The procession carrying Eleanor’s body now commenced the final part of the journey, which would take Eleanor’s coffin through the City of London, then west towards Westminster Abbey where she would be buried.

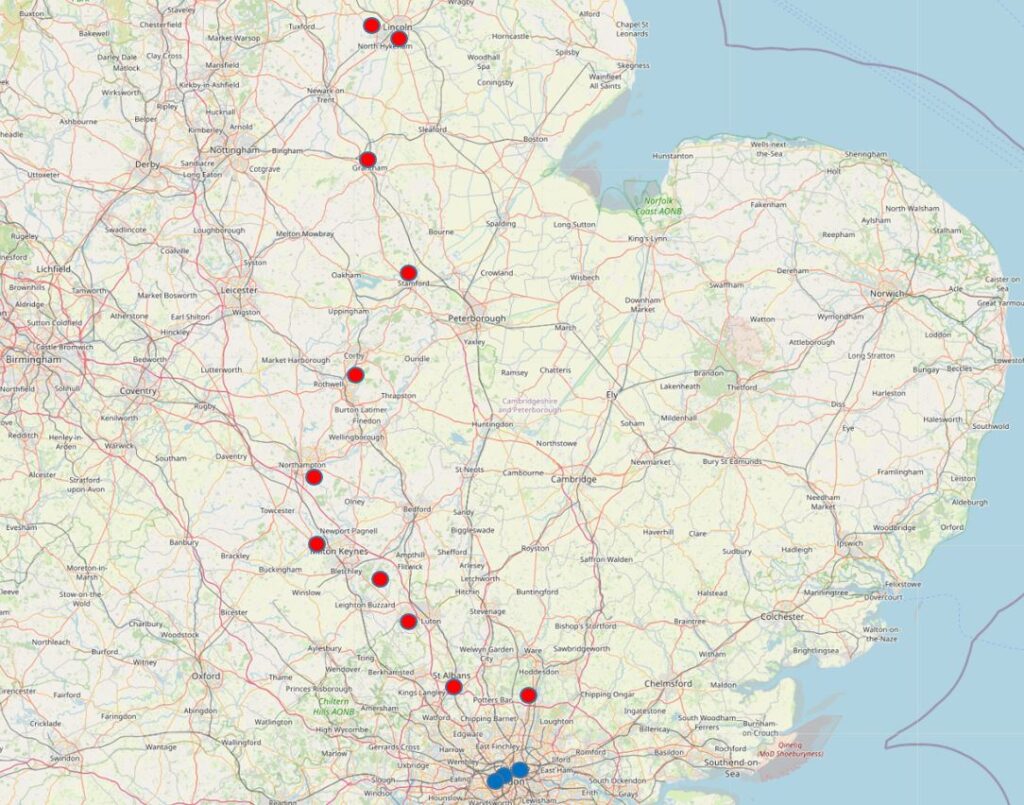

In the following map, three of the key places in London are highlighted with blue circles – Cheapside, Charing Cross and Westminster Abbey, however there were a number of other places which were involved with Eleanor’s funeral, which I will also cover (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

The map also shows the distance covered by the procession taking Eleanor’s body from the site of her death in the small village of Harby at the very top all the way to London. Each of the red circles indicates one of the overnight stopping points which I have covered in previous posts.

The procession left Waltham Abbey on Thursday the 14th of December 1290, headed to the location of the future Waltham Cross, where it turned south towards London.

The aim of the easterly diversion to Waltham Abbey may have been due to the importance of the Abbey, and it may also have been to allow an entry into the City from the east, as the procession entered the City of London through the gate at Bishopsgate.

Once in the City of London, the procession stayed in the east of the City, and headed to Holy Trinity Priory in the Minories, which I wrote about in an earlier post here and here.

Eleanor’s coffin rested in Holy Trinity Priory overnight, and the procession set off again the following day to head west. Passing along Cheapside, one of the main streets of the City, the procession headed to the Franciscan friary of Grey Friars, which I have touched on in this post.

After Grey Friars, Eleanor’s coffin was taken to the old St Paul’s Cathedral, where it probably stayed overnight as it would not head to Westminster until the following day.

An Eleanor Cross was built in Cheapside, possibly confirming that Eleanor stayed overnight in St Paul’s, also because the procession had passed along Cheapside, and also because Cheapside was a major City street, and it has been clear from finding the sites of the previous crosses that they were placed in prominent positions. Edward I wanted Eleanor remembered, so putting a cross in a prominent place would ensure that Eleanor was kept in the public memory for centuries to come.

There are no remains of the Cheapside cross today, however we do have a record of its location.

