Finally, somewhat later than planned, here is the last post on my Open House 2017 visits. I had started in the Isle of Dogs and my final two locations were the Thames River Police Museum in Wapping and the Hermitage Moorings, a short distance further along the river towards St. Katherine Docks.

Thames River Police Museum

The Thames River Police Museum is usually only open by appointment so Open House provided the opportunity to just turn up and see this fascinating museum in one of the old workshops in what is still a working Police Station.

This is the front of the building on Wapping High Street. The museum is reached through the entrance on the left, through a small courtyard and up to the museum on the first floor of the part of the building facing the river.

The Marine Policing Unit as it is now named, is one of, if not the earliest uniformed police force in the world.

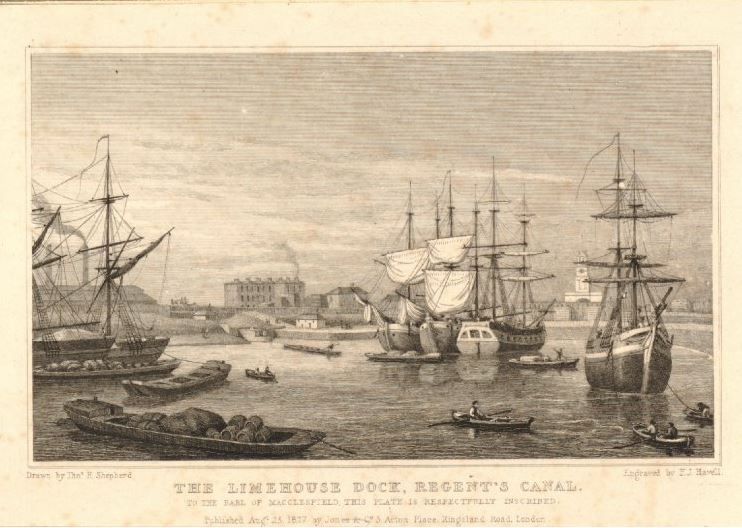

The Port of London was growing rapidly around Wapping in the last decades of the 18th century. There would be hundreds of different ships moored on the river, along the wharfs and warehouses facing the river and in the docks. The cargo stored in these shops and warehouses provided a ready source of income for those willing to steal or pilfer from these cargoes.

The problem was getting so bad that in the 1790s a uniformed police force was organised, approved by the government and funded by the various merchant companies that operated along the river.

The river police force was based at the location that remains their headquarters to this day. The first patrol of the river set out from this location in 1798.

In my father’s collection of photos, there are some of 1950’s era police river launches moored by Waterloo Bridge so I plan to write more about the history of the river police when I cover these photos in the coming months, so in the photos below is a brief view of what is a fascinating museum.

The museum is housed in a long, single room, at the end of which is a door facing onto the river.

The museum is a bit overwhelming at first sight as there is so much to look at. A couple of long display cases run part of the length of the room full with models, books, record books, old equipment used by the river police and much more. The walls are covered in drawings, paintings, photographs, maps and flags that tell the story of some of the significant events over the past two hundred years, and how the river police have evolved.

Display cabinets show some of the craft used by the river police. The original river patrols were made using rowing galleys, often with a crew of four comprising a Surveyor or Inspector and up to three Constables.

View of one narrow walkway showing how much there is to see in the museum.

Flags used on the patrol boats:

At the end of the museum is a door facing onto the river which provides some unique views.

Being an operational police station, there is a walkway leading down to a pier where some of the police boats are moored.

There is also a good view here across to Rotherhithe and down to the Isle of Dogs.

Half way along the walkway there is a traditional Police blue light:

The museum provides a fascinating view of the history of the Thames River Police, there is much to view and read. What makes this museum very special is that it is on the site where the original river police force was established and is within a building providing the same function to this day.

Back outside in the courtyard between the museum and the street there is a reminder that this is still a working river police station.

A short distance along Wapping High Street was my final Open House visit to:

Hermitage Moorings

In comparison with the other sites I visited during Open House, the Hermitage Moorings are very recent. The submission for planning permission was in 2004 and the Hermitage Moorings were constructed a few years later.

Despite being very recent, they are one of those many places around London that have a name that maintains a link with the location as it was many years ago.

