I will take any opportunity to view London from a high point, and just before last Christmas there was a tour of St Mary Islington, which included a climb up the tower to look at the view of London from the point where the tower meets the spire.

I could only make the late afternoon tour, however this provided a view of London after dark, which is always impressive. Hopefully I can return for a daytime tour, and if you are interested in the tour of this historic church, I have put a link at the end of the post to where I found out about these tours.

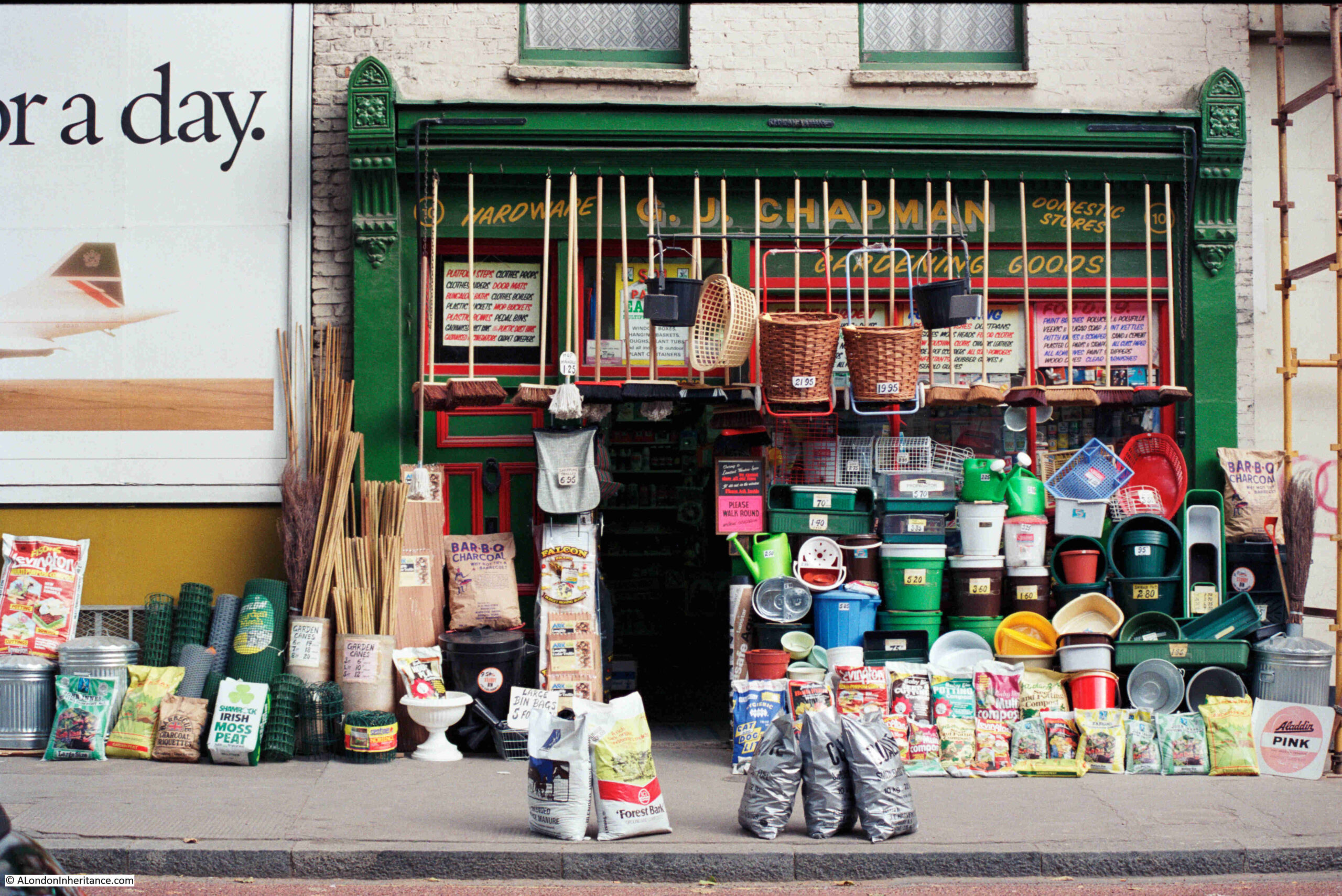

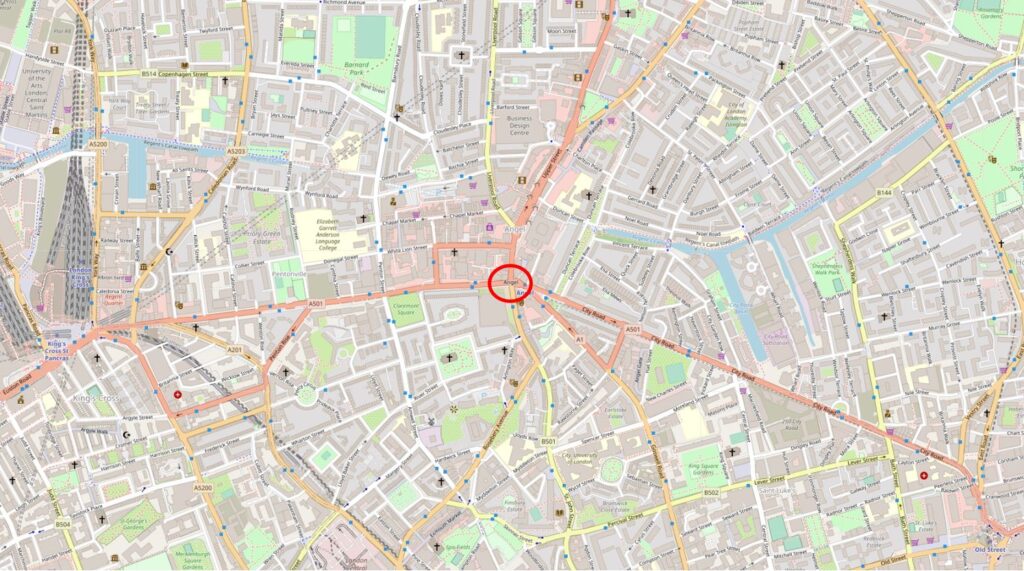

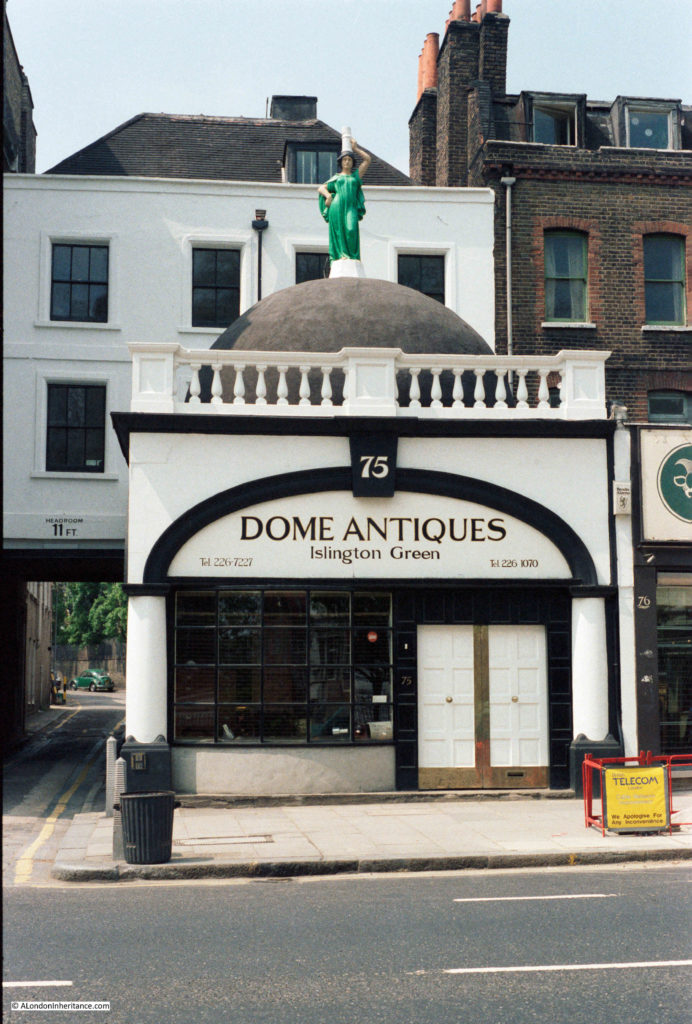

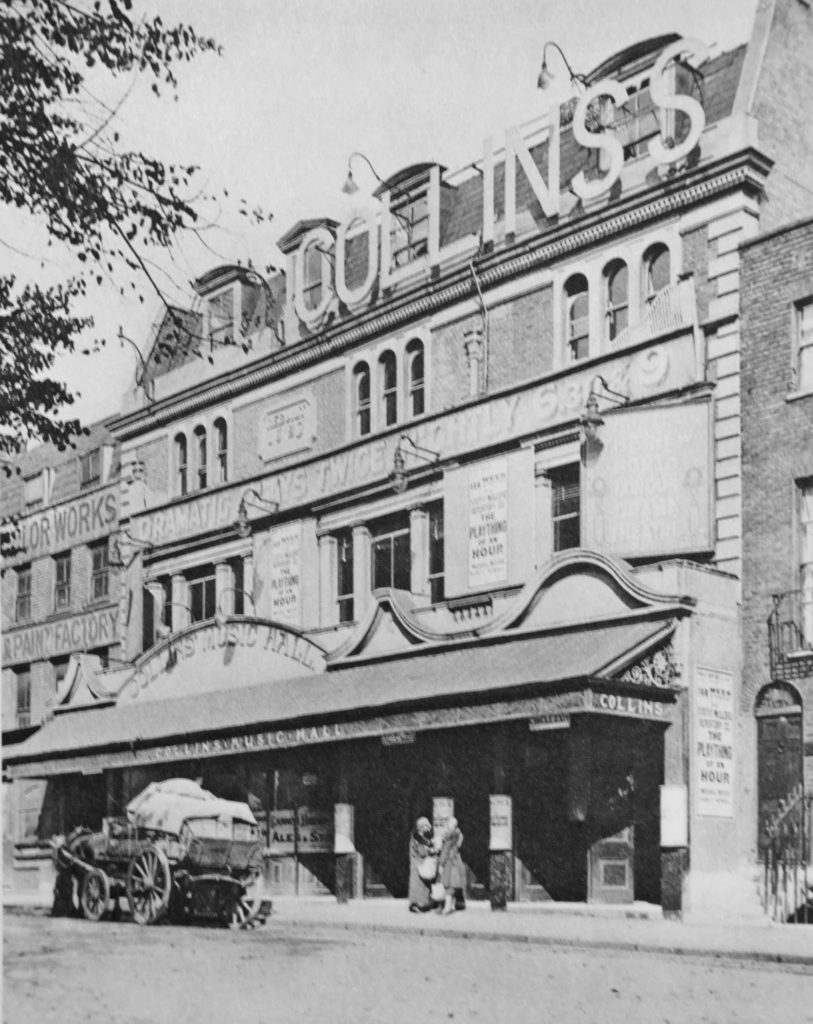

St Mary Islington is in Upper Street, and is a short walk from Angel underground station, continuing past Islington Green. As you walk along Upper Street, the spire of St Mary’s is a landmark on the right of the street:

Then the full front of the church comes into view, which is easier to see in winter when there are no leaves on the trees between church and street:

The church we see today dates from two distinct periods. The front façade of the church (except for the portico and columns), the tower and steeple date from the 18th century, however the body of church is from the mid 20th century.

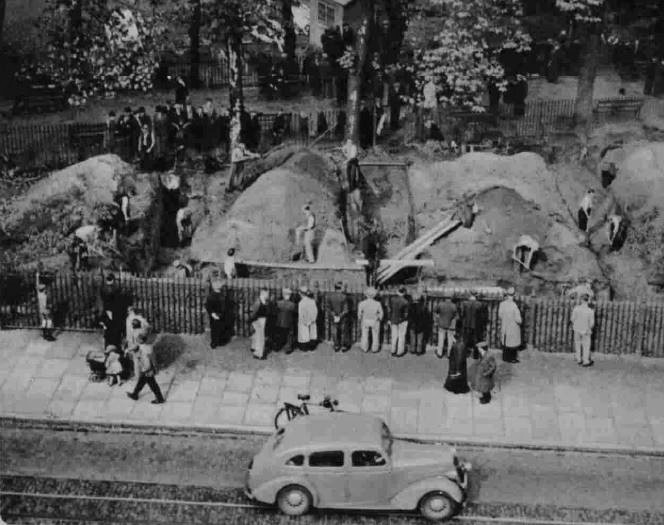

The church was bombed in September 1940 when a bomb landed on the nave, which suffered substantial damage. The tower and steeple survived. The church was rebuilt in the early 1950s to a design by the architectural partnership of Seely & Paget.

The new nave of the church was built on the same outline as the original, and walls lined with tall windows to allow a large amount of natural light into the nave of the church. From the churchyard we can see the new nave and the original tower and steeple:

As with the majority of London churchyards, St Mary’s has been cleared of gravestones and has been converted to a garden. The churchyard was closed to new burials by the 1852 Burial Act which applied to churches in the metropolitan London area. As with so many London churches, St Mary’s had been taking very many burials over the centuries, and with Islington’s rapidly growing population, it was impractical to continue to use the churchyard, even without the 1852 Act.

Thirty acres of land was purchased in East Finchley for the use of St Pancras and Islington for burials.

The gardens at the rear of the church on a sunny December afternoon:

Looking back towards Upper Street, with the church on the right, and as with many London churchyards, when they were converted to gardens the gravestones were moved to the edge and form parallel rows along the external wall:

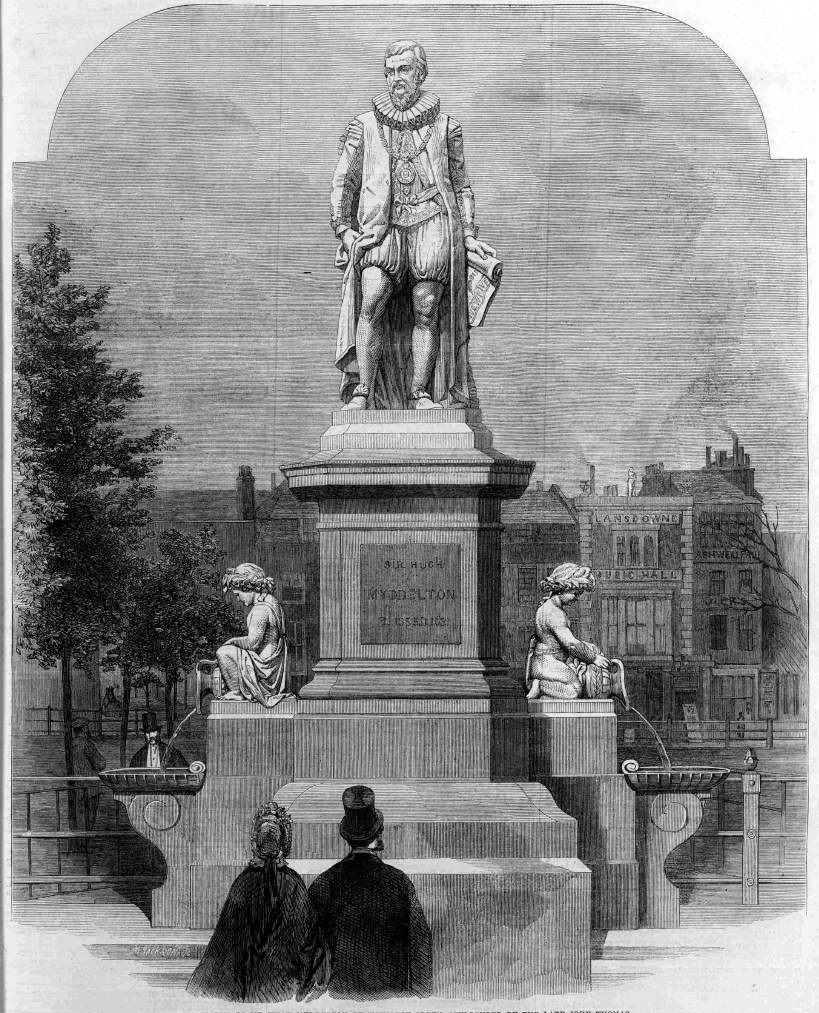

There is a named grave of a significant Islington resident next to the front of the church, just behind bus stop N on Upper Street. This is the grave of Richard Cloudesley:

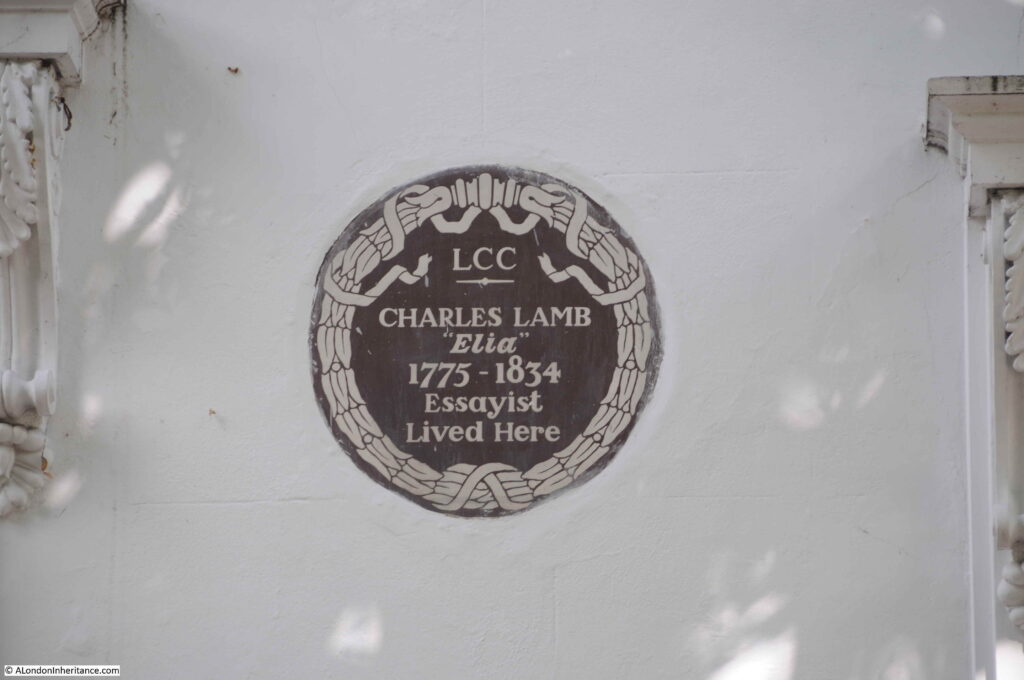

Richard Cloudesley was born around 1470 and died in 1517. He was an Islington resident and landowner. In his will he left two “stony fields” covering an area of around 14 acres, and these became part of a charitable trust which is still in existence and today is simply known as the Cloudesley.

The fields were rented out and generated an income, however with the northwards expansion of London during the early 19th century, the land was becoming valuable for house building, so in the 1830s, the trust began selling leases to parts of the lands, and what would become the Cloudesley Estate began to be built.

Whilst much of the land and houses have been sold, the Cloudesley charitable trust still owns around 100 properties, and the income from these continues to support the aims of the trust, which includes the health needs of Islington residents, along with a grants programme which helps maintain and repair Church of England churches in Islington.

The grave in the above photo is not where Richard Cloudesley was originally buried. His body was taken from an unknown location in the churchyard, and reburied in the current position in 1812. The grave was originally more ornate than we see today, however being so close to the church it suffered from bomb damage in 1940, and in 2017 the Cloudesley charity provided funding to repair and restore the grave.

