Before heading to Shenfield Street, a quick advert. I am still working on a couple of new walks for 2023, which should be ready in a couple of months, however I have set some dates for a limited number of my walks exploring Wapping, the Southbank and the Barbican.

For this week’s post, I am in Hoxton, looking at how Shenfield Street was decorated for the Coronation – the 1953 rather than the 2023 Coronation. This is a series of photos of the street taken by my father. One of the photos includes something that enabled much of his photography across London, and wider afield.

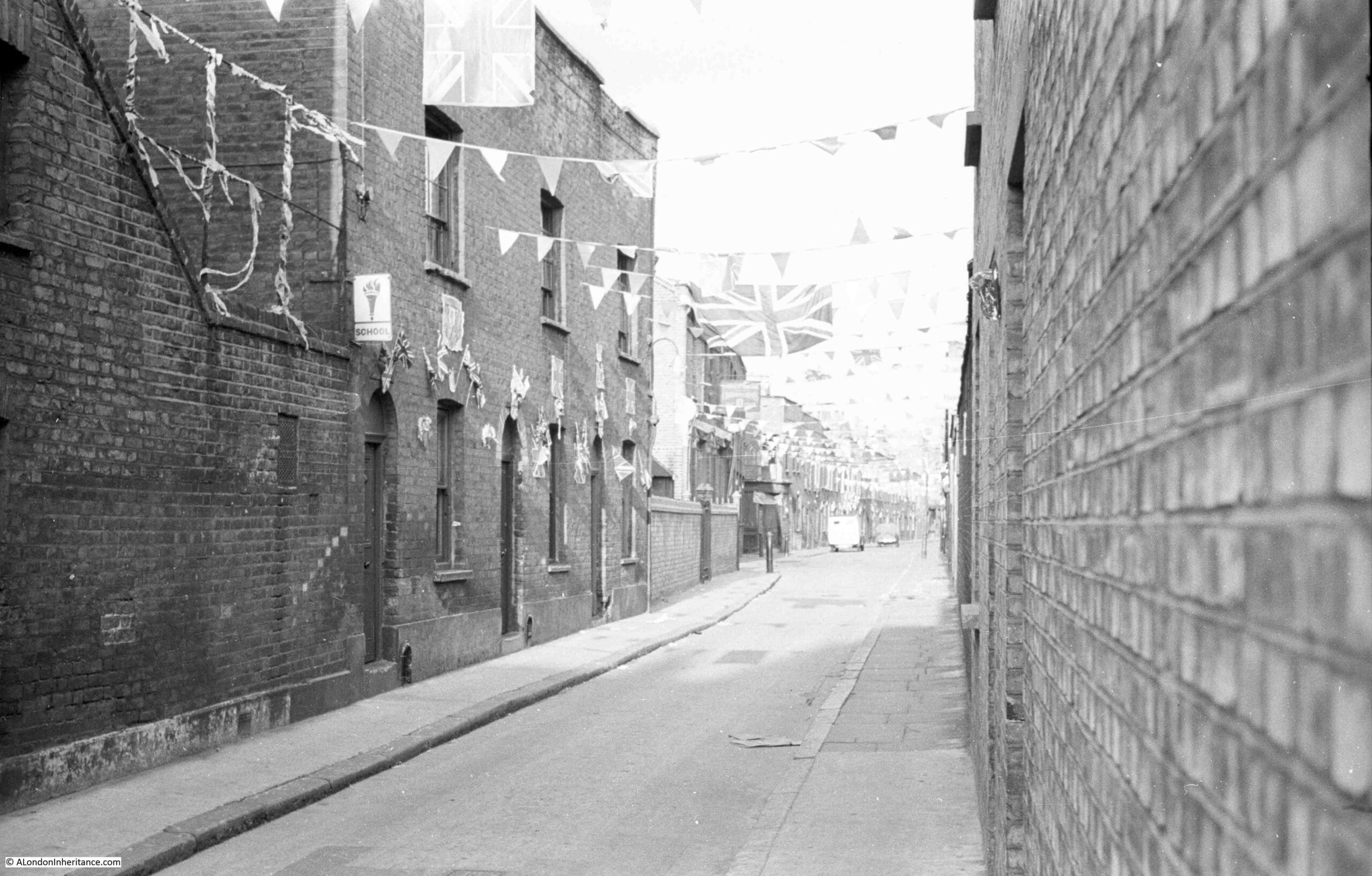

This is Shenfield Street, looking west towards the junction with Hoxton Street, on Sunday the 31st of May, 1953, two days before the Coronation on the 2nd of June:

This is the same view today, at the end of April, just over a week before the 2023 Coronation:

The white building at the end of the street in both of the above photos is the White Horse pub. Open at the time of my father’s 1953 photos, but closed in 2023, having closed as a pub in 2013.

In the 70 years since the last Coronation, Shenfield Street has changed beyond recognition. Once a street lined with terrace houses, they have all since been demolished, to be replaced by the Geffrye Estate.

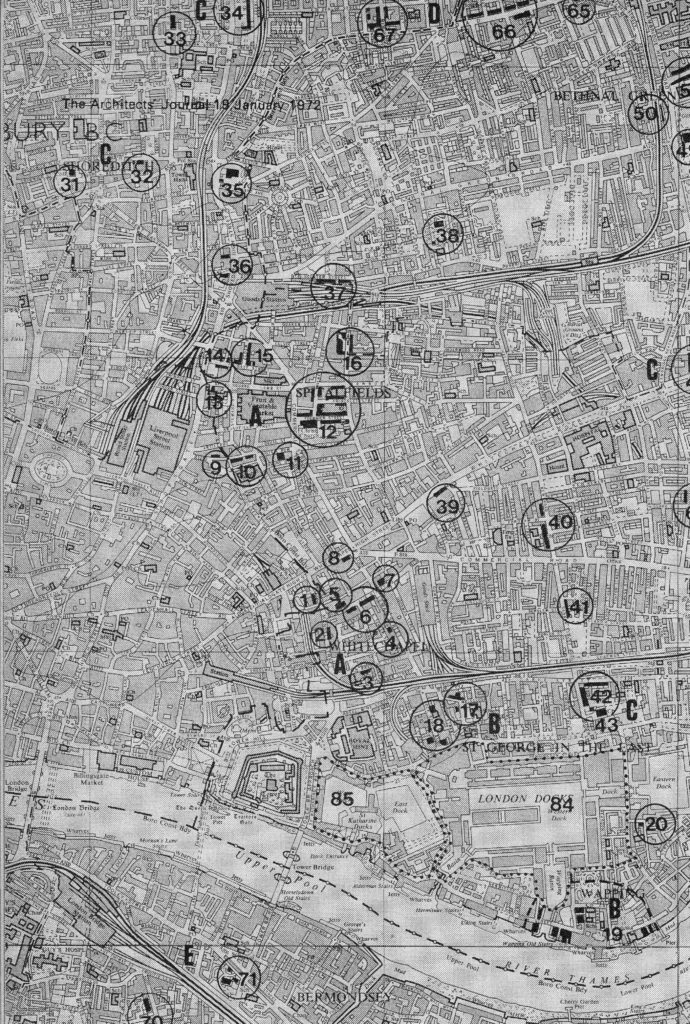

In the following map, Shenfield Street runs across the middle of the map, with Hoxton Street on the left and Kingsland Road on the right. In 1953, Shenfield Street provided a route between the two streets to left and right, but today is blocked for traffic, with only a pedestrian route through as shown by the grey section as the street approaches Hoxton Street (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

