A few weeks ago I published a post about the South Bank before the Festival Hall with some photos taken on the South Bank. This week I want to cover the same area, but this time showing the scene from the north bank of the Thames as this provides a very clear view of how a small area between Waterloo and Hungerford Bridges has changed.

The following photo was taken by my father from the north side of the Thames next to Hungerford Railway bridge in 1948:

Hungerford Railway Bridge is to the right and Waterloo Bridge is on the left hand side, both bridges framing the future site of the Royal Festival Hall. To the left of the photo is the Shot Tower and to the right is the Lion Brewery.

Until the 16th Century, this area was foreshore to the Thames, overgrown with rushes and willows and subject to flooding at high tides. The road behind the Royal Festival Hall, Belvedere Road was the Narrow Wall, a road built on the embankment to the Thames.

From Old and New London (Edward Walford (1878)): The spot between the Belvedere Road and the river between Waterloo and Westminster Bridges – till recently known as Pedlar’s Acre – was called in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Church Osiers from the large osier-bed which occupied the spot (an Osier is a type of Willow) This is a plot of land of some historical notoriety. It was originally a small strip of land one acre and nine poles in extent , situated alongside the Narrow Wall and has belonged to the parish of Lambeth from time immemorial. It is said to have been given by a grateful pedlar. (There is also a story that the pedlar’s dog discovered treasure there whilst scratching around in the ground). On Pedlar’s Acre at one time was a public house with the sign of the pedlar and his dog and on one of the windows in the tap-room the following lines were written:

“Happy the pedlar whose portrait we view,

Since his dog was so faithful and fortunate too;

He at once made him wealthy, and guarded his door,

Secured him from robbers, relieved him when poor.

Then drink to his memory, and wish fate may send,

Such a dog to protect you, enrich and befriend”

What ever the truth of this story, it is still fun whilst walking round the Royal Festival Hall to imagine the Pedlar and his dog digging in the willow beds and finding treasure.

Continuing from Old and New London:

Not far from the southern end of Waterloo Bridge on the site now occupied by the timber-wharfs of Belvedere Road and close by the Lion Brewery, which abuts upon the river stood formerly a noted place of public resort known as Cuper’s Gardens. As far back as the eighteenth century if not earlier it was famous for its displays of fireworks.

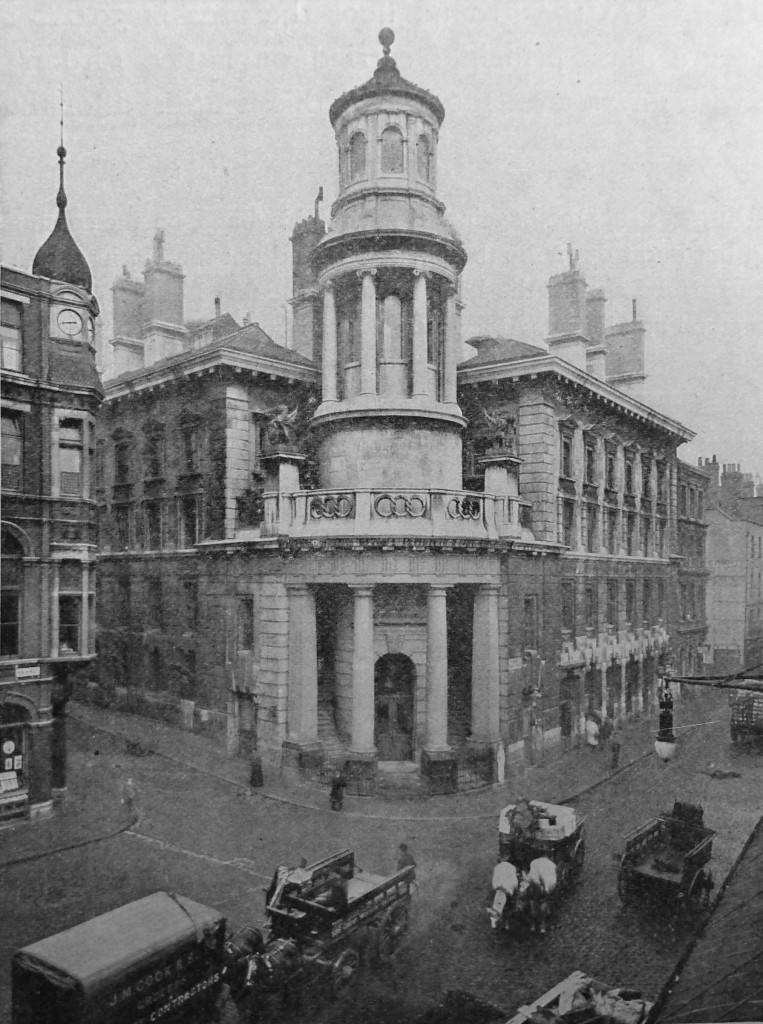

The Shot Tower was built in 1826 as part of the lead works on the site for the production of lead shot. The tower is built of brick, with a diameter at the base of 30 feet. The tower tapers slightly so at the top gallery the diameter is 20 feet. The gallery is 163 feet from ground level.

