A few months ago I started a series of posts following the sites that were identified as at risk in an Architects’ Journal article written in January 1972. This was a point in time when East London had been through a period of post war decline, and the changes that have developed East London to the area we see today could just be seen on the horizon.

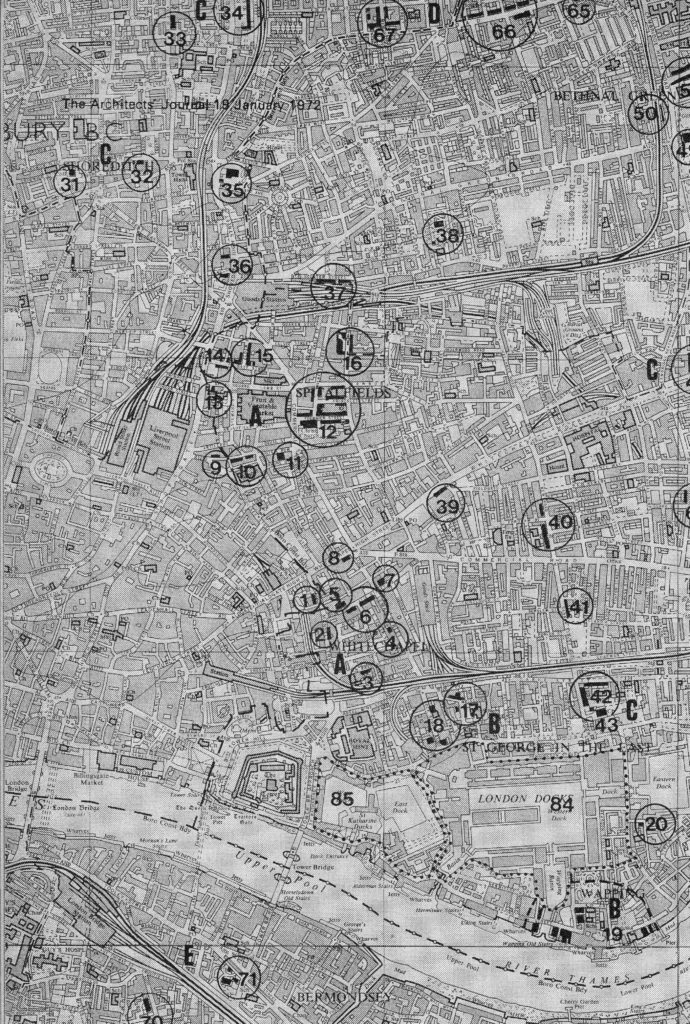

A key focus of the article was a concern that should there be comprehensive development of the area in the coming years, then a range of pre-1800 buildings should be preserved. The article included a map that identified 85 locations where there are either individual or groups of buildings that should be preserved. The area includes parts of south London, although still to the east of the central city area, therefore considered as being east London.

The 85 locations were divided into different categories based on how the locality had developed. I have already written about the Category A sites, and part of Category B. For this week’s post I am starting on the Category C sites which the Architects’ Journal classified as “Medieval village centres”. The article describes these as:

“Inland villages grew more slowly than those on the ‘industrial’ riverside. They remained a series of basically rural communities, with a heavy smattering of rich Londoners’ country retreats until London’s great expansion in the early 19th century. However this countryside, even in the 17th and 18th centuries, was not totally unaffected by its proximity to the City whose dwellers used it for relaxation – Hoxton in the 17th century was a popular fresh air resort and Pepys would walk there across fields from Seething Lane – and also exploited it for industrial purposes. Hanway wrote in 1767: ‘we have taken plans to render its (London’s) environs displeasing both to sight and smell. The chain of brick-kilns that surround us, like the scars of smallpox, makes us lament the ravages of beauty and the diminution of infant ailment'”.

An extract of the map from the article is shown below. For this post I will be walking from site 31 in Shoreditch to site 36 with a detour via Hoxton, covering the sites listed in the Architects’ Journal along with a few of the features I found whilst walking in this fascinating area of East London.

Site 31 – 1725 House In Charles Square, Shoreditch

I walked to Charles Square from Old Street station, with the square being found just north of the junction of Old Street and Great Eastern Street. A small park in the centre of the square is surrounded on all sides with post war housing, however the 1725 house identified in the article stands out clearly.

