All my walks have sold out, however I have had a request to run the “South Bank – Marsh, Industry, Culture and the Festival of Britain” walk on a weekday, so have added a walk on Thursday, the 9th of November, which can be booked here.

In 1952 my father was in Peterborough. It was one of the cycling trips he did with friends after National Service. Cycling and staying in Youth Hostels was a very popular means for young people to explore the country. It was cheap, much quieter roads ensured that cycling was safer and more enjoyable than it would be today, and for those who had been born, and grown up in London, it provided an ideal opportunity to see the rest of the country.

Although it was probably not realised at the time, it was also a time to see much of the country before the coming decades brought significant change. For example, when my father visited Peterborough, the population was around 54,000 and today it is well over 200,000. The city centre would also have a large new shopping centre, the Queensgate, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, which resulted in the loss and demolition of part of the historic street network.

Peterborough also has a connection with many of the buildings in London, as the city is the home of the London Brick Company, the name of the company dating from 1900 following the purchase of a local brick company by John Cathles Hill, who developed large parts of suburban London, using bricks from the Fletton deposit of lower Oxford Clays found around Peterborough.

I am going to start my tour of Peterborough, in the old market place, with a view from 1952 of the Guildhall:

The Guildhall dates from 1671 and has an open space at ground level for the market, and assembly rooms on the first floor, which were also used for meetings of the local council.

The Guildhall is at the eastern end of the Market Place and faces the entrance to the cathedral Minster Close.

It was obvioulsy not market day when the above photo was taken, as cars were parked under the framework for the market stalls.

Also, to the left of the Guildhall, you can see a building up close to the rear of the Guildhall, and to illustrate the scene today, I took a wider view to show how this has changed:

The Guildhall is still there and looks as it did in 1952. As shown in the 1952 photo, there were buildings up close to the rear of the structure between the Guildhall and the parish church of St. John. These have now been demolished. The market has also been moved to a dedicated market building and Market Square is now named as Cathedral Square.

