In 1979 I photographed the recently opened National Theatre on the Southbank:

In 2020 I photographed the same building again:

Before getting into the history of the building, the two photos highlight an issue I have with the Southbank – trees.

The trees along the Southbank illustrate a really difficult problem with landscaping public space. When walking along the Southbank, the trees add considerably to the environment. Providing shade, colour, breaking up and adding texture to an open space, as well as their environmental benefits.

However from an architectural perspective, I am not sure they are in the right place.

The National Theatre building has always been a rather controversial design. In 1988 the Prince of Wales described the theatre as “a clever way of building a nuclear power station in the middle of London without anyone objecting”, which is a rather good description.

Personally I really like the building. Close up, with the textured concrete, the external stairways and the diagonal columns that stretch out to support the lower cantilevered terrace. The building also looks good at night:

When the large glass windows to the lower floors, and the external stairways stand out well:

However it is only from a distance that the building can be really appreciated.

It was constructed on land next to the River Thames as part of the post war plan for cultural development of the Southbank, and it is from across the river that the overall design of the building can be fully seen.

Compare my two photos and standing on the north bank in 1979, we can see the complete façade of the building, the full width of the stacked terraces and the two rectangular concrete towers that rise above the building. In 2020 the trees obscure the majority of the tiered terraces.

The architect of the National Theatre building, Sir Denys Lasdun, probably designed the river facing façade expecting this view of the building to be seen from across the river, and the trees that have been planted along the Southbank obscure this view – as shown in my 2020 photo.

I am not against trees in a city environment. Far more are needed in London. They considerably improve the walking experience, they improve the environment, they cut down the wind tunnel effect produced by the clustering of tall buildings. I am just not sure that the trees along the Southbank are in the right place, in respect to the architecturally important buildings that line this part of the river.

We can see the same issue a short distance further west, where trees also obscure views of the Queen Elizabeth Hall complex to the left, and the Royal Festival Hall to the right.

The Royal Festival Hall also has a problem with the development around the Shell Centre tower, where the tower is the only remaining part of the original office complex. The earlier 9 storey office blocks surrounding the tower have been demolished, to be replaced by much taller blocks which dominate the view of the Royal Festival Hall from the east.

The National Theatre has a fascinating history.

Ideas for a National Theatre started in the mid 19th century, however first plans for a National Theatre would come fifty years later in 1903 when the actor and director Harvey Granville Barker published plans for a National Theatre.

Fund raising and campaigns continued through the first decades of the 20th century, however it would need the post war consensus that something good should come out of the war, along with the availability of space on a bomb damaged Southbank to turn almost one hundred years of ideas and campaigning into a physical building.

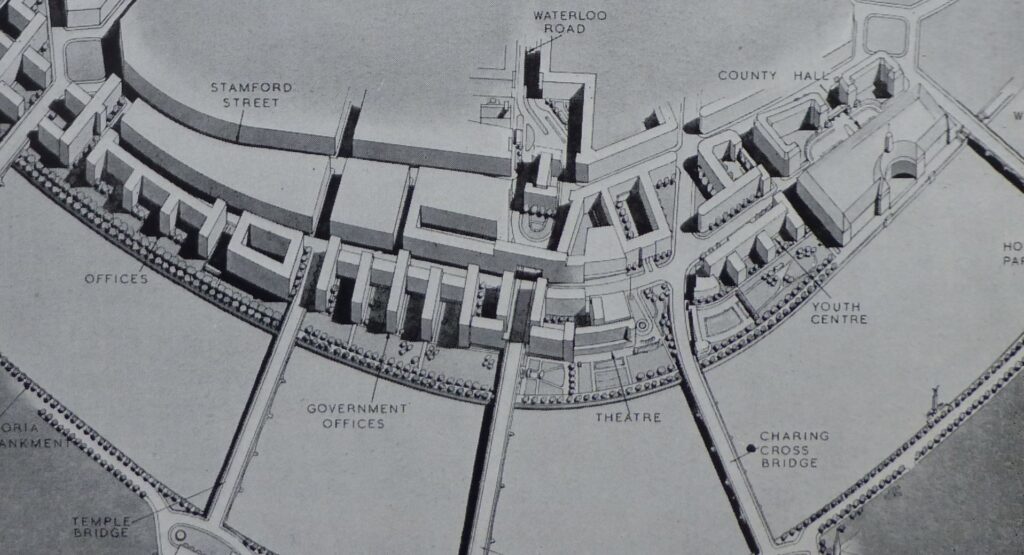

The 1943 County of London Plan proposed a radical development of the Southbank, with Government Offices, a Youth Centre, and in the centre, a Theatre.

