My next Open House location was reached after a short walk along the Thames Path, up Three Colt Street and left along Commercial Road to just before where the Commercial Road crosses the Limehouse Cut to find Limehouse Town Hall:

Limehouse Town Hall

Limehouse Town Hall from across the Commercial Road:

On the 12th June 1875, a small advert appeared on page 4 of the East London Advertiser:

“The Churchwardens and Overseers of the Parish of St. Anne, Limehouse, being desirous of erecting a new Town Hall and Parochial Offices, require a suitable site for the same in the Parish. Proposals for the Sale of Properties for this purpose may be addressed to the Churchwardens and Overseers at the temporary offices, 713 Commercial-road.”

The proposal for a new town hall was not universally popular in Limehouse. the letters page of the East London Observer reflect the views of some of the more vocal of the opponents including a Mr. Richardson who “did not like the expense of the Town Hall, or that it would be let for entertainments.”

A plot of land was purchased directly on the Commercial Road and next to St. Anne’s church however the letters of complaint kept coming. In June 1878, “T.M.” wrote to the editor of the East London Observer that, “having seen on the plot of ground, formerly Mr. Walter’s house, a board placed with the inscription ‘Site for Limehouse Town Hall’, it occurred that if you would kindly allow me through the medium of your paper to draw the attention of the authorities and inhabitants to the advantage of allowing the site to remain open, and in due course taking down the ugly coffee-shop adjoining, thereby prominently showing up one of Sir Christopher Wren’s noblest churches, and at the same time giving the authorities the means of widening the thoroughfare and facilitating public traffic in that busy part, it would be a great boon.”

Interesting that T.M. refers to the church as by Wren. It was designed by Wren’s assistant Nicholas Hawksmoor,

Despite these protests, Limehouse Town Hall was built with construction starting in 1879 and the hall being completed in 1881 at a cost of £10,000 plus £2,920 for the land.

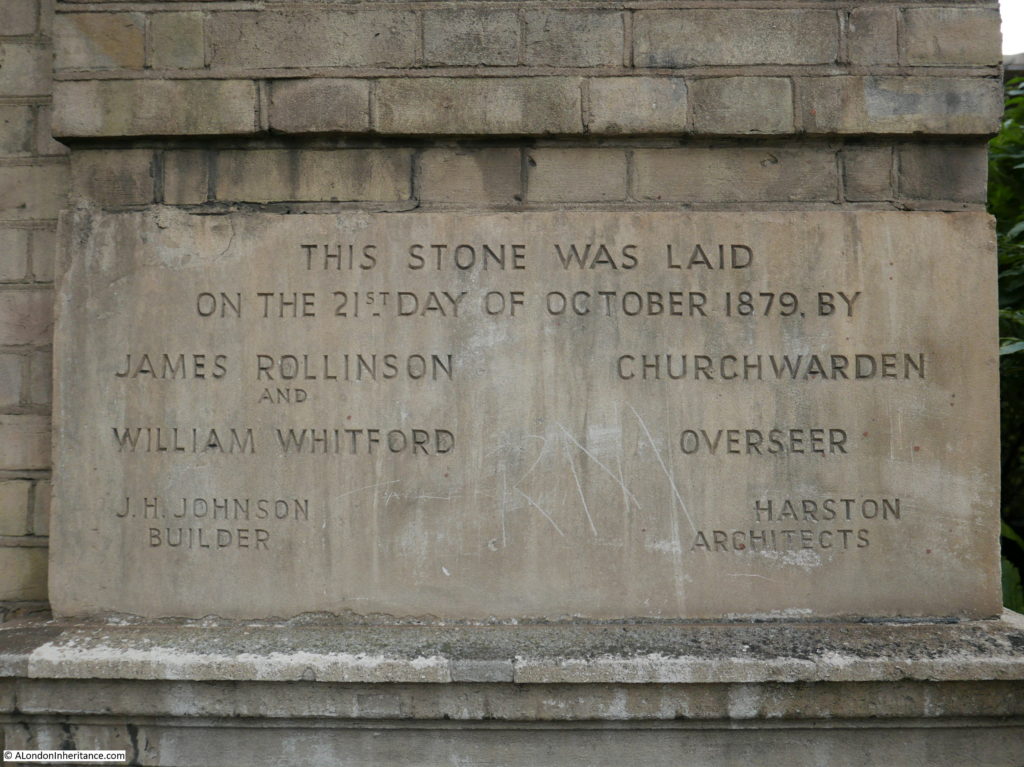

A foundation stone on the front of the building records the name of the builder and the architect.

