In August of last year, I was standing on the Stone Gallery of St. Paul’s Cathedral on a beautiful sunny day with London looking fantastic in all directions. I had my iPad with me which contained photos my father had taken from the same place just after the war, showing a very different London. I covered these photos in two posts which can be found here and here.

Looking at the devastation caused by wartime bombing, it was remarkable that St. Paul’s survived relatively unscathed. How had this happened, and what would it have been like to have experienced such a dramatic event in London’s history?

I wanted to find out more, and I have written two posts consolidating the results of some research carried out since that August day. I decided to pick one day’s events to provide some focus. The bombing on the 29th December 1940 caused fires of such intensity and scale that it became known as the 2nd Great Fire of London and from a distance it appeared that St. Paul’s would be lost.

I have split this across two posts which I will publish over two days on the 3rd and 4th of January 2015. This post covers the St. Paul’s Watch, the volunteers who protected the Cathedral during the war. The second will cover the night of the 29th December 1940, the 2nd Great Fire of London.

My apologies for the length, however I hope you will find these two posts as interesting to read as I did to research. (Unless otherwise stated, in this post, all photos and documents are from the St. Paul’s Cathedral Architectural Archive).

So let’s start with:

The St. Paul’s Watch

In the months leading up to the start of the 2nd World War, there was much preparation in London for what was expected to be a devastating war from the air. Limited bombing during the 1st World War had shown the possibilities, further developed in the Spanish Civil War and then by the Blitzkrieg or lightning form of mechanised warfare used by Germany in the attack on Poland which was the catalyst for bringing the UK into formal war with Germany.

St. Paul’s Cathedral was considered at high risk from aerial bombing. Unlike today, the Cathedral was by far the tallest building in London, standing clear on one of the two hills that formed the original City. Not only was the Cathedral an architectural masterpiece created by Wren, one of London’s main architects after the Great Fire, it was a central landmark in the life of Londoners and to the nation.

In the month’s leading up to the start of the war, the Cathedral started to prepare. On Saturday, 29th April 1939 one of the regular meetings of the Chapter of St. Paul’s was held, and although a regular meeting, this day’s session was different, it was to start planning for how the Cathedral could be protected.

During the 1st World War, a volunteer watch had been kept at the Cathedral and it was along these lines that planning for the new threat was made, with the creation of a volunteer Watch who would have responsibility for defending the Cathedral against any form of aerial attack.

Mr Godfrey Allen, the Cathedral Surveyor was appointed to command the Watch and preparations were made to put the Cathedral onto a war footing.

One of the first challenges was to find sufficient manpower to mount a fulltime, day and night watch over the Cathedral. This was at a time when the majority of the able-bodied, younger male population was expected to be involved within the armed forces. The Cathedral Watch initially started with 62 volunteers from the Cathedral staff, however this number was not sufficient to maintain a full 24 hour Watch over the Cathedral and many of these volunteers were also approaching retirement and when action was needed across the heights of the Cathedral, in the roof spaces, under the Dome etc. additional support was needed.

At the suggestion of Mr Godfrey Allen, a request by the Dean was made to the Royal institute of British Architects (RIBA) for volunteers to join the Watch. RIBA was a perfect match with members having knowledge of architecturally complex buildings and therefore perfectly suited to working in a building such as St. Paul’s and the age profile of experienced architects probably made a larger pool of people available.

The Dean of St. Paul’s made the following appeal:

“St. Paul’s Cathedral is in urgent need of double the present number of Firewatchers. The average strength at the moment is about 20 men a night. Dr. W.R. Mathews, the Dean, is sending out an appeal for volunteers and his first letters have gone to the Royal Institute of British Architects and to the High Commissioners for each of the dominions. He stated yesterday that the work is interesting and volunteers have the unique privilege of being given the freedom of the Cathedral. They are expected to watch one night a week; but the hours of duty can be adjusted to suit individual requirements. The watchers are required to be at the Cathedral not later than 9.30 PM. Subsistence allowance is paid and bunks, blankets and mess room accommodation are provided.”

I would have thought that being given the freedom of the Cathedral would have been a considerable incentive for anyone interested in the architecture and history of the building.

The appeal was successful as another 40 volunteers came forward, with the first full meeting held on the 15th September 1939 and from the 25th September a regular “night shift” from 9.30pm to 6.30am was maintained.

Whilst the Watch was made up of volunteers, it was far from an amateur operation. Under the guidance of Godfrey Allen the Cathedral was prepared and the members of the Watch participated in an extensive series of lectures, training and exercises to prepare them to work in the expected intense bombing to come.