The tower of the church supports a spire – the most visible feature in the surrounding streets:

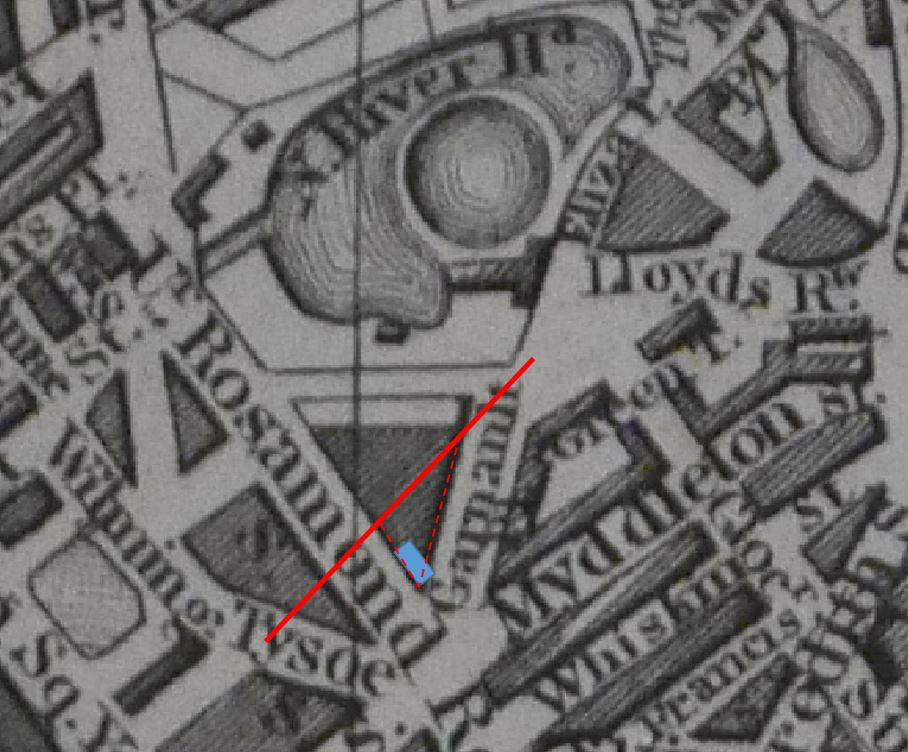

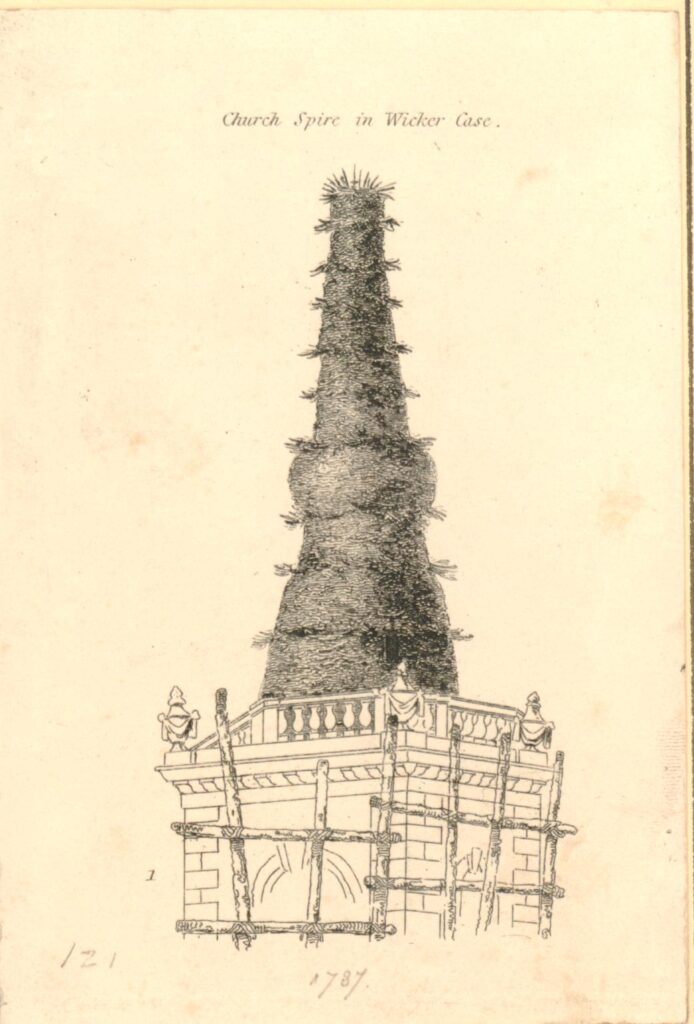

The spire has an interesting history, as in 1787, during repairs to the tower, it was decided to install a lightning conductor on the spire. Rather than construct scaffolding around the spire, the church contracted a basket maker by the name of Thomas Birch, who charged the church £20 to effectively build a wicker casing which fully enclosed the spire. Inside this wicker casing was a set of stairs that allowed workmen to reach the full height of the spire.

The spire, surrounded by its wicker case is shown in the following print from 1787 (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Although Thomas Birch was paid £20 by the church, he found another way of making more money and he advertised the spiral staircase as a means for the public to reach the top and see the view. Apparently charging for the climb and view raised a further £50.

What is not clear from the above print is where someone climbing the spire could have looked out through the wicker and see the view, whether they had to climb the full height and peer out over the top of the wicker, which would have been an experience not for those with a fear of heights.

The site of St Mary’s has been the site of a church for very many years.

It is in a key position. Upper Street has long been an important road from the City of London to the north, and the church is alongside this road.

There is very little evidence to confirm, however there may have been a church on the site in Anglo-Saxon times. Evidence for this seems to be mainly based on the parish of St Mary the Virgin being established in the year 628 by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

There was an 11th century church built on the site, and we were shown a stone with a zig-zag pattern in the crypt which apparently dates from the 12th century church.

The next church on the site was built in 1483, and this version of the church would last until the mid-18th century.

