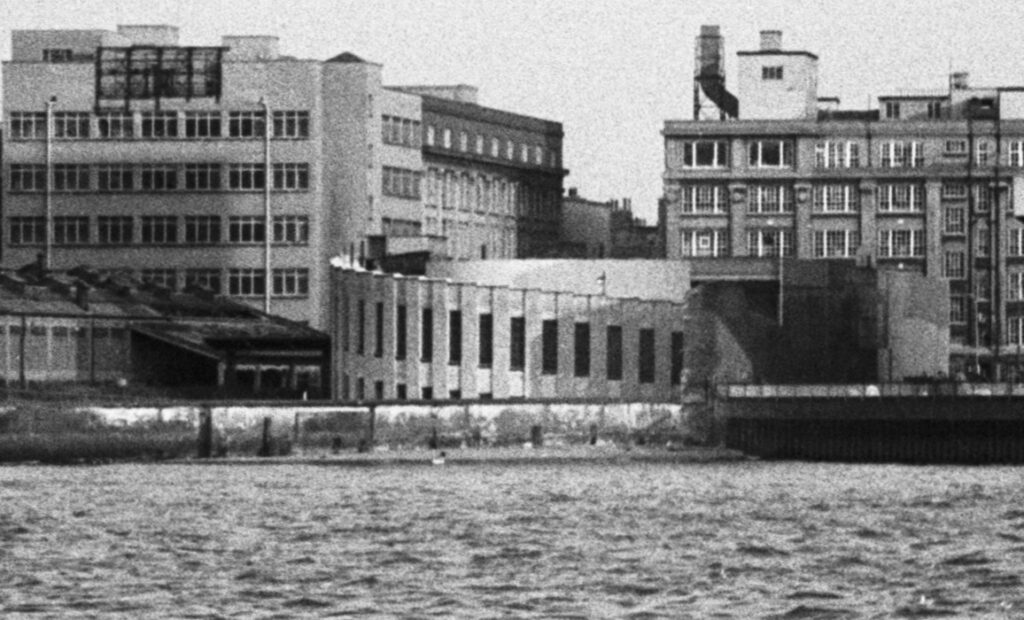

In 1979 I photographed the recently opened National Theatre on the Southbank:

In 2020 I photographed the same building again:

Before getting into the history of the building, the two photos highlight an issue I have with the Southbank – trees.

The trees along the Southbank illustrate a really difficult problem with landscaping public space. When walking along the Southbank, the trees add considerably to the environment. Providing shade, colour, breaking up and adding texture to an open space, as well as their environmental benefits.

However from an architectural perspective, I am not sure they are in the right place.

The National Theatre building has always been a rather controversial design. In 1988 the Prince of Wales described the theatre as “a clever way of building a nuclear power station in the middle of London without anyone objecting”, which is a rather good description.

Personally I really like the building. Close up, with the textured concrete, the external stairways and the diagonal columns that stretch out to support the lower cantilevered terrace. The building also looks good at night:

When the large glass windows to the lower floors, and the external stairways stand out well:

However it is only from a distance that the building can be really appreciated.

It was constructed on land next to the River Thames as part of the post war plan for cultural development of the Southbank, and it is from across the river that the overall design of the building can be fully seen.

Compare my two photos and standing on the north bank in 1979, we can see the complete façade of the building, the full width of the stacked terraces and the two rectangular concrete towers that rise above the building. In 2020 the trees obscure the majority of the tiered terraces.

The architect of the National Theatre building, Sir Denys Lasdun, probably designed the river facing façade expecting this view of the building to be seen from across the river, and the trees that have been planted along the Southbank obscure this view – as shown in my 2020 photo.

I am not against trees in a city environment. Far more are needed in London. They considerably improve the walking experience, they improve the environment, they cut down the wind tunnel effect produced by the clustering of tall buildings. I am just not sure that the trees along the Southbank are in the right place, in respect to the architecturally important buildings that line this part of the river.

We can see the same issue a short distance further west, where trees also obscure views of the Queen Elizabeth Hall complex to the left, and the Royal Festival Hall to the right.

The Royal Festival Hall also has a problem with the development around the Shell Centre tower, where the tower is the only remaining part of the original office complex. The earlier 9 storey office blocks surrounding the tower have been demolished, to be replaced by much taller blocks which dominate the view of the Royal Festival Hall from the east.

The National Theatre has a fascinating history.

Ideas for a National Theatre started in the mid 19th century, however first plans for a National Theatre would come fifty years later in 1903 when the actor and director Harvey Granville Barker published plans for a National Theatre.

Fund raising and campaigns continued through the first decades of the 20th century, however it would need the post war consensus that something good should come out of the war, along with the availability of space on a bomb damaged Southbank to turn almost one hundred years of ideas and campaigning into a physical building.