The Festival of Britain went on to occupy the site and the Royal Festival Hall remained as the only permanent building from the festival. The Festival of Britain did not include a National Theatre.

In 1949 a National Theatre Bill committed £1M of central government funding towards the project, but the project would have to wait until 1961 when the London County Council committed to the rest of the funding for the theatre.

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) appointed a panel of architectural experts to evaluate proposals for the building’s design, and after a shortened evaluation process, Denys Lasdun was appointed as the architect for the National Theatre.

Denys Lasdun’s career started in the 1930s, but was interrupted during the Second World War by a period in the Royal Engineers.

Restarting his career after the war, his early work included east London developments such as Sulkin House and Keeling House (see this detailed exploration of these two buildings on the Municipal Dreams site).

In the early 1960s his work included the Royal College of Physicians in Regent’s Park, and the University of East Anglia campus, which included rather novel pyramidal shaped student halls.

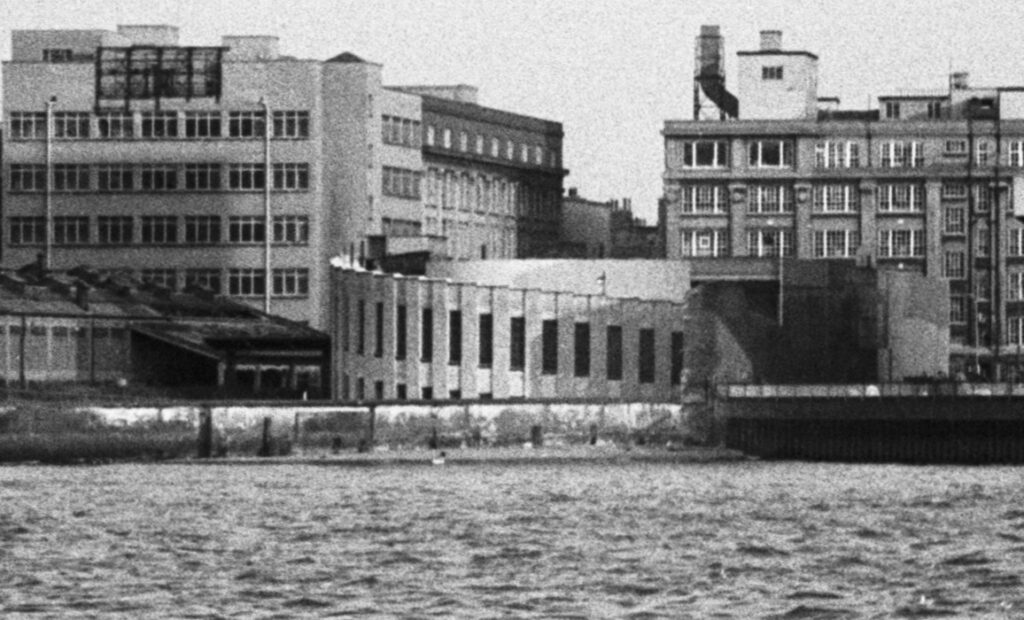

The initial plans for the National Theatre included not just the Theatre, but also an Opera House. Land was made available for these by the LCC, between County Hall and Hungerford Bridge. The land that had been occupied by the Dome of Discovery during the Festival of Britain.

