Sir Stafford Cripps at Charing Cross Station is one of the more unusual notes that my father wrote on the photos that he printed from his negatives, but that is what I found on the subject of this week’s post and was written to describe the following photo.

The photo was taken at the junction of Villiers Street and Embankment Place at the rear of the Embankment Underground station (the rear assuming that the front of the station is on the Embankment). The same location today:

In my father’s photo, the view is from the outside of what is today the entrance to Embankment Underground Station. At top left are the rail tracks leading from the bridge across the River Thames into Charing Cross Station, with the footbridge running alongside the main rail bridge. The brick buildings line the side of the rail tracks as they run into the main station. Across the street can be seen a couple of awnings in front of some shops in Villiers Street.

I assume the two figures with hats are Police, and it looks like a car has pulled up and the man with white hair is being greeted by the man with dark hair.

My father named the location as Charing Cross Station, but I am outside Embankment Station.

The underground stations around Charing Cross have had a rather complex series of names over the years.

The Embankment Station currently serves the District, Circle, Northern and Bakerloo lines.

Of these lines, the first to be built was the 1870 extension of the District Railway from Westminster to Blackfriars. A station was created on this extension to serve Charing Cross Station, however as the cut and cover construction technique was being used for the railway, it could not run underneath the station, so was run along the new Victoria Embankment. As the aim of the station was to serve Charing Cross Railway Station, it was given the name Charing Cross.

In 1906 the next underground line opened, the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway (the Bakerloo) which also had a station just outside and to the northwest of the main Charing Cross Railway Station which was given the name Trafalgar Square, and the station that terminated at what is now the Embankment Station was an interchange to the District Railway Charing Cross Station, but was given the name Embankment.

The next underground line was the Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway which again had a station just outside the main entrance to the Charing Cross Railway Station, called the Strand Station. The extension of this railway terminated at today’s Embankment, which then was given the full name Charing Cross, Embankment Station.

In 1915 the name reverted back to simply Charing Cross Station, hence my father’s reference to Stafford Cripps at Charing Cross Station.

In 1974, the name changed again to Charing Cross Embankment and a couple of years later, in 1976 the name changed to Embankment and has stayed the same since. The stations outside the main entrance to Charing Cross Railway Station combined and took the name Charing Cross.

I hope I have got that right – any corrections appreciated.

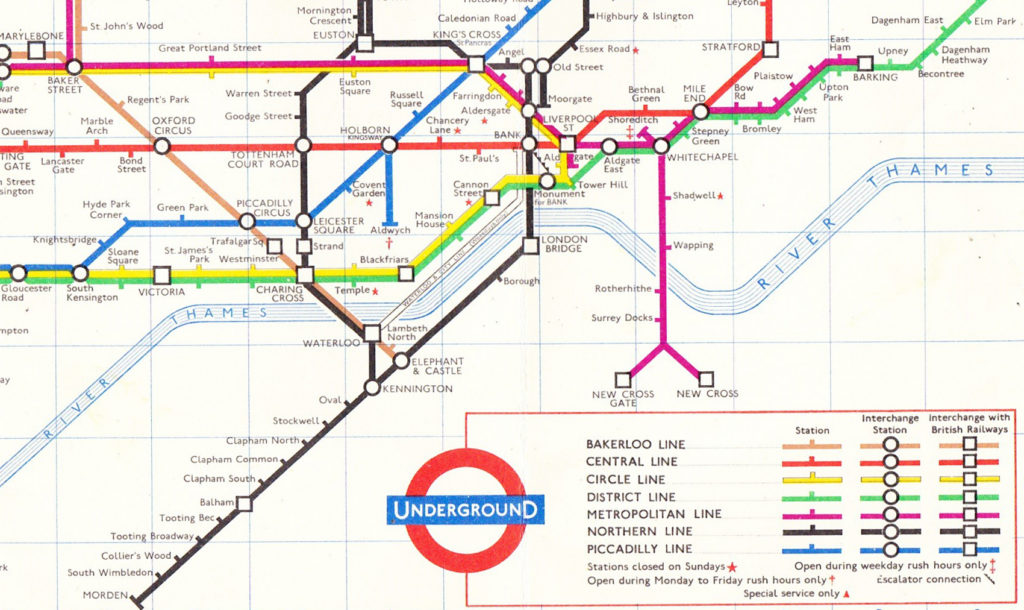

The following extract from a 1963 underground map shows the station configuration with Charing Cross Station where the Embankment Station can now be found with Trafalgar Square and Strand Stations just to the north.