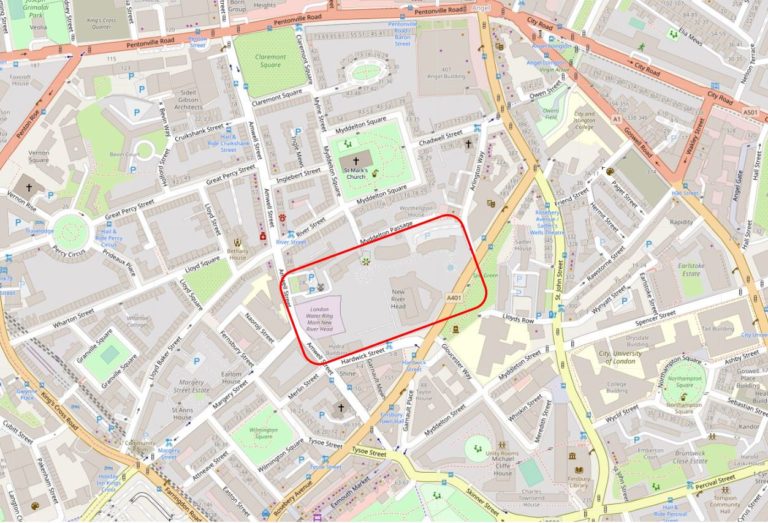

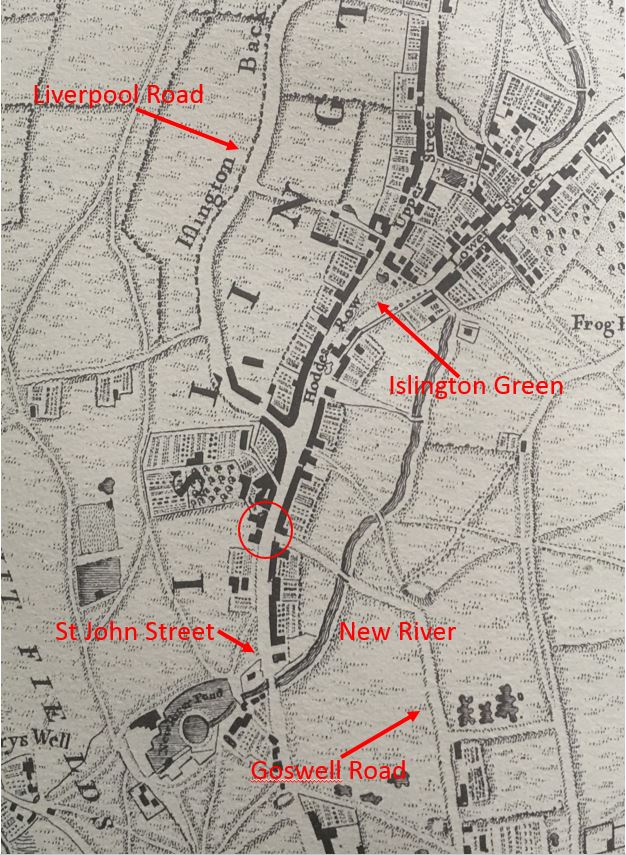

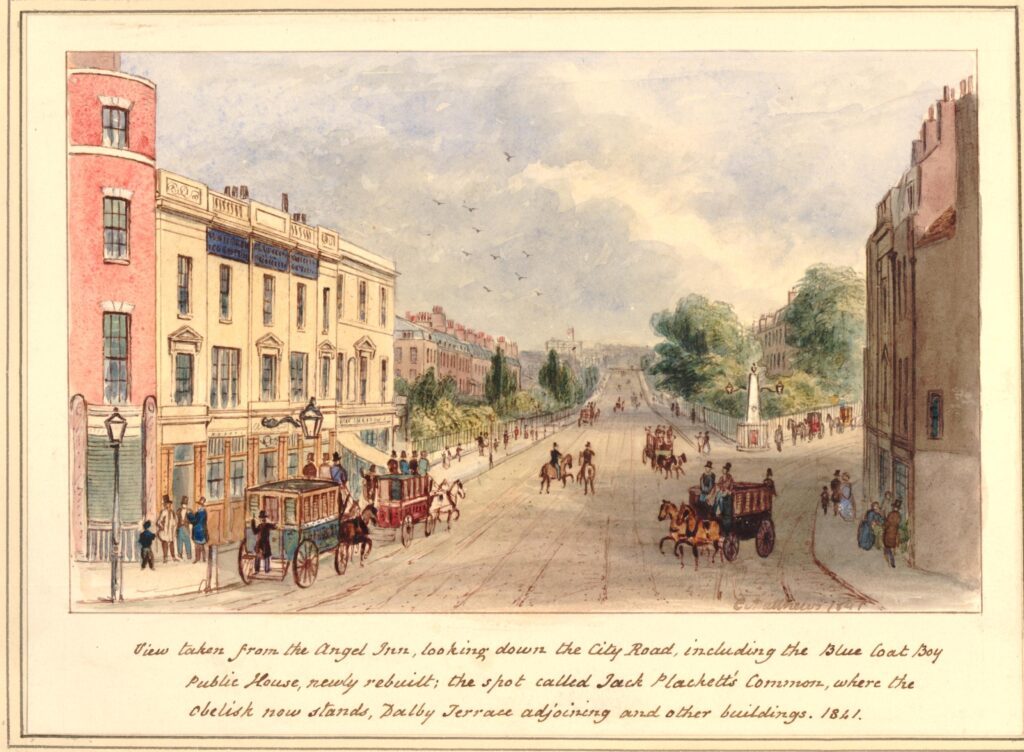

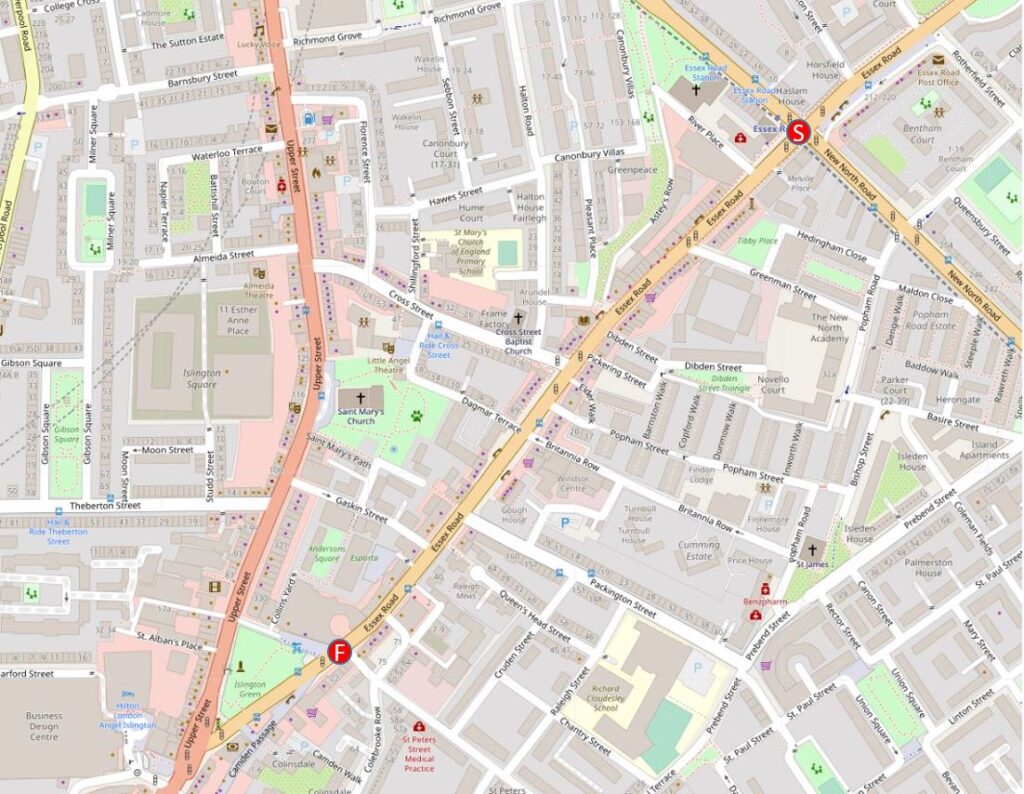

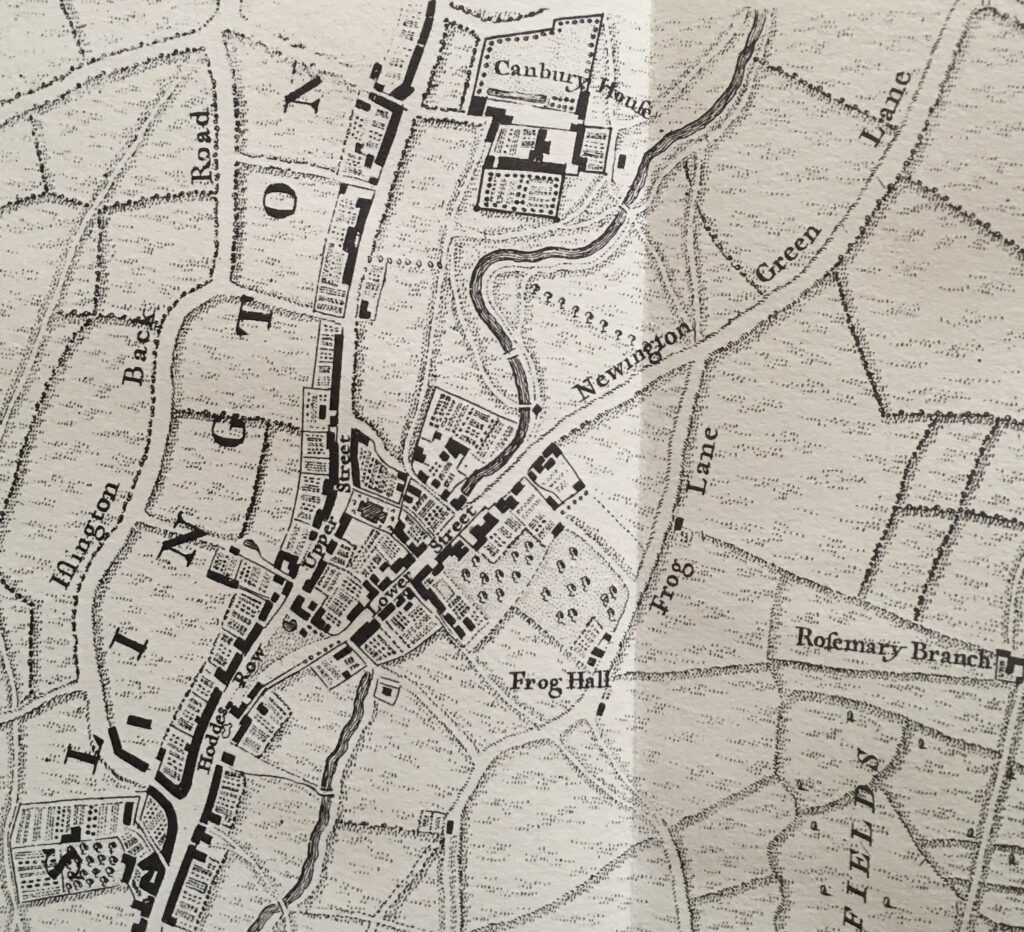

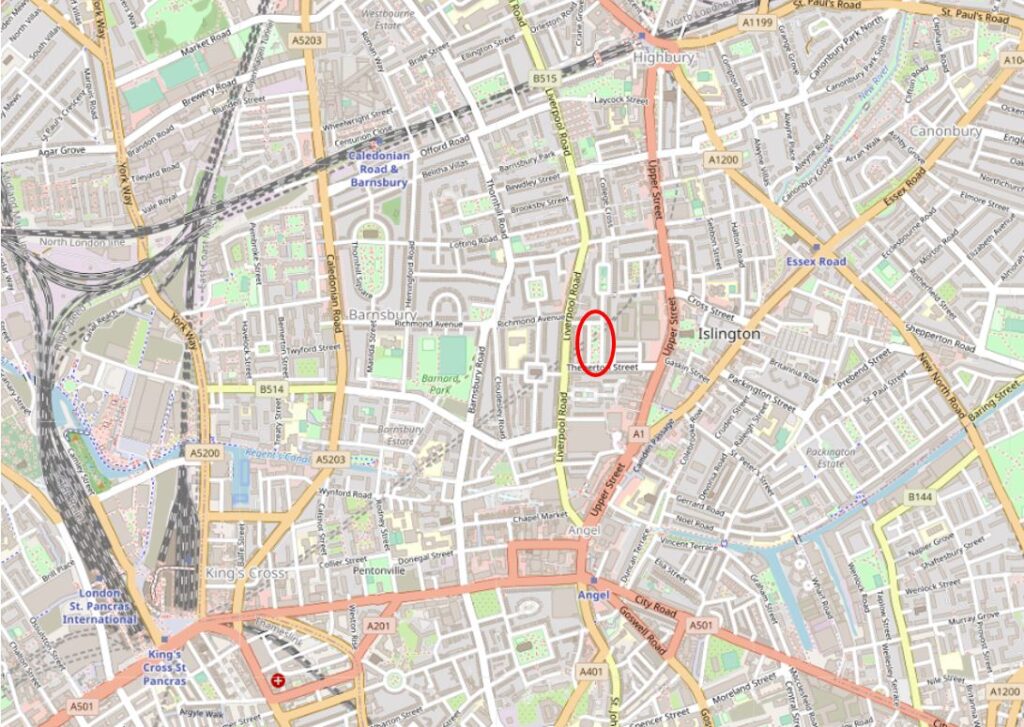

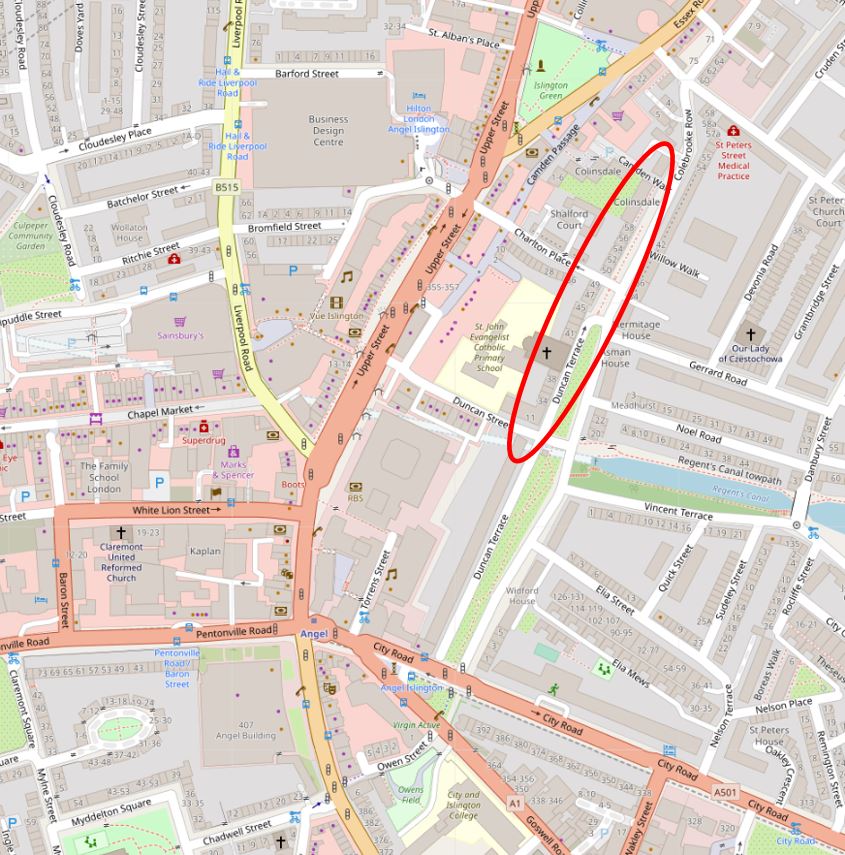