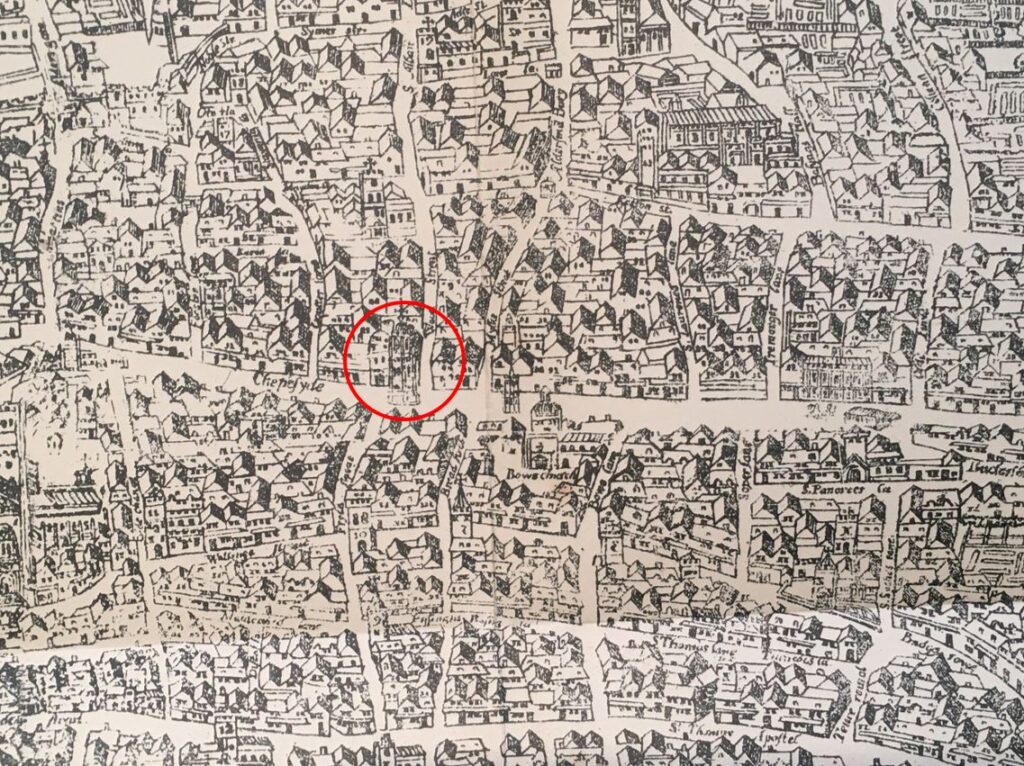

The so called Agas map of around 1561 (probably wrongly attributed to the surveyor Ralph Agas), shows the cross in Cheapside, circled in the following extract:

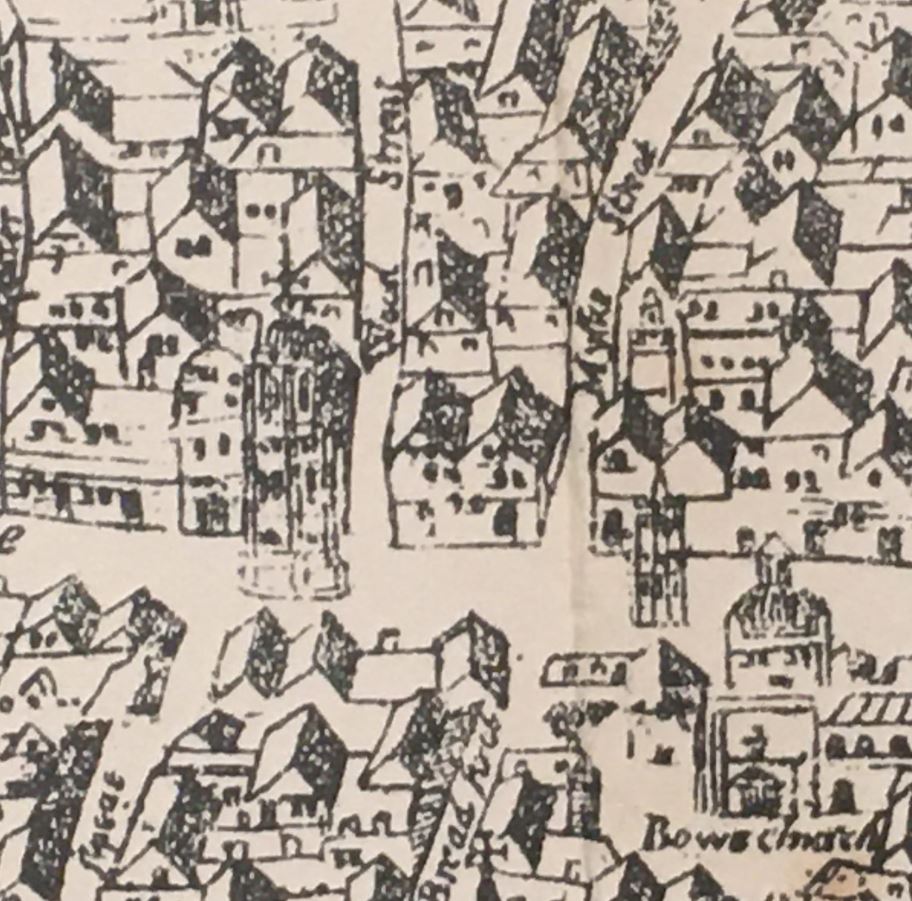

The cross was located just to the west of where Wood Street joins Cheapside, as can be seen in the followed detailed extract from the Agas map:

The Eleanor Cross is to the left, and Wood Street can be seen heading north from Cheapside. There appears to be another, much smaller cross just to the east, and Bow Church can be seen in the lower right of the map.