In 1972 this was the view across the square to the house:

I could not take a similar photo as the trees were in leaf and they obscured the view of the house so I had to get closer, however the house looks much the same today (including the buildings on either side).

The house in Charles Square is a remnant of attempts in the late 17th and early 18th centuries to start a West End type of development that would attract rich City merchants. The house is a very different architectural style to the rest of the buildings that line the sides of the square, however all the later buildings are of roughly the same height as the 1725 house which helps the different styles to integrate.

Leaving Charles Square I headed to the next site in Hoxton Square, firstly crossing Pitfield Street where on the corner with Coronet Street is one of the many old Truman’s pubs that can be found across London. This is “The Hop Pole”. Closed in 1985 and now converted into flats.

Coronet Street leads into a large open area bounded by Coronet Street and Boot Street. At one end is a large brick building that is now the home for the National Centre for Circus Arts:

However originally this was an electricity generating station for the Vestry of St. Leonard Shoreditch. The building dates from 1896, a time when electricity generation was mainly the responsibility of the individual Vestries across London who constructed generation stations to serve the growing electricity requirements of their local area.

The original function of the building is still recorded above the main entrance.

The plaque on the building records that the generating station burnt rubbish to create the steam needed to generate electricity. This was a rather unique power source at the time as the majority of other London electricity generating stations burnt coal.

The Shoreditch Electricity Generating Station operated until 1940 then post war developments with the national grid and construction of large power stations meant that this type of local station was redundant.

The building was derelict for some years, but today, as well as the Circus Arts school, the building is also an event venue for hire with the large rooms needed to house the original equipment providing the perfect space for the uses to which the building is now put.

As well as the National Centre for Circus Arts, the square has a statue of a “Juggling Figure” by Simon Stringer, created to “Commemorate the traditions of Theatre and Music Hall in Hoxton and Shoreditch”

From Coronet Street, it was a very short walk to my next location:

32 – A Few Late 17th Century Relics In Hoxton Square

The text is not specific as to where these “relics” can be found in Hoxton Square, however the map shows a black marker at the location on the south western corner of the square where Hoxton Square connects to Coronet Street.

At this location I found the following single building which looks to be of around the right date.

Hoxton Square is a fascinating area that deserves a dedicated post to cover the history of the area. The central garden was laid out in 1709 and the surrounding housing was largely finished by 1720. Although the Architects’ Journal shows the building(s) at a different location, it may just be a mapping error as probably the oldest remaining building on the square is number 32, on the eastern side of the square, probably dating from around 1690. This is the building on the right in the photo below:

Hoxton Square has a variety of buildings of different ages and architectural styles as shown in the following photos:

Walking around Hoxton Square, it is possible to trace how the square has developed from the earliest buildings at the end of the 17th century, when the square was mainly residential, as industry such as furniture making took over many of the buildings, the construction of St Monica’s Catholic Church in 1865 (on the right in the above photo) to serve the poor local Irish population through to the present day.

I could have stayed in Hoxton Square for some time, and I will write further on this fascinating area in the future, however I had many other sites on the map to walk to.

The next location was in Hoxton Street, where firstly I found the following crest of the London County Council on the side of Follingham Court. I love finding these as they are a reminder of a time when London housing was being built for Londoners as genuinely affordable, rather than the so called luxury apartments that now take over almost any available plot of land, or disused building.

The Macbeth – thankfully still a music venue as locations such as these seem to be disappearing from London’s streets.

I was not expecting to see the following plaque on the side of a recent building at the junction of Hoxton Street and Crondall Street:

William Parker, Lord Monteagle had a house here in Hoxton and it was here that he received the letter revealing the details of the gunpowder plot.

The opposite corner of Crondall Street – these are the types of buildings and food outlets that I will always associate with Hoxton.

Site 33 – Early 18th Century Pair

Based on the map in the Architect’s Journal, I believe that the buildings shown in the photo below are the early 18th Century pair.

I assume that when built, these buildings were set back from Hoxton Street with perhaps an ornamental garden between house and street, or given that the other two, much lower status, buildings on the right are also set back from the street, this may have been a small square set back from the road. The 1893 Ordnance Survey map does not help as it shows two buildings set back, one of which (on the left) also has a building extending to the street.