The East London Observer on Saturday 2nd April 1881 reported on the opening of the new Limehouse Town Hall:

“LIMEHOUSE AND ITS NEW TOWN HALL – The parish of Limehouse has entered into possession of its new town hall, and the opening of the building has been the occasion of a considerable amount of celebration. The parish officials evidently felt that the event was one akin in importance to the transformation which takes place when the chrysalis is resolved into a beautiful winged butterfly, and they may accordingly be pardoned for displaying more or less ecstasy on the occasion. Hope of having a proper parochial habitation has with them been so deferred, that we have jocularly referred to the anticipated building for some years past as ‘the millennial town hall’. First of all there was the financial difficulty, and when this was conquered or arranged, there were tedious and trying legal delays which seemed to perpetually bar the way to the achievement of the object upon which the Vestry of Limehouse had set its mind. Delays, anticipations and doubts are now all dismissed, and the long-looked-for day of possession has arrived and has been jubilantly greeted.

The event of opening the new building was accompanied by much eclait, for the church wardens had the support and presence of both the members for Tower Hamlets, of Mr Samuda, the late representative of the borough – who, by the way, met with quite as warm a reception as either Mr. Bryee or Mr. Ritchie – of several of the county magistrates, and other gentlemen of local position and influence.

Naturally the entree into a building such as that erected at Limehouse is not an ordinary occurrence, and it will be admitted by those who witnessed the proceedings that all that could be done to vest the affair with extraordinary significance was done. This, of course, is quite a matter of taste, which it is not our intention to dispute. Still, as cool critics of facts, we must not overlook the circumstance that the possession of a town hall does not confer any addition of practical power. Limehouse for administrative purposes remains, as it was, part of the Limehouse District for sanitary purposes, and a part of the Stepney Union for poor-law purposes.”

The article then goes on to ask whether the new town hall may be part of a plan for Limehouse to gain more self-governing powers, but the article also challenges the expense of the new town hall if it was only to be used for “the self-glorification of the members of the Vestry and the exclusively for parochial purpose”, then there would be a challenge to the costs incurred.

They were confident that the Vestry would allow the free use of the new town hall by the rate payers of Limehouse, and that opportunities should be explored for letting the hall for public meetings, concerts etc. along with a reading room, free library and classes offering instruction in technical or higher education to help the people of Limehouse “might be cultivated morally and socially, and become better prepared to exercise their due influence upon the world of which they form part”.

The new Limehouse Town Hall did not therefore have an easy start and high expectations were set for how the building would be used.

The building has not functioned as a town hall for many years and has served many different uses over the years, including as the National Museum of Labour History which was opened in 1975 by Harold Wilson and lasted until the mid-1980s when financial troubles resulted in the closure of the museum with the collections being rescued by Manchester City council which formed the basis for the People’s History Museum.

Time to see the interior of the building.

On entering through the front doors, there is a short hall way to the bottom of the grand staircase which runs up to the first floor.

View from the staircase up to the first and second floors. The ornate balusters on the staircase and the second floor walkway are original, produced in Glasgow by the MacFarlane foundry.

Detail of the balusters – very ornate but they were not created specially for Limehouse Town Hall, they were a catalogue item of the foundry. I doubt those who criticised the costs of the town hall would have been happy with specially designed ornamentation for the building.

Looking down from the first floor landing.

Detail of the original tiles which have survived remarkably well.

The church of St. Anne Limehouse is just to the east of Limehouse Town Hall and there is a wonderful view of the church looking rather ethereal through the window half way up the staircase.

On the landing.

Limehouse Town Hall is now well over 100 years old and has been through a succession of owners over the years. The age of the building and impact on the fabric is clear at a number of locations within the building, including this view of the ceiling.

On the first floor is the large assembly room. It is this room that has served both the original Vestry and the people of Limehouse over the years. The hall has hosted numerous Vestry meetings, concerts, political meetings, dances, an infant welfare centre and exhibitions.

From 1881 the building was licensed for music and dancing and again in the pages of the East London Observer there is a report and a number of letters regarding the purchase of a piano for the hall, the cost of the piano and who was actually funding the purchase.

View of the other end of the assembly room. Until around 1950 there was a raised platform at this end of the hall which was used for speeches and performances.

Balcony over the main door leading from the landing. The glitter ball hints at one of the uses of the room.