In the following photo, I am standing in the middle of Cheapside, looking west. The tree on the right is in Wood Street, so the Eleanor Cross would have stood in the middle of the road, just behind and to the right of where the person is crossing the road.

Just in Wood Street, and to the right of where the tree is located, was the church of St Peter, West Chepe, and in the book “London Churches Before The Great Fire” by Wilberforce Jenkins (1917), the old church was described:

“The ‘Church of St Peter, West Chepe, stood on the corner of Wood Street, Cheapside, and was not rebuilt after the Fire. The well-known tree in Cheapside marks the spot, and a small piece of the churchyard remains. It was sometimes called St Peter-at-Cross, being opposite the famous Cross which stood in the middle of the street, and was at one time an object of pride and veneration, and at a later period the object of execration and many riots, until pulled down and burnt by the mob. The date of the ancient church is uncertain, but there would appear to be a reference to it in 1231. In the ‘Liber Albus’, one Geoffrey Russel is mentioned as having been present when a certain Ralph Wryvefuntaines was stabbed in the churchyard of St Paul’s and being afraid of being accused, fled for sanctuary to the Church of St Peter.

Thomas Wood, goldsmith and sheriff, is credited with having, in 1491, restored or rebuilt the roof of the middle aisle, the structure being supported by figures of woodmen. Hence, so tradition says, came the name of the street, Wood Street.”

The “famous Cross” mentioned in the above extract in bold text, was the Cheapside Eleanor Cross.

The cross was a large structure and had been rebuilt in the late 15th century when it was decorated with religious iconography including images of the Pope and the Virgin. From the mid 16th century onwards, the cross was the subject of attack by puritans who objected to the religious symbols on the cross.

On the 2nd of May, 1643, the cross was demolished, an act which was illustrated in the following print produced by Wenceslaus Hollar in the same year (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

1643 was one of the early years of the English Civil War, and was a time when many of the Eleanor Crosses were destroyed. They were seen as being religiously symbolic and it was also the royal references which led to damage and destruction of the crosses.

The Cheapside Cross had been rebuilt and by the end of the 15th century appears to have been more a religious monument than the original design dedicated to Eleanor, The text that goes with the above print states that “Leaden Popes burnt in the place where it stood”, which must have been lead statues of the Pope which had been placed on the cross.

The lower part of the print shows the “Boocke of Sportes” being burnt where the cross stood on the 10th of May.

The Book of Sports was a controversial book originally published by James I in 1618. This was in response to the growing Puritan influence on the church, which tried to ban sports and pastimes on Sundays. Not a popular action given that Sunday was the only day off for much of the population. The Book of Sports was a declaration confirming the right of all persons to engage in ‘lawful recreation’ on Sundays after they had attended a church service.

The book was reissued by Charles I in 1633, and he ordered the document to be read in churches to make clear that people could continue with their normal recreations after service.

The growing Puritan influence brought about by the Civil War enabled the restrictions on Sunday recreations to be imposed, and the Book of Sports was often burnt as shown in the print.

On the assumption that Eleanor’s coffin stayed in St Paul’s Cathedral overnight, if not, it must have been a nearby religious establishment, the procession left on Saturday the 16th of December 1290, and headed to the Dominican Priory at Blackfriars, where a mass was held.

If you remember back to the first post in this series, Eleanor’s heart had been one of her organs removed in Lincoln, and the box containing the heart had travelled separately to London, where it was held at Blackfriars. We shall return here at the very end of the post.

Leaving Blackfriars, the procession then continued west to Westminster Abbey, passing through the village of Charing, the name of which appears to have come from the old English word for a bend in a river.

Charing was the site for the last of the Eleanor Crosses, built by the King’s Mason Richard Crundale between 1291 and 1293. Richard was helped by his son, and here is another example of how difficult it is to be sure of names and facts. The English Heritage references to the cross refer to his son Robert, however The London Encyclopedia by Ben Weinreb and Christopher Hibbert, refers to his son as Roger. A minor detail, but I do find that unless you can find an original, primary resource, it is very difficult to be absolutely sure of facts.

The Charing Cross was apparently the most impressive of all the crosses, which would have made sense given the location of the cross.

It was taken down on the orders of Parliament in 1647, and the stones were allegedly used in various building works in Whitehall.