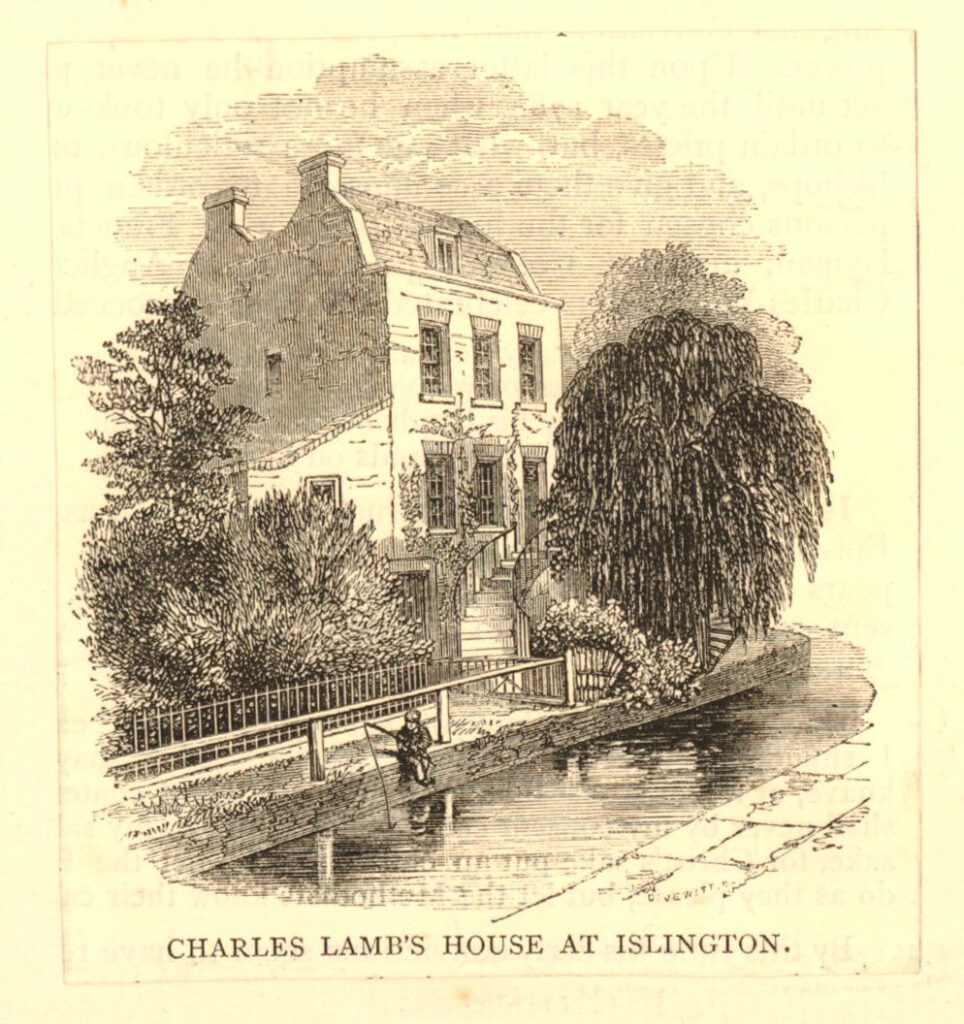

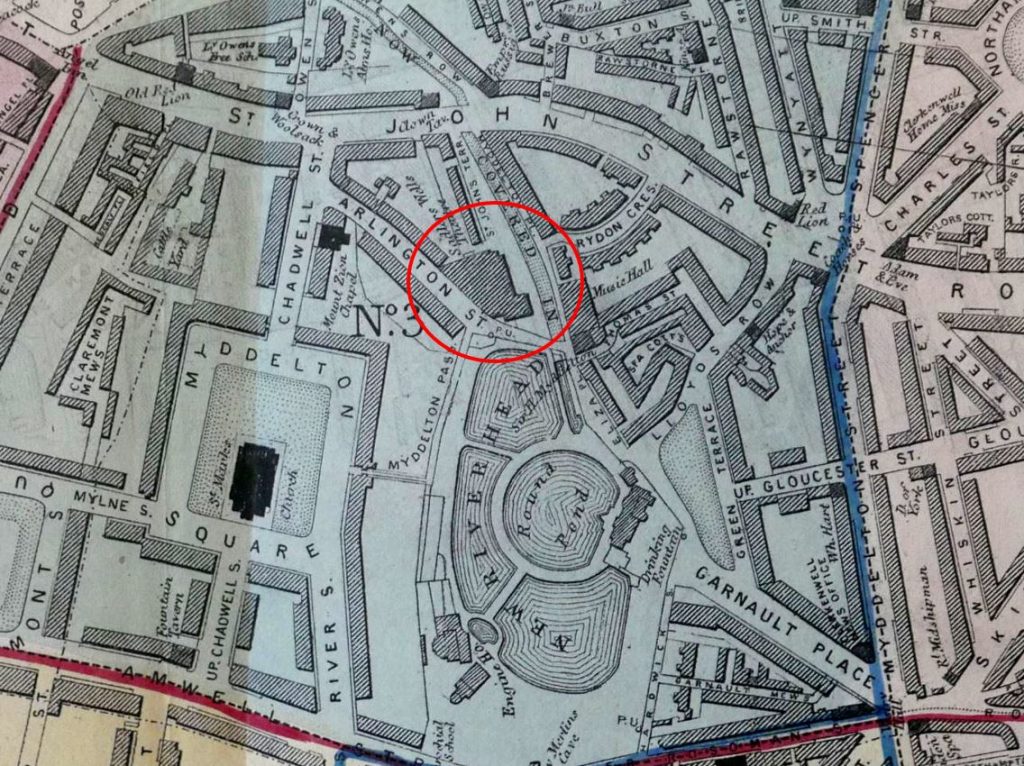

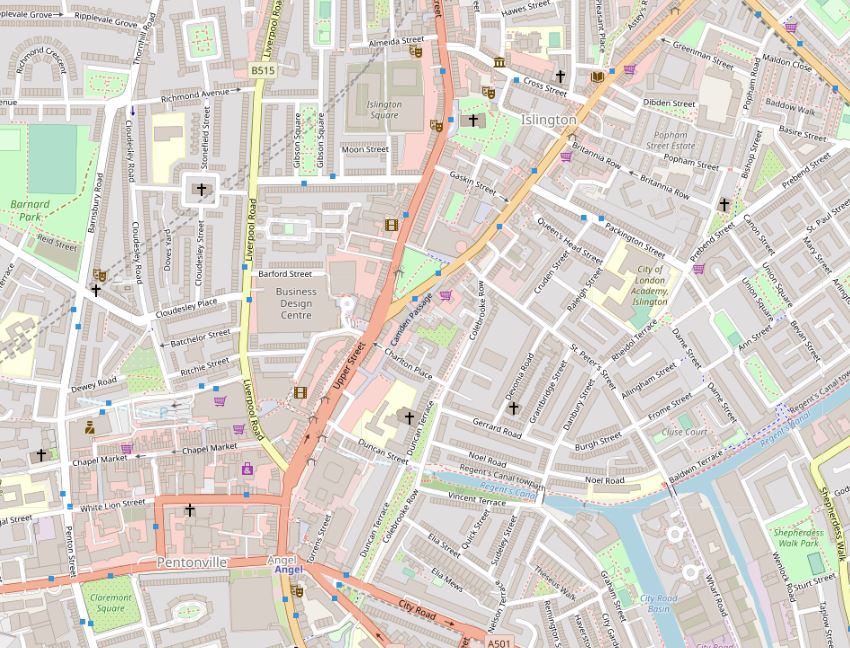

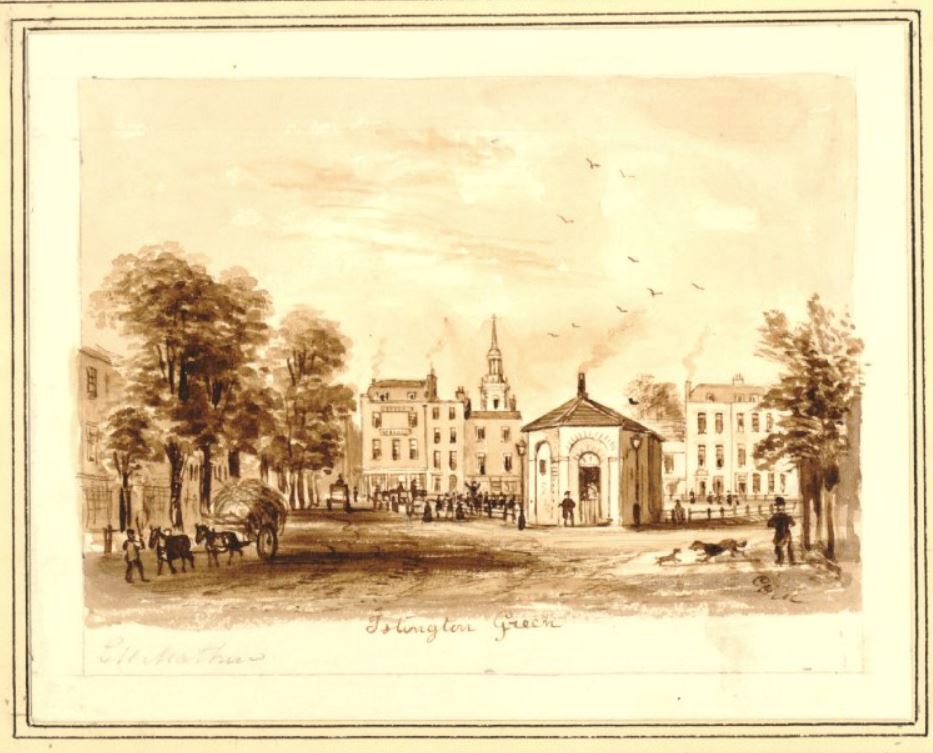

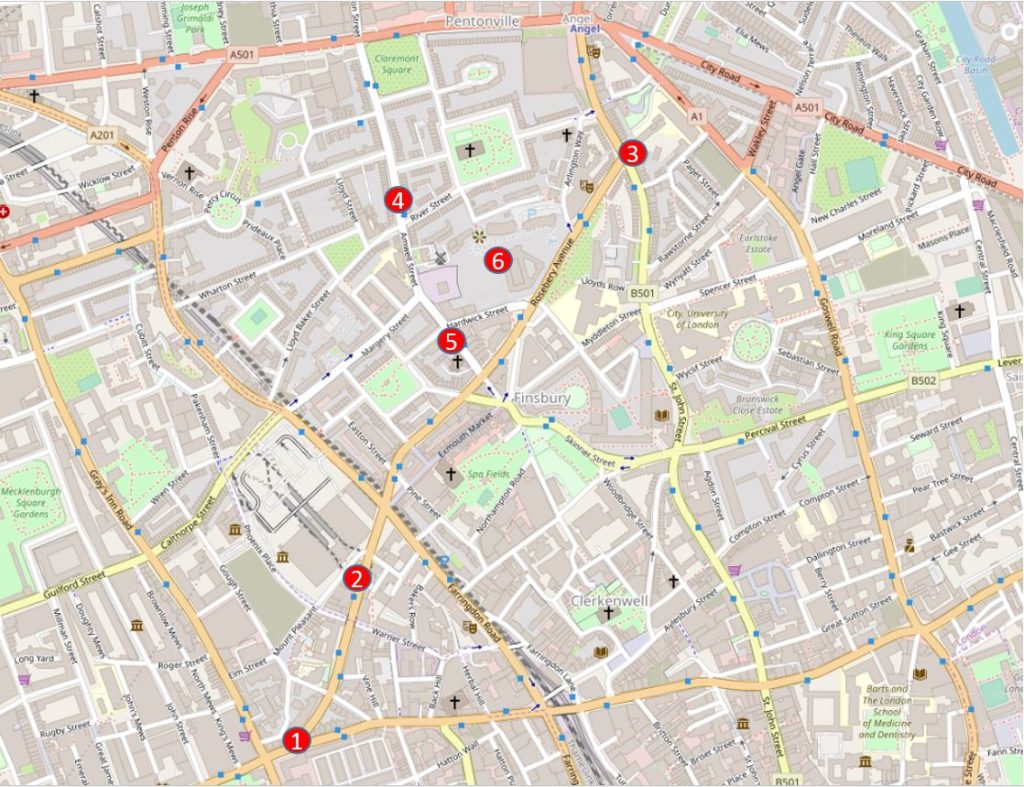

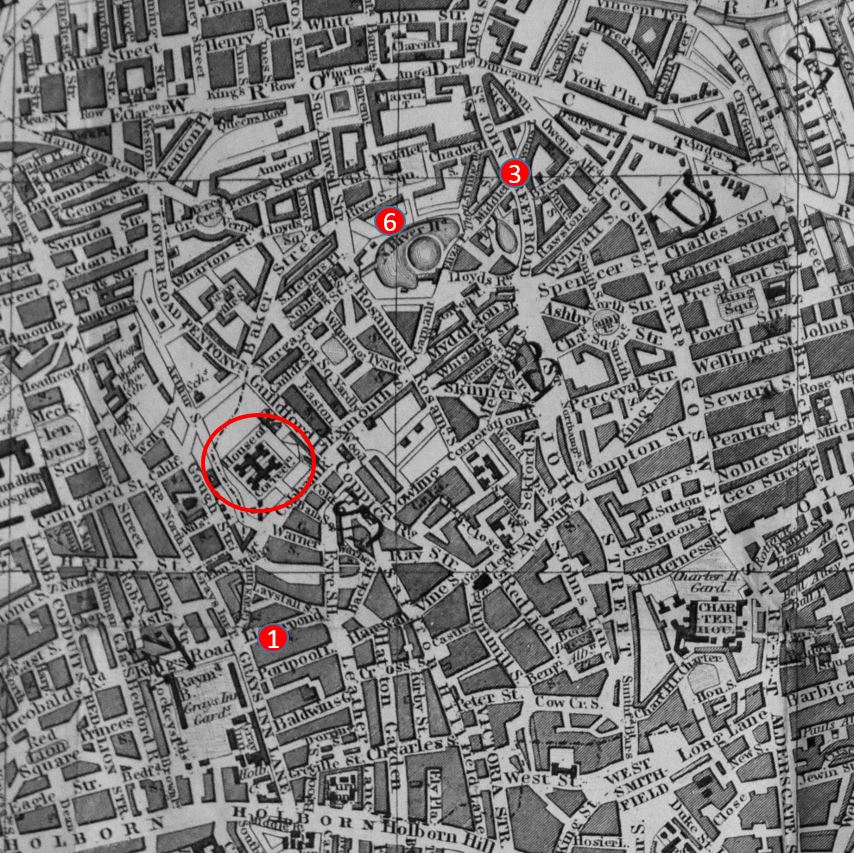

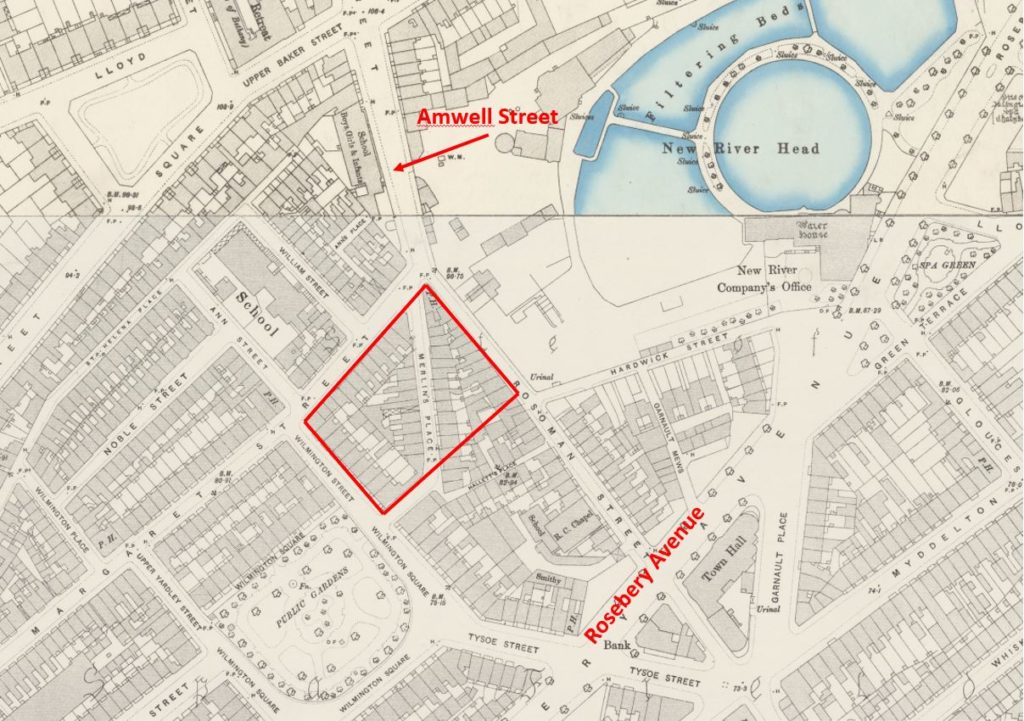