A sign on the balcony provides a clue as to one of the previous uses of the hall.

Limehouse Town Hall was built with high expectations for its contribution to the lives of those living in Limehouse. Whilst Limehouse did not achieve the level of local governance to which the founders of the hall had aspired, the range of events held within the hall meant that it must have featured in the day-to-day lives of the people of Limehouse.

My next Open House visit was adjacent to Limehouse Town Hall and a very short walk to:

St. Anne’s Limehouse

The view of St. Anne’s Limehouse along St. Anne’s Passage.

St. Anne’s church was one of the twelve churches built as a result of a 1711 Act of Parliament to build churches in locations across London where populations had grown but were not well served by a local church.

A tax on coal was used to fund the building work, which resulted in a number of large and architecturally impressive churches across the city.

St. Anne’s was designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor and built between 1714 and 1727.

The church was badly damaged by fire in 1850 and also by bombing in 1941. It has been through a number of restorations, the latest having been completed in 2009.

I have walked past St. Anne’s many times, but have never seen inside. The last time I walked past was when I was exploring the sites at risk as identified by the Architects Journal in 1972 when the church was one of the sites of concern, although it was Grade I listed in 1950.

Walking into the church reveals a large and impressive interior.

With a very ornate roof.

Looking back towards the main entrance to the church. The organ was built by John Gray and Frederick Davison who had a factory in Euston Road.

The church was permitted by Queen Anne to fly the White Ensign and the location of the church, so close to the River Thames, together with the height of the church tower meant that St. Anne’s was a prominent landmark for those navigating the river and the church was marked by trinity House on navigation charts.

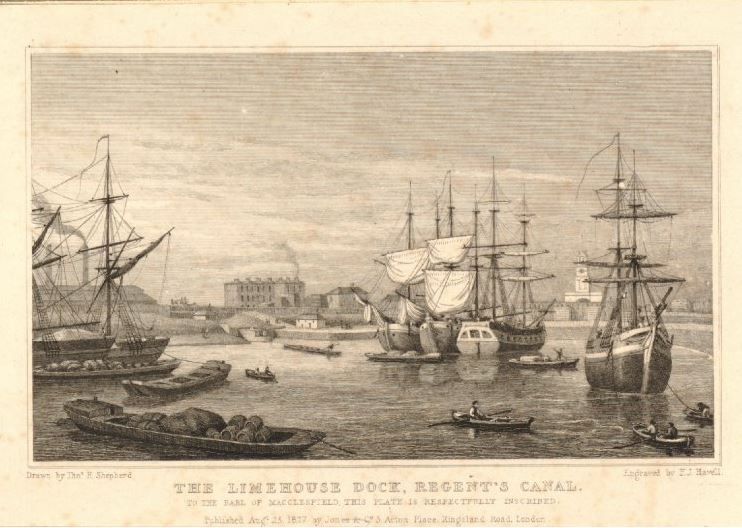

Many prints of the river around Limehouse show the church in the background. For example, the following print from 1827 shows the church as a very visible landmark just to the left of the ship on the right.

The White Ensign was originally the flag of the second most senior Admiral in the Navy. In 1864 the White Ensign became the ensign of the Royal Navy.

Display boxes in the church display naval flags including the flag of HMS Ark Royal and the White Ensign flown on the church:

The font which dates from the restoration carried out between 1851 and 1857 by John Morris and Philip Hardwick after the fire in 1850.

This fire appears to have almost destroyed the church. There was a report on the fire in the London Evening Standard on the 30th March 1850, titled “Total Destruction Of Limehouse Church By Fire”:

“We had the lamentable task yesterday of announcing the total destruction by fire of the beautiful parish church of St. Anne, Limehouse. We now append some further particulars:-

It appears that at seven o’clock yesterday morning a man named Wm. Rumbold, who lights the stove fires, and attending to the heating of the church, entered the edifice and proceeded with his duties. He ignited both the furnaces, and at a quarter past eight o’clock was about to satisfy himself of the degree of temperature in the interior of the church, when he perceived a strong smell of burning wood, and shortly afterwards saw a quantity of smoke issue from the roof. Impressed with a fear that something serious had happened, Rumbold ran off to the residence of Mr. George Coningham, the beadle and engine keeper of the parish, who resides about 150 yards distant from the church.