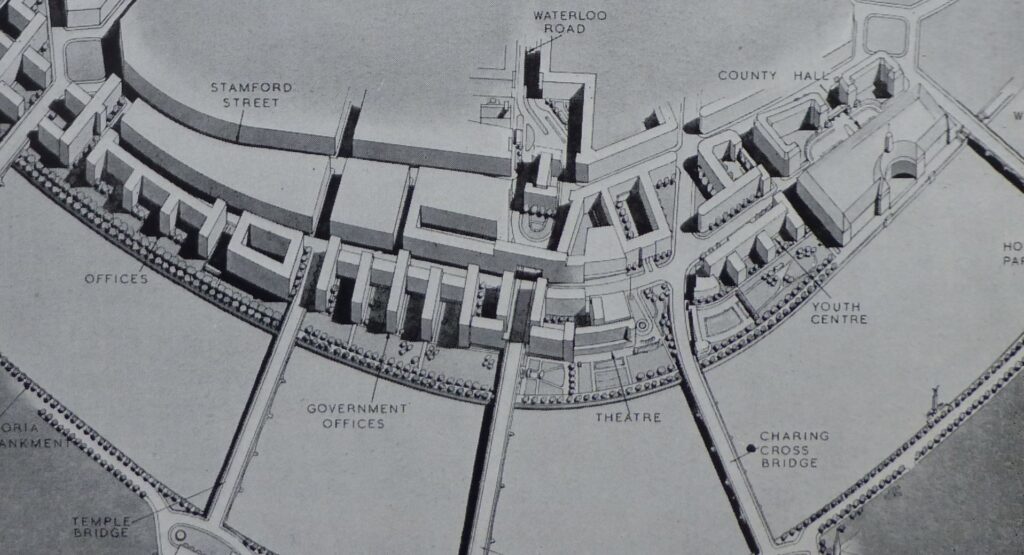

The 1943 County of London Plan proposed a radical development of the Southbank, with Government Offices, a Youth Centre, and in the centre, a Theatre.

The Festival of Britain went on to occupy the site and the Royal Festival Hall remained as the only permanent building from the festival. The Festival of Britain did not include a National Theatre.

In 1949 a National Theatre Bill committed £1M of central government funding towards the project, but the project would have to wait until 1961 when the London County Council committed to the rest of the funding for the theatre.

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) appointed a panel of architectural experts to evaluate proposals for the building’s design, and after a shortened evaluation process, Denys Lasdun was appointed as the architect for the National Theatre.

Denys Lasdun’s career started in the 1930s, but was interrupted during the Second World War by a period in the Royal Engineers.

Restarting his career after the war, his early work included east London developments such as Sulkin House and Keeling House (see this detailed exploration of these two buildings on the Municipal Dreams site).

In the early 1960s his work included the Royal College of Physicians in Regent’s Park, and the University of East Anglia campus, which included rather novel pyramidal shaped student halls.

The initial plans for the National Theatre included not just the Theatre, but also an Opera House. Land was made available for these by the LCC, between County Hall and Hungerford Bridge. The land that had been occupied by the Dome of Discovery during the Festival of Britain.

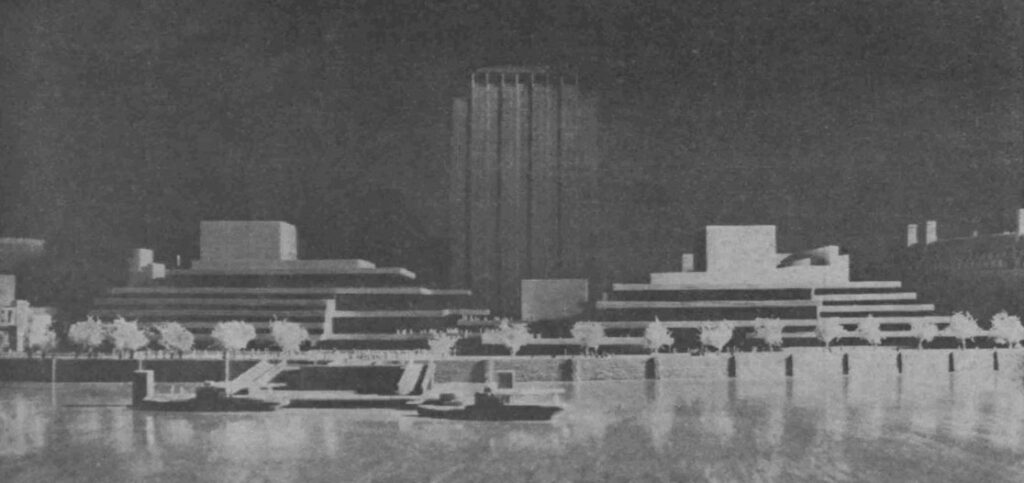

Lasdun created a model of his proposed National Theatre and Opera House in the original location. I photographed a photo of the model from a magazine a number of years ago (hence the poor quality). In the model below, the National Theatre is on the right and the Opera House is on the left. The ghostly form of the Shell Centre tower hovers in the background. The site today is occupied by the Jubilee Gardens (see this post for the story of the gardens).