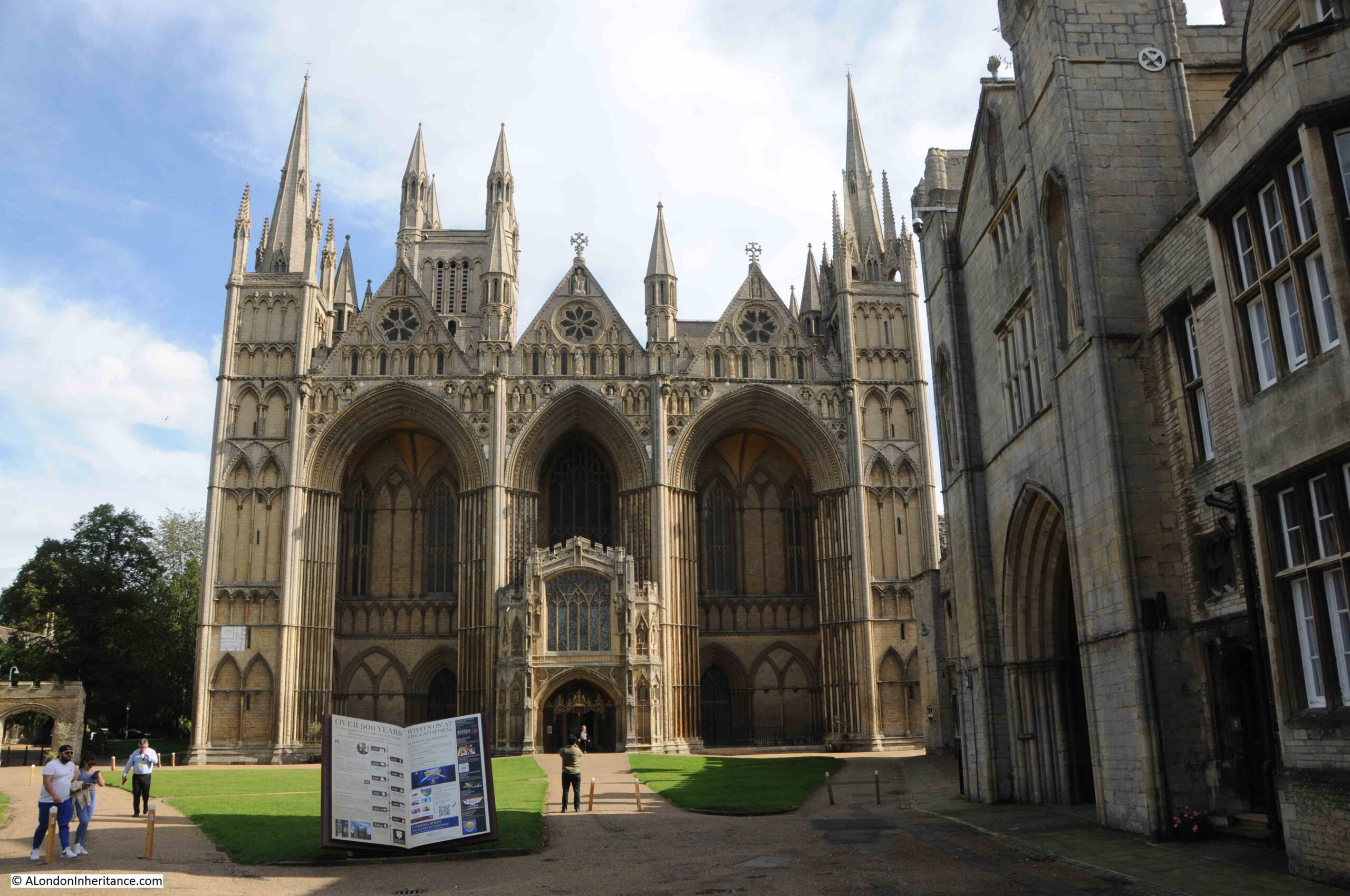

The cathedral is at the opposite end of Cathedral Square, and is reached through a gateway into Minister Close where the western front of the cathedral can be found, here photographed in 1952:

The cathedral today. The open book features key dates in the history of the cathedral:

Gateway into the area where the Deanery is located:

Seventy-one years later:

Peterborough is a Cathedral City, and the cathedral has been at the heart of the city for very many centuries.

Long before the current cathedral, a monastery was founded in 655 at what was then called Medeshamstede, on the edge of the Fens, a large area of eastern England, with much of the land being waterlogged or marsh. The site of the monastery was on dry land overlooking the Fens, and was an ideal location as the Fens provided supplies of fish, wildfowl, and reeds for thatching.

Viking raids across eastern England resulted in the deaths of all the monks in the monastery in 870, and the Christian church was wiped out as a functioning organisation.

The monastery was refounded just over 100 years later in 972 by King Edgar and Aethelwold, Bishop of Winchester, and the community needed to service the monastery, and that formed the start of Peterborough, began to grow around the cathedral.

In the year 1116, the monastery buildings, and much of the early town was destroyed in a fire which was believed to have started in a bakery (a parallel with the Great Fire of London), and the loss of the monastery buildings resulted in the construction of the building we see today, which commenced in 1118.

The need for funds to help with the construction of the new building led the monks of the monastery to create the market to the west of the cathedral, and the development of streets to attract commercial activity.

The monastic church would take decades to construct, and was finally consecrated in 1238, with additions and modifications continuing to be made during the following centuries.

In 1539 the monastery and abbey church were closed by King Henry VIII, who also confiscated the land and buildings.

Two years later in 1541, the church was reopened as Peterborough Cathedral, with the foundation charter for the cathedral being established on the 4th of September, 1541.

