for the closed 271. All part of TfL’s gradual reduction in the number of bus routes across the city.

So there are still buses running up and down Highgate Hill, however for some exercise, and a view of some interesting buildings, it is well worth a walk up Highgate Hill.

For more of my father’s photos of Highgate, see this post on Highgate’s pubs, history and architecture.