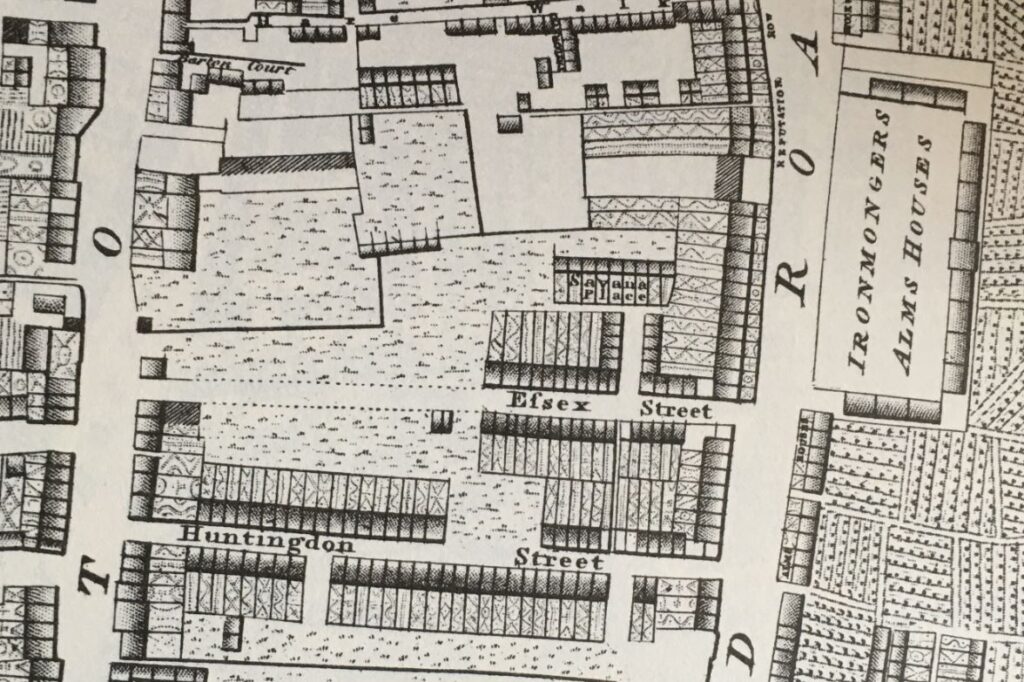

Construction of the street seems to have started in the late 18th century, however in 1799 as shown in the following extract from Horwood’s 1799 map of London, it was then called Essex Street, and is shown running across the centre of the following extract from the map:

The map shows that building started from the Kingsland Road end of the street, and the houses then constructed appear to be densely built terrace houses, which I assume are the same houses that were still to be found in 1953.

The name change is interesting. I cannot find the source of the name Essex Street, or when it was changed to Shenfield Street. Essex Street was still in use in 1915, but had changed by 1945, when Shenfield was recorded in the LCC Bomb Damage Maps.

Street names were often changed to avoid confusion when there was another local street with the same name, however the nearest Essex Street seems to have been leading off from the Strand, a distance from Hoxton.

Shenfield was an interesting choice for the new name of the street, as Shenfield is a town in Essex, probably now better known as the eastern end of the Elizabeth Line. So by choosing Shenfield there was a continuation of the Essex connection.

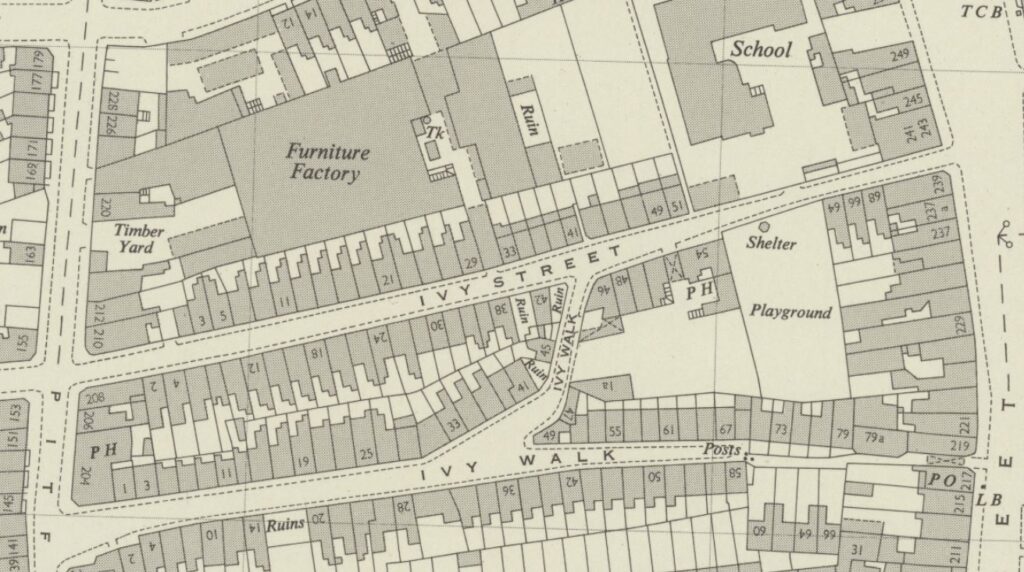

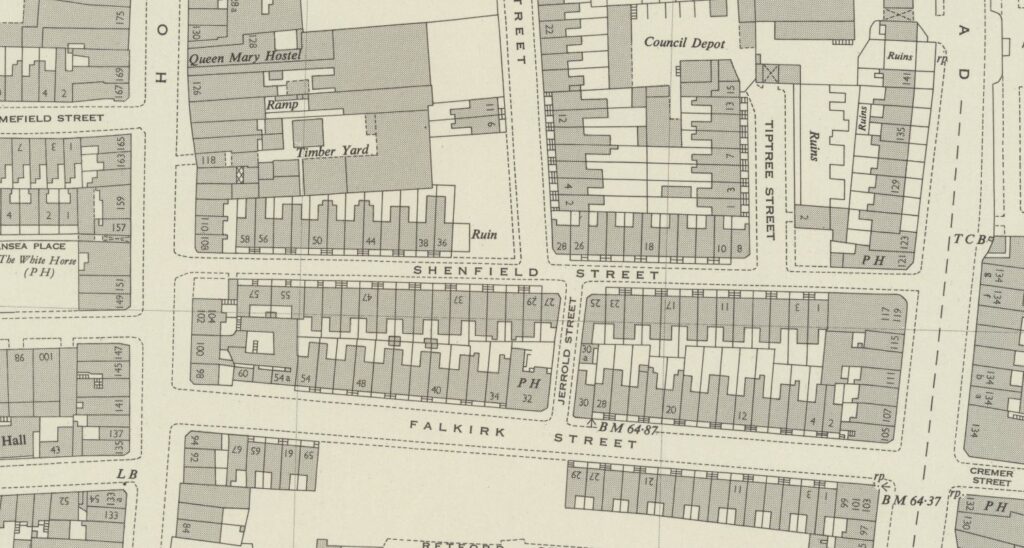

The following map extract is from 1957, and shows Shenfield Street with terrace housing lining the street as in my father’s photos. There is another Essex connection in the map. Towards the right of Shenfield Street, there is a small stub of a street heading north called Tiptree Street. Tiptree is another small town in Essex, some distance towards the northern part of the county, and no connection with Shenfield, so I have no idea why the two streets were given these names (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“).