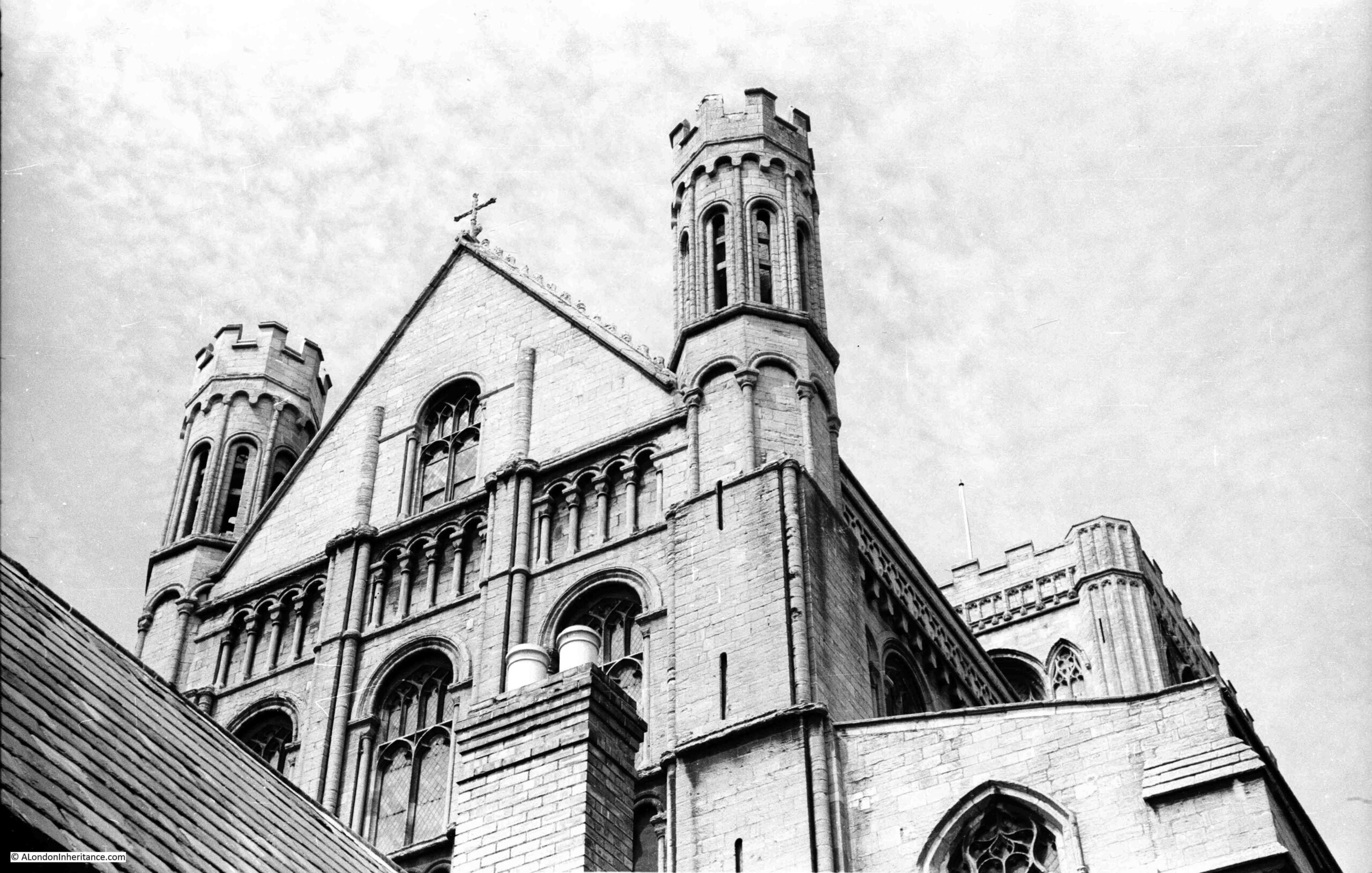

Time for a walk around the cathedral in 1952:

I could not easily take the same views as the two photos above, due to trees which have since grown around the cathedral and obscure some of the views.

However I could recreate the above photo:

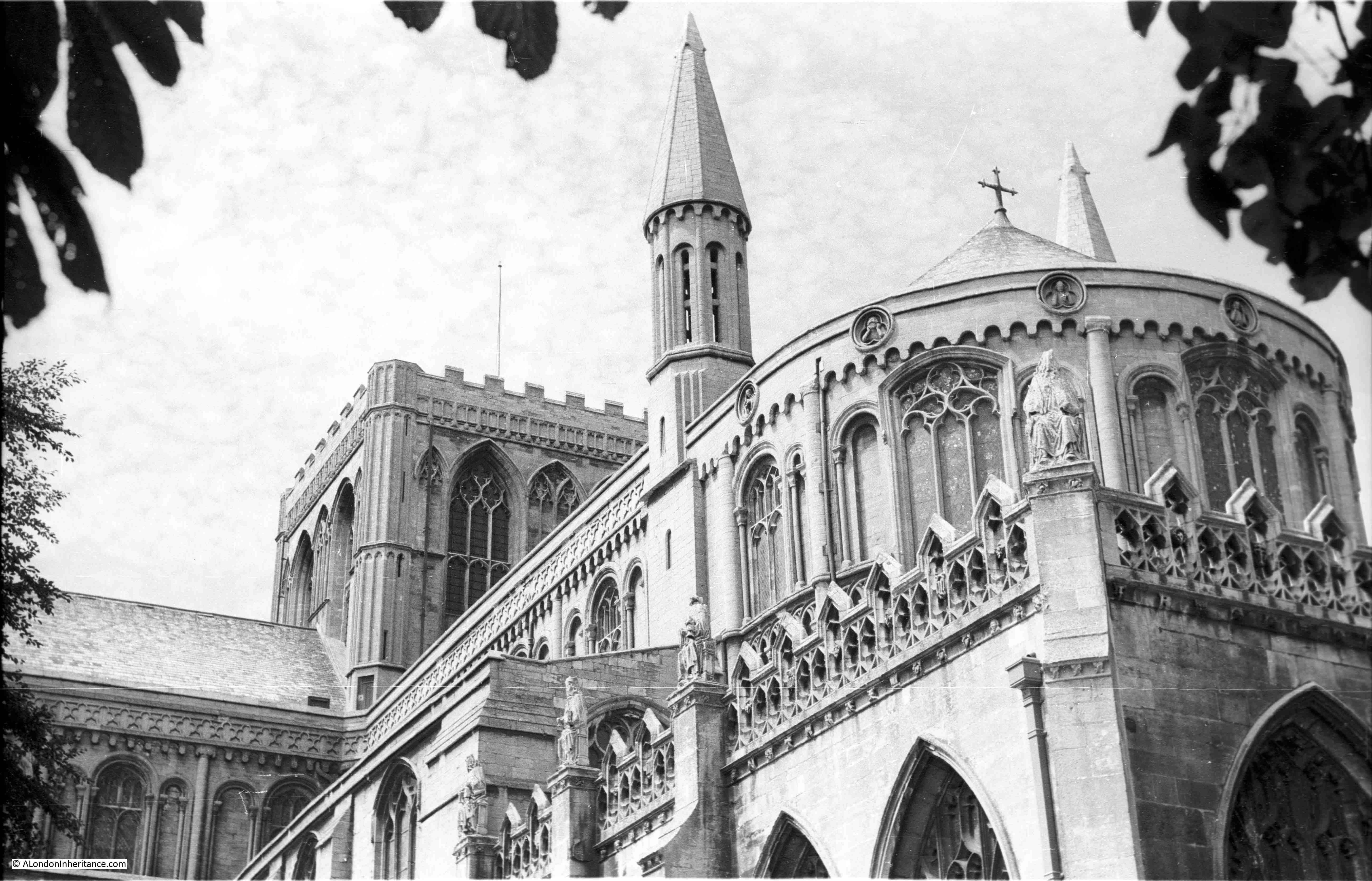

The eastern end of the cathedral is the subject of the following photo. The section in the lower right of the photo is known as the New Building and dates from a programme of building work carried out between 1496 and 1509.