From the gallery, molten lead was dropped to form large shot, half way down the tower was a floor where molten lead could be dropped to make smaller shot.

The Lion Brewery is on the site of a former Water Works where water was taken from the river for distribution to the local area. Pumping water from the river was replaced by a supply from reservoirs on Brixton Hill and the works were removed in 1853. The site then became a brewery which became the Lion Brewery Company Limited in 1866. The building was damaged by fire in 1931, it was then used for a short time for storage and then remained derelict until demolition in 1949 to make way for the construction of the Royal Festival Hall.

The following photo was taken from the same position a few years later during the construction of the Royal Festival Hall in 1950 (judging from the position of the shadow on the river this was taken at the same time as the 1948 photo, some careful planning to get the comparison right). Construction was fast, from the foundation stone being laid by Clement Atlee in 1949 to the hall being opened on the 3rd May 1951

The Shot Tower remains (apart from the gallery at the top) and would remain for the duration of the Festival of Britain. The core of the Royal Festival Hall is under construction, covered in scaffolding and cranes. The new river frontage is also under construction.

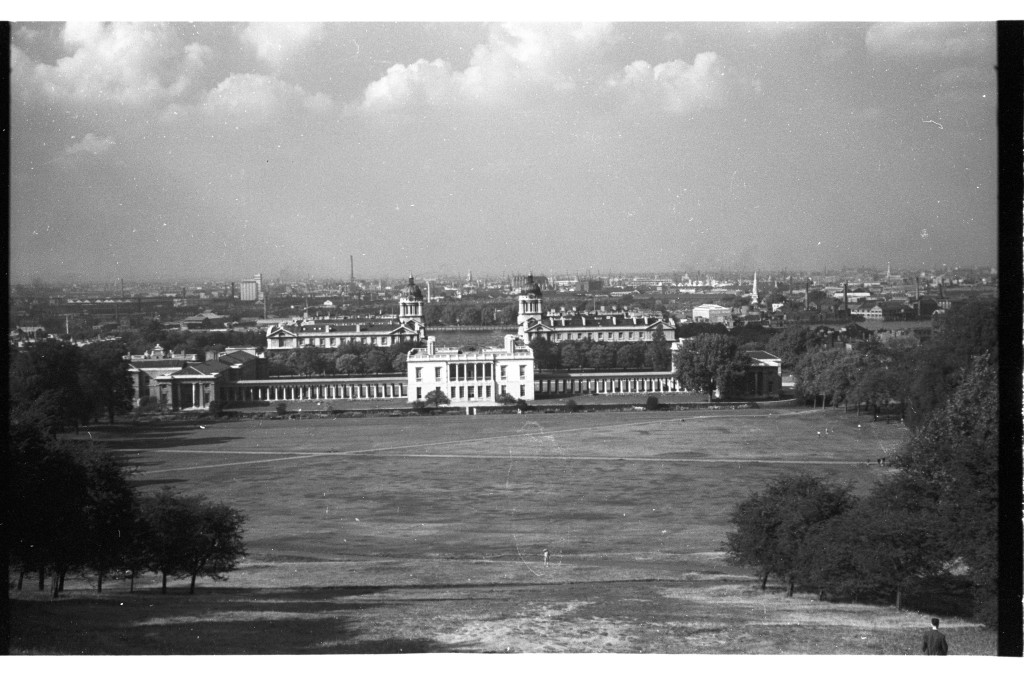

The Royal Festival Hall was constructed by the London County Council and was planned as the one permanent building to remain from the overall Festival of Britain site that occupied the South Bank.

The following is my 2014 photo of the same area. I could not get into exactly the same position as my father when he took the original photos as the new foot bridge extends further into the river from the railway bridge.