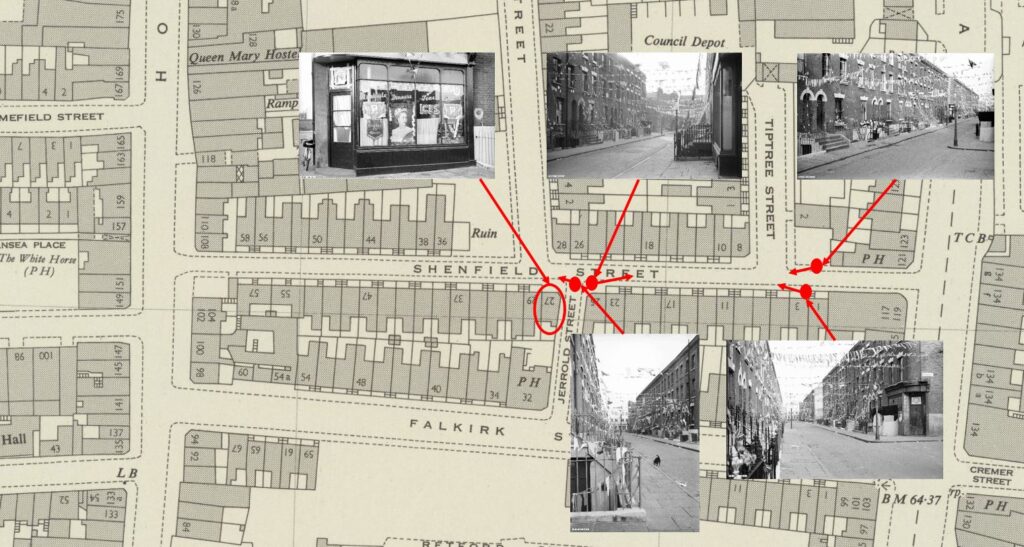

My father took five photos of Shenfield Street, and I have located the position from where he took each photo, and the direction of view in the 1957 map (the first photo at the top of the post is the lower right photo):

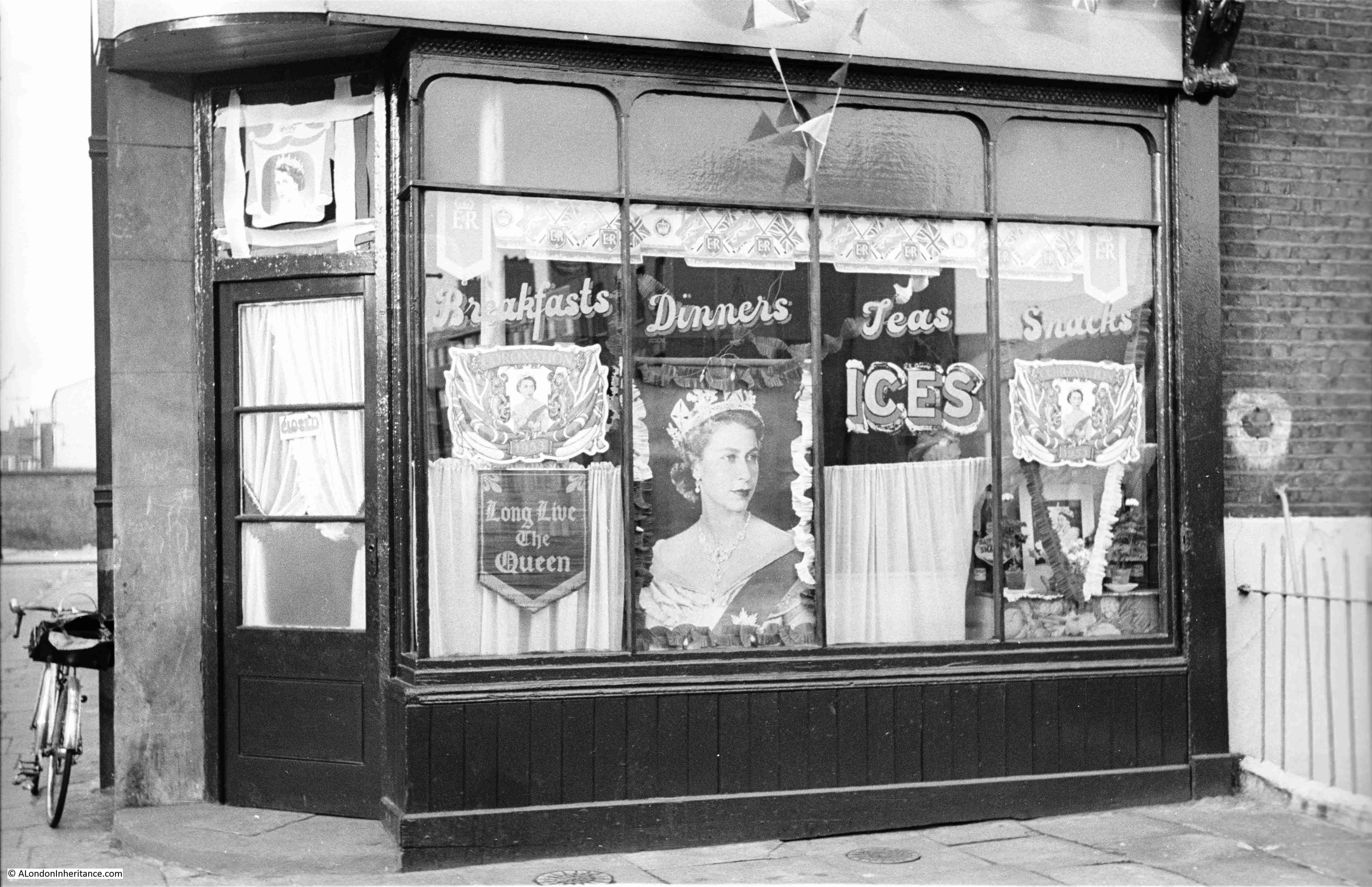

At top left of the above map is a photo that you may recognise as it has been in the header of the home page of the blog since I started in 2014, however I have never been sure of the location. I knew it was around Hoxton, but not exactly where. I will show later how I confirmed the location, that the café decorated for the Coronation was at 27 Shenfield Street, at the junction with Jerrold Street:

The photo is special for me, as it is the only London photo that shows my father’s bike, which is propped up against the wall to the left of the café. The bike took him all over London whilst taking these late 1940s and early 1950s photos, as well as youth hosteling across the country and to Holland.

The café does appear to have been well kept, and the lettering on the windows advertising Breakfasts, Dinners, Teas and Snacks is rather ornate.