The view today is almost identical:

When I can get these Then and Now photos as closely aligned as possible, given the very different cameras in use, and the view has hardly changed in 70 years, it is always a moment to stop and think just how many people have seen the same view over the centuries, and how many will do so in the future.

Buildings such as the cathedral, and the Guildhall in the Market Place, anchor the city’s history and provide a physical link with the past. Whilst shopping centres, office blocks etc. will come and go, these buildings are so much more than their physical appearance.

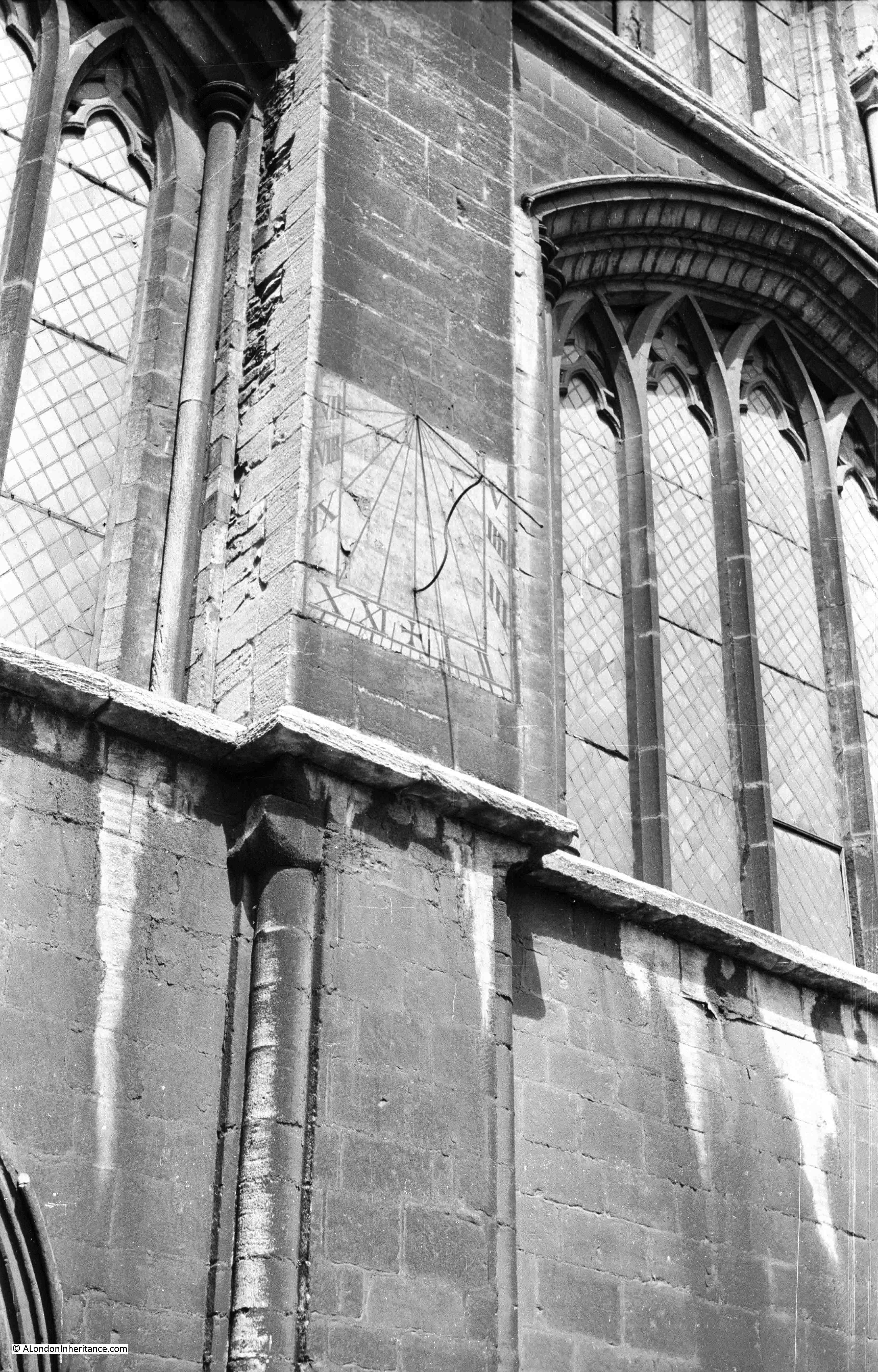

Painted sun dial:

I found a couple of sundials on the cathedral. One of the west facing front of the building and one of the south, however they were not in the same position as the above 1952 photo. I did find the sundial in the following photo on the southern side of the cathedral, which would be the correct location for such a device.