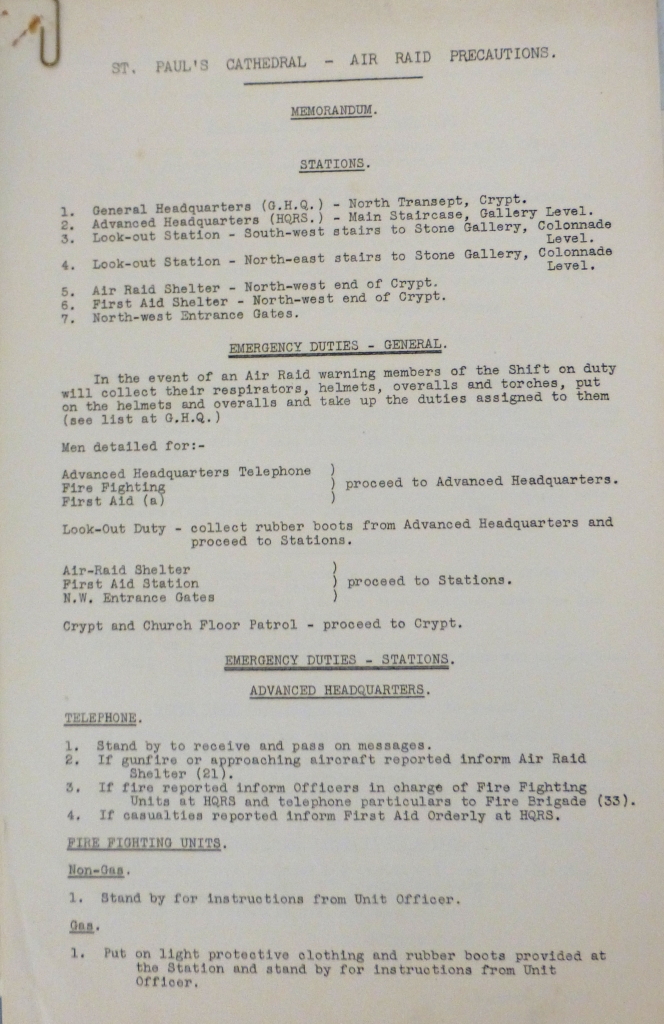

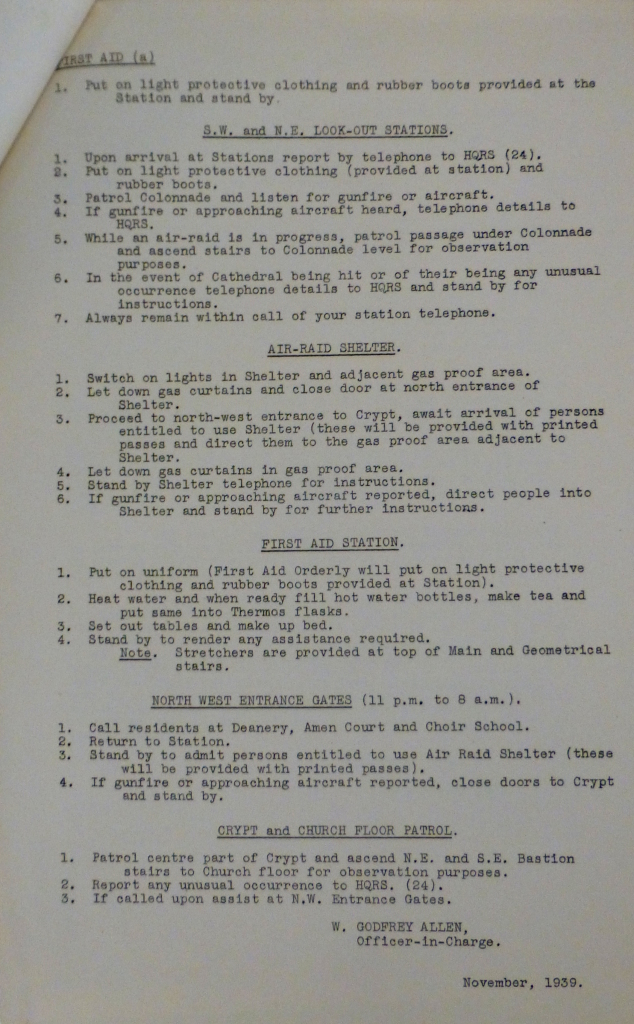

Many of the original lecture notes and training material remains in the archives at St. Paul’s. The following two pages are the initial Air Raid Precautions documented in November 1939. The level of planning and preparation is very clear and highlights what is needed to protect such a complex building as St. Paul’s.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

Note the reference to “gas proof area” and “gas curtains” in the following page. This was before any serious bombing had commenced and there was still an expectation that as well as explosive bombing, London would also be attacked with poisonous gas. Exercises included first hand experience of gas. A hut in Cripplegate was used to provide the experience of passing through a chamber filled with tear gas. Fortunately this was to be the only contact that London and the members of the Watch had with the much dreaded gas.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

The complexity of St. Paul’s, the numerous stairs, small corridors, access to roof spaces, access to the external roofs, access to the interior of the Dome etc. were a considerable challenge for those volunteering and without an in-depth knowledge of the building. Many sessions were held, training the members of the Watch to find their way around the Cathedral. Where to find equipment, water supplies, telephones etc. and to be prepared to do this whilst the Cathedral was in the dark, being bombed, on fire and with the constant threat of high explosive bombs.

To give some idea of the types of small corridors that connect different parts of the upper building, the following are two photos that I took on the way to the Archive.

Adding to the challenge of trying to get to the site of a fire, the Watch would probably have to work through these corridors by torch-light whilst carrying tools and buckets of water. Remove the electric lighting, cabling and pipes and these corridors are probably unchanged since the time the Cathedral was originally built.

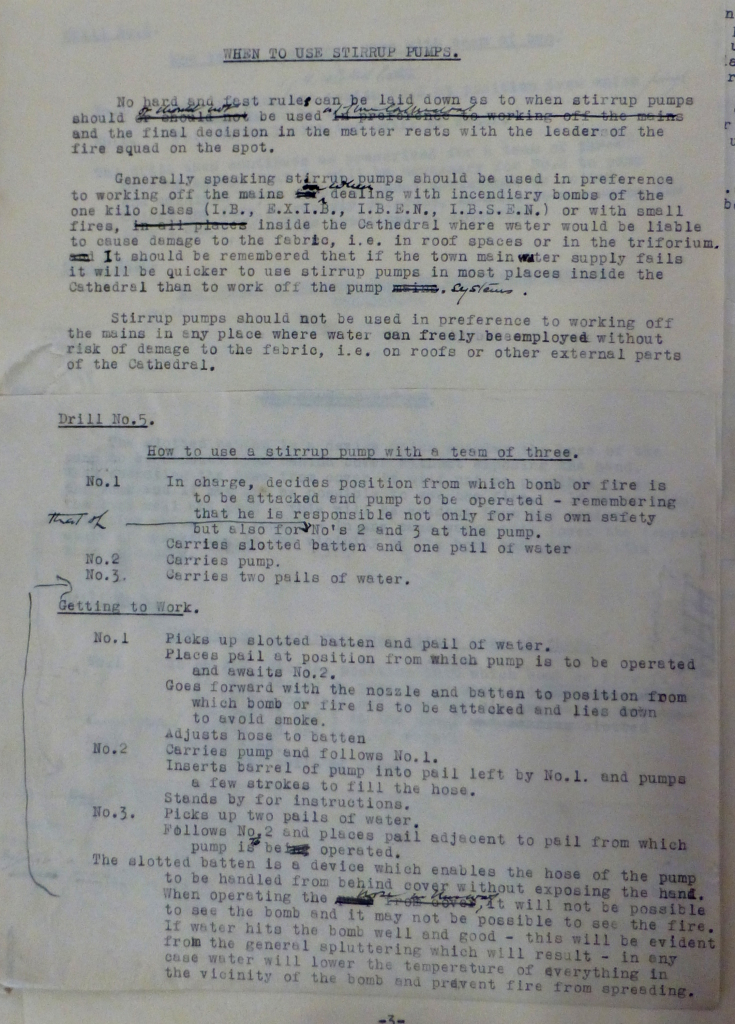

There were a number of key factors to be considered when fighting a fire.