The Hermitage Moorings can be found at the western end of Wapping High Street, just before the junction with St. Katherine’s Way.

The Hermitage Riverside Memorial Gardens run between Wapping High Street and the river, and at the eastern end of the gardens is the entrance to Hermitage Moorings.

Before taking a walk around the moorings, some history of the area and the name. In the extract from the 1896 Ordnance Survey map below, in the centre of the river’s edge is the Hermitage Steam Wharf. Just to the right of this wharf are Hermitage Stairs running down to a causeway into the river. It is here that the entrance to the Hermitage Moorings is located.

As can be seen from the map, the name Hermitage is used for a number of features – the stairs, the wharf and the basin.

You can also see on the left of the map the Red Lion Brewery, however according to “A Dictionary of London” published in 1918:

“Hermitage Brewhouse – A Brewhouse ‘so called of an hermite sometime being there,’ at the southern end of Nightingale lane, E. Smithfield” and “This hermitage seems to have given its name, not only to the Brewhouse, but to the Stairs and the Dock, etc.”

Nightingale Lane is the street running down from the top of the map to the left of Hermitage Basin down to the junction with Wapping High Street, so Hermitage Brewhouse may have been the earlier name of the brewery prior to Red Lion and it may have been named after a hermit.

Very tenuous but good to imagine that the new moorings are named after a hermit that lived close by.

The photo below from the Britain from Above website shows the area in 1946.

At the bottom right of the photo you can see some stairs and a causeway leading down into the river – this is the Union Stairs. Move along the water front to the left, pass the cranes and you will come to another causeway leading down into the river – this is the Hermitage Stairs.

The area between the Hermitage Stairs, the road behind and the river entrance to the basin is now the Hermitage Riverside Memorial Gardens.

The view across the gardens from the edge of the basin entrance looking across to where the entrance to the Hermitage Moorings is located in shown in the photo below.

The gardens are a memorial to the East London civilians who lost their lives, or were injured during the Second World War.

Time for a look at the moorings which were fully open during Open House weekend.

Hermitage Moorings were built, and are now owned and operated by Hermitage Community Moorings and they provide up to 23 berths for historic vessels with the owners living aboard. The moorings therefore form a community on the river rather than a place for distant owners to moor their boats.

When planning permission was applied for, there was general support for establishing a community on the river, however there were also a number of objections which appear to have come from the occupiers of the new apartments that had recently been built along the river.

Objections included that the moorings would be ‘blots on the landscape’ and ‘floating gypsy camps’ and that ‘rusting wrecks’ will be moored alongside the flats and the park.

The historic boats are very far from being rusting wrecks. The view looking downstream from the entrance to the moorings.

The view upstream towards Tower Bridge and the City.

There are two main pontoons extending either side from the centre of the moorings. All lined with a range of very well maintained historic boats. The majority with owners currently living aboard.

Some of the boats have potted gardens running along the edge of the pontoon.

Talking to some of the owners, there was a real pride in their boats, a very obvious community of people living on the river, and great pleasure in being able to live in such a way and location.

The boats are all extremely well maintained. many are Dutch, all have seen a working life of many decades and now rest at this wonderful location.

One of the differences between being on the river and walking the streets of the city is that from the river the wide sweep of the sky is visible and there is a connection between the river and weather which played such an important part in the lives of those who worked on the river for so many hundreds of years.

Names and numbers:

Despite the boats and owners living here at Hermitage Moorings, the boats are still in working order and able to make their way along the river. To have a mooring, the owner also needs a Day Skipper qualification as a minimum so the moorings are not simply providing a living place with a superb view – they are for those with the time and money to invest in maintaining a historic boat in working order and with the skill and qualifications to pilot those boats on the river.

Looking across towards Rotherhithe.

For Open House, there were also a couple of historic visitors to the Hermitage Moorings, including the Massey Shaw fireboat on the left.

There is a good view of the Hermitage Moorings from the riverside park and walkway along the river, however Open House provided the opportunity to walk among the boats and talk to the owners.

It was a fascinating day that demonstrated the sheer variety of sites open during Open House. From the pumping station on the Isle of Dogs, the Church and Town Hall at Limehouse, a museum in a working police station on the same location as where the river police force was formed, and river moorings from the last decade.

Hopefully, with some planning, I will get the whole weekend free for Open House 2018.