Jerrold Street still exists, however at the junction with Shenfield Street, the corner where the café was located has been cut to form an angled entry to Jerrold Street, so in the following photo the café would have been in the roadway and pavement leading back from the drain cover that can be seen in the road:

To the right of the café photo in the above map, is the following view, looking towards where Shenfield Street meets Kingsland Road. The photo was taken from the opposite side of the Jerrold Street junction, and the shop on the immediate right of the photo is at number 25 Shenfield Street:

In the above photo, Tiptree Street is along the street on the left, just after the lamp post, where Tiptree Street runs to the left.

The same view in 2023:

The location of the following photo, and direction of view, is at top right in the above map, it is looking towards the western end of Shenfield Street. The street which is running to the right, immediately in front of the location of the photo is again Tiptree Street:

The same view today, with not so much a street, rather an entrance to the estate leading off to the right, where Tiptree Street was once located:

It was this photo that allowed the location of the café to be identified. I have circled the location of the café in the following copy of the photo:

From the outside, the houses lining Shenfield Street look in a reasonable condition. Although there was significant bomb damage in a number of surrounding streets, Shenfield Street survived relatively unscathed, except for one house that was lost.

In Charles Booths poverty map, at the end of the 19th century, the street was classed as “Poor 18s to 21s a week for a moderate family”. In the following extract from the map, Essex Street as it was at the time of the survey, also has black lines running along the street, which means “Lowest Class, Vicious Semi-Criminal”:

A newspaper report from the 26th September 1922 offers a view of the conditions within the street:

“CROWDED STREET OF DOLE-DRAWERS. Amount Received Exceeds Pre-War Earnings. Every household in Essex Street, Hoxton is in receipt of relief from the Shoreditch Guardians, and the total so received is said to exceed the pre-war earnings of the whole street.

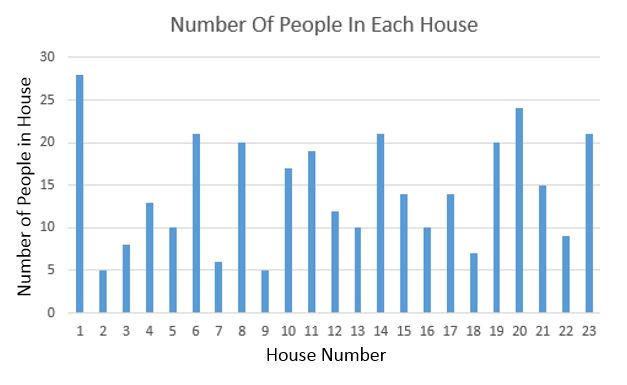

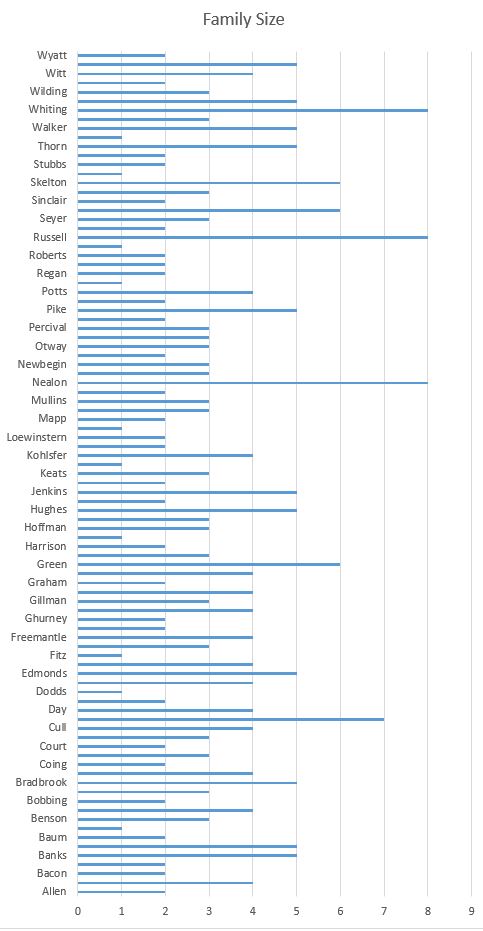

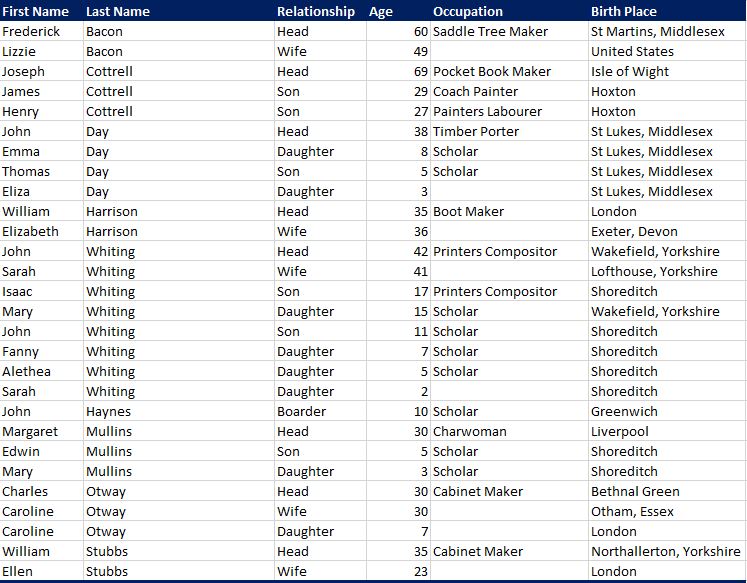

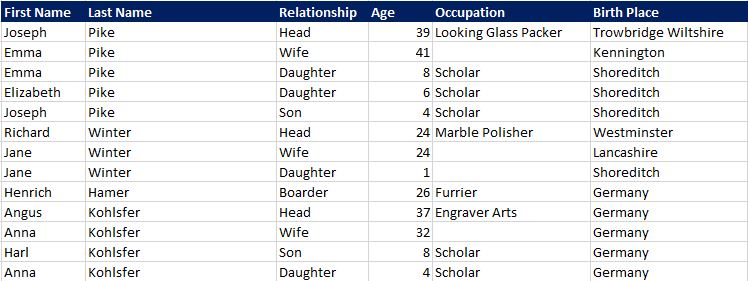

Probably one of the most congested streets in Shoreditch, Essex Street has several houses which are shared by six or seven families, and in one or two instances the number of people in each dwelling reaches 30.

Paper serves for glass in many of the windows.”

So the problem with the houses was not necessarily their construction, rather overcrowding and landlords who probably did not bother which much maintenance.

Another report from August 1939 shows how important it was (and still is), to have green, open space locally available:

“Novelty of Grass – Child Wedged In Railings. Three year old Lillian Turner always likes to visit her grandmother because in the backyard of her L.C.C. flat off Walmer Gardens, Hoxton, there was a patch of grass. She rarely sees grass, for there is none near her own home in Shenfield Street, Hoxton.

While her mother went upstairs to chat with her grandmother yesterday, Lillian ran out to the grass patch. She tried to squeeze through some railings to get to it, but became wedged by the shoulders.

Men passing tried to release her, but were afraid of hurting her and sent for the fire brigade. In a couple of minutes, six firemen with a fire pump and an ambulance arrived, but as they did so, Mrs. Turner managed to release her daughter, unhurt but suffering from shock.”