Large quantities of water could do damage to the fabric of the building. There was a balance to be achieved with using the right approach to extinguish a fire without causing undue damage to what is an architecturally complex and delicate building.

There was the issue of access to difficult locations. In a building as complex as St. Paul’s with many small, hidden locations, access to a large quantity of water was just not possible.

And availability of large quantities of water was always a concern as would be demonstrated on the night of the 29th December 1940. Water would be required not just for St. Paul’s, but also to protect all the buildings in the City. Storage was a problem, the River Thames was tidal and bombing could also damage the pumps extracting water from the river and the complex pipes and hoses bringing water up from the river along the City streets.

One of the key tools in use by the St. Paul’s Watch was the Stirrup Pump. The following photo from the Imperial War Museum collection © IWM (FEQ 864) shows a typical Stirrup Pump in use by the St. Paul’s Watch:

The Stirrup Pump was in such great demand as a fire fighting tool that at one stage, just a single factory in 1941 was producing 10,000 a week. As with all other areas of the Watch, there were detailed instruction and training in the use of the Stirrup Pump.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

It is interesting to read in one of the introductory lectures that the Cathedral was classified as a “business premises” with the Dean and Chapter being the occupier. As the occupier, their responsibilities were clearly defined as:

- for organising the fire watch;

- for supplying equipment, appliances and water;

- for the instruction and training of fireguards;

- for keeping a register of all attendances and defaults;

- for giving directions as to the place and time the fireguards are to perform their duties;

- for providing sleeping accommodation, bedding, adequate sanitary arrangements and lighting;

- for providing facilities of access to all parts of the building, except such parts as may reasonably be excluded

As well as the Watch, St. Paul’s was also prepared for the possibility of direct bombing by the removal of all that was possible to remove and the protection of anything that could not be removed.

The Grinling Gibbons Choir Stalls were dismantled with the more valuable pieces being sent out of London, the rest being stored in the crypt. The ironwork gates by Tijou along with Wren’s model of the Cathedral were also sent out of London. The rarer books were sent from the Library to the National Library of Wales.

Statues and busts which could be moved were relocated to the crypt. For anything that could not be moved, for example the memorial tablets to the Wren family, they were bricked in to provide some degree of protection.

There are a number of photos in the Cathedral Archives that show the Watch. These appear mainly to be posed photos, possibly for newspapers and magazines, however they provide a very good record of the Watch and their working conditions.

A lecture class given in the Stewards Office:

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

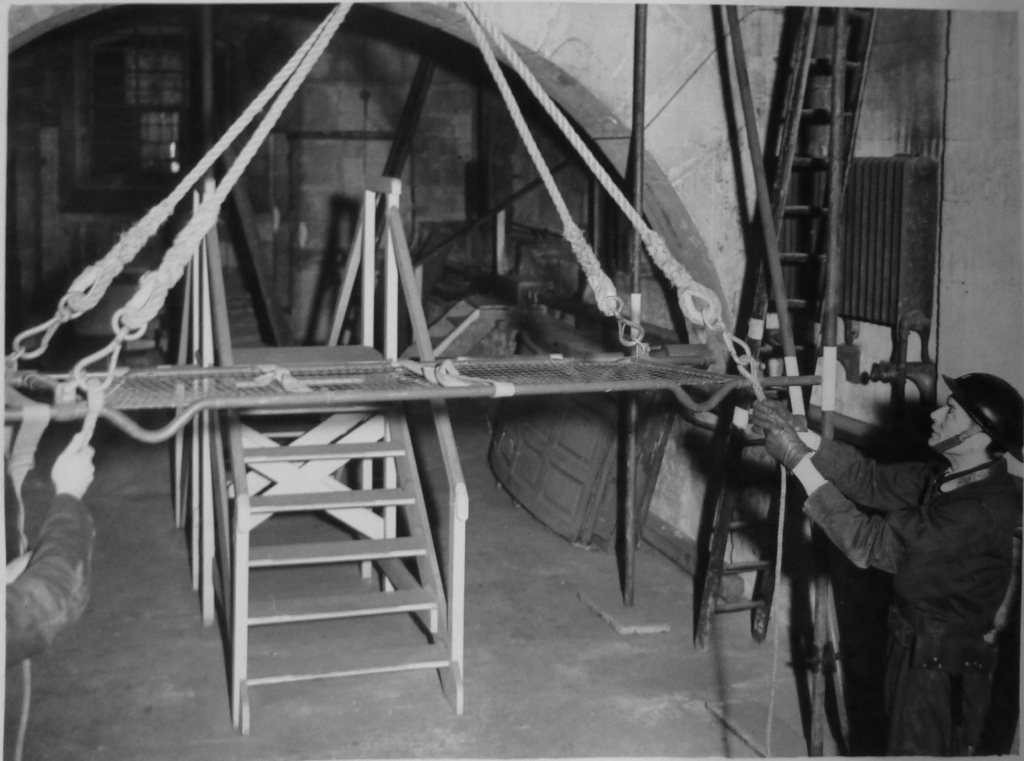

The following photo shows Stretcher Practice in the Dome galleries. In preparing for any bombing, there was a very real concern that the Watch could suffer injury. The Watch would not have waited until bombing has ceased to go out and fight fires, the Watch would have been across the roofs, in the Dome etc. looking out for damage, fighting fires and checking for incendiary bombs that had lodged in hidden parts of the Cathedral in the middle of raids.

Bringing those injured down the long stairs from the upper reaches of the Cathedral was not considered practical, therefore arrangements were in place and tested to lower casualties on stretchers over the edge of the upper areas (for example the Whispering gallery) and lower them down to the ground floor of the Cathedral. I am not sure what would have been more frightening, the external threat from bombing, or being lowered in one of these from the great heights of the Cathedral.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

Another photo showing stretcher lowering being tested:

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

The risk of injury or death was not just when on Watch in the Cathedral. The journey into the Cathedral was just as intense. From St. Paul’s Cathedral in Wartime by the Dean of St. Paul’s:

“Many of our members came from distant parts of London and the task of getting to St. Paul’s on many a noisy night might have daunted the stoutest heart, but it did not daunt the Watch. They came through darkness, falling shrapnel from our guns, and the debris of wrecked buildings, sometimes having to throw themselves on the ground when a bomb fell near, on foot or on bicycle when other transport failed, they came to keep their Watch, whilst those they relieved made similar nightmare journeys home. Men at the look-out posts on the roof glanced occasionally towards their homes and offices wondering what they would find there on the morrow. Some saw their homes go up in flames, but they did not flinch”

This rather puts the modern-day irritation of a delayed train on the way home in context.