The site of the cross was where the statue of King Charles I stands today, on the edge of Trafalgar Square, seen slightly to the right of the following photo:

The Agas map also shows the Charing Cross, and as can be seen in the following extract, it stood in a very prominent position. Much of the area was still undeveloped, however it stood in the centre of the junction of a major road to the north, east to the City and west to Westminster. Again so that Eleanor’s memory would be kept in the public memory for many centuries to come.

Following the restoration of Charles II, one of the Regicides (those who had signed the death warrant of Charles I), was executed on the site of the Eleanor Cross. This was Colonel Thomas Harrison who was hung, drawn and quartered on the site of the cross.

A closer view of the statue of Charles I where the Eleanor Cross once stood:

Just behind the statue is a plaque set into the ground which records that the site of the statue was the site of the Eleanor Cross.

The plaque also states that mileages from London are traditionally measured from the site of the original Eleanor Cross, so another example of how the influence of Eleanor’s death can be found today.

As well as adding the word “Cross” to the original village name of “Charing”, Eleanor’s influence can also be seen outside the station of Charing Cross where a Victorian reproduction cross stands in front of the old station hotel:

This reproduction Eleanor Cross was designed by Edward Barry and finished in 1865.

Edward Barry was building on a mid 19th century trend for crosses based on the surviving Eleanor Crosses. This trend was started by the architect George Gilbert Scott. He was working in Northampton in the 1830s and therefore may well have seen the Hardingstone cross.

He would go on to design a number of similar crosses, including the Martyrs Memorial in Oxford, which looks very much like an Eleanor Cross.

Charing Cross:

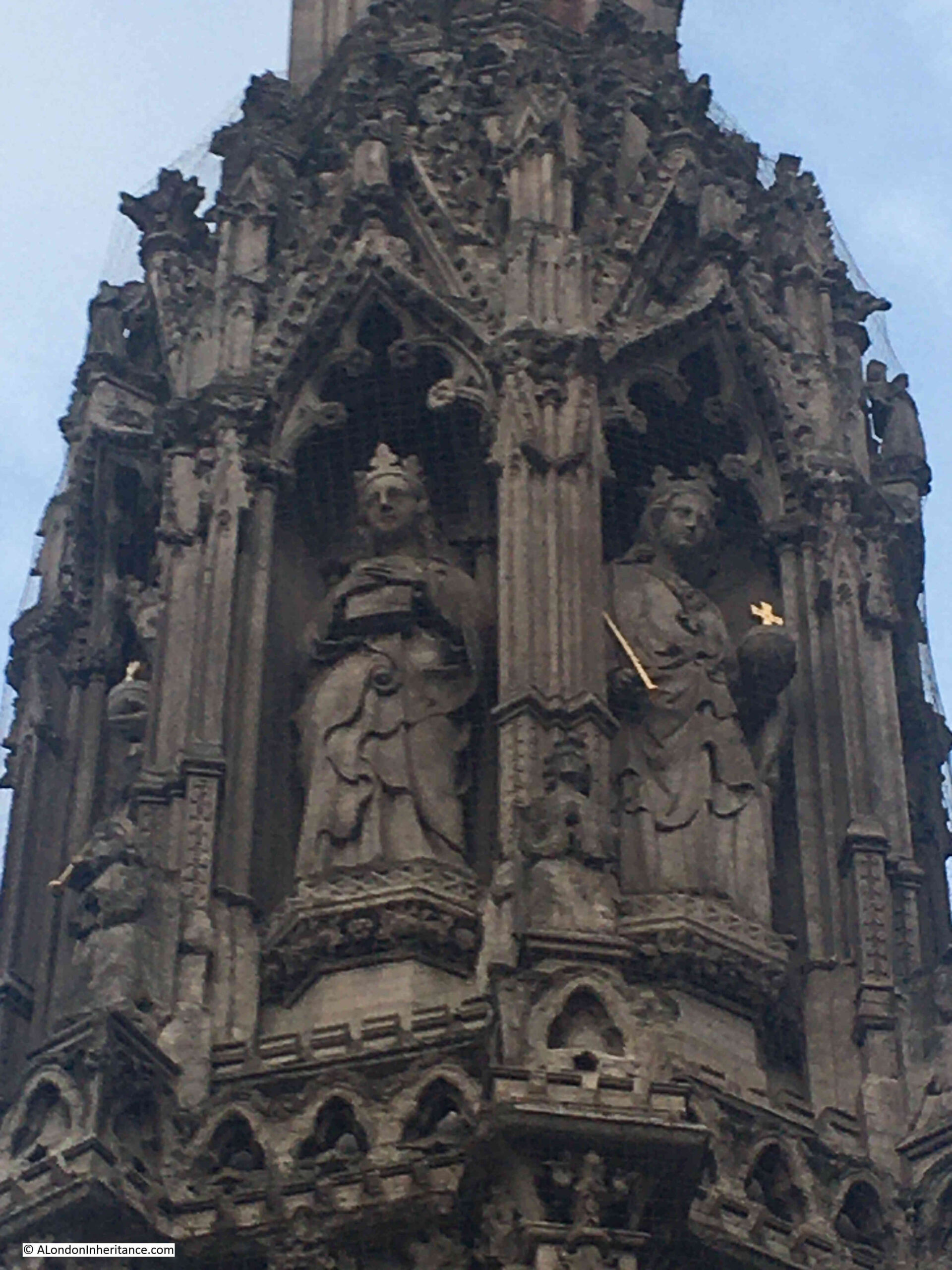

The lower part of the cross displays the arms of England, Ponthieu and of Eleanor of Castile. Above are statues of Eleanor looking out from the cross:

Reminders of the Eleanor Cross extend below as well as above ground at Charing Cross. If you use the Northern Line at the station, you will be greeted by murals running the length of the station platform:

These were created in 1979 by David Gentleman. He researched in detail how a mason would have built the crosses, and the murals run the length of the platform telling the story of the crosses from quarrying the stone, through to completion:

The man on the left is holding a pair of dividers which were used for measurement. In the middle, a stone mason is working on a statue of Eleanor:

Pulling a statue of Eleanor towards a cross, not sure what the two people are doing who appear to be fighting:

A statue of Eleanor arrives at the cross, ready to be installed:

Passing the future location of the cross at Charing, the procession with Eleanor’s body continued on to Westminster Abbey where it stayed overnight.

The funeral was held on Sunday the 17th of December 1290. The service was conducted by the Benedictine monks of the abbey, and Eleanor was buried in a temporary coffin in the abbey as with the suddenness and early age of her death, a fitting tomb for a Queen of England had not yet been prepared.

Westminster Abbey, much modified since Eleanor’s funeral in 1290:

The history of Westminster Abbey deserves several blogs, so for today’s post, the main aim of my visit is to find Eleanor’s tomb rather than explore the history of the abbey.

The interior of the abbey:

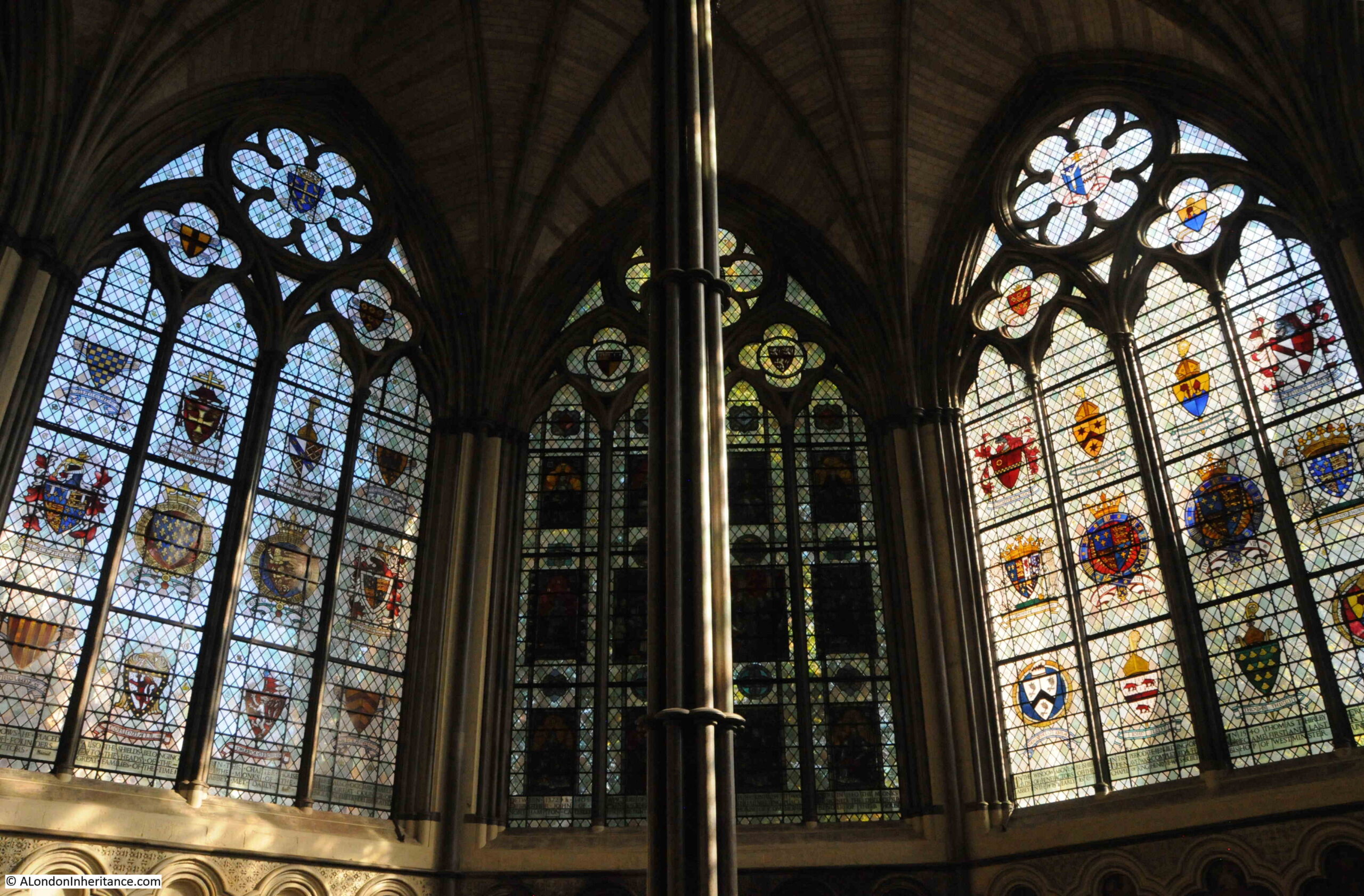

Stained glass:

Eleanor’s tomb was built in the chapel of St Edward the Confessor at Westminster Abbey. I contacted the abbey to see if it was possible to take a photo of the tomb with the bronze effigy of Eleanor, however they do not allow photography within the chapel as it is the spiritual heart of the abbey.