There is also no photo in the Architects’ Journal showing these buildings in 1972 so difficult to tell how long they have been sealed off from Hoxton Street in this manner. A shame that these buildings are hidden in this way.

Also in Hoxton Street – Hayes and English – funeral directors since 1817:

F. Cooke pie and mash shop, the family business started in 1862 by Robert Cooke in Sclater Street.

Leaving Hoxton Street, I walked down Falkirk Street to Kingsland Road to find:

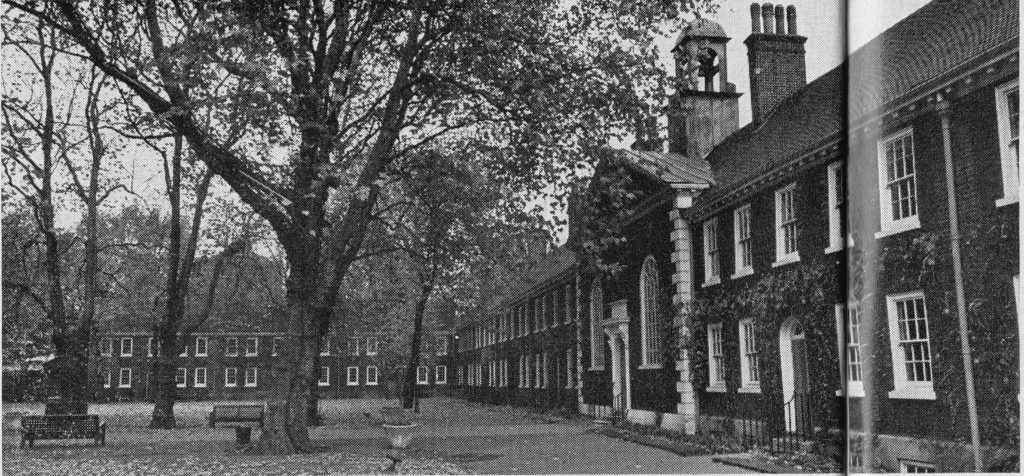

Site 34 – Geffrye Almshouses

The Geffrye Almshouses, or as they are better known today as the Geffrye Museum look much the same today:

As they did in the 1972 Architects’ Journal article:

The Geffrye Museum was originally built as almshouses for the Ironmongers’ Company in 1715. Early in the 20th century, the Ironmongers’ Company moved their almshouses out of Hoxton and there was a serious risk in 1913 that the buildings could have been demolished.

Purchased by the London County Council, they were converted into a museum and are now run by the Geffrye Museum Trust.

I am surprised that the Geffrye Almshouses were included in the Architects’ Journal list as their definition of sites to be included was “buildings that should be considered for preservation if comprehensive redevelopment of East London were undertaken.” Even in 1972, and with the buildings in apparently good condition, I would have thought that there would be no question that these buildings would be preserved.

The article did use the Geffrye Museum as an example of how “Learning and Looking” could be distributed across London, rather than in the overcrowded museums and art galleries in west and central London, The article comments that:

“Indeed it is a matter for astonishment that museums run on the lines of the Geffrye Museum in Kingsland Road, London, E13, are not a recognised part of our education system in every city. As a result of the Geffrye’s aim of interesting and involving children, all sorts of stimulating knowledge-hunts are provided there. As a result it has the unique distinction among museums of having sometimes had to close its doors on Saturdays, declaring ‘ house full’ because the children pour into it in such crowds.

There seems to be absolutely no serious reason why our great museums and art galleries should not establish new branches, colonising – if you like – such regions as east London, by siting their much needed expansions in that area. This would be good not only for those who live there, and above all their children, it would also bring a number of tourists into this half of London with all the advantages already discussed here, including that of relieving the summer congestion in the West End.”

A sensible aim which unfortunately did not progress any further than the article.