The following photo shows members of the Watch at one of the advance locations around the Cathedral:

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

And another similar photo:

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

Locations were set-up around the Cathedral that could be used as waiting and reporting points and to control specific areas of the Cathedral. Each was equipped with a telephone to enable reporting back to the Control Station in the Crypt of the Cathedral.

These photos also show the ages of the Watch. In 1939 conscription covered males of between 18 and 41 and by 1942 this has been extended to the age of 51. This would have limited the pool of men available to the Watch only to those over the age of conscription.

The remainder of 1939 and the first half of 1940 was relatively quiet for the Watch. Training progressed, exercises were performed and the Cathedral was prepared as best as possible for what was still a threat that whilst imagined had not yet been experienced.

Bombing of central London of any intensity started in August 1940 when on the 24th there was some limited bombing of the City with two bombs near the Cathedral. The first air attack took place on the 7th September when an attack was concentrated on the London Docks. Members of the Watch experienced this first major raid from the high points of the Cathedral. From the Dean’s book:

“It was a golden, peaceful evening and, as the light faded from the sky, the angry red glow in the east, diversified by leaping flames, dominated the prospect, while from time to time the peculiar thud of bursting bombs punctured the silence. We were a silent company as we gazed upon the apocalyptic scene, each no doubt pondering many things. We noted, without remark the apparent absence of defence – an observation which we were to make often in the next few weeks. We wondered how long it would last before the attack moved westwards to the heart of London. We feared that the whole port of London was being annihilated. At last someone spoke, “It is like the end of the world,” and someone else replied, “It is the end of a world””.

For the Watch training and preparation continued. Note the Watch members assigned medical tasks in the following photo with the cross on the white helmet.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

Axes and hoses were key components of equipment, however hoses were very dependent on having a readily available source of water under pressure.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

The availability of water was a constant issue for the Watch team. As would be found on the 29th December 1940, when water from the River Thames could not be relied on. Damage to pumps and pipes was always a risk, but also low tides in the river which took the main body of water below the level of the intake pipes.

The Cathedral had then as well as now a riser system providing distribution around the Cathedral:

However in the event of mains supplies of water failing, these would be of little use. The Watch team prepared the Cathedral by storing supplies of water in all areas of the Cathedral using any form of container that could hold water. This would be invaluable in fighting the fires on the 29th December.

The area to the immediate north of the Cathedral was destroyed in the raid of the 29th December. In the following months the buildings were cleared and water storage tanks installed. The outlines of these were still visible in the photos my father took from the Stone Gallery after the war. The following photo taken from the Cathedral shows the tanks in place, a couple of which can be seen in the lower right of the photo.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

Following the initial raids, the St. Paul’s Watch settled into a routine of periods when there would be intense activities, raids almost daily for a number of months, followed by periods of quiet, a time to regroup and repair damage.

The Watch were critical in protecting the Cathedral from fire and the huge amount of incendiary bombs that fell on the City. The Cathedral suffered a few direct hits from high explosive bombs during the war. The following photo shows bomb damage in the North Transept caused by falling debris.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

The Cathedral had a very narrow escape on the 12th September 1940. The night had been one of intermittent attacks and in the early morning a high explosive bomb fell very close to the South West Tower. It narrowly missed the tower by a few feet and penetrated deeply below the road surface. The bomb did not explode, but due to the soft clay beneath the surface, the bomb gradually sunk deeper, eventually to reach a depth of 27 feet 6 inches below the surface.

The bomb was removed on the 15th September and taken to Hackney Marshes where the bomb was blown up, it left a crater 100 feet in diameter. Had the bomb exploded on impact it would almost certainly have taken out the whole of the South West Tower and much of the West front of the Cathedral.

There was very little that the Watch could do with an explosive bomb. If one hit the Cathedral it would explode on contact, any bomb that did not explode, either due to a fault or a delayed action fuse, was left to the professional bomb disposal teams.

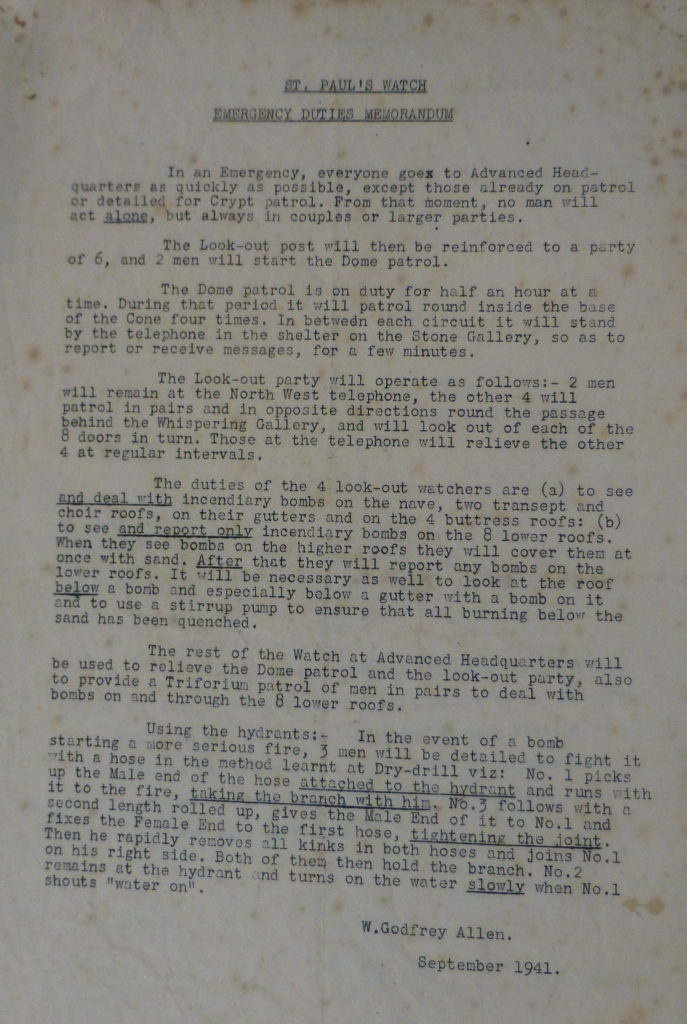

Emphasis for the Watch was always on the roofs of the Cathedral, the Dome and the risk of fire. The following memorandum from Godfrey Allen in September 1941 details the duties and procedures to be used in an emergency.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

The Dome patrol was critical to ensure that a fire could not get hold in the timbers supporting the Dome. The Dome must have been a strange place to be during the height of a raid. In his book, W.R. Matthews recorded that:

“The Dome was not a healthy place in the height of a blitz and the patrol was changed at half-hourly intervals. Men have told me of the awesome feeling they experienced when carrying out their patrols in the darkness of the Dome while the battle ranged around them and of how the din seemed to be magnified by the Dome, like the beating of a drum. If they had any compensation it was perhaps that of witnessing from their lofty perch of the Stone Gallery the spectacle of the Battle of London as few others can have seen it.”