You can see the tomb from outside the chapel, as the tombs in the chapel are arranged around the edge, so after following the route of Eleanor’s body from the small village of Harby where she died, through all the towns and villages where Edward I ordered a cross to be built in memory of Eleanor, I finally stood alongside the tomb where her body was placed:

The tomb was built by Richard Crundale, who was also responsible for the Eleanor Cross at Charing. On the top of the tomb, the gilt bronze effigy of Eleanor, cast by goldsmith William Torel in 1291, is just visible.

On the side of the tomb are the arms which have also been found all along the journey from Harby. The arms of England, of Ponthieu (Eleanor’s mother and which Eleanor also inherited) and of Eleanor of Castile.

Nearby is the tomb of Eleanor’s husband, Edward I, who died almost 17 years later in July 1307:

There is so much to discover at Westminster Abbey, but for now, a couple of highlights, including a door that is believed to date from 1050, so would have been from the time of Edward the Confessor:

The interior of the Chapter House, believed to have been built by Edward’s father, Henry III:

Decorated seating for the monks around the outer wall of the Chapter House:

The floor of the Chapter House is one of the finest medieval tile pavements in England, and contains the arms of Edward’s father, Henry III:

Eleanor and Edward could well have walked on this tiled floor.

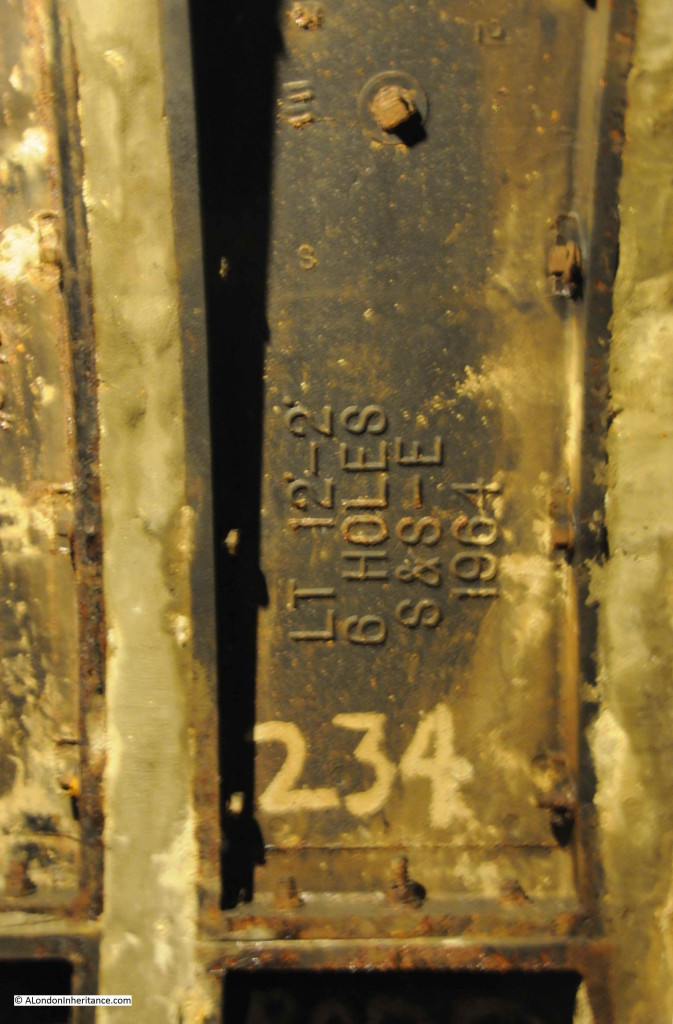

Nearby is the Pyx Chamber, one of the oldest parts of the abbey, dating from around 1070:

The funeral of Eleanor at Westminster Abbey was not however the final act in the long funeral of Eleanor of Castile, there was one last act for Edward I to attend to, and that was the burial of Eleanor’s heart at the Dominican Priory at Blackfriars on Tuesday the 19th of December, 1290.