This is the view looking from roughly where the car had stopped in 1948 into the rear of the Embankment Station on a rather wet Saturday:

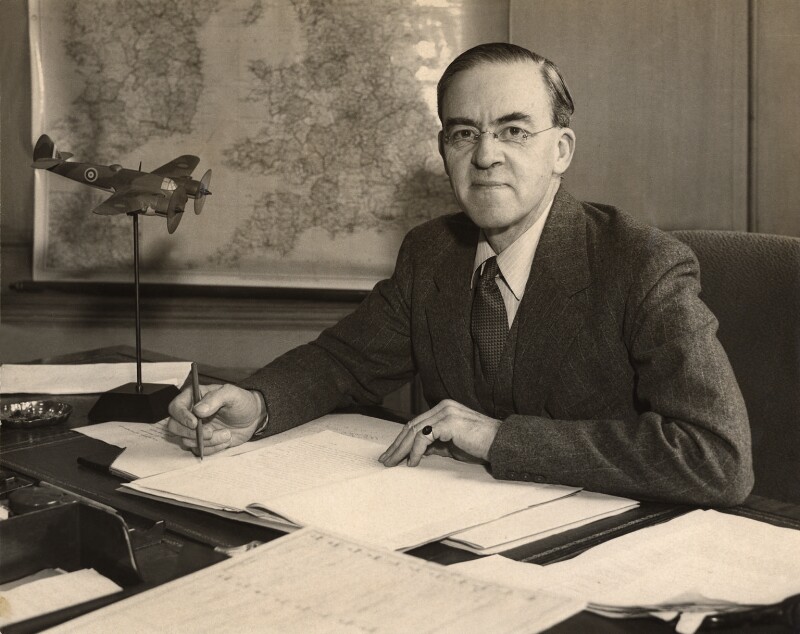

Sir Stafford Cripps was a Labour politician and at the time of the 1948 photos was Chancellor of the Exchequer in the post war Labour Government.

Originally a lawyer, Stafford Cripps joined the Labour Party and was appointed Solicitor General by Ramsay MacDonald. He was highly critical of the National Government that was formed in 1931 and throughout the 1930s argued up and down the country for a form of revolutionary Socialism, to such an extent that a report in the Manchester Guardian stated that “if Sir Stafford Cripps continues, he is much more likely to be the architect of a British Fascism based on the fears of a frightened middle-class than is Sir Oswald Mosley”.

In 1939 he was expelled from the Labour Party after pushing for a Popular Front with the Communist Party, although he would continue to be supported by the constituents of his East Bristol constituency.

Despite being outside of the Labour Party, he was appointed to be the Ambassador to Moscow during the early years of the war, based on Churchill’s believe that a hard left representative would find favour with Stalin. During his time in Moscow, Stafford Cripps reputation grew back at home as he was seen to be strengthening Russia’s resistance to the Nazi invasion.

Back in the UK, from 1942 to 1945 Stafford Cripps was the Minister of Aircraft Production.

Prior to the 1945 General Election Cripps rejoined the Labour Party and after the Labour victory was appointed as the President of the Board of Trade, and from 1947 as the Chancellor of the Exchequer. His time in Moscow had softened his views on Communism as his experiences of Stalin had brought into question the morality of Communism, but he still retained a strong socialist viewpoint.

His training as a lawyer armed Stafford Cripps with a very logical approach to roles such as Chancellor of the Exchequer. He was faced with a country broken by years of war and in urgent need of a rapid growth in manufacturing and export to bring in much needed foreign currency and to rebuild the country after six years of war.

I searched newspapers for any reference to Stafford Cripps visit to Charing Cross Station, but could not find anything – it did not help that my father did not record the actual date in 1948. There are though hundreds of newspaper reports of Stafford Cripps speaking in his role as Chancellor of the Exchequer, calling for more steel production, the expansion of manufacturing, more export, and arguing the case for austerity due to the countries financial condition.