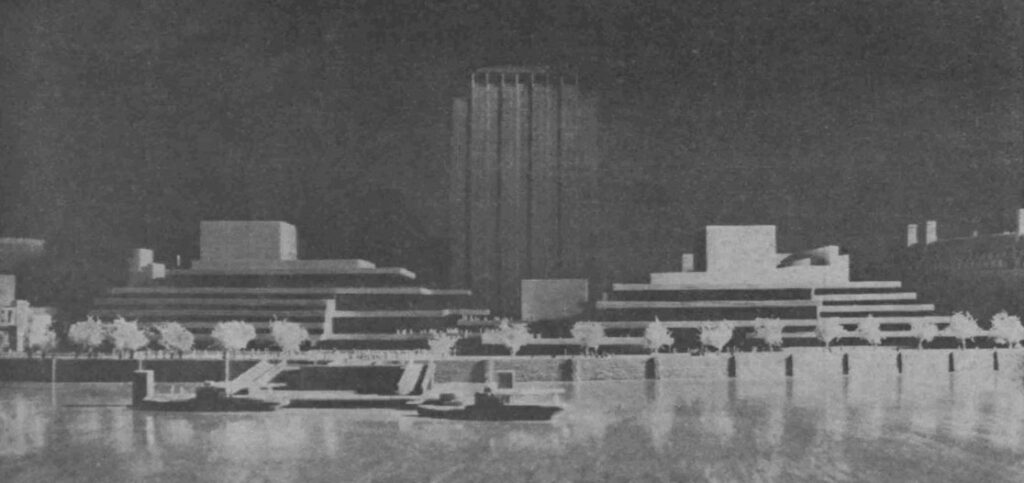

Lasdun created a model of his proposed National Theatre and Opera House in the original location. I photographed a photo of the model from a magazine a number of years ago (hence the poor quality). In the model below, the National Theatre is on the right and the Opera House is on the left. The ghostly form of the Shell Centre tower hovers in the background. The site today is occupied by the Jubilee Gardens (see this post for the story of the gardens).

The two buildings almost mirror each other, and the designs are very similar to that of the National Theatre we see today, with terraces running along the length of the buildings and the large concrete towers above.

They almost look like two cruise ships in dock alongside the river.

Going back to my comments earlier on trees, Lasdun’s model includes trees along the river side of the buildings, so it must have been part of his original thinking, however I wonder if he considered the visual impact these would have after years of growth on the visibility of his design from across the river?

The designs for the two buildings were highly regarded, however late 1960s budgetary constraints scaled back the project to just the National Theatre, along with a location change to a site immediately to the east of Waterloo Bridge.

Construction began in 1969.

Work during the 1970s was relatively slow due to a number of strikes, shortage of workers and the 1973 oil crisis. There were also funding problems, with the cost of the project going significantly over the initial budget. There had already been many design changes to address budgetary issues, for example, the terraces which run along the river facing side of the building were originally to have run around all sides of the buildings. Terraces on all but the river façade were dropped to save costs.

Additional funding was provided by the Arts Council and Government during the 1970s. In March 1975, Hugh Jenkins the Minister for the Arts made the following statement in Parliament in support of the National Theatre, in reply to a question “Our attitude to the arts has changed. We no longer take the view that only that which pays can and should be done. We now say that we must do it the best way it can be done. We must do it even if it is expensive because the theatre is as necessary to urban civilisation as an art gallery, a library, or a museum”.

As well as the National Theatre, the Government also had another costly project in view, the extension of the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden. With the planned move of the market to Nine Elms the Arts Council had already purchased the land, however Hugh Jenkins was not in a position to confirm any future plans or funding for the Royal Opera House.

Construction of the National Theatre was complicated not just with the building, but by the three theatres that were within the overall structure. These were planned to make use of the latest technological advances, which again caused delays and cost overruns.

The three theatres were:

- The Olivier. Named after Laurence Olivier, the first artistic director of the theatre. Seating 1160 in two main stepped tiers, linked by intermediate tiers

- The Lyttelton. Named after Oliver Lyttelton, the first chairman of the National Theatre. Seating 890 across two levels

- The Cottesloe. Named after Lord Cottesloe, the Chaiman of the Southbank Theatre Board. Seating between 200 and 400, dependent on the layout of stage and seating. The name of this theatre has since changed to the Dorfman, after Lloyd Dorfman, who donated £10 million towards the National Theatre Future redevelopment.