Coningham instantly returned with Rumbold to the church, on reaching which, Coningham ascended through the belfry and immediately opened a door over the organ loft leading to a vast chamber extending over the whole body of the church. As soon as the door was opened, Coningham and Rumbold were both driven back and nearly suffocated by a rush of smoke and rarefied air which issued out of this chamber, and clearly indicated where the seat of the mischief really was.

Coningham and Rumbold, with a view to rousing the neighbourhood, rang the two bells. An immense congregation of the inhabitants very speedily assembled. The fire had by this time begun to make its way through the roof. As yet there was no engine on the spot, and but a very scanty supply of water flowed from the street plugs.

The Rev. George Roberts, curate of the parish, who had by this time arrived. headed a large party of gentlemen, and by their exertions all the registers and other valuable parochial documents have been fortunately saved.

The progress of the flames was so rapid that not a little risk was incurred in this good work.

Several engines had arrived before the roof fell, and a very good supply of water was at length obtained, but from the great difficulty of getting at the spot where the fire raged, all the efforts of the firemen were comparatively fruitless, and Mr Braidwood, the leader of the force, at once pronounced that any hope of saving the interior of the church was quite out of the question.

The church was one of the most perfect interiors of the period in which it was built – Queen Anne’s time. It possessed a magnificent organ, built by Richard Bridge, in 1741, and a superb altar window of painted glass.”

It must have been devastating to the people of Limehouse to see their church in ruins.

Displayed in one of the side rooms is one of the hands from what may have been the original clock on the church. If I read the writing along the clock hand correctly it reads “This —– was taken from the face of the clock by R. Linton 1826”. The naval association of the church is shown in the clock hand by the anchor shape on the right of the hand.

There is also a memorial to those who I assume were parishioners who lost their lives in the First and Second World Wars.

It is always depressing to read these lists of names of those who had been killed during the wars, even more so when you find surnames repeated as you can imagine the impact it must have had on the families concerned.

One surname stood out on the St. Anne’s memorial – Peterken. There was an H.C. Peterken killed in the First World War and an A. Peterken killed in the Second World War.

I was able to find some background on H.C. Peterken.

Horace Peterken was a Private in the London regiment of the 2nd (City of London) Battalion (Royal Fusiliers). He was killed in action on the 26th October 1917. This was the first day of the Second Battle of Passchendale which ran until the 10th November 1917, so I assume he was killed on the first day of this battle.

In the 1911 Census he was living at 63 Three Colt Street in Limehouse (a street I walked up from the river to Commercial Street) along with his parents and six brothers and sisters.

His father, Henry George Peterken was 47 at the time of the census and is recorded as being born in Poplar. His father was a Letterpress Printer and Stationer. His mother, Sarah Ann Peterken was 46 and was born in Ratcliffe.

Sarah is recorded as having had 9 children, with 8 living and 1 died. Given that 7 children were living at the house in 1911 I assume the eighth may have been the oldest and had left home.

Horace was 15 at the time and his brothers and sisters living in Three Colt Street were; Ada, aged 23, Edith, aged 19, Winifred aged 17, Leonard aged 11, Mabel aged 9 and Cyril aged 4.

Ada was a Stationers Assistant so presumably worked for her father, Edith was a Dressmaker.

Henry George Peterken was a councillor and his printing shop was in Poplar High Street. The family may have been of Irish descent as on the 29th May 1909, the East London Observer reports that his daughter Winnie (Winifred) led the Irish detachment in a Pageant to celebrate Empire Day.

Horace was born in the last quarter of 1895, so was around 22 when he died at Passchendale.

In one corner of the church there are steps leading down to the crypt:

Walking down the stairs brings you to a smaller room before the main crypt which I suspect has the original flagstones across the floor.

The large crypt has been through a major restoration with some superb brickwork across the walls and roof.

Limehouse Town Hall and St. Anne’s Limehouse – two more fascinating buildings and each played their part in the rich history of East London.

Two more locations to visit which I will cover in my final post on Open House 2017 in the next couple of days.