Despite the need for austerity, Stafford Cripps did support high levels of expenditure on social causes such as housing and health.

Stafford Cripps had suffered from Colitis for many years, and his deteriorating health forced him to resign in 1950, and he would die two years later on the 21st April 1952.

The London Daily Herald wrote on the following day:

“By the death of Sir Stafford Cripps the country loses one of its greatest servants, the Labour Movement one of its greatest members.

His intellectual gifts won him pre-eminence, whether at the Bar or in politics. But he added to them other and perhaps greater qualities. He was a man of complete integrity, of superb courage, and of selfless devotion to duty.

He did not flinch, when the war was over, from the task of warning the country, first as President of the Board of Trade, then as Chancellor, of the bleakness of the economic outlook and of the continuing need for austerity.

That earned him for a while unpopularity and even derision in many quarters. But derision turned to respect and admiration as it was realised how sound his judgement and advice had been.”

In addition to the first photo at the top of the post, my father took a second photo which looks to have been taken from just inside the station with the walls of the station entrance to the right and above.

Two men are walking towards the station entrance, with a policeman by their side. One is wearing a chain of office and the other is wearing a bowler hat. What I do not know is which one is Stafford Cripps.

I am not aware that the position of Chancellor of the Exchequer comes with a chain of office, however I get the impression that the man in the above photo in the middle appears to be the most important.

The following photo is of Sir Stafford Cripps in 1942. Is he the man with the Chain of Office or the man with the bowler hat? (photo NPG x88329 © National Portrait Gallery, London)

In some ways I am left with more questions than I have answered in this post. Whilst I have found the location of the original photos, I cannot be certain which of the men is Sir Stafford Cripps and I have no idea why he was walking to the Embankment Underground Station on a wet day in 1948.

I also do not know whether my father was at the station to take the photos, or whether he was just passing and happened to see a famous politician, he nearly always had his camera with him so perhaps this was how the photographs were taken.

Really like this mysterious post!

Maybe another question is: what was close by in 1948 that he would be visiting?

Within walking distance of the car…

Maybe looking at a site for the National Theatre?

This seems to be something he was involved with in 1948.

I look forward to seeing if someone can find you the answers!

Sorry,

he was obviously catching a train from Charing Cross to – where?

I suspect the chap with the chain is the Mayor of Westminster: I believe in 1948 that was Hal Gutteridge. I believe he came from Australia but I can’t immediately find a good photo.

I doubt the chaps with peaked caps are policemen. They are walking towards the Underground station: might they be London Transport officials?

Hal Gutteridge is on this video c1947.

https://www.britishpathe.com/video/christmas-tree-in-trafalgar-square

are you aware of this Museum? https://www.cameramuseum.uk/museum-gallery

I so enjoy your blogs, most interesting and thanks

On January 1 1948, Sir Stafford Cripps opened the ‘How Goes Britain?’ exhibition at Charing Cross Station, according to the January 2 1948 edition of The Times (https://www.thetimes.co.uk/archive/article/1948-01-02/4/11.html#start%3D1785-01-01%26end%3D1985-01-01%26terms%3D“Stafford%20Cripps”%20″charing%20Cross”%20%26back%3D/tto/archive/find/%252522Stafford+Cripps%252522+%252522charing+Cross%252522+/w:1785-01-01~1985-01-01/1%26next%3D/tto/archive/frame/goto/%252522Stafford+Cripps%252522+%252522charing+Cross%252522+/w:1785-01-01~1985-01-01/2).

Thanks, I was unable to find any reference to why he should have been there, but this must have been the reason. Thanks for letting me know.

Just got around to looking at these comments again.

I Can’t see the Times article but will research the exhibition – just out of personal interest.

Well done! to you anyway – impressed you answered the question as to what he was doing.

No problem.

I thought the paper’s description of the exhibition was quite interesting:

‘The exhibition shows graphically the econo- mic condition of the country. Those who require further information can obtain it by picking up a telephone, through which they can hear the voice of Sir Stafford Cripps explaining how the country ca overcome its difficulties. Various quizzes on exports, coal, savings, and manpower are provided and ingenous electrical devices tell the visitor whether he has the right answer.’