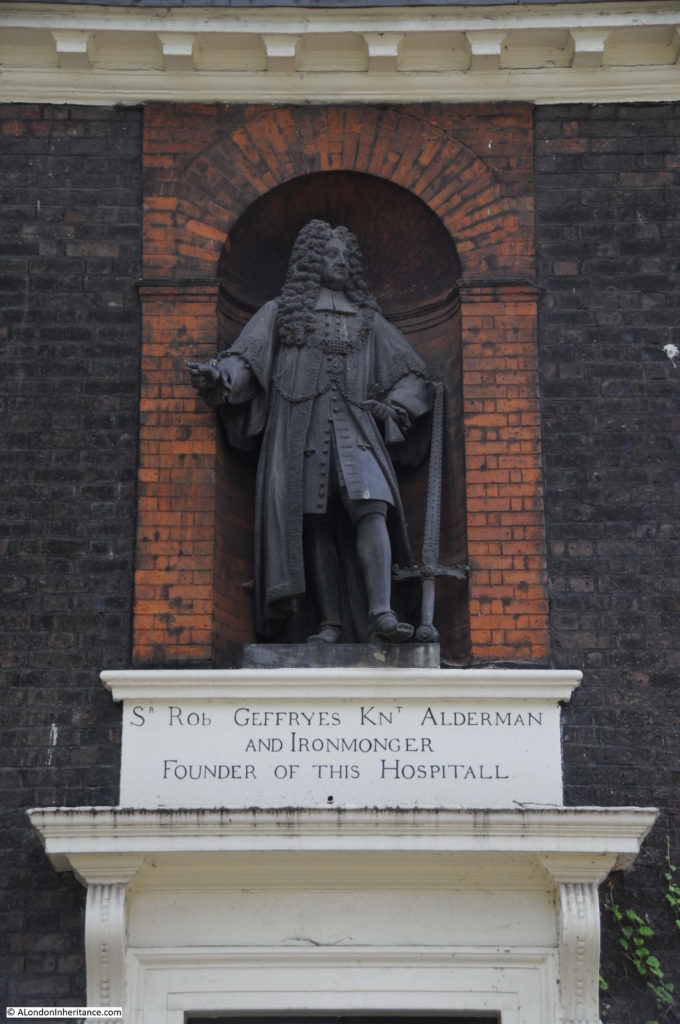

Above the main entrance to the almshouses there is a statue of Sir Robert Geffrye. He was a former Lord Mayor of London and also a previous Master of the Ironmongers’ Company. Geffrye’s bequest after his death provided for the construction of the almshouses.

Again, the Geffrye Almshouses / Museum justifies a dedicated post however I had more sites to visit on the Architects’ Journal map. I left via the entrance at the northern end of Kingsland Road, adjacent to the small cemetery for those associated with the almshouses.

Adjacent to the northern entrance to the almshouses is this old water fountain dated 1865 and the gift of the Hon. Mrs Rashleigh of Berkeley Square. The only Rashleigh’s I can find are a family from Prideaux in Cornwall. Early in the 19th century Philip Rashleigh was the MP for Fowey. In 1873 a Sir Thomas Rashleigh died, again from Cornwall. I can find no reference that they had a house at Berkeley Square, however Robert Geffrye had been born in Cornwall so perhaps there was some association between them.