Each theatre had its own machinery to move scenery and equipment across the theatre, elevators to raise up to the stage floor, lighting and lighting control systems, sound systems and stage management systems. The Olivier also had an 11.5 metre drum revolving stage as part of the theatre’s construction.

The aim was to make each theatre as flexible as possible so as to support a wide range of future productions.

Attention to detail was not limited to the technically advanced theatres. Although the concrete construction of the building could appear to be a simple and cheap construction method, in reality great care was taken with the shuttering into which the concrete was poured. The wood used was sawn Douglas Fir, with a six-inch module being used for most parts of the building. This gives the building the appearance of being constructed from the concrete equivalent of wooden planks.

The Queen officially opened the National Theatre on the 25th October 1976, and the three individual theatres gradually opened between 1976 and 1977 as they were completed.

In five years time, the National Theatre will be celebrating 50 years since being opened by the Queen. The theatre has been redeveloped and upgraded during the past decades and still continues to serve the purpose first proposed in the mid 19th century.

Sir Denys Lasdun was knighted in 1976. He would continue with his architectural practice, with projects including the European Investment Bank in Luxembourg. He died in 2001.

I will leave the last word on the National Theatre to the architect Denys Lasdun who, when the theatre opened in 1976, said “Nothing takes priority over the atmosphere and the dramatic space created by the building. Although we’ve opened the theatre, it’s not the end but the beginning of something, from my point of view. The nature and the quality of something won’t be known for a couple of years; it depends on the directors and what they create within the new space”.

The building does indeed create an atmospheric and dramatic space.

Before closing the post, going back to the original 1979 photo, there is a mystery structure which I just cannot remember anything about. To the left of the National Theatre, on space which is now occupied by the IBM building, there is a strange, apparently circular structure which appears to spiral into or out of the ground.

I have enlarged this feature in the photo below:

Any suggestions would be most welcome.

The pyramidal residences at UEA were called the Ziggurat.

Very smart and futuristic in 1970 when I started in EUR.

Went back with friends in 2010 and time had not been kind to the concrete.

10 years on

perhaps they have smartened them up

Brilliant building trees need to go and the ugly added signage on said building claiming ‘Theatre’, seriously how stupid are people, it is a theatre we do not need a sign to say what it is so nor does the building, it knows what it is. I love your work by the way.

This is actually a digital pixel display, not a sign as such. It’s constantly moving and animated. It’s only noticeable from the other side of the river or if you break your neck in front of the Theatre.

The tree issue on the South Bank is well known. The saplings have as you say grown too large, yet no-one now would propose cutting them down. See also those obscuring the view to and from Somerset House. Re the Theatre; each of the stages is of a different type – prosecnium, in the round etc. – and the key to the shuttering is that planks in the same mould were planed to different thicknesses, more or less at random, so that the impression made on the concrete varies on depth as well as grain direction.

The curving thing is a car ramp, but to where I don’t know – a car park, one of those that sprage up post war?

I know it wasn’t in your brief but it is interesting to note that there was a chose site in South Kensington for the National Theatre before the war. It is the triangular site — which stood empty for many years — opposite the V&A. Harley Granville Barker and Bernard Shaw were involved in the choice of that site. Eventually the Ismaili Centre was built on the site. For many years there was a plaque nearby to commemorate the intention to build a National Theatre there, but I haven’t noticed it (or indeed bothered to look) for many years.

Your mystery building brought back vivid memories but with so much destructive building and rebuilding on the South Bank I hadn’t realised it had gone. I think it was part of a warehouse/storage facility which the innovative idea of a circular parking/access ramp, but I may be wrong – it’s a long time ago and some memories seem to be losing their accuracy.

Right with you re the trees.When walking along the Southbank there they add greatly to environment but your 1979 photo shows the building in all its original glory- an experience that is now lost to us. Shame the whole complex shown in the model was not built ,it would have looked fantastic.