The grounds around the cathedral have long been used as a place of burial. On the southern side are a number of medieval stone coffins which were discovered during 19th century restoration works, and could be 12th century when the area was being used as a graveyard for the abbey community:

I could not find the location of the following photo:

I did ask one of the guides in the cathedral, who thought is was probably in the Cloisters, which were closed at the time of my visit due to tiles falling from the roof in recent winds.

The plaque in the above photo reads “The Monks Lavatory as renewed in the 14th Century”.

Peering through the gate to the Cloisters:

The view from the western front of the cathedral, looking back to the entrance gate which leads into the old Market Place where the Guildhall is located:

As could be expected, the interior of Peterborough Cathedral is magnificent. The view looking toward the altar:

The following photo is looking west along the Nave. Whilst the Nave is a wonderful example of 12th century architecture, the key feature of this part of the cathedral is the 13th century painted wood ceiling:

Although is has been painted a few times in the last 800 years, the wooden structure, style and carving is original, and makes the ceiling a unique example of such a ceiling within England, and indeed is one of only four wooden ceilings of this period surviving across the whole of Europe.

Peterborough was bombed during the last war, and the cathedral had a narrow escape from incendiary bombs, which would have devastated the wooden ceiling. As with St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, a team of fire watchers protected the cathedral in Peterborough.

As can be seen from outside, the cathedral has a relatively short central tower.

Many medieval cathedrals did have much higher towers and steeples, however the weight of these was often too much for the supporting structure and foundations, or often were badly damaged by high winds

The original 12th century tower was much higher. Just a couple of hundred years later in the 14th century, the tower was lowered due to stability problems.

Over the following five hundred years, the weight of the tower continued to cause stability problems and by the mid 19th century there were wide cracks developing in the pillars supporting the tower.

This required urgent work, and the tower was dismantled and rebuilt, and whilst not that dramatic a structure from outside, looking up at the tower from inside the cathedral we can get a wonderful view of the supporting pillars, the tower, windows (the tower is in the form of a Lantern Tower), and the decorated ceilings:

The ornately carved wooden pulpit dates from restoration works in the cathedral during the 1880s:

Cathedrals take on a different atmousphere at different times of the year, and in different weathers.

September sunshine brought plenty of light into the building, and every so often, on the stone floor, on medieval pillars, an array of coloured light filtered through the stained glass windows:

The original burial place of Mary Queen of Scots was in Peterborough Cathedral.

Mary was only 6 days old when she inherited the throne of Scotland after the death of her father, James V. For much of her early life Scotland was governed by Regents, and Mary lived in France and raised as a Catholic as she was seen to be at risk from the English.

Even after returning to Scotland and taking the throne, governing a mainly Protestant country did not go well. She was imprisoned and forced to abdicate. Mary fled to England, hoping to get protection from Elizabeth I, however Mary was also considered a legitimate claimant to the English throne, so Elisabeth had her imprisoned in a number of different places across the country.

After over 18 years of imprisonment, Mary was found guilty of attempting to assassinate Elizabeth, and beheaded in 1587 at Fotheringhey Castle in Northamptonshire.

She was buried in Peterborough Cathedral a few months later in 1587, and remained in Peterborough until 1612, when her son who was now James I arranged for her body to be reburied in Westminster Abbey.

The location of her burial in Peterborough Cathedral is still marked:

Peterborough Cathedral suffered badly during the English Civil War when the Parliamentary soldiers under Oliver Cromwell entered the town.

The cathedral was ransacked, and everything that could be associated with the old Catholic faith was destroyed. The cathedral’s library was also destroyed with the exception of a single book, the story being told at the cathedral that a clergyman persuaded an illiterate solider that it was a bible and should not be burnt.

Parts of the cathedral still show the damage from the Civil War, including the remains of a family monument shown in the photo below:

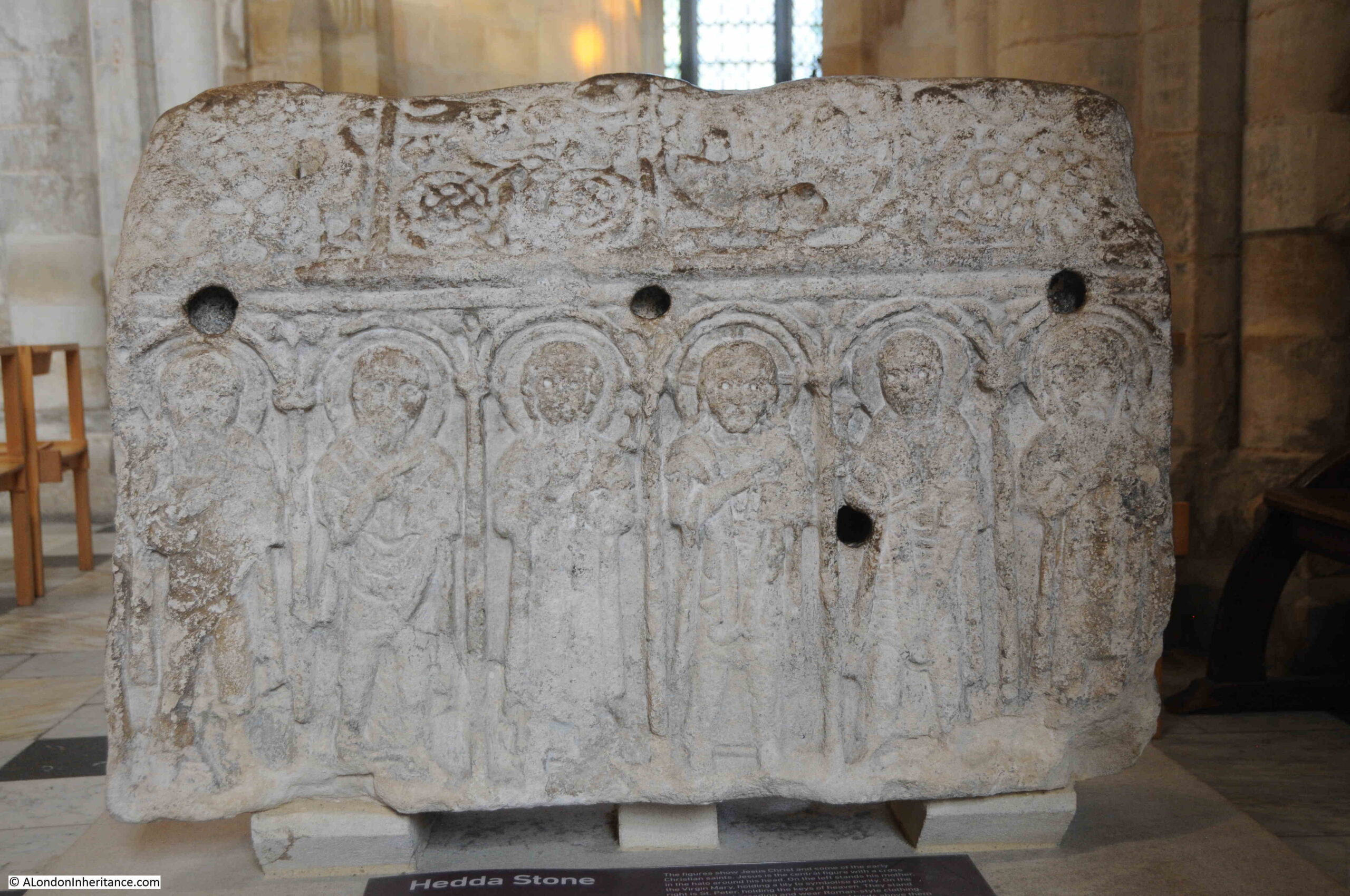

There is nothing visible of the early monastery built on the site of the present cathedral, however there is a single stone on display. This is the Hedda Stone and dates from around the year 800, and may have marked the grave of an Anglo-Saxon saint or king:

The stone is solid, so would not have held any relics or bones, and may have been part of a larger feature. It does provide an indication of the degree of decoration that may have featured in an early 9th century monastary.