From the above description, you can understand why post war estate planning, such as the Geffrye Estate which was built following the demolition of the houses along Shenfield Street, included plenty of green space scattered across the estate.

The above two news reports also shrink the period for the name change from Essex to Shenfield Street to between 1922 and 1939.

The following photo is from the lower right position in the above map. Tiptree Street is the street leading off at the right. There is what appears to be an old shop on the corner at number 8, however most of the front of the shop appears bricked up and there is some strange contraption in front of the shop:

Look along the terraces of houses on the right, and half way along there is a light coloured wall. This was an internal wall of a house that was demolished following bomb damage.

The same view in 2023, with what was Tiptree Street on the right, and the location of the old shop was on the patch of grass:

This is the view looking down what was Tiptree Street, today access to the Geffrye Estate without any apparent naming:

Tiptree Street was originally lined with similar terrace houses to those in Shenfield Street. The terrace that was on the left survived the war, however only a single house survived on the right with the rest destroyed by bombing.

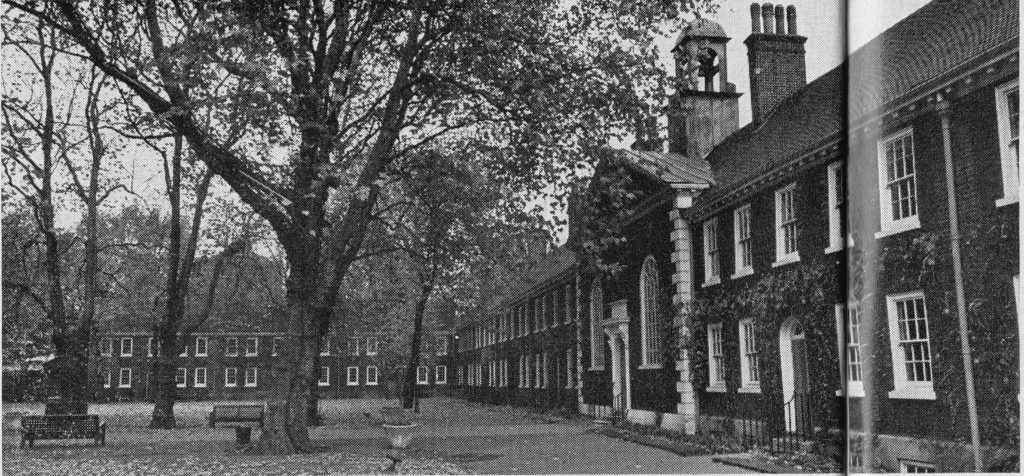

The whole area to the north and south of Shenfield Street is now part of the Geffrye Estate, which I again assume was built during the late 1950s / early 1960s. The estate consists of Geffrye Court, Stanway Court and Monteagle Court, as shown in the following estate map:

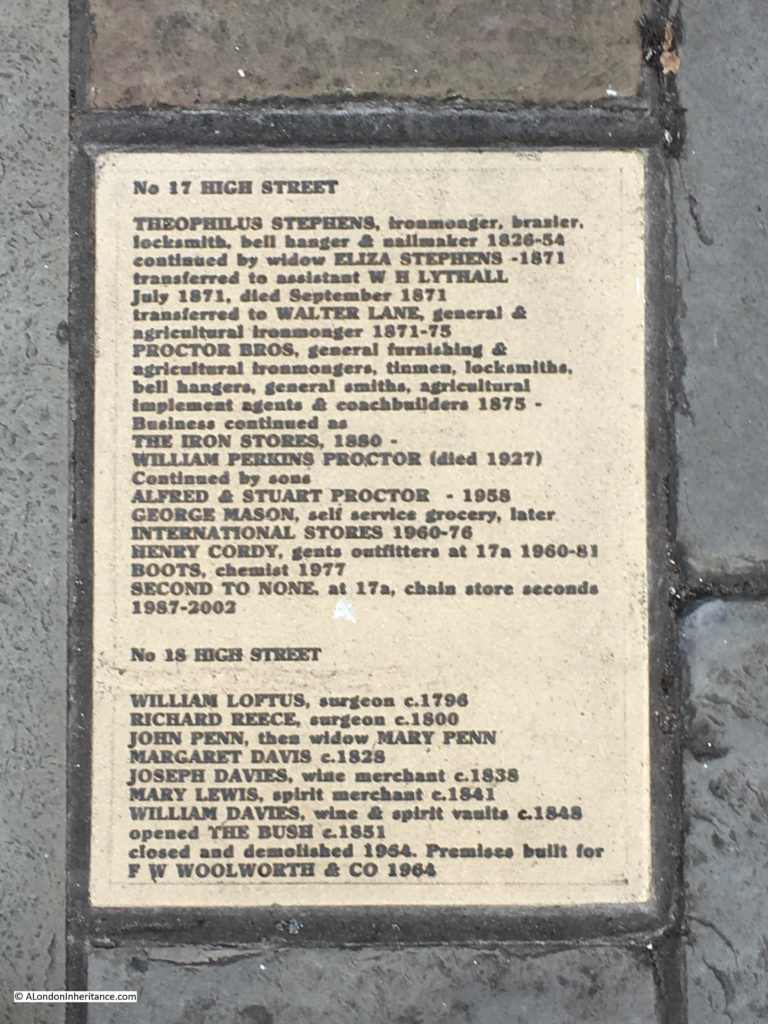

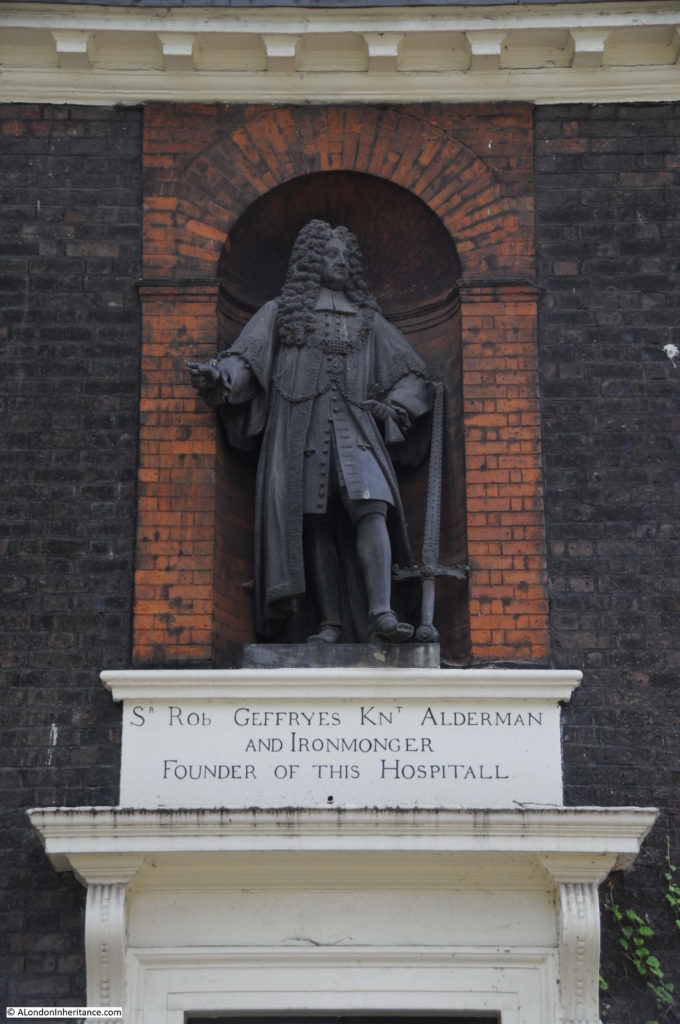

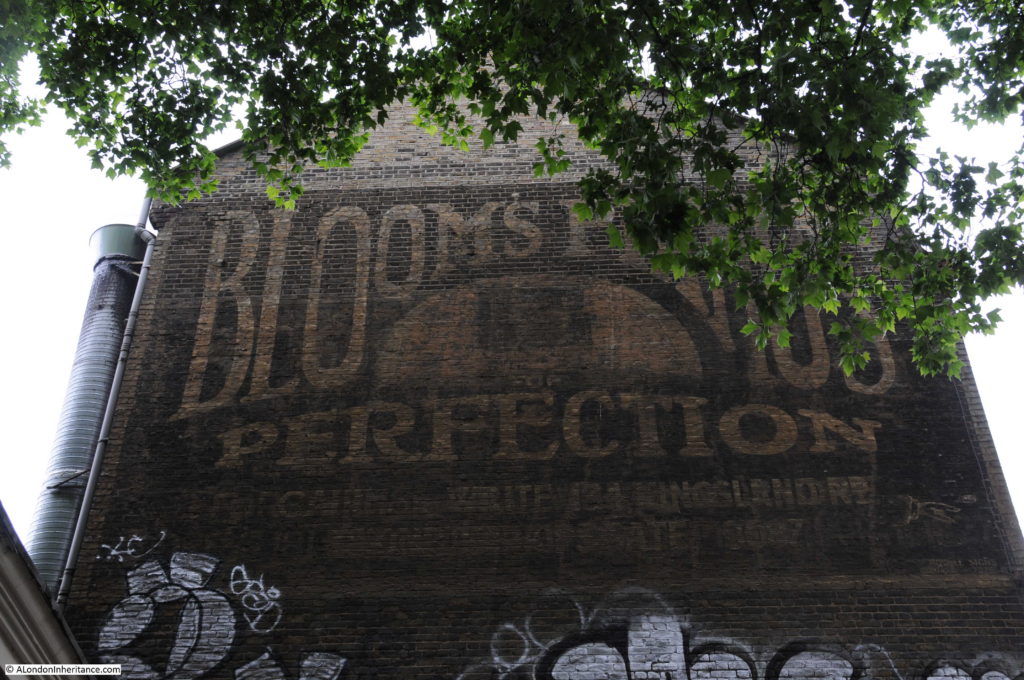

The name of the estate is interesting, and I am surprised it is still in use. I assume it is named after Sir Robert Geffrye who was twice Master of the Ironmongers Company as well as Lord Mayor of the City of London. Geffrye’s financial bequest enabled the Ironmongers Almshouses to be built, which are on Kingsland Road, just north of where Shenfield Street meets Kingsland Road.

The almshouses were purchased by the London County Council in 1911 to save the green space surrounding the buildings, as this space represented a significant part of the green space in the area.

It then became a museum by the name of the Geffrye Museum, however is now called the Museum of the Home.

Sir Robert Geffrye made some of his money from his involvement in the transatlantic slave trade through his investments in the Royal African Company.

Hackney Council have him as a contested figure in their Review, Rename, Reclaim initiative, and the council supported the Museum of the Home in a consultation as to whether a statue of Geffrye at the museum should be removed. The results of the consultation where that it should, however the museum trust decided to retain the statue.

There does not appear to be any mention on the Council’s Review, Rename, Reclaim web pages about renaming the Geffrye Estate.

Going back to the OS map of the street, and where Shenfield Street meets Kingsland Road, and on the northern corner there was the PH reference for a pub. This was the old Carpenters Arms which was demolished at the same time as the rest of the street in preparation for the construction of the Geffrye Estate. The corner where the pub was located is now an area of green space with a block of flats behind as shown in the following photo:

Shenfield Street today is so very different to 1953. I suspect that there must have been a street party along the street, for the street to be so decorated.

The houses in the 1953 photos look substantial and well built houses, although they were probably poorly maintained and in need of much modernisation. The problem with much of this type of housing was very poor maintenance and over crowding. With some care and updating, they could have been retained and would now form a rather impressive street.

Retaining the street would probably not have achieved the number of individual homes that the Geffrye Estate now provides, or the ability to include green space across the estate, a much needed improvement as green space was so very limited in this area of pre-war Hoxton.