Fascinating as always. May need some checking but my understanding is that the area as a whole is known as ‘the South Bank’, and ‘Southbank’ is only used in reference to the Southbank Centre.

The strange, apparently circular structure which appears to spiral into or out of the ground was a car-park !

Good morning another good article

With regards to the trees with the onset of global warming these will be very welcome as they will provide shade for people walking along the river bank trees and architecture should go hand-in-hand as both compliment each other sadly there is not enough trees in the city or Southbank planting the right trees it’s the most important element of thoughtful planning. David Ayres

It should not be forgotten that Prince Charles managed to wreak huge damage on the final years of Denys Lasdun’s practice in the UK with his sarcastic, damning view on the National Theatre. “Like everyone else, he’ll learn to like it” was still Lasdun’s response just a few years before he died. With hindsight, Lasdun was typically far too generous regarding the Prince’s intellect.

Another interesting and well-researched post from you. I see your point regarding the trees, lovely to walk under but quite an obstruction when viewed from the North bank. it will be interesting to see if they are replaced at the end of their lives. Here in Letchworth Garden city we have a similar obstruction blocking a wonderful view of the magnificent Arts and Crafts Spirella building (designed by Cecil Horace Hignett). The obstuction is a self seeded oak tree but the reaction to remove anything green in the Garden City is one of astonished horror! I get the same reaction when suggesting that the London Eye is a ‘carbuncle’ on the view of London’s wonderful County Hall. All in the eye of the beholder I suppose.

Wow – this has made me feel old. I first went to the NT in 1980 as a university student. I had NO idea it was so recently opened. When you’re twenty, even modern brutalist buildings seem to have been there for ever. And actually by 2020 they almost have!

I have mixed feelings on the trees. It is a shame not to see the full outline of the building. But on the other hand, the profile of the building rising above and mixed in with the trees is also a joy to my eye. In the same way that many Oxbridge colleges seem to have been able to integrate old buildings and modern brutalism in the 60s to the 80s with vegetation. On balance I’d settle for arguing for the status quo.

I was a regular visitor to the National Theatre before lockdown. The walk from Blackfrirs Station before and back after the show was always an added pleasure, with the varied views across the Thames and light show at night.. You don’t mention the inside of the building, and perhaps that wasn’t the architect’s first concern, as navigating one’s way from one part to another takes years of practice..

Behind your mystery building were the former London warehouse of HMSO and the Cornwall Press print works, one of which is now occupied by King’s College. Wonder if the circular building is a ramp up or down into one of those?

Your spiral structure is likely a multi storey car park?

You’re absolutely right about the trees!

…one could argue that before humans turned up in London trees would have been there …and we thought nothing of uprooting them to build. trees are by far more important than some “view”

Leaf green is such a naff colour…..do you have any recent bare winter shots (perhaps in black and white)?

This link to Alamy gives another view of the spiral structure you ask about:

https://www.alamy.com/high-shot-taken-in-1978-of-londons-south-bank-showing-both-sides-of-the-river-thames-waterloo-bridge-south-bank-television-centre-part-of-the-national-theatre-image243223059.html?pv=1&stamp=2&imageid=065377BE-3FC3-469F-9725-E2E15AFB2721&p=817247&n=0&orientation=0&pn=1&searchtype=0&IsFromSearch=1&srch=foo%3dbar%26st%3d0%26pn%3d1%26ps%3d100%26sortby%3d2%26resultview%3dsortbyPopular%26npgs%3d0%26qt%3dlondons%2520south%2520bank%2520in%25201970s%26qt_raw%3dlondons%2520south%2520bank%2520in%25201970s%26lic%3d3%26mr%3d0%26pr%3d0%26ot%3d0%26creative%3d%26ag%3d0%26hc%3d0%26pc%3d%26blackwhite%3d%26cutout%3d%26tbar%3d1%26et%3d0x000000000000000000000%26vp%3d0%26loc%3d0%26imgt%3d0%26dtfr%3d%26dtto%3d%26size%3d0xFF%26archive%3d1%26groupid%3d%26pseudoid%3d%26a%3d%26cdid%3d%26cdsrt%3d%26name%3d%26qn%3d%26apalib%3d%26apalic%3d%26lightbox%3d%26gname%3d%26gtype%3d%26xstx%3d0%26simid%3d%26saveQry%3d%26editorial%3d1%26nu%3d%26t%3d%26edoptin%3d%26customgeoip%3d%26cap%3d1%26cbstore%3d1%26vd%3d0%26lb%3d%26fi%3d2%26edrf%3d%26ispremium%3d1%26flip%3d0%26pl%3d