Taking as a cue the line appearing above the 1827 print which ‘shows the church as a very visible landmark’, therein lies the clue to St Anne’s White Ensign and maritime association. The Red Ensign, the Merchant Navy’s official flag, has flown over the neighbouring St Dunstan and All Saints, Stepney, since 1620. The privilege had been granted by King James I in recognition of it being the ‘Church of the High Seas’, the first reached when sailing up the Thames and thus used to record any births, marriages and deaths on English-registered ships whilst at sea. At the time, the Red was the principal ensign of the Royal Navy which was organised into Red, White and Blue squadrons. As the borough grew eastward, St Anne’s in Limehouse, consecrated in 1780, became the first church reached by ships, Queen Anne granting it the right to fly permanently the White Ensign, the Red already taken. In 1864, the Royal Navy abolished the squadron structure and the Red Ensign became that of the Mercantile Marine. The Royal Navy adopted the White Ensign and the Blue was reserved for merchant ships under command of a Royal Naval Reserve officer. The three Ensigns have been displayed on the Cenotaph since its unveiling in 1919. They are joined by two Union Flags and a Royal Air Force Ensign which was added in 1943, twenty-five years after the RAF’s formation. Further afield, consider how many national flags are derived from the Red, White and Blue Ensigns.

As for the Red, it flies permanently elsewhere in the former Stepney, now Tower Hamlets. Tower Hill is the site of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s largest memorial in the UK in terms of the number commemorated, namely the Merchant Navy Memorial in Trinity Square Gardens. Its First and Second World Wars and Falklands Campaign sections bears the names of 36,102 members of the Mercantile Marine; Merchant Navy; Fishing Fleets; Lighthouse and Pilotage Authorities for whom there is no known grave. All are civilians: men and women, their ages range from 13 to 74. The First World War section alone bears 12,206 names of 103 nationalities. Two of those honoured, Captains Frederick Parslow and Archibald Smith of the Mercantile Marine, are the only civilians in the First World War to have been awarded the Victoria Cross while three others named were born at sea. In total, some 17,000 Mercantile Marine personnel and 2,417 ships were lost to enemy action during 1914-1918 together with 434 fishermen and 675 fishing vessels.

In 1928, the Mercantile Marine’s wartime service and sacrifice was recognised by HM King George V conferring upon it the present title of ‘Merchant Navy’. In the same year, the King instituted the appointment of Master of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets, one held now by HM The Queen.

A National Service of Commemoration for all who served in the Mercantile Marine and Fishing Fleets during the First World War will be held at 2.30pm on Tuesday, 17th October 2017. This will take place at the Merchant Navy Memorial in the presence of HRH The Princess Royal. The service will mark the centenary of the introduction of the convoy system in May 1917 which changed the outcome of the First World War, saving Britain from being starved in capitulation by late 1917. All are welcome.

Long may ‘A London Inheritance’ continue to illuminate Sundays.

I enjoy the way that in many of your pieces you enhance the description of the buildings by linking, and anchoring the buildings (Quite literally with St. Anne’s Limehouse) with the people and location in which they are situated.

Such a beautiful church. I was christened there in 1963 and went back recently to visit the area where I was born and lived until I was five. I visited the church but was unable to go inside so it was lovely to see the photographs and to hear more about the church’s history.

Nice bit of research and presentation. Love the rich stories that lurk not far from the surface wherever we go.

My GtGtGtGt grandfather a Thames Lighterman/shipwright and family, are buried there, lovely headstone monument still stands on the river side of the church, close to the church itself, and black stains on it may well have been from the fire.

I used to play marbles with my friend at the town hall when we were young and also play in st Ann’s church I lived in three colt Street and my friend lived in Newport street best times they were.

Thanks for composing such interesting and informative articles. My Gt Grandad was a Dustman living in Commercial Road acording to the 1891 census – all of his sons went to war and returned. I often go to this area to imagine what it would have been like in their day. You bring it back to life.

Thank you.

With great regret, I have to report that the National Service of Commemoration on Tuesday, 17th October 2017 mentioned at the end of my comment above has had to be cancelled. The closure of the road around Trinity Square had been requested for reasons of security and emergency vehicle access. The road is the joint responsibility of Tower Hamlets Council and the City of London Corporation; the former agreed with the request, the latter did not.

I have enjoyed your articles for a while, but have only now found this post mentioning my family.

You mention Horace Peterken, killed at Passchendale, whose name is seen on St Anne’s memorial. There is another Peterken whose name is there – Allan Peterken, killed in an air accident in 1944. Allan was just 20, and the son of Horace’s eldest brother George. He was training as a pilot, but had not yet been involved in any action.

There were four generations of Peterkens in the printing business, in Limehouse, Poplar and Canning Town, from 1836 to 1958. The business came to an end after a fire at the Poplar High Street works.

The family is likely to have Scottish roots rather than Irish, but there is no definite connection to either.

Thankyou