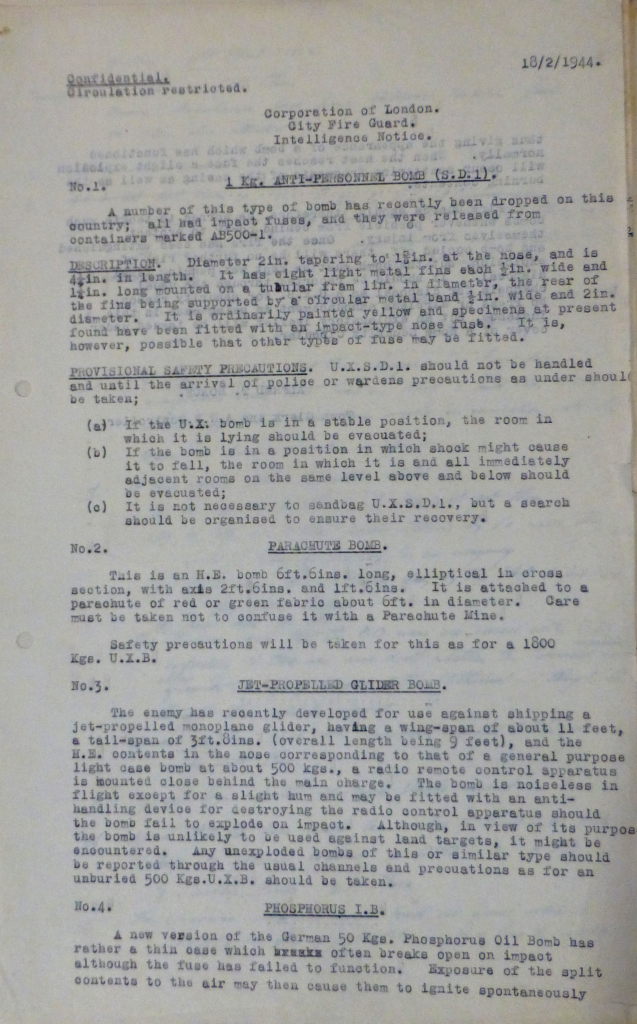

Training continued throughout the war, the types of threats continued to evolve and updates from the appropriate authorities provided the Watch with information on the threats they may have to face.

The following two pages are an Intelligence Notice from the Corporation of London detailing new models and versions of bombs.

- A 1Kg Anti-Personnel Bomb

- Parachute Bomb

- Jet-Propelled Glider Bomb

- A new version of the Phosphorus Incendiary Bomb

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

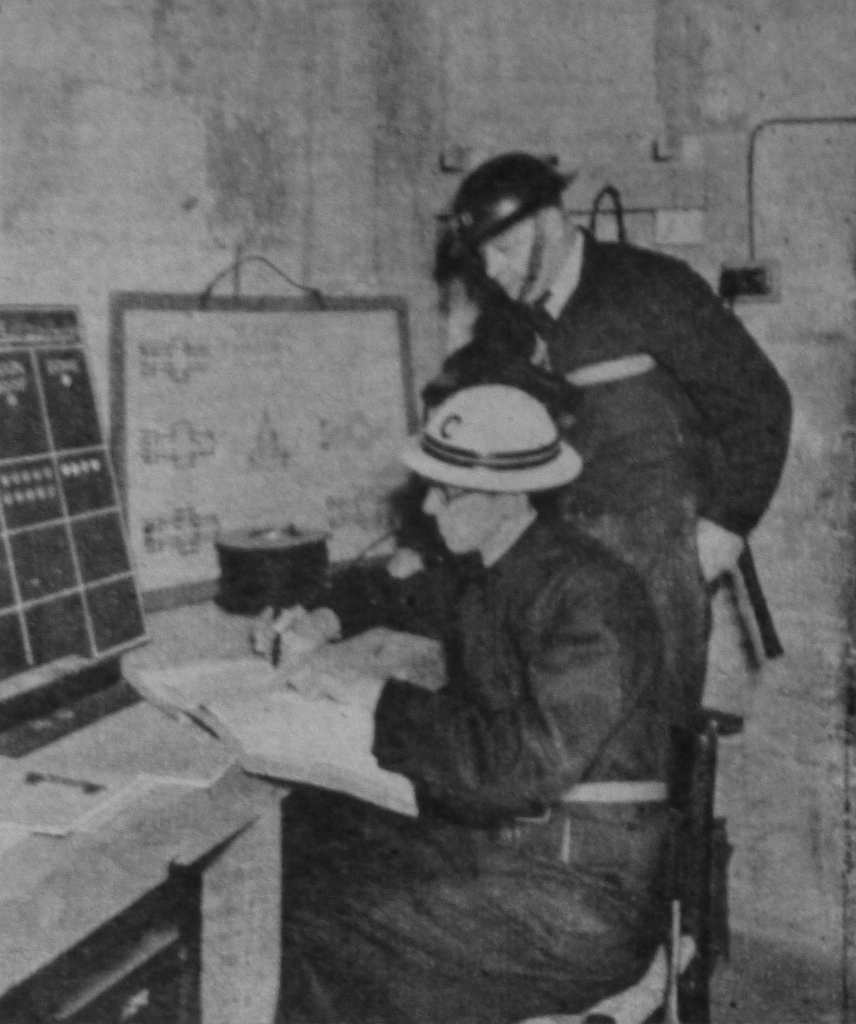

In researching the work of the Watch, one name keeps recurring, whether as the author of much of the training materials and instructions for how the Watch should operate, to the very limited number of books that have been written about the Watch. Godfrey Allen was the Surveyor of the Fabric before the War (he held the post from 1931 to 1956) and took on the command of the Watch for the duration. It was not only his intimate knowledge of the construction and layout of the Cathedral, but also his organisational abilities in moulding the Watch into the team that protected the Cathedral during the height of the blitz. He was also responsible for the immediate repairs needed to those parts where bomb damage had been suffered, both the immediate repairs to protect the building from the elements, but also the long-term repairs.