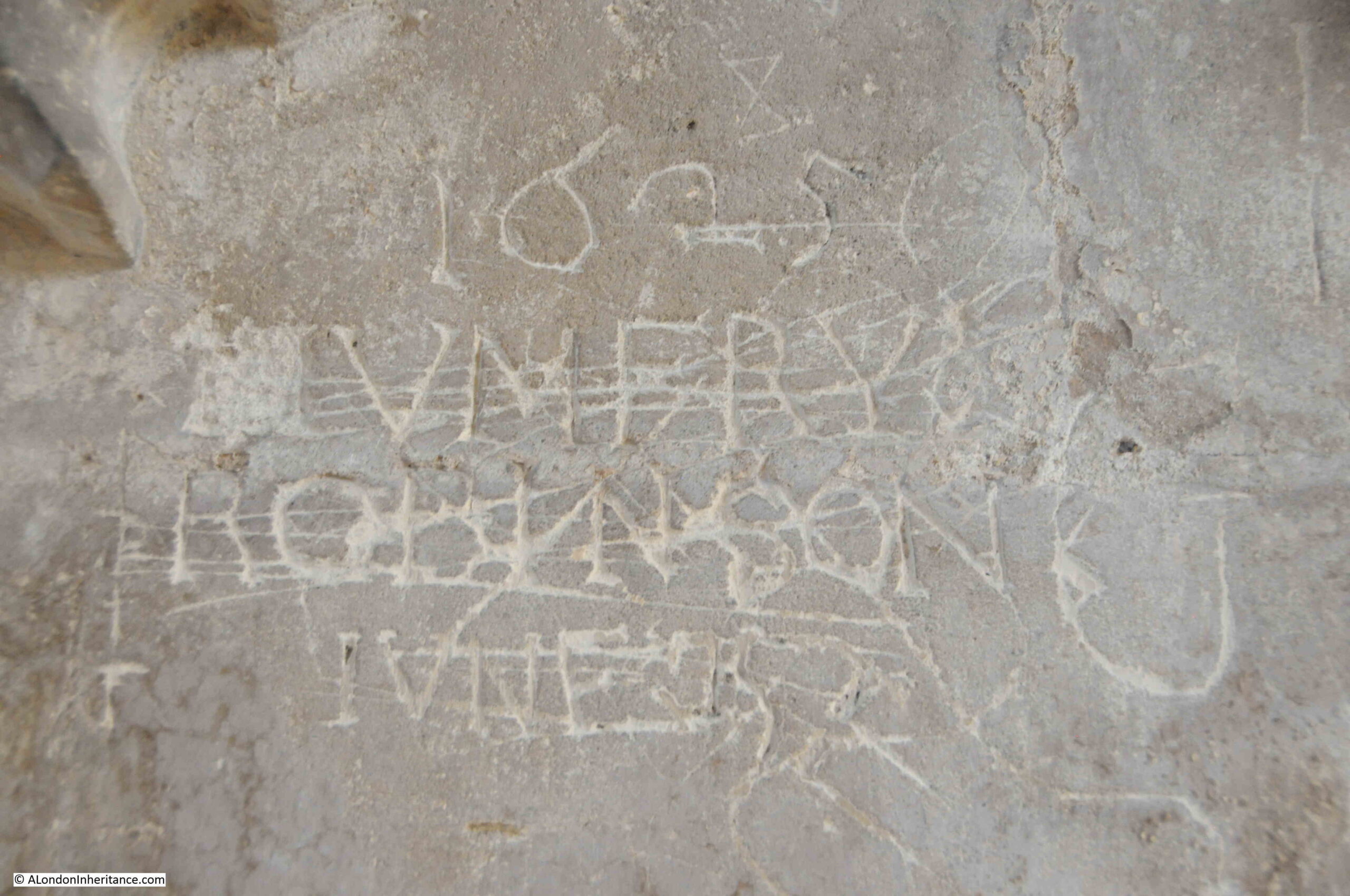

As with many cathedrals, many of those who have passed through the building in previous centuries have left their mark:

Between 1496 and 1509 there was an extensive programme of work across the cathedral, and the eastern end of the building saw an extension, which is still known as the “New Building”, which is rather impressive for a building that is 500 years old.

Perhaps the most impressive part of the New Building is the fine fan vaulting of the roof, which can be seen in the following photo:

Peterborough Cathedral is where Henry VIII’s first wife, Katherine of Aragon was buried. Her tomb was destroyed during the Civil War, however her body was undisturbed and the grave is now marked by a marble slab and memorials to Katherine.

Katherine of Aragon was born in 1485 to King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabel of Castile. At the age of 16 she was married to Henry’s older brother Arthur, however after his death at a young age, his younger brother Henry was in line for the throne, and Katherine’s future looked uncertain.

Her future looked secure when she married Henry when he became King in 1509. She ruled when Henry was aboard, usually fighting in France, and must have been a formidable woman as she governed when a Scottish army was defeated at the Battle of Floden.

It was Katheryn’s apparent inability to provide Henry with a son that led to her downfall. Henry VIII was desperate for a son and heir, and whilst married to Katherine, his eye was already on Anne Boleyn.

Without the Pope’s approval, he could not divorce Katherine, so this led to the separation of the Church in England from the Church in Rome. Henry divorced, married Anne Boleyn, and Katherine was sent to stay in a number of houses across England, almost in a form a house arrest.

She died in Kimbolten Manor (to the south of Peterborough) in 1536, and following her death Henry refused a state funeral in London, so Katherine was buried in Peterborough Cathedral in a ceremony that included four bishops and six abbots, a large number of mourners, with the ceremony being lit by 1,000 candles.

Katherine of Aragon is at a point in history where it is interesting to speculate “what if?”. If she had given birth to a son, Henry would probably not have needed to divorce Katherine, and the separation with Rome and the dissolution of all the religious institutions across the country, and the establishment of the Church of England, may not have happened.

Henry did divorce though, and for almost 500 years, Katherine of Aragon’s body has rested in Peterborough Cathedral.