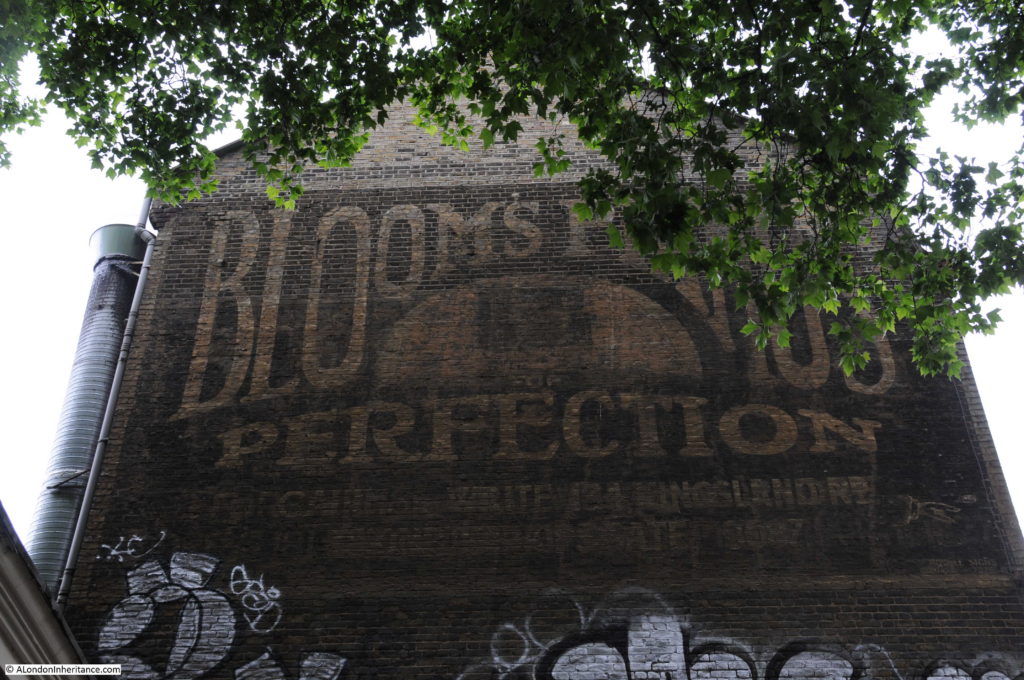

At the southern end of the almhouses, the adjacent building retains a large advertisement for Bloom’s Pianos.

I then walked south along Kingsland Road to the junction with Hackney Road to find:

Site 35 – George Dance’s St. Leonard’s Church and 1735 Clerk’s House

St. Leonard’s Church stands in a prominent position at the junction of Kingsland Road, Hackney Road and Shoreditch High Street. A church has been on the site for many centuries, possibly earlier than the 11th century.

The present church was opened in 1740 after the previous church partly collapsed. Designed by George Dance the Elder the church has an impressive portico topped by an ornate tower.

Walter Thornbury writing in Old and New London however was not impressed with the new church “The present St. Leonard’s Church, Shoreditch, occupies the site of a church at least as old as the thirteenth centruy. The old church, which had four gables and a low square tower, was taken down in 1736, and the present ugly church built by the elder Dance, in 1740, with a steeple to imitate that of St. Mary-le-Bow, Cheapside, and a fine peal of twelve bells. The chancel window, the gift of Thomas Awsten, in 1634, and a tablet to the Awstens, are the only relics left of the old church. St. Leonard’s is the actor’s church of London; for in the days of Elizabeth and James the players of distinction from the Curtain in Holywell Lane, and from “The Theatre,” as well as those from the Blackfriars Theatre and Shakespeare’s Globe, were fond of residing in this parish. Perhaps nowhere in all London have rooms echoed oftener with Shakespeare’s name than those of Shoreditch.”

As with the Geffrye Almshouses I am surprised that the church was included in the Architects’ Journal article as I would have thought there was no threat to the church, even in 1972. The article does though mention several times the risks of “wholesale demolition”, covering large areas without any thought to the buildings that would be demolished – the risks to remaining 18th century buildings in East London seemed very real in 1972.

What may have been at risk was the Clerk’s House which dates from around the same time as the church. This small building is in a corner of the churchyard with a frontage directly onto the street.

A short distance along Shoreditch High Street, at the junction with Calvert Avenue is Syd’s Coffee stall. Both myself and my father have included Syd’s while taking photos around the area over many years. This is from my walk round in 2017:

And in 1986. The car is obviously of the time, but the rest of the photo could be today rather than 30 years ago. The only other obvious change is the phone number for Hillary Caterers from an 01 number in the photo below to an 0181 today.

Syd’s dates from 1919 and there is an excellent article on SpitalfieldsLife covering the history of the coffee stall.

A short distance in Shoreditch High Street from the junction with Calvert Avenue is the last of the locations in today’s post on the category C sites:

Site 36 – All That Remains Of Pre-Victorian Shoreditch High Street

The Architects’ Journal is not that specific regarding these buildings, just stating “all that remains” so it is not possible to check whether all the buildings in 1972 remain in 2017, although I suspect not.

There are a number of pre-Victorian buildings that remain, including this interesting building on the corner with Boundary Passage with a strange set of windows along the side passage included one rather large, blocked up window.