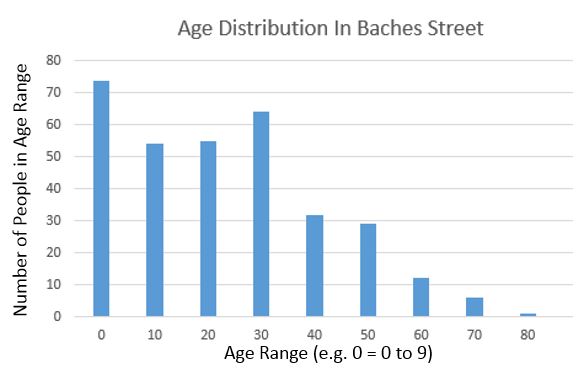

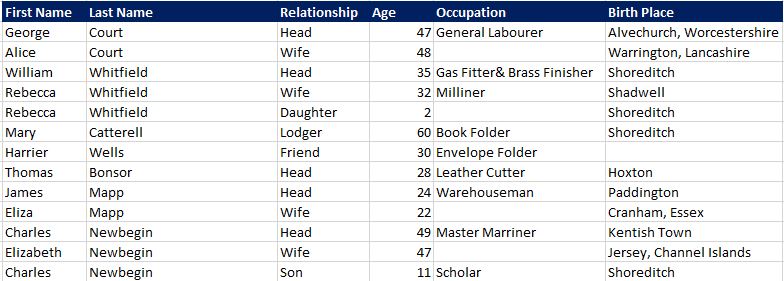

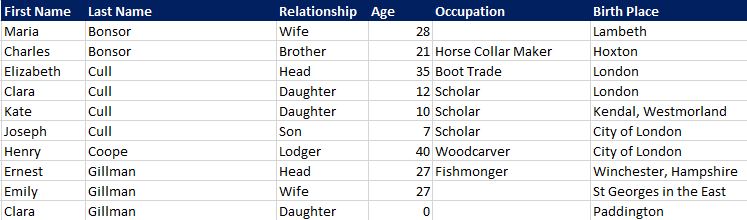

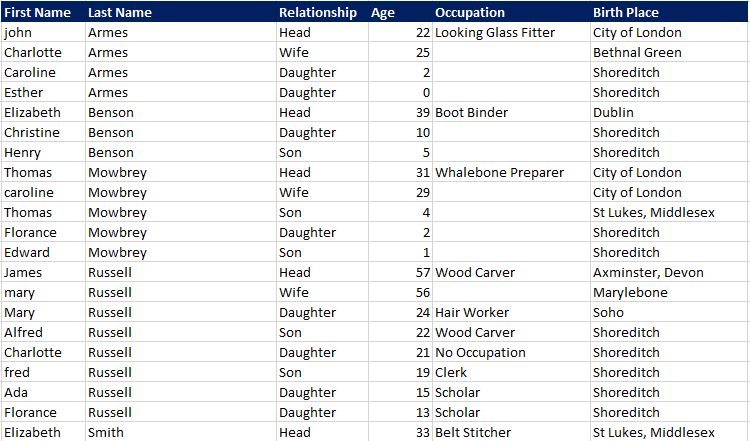

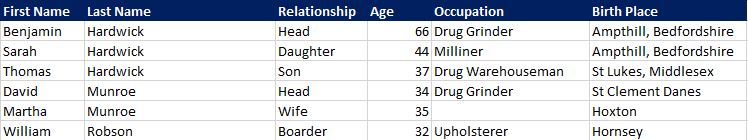

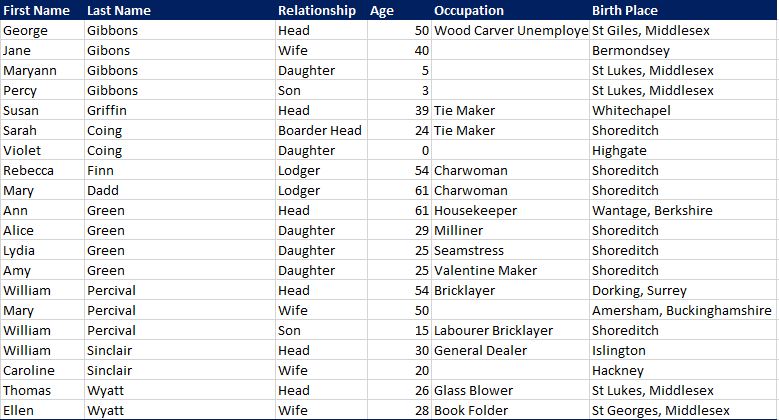

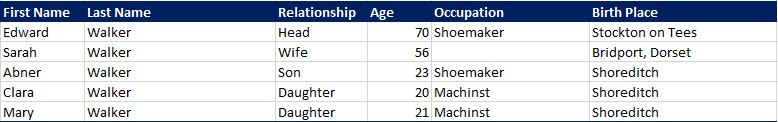

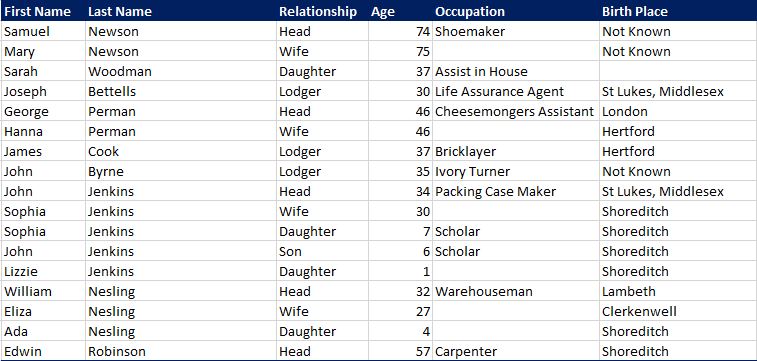

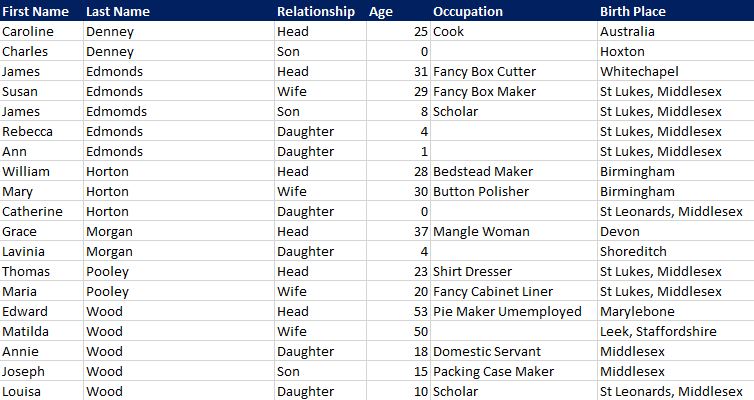

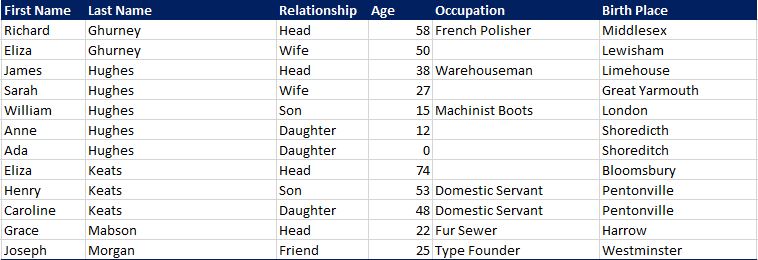

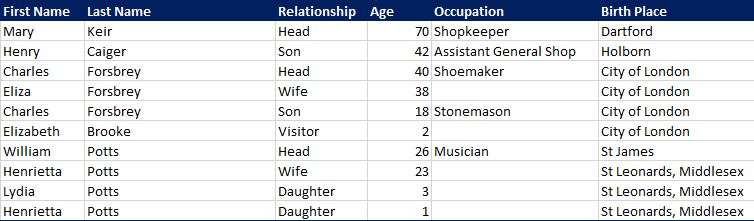

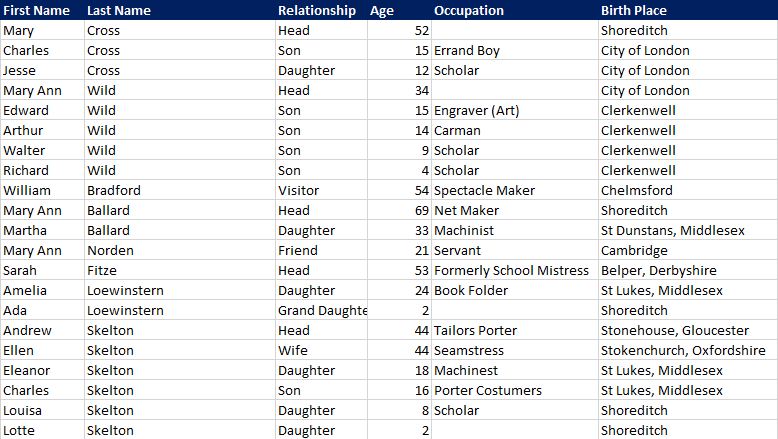

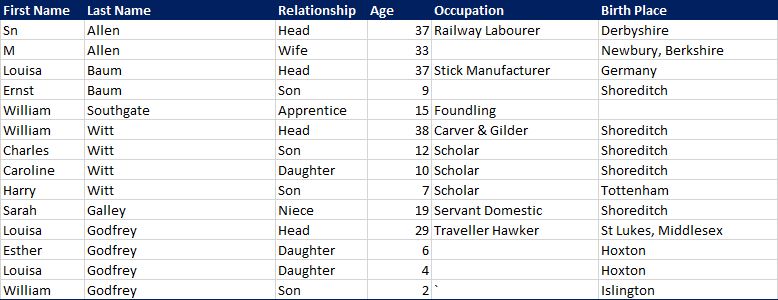

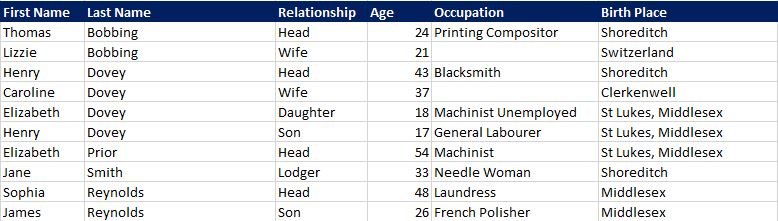

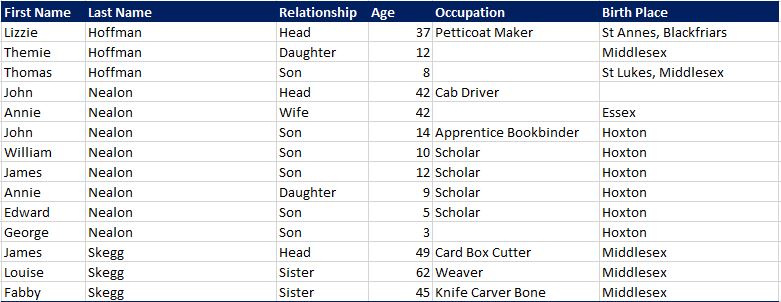

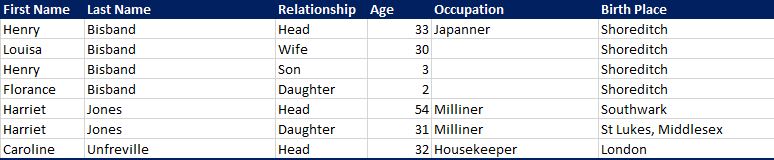