This appears to show another view of the structure:

https://media.gettyimages.com/photos/festival-of-britain-site-south-bank-lambeth-london-april-1951-the-picture-id918904628

To the left of the chimney appears to be the mystery structure:

https://www.alamy.com/festival-of-britain-image7128556.html

Very good morning to you. Thank you for your continuing posts on this excellent website, its absolutely fascinating, and I cant wait for each new installment!

With regards the peculiar drum shaped building left adjacent the National Theatre, I’ve done some digging, and it appears to be nothing more exciting than a oddly designed carpark.

https://www.architecture.com/image-library/ribapix/gallery-product/poster/national-theatre-south-bank-london/posterid/RIBA88120.html

Now inhabited by the IBM building (recently listed).

I hope this helps!

Several people have already replied that the circular building is a ramp up to the roof and I concur. Interestingly, in the following aerial photograph from 1949 it appears to have been used as some kind of rooftop storage facility: https://britainfromabove.org.uk/en/image/EAW025715

Look forward to the day it all opens up again.

your next article mentions “The building partly visible behind this structure was the London warehouse of HMSO ………..”. This was called “Cornwall House”, with the HMSO on at least the ground floor from what I can remember and the remainder was the home of The Laboratory of the Government Chemist. The latter being part of the Dept of Trade & Industry, at least it was back in the mid-1970s when I worked there for a year. Its origins can be traced back to 1842 when the Laboratory of the Board of Excise was founded in the City of London to regulate the adulteration of tobacco until 1875 when the laboratory was appointed ‘referee analyst’ under the new Sale of Food and Drugs Act. From then to now they host the unique function of the ‘Government Chemist’, providing expert opinion, based on independent chemical and bioanalytical measurement, to help avoid or resolve disputes pertaining to food and agriculture, and we give advice to Government and the wider community dependent on analytical science. As part of past Government ideas of decentralising various departments, the LGC was destined to potentially move to Whitehaven in Cumbria in the 1970s. However, the LGC did move into new premises but these were built on Government-owned land next to the national Physical Laboratory at Teddington in Surrey in about 1990/91 (I did get invited back to the opening). In 1996 it was privatised and renamed LGC (the acronym that it had always been referred to prior to that). The LGC has grown immensely and has numerous locations around the world.

A further comment to the intriguing ‘car park’ to the east of the National Theatre. The building shape is clearly identified on the 1951 edition of the Ordnance Survey 1:2500 map, and the RAF aerial survey of 1949 shows the ramp and again the distinctive curved shape. The site is the western edge of the Shot Tower Wharf which by the 1970s was being used , together with the adjoining Commercial Wharf by The Daily Mail as a printing and distribution centre. It appears on the edge of one of my photos from 1977, but was clearly not interesting enough (as least from ground level ) for me to take any additional images. My photos show that it was demolished in early 1980, and by 1981 the IBM building replaced it.

In reviewing my own images it is also interesting to note how much of the foreshore was reclaimed from the river to construct the (later named) Jubilee walkway from Waterloo Bridge to the Oxo Tower.

A theatre is meant to serve not just the audience, but the people who work in the building as well. I cannot speak for other departments, but the The Olivier auditorium is one of the driest interiors I ‘ve ever worked in. Not acoustically, in terms of moisture, and it’s all down to the concrete. When I first heard this, I was surprised, it’s next door to the Thames, but it’s true. Anyone acting in that space needs water bottles placed at every available exit or entrance. My favourite thing about the building was the fact that the dressing room windows look onto an interior space. On Press Nights , the other companies would bang on the windows at Beginners, to show support for those about to face the critics.