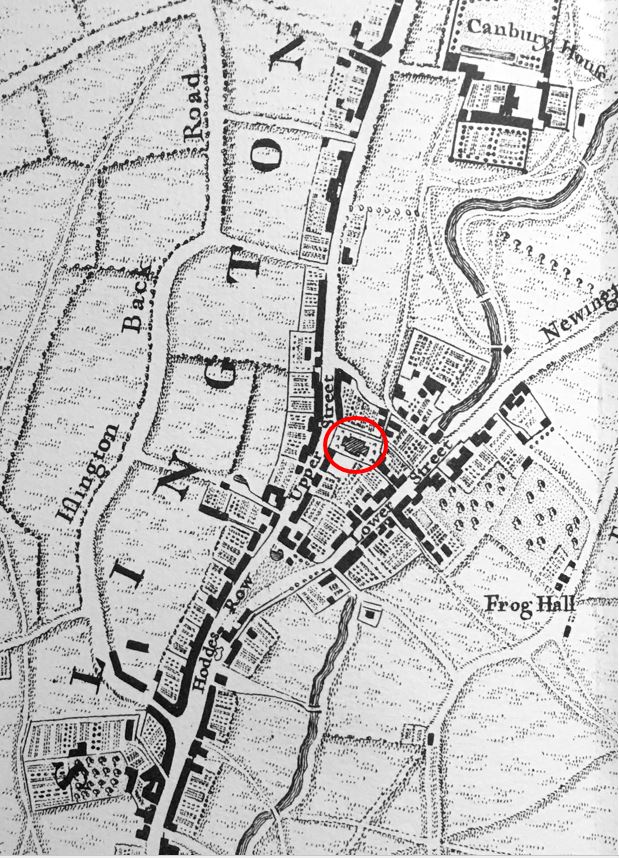

John Rocque’s map of 1746 shows the church (circled in the following extract), at a time when Islington was still mainly rural with buildings extending along Upper Street and Lower Street (now Essex Road), gardens, and the wider countryside being fields.