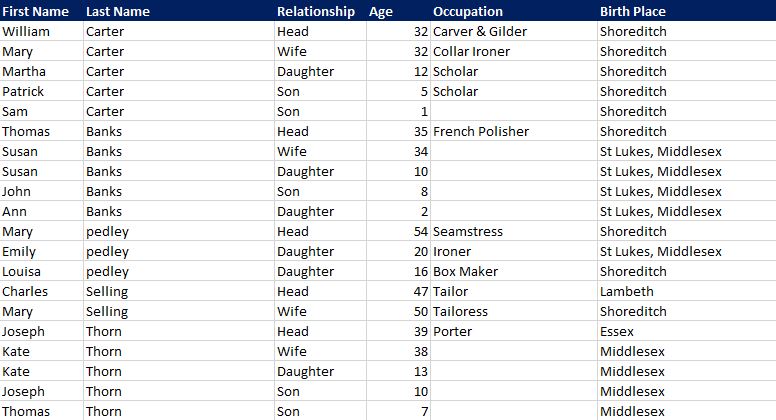

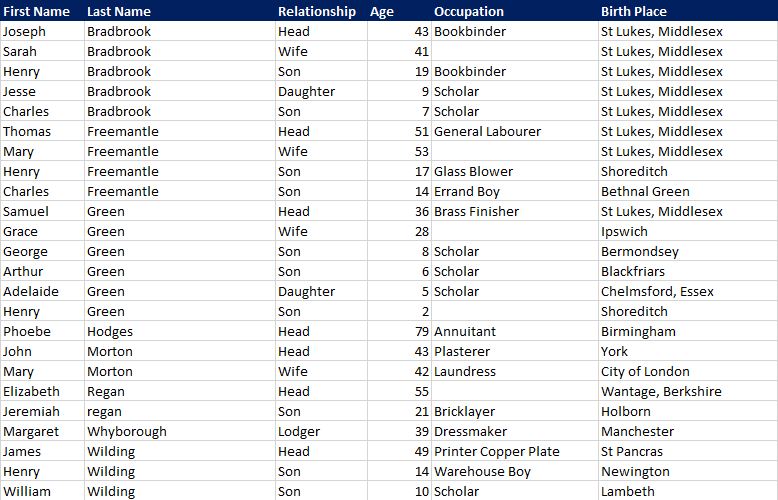

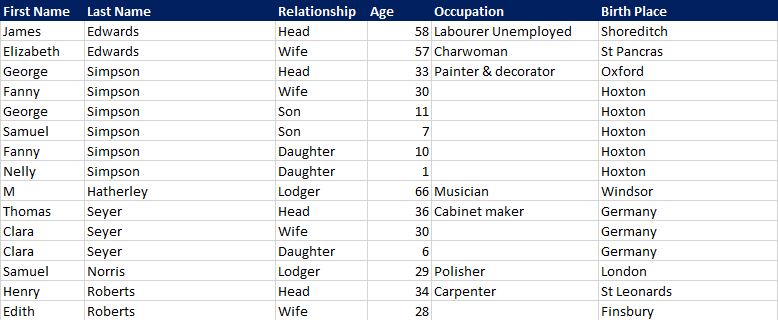

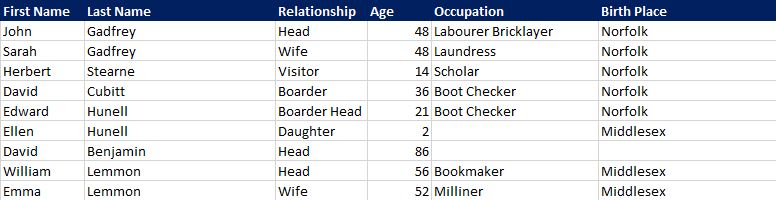

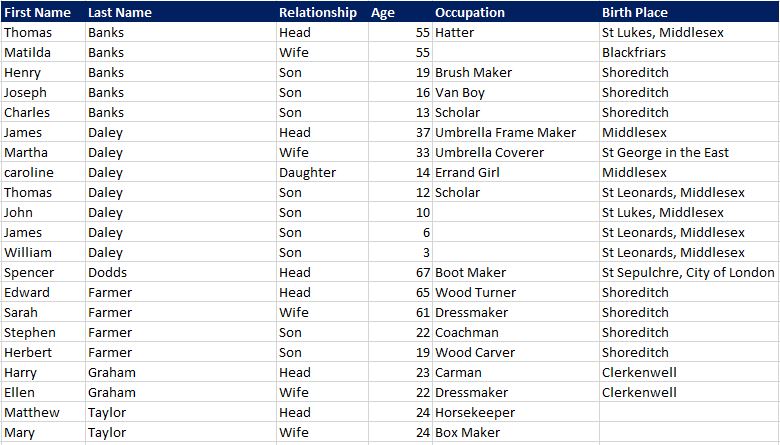

I was planning to use Census data to map who lived in Shenfield Street to each of the houses, as using the OS map, the number of each house is easily identifiable in the photos, although I ran out of time – perhaps I will revisit in a future post.

You may also be interested in a couple of other posts showing Coronation decorations in London in 1953, including Whitecross Street and Ivy Street. Also, this post looked at Coronation Day in London.