And opposite is this rather nice row of pre-Victorian buildings:

That completes the first part of my walk through the Architects’ Journal category C sites and 45 years after the article was published it is good to confirm that the sites listed as worthy of preservation are still here.

In my next post, I will continue from Shoreditch High Street, via Bethnal Green and Whitechapel to the edge of Shadwell.

Thank you for taking me along with you on this interesting walk, Admin. I’m looking forward to the next post.

P.s. If I don’t always comment on your posts don’t think I don’t enjoy them,it’s just that I’ve run out of ways to say ‘great’

Fascinating post as usual. Only a lottery win stands between me and owning one of those beautiful old buildings.

I recall being taken to visit the Geffrye museum in a school party 65 years ago. Delighted to see that it is still fufilling its educational purpose.

Another fantastic post!

A fascinating article – so many untold stories. We still haven’t made it to the Geffrye Museum.

Hello

The building at 72 Shoreditch High St on the corner of Boundary Passage, is the former Bull & Pump pub. It was the St Leonards Coffee House in 1871 and became a strip club called The Rainbow in 1988.

Vinny

Another great post as usual and another area I know well but I cannot share the enthusiasm for the Geffrye Museum – possibly the worst in London. I concede they are limited by the space but the exhibit consists of an extremely narrow corridor (people walking the other way is a problem) along a series of tableaux of rooms furnished to particular styles. You can’t enter the rooms or examine anything at close quarters.

On a less serious matter I have to take Vinny to task on his dating. He’s quite correct that the Rainbow used to be the Bull and Pump but the conversion was much later … more like 1998. It had already become a strip pub under the Bull and Pump name by the mid-90s when I visited – purely in the interests of local historical research of course. The décor and “talent” were at the bargain basement end of the scale.

Oh, I share the enthusiasm for the Geffrye. I visited a few years ago and found it both charming and extremely interesting. There are tableaux, but also extremely informative write-ups of what you’re seeing and how domestic interior changed over time. I did not notice difficulty in passing. It is true that there are space constraints owing to the very small apartments allocated to each person housed when the site was an alms house.

It’s good to see that most of these buildings are in reasonable condition. You say you are surprised that the Geffrye Museum is included. Indeed I believe it is a grade 1 listed building but it is only a couple of years ago that the Museum submitted plans to hack around its entrance, demolish an ancient pub and construct a concrete entrance. The Spitalfields Life blog campaigned long and hard and eventually the plans were dropped. It seems that it’s not just rapacious developers who need to be guarded against!

Lovely – very much looking forward to the next installment.

One of my London Friday Photos was of the piano sign by the Geffrye:

https://irontongue.blogspot.com/2015/09/london-friday-photo.html

A friend of mine who is also researching the Backler name, made a posting last year about two Backler sisters who were residents at Geffrye’s Almshouses. You might like to take a look at this link.

https://backlers.com/2015/11/

Best wishes,

Ray

Your articles are of great interest to someone living so far , in South Africa , from London . I have managed quite a few visits and love the off the beaten track places you highlight…Keep it up.

BTW a pub The Palms, we stumbled across along Regent’s Canal is apparently threatened with closure.

Grand day out. Glad to see complete lack of uniformity still going strong and long may that continue.

My great great grandfather was hall keeper at Hoxton Hall when it was run by the Blue Ribbon Army .This was after it was a music hall

The family also had french polishing shops in Hoxton Square and lived in Rivington Street

The Site 33 pair of houses are referred to in John Emmerson’s classic book ‘Georgian London’, and photos and measured drawings of their original elaborate interiors can be found in the LCC’s 1922 Survey of London Vol VII.

The right hand house, now numbered No.126 was my Family’s home and business premises for most of the 19th cent. They wove hearthrugs here under the name D.&B.Gladding, and their original iron loom dating from 1832 is in the Reserve collection of the Science Museum.

My Gran,her 8 siblings, mother and father lived at 45 Coronet Street in the 1880’s and early 1890’s.

I’ve no idea how old the present building there is..can you help me? Additionally, are there any older photographs of the place nearer Victorian times?

Also another question. One of my grans brothers, died aged 5 months at that address. I have no idea where he is buried, though I assume St.Leonards . How do I find out? (I gave the relevant death dates etc).

Thank you kindly