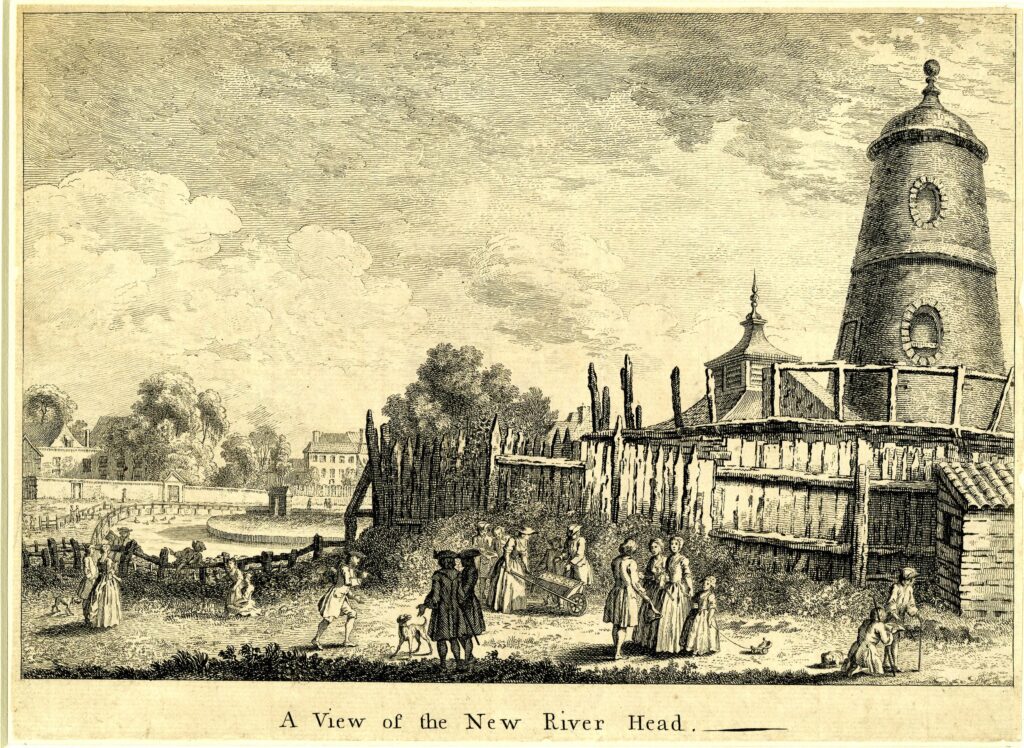

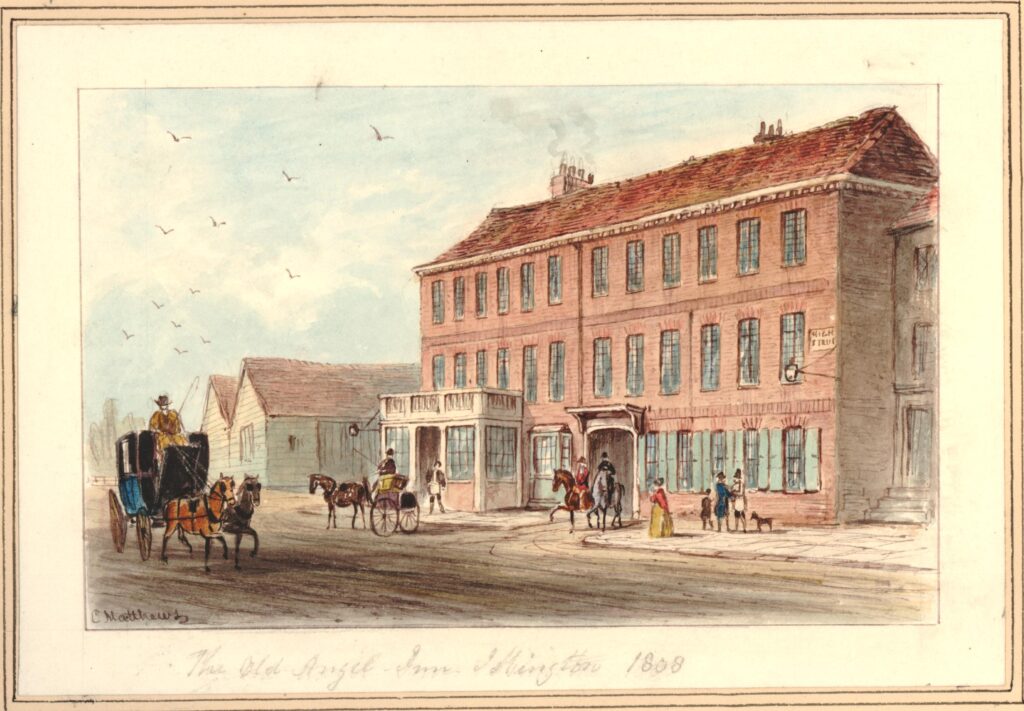

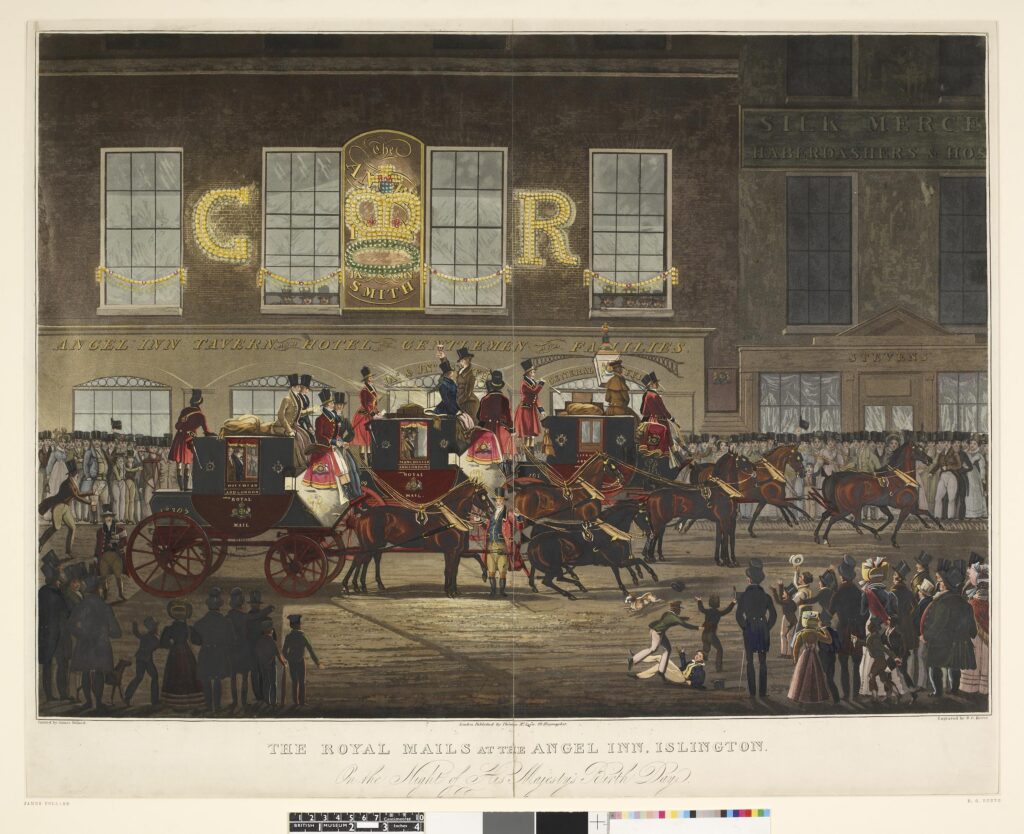

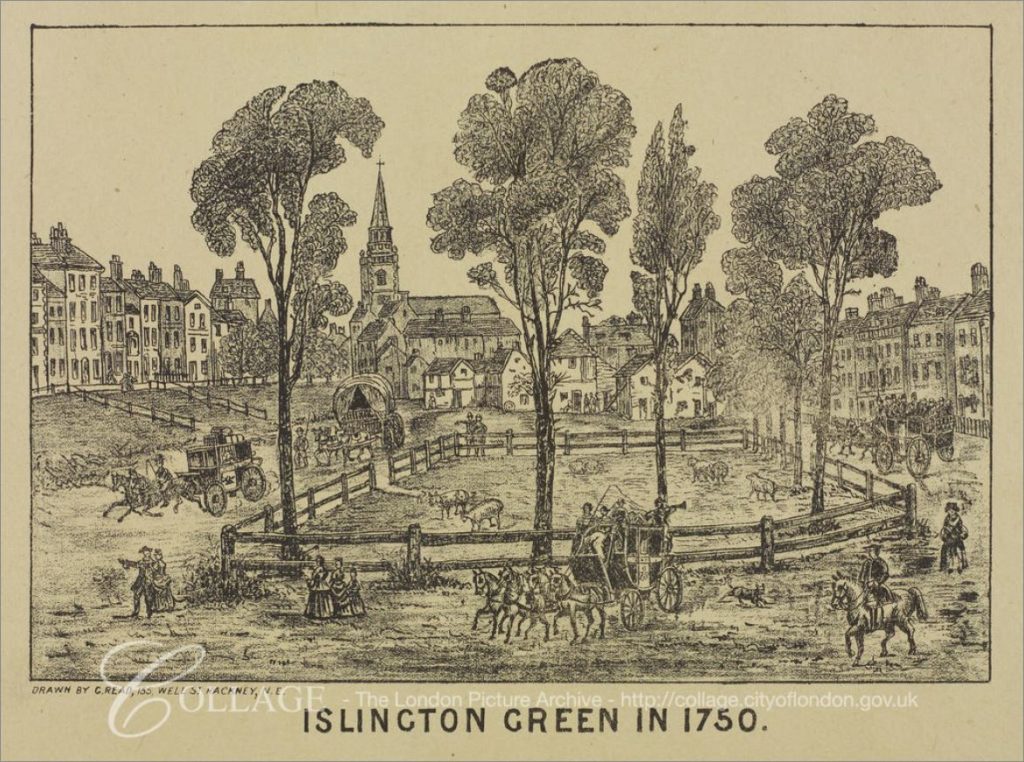

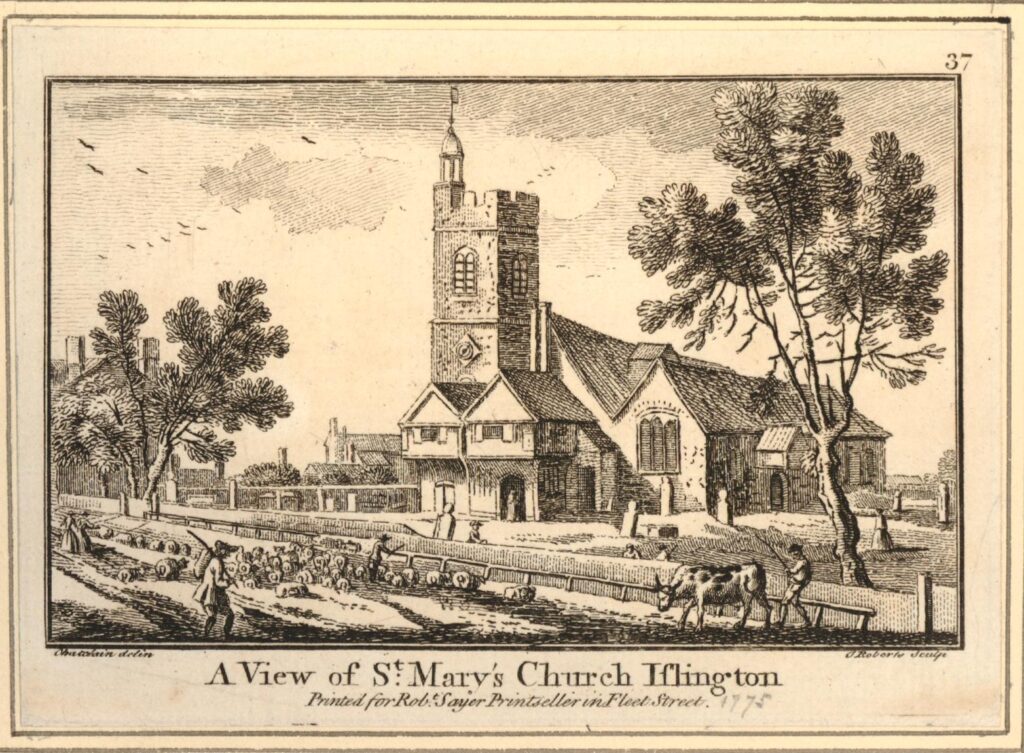

As well as Rocque’s map, the following print shows what the view of the church would have been at roughly the same time as Rocque’s map (although the print shows a date of 1775, the British Museum record states c. 1750) (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The view is looking across Upper Street towards the church, and shows a cow and sheep being herded along the street. Islington at the time was known as a place where cows were kept with their milk being sold in the City, and Upper Street was also used as a route to Smithfield Market.

There appear to be two houses attached to the west front of the church, facing Upper Street. It is not clear when these were built , or there original purpose, however around 1710 rooms in these buildings were used to provide a school.

If the 1750 date is correct, then the church in the above print is the 1483 version of the church. By 1750 it has fallen into a poor state of repair, and an Act of Parliament was approved to demolish and rebuild the church.

Funds for the new church were gathered by a tax on local land and property owners.

The tower in the above print looks reasonably substantial and this appears to have caused a problem when attempts were made to demolish the church. The first attempt to take down the tower was by the use of gunpowder, which did not work, so a large fire was built in the foundations of the tower, which apparently worked.

A new church was built by a Lancelot Dowbiggin. He was a joiner, and may have been local as he was later buried in the churchyard. This latest version of the church did not include the portico and the colonnades, which can be seen in the second photo in the post, and when viewed from a distance do look a bit as if they have been stuck onto an earlier church. These additions were made in 1902.

It was Dowbiggin’s church that survived until the bombing in September 1940, and his tower remains to this day.

The mid 18th century rebuild of the church included a new set of bells which were cast in the 1770s. These are still in use in the church and were renovated and rehung in 2003. The walk up the tower passed the entrance to where the bells are hung, unfortunately being dark, they could not be seen.

Time to have a look inside the church, but before I walked in, I noticed the following poster adjacent to the entrance to the church:

A lovely bit of graphic design, but the reason it really caught my eye was the similarity to the design on the spine of a series of books produced from the late 1940s to the early 1950s.

This was the County Books series, a wonderful set of detailed, illustrated descriptions of English Counties published by Robert Hale Limited of Bedford Square. Each book was written by an author who knew the area.

I have the six books covering London, along with books for a couple of surrounding counties, and the following shows the spine of the book on the left and the main cover on the right. As can be seen “The County Books” graphic at the top of the spine is the same as in the poster outside St Mary’s:

I cannot find out who designed the covers for the Robert Hales County Books, but they all have an identical cover design, with only the name of the county, the author and the picture changing from book to book.

Walking into the church, and we can see that this is not an old design, and how the large windows of Seely & Paget’s design let in a large amount of natural light, even on a late December afternoon. The following photo is looking from the entrance towards the altar:

The following photo is from near the altar looking back towards the entrance:

Due to the degree of bomb damage, there are very few original features to be seen in the church.

As well as the portico and colonnades built on the front of the church in 1902, the work also provided a new font for the church, and the original 18th century font was moved to the crypt, and it was this that saved the font in September 1940.

The 1902 font was destroyed and as part of the 1950s rebuilt of the church, the 18th century font was moved from the crypt, back up to the main church:

And the Arms of George III, which had been hung in St. Mary’s in 1781 were recovered from the ruins of the church, restored and returned to the new church:

My first visit to the church was during the early afternoon, during daylight, as the tour was late afternoon and after dark, so I left the church for a couple of hours then returned for the tour which took in the main body of the church and the crypt, before heading up the tower, the top of which was reached by a very narrow set of steps.

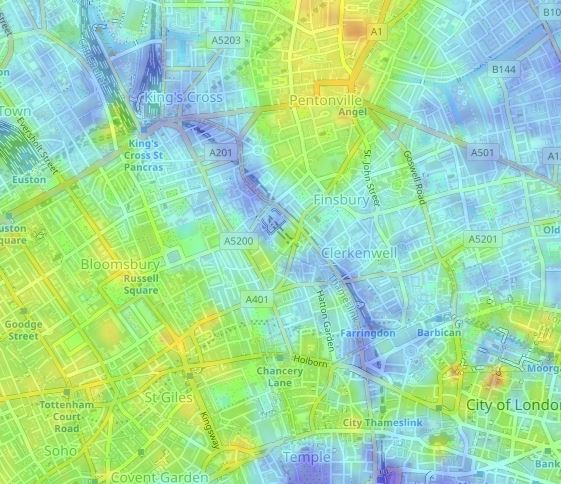

The view on reaching the top of the tower was well worth the climb. This is the view looking to the City of London on the right, with the Isle of Dogs and the towers surrounding Canary Wharf on the left:

I had set-up the camera with hopefully the right settings to take photos at night, at the top of a tower with a narrow walkway and a light breeze, whilst avoiding any camera shake, and for most of the photos this seems to have worked.

A close-up view looking towards the City of London, with the Shard to the right:

And zooming into Canary Wharf and surrounding buildings, showing how large parts of the Isle of Dogs is now covered in tall towers, brightly lit at night:

Looking towards the south and west, the purple light of the London Eye can be seen on the left edge of the photo, and towards the right is the BT Tower. Upper Street is the road, and to the right of centre is the long roof of the old Agricultural Hall:

The following photo is looking north, with Upper Street running up towards Highbury Corner. Just to the right of the far end of the street are the blue lights of the Union Chapel. I believe the yellow lights on the horizon are those of the Emirates Stadium.

A final look over towards the City, with one of the stone decorations on the top of the tower in the foreground:

The photos hopefully provide an impression of the view from the tower, however looking at the view from a narrow walkway at the top of the tower, with the spire disappearing into the darkness above certainly adds to the experience.

I understand that there may well be more tours in the future. They are led by Clerkenwell and Islington Guides, and I found out about the walks from their newsletter which can be subscribed to from the home page of their website, here.