Before the war, Godfrey Allen was also responsible for the St. Paul’s Heights policy. These were put together in the 1930s following the construction of The Faraday Building and Unilever House, which started to obstruct the views of St. Paul’s. The Heights Policy has remained in force ever since and is now part of the Local Development Framework of the City of London.

Mr Godfrey Allen (in the white hat) in the crypt control room.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

The Dean of St. Paul’s wrote at the end of the war “If any one man could claim to have saved St. Paul’s, that man is Mr Allen”.

The Christmas and New Year card sent by Godfrey Allen to members of the Watch for Christmas 1940, during and continuing into the peak period of the London Blitz.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

During the latter stages of the war, there were no threats to the Cathedral (apart from the period of V1 and V2 rocket attack), however the Watch still maintained a nightly vigil. To help with the monotony of nightly exercises the Watch organised a series of lectures and the following provides an example of the lectures from one week in January 1945:

| C.A. Linge | The Preservation of Durham Cathedral |

| J.D.M. Harvey | Time |

| J. Steegman | Iceland to Istanbul n Wartime |

| R.M. Rowett | Women in Poetry |

| P.B. Dannett | Some Lantern Slides, Record and Pictorial |

| Basil M. Sullivan | The People of India |

The Watch continued until the very end of the war in Europe. The “stand down” of the Watch was arranged and an act of worship planned for the final meeting of the Watch on the 8th May 1945. By coincidence, this was also the day that the German forces surrendered, VE day and the Cathedral was crowded all day long with frequent services held from early morning to dusk (an estimated minimum of 35,000 people attended the services during the day along with countless others who called into the Cathedral to mark the day’s events). The final meeting of the Watch took place at the end of the day’s public events.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

One of the closing paragraphs from Godfrey Allen’s reply to the Dean during the Service of Thanksgiving sums up what the members of the Watch must have felt at the end of such an intense period in their lives as well as in the history of St. Paul’s and London.

“To many of us, I am sure, these years will prove to be the most memorable of our lives and when we recall them in the quiet of our homes we shall think, not only of the horror and waste of those dreadful days and nights, but also of the great building which bound us all together and for which we fought with all our might.”

To provide a lasting reminder of the work of the St. Paul’s Watch, the following tablet was set in the floor by the western end of the Cathedral:

In tomorrow’s post I will cover the night of the 29th December 1940, the impact to the area around St. Paul’s Cathedral, and how the Watch protected the Cathedral from the surrounding devastation.

The sources I used to research this post are:

- I am very grateful to Sarah Radford, Archivist at St.Paul’s Cathedral for providing access to the documents covering the St. Paul’s Watch

- The Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral during the war, the Very Reverend W.R. Matthews published a comprehensive account titled St. Paul’s in Wartime published in 1946 (this article only scratched the surface of the work of the Watch. I recommend this book for a detailed and very readable account)

- St. Paul’s In War and Peace published by the Times Publishing Company in 1960

What a fascinating, moving and intriguing post. I knew a little bit about the effect of bombs and incendiaries on St Pauls during WW2, but nothing about the Watch. You have brought this story to life, David. Wonderful stuff, and I can’t wait for tomorrow’s post….

Thanks Vivienne. It was fascinating to research and to read the original documents in the St. Paul’s Archive was such a real link back to these people and events.

Do you know whether any of the Fire Watch are still alive and in contact with one another? My father John Middleton was a member and is still living independently in Oxfordshire.

Hi Joanna, wonderful that your father was in the St Paul’s Fire Watch. I do not know if there are any other members still alive. A place to start could be the Friends of St Paul’s Cathedral. There is a contact e-mail address at the bottom this page. https://www.stpauls.co.uk/support/st-pauls

If there is anyone who could help, I suspect they would know.

Thank you – I will contact the Friends!

This was fascinating, thanks. I hope Mr Allen was properly regarded and rewarded after the war.

He was certainly well regarded by the Dean of the Cathedral. I did not find any record of any other reward after the war. He lived in Faversham and his former home is commemorated with a plaque http://www.faversham.org/history/wall_plaques_-_people/walter_godfrey_allen.aspx

Fascinating – thank you !

Really excellent to read – My father was on the St Paul’s Watch at the beginning of the war – arriving from the Architectural course at the Regent St Poly. I will contact Sarah Radford and try to learn more !

Thank you again, Jolyon

My late father in law, Philip Bell, was also a member of the St Paul’s watch as a result of being a student of architecture at the Regent Street Polytechnic. We had no idea that the watch was this well organised, so this has been a fascinating insight. We also will try to learn more!

Rev Matthews wrote a book detailing this period and the St Paul’s Watch – it may be of interest. Dennis Flanders and Gerald Cobb were contemporaries – they would have known Philip. Peter was a lifelong friend of Philip and Chris.

In this photograph, Peter is in the middle – no doubt you will find Philip and his contemporaries from the Regent St Poly there too.

https://www.stpauls.co.uk/SM4/Mutable/Uploads/imported_media/From_the_image_archive,_members_of_St_Paul's_Watch_during_WW2.jpg

Wonderful! Thank you so much for including this picture. My father in law, Philip, is seated second from the left in the group of 4 seated men on the left of the picture. He would have been about 20 or 21 years old at this time. We will certainly try to get hold of the book by Rev Matthews. I knew that your father, Peter, was best man at Philip’s wedding and remained a lifelong friend.

Do you know the name of this book, I would be interested in finding it as My Grandfather was in the Watch I believe and I am hoping to learn more about this.

David I have a spare copy of the book No. 614 out of the 2000 printed and it is signed by Rev W.R. Mathews. It does not have a dust jacket but it is in very good condition. I can sell it for what I paid which was £25 + p+p if you are interested. I can provide photos if you wish. dgpmorse@btinternet.com

My father Thomas Alpha Newby was in the St. Paul’s watch before he was called up in 1940. He was a professional singer – a Lay Vicar Choral in the St. Paul’s Cathedral Choir before and after the war.

Disappointingly, this link does not work for me – it goes to Page 404 Not Found.

I have a scanned copy of this picture which I can send to you if you wish. I’ll either need your email address, or I can try to send it via WhatsApp or Messenger if you are on these. If you don’t want to make your email address public by replying here, I’ll go through WhatsApp to see if I can find you. Let me know if any of these suggestions meet with your approval.