There’s also a photo in the RIBA archive: https://www.architecture.com/image-library/ribapix/image-information/poster/how-goes-britain-exhibition-charing-cross-underground-station-london/posterid/RIBA63500.html.

And here I thought interactive exhibits were a late 20th century invention.

There are bits of information about this exhibition online (I wonder where there was space for it in the underground station, but anyway…) Seems to have been put together by the Central Office of Information, intended to last for six months, designed by Misha Black with displays of information that could be changed each month.

There seems to have been a series of these exhibitions at Charing Cross Underground station: Harold Wilson, as President of the Board of Trade, opened one entitled “Britain in the Balance” in April 1948, on increasing industrial output, and Aneurin Bevin opened one in 1949 on “Housing in London”. It seems there were regular exhibitions there for from the early 1930s until at least the late 1950s. I wonder if any of your readers can remember these exhibitions.

I’ll accept the “any corrections appreciated” invitation then… 🙂

The Baker Street and Waterloo didn’t have a station “just outside” Charing Cross railway station as you suggest, the entrance was about 500ft away and it ran beyond Embankment rather than terminating there. The Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead did have a station just outside, but it wasn’t called Strand when it opened. Let’s start from the beginning:

1870, the District opened their Charing Cross station as you describe.

1906 the Baker Street and Waterloo (Bakerloo) opened their Trafalgar Square station (with entrances at the Square) and their Embankment station which was directly under and connected to the District’s Charing Cross. Their lines continued on to and through Waterloo.

1907 the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead built their Charing Cross station – their terminus – adjacent to the main entrance to the main line railway station.

1914 the CCE&HR extended their lines to a new terminus connecting with the District and Bakerloo. Their Charing Cross became Charing Cross (Strand) and their new station along with the Bakerloo’s adjacent Embankment and the District’s Charing Cross all became Charing Cross (Embankment). The cumbersome names were it seems not intended to be permanent, but to assist the public with the transition.

1915 Charing Cross (Embankment) became Charing Cross (the third name for the Bakerloo station, reverting to the original name for the District and the second name for the CCE&HR. At the same time Charing Cross (Strand) on the CCE&HR became Strand. (And also at the same time, the Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton’s Strand station which had opened further along Strand in 1907 was renamed Aldwych (now closed) so as not to have two separate Strand stations.)

Everything then stayed the same for 59 years with the casual usage of District, Bakerloo and Piccadilly becoming formal names and the CCE&HR becoming part of the Northern.

BUT

As part of a grand plan for a tube line under Strand and Fleet Street, the Jubilee Line was to be built taking over the Stanmore branch of the Bakerloo and running through new tunnels from Baker Street to an alignment under Strand ready for a future extension. One end of the new temporary terminus would be well-placed to interchange with Charing Cross mainline station and Strand on the Northern, but the other end of the platforms was equally well placed for an interchange with the Bakerloo’s Trafalgar Square. What name to give the new interchange?

SO

1973 Strand (Northern) closed for major engineering work.

1974 Charing Cross (Northern, Bakerloo, District) renamed Charing Cross Embankment – its 1914 name but sans-brackets this time round I think.

1976 completing that transition Charing Cross Embankment renamed Embankment – the Bakerloo’s original name for its station there. Some sources put that later, but others have the appropriate map extract to prove it.

1979 Strand (Northern) reopened, but renamed Charing Cross (as it was in 1907 when it first opened) along with the new Jubilee Line Charing Cross station, and at the same time Trafalgar Square was renamed Charing Cross and linked to the Jubilee, and via a very long subway direct to the Northern.

1999 Charing Cross (Jubilee) closed as the original plans to extend the line east from there had been abandoned and it took the route we see today instead. The long subway linking the Bakerloo and Northern remained open.

By the way – the Piccadilly’s Strand which had been renamed Aldwych was closed in 1994. At some point the old station canopy with Aldwych on it was taken down and we can now see tiles reading Strand.

Thanks Chris – always pleased to receive corrections, always learning about London. Will have a detailed read through.

Hi there, we run Charing Cross Market, the entrance to which is shown on the modern day image of Villiers Street and the heir to the stalls which were then above ground in the earlier photo. Would it be alright if we used the first two images in a blog post about the history of the market please? We’d credit them to you and link back to your blog of course.