The two buildings almost mirror each other, and the designs are very similar to that of the National Theatre we see today, with terraces running along the length of the buildings and the large concrete towers above.

They almost look like two cruise ships in dock alongside the river.

Going back to my comments earlier on trees, Lasdun’s model includes trees along the river side of the buildings, so it must have been part of his original thinking, however I wonder if he considered the visual impact these would have after years of growth on the visibility of his design from across the river?

The designs for the two buildings were highly regarded, however late 1960s budgetary constraints scaled back the project to just the National Theatre, along with a location change to a site immediately to the east of Waterloo Bridge.

Construction began in 1969.

Work during the 1970s was relatively slow due to a number of strikes, shortage of workers and the 1973 oil crisis. There were also funding problems, with the cost of the project going significantly over the initial budget. There had already been many design changes to address budgetary issues, for example, the terraces which run along the river facing side of the building were originally to have run around all sides of the buildings. Terraces on all but the river façade were dropped to save costs.

Additional funding was provided by the Arts Council and Government during the 1970s. In March 1975, Hugh Jenkins the Minister for the Arts made the following statement in Parliament in support of the National Theatre, in reply to a question “Our attitude to the arts has changed. We no longer take the view that only that which pays can and should be done. We now say that we must do it the best way it can be done. We must do it even if it is expensive because the theatre is as necessary to urban civilisation as an art gallery, a library, or a museum”.

As well as the National Theatre, the Government also had another costly project in view, the extension of the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden. With the planned move of the market to Nine Elms the Arts Council had already purchased the land, however Hugh Jenkins was not in a position to confirm any future plans or funding for the Royal Opera House.

Construction of the National Theatre was complicated not just with the building, but by the three theatres that were within the overall structure. These were planned to make use of the latest technological advances, which again caused delays and cost overruns.

The three theatres were:

- The Olivier. Named after Laurence Olivier, the first artistic director of the theatre. Seating 1160 in two main stepped tiers, linked by intermediate tiers

- The Lyttelton. Named after Oliver Lyttelton, the first chairman of the National Theatre. Seating 890 across two levels

- The Cottesloe. Named after Lord Cottesloe, the Chaiman of the Southbank Theatre Board. Seating between 200 and 400, dependent on the layout of stage and seating. The name of this theatre has since changed to the Dorfman, after Lloyd Dorfman, who donated £10 million towards the National Theatre Future redevelopment.

Each theatre had its own machinery to move scenery and equipment across the theatre, elevators to raise up to the stage floor, lighting and lighting control systems, sound systems and stage management systems. The Olivier also had an 11.5 metre drum revolving stage as part of the theatre’s construction.

The aim was to make each theatre as flexible as possible so as to support a wide range of future productions.

Attention to detail was not limited to the technically advanced theatres. Although the concrete construction of the building could appear to be a simple and cheap construction method, in reality great care was taken with the shuttering into which the concrete was poured. The wood used was sawn Douglas Fir, with a six-inch module being used for most parts of the building. This gives the building the appearance of being constructed from the concrete equivalent of wooden planks.

The Queen officially opened the National Theatre on the 25th October 1976, and the three individual theatres gradually opened between 1976 and 1977 as they were completed.

In five years time, the National Theatre will be celebrating 50 years since being opened by the Queen. The theatre has been redeveloped and upgraded during the past decades and still continues to serve the purpose first proposed in the mid 19th century.

Sir Denys Lasdun was knighted in 1976. He would continue with his architectural practice, with projects including the European Investment Bank in Luxembourg. He died in 2001.

I will leave the last word on the National Theatre to the architect Denys Lasdun who, when the theatre opened in 1976, said “Nothing takes priority over the atmosphere and the dramatic space created by the building. Although we’ve opened the theatre, it’s not the end but the beginning of something, from my point of view. The nature and the quality of something won’t be known for a couple of years; it depends on the directors and what they create within the new space”.

The building does indeed create an atmospheric and dramatic space.

Before closing the post, going back to the original 1979 photo, there is a mystery structure which I just cannot remember anything about. To the left of the National Theatre, on space which is now occupied by the IBM building, there is a strange, apparently circular structure which appears to spiral into or out of the ground.

I have enlarged this feature in the photo below:

Any suggestions would be most welcome.