Thank you for this fascinating piece of research. What a huge debt of gratitude we owe to the Members of the St Paul’s Watch! When I look at the floor plaque of remembrance to them, I feel so proud.

My father loved the City of London and St Paul’s Cathedral. He worked in an office in St Paul’s Churchyard shortly before the war, and often visited the Cathedral during his lunchtimes. He used to tell us that people were not allowed to take a newspaper into the Cathedral, because this was political.

He described the old, narrow, winding streets near St Paul’s, which he explored, before the War and the Blitz, and the wonderful perfume which wafted from Grossmiths Perfumiers. His office building must, tragically, have been destroyed during the Blitz. I have often wandered past to see whether I could distinguish any trace of it. I don’t think it is there now.

Thank you so much for compiling all this information and telling the story so well. I found your blog on what could be described as a goat’s trail. I bought a book called “london in Pictures”, which was published in the 1950s and there was a typed 3 page letter inside: “My Trip To London”. It provides a walking tour of London and I’ve gone onto Google maps trying to put it together. This has been an “interesting” experience as my poor sense of direction is just as much a problem there as real life.

I have only spent a week in London back in 1992 as a 21 year old.

My grandmother, Eunice Gardiner, lived in London from 1936-1940. She received a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music and returned to Australia in February 1940. She had a monthly TV show with the BBC and was due to appear the day after war was declared but the TV was shut down.

I have been following Geoff Le Pard’s blog for a few years now and he has done some wonderful tours around London and also posted some love letters his father wrote to his mother just after the war, which I think you’d like: https://geofflepard.com/dads-letters-the-story-of-a-1940s-love-affair/

xx Rowena

Thank you for the very interesting post.

I looked up the St Paul’s Watch after reading the short story “Fire Watch” by Connie Willis, which might be interesting for you.

Can anyone tell me if St. Paul’s was open to the public and/or worshipers during the later years of WWII?

I’m not speaking of the time of the actual Blitz, but of 1943, 1944 or early 1945. Also, I’m not asking so much if regular services were performed, but rathercouldf someone could walk in off the street and stop and say a brief prayer and then turn and exit the cathedral? Thanks for input from any or all.

Ed, I’ve just picked up your questions. Better late than never! At the start of the war the Dean and Chapter forbade anyone from sheltering in the Cathedral during the earliest raids. This was before the deep air raid shelters were dug and before people were officially allowed to sleep in the underground stations. After a short while, however, the authorities relented and on the first evening that they allowed people to stay in the Cathedral overnight, I believe, some 10,000+ collected inside. You must remember that surrounding the North and East of the Cathedral was a great deal of densely populated civilian housing of one sort and another which effectively got wiped out during the 29th December raid. I hope this helps.

hello

that was very informative

i am from canada with broken wrist (hence poor typing) but cannot seem to locate a video documentary of the actual footage of the fire watch saving st pauls

would you know where i might locate it?

My father, Alfred Henry Sharr was on the staff at St. Paul’s starting in the late 1920’s and was a member of the St.Paul’s Watch. He is in the first picture of the Watch members – helmet # 168. He stayed on at the Cathedral until his death in 1962, and pictures of him include him climbing the dome, and standing on the cross. He seldom spoke of the war years, but knew the Cathedral from top to crypt, and often took me to see hidden corners.

My father Francis George Elliott (Frank) Jones often talked about being on Fire Watch at St Paul’s. He was in the Auxiliary Fire Service, I think with a furniture store possibly called Edmunds, or Edwards in Tottenham where he lived after he came out of the RAF.

My father Frederick William Eyre tanner joined the fire watch after being blown up & told to take life easy. I wish I had remembered more. He had a head for heights so carried buckets of sand & water for the stirrup pump up to the walkway around the Dome. it was all they had, so he adapted a tree lopper into a “grab” for incendiary fire bombs to flick them down into the churchyard below to burn out in safety. One stuck in the roof just out of reach & lead started to melt so in desperation he thumped the long pole By a miracle it was dislodged. He was proud to be a member of the Fire Watch to be a small part of the Team that saved St. Paul’s the cathedral he loved. He ended up Treasurer of Holdenhurst, mother church of Bournemouth.

My father John Middleton was a member of the Fire Watch and joined as an ‘apprentice’ architect as a very young man – he was only 20 when he was posted to Japan in 1945 for the surrender, which may explain why he is not in any of the photographs (at least as far as I can see). I don’t think he received a Fire Watch badge either, but he is listed in the book about the Fire Watch. He is still very much alive and living in Oxfordshire. I wondered if there would be any commemorations this year (despite everything)?

My father-in-law, Philip Bell, was in the St Paul’s fire watch as a young student of architecture at The London Polytechnic. Sadly he is no longer alive (he would have been 100 at the end of this month). I have a wonderful picture of the entire watch sitting on top of a building adjacent to St Paul’s. We can identify my father in law, as well as his best friend, Peter Yates, who was also a member. I am happy to share this with you in the hope that you may be able to identify your father…or, indeed, he may be able to identify others who are there! I’m not sure how to achieve this sharing without making email addresses public which is clearly not appropriate…….

There is an interesting book by the Rev Matthews about The Watch. If you can source a copy, I am sure your father would find it fascinating.

Thank you so much for your response. I did see the wonderful photograph of the entire watch on this website but was disappointed to see that my father was not in the picture – do you know the date of the photograph? His name is listed in Rev Matthews’ book and he does have a copy which we managed to obtain a few years ago.

I don’t know the exact date, but it would have been early on in the war. My guess is that it would be 1940, or possibly 1941. Late on in the war my father-in-law transferred to firewatch duties on Hampstead Heath.

Mike Macey,

I have looked at the list of NIGHT Volunteers for the St Pauls Watch which appear in the book written by the Dean, St Paul’s Cathedral in Wartime and your fathers name does not appear. That’s not to say that he did not just attend during the daytime shifts. You could do what I did and send an email to Sarah Radford the Cathedral Archivist and ask if you could visit when able to, to look at the roster books. I have photo copy of the roster for the 28th December and Macey does not appear. I also have a photo of the main group of the watch. I could not find my Grandfather on the photo. He is mentioned by my Aunt Olive Rosson in one of the above comments. I have a spare copy of the Deans book available for sale. I am happy for the ADMIN to email my email address to you so that I can send you further info if so desired.

He would have perhaps also been seconded from the Regent St Polytechnic, where Philip Bell and Peter Yates were studying architecture under Sir Hubert Bennett and Peter Moro. If so, I wonder if a student list of the from that time would help him to find any surviving friends? (Peter Yates bio at http://www.peteryates.co.uk)

I have never tried to find out about my father’s service on fire watch duties in London. He never mentioned much about it. He did tel me about the unexploded fire bombs on St Paul’s so I do not know if that was first hand knowwledge or not. He was born in 1903 and only had one eye so he could not srve in the forces. He worked in Covent Garden market througout the war. His name was Frank William James Macey

My mother never talked about the war eeither but slipped up one day and mentoned that she had been a sectretary at the Bank of England in underground offices.

Thank you so much for your reply.

My father worked inCovent Garden throughout the war and would, I suspect, have ben available during the afternoons and early evening at most, as he needed to be a sleep early for a 3.30 am rise. He hitched lifts all his life as buses were too unreliable.

My mother apparently worked underground as a secretary for the Bank of England but by mistake let that slip one day and clammed up immediately and never referred to it again.

My father was apparently the only German national on the watch, unusual, and often frustrating for him as he had a strong accent and had to be introduced as a friendly face to new members each time someone new joined his group. He lived on the grounds of Kensington Palace and his stories of his treks to the cathedral were something else again.

Interesting view of the V-1 as an anti shipping weapon and unlikely to be used on land as early as February 1944.

My grandfather Charles LARDNER always said that he was a fire watcher at St.Paul’s. He worked close by I believe and told us of being in the crypt of a night. Is there anyway of checking to see if if this was correct? We have no family records. There is a man in one of the pictures that looks the spitting image of him and the helmet no. seems to say 146? Any help gratefully received.

Paul,

Beware. One of the photos shows one of the Watch on the right and he has definitely 156 on his helmet. I know because he is my Grandfather.

Paul,

Beware. One of the photos shows one of the Watch on the right and he has definitely 156 on his helmet. I know because he is my Grandfather. The archives have the logs where the men and women would have to tick to show that they are on duty. You may find a record there.

Thanks David, I am most grateful for the information. That sounds like a good place to start. The resemblance to my grandfather in the picture is to the man at the top of the photo, the number is hard to decipher, would each member have their own numbered helmet?

Like you, my father in law said that he was in the St Paul’s Watch. We contacted the archivist at St Paul’s. She arranged for us to visit and access the relevant archives. We found pictures of him and reference to his fellow student of architecture (who was subsequently his best man) but we didn’t find any written reference. You may be luckier. It is certainly worth doing this!

Thank you Judith, I will contact the Archivist and hope for the best. Do you happen to know whether Fire Watchers were awarded any recognition for their service as Civil Defence?

Hi Paul, Generally speaking Fire Watchers, ARP and the multitude of volunteers who helped protect this nation did not receive any formal recognition other than the uniform or badge that indicated, firstly, that they were doing their bit and secondly in which service they were helping with. There were so many heroes, both male and female, young and old who carried heroic deeds without receiving or wanting any form of recognition. The Watch did have their own gold coloured “Watch” badge. My Grandfather was working for the Cathedral between 1927 and 1962 when he died suddenly at the age of 62 and appears in a lot of the wartime pictures. He was instrumental in setting up the Friends of St Pauls. I gave a talk regarding the Watch to the Friends in the Crypt last September. It’s the talk that I give regularly in and around my home town.

I think your query about recognition has been answered elsewhere. I seem to remember that not too long ago there was a service at St Paul’s at which the contribution by the fire watchers was specifically remembered and commemorated. Sorry that I don’t have any more details.

On the advice of others, I have bought a book called ‘St Paul’s Cathedral in Wartime’ by W R Matthews (Dean of St Pauls) published by Hutchinson in 1946. Obviously it is no longer in print, but I purchased my copy second-hand. It’s a fascinating book, has lots of pictures of firewatchers and in an appendix it gives a list of ‘Night Volunteers’. I haven’t looked to see if your grandfather is listed, but will do so.

I have a wonderful photograph of all the firewatchers sitting on the top of a building next to St Paul’s. I can identify my father-in-law on this. You may be able to see your grandfather. I’m happy to send you a digital copy, but can’t see a way of doing this. I gave a copy to the archivist when we visited St paul’s as it wasn’t in their collection. So-if you visit you could ask to see it.

Hi Judith

I would love a digital copy. I saw a documentary of footage of the Firewarxhers throwing incendiaries off St Paul’s and buildings going down. I’ve never been able to find it since. Can I pay you something for the book? I’m in Canada so can’t nip over to the archivist.

Sorry, I didn’t mean to imply that I was selling the book. I just gave the title, author & publisher as I thought the original enquirer might like to try to buy it second-hand from Amazon or one of the on-line second-hand book sellers. I think you should be able to do this from Canada. I’m happy to share the picture, but am not certain how to do this.

Hi Judith

My misunderstanding. I’ll look about for a second hand copy and thank you for the information. The firewatchers were heroes. Ta

Thank you David. Silly question but were the fire watchers distinct from the ARP or under that umbrella? You must be extremely proud of your Grandfather’s service. How wonderful that you have the photographic evidence.

Paul,

They were a separate group from the local ARP or any of the other groups. But, undoubtedly they would have had some form of training from outside as they were not conversant in fire fighting or medical treating. I am very proud of my Grandfathers service both to St Pauls and to his country in WW1.

Thanks David, that is interesting to note.

Thank you Judith, I would be very interested to discover if his name is listed it was Charles Lardner. My understanding is that he was a boot maker by trade and worked very close to St.Paul’s. This may account for his volunteering there, as his abode at the time was Islington! I think communicating with the archivist is the next step in my journey of discovery. Thanks again, I really appreciate your assistance.

Sadly, he’s not listed, but neither is my father-in-law, so the list isn’t exhaustive. Good luck with getting an appointment with the archivist. We found her incredibly helpful and it was really interesting to go ‘behind the scenes’ at St Paul’s.

Thank you so much for taking the time to look Judith, very kind of you. It would be great to find some official evidence of him undertaking these duties. The Archives are my next step. Take care, kind regards, Paul.

Paul, pls email me re watch.

Fascinating article. Is there a list of fire watchers anywhere online? I am looking for Frederick Fortser and St Paul’s has been mentioned in the family oral history

My father Thomas Alpha Newby was in the St. Paul’s watch before he was called up in 1940. He was a professional singer – a Lay Vicar Choral in the St. Paul’s Cathedral Choir before and after the war.

a local got a medel think is name was george –lived in bow,i think he sold it