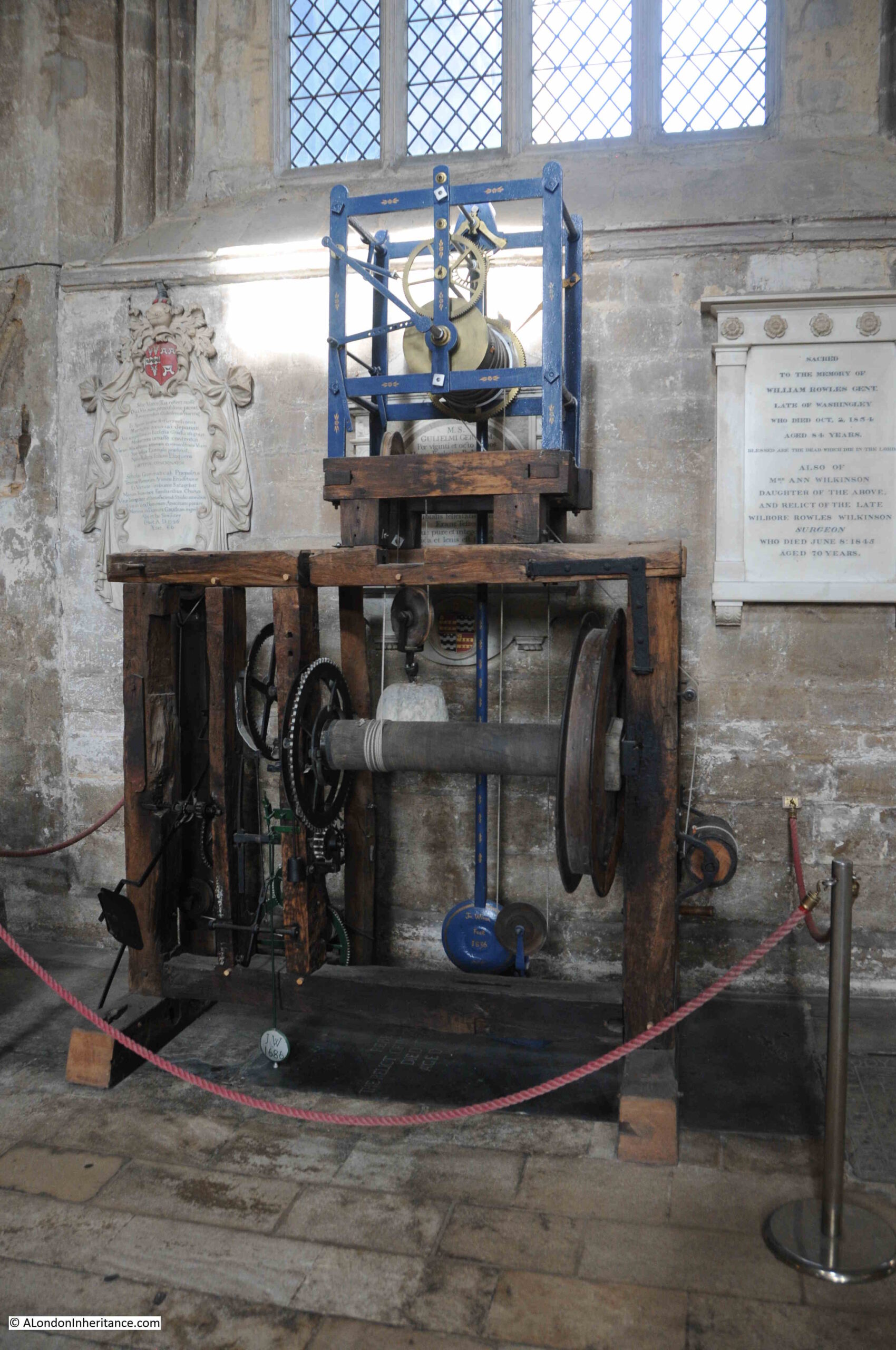

There is a clock mechanism in the cathedral that has the name of “The clock with no face”, as the clock does not have any clock face or hands. The mechanism instead would strike a bell every half hour so the monks would know when to pray, although how they new what the specific time was, I have no idea.

Parts of the mechanism date from about 1450, and it was installed in the bell tower until 1950, when it was replaced with an electronic device. Still able to work, it is now on display in the cathedral:

A magnificent painted ceiling above the altar:

A final look back towards the eastern end of the cathedral. This is the earliest part of the building as construction started in the east and worked towards the west:

Peterborough cathedral is magnificent. The old Guildhall building hints at what the old town of Peterborough may have looked like, before a combination of wartime bombing and post war development changed much of the core of the city.

Very much worth a visit though, and I am pleased to have visited the location of some more of my father’s photos.

I shall be returning to his London photos in next week’s post.

A brilliant article, well done and thank you.

There is a motte and Bailey castle situated to the rear of the cathedral. It is not visable from the cathedral or adjoining streets (as it is now in someone’s garden). It cannot be seen from ariel photographs either because it is covered by trees; but it shows up clearly using LIDAR finder.

I went there in 2019 and found it the whole place fascinating.

My impetuous was to see the massive low relief mural carved by Arthur Ayres in 1955 which of late has been moved to a new location. It’s a truly marvellous piece of work. There’s lots more sculpture by Ayres in London such as on The Adelphi building, overlooking Embankment Gardens, in Queen Square, Bloomsbury, and on the old gas showroom, Crouch End Broadway.

Very enlightening!

Thanks. A thorough description as always. I aim to visit next time I’m in the area.

Thank you for this post loved it

My late wife and i visited many cathedrals over the years and have always been impressed by the high quality of the work both on display as artwork and of course the architecture which in all cases is spectacular. Sadly I don’t ever remember going to Peterborough cathedral but I agree with you the place is a monument to the artistry and dedication of the many people involved in works of this nature. In particular the so called new building . Although it is rather ironic how a structure of the 15th century can be so called. But the British history is full of such quirks.

Sadly they are also testament to the cruelty loosed on the local people by the zealots and hypocrites who are either extremists in favour of these institutions or bigots who are violently opposed to the very existence of such buildings, monuments and institutions.

I love your posts, so interesting. Thanks for putting such much work into them.

Will hopefully visit soon