The priory at Blackfriars was well known to Edward and Eleanor as they had refounded the friary in the 1270s. The heart of their son Alfonso who had died in 1284 at the age of 10 had already been buried at Blackfriars, so Eleanor probably had been planning for her heart to be buried with that of her son.

Apart from the name, there is not much left of Blackfriars today. I did visit a place where the ceremony during the burial of her heart may have taken place, in a previous post on Carter Lane.

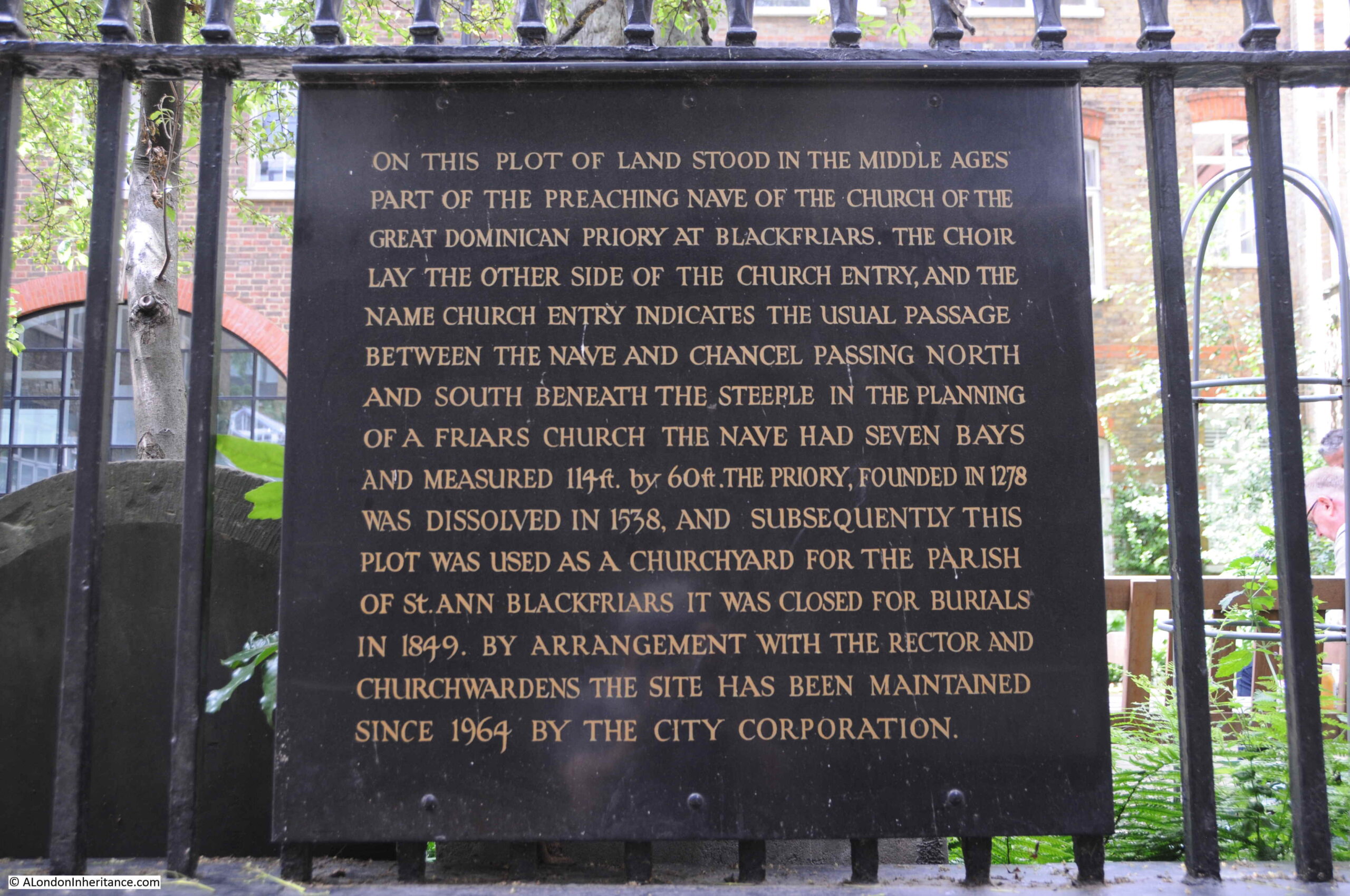

An alley by the name of Church Entry turns off from Carter Lane:

There is a small garden on the western side of the alley:

With a plaque that states that this plot of land is where the preaching nave of the church of the Great Dominican Priory of Blackfriars once stood, so standing in the garden you are in the general area of where the last acts in the funeral of Eleanor of Castile played out in 1290.

Standing at Blackfriars marked the end of my journey from the village of Harby, all the way to London. A fascinating story of a fascinating woman.

There are two main books I have read to research the life of Eleanor of Castile. The first is Eleanor of Castile – The Shadow Queen by Sara Cockerill:

Eleanor of Castile – the Shadow Queen is a thoroughly researched and comprehensive book on the life of Eleanor, highly recommended.

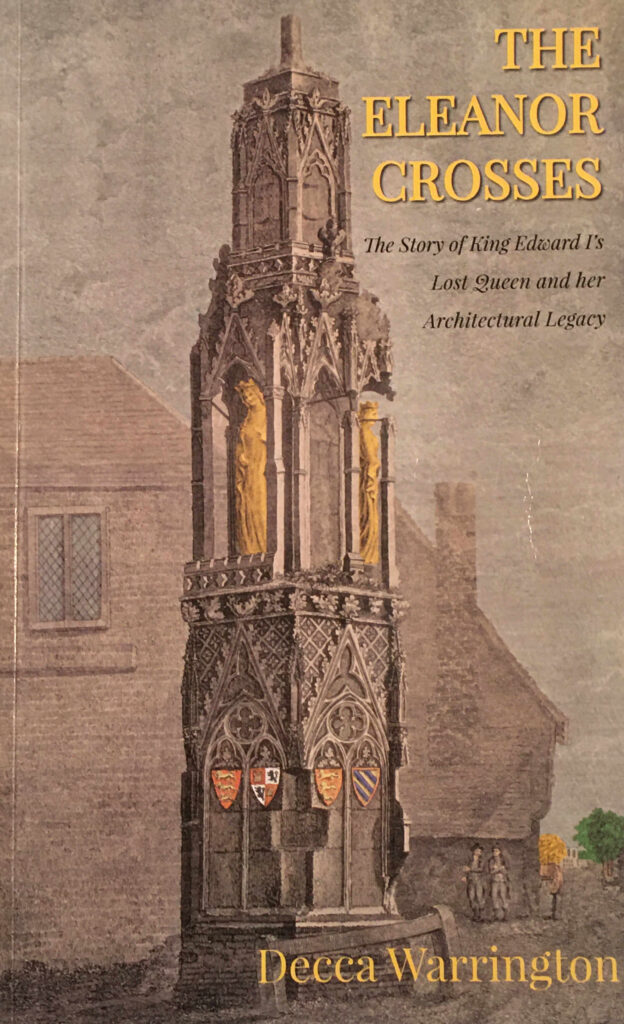

Another book is The Eleanor Crosses by Decca Warrington:

This book is more focused on the life of the crosses, but also contains sections on the life of Eleanor. Recommended as a shorter introduction to Eleanor and the story of the crosses.

For Edward I, the book “A Great and Terrible King: Edward I and the Forging of Britain” by Marc Morris is an excellent read, and for a more academic study of Edward I, the book “Edward I” by Michael Prestwich and published by Yale University Press is an in depth read.

To research the journey and the posts, I also used some of the Victoria County History volumes for the appropriate counties (these can be found online), as well as various publications on the churches and abbeys on the route.

Edward I did remarry after Eleanor’s death. Nine years later in 1299 he married the 20 year old Margaret of France. Edward was 60.

Margaret and Edward had three children (Edward therefore had 19 children in total). The first two were boys. The third was a daughter born on the 4th of May 1306. This daughter was named Eleanor, and whilst this was a common name for women in royal families at the time, she must have been named Eleanor after Edward’s first wife who had died almost 16 years before.

Unfortunately, Eleanor did not live for too long, dying in 1311.

Edward I died in 1307 at the age of 68. Margaret of France was 26 when widowed, but never remarried. Edward I was followed by Eleanor’s eldest son, Edward II, who had a troubled reign, was forced to abdicate, and had a mysterious death in 1327.

Eleanor of Castile was a fascinating woman – one of those from history who would have been brilliant to meet.

Born into a Spanish royal family, highly educated, and with older brothers who were involved in military campaigns when Eleanor was growing up, and whilst her father was reclaiming much of Spain.

Edward was educated, although the English court did not tend to educate their children to the same level as Castile. Much of Edward’s childhood was also spent in Windsor Castle, and he was not so involved with military activity, beyond the basic training needed by a future king.

Edward was though successful when it came to military campaigns. His conquest of Wales led to the building of the string of Welsh castles such as Caernarfon and Harlech castles.

Edward was also brutal in his campaigns in Scotland, focusing brutally on those he thought were disloyal, to such an extent that he acquired the nickname of Hammer of the Scots.

How much of Edward’s success was due to Eleanor would be interesting to discover.

As usual, there is so much I have had to leave out from the format of a blog post (the books mentioned above are well worth a read), but thank you for accompanying me on this journey, alongside Eleanor of Castile.