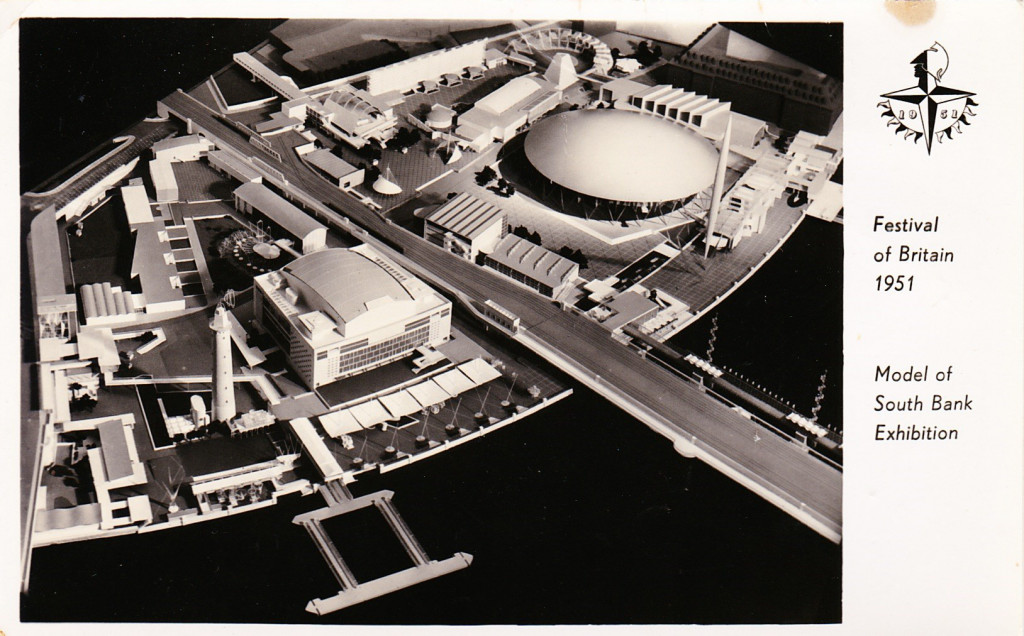

The following Festival of Britain postcard shows a model of the site with the Royal Festival Hall on the left of Hungerford Railway Bridge. Difficult to see from this model, but Belvedere Road runs behind the Royal Festival Hall, under the railway bridge and behind the Dome of Discovery on the right. It is incredible how this small area changed in a few years either side of 1950.

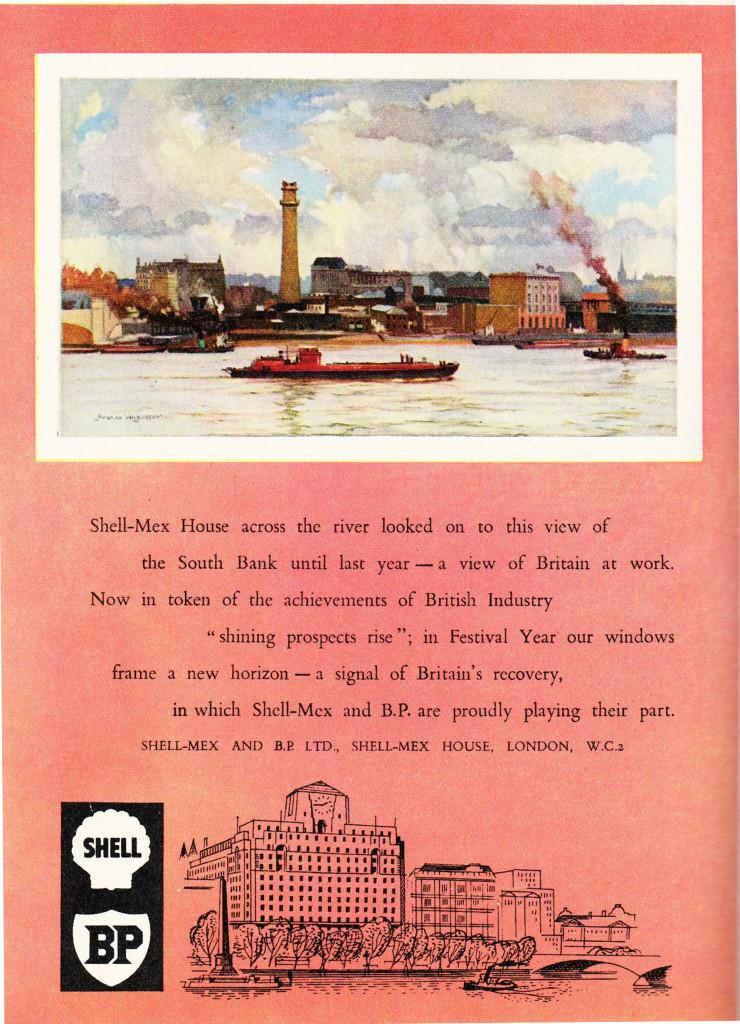

On the north bank of the Thames opposite the Royal Festival Hall is Shell Mex House. The following is a painting of the view from Shell Mex House included in the programme for the Festival of Britain. The Shot Tower and Lion Brewery with Waterloo Station in the background.

The text below the picture is typical of the mood surrounding the Festival of Britain, the prospect of a bright future following the long years of war. The Royal Festival Hall is the only remaining building from the Festival of Britain as the rest was quickly removed after the closure of the festival.

Photo focussing on the area around the Shot Tower:

And again showing the Shot Tower and river:

You may also like to read my earlier post covering the site of the Royal Festival Hall and the area towards Waterloo